19

Hustlers

I’ll tell you a story, if I may. Many years ago when I first came to London – I was in the British Museum – naturally. And one of the West Indians who work there struck up a conversation with me, and wanted to know where I was from. And I told him I was from Harlem. But that answer didn’t satisfy him. And I didn’t understand what he meant. I was born in Harlem, I was born in Harlem hospital, I said, I was born in New York. And none of these answers satisfied him and he said, where was your mother born? And I said, she was born in Maryland. And I could see, though I didn’t understand it, that he was growing more and more disgusted with me … more and more impatient. Where was your father born? My father was born in New Orleans. Yes, he said, but man, where were you born? And I began to get it. You know I said, well, I said, my mother was born in Maryland, my father was born in New Orleans, I was born in New York. He said, but before that, where were you born?

James Baldwin (1968)1

‘Where were you born?’ Like ‘Where are you from?’ it was a question which meant different things depending on who asked it, and required different kinds of answer. Asked by one Punjabi-speaker or one Irish person of another it meant which town or village do you call home, and perhaps, where does your family live? It was the opening gambit in a conversation which assumed affinity, and a shared experience of migration. Asked, as in James Baldwin’s story, by a West Indian of an African American it was a question about roots – where did your ancestors come from before they were captured and sold as slaves? The assumption of affinity was much wider; it implied a shared identity between black people across the globe.

‘Where were you born?’ meant something very different in the mouth of a non-immigrant. Asked of a migrant by a native Briton (in a tone ranging from the curious to the suspicious), it was a question about nationality, and ethnicity. But asked of British-born children of black immigrants, with their British accents, it wasn’t a question at all but an accusation and a threat. It was a statement, not about geography but about politics. Ironically it mirrored the pan-black kinship implied by Baldwin’s British Museum attendant, in that it lumped all black people together, wherever they were born. It said to black Britons, you may think you belong but we see it differently – we see difference. As the children of the post-war immigrants became teenagers in the late 1960s the question of immigration had narrowed to a question of colour. And while the children of Irish, Polish, Italian and Cypriot immigrants were identifiable because of their names, the food they ate and where they went on holiday, the children of West Indian, Asian and African immigrants could, apparently, be distinguished on sight.

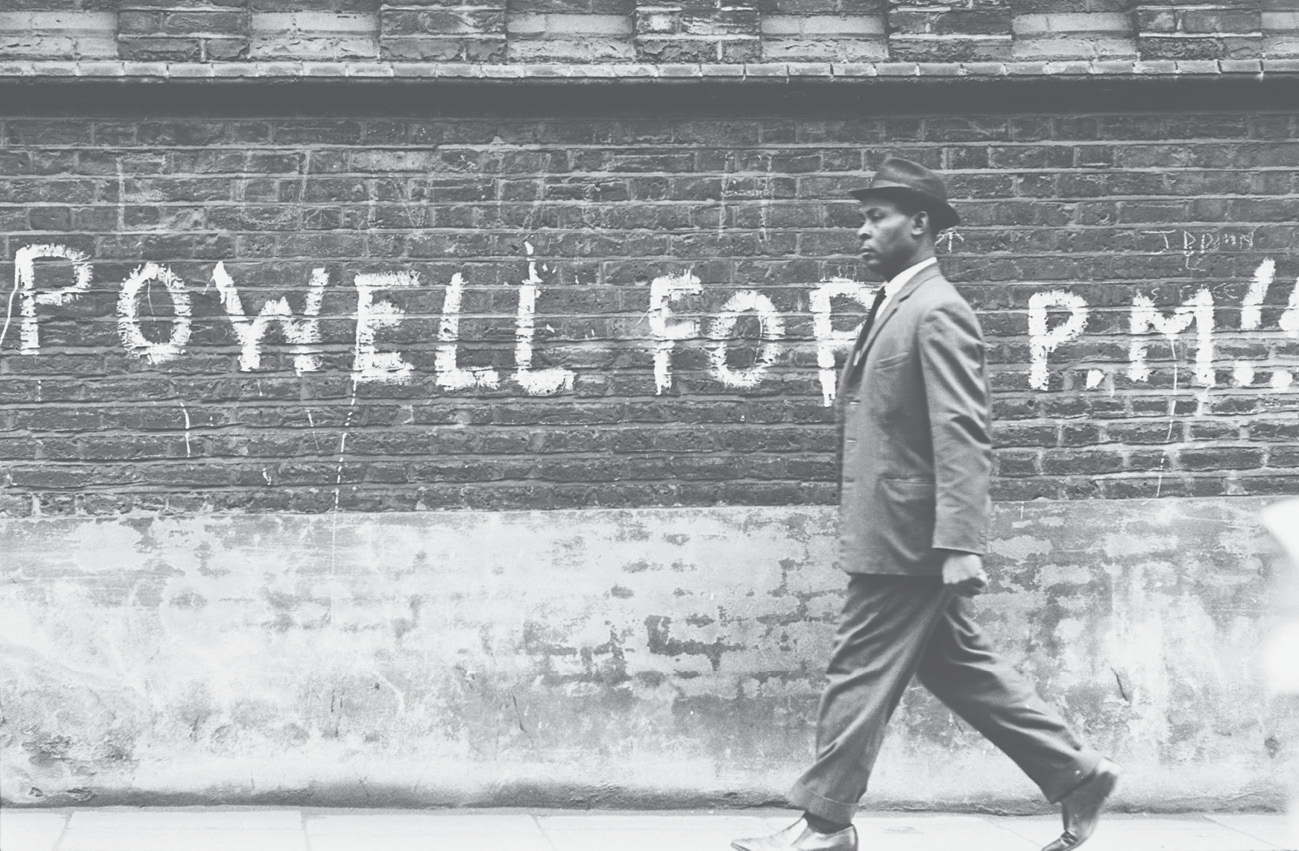

For black and Asian immigrants, and their British-born children, there were two defining TV moments in 1968, which rivalled one another. Both were orchestrated for the public. When Enoch Powell gave his infamous ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech on Saturday, 20 April in Birmingham, it was the culmination of months of agitation and argument against the Labour government’s proposed new Race Relations Bill, which was intended to expand the law to address racial discrimination in housing and employment, areas not covered by the 1965 Act. Powell made sure of maximum publicity for his speech by sending an advance copy to the local television station ATV. The cameras were at the ready to record his broad support for his Wolverhampton constituent (‘a decent, ordinary fellow Englishman’) who feared that the way things were going, ‘In this country in fifteen or twenty years’ time the black man will have the whip hand over the white man.’ Powell argued that the problem was not just one of immigrant numbers, though numbers were part of it. He claimed (erroneously) that the country was welcoming 50,000 Commonwealth dependants every year, ‘who are for the most part the material of the future growth of the immigrant descended population’. It was this ‘native-born’ black population, those who ‘arrived here by exactly the same route as the rest of us’ – i.e. the birth canal – who constituted the real danger in Powell’s eyes. In effect he was arguing that British-born black people could, and would, claim equality with ‘the rest of us’, rather than accept a subordinate role in the life of the country. The numbers meant that ordinary English men ‘found their wives unable to obtain hospital beds in childbirth, their children unable to obtain school places’. But the real problem was immigrant power, the demand for equal treatment. A form of ‘one-way privilege’ was being awarded to the newcomers, who were being granted liberty to complain about the opinions and behaviour of native Britons. Immigrant communities were being given the tools to ‘agitate and campaign against their fellow citizens’. Citizens of the United Kingdom should not be ‘denied [their] right to discriminate in the management of [their] own affairs’; the proposed legislation was a further blow to ordinary English men and women who ‘have found themselves made strangers in their own country’.2

The following days saw Powell interviewed on both BBC and ITN news, and the papers were full of the speech; by Monday the Conservative Party leader, Edward Heath, had sacked him from his Shadow Cabinet and on the Tuesday (the day that the Race Relations Bill got its second reading in the Commons) a thousand East London dockers went on strike and marched to Westminster carrying signs saying ‘Don’t Knock Enoch’, and other, similar slogans. Thousands more joined the strike in the coming days. National polls and letters to the newspapers in the weeks that followed appeared to show a majority in favour of Powell’s stance. Powell himself received over 100,000 letters in April and May, mostly saying thank-you.

The letters were often attributed to multiple signatories – 359 postal workers, for example, or 30 members of a branch bank. They thanked him first of all for speaking up for ordinary workers, echoing the rhetoric associated with Peter Griffiths’ victory in Smethwick four years earlier: ‘at last an honest MP’, ‘the only man who has spoken for us’, ‘a man who puts country before party’. Letter-writers repeatedly insisted they were not ‘racialist’, since they did not believe in the biological inferiority of non-white races. Instead they feared for British culture and traditions which could not survive under the pressure of so many newcomers, who brought with them alien ways of behaving. A surprisingly small proportion of letter-writers focused on the economic consequences of immigration – the strain on social services, or the burden on taxpayers, for example. The overwhelming focus was on cultural rather than economic losses. The boundaries of the nation had long been mapped on to Britishness – and perhaps even more closely on to Englishness – but in the new popular politics of race, the problem of those who could not or would not share that culture had been irredeemably racialized. Immigrants no longer meant all immigrants but ‘Jamaicans, Indians, and God knows what other coloured people’. ‘As an Englishman,’ wrote one citizen to Powell, ‘I would like to think that my son and grandchildren will also be Englishmen, and what’s more look like English men and women.’3

Heath removed Powell from the Shadow Cabinet because he had spoken without the prior approval of the government, and because, as he explained to Robin Day on the BBC’s Panorama programme, his words were ‘inflammatory and liable to damage race relations’. Several newspapers, including The Times, recorded a spike in attacks on immigrants in the immediate aftermath of the speech. A BBC opinion poll in October 1968 found that 8 per cent of immigrants felt they had suffered more discrimination since Powell’s speech. And given the weakness of the 1965 legislation against racial discrimination, there was very little they could do about it. Organizations such as the Campaign Against Racial Discrimination (CARD), a broad umbrella group which was founded in 1965 in order to lobby for stronger legislation, had long argued that the 1965 Act was as good as useless. The Act criminalized discrimination on grounds of race, colour, ethnicity or national origin ‘in places of public resort’, such as hotels, restaurants, pubs, theatres and dancehalls. But it was still perfectly legal to post an ad for a job or a flat stating ‘No Coloureds’ – and there was no attempt to deal with the possibility of racism in public bodies such as the police force, or the criminal justice or education system.

One of the provisions of the 1965 Act was to set up the Race Relations Board to investigate complaints and offer mediation. In practice, most of the complaints were about being refused service in pubs and, as the Campaign Against Racial Discrimination pointed out, the ‘public resort’ clause actually set the bar rather high for grievances. In effect people had to feel strongly enough about the way they were treated to publicize their own humiliation. Discrimination was understood as a matter of personal attitude – whether the person was doing the discriminating or being discriminated against. The Act implied that racism could be dealt with by curbing the behaviour of racist individuals, teaching people guilty of prejudice or intolerance to do better. And it put the onus on individual victims to prove they had been hurt by that prejudice. When the policy think-tank Political and Economic Planning’s Report on Racial Discrimination was published in 1967 it became much harder to ignore the systemic nature of discrimination. The Report detailed multiple examples of black and Asian immigrants being treated as ‘second-class citizens’. These were instances in which immigrants themselves drew attention to unequal treatment, but given the reluctance of many migrants to come forward at all, CARD tried to recruit concerned citizens to gather more evidence. Their leaflet, ‘How to Expose Discrimination’, explained that the real problem with discrimination was that most people didn’t think there was much of a problem, so that it was up to enlightened folk to prove it. There were guidelines for testing landladies and employers, including ‘The Telephone Test’ (get a person with an accent and one without to ring up for the same flat), ‘The Letter Test’ (get two people with the same qualifications, one obviously ‘coloured’, to apply for the same job), and other tests which required rather more effort:

Get two members to apply for estate agents’ lists, specifying exactly the same requirements of size, price, etc., and compare the lists to see that they are the same. Get coloured house-buyers or flat-hunters deliberately to apply for accommodation in previously all-white areas, or better still for housing which they know is up for sale or rent in such areas.

CARD’s aim was to prove that discrimination was widespread, and not just an annoyance for individuals but a cause of systemic disadvantage that required intervention. It was this slow shift in understanding – towards an acceptance that black immigrants were equal citizens, rather than ‘dark strangers’ who had to be more or less tolerated but who could be kept in their place – to which Powell and his supporters were responding.4

The novelist Hanif Kureishi was a teenager in the late 1960s. His father had left Bombay in 1947 to study in London, where he had met and married an English woman. His father’s family had moved from Bombay to Karachi after Partition, where they had become Pakistani. The teenage Kureishi watched his friends on the outskirts of South London become new versions of themselves too – decked out in Union Jack braces, Doc Marten boots and skinhead haircuts, they took to hunting down black and Asian immigrants and beating them:

As Powell’s speeches appeared in the papers, graffiti in support of him appeared in the London streets. Racists gained confidence. People insulted me in the street. Someone in a café refused to eat at the same table with me. The parents of a girl I was in love with told her she’d get a bad reputation by going out with darkies. Parents of my friends, both lower-middle-class and working class, often told me they were Powell supporters. Sometimes I heard them talking, heatedly, violently, about race, about ‘the Pakis’.

Kureishi retreated from his former friends, finding refuge in reading about black liberation movements in the United States: articles on the Black Panthers, novels by James Baldwin and Richard Wright, statements by Muhammad Ali. And he recalls a TV spectacle which rivalled Powell’s speech for its ability to set, or at least announce, a new agenda: the Black Power salute given by members of the US Olympic team in Mexico in October.

A great moment occurred when I was in a sweet shop. I saw through to a TV in the backroom on which was showing the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico. Thommie [sic] Smith and John Carlos were raising their fists on the victory rostrum, giving the Black Power salute as the ‘Star Spangled Banner’ played. The white shopkeeper was outraged. He said to me: they shouldn’t mix politics and sport.5

The Pakistani-born writer Dilip Hiro also understood the event as signalling a radically new understanding of what it meant to be black. Seeing black Americans invoking Black Power on the television, ‘millions of black people in the Western World instantly identified with them’, not only those of African heritage. Arguably the pan-black alliance that began to gain ground in Britain in the late 1960s was simply echoing the logic of those who argued that black immigrants were the problem, wherever they came from (‘Jamaicans, Indians, and God knows what other coloured people’). After all, Powell had specifically targeted ‘Negroes’, immigrant children who apparently knew no English except the word ‘racialist’ (‘They cannot speak English, but one word they know …’) and the Sikh community, which was campaigning in Powell’s Wolverhampton constituency for transport workers to be allowed to wear turbans at work. Government officials and white supremacists alike began to use the term ‘Afro-Asian’ to refer not to people of mixed race but New Commonwealth immigrants in general.6

Comparisons with racial politics in the United States had come full circle since the 1958 riots in Notting Hill. Back then the possibility that London (or Nottingham) might have anything in common with Little Rock, Arkansas, was raised only in order to be dismissed. The Commonwealth of Nations had been built on the principles of equal citizenship and tolerance, and Britons liked to congratulate themselves (implausibly) on not being defined by a history of slavery. Ten years later it was precisely fears of ending up like America that fuelled overt anti-immigration rhetoric, including Powell’s doom-laden threat that Britain would inevitably fall to rioting and racial unrest: ‘that tragic and intractable phenomenon which we watch with horror unfolding on the other side of the Atlantic’. In the summer of 1967, riots and civil disturbances by mainly black protestors caused looting, destruction and the deaths of twenty-six people in Newark, New Jersey, and of forty-three people in Detroit. In early April 1968, following the assassination of Martin Luther King, there were riots across more than a hundred American cities, including Chicago, Baltimore and Washington, DC, in which thirty-nine people (thirty-four of them black) were killed. The concern of Powell’s ‘decent, ordinary, fellow Englishman’ that the black man would soon have ‘the whip hand’ over the white acknowledged both that the racial histories of the United States and Great Britain were not so different after all, and that black people appeared unwilling to put up with their allotted role.

The official line was that Britain’s racial problems were entirely different from those of its former colony. The Times, for example, insisted that,

Nothing could do more harm than if the present troubles in America are taken to be an accurate, if enlarged, account of the problem we face here. Almost all the stereotyped images based on the American situation are utterly misleading when applied to Britain. For Birmingham, Alabama and Birmingham, England are, in the end, quite different.

Indeed part of the attraction of America’s revolutionaries to young black Britons was that they behaved so differently from their parents’ generation in England. When Hanif Kureishi tore down the posters of the Rolling Stones and Cream from his Bromley bedroom wall, and replaced them with pictures of the Black Panther leaders – Eldridge Cleaver, Huey Newton and Bobby Seale, sporting Jimi Hendrix haircuts and holding guns – he did so because ‘[t]hese people were proud and they were fighting. To my knowledge, no one in England was fighting.’ But Powell’s supporters convinced themselves that they soon would be.

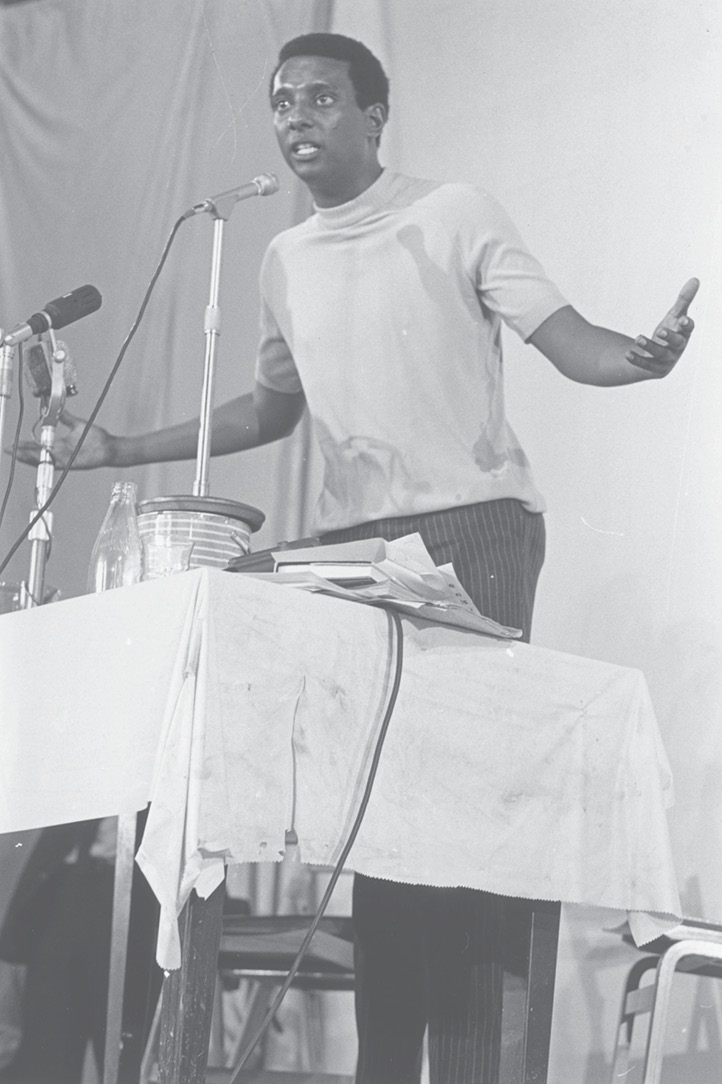

It was obviously unreasonable to argue that Sikh bus drivers who wanted to be able to wear turbans at work were plotting the overthrow of white civilization. But American black revolutionaries had been giving speeches and making contacts in Britain which the government deemed dangerous to race relations. Soon after the 1965 visit by Malcolm X to Smethwick, Michael Abdul Malik (formerly Michael de Freitas/Michael X), along with Guyanese immigrant Roy Sawh, had founded the Racial Adjustment Action Society (RAAS) to agitate for racial equality. Bringing together Marxism, revolutionary nationalism and West Indian activism, RAAS was described in the Observer as an ‘openly militant’ group, ‘born in the slums of London’s Cable Street and Powis Square’. The 1966 publication by the West Indian Standing Conference of J. A. Hunte’s investigation into police brutality, Nigger Hunting in England?, and of Neville Maxwell’s The Power of Negro Action in 1965 seemed proof that tension was mounting. The rhetoric of Black Power – the insistence on the necessity for militant black defence against white aggression – was migrating to Britain. And in the summer of 1967, while Detroit rioted, Stokely Carmichael, former chairman of the civil rights group the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and an advocate of Black Power, made a ten-day visit to London, which was widely covered by the BBC, ITV and national papers.7

Carmichael was invited to address the Dialectics of Liberation Congress, held in July in Camden’s Roundhouse. The acme of 1960s counter-cultural debate, the Congress was flagged as ‘a unique gathering to demystify human violence in all its forms, the social systems from which it emanates, and to explore new forms of action’. For two weeks the proponents of radical anti-psychiatry, such as R. D. Laing, took the floor alongside Beat-generation writers (Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs), philosophers such as Herbert Marcuse, and the proponents of various strands of revolutionary racial action: C. L. R. James, Michael Abdul Malik, Obi Egbuna and Roy Sawh. It was an entirely male line-up, as were most of the revolutionary reference points: Che Guevara, Chairman Mao, Frantz Fanon. A twenty-four-year-old civil rights activist from Derry, Eamonn McCann, spoke on discrimination against the Catholic population in Northern Ireland. He was of the highly politicized, liberal, younger generation of Irish immigrants in Britain who were rejecting wholesale what they regarded as the quietist conservatism of the post-war generation. They scorned those Irish who poured their energies into the British Labour Party at best, and at worst the emigrant County Associations (‘dominated by people who craved acceptance and middle-class respectability’) and the Catholic Church.8

The Irish radicals took their cue – and much of their language – from the American civil rights movement and, just as in the United States, there were fierce battles over whether it was better to take a reformist or revolutionary route to political change. Fionnbarra Ó Dochartaigh, who would later take a leading role in the Derry Housing Action Committee and the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association, was, until he returned to Derry in 1966, a member of the London-based socialist and republican Connolly Association, which insisted on the parallel between the emancipation of the American South and of Catholics in Northern Ireland. But by the mid-1960s there were several alternative forums for politically minded Irish immigrants. In 1964 the Irish republican movement set up Clann na hÉireann as a support, fund-raising, and recruiting organization for the IRA in Britain – principally in Birmingham and Glasgow. The Clann ran ceilidhs and old-time dances, and started a ‘Buy Irish’ campaign to deepen their roots in the Irish community in Britain. One young organizer, Pádraig Yeates (the Birmingham-born son of Irish emigrants), advocated a campaign focused on aiding Irish immigrants, and publicizing discrimination against them. But the Clann also recruited volunteers who travelled to Wexford or Wicklow for military training (nicely convenient to the ferry). There was even a short-lived alliance with the Free Wales Army, which involved a cache of gelignite filched from mines in South Wales that eventually ended up dumped in a canal somewhere between Glasgow and Salford. But young Irish immigrants such as Eamonn McCann – one of the organizers of the historic civil rights march in Derry in October 1968 – were drawn to more intellectual leftist organizations, such as the Irish Communist Group and the Irish Workers’ Group. Speaking in Stormont, the Northern Ireland Parliament, in 1968 William Craig, the Ulster Unionist politician who banned the Derry march, laid part of the blame for the revolutionary civil rights demands at the door of London-based radicals:

Of the other elements involved perhaps it is worth mentioning the Irish Workers Group, which is a revolutionary Socialist group which aims to mobilise the Irish section of the international working class to overthrow the existing Irish bourgeois states, destroy all remaining imperialist organs of political and economic control and establish an all-Ireland Socialist Workers Republic. The leader is Gerard Richard Lawless of 22 Duncan Street, London, a former member of the I.R.A. who was interned by the Government of the Irish Republic in 1957. Eamon McCann of 10 Gaston Square, Londonderry, a prominent participant in the unlawful procession, is chairman of the Irish Workers Group in Northern Ireland.9

Lawless was also a member of the IMG (International Marxist Group), along with Tariq Ali. In these meetings the debates focused on the ideas and dilemmas of the New Left: anti-imperialism, decolonization, nuclear disarmament, and the movement against the Vietnam War.

This was the context of the Dialectics of Liberation Congress, and in Stokely Carmichael’s mouth its language was uncompromisingly combative. Taunting a speaker from the floor for failing to curb white power (‘You haven’t done a goddam thing to stop white violence, have you? Have you?’), he insisted on the right of black communities to use violence: ‘It’s my survival I’m fighting for, white boy.’ There would be no change in the status quo until the ‘white man’ learns that ‘he can die just like anybody else’. When Carmichael left London for North Vietnam the home secretary, Roy Jenkins, banned him from entering the country again as his presence was ‘not conducive to the public good’. Michael Abdul Malik was deputized to give an upcoming speech in Reading in his stead. The speech, which called for the death of any white man seen ‘laying hands’ on a black woman, was recorded by a Daily Express journalist and quoted by Conservative MP Duncan Sandys in the Commons, with a call for Malik to be prosecuted under the 1965 Race Relations Act. ‘I am quite satisfied,’ said the judge in the September 1967 trial, ‘you came down here to this peaceful town in order to make trouble, which is just what the Act is meant to avoid.’ He was sentenced to a year in prison for ‘intent to stir up hatred against a section of the public in Great Britain, distinguished by colour’.10

Just at the point that the laws against racial discrimination were expanded and toughened, it appeared to many people they could never be enough. Indeed some argued that the legislation was designed all along to suppress black radicalism rather than white racism, and Malik’s arrest and prosecution appeared to prove it. But even if the legislators were given the benefit of the doubt, the problems of racial discrimination went far deeper than the ‘everyday’ prejudices the law was intended to tackle. The whole idea of ‘Race Relations’ assumed a goal of integration, but the watchwords of the radical groups who were seeding themselves in Oakland, Chicago, Paris, London, Belfast and Derry were not integration, and not even civil rights, but international socialism, revolution and liberation. ‘Integration is not our aim, it’s our problem,’ James Baldwin insisted at a meeting in the West Indian Students Centre in February 1968. The price of integration was assimilation, the disappearance of what was distinctive about black cultures.

For radically minded immigrants, the task was to shift the focus away from individual racial slurs and towards social and economic marginalization, the systematic disadvantage black people suffered at the hands of employers, local councils, financial institutions (insurers and mortgage companies), the police and the criminal justice system. The Black Regional Action Movement, for example, operating out of 108 Mercers Road in Tufnell Park, London, produced a roughly printed magazine called Black Ram through the latter half of 1968 and early 1969. The articles focused on housing, the need for black history to be taught in schools, the 1968 Guyana elections, and the case for a nationwide black strike. The first issue of the – ironically titled – magazine Hustler was produced at number 70 Ledbury Road in Notting Hill in May 1968, and alongside the main article on Powell (‘Who Knocks Enoch’), most of the pages of this first issue were devoted to the still dire local housing situation. The magazine saw itself as a local campaigning journal, and included articles explaining to local residents ‘How to use the Rent Act’ against unscrupulous landlords, and keeping them up-to-date with the redevelopment of the area around Lancaster Road. The second issue included a piece on ‘Your Rights’ by white lawyer and local councillor Bruce Douglas-Mann, who would be elected Labour MP for Kensington North in 1970. He pointed out that according to the 1967 local housing survey, black residents were still getting a raw deal:

They show that the average rent paid by West Indians and Africans for one-room and three-room lettings is 30 per cent higher than the average rent paid by English, Irish and Europeans; in two-room flats, rents paid by coloured immigrants are, on the average, 60 per cent higher than those paid by white people in the area.

Moreover, 75 per cent of ‘coloured immigrants’ were in furnished accommodation – which was not only more expensive but provided fewer rights in terms of rehousing – compared to 25 per cent of white people. There had been no significant improvement in conditions since the Milner Holland Report three years earlier (and nothing had changed when Notting Hill housing was discussed in the Commons the following year). But this issue of Hustler also carried an article describing recent attacks on immigrants in Wolverhampton by white people shouting their support for Powell. And over the following months, alongside star signs, African fashions and the latest soul releases, more and more space was devoted to international black revolutionary activism: articles on the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa, and on black theatre in Harlem, Andrew Salkey on ‘Revolution and the Artist’ in Cuba, a piece by ‘black art’ poet LeRoi Jones (later known as Amiri Baraka) on Black Power in his home town of Newark after the riots, and an account of the political journey of ‘Black Power Michael’.11

Hustler’s mix of culture and politics, and its underground-press style – the layout, though black and white, mirrored that of alternative pop-art magazines such as the International Times and Oz – placed it at the interface between London hippie culture and local black activism. The calls to resist rent rises, to open the garden squares to local people and to start a revolution in North Kensington echoed the rhetoric of the London Free School, which had been set up by a broad coalition of counter-cultural artists (Pink Floyd played All Saints Church Hall in Talbot Road in October 1966) and community action projects, ranging from a playschool (Michael Abdul Malik got Muhammad Ali to visit the school in Tavistock Crescent), classes in African history, rent and housing support groups, and an adventure playground on the site cleared for the construction of the Westway. Malik had his finger in most of these pies, and arguably had effected the transition from Rachmanesque rack-renter to bohemian Robin Hood with remarkable aplomb, though there were concerns that his previous reputation could not be so easily dismissed, and some local residents kept away from the London Free School because of it. And part of the reason the London Free School could operate in the area at all, occupying abandoned and condemned buildings, was because so little had been achieved in terms of improving the housing situation for the majority of residents.

The August 1968 issue of Hustler advertised a weekend ‘Seminar on the Realities of Black Power’ to be held at the West Indian Students Centre, printed a Black Power statement from the United Coloured People’s Association, and covered the arrests of Obi Egbuna, Peter Martin and Gideon Dolo for the racial content of speeches they had given in Hyde Park. They were accused of inciting violence against police officers. Roy Sawh was charged under the same legislation for calling for ‘coloured nurses to give wrong injections to patients, coloured bus crews not to take the fare of black people’ and Indian restaurant owners to ‘put something in the curry’. By January 1969 the entire magazine was devoted to Black Power. Alongside pieces on Mozambique and Vietnam, the focus was on the recent meeting of the Black Peoples’ Alliance, composed of West Indian, Indian, Pakistani and African organizations and individuals, which had produced a manifesto calling for ‘a militant front for black consciousness and against racialism’, and repeal of the 1962 Commonwealth Immigrants Act. This was Black Power filtered through the perspective of immigrants to Britain.

Obi Egbuna was a thirty-year-old Nigerian law student who had published a novel in 1964, and had his first play, The Anthill, produced the following year. As a member of the Committee of African Organizations, he had helped organize Malcolm X’s visit to England in 1965; in 1966 he spent several weeks with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee campaigning in the United States. In September 1967 he co-founded the United Coloured People’s Association, and published a manifesto, Black Power in Britain, which closely mirrored arguments which had been made by Carmichael at the Roundhouse in July. Black people were not the ‘initiators of violence. But if a white man lays his hand on one of us we will regard it as an open declaration of war on all of us.’ Six months later he started the British Black Panther Movement, a revolutionary socialist group explicitly modelled on the US Panthers, and began editing its journal (there were three issues before his arrest), Black Power Speaks. The British Black Panthers were just one of a number of groups that began promoting the idea of a black working-class revolution, and which opened up the fissures between the goals of integration and liberation for black immigrants. Ambalavaner Sivanandan, then the librarian at the Institute of Race Relations in London (and who would later, as its director, take the organization on a more radical, anti-integrationist path), recalled that, ‘Black Power, in particular, spoke to me very directly because it was about race and class both at once. More than that, it was about the politics of existence.’12

Given the violent rhetoric of many of these speeches and publications, and the explicit echoes of the aims of the American Black Panthers, it should come as no surprise that men such as Michael Abdul Malik and Egbuna were attacked in the press and in Parliament. It seemed obvious that Black Power meant disorder and social unrest, and what’s more it was alien to Britain, because British culture was (flying in the face of history) not marred by a slave-owning past – or at least not one which had played out on British soil. When Malik referred to the West Indies as England’s ‘deep south’, suggesting similarities between the experience of African Americans and of West Indians, he was condemned in the press for making inflammatory and hysterical remarks. Colin MacInnes, in the New Statesman, argued for caution in rejecting the analogy. Britain had created her ‘deep south’ overseas, and just as southern African Americans had moved to the industrial North, so West Indians had moved to the Mother Country, where they were treated with much the same disdain as black people in America. MacInnes asked the readers of the New Statesman to imagine themselves in their place: ‘let us make the imaginative effort to see Britain as does an intelligent, if not necessarily literate or affluent, black immigrant to our country’.13

We get some sense of that particular black immigrant perspective from a remarkable film made in February 1968 by Horace Ové, of a meeting in the West Indian Students Centre addressed by the American novelist James Baldwin on the subject of revolutionary politics. It was the second film shot by Ové, who was not yet thirty, and who had moved to Britain in 1960 from Belmont, Trinidad (where Michael X/Abdul Malik was from), to study art. He would go on to direct Pressure in 1976, the first black British feature film, about the effect of police brutality on young black men, and the increasing gap in understanding and attitudes between the first generation of West Indian immigrants and their children. Ové was typical of one section of Baldwin’s London audience that day – the camera shows a number of young, polo-neck-jumper-and-corduroy-jacket-wearing students, writers and artists. Andrew Salkey is there, sitting prominently at the front. But there are also people who, from their questions, are clearly working men and woman, as well as a few white and Asian faces in the crowd. Why does Baldwin use the word ‘negro’, one asks, rather than ‘black’? Why has he written contemptuously of an African past? ‘Which is better, integration or Black Power?’ In fact that was a question which had been posed by ITN’s This Week in a programme which had aired a few weeks before, in January 1968. On this occasion it was posed by a Jamaican woman who was concerned that Baldwin should appreciate the difference between being a West Indian in Britain, and being black in America:

Now that I am in England, I am very glad that I came to England because I am more aware of the fact I’m a negro. In Jamaica I wasn’t aware of the fact, because it’s very cosmopolitan. And in Jamaica, I don’t know if you’ve ever been told, we have more of a shade problem … I never knew I was a real negro until I came to England. I know now.14

Baldwin’s own comments that day focused on black internationalism. In Saigon, in Detroit and South Africa, ‘the same war is being waged’. ‘Thinking black’ meant rejecting the chains of slavery, and for him the ‘whip hand’ was not just a metaphor. Slavery was the point of Baldwin’s account of his conversation with a West Indian British Museum attendant when he first visited London (‘where were you born before that?’). For, as he explained, he did not and could not know about his family history prior to the arrival in the United States. His ancestors were subject to a bill of sale which erased all information about origin, and which did so deliberately to disempower the men and women who from then on were forced to act ‘under the whip’; ‘we know who had the whip’. Slavery had robbed black people of their history and culture, and for Baldwin it was this fundamental rupture which necessitated a rediscovery of Black Power. Nonetheless, there is something puzzling in the story Baldwin told that day, for it was most unlikely that the British Museum attendant who struck up a conversation with him knew for certain where he himself was born ‘before’ he was born in Jamaica or Trinidad or Barbados. His ancestors too would have been subject to a bill of sale, which wiped out the past. What, then, was really at stake in his question to Baldwin? That as a West Indian he had a ‘past’ identity that he had brought with him to Britain, and that he assumed Baldwin must also have had in relation to the United States? That Baldwin must (because he was black) feel like an immigrant and hold on to a past from elsewhere?

Like the woman who explained the ‘shade problem’ back in Jamaica (she could barely make herself heard over the laughter of recognition), the British Museum attendant was voicing the particular character of experience for Britain’s New Commonwealth population: that they were black, but they were also immigrants. Even if the West Indies (or indeed the Punjab, Mirpur and Sylhet) could be understood as Britain’s deep south, they no longer lived there. At least part of their identity was bound up with where they had come from. At least part of their alienation had to be understood in geographical, rather than racial terms. It was this that made the principal difference between the first generation of migrants and their children. There were plenty of men among the first wave of immigrants who turned towards radical politics. Obi Egbuna and Michael Abdul Malik were obvious examples, but so were those such as Tariq Ali, Stuart Hall, Darcus Howe, Sivanandan, and others who were involved with the anti-Vietnam War movement, the International Marxist Group and the New Left Review in the late 1960s. Enoch Powell’s populist racist politics created a response among black immigrants in Britain which mirrored, and to some extent modelled itself on, the Black Power movement in the United States. The injunction to ‘think black’ was born of a desire to validate West Indian experience in a context where it was being belittled and unrecognized. It was telling that the writers associated with the Caribbean Artists Movement, who had arrived in Britain determined to make their mark on the metropolis, began in the late 1960s to shift their focus towards a specifically black audience. (Andrew Salkey argued, ‘I began by seeking metropolitan approval. We must first seek approval of the fruits of our imagination within our society.’) But ‘thinking black’ also involved mirroring the way immigrants were perceived by their neighbours. In the early 1950s when the first migrants arrived from Jamaica, Trinidad and Guyana, they began to acknowledge a new identity as ‘West Indian’. By the late 1960s, an even more broadly defined identity had taken over. It wasn’t just, as the West Indian woman who spoke to James Baldwin joked, that they had become ‘real negroes’, but they had become black, part of a coalition of colour which, in its struggles with a white coalition, would help redraw the map of British politics in the early 1970s. Nonetheless, even if the new consciousness of radical blackness was available to all New Commonwealth immigrants, it was certainly not availed of by all of them. There were divisions based on class, language, religion and, above all, the division between those who migrated in the post-war years, and the generation that was born in Britain.15

In the mid-1970s the American sociologist Thomas J. Cottle spent two years researching a book of interviews among the ‘poor West Indian families of London’. Along the way he met sixteen-year-old James Coster, who was born in Hammersmith of Jamaican parents, and who would have been ten or eleven years old when Powell gave his speech, and when the American sprinters saluted Black Power in Mexico. A real-life version of one of the young men in Ové’s film Pressure, which was made around the same time, Coster was barely willing to talk to Cottle at all, since he was white, and so talking was pointless. He looked forward to the complete transformation of the political landscape in Britain, and celebrated the revolutionary end of a politics based on promises which were never kept. Because ‘we don’t eat promises, or live in them’. He was eloquent about his wholesale rejection not of his parents, but of his parents’ quietism, their belief in the value of respect, and respectability:

‘My life is devoted to politics,’ he said, ‘but not any politics of the old days. All you have to do is look around and you can see what’s going on. There’s nothing different, or special about England. White man sits very heavy right on top of the black man. He might not think he is, but you talk to any black man and he’ll tell you he is …

‘You in America, you call what I’m saying a separatist movement. Look out, whitey, black people aren’t going to talk to you no more, or listen to all your promises and deals. I don’t like that word, separatist. All we’re doing is reacting to the way white people treat us. If white people exclude us, we can do one of two things. Either we can say all right, we’ll try to get by, we’ll feel bad but we’ll try to get by. Or we can say, before you push us out, we’re going to be on our own, and be strong being on our own. We’re going to show you how we don’t need you, and how someday, when we’re as strong as we’re going to get, you’re going to need us. White people don’t like it when they don’t know for sure what black people are thinking, and doing, and feeling. They don’t like it …

‘Everybody’s going to have to learn a new way of dealing with one another. My father and mother, they still listen to all the promises. Maybe they won’t change, but they can understand why things will have to change …’16