THIS CHAPTER PRESENTS AN OUTLINE of how we are biologically hardwired, and the implications of this learning for working safely with parties in mediation. It outlines the basic functions of each part of the brain and specifically the ways in which parties become stressed in conflict or during mediation.

No area of understanding is more relevant and important to mediation competency than a basic understanding of how the human brain functions, perceives events, processes emotional notions, cognitive response and formulates decisions. The awareness of cognitive neuroscience and psychology are at the heart of our work in managing conflict and problem solving.

— Robert Benjamin15

The theories and concepts in this chapter form the basis of the methodology that needs to be employed for asking questions using the S Questions Model.

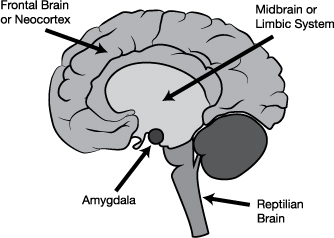

The physician and neuroscientist Paul D. MacLean16 states that the human brain has evolved into three independent, but interconnected, layers of brain matter referred to as the triune brain. These layers of distinct evolution are known as the reptilian brain, the midbrain or limbic system and the frontal brain or neocortex.

This is the most primitive part of the human brain that started to evolve more than five hundred million years ago. It is the location of the instinctive survival reflexes. The reptilian brain regulates functions such as digestion, circulation, breathing and heart rate, any of which can be affected if we feel threatened.

Figure 3.1: The Evolution-formed Triune Brain

CREDIT: O’SULLIVAN SOLUTIONS

This is the second layer of the brain. It contains the amygdala and is believed to be the part of the brain where information from the senses (sight, sound, touch, smell and taste) is first processed. Here is where our emotions are generated as a first reaction to any stimulus from the senses and where our unconscious memories, including our emotional memories, are stored.

The amygdala is our threat detector. It calculates whether a stimulus is to be feared and avoided, or whether something is a reward and can be approached. The amygdala’s evaluation of the stimulus, with reference points to past experiences and memories of perceptions, determines the conscious experience of our feelings. In the past, the presence of a wild animal represented real danger, but today’s threats are less clearly defined, and therefore more complex.

The amygdala processes information from our five senses and from our memory. If no memory of any threatening significance is evoked, then the information travels on to the frontal brain (neocortex).

Conscious memory and high-order cognitive thinking take place in this layer of the brain. It controls higher functions such as language, logic, reasoning and creativity.

When we are highly stressed, the functions of the frontal brain disconnect due to the negative impact of stress hormones on the hippocampus. The hippocampus is a small organ that forms an important part of the limbic system, which regulates emotions. The hippocampus is associated mainly with memory, particularly long-term memory, which includes all past knowledge and experience.

Because stress hormones have a negative effect on the hippocampus, a flood of them leaves us in an emotionally charged state, without input from the cognitive thinking brain. We may start to think and act irrationally, but the extent to which this happens depends on our level of emotional intelligence.

We will now turn to the physiological process that occurs when we have a sudden, strong emotional reaction to a stimulus.

Amygdala hijack18 is the term used to describe a sudden and disproportionate emotional reaction to a stimulus that has evoked a strong emotional memory from our past. A part of the limbic system, the amygdala is the emotional center of the brain and reflects our fundamental needs. It can produce split-second responses when we feel threatened. We experience a sudden and disproportionate emotional reaction to a stimulus when someone else’s values, needs, interests, beliefs, assumptions or perceptions may seem incompatible with ours. This stimulus may evoke a fearful response in us. The more emotionally intelligent and self-aware we are, the easier it is for us to regulate our emotions and access our rational brain during conflict. But if we are unable to do this effectively, we will enter the grip of an amygdala hijack and be unable to access our frontal cognitive thinking brain until we have calmed down.

When an amygdala hijack occurs, this indicates that something that is of fundamental value to a person is perceived by them to be under threat. This emotional response to a stimulus, and the triggering event that caused it, needs to be explored to give parties in mediation an opportunity to talk effectively about their issues and their accompanying emotions.

It is only after this has been done that discussions can move on to exploring options for solution. If a party is asked about possible solutions when they are in the grip of an amygdala hijack (and so in a highly emotional state), they may be unable to give an effective cognitive response.

From a neurological perspective, the role of a mediator may be described as minimizing perceptions of danger enabling cognitive appreciations of emotions, dampening the amygdala and helping parties to self-regulate.

— Jeremy Lack and Francois Bogacz21

David Rock has written many of the central academic and discussion papers that have defined the field of neuroleadership.22 His social neuroscience theory explores the biological foundations of the way people relate to each other and to themselves. Rock states that two themes are emerging from studies of social neuroscience:

• Firstly, that much of what motivates and drives our social behavior is governed by an overarching organizing principle of minimizing threat and maximizing reward.23

• Secondly, that several domains of social experience draw upon the same brain networks used for primary survival needs.

Rock suggests that human beings may be hardwired evolutionarily and may have been created to respond to ten neuro-commandments that encompass the need to minimize threat, maximize reward and have our emotions regulated.

Ten Neuro-commandments

1. Thou shalt avoid pain and seek reward

2. Thou shalt be more sensitive to danger or fear than to reward

3. Thou shalt regulate your emotions

4. Thou shalt operate cognitively in two gears

5. Thy social stimuli shalt be as powerful as thy physical ones

6. Thou shalt seek comfortable status positions

7. Thou shalt always predict to have a sense of certainty

8. Thou shalt retain your autonomy

9. Thou shalt relate to others

10. Thou shalt prefer fair behavior

Rock maintains that neuro-commandments 1 to 5 encompass the need to minimize threat, maximize reward and have our emotions regulated, while neuro-commandments 6 to 10 encompass the SCARF® Drivers: status; certainty; autonomy; relatedness (being connected to and similar and secure with others); and being treated fairly.24

Rock states that these SCARF® Drivers are treated in the brain in much the same way as our primary needs for physical safety, food, water and shelter are. Unfulfilled SCARF® Drivers have the same impact on the brain as a physical threat and may result in an amygdala hijack.

Let us now look at each of the neuro-commandments individually.

Humans are driven to minimize or avoid pain, and to maximize reward. If there is a sense that they are in danger or are afraid, resulting from a negative triggering event, then biological hardwiring, governed by memories of stimuli, will trigger an avoid-threat reflex. If a threat is detected, the sympathetic nervous system is stimulated and prepares to meet that stressful situation, resulting in a fight or flight response, as necessary. If a person senses a reward, they will unconsciously and automatically display an approach-reward reflex.

The avoid-threat reflex is far stronger and longer lasting than the approach-reward reflex. While this is a protective mechanism, it leads to our inability to think cognitively and clearly when we are in a negative emotional state.

When the amygdala is activated, it draws resources of oxygen and glucose from the frontal brain, which is then left without its necessary resources to perform cognitive thinking. It is through conscious awareness and the development of social and emotional intelligence that self-regulation can take place. This then leads to our ability to cognitively assess a social stimulus so that scripted patterns of behavior are overcome.

When parties in conflict are emotional, they react and act on auto-pilot or default mode. This is referred to as the X-system, as proposed by Matthew D. Lieberman25 and quoted by Jeremy Lack and Francois Bogacz in their paper “The Neurophysiology of ADR and Process Design: A New Approach to Conflict Prevention and Resolution?”:26

Human beings have two basic modes of functioning:

• The first is called the “reflexive mode” which is regulated by neural assemblies in the brain known as the “X-system.” This system relies primarily on patterns to make unconscious predictions, and on cognitive reflexes. This is the auto-pilot state of immediate and unconscious reaction that we function in most of the time.

• The second mode is called the “reflective mode,” and it is the responding mode that is regulated by a different neural assembly system called the “C-system.” This is the considered and measured response that comes from those with emotional intelligence.

When we receive negative social stimuli that engender a feeling of fear or threat, such as during exclusion, bullying or rejection, this activates the same networks in the brain as those activated by physical pain.

While neuro-commandments 1–5 ensure primary survival, we are also programmed to ensure social survival. David Rock says it is important to recognize that human beings have specific SCARF® Drivers and that a threat to any one of them can engender an emotional reaction and activate the accompanying avoid-threat reflex.

• The avoid-threat reflex is caused by us experiencing a sense of danger or pain.

• The approach-reward reflex is caused by us experiencing reward and pleasure.

Rock states that we make such decisions about threat or reward, based on our emotional response, five times every second. This is a very subtle process, and we are making decisions about everything, good or bad, all the time.

Rock’s SCARF® Drivers Model27 provides a framework to capture the common factors that can activate a reward or threat response in social situations. The five domains in the model activate either the “primary reward” or “primary threat” circuitry (and associated networks) of the brain. For example, neuroscience has demonstrated that a perceived threat to one’s status activates similar brain networks to a threat to one’s life. In the same way, a perceived increase in fairness activates the same reward circuitry as a perceived monetary reward.

The five SCARF® Drivers — status, certainty, autonomy, relatedness and fairness — provide an effective tool for exploring how parties in conflict perceive and respond to social situations. To different degrees, impacts on all five domains can influence a person’s perception of a situation and whether they view it as being threatening or rewarding. The needs of people in conflict, and the impact of the conflict on them, can be explored by using the five domains as subjects for exploratory questioning. This is covered in Chapter 16.

The perception of a reduction in status, or an actual reduction in status, can generate a strong threat response in us. In conflicts presenting to mediation, it is quite common for one party or both parties to have an underlying need to have their reputation or status restored. We generate a slight reward response when we perceive that our status has risen, but the threat response we generate when we perceive that our status has fallen is much stronger. Research has illustrated that, within the same subjects, an experience of social rejection and an experience of physical pain activated overlapping neural regions. Experiences of both physical and social pain rely on shared neural substrates.28

The brain is a pattern-recognition machine that is constantly trying to predict the future based on past experiences. Increased ambiguity or uncertainty decreases activation in reward circuits and increases activation in the threat neural circuitry, for instance in the amygdala. When one or more parties have unrealized expectations of the other, or when organizational change takes place, this can be a contributing factor to a conflict presenting to mediation.

In a study by Leotti and Delgado,29 the anticipation of making a choice demonstrated increased activity in the reward regions of the brain. Mediation cases in the workplace can often revolve around unclear job descriptions or a supervisor’s micro-management of an employee, and these can affect a person’s sense of autonomy. The social need for autonomy can arise in all sectors of mediation practice.

This is directly related to whether we feel that we are engaging in safe or threatening social interactions. The phenomena known as “in-group preference” or “out-group bias” refers to the consistent finding that we feel greater trust and empathy toward those who are like us and are part of the same social circles and we feel greater distrust and reduced empathy toward those who we perceive as dissimilar to us, or who are members of other social groups. The definition of in-group and out-group members is not limited to racial, ethnic, religious or political distinctions, but can be seen where a person feels marginalized through bullying or harassment at work or feels excluded in a social or community setting.

The perception of fairness is very important to us in any situation. We do not base this perception on cold or rational thought processes, because emotions are integral to our judgment of fairness. The types of judgment we make evolve over time through our social experiences with others.30 Recent research has shown that the amygdala is activated during the rejection of unfair offers and that receiving or making fair offers activates a reward response. In mediation, the perception or actuality of fair treatment can often be the underlying interest of a party — for example, in civil and commercial mediations.

There are several ways in which the five domains of social experience relate to one another, and how the SCARF® Drivers are impacted will depend on every party’s unique perceptions.

Example:

Experiencing redundancy

When a person is made redundant from work, all five domains of the SCARF® Drivers Model may be affected. Every individual’s reaction to this event will depend on how they perceive their world, which will affect whether they sense redundancy as a threat or a reward.

If Person A feels their status is defined by their job, if he no longer has certainty about his economic survival and if he feels he will lose his autonomy over his earning capacity, he will register an avoid-threat reflex. If he also misses the company of his workmates because he was part of that workforce all of his working life (relatedness), and if he feels that being made redundant is unfair as he personally did nothing to affect the downturn in the economy and its impact on the company, then he will feel negatively affected by the loss of his job.

Perspective of Person B

On the other hand, Person B may perceive the situation completely differently and may be delighted that from now on she can make her own decision (autonomy) about when she gets out of bed in the morning and what she will plan for her day. She may have been counting the years to retirement because she wanted to spend more time with her partner (relatedness) and become better at tennis and beat her friend who is always boasting about her game (status). She may never have liked working in a team with ten others and may have felt stressed because she was never able to forecast accurately how her boss would react to her work output, or even what mood her boss would be in (certainty), and she thinks that the redundancy package that he is being offered is very fair.

When the SCARF® Drivers are activated, parties in conflict feel threatened or rewarded, and this has an impact on their perception of the social situation in which they find themselves. Whether a party in mediation is moved by an approach-reward or avoid-threat reflex will influence their ability to think cognitively and make rational decisions.

In the face of conflict there is no such thing as a cool-headed reasoner. We, in conflict situations, feel and act like prey animals; who have a natural, psycho-biological discomfort and unease about being in foreign terrain and in a circumstance over which we do not have complete control. At worst, we have abject fear of being compromised or injured.

— Antonio Damasio, Van Allen Professor and Head of Neurology at the University of Iowa

This section outlines the need to work with parties’ avoid-threat reflex as a means to reach their underlying needs and interests. Parties in conflict experience a wide range of emotions when they come to mediation: tension, anxiety, fear, embarrassment, uncertainty or worry. Sitting in the same room as the person with whom they are in conflict will probably elicit many other feelings such as anger, frustration, vengefulness, distrust, bitterness, hurt, sadness or regret.

When fear is aroused, empathy vanishes, permanently or temporarily, and the capacity for exploration goes on hold.

— Una McCluskey31

A summary provided by Jeremy Lack and Francois Bogacz illustrates the state of parties presenting to an alternative dispute resolution process, with their positions on the conflict and the other party psychologically firmly in place.

In Positional Dispute Resolution Processes, rather than Interest Based Dispute Resolution processes, the 10 neuro-commandments are likely to be primed negatively due to the inherently competitive or adversarial nature of these processes. The parties will not behave empathetically and will expect to be pressed to make concessions, they will expect and seek to avoid pain, are likely to be dominated by patterns of fear, may have no sense of certainty or predictability due to their perception of the other’s irrational or bad-faith behavior and may be influenced by strong emotions of anger. They are likely to avoid all social interaction with the other party (often professing to speak through their lawyers or using caucus meetings if a mediation has been started), and they may feel their sense of status being questioned or undermined.32

Example:

Having been accused of wrongful behavior, they may become completely incapable of empathizing with the other side (who is viewed as belonging to an adversarial group), may perceive the other as acting unfairly (thus further exacerbating senses of pain or social exclusion), may feel the other party is impinging on their autonomy, and may be rendered incapable of high order C-system cognitive thinking, as dominant emotional neural networks may consume oxygen and glucose and limit their ability for objective and dispassionate analysis.

We are hardwired to be alert to the actions or inactions of others that threaten our well-being or interests. When a party is asked a question, the amygdala in their limbic system scans the question to determine whether it is compatible or incompatible with their interests. A question they perceive as threatening engenders a negative emotional reaction. Their brain registers the emotion, and the neural pathways in the brain interpret its meaning, which prompts them to employ behavior that protects their vulnerability.

They may enter an avoid-threat reflex mode. If this happens, their ability to continue to think rationally will depend on the level of emotional stimulation they received, and on their ability to regulate their emotions, which, in turn, depends on their level of emotional intelligence.

During mediation sessions, it is essential that a mediator has a heightened sense of emotional awareness so that they notice when a party experiences a negative emotional response. In both private and joint meetings, if a party experiences highly negative emotion, the mediator needs to support them to gently move out of an avoid-threat reflex. This can be done by gradually slowing the pace of the discussion, speaking in a quiet, gentle way, listening attentively to what the party needs to say, and being in the moment with that party.

A functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study33 conducted at the University of California in 2007 showed that affect labeling (using words to describe feelings) produces diminished responses in the amygdala and other limbic regions. Therefore, it is important for parties in conflict to have a space to tell their stories through a process in which they will be heard by the mediator at the first separate private meeting, and by the other party at the joint meeting.

The mediator needs to ask questions in a gentle and empathic way, to support the party to label the emotions they feel. The mediator then needs to slowly and gently reflect back the main points of what the party has said, so that they feel heard and have an opportunity to clarify their thinking. It is only when a party has become calmer that the oxygen and glucose required by the amygdala to process their emotions can shift back to the frontal brain to enable cognitive thinking to take place.

Asking questions that translate any threats felt by parties into needs or underlying interests is a way of supporting parties to zone in on the core of their conflict. When a party demonstrates the avoid-threat reflex, identifying what triggered this reflex and its accompanying emotions is the key to getting to the heart of the conflict and to a party’s conscious or unconscious concerns, fears and underlying interests.

All conflicts are perceived by the senses, manifested through body language and kinesthetic sensations, embodied and given meaning by thoughts and ideas, steeped in intense emotions, made conscious through awareness, and may then be resolved by conversations and experiences.

— Kenneth Cloke34

The positions adopted and stated by the parties are the gateway to their underlying interests. It is important to note and explore the positions of people in conflict and to use these identified positions, with their accompanying displayed emotions, to get to what lies beneath them. It is by addressing these unseen layers that conflict can be transformed effectively and sustainably.

Chapter 16: Underlying Interests Questions describes the methodology used to get to both the conscious and unconscious underlying interests of parties. Using these methods enables a mediator to support parties to be coherent and congruent about what they wish to say at mediation. In exploring the deeper level of communication between parties, the task of the mediator is to ask questions that will find the unique perspective and paradigm of the parties and the positive intention behind their actions. A mediator’s task is to bring the thoughts, assumptions, concerns and fears of the parties from the internal to the external. This should surface any misperceptions, misinterpretations and misunderstandings between parties that may have occurred. These methods are comprehensively covered in Chapter 16.

When underlying interests have been explored and labeled, and when the parties hear and understand the perspective of the other party, it can lead to a paradigm shift in the thinking of both parties, and their approaches to each other. When people have had a chance to talk and vent about their conflict issues, they are ready to hear the other party speak as they will feel less threatened and will be able to think cognitively. This paves the way for an effective and sustainable resolution to be found. A solution that has emanated from merely exploring the positions held by parties may only lead to short-term and topic-specific solutions.

Once parties have understood each other, it is fruitless for a mediator to continue to focus on the past for any longer than is necessary, because this may activate the avoid-threat reflex unnecessarily, lead to amygdala hijack and keep the parties on the treadmill of blame and attack. People find it hard to change their past negative narrative that they have lived within for what may have been years of conflict. This process takes time accompanied by evidential behavioral change. All it takes is for one party to repeat something from the old narrative, such as, “He really should not have done that,” to set the other party off with a defensive response. However, it is important to stay in the past long enough to facilitate the parties to vent their feelings and identify their underlying interests and needs.

When no new information or insight is to be gained, asking S4: Future Focus questions from the S Questions Model is a way of changing the negative state and narrative of a party to a more positive narrative with options and possibilities. This will help them to create a future without the problems of the past and will activate their approach-reward reflex. When safety and certainty about the future seem more possible, parties are more open to agreeing on a way forward.

While S4: Future Focus questions are covered comprehensively in Chapter 17, it is important that the value of these questions in mediation be mentioned at this juncture.