(For background information, refer to the theoretical input in Chapter 3: Working with the Brain in Mediation.)

Figure: 16.1.

CREDIT: O’SULLIVAN SOLUTIONS

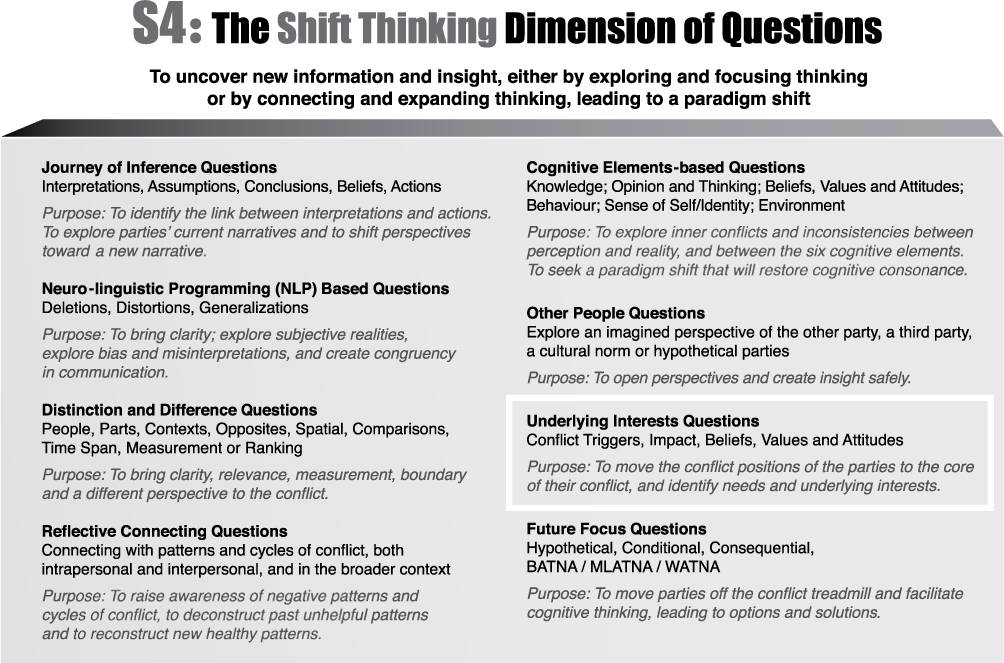

UNDERLYING INTERESTS QUESTIONS delve beneath the conflict positions and demands presented by parties in mediation. They are designed to reach the core of their conflict and discover the things that are important to them. Getting to the underlying interests introduces new and valuable information to a mediation process and creates new insight and understanding between parties in conflict. This in turn should lead to a paradigm shift in their thinking and approach toward the conflict and toward each other.

When the needs and underlying interests of parties have been identified, they will feel more understood, be able to think cognitively and therefore be ready to move to identifying sustainable solutions that meet their underlying interests. Once the underlying interests have been reached, there is no need to remain focused on the parties’ past experiences for any longer than is necessary. However, it is important to discuss the past for long enough to facilitate parties to vent their feelings, explore their underlying interests and then use these past experiences as a platform from which to identify and explore options for the future.

Prior to exploring how to unearth the underlying interests of a party, it is necessary to look at what is meant by the mediation terms issue, position and underlying interest.

Issue

An issue is the subject matter of the conflict that requires resolution.

Position

A position is the stance a party takes to the conflict in which they are involved. This is the place from where they rationalize their situation and then act and react. When a party is feeling vulnerable, the position they take may become fixed and will be their way of protecting that vulnerability. There is a need to draw a distinction between a position and a fixed position. Adopting a position is not in itself problematic, but when a party sticks firmly to their position, then the situation becomes more difficult to solve.

The position taken by a party may include:

■ Defending themselves by blaming the other person

■ Making demands, such as saying, “Either she goes or I go!”

■ Insisting on an apology

■ Continuing to believe that the other party wants to damage them, even when evidence contradicts this belief

An underlying interest is a conscious or unconscious need or vulnerability within a person that they protect by taking a position or stance to protect themselves. It is this deep-down need or fear that informs and drives the stance or position that a party adopts in conflict. The motivation to protect these underlying interests may be caused by a threat to the values or beliefs that are very important to them, or to their SCARF® Drivers of status, certainty, autonomy, relatedness or fairness.

The positions adopted and stated by the parties are the gateways to their underlying interests. It is important to note and explore these identified positions, with their accompanying displayed emotions, to get to the underlying interests of a party. It is by addressing these unseen layers that conflict can be transformed effectively and sustainably.

When people engage in mediation, they begin with their narrative fully embedded and demonstrate this narrative with the conflict position that they take. The positions adopted and stated by the parties, and the emotions they display, are the key to uncovering their underlying interests. Exploring what is beneath a party’s position is what will lead to increased understanding for both parties and to an appropriate, sustainable and effective resolution.

Asking Underlying Interests questions sensitively, and with integrity, helps parties to identify and verbalize their emotions. Chapter 3 described the concept of affect labeling: if people verbalize their emotions, this produces diminished responses in their amygdala and other limbic regions. It is crucial to facilitate parties to verbalize their emotions so that they can then start to think cognitively before exploring any possible options or agreements.

These questions are used:

✓ When parties hold steadfastly to their conflict positions and demands

✓ When a mediator needs to move the parties beyond their conflict positions to the root cause of their negative emotions

✓ When a mediator is unsure of the reason and the extent that a conflict situation has impacted on a party

✓ When parties do not understand why the conflict is causing them such inner stress

✓ When the emotional distress of a party is blocking progress in the mediation

✓ To facilitate parties to gain new insight and understanding

✓ To get to the core of the conflict to identify the underlying interests of the parties so that appropriate and sustainable solutions that match these underlying interests can be found

While Chapter 4 contains generic guidelines for asking questions, there are additional specific guidelines for Underlying Interests questions.

At the initial separate meeting, assess the appropriateness of asking Underlying Interests questions, before asking a party these questions during a joint meeting.

■ Do not ask one party about their underlying interests until both parties have told their stories and have vented their anger or negative emotions; otherwise the party who has not yet been heard will not be willing or able to listen cognitively.

■ If a party seems incapable of expressing empathy for the other party, then exercise caution about exposing the vulnerability of either party.

■ Do not push parties past their comfort zone as not all parties may wish to delve into deeper areas.

■ Work with parties in a way that is appropriate to the field of mediation by facilitating them to find a future without the problems of the past. Do not begin to take on the role of a counselor or psychotherapist.

■ If parties do not need to have a relationship with each other after mediation, this might reduce the need to explore underlying interests fully; however, it may still need to be done if reaching an agreement is dependent on the parties having a deeper understanding of what went wrong in the past.

1. Use appropriate body language

2. Signpost and set the tone for asking Underlying Interests questions

3. Gently reflect back what you are hearing at the start of the process

4. Facilitate the expression of emotions, unobtrusively

5. Identify and use the last words voiced by a party

6. Recognize the difference between positional statements and underlying interests statements

7. Recognize underlying interest feelings within positional statements

8. Support a party who is hesitant to reveal their underlying interests

9. Be aware of the indicators that demonstrate that underlying interests have been reached

10. Work with knowledge of the avoid-threat reflex

11. Ask S4: Future Focus questions after the underlying interests of both parties have been explored

1. Use Appropriate Body Language

Use body language that will indicate nonverbally to a party that the tone of the mediation is going to change:

■ Put any notes or notepad away.

■ Ensure that you are seated and lean in toward the party, but do not move into their intimate space.

■ Lower the level of your voice and speak gently, slowly and quietly.

2. Signpost and Set the Tone for Asking Underlying Interests Questions

Prior to exploring underlying interests, the mediator signposts what they are going to do next:

I am going to ask each of you how this conflict has impacted on you. I would like to ask Jean some questions, and I would like you, Dan, to really listen, and then I will do the same with you, Dan, and I will ask Jean to listen.

3. Gently Reflect Back What You Are Hearing at the Start of the Process

At the start of the process of exploring underlying interests, a mediator needs to reflect back what was said by the party prior to asking another question. However, as the discussion becomes more exploratory and deeper, the need for reflecting back what you have heard is greatly reduced and a mediator need only reflect back an important feeling word such as “devastated,” or just nod their head. To do otherwise would interrupt the party’s flow of thoughts. The mediator, in that quiet and deeper space, needs to be completely in the moment with that party so they can go on their journey of thoughts, feelings and explorations.

4. Facilitate the Expression of Emotions, Unobtrusively

If a party is not comfortable expressing their emotions, then asking them directly about how they are feeling may be seen as intrusive by them, and they may feel threatened and block the conversation. In this case, there may be a need to translate questions about feelings in a way that is seen by parties as being less touchy-feely or intrusive,

Examples:

■ How were you affected by that?

■ What was it like for you when that happened?

■ What reaction did that generate in you?

■ What was the worst thing about all of that for you?

■ What has been the impact on you?

■ What is the one word that would adequately describe the impact on you when that happened?

5. Identify and Use the Last Words Voiced by a Party

When parties are describing their experiences, the last words they use before they stop talking can often be their own unconscious summary of their truth, what has happened, what is important to them and how they are feeling about it. This can be a gateway to their underlying interests and can be used to formulate the next underlying interests question:

Example:

Party:

...and that was why I made the complaint, I couldn’t take it anymore.

Mediator:

■ You mention that you could not take it anymore, what was it that you could not take any more?

■ What was it like for you to be in a place where you say you could not take it anymore?

6. Recognize the Difference Between Positional Statements and Underlying Interest Statements

A positional statement is blaming and demanding and is usually delivered with negative emotions and body language. On the other hand, an underlying interest statement illustrates how a person is feeling about what has happened, and what the impact has been on them. It is usually delivered in a quieter manner.

Example:

There is a difference between when a party says “I can’t sleep” using an aggressive and positional tone, and when they use the same words — “I can’t sleep” — quietly and calmly, as an expression of the difficulties they are experiencing in the conflict.

Examples of Differences Between Positional Statements and Underlying Interests Statements

Statement |

Approach |

Words |

Positional statement |

Blames and demandsUses aggressive body languageUses sharp and loud tone of voice |

I JUST CAN’T SLEEP ANYMORE! SHE SHOULD GET ON WITH HER OWN WORK AND STOP BOTHERING ME!!!! |

Underlying interest statement |

Describes the impactUses gentle but firm body languageUses quieter and softer tone of voice |

I just can’t sleep anymore and feel frightened when she comes toward me with a question, because I might not know the answer — this is causing me a lot of stress and sleepless nights. |

The reason it is important to identify the difference between a positional statement and an underlying interest statement is that sometimes when a mediator starts to explore underlying interests, a party can easily slip back up into a positional stance and the opportunity to continue to bring them down to underlying interests may seem to be lost.

To manage this, and only after the parties have had time to vent their feelings, a mediator needs to ignore the positional language statements and gently bring the party back to their underlying interests statements:

Mediator: You mentioned that you are not sleeping, what is that like for you?

Party: It’s devastating (said in a quiet voice) AND IT’S ALL HER FAULT (said angrily)

Mediator: In what way is it devastating?

Party: I am exhausted every day and can’t manage the work. SHE HAS TO STOP!

Mediator: What is it like for you to feel exhausted and not be able to manage your work?

...and continue until underlying interests are reached and the party has become noticeably calmer.

7. Recognize Underlying Interest Feelings Within Positional Statements

Underlying interest feeling statements may be contained within positional statements or interspersed within the narrative of a party. It is important to listen carefully for feeling statements that might indicate underlying interests so that they can be captured and used in questions to get beneath the positional level of a party.

Example of a party expressing an underlying sentiment within their positional statement:

Party:

She should not have done that! This is not normal behavior and I have never come across anything like it before. I felt completely powerless! This is outlandish behavior and would not be tolerated anywhere else.

Mediator:

You mentioned that you felt completely powerless ... powerless in what way? What has this been like for you? How has it impacted on you? What was the worst thing for you about feeling powerless? What were you worried about for the future?

8. Support a Party Who Is Hesitant to Reveal Their Underlying Interests

In some cases, a party may not feel comfortable expressing their underlying interests in front of the party with whom they are in conflict. It is very important to not pressure them on this issue. But in some instances, the parties may have had a previous relationship, and reaching underlying interests may increase understanding between them.

Examples:

■ Dan, I note that you are not comfortable about opening up opposite the other party; what is it that concerns you? What are you worried about?

■ What might you lose by not saying it? What might you gain by saying it?

■ How important is it to you that understanding be created between you? What mark out of 10 would you rate this importance?

■ What are all the ways in which your concerns about opening up could be alleviated?

■ What would you need to know or understand from the other party before you would feel comfortable? If you had that assurance from them, how would it help? What might you need to ask from the other party so you would feel comfortable about opening up?

9. Be Aware of the Indicators That Demonstrate That Underlying Interests Have Been Reached

You will know that the underlying interests of parties have been reached when a party is no longer acting from their original positional state, has become less positional and cathartically quieter in their tone, starts to use fewer words or responds in a monosyllabic manner.

Example:

After several questions to bring to the surface underlying interests, a party may indicate a final emotion by just saying, “It… was… devastating.”

Or they may even respond by merely nodding their head and staying silent as a means of acknowledging that the mediation questions have reached the core of their problem and they have nothing more to say. If you think that the underlying interests have been reached, and that there is no new insight to be gained, then just remain silent to give both parties time to reflect on what has been said. One of them will take the initiative to speak when they are ready. Often it is the party who has been listening that starts to contribute. They may start by saying how shocked they are to hear what has just been said, that they had no idea of the impact on the other party, etc. It is very important that the mediator captures this immediately and reflects it back to the party whose underlying interests have been reached so that it has the required impact. This is done effectively by the mediator looking at that party while reflecting back what the other party has said.

10. Work with Knowledge of the Avoid-threat Reflex

Once underlying interests have been reached, refrain from focusing on the past for any longer than is necessary as this may activate the avoid-threat reflex and result in an amygdala hijack. All it takes is for one party to repeat something from the old narrative, such as “He really should not have done that!” to spark the other party into responding defensively and counterattacking, and if this is allowed to grow and fester, it will unravel all the good work that has been achieved. It may just take a few seconds to unravel but could take two hours for a mediator to bring the parties back on track again!

You might say that surely if underlying interests have been uncovered effectively then this should not happen, and you would be right to do so as it could mean this that this needs to be checked out. However, when parties have lived within a narrative for many months or years of conflict, it takes time before they start to trust each other and let the old narrative go. In other words, they are still protecting themselves to a certain extent as they have no concrete evidence yet that things have changed, so a mediator needs to ensure that once underlying interests have been reached that past emotions are not inadvertently or unnecessarily raised, risking a deviation from the journey of building a new and alternative narrative.

11. Ask S4: Future Focus Questions After the Underlying Interests of Both Parties Have Been Explored

Once parties have vented their emotions, underlying interests have been identified and understanding has been reached, and there is no new information or insight to be gained, a mediator needs to switch to asking S4: Future Focus questions to find the way forward and create a new narrative. It is very important that this is managed tightly, as a party can easily slip back into their former negative narrative, which will result in the conversations going around in circles without a conclusion.

Future Focus question example:

You mentioned that this was a very difficult time for you, and you said you were very worried that you would lose your job and not be able to keep up the mortgage repayments and provide for your family … what needs to be put in place now so that you have a firm agreement that will ensure that you no longer have these worries?

S4: Future Focus questions are covered in Chapter 17, the next chapter.

The underlying interests of a party may be conscious and easy to identify, or may be unconscious and require additional methods to discover them.

It is the role of the mediator to facilitate parties to be clear about what they wish to say in mediation. When a party is at a strong positional level, this is when their negative emotions are displayed, and it is beneath these negative emotions that their unsaid underlying interests can be discovered.

There are many layers of underlying interests beneath a party’s position. Asking parties what attaining their positional demand will give them may be sufficient to reach conscious underlying interests. However, in some situations, a party may not know their underlying interests, as these remain at their unconscious level, so unearthing them may not be quite so easy. The presence of unconscious underlying interests will be demonstrated by a party’s confusion about the unexpected impact the conflict has had on them.

Parties may say things like:

■ I cannot believe the impact this is having on me! I don’t know what is going on!

or

■ I can’t see any way out of this. It’s all completely hopeless.

Unconscious or less obvious underlying interests need additional methods. These methods ask parties about the event that triggered their response when they first became aware that there was a conflict, what negative emotions arose for them as a result of the trigger, what SCARF® Drivers were impacted or how their values or beliefs seemed to be threatened.

Question tasks for uncovering Underlying Interests: Both conscious and unconscious

Conscious underlying interests Generic questions |

Unconscious underlying interests Additional questions |

Conflict positions? |

Conflict trigger and the emotional response to it? |

Impact? |

Impact on SCARF® Drivers? |

Emotions? |

Values and beliefs? |

Concerns/worries? |

|

Conscious needs? |

|

The time that passes from when the amygdala detects a threat to the time a party adopts a position is only a split second. A party’s positional demands are usually voiced as a protection mechanism and often disappear when their underlying interests have been voiced and heard and when understanding has been reached between parties.

The type of position that a party takes is influenced by their past experiences of conflict, the way they view conflict and the values and beliefs they have formed. This is the place from where they rationalize their situation and react. The positions they take are their negative expressions of what they really need: what they determine will protect them.

Conscious underlying interests Generic questions |

Conflict positions? |

Impact? |

Emotions? |

Concerns/worries? |

Conscious needs? |

The above questioning methods do not always need to be used in the order in which they are listed here, but their use needs to be relevant to the particular discussion that is taking place.

Generic Questions

You can explore beneath a party’s positional statement by asking about what their positional demand could give them if it was met:

Party: I want him sacked immediately! (Positional statement)

The mediator then looks for underlying interests by asking what a party’s positional demand could give them, if it was met:

Mediator: If your boss was sacked, what would this give you? What specific needs of yours would be addressed?

Party: Then the bullying would stop. (Underlying interest)

Mediator: If the behavior of your boss was different, what would that give you? Specifically, what do you need from your boss?

When parties are asked about the impact a conflict has had on them, this facilitates them to start talking about the emotional aspect of the conflict, which can be the gateway to identifying the core of their conflict.

Examples:

■ Will you tell me a little about the impact this has had on you?

■ How would you describe this impact?

■ What exactly was impacted?

■ In what way was it impacted?

■ What has been the worst thing about this impact on you?

■ What are you worried might happen if this impact continues into the future?

Parties need to be asked what emotions surfaced for them during the conflict.

Examples:

■ What was all this like for you?

■ How were you affected by it?

■ What was the main feeling response that you had?

■ What was the worst thing about this for you?

■ What is the one word that could describe your feelings?

Parties need to explore their concerns or worries.

Examples:

■ What are the concerns or worries you have had around this, both now and for the future?

■ What are your priority concerns?

■ What is the depth of your concerns? 0 = not deep and 10 = very deep

■ What was it about this concern that made it a particular worry for you?

■ What were you worried might happen at that time?

■ What specifically are you worried about right now?

■ What are you worried might happen in the future?

Parties can be asked about any of their needs that were not met.

Examples:

■ What needs of yours were not met at the start of the conflict? What needs are not being met now? What needs are you worried may not be met in the future?

■ Can you identify the level of importance of each need and the reason you give it this level of importance? What might happen if your most important needs are not addressed?

■ In what other ways could your needs be met? (Note: other than by their positional demands)

■ What would be the outcome for both of you if these needs were met?

To identify and reach unconscious underlying interests, there are some additional specific methods that can be used.

Unconscious underlying interests Additional questions |

Conflict trigger and the emotional response to it? |

Impact on SCARF® Drivers? |

Values and beliefs? |

Identify the stimulus or triggering event that resulted in a party’s disproportionate negative emotional response. When we have a sudden and disproportionate emotional reaction to a stimulus, this brings to the fore the fact that another’s values, beliefs, needs, interests, assumptions or perceptions are incompatible with ours. Then support the party to identify the connection between this stimulus and their reactions, and to explore the emotions that surfaced for them as a result of the stimulus.

Identify whether there has been any impact on any of the SCARF® Drivers of status, certainty, autonomy, relatedness and fairness (David Rock). These drivers can then be used as questioning subjects for exploring unconscious needs.

Explore the values and beliefs of the parties to ascertain what is important to them and identify what has actually been impacted or threatened, or what they perceive to have been threatened.

These three methods do not always need to be used in the order in which they are listed here. Choose a method depending on the areas of discussion that are taking place between the parties.

Examples:

■ If a party has started to describe the impact on one of their values, then asking questions about this impact on their beliefs and values, followed by questions regarding any loss from this, would be appropriate at that time.

or

■ If a party is talking about how the conflict started, then asking conflict trigger questions would be more appropriate.

The rest of this chapter has examples of questions that can be asked for each of the three methods to identify the unconscious underlying interests.

A conflict trigger is an event that results in a sudden and disproportionate emotional response in a person. This emotional response indicates that something of fundamental value to the person is perceived to be, or is, under threat. Identifying the trigger for this threat response, with its accompanying disproportionate emotional response, will provide a gateway to get to the underlying interests of a party.

The less emotionally intelligent and self-aware we are, the harder it is for us to avoid feeling threatened by a stimulus, regulate our emotions and access our cognitive thinking during conflict.

Our responses to conflict triggers are determined by our perceptions and our life experiences. A party’s disproportionate emotional response comes from their unique vulnerability or sensitivity. This sensitivity is known as a hot button. A conflict trigger cannot be a trigger if there is no hot button response to a stimulus. When we are feeling a response to a trigger, we can unconsciously make a judgment that this other person’s values and beliefs may not be compatible with ours.

Exploring the response to conflict triggers facilitates the surfacing of the emotions, concerns, worries or values of parties that may have been impacted. Taking the party back to the event that triggered the conflict, and then asking gentle exploratory questions about their triggered response, will identify the core of what may be affecting them. Exploring the underlying interests of a party moves them from their fixed positional level to connecting with the experience of their original reaction. This is where joint understanding can be created.

Here are examples of questions to explore conflict triggers to reach unconscious underlying interests.

These questions can be asked around the impact on the party, the emotions that surfaced for them, their worries and concerns and their needs.

Subject matter |

Mediator’s questions |

Reflect back what was said |

Jean, you mentioned earlier that you felt threatened by the way in which Dan responded to you... |

Conflict trigger |

When did you first feel threatened, or know that there was tension? What was it that Dan said or did that evoked that reaction in you? |

Impact |

When you first felt threatened, how did that impact on you? What was impacted that was important to you? What is the one word that would describe it? |

Emotions |

What thoughts came up for you when that happened? What might have been theemotions behind those thoughts? To what specifically did you find yourself reacting? What did this raise for you? What else did it bring up for you? What was that like for you? About what did you have the strongest reaction/feeling? What is the one word thatwould describe it? |

Worries and concerns |

When that happened, what did you become concerned or worried about? What was important to you about this? What was your biggest challenge, worry or concern? What is the one word that you would use to describe this? |

Needs |

What does this say about your needs? What specifically did you need at that time? When Dan responded to you like that, what needs of yours were not being met? What do you need now? |

An additional method to discover unconscious underlying interests is to explore with the party any underlying unconscious interests that may have been impacted or threatened, or perceived to be threatened, based on David Rock’s SCARF® Drivers of status, certainty, autonomy, relatedness and fairness. This is an effective tool to identify any unconscious needs that may have been threatened.

(Refer to Chapter 3 for a recap on SCARF® Drivers)

Examples of questions using SCARF® Drivers to identify underlying interests:

SCARF® Driver: Status

It is quite common for either or both parties in a conflict to have an underlying need for their status to be respected or restored. An expected, perceived or actual loss of status often results in a feeling of threat or anxiousness, leading to an avoid-threat reflex.

Scenario: Aggressive behavior in the workplace:

■ May I take you back to the time this happened; you mentioned that when your boss shouted at you, that you felt undermined. What was it like to feel that you were undermined? What did this raise for you? How did it impact on your sense of yourself and who you are?

■ What was this like for you? What were you most worried about? What had you needed most at that time?

After underlying interests have been reached:

■ What do you need now so that you no longer feel undermined and your sense of status is intact?

The brain is a pattern-recognition machine that constantly tries to predict the future, based on past experiences. If what is happening does not meet a person’s expectations, then this can impact on their level of certainty.

Scenario: Expectations versus uncertainty:

■ When this happened, what did it bring up for you? What was this like for you?

■ What had been your expectations?

■ How did those expectations compare with what happened?

■ What was the most important thing missing for you? What was this like for you?

■ What is it like for you to feel uncertain?

■ And what is that like? How is this impacting on you?

After underlying interests have been reached:

■ What do you need for the future to ensure that your expectations meet the reality of what might happen?

SCARF® Driver: Autonomy

Issues about a lack of autonomy and self-determination can cause conflict and result in a person feeling out of control, threatened, frustrated or stressed.

Scenario: Business partnership where one partner makes decisions without consulting the other:

■ When that happened, what was that like for you?

■ What control did you feel you had lost?

■ What concerns you most about this? How is this for you? What is it like for you to feel this way?

■ What needs of yours are currently not being met?

■ What might be the long-term impact if this continues?

After underlying interests have been reached:

■ What conversations do you need to have with the other party to ensure that your needs with regard to consultation will be understood and met?

The degree to which we feel a sense of connectedness, similarity and security with those around us can be linked to whether we feel safe or threatened.

Scenario: Relationship breakdown between work colleagues:

■ What was it like for each of you when this blew up and you started to pull away from each other?

■ What emotions did this raise for each of you?

■ What did each of you most need from the other at that time?

■ What relationship needs of yours were not being met as the conflict escalated?

■ What worried you most about all of this?

■ How bad was this worry for you? Rank it from 1 to 10, with 10 being a really serious worry. What influenced you to give it that ranking?

■ What do you most miss from the relationship?

After underlying interests have been reached:

■ What is needed to get back that trust and to what you miss most in the relationship with each other?

SCARF® Driver: Fairness

The perception of fairness in any situation is not based on cold rational thought processes, but on emotions, which are integral to our judgment of fairness. Neuroscientific research has shown that the amygdala registers a response when we consider that an unfair offer has been made.

Scenario: Commercial negotiation regarding monetary compensation:

■ What was it about this that you considered to be unfair?

■ What criteria do you use to judge fairness? How would you rank these criteria in order of priority?

■ How is what is happening meeting or not meeting your criteria? In what way?

■ What is important to you about fairness? If things are not fair, how is this for you? How does this impact you? What is this like for you?

■ What is the one word you would use to describe it?

■ What is your most important need around this?

After underlying interests have been reached:

■ If your need about fairness was satisfied, what could you offer to the other party in return?

As stated, when parties perceive or experience that their values and beliefs are not compatible with another’s, or when they feel these have been infringed or threatened, this will result in them experiencing an avoid-threat reflex.

We value people, behaviors and events positively if they promote or protect the attainment of the goals we value. We evaluate them negatively if they hinder or threaten attainment of these values goals. Values are critical motivators of behaviors and attitudes.

— S. H. Schwartz45

The type of position that a party takes is influenced by their past experiences of conflict, the way they view conflict and the values and beliefs that they have formed. This is the place from where they rationalize their situation and react. However, when parties start to hear the values behind the other’s position as a result of questions being asked, they may start to understand that what is beneath the other person’s displayed position may not actually pose a threat to them after all.

Definitions of Values and Beliefs

Before giving some examples of questions that can be asked, it is important to cover some theory related to values and beliefs.

Values: A value is a measure of the worth or importance we attach to something. Internalized values reveal themselves in behavior, but professed values may exist only in words. Therefore, to identify the truth of a value, there may be a need to explore behavior and to facilitate the parties to make links between what they say is a value and the actions that they are taking.

Beliefs: A belief is an internal feeling that something is true or correct, even if it may be unproven or irrational.

Formation of Our Values and Beliefs

Our values and beliefs are formed by:

• Our experiences during our formation;

• The way our parents or guardians modeled their values and beliefs to us;

• Our culture, education, religion or anything else that influenced us to become who we are.

We may choose to adopt or reject these values and beliefs from our formation, but either way, we will have been influenced by them, even if it was by fighting against them.

Examples of the formation of our values and beliefs:

Values: If a parent has consistently impressed on a child that they must always help others and never say No to anyone, that child may decide to accept their parent’s values about this, and they may find it difficult to say No to a request later in life, even if this request impacts other values.

or

They may reject this value, but either way, they will have been influenced by it.

Beliefs: If a child falls from a horse, they may develop a belief that “Nothing is going to beat me in life and I am going to get up on that horse again!”

or

They may believe that horses are dangerous and decide to never get up on a horse again.

Examples of questions for exploring values and beliefs:

Scenario: Gender transition:

Joe (Joanne) is eighteen years old. He was raised as a girl but always considered himself male and for the past two to three years has been exploring the possibility of transitioning. He has come out to friends and family and has generally found acceptance, but his mother, Louise, has totally refused to believe that his situation is genuine. She attributes his “confusion” to the fact that his father died when he was twelve, an event which traumatized him greatly, and believes that he is trying to replace this absent male parent.

Louise is very concerned about what the extended family will think if Joe (Joanne) goes ahead with the transition. Louise and her family are very, very religious and have highly principled morals and values, and this screams against everything she believes in. Joe (Joanne) is about to go to college to study architecture, and Louise is threatening to withdraw financial support if he doesn’t do as she wishes. Joe has approached his uncle, Louise’s brother, for help, and he has advised mediation. Louise has agreed to try it.

After talking for a while about the situation she is facing, Louise ends with this statement to the mediator: “Joanne will get over this; the less said the better.”

Mediator:

Louise, you mention that this is a difficult time for you and that you think Joanne will get over it. You also mention that you and your family are very religious and highly principled and that this goes against your values ….

Reflecting on the conflict trigger:

■ When Joanne told you about this, what was that like for you?

■ To what did you find yourself reacting? What did this invoke in you? What was it like for you when this happened?

Reflecting on the values and beliefs:

■ What are your beliefs about transitioning?

■ When you talk about values, what do you mean, can you tell me a little more?

■ What is it about this particular value that is very important to you?

■ You say this undermines everything you consider to be moral, or that you value or believe to be right. What is the most important thing about all this for you?

Hearing the concerns, worries and impact:

■ What is challenging you the most? What is it like for you to face this challenge? What is it like for you when your child wishes to do something that you believe is wrong?

■ How are you coping with all this worry?

■ You talk about losing your reputation within the family; will you tell me a little more about this worry?

■ What is the worst thing that could happen?

■ You mention you would be devastated if Joanne decided to leave home and not talk to you anymore.

■ If this happened, what would be your biggest worry or concern about it?

■ You say that you would miss Joanne as you love her very much. You also say you would be worried about how the world would treat her if she goes ahead with these operations because you believe this to be wrong, and others might agree with you and give her a really tough time. And you say that if only Joanne would not go through with this operation, that you would be able to protect her…

■ What is it like for you to believe that Joanne could leave home as a result of how you feel about her wishes and that she could have a tough life because of her choice and that you would not be there to protect her?

Other values:

■ What are the values you hold about being a parent to your children? And what are your values about a parent/child relationship? How important are these values to you? On a scale of 0 to 10, with 10 being high value, where would you rank it?

■ How would you rank the importance of your values to you about what Joanne wishes to do?

■ Louise, you say you are now struggling with these two values being mutually exclusive and clashing with each other…

■ What might be the outcome if you hold tight to your value about it not being right that Joanne transitions? What might happen if you were to let this value go?

■ What might be the outcome if you hold onto your value about parents and parent/child relationships being so important to you?

■ What might happen if you were to let this value go?

■ What are your overall conclusions at this stage, Louise?

Introducing a possible future narrative:

■ What would it be like for you if it was one year from now and you had been able to find a way through this that would have met the values and needs of both you and Joanne?

■ What overarching value would you have created that would have helped you to deal with this clash of values — one where you are not struggling with your religious beliefs as well as not worrying that Joanne might leave home and have a very tough life?

■ What would you both have needed that would have helped each of you?

■ You mention that the shock of all this has been difficult for you, but that if Joanne waited a year before starting the transition, this would help you to get used to the idea and to talk to your family about it without any rush or pressure.

■ How would it be for you to have this conversation with Joanne in mediation?

Values-based conflicts can be the most difficult conflicts to manage. But there are some other methods that may help:

1. Translate values into needs and then ask needs-based questions

2. Create increased understanding between the parties

3. Look for commonalities

4. Discuss the effects of holding or losing this value

1. Translate Values into Needs and Then Ask Needs-based Questions

■ What is it that you need from each other that you are not getting?

■ What is important to each of you about this need?

■ What is it like when you don’t have this need satisfied?

■ What exactly do you need? How could this need be met?

■ If you had this need satisfied, what would it give you? What could you offer to Joe (Joanne)?

2. Create Increased Understanding Between the Parties

At appropriate times during the mediation process, it is important to ask each party to hypothesize about what may have been going on for the other party (S4: Other People questions), because if one party observes from this exercise that the other party understands them, it can help them to shift their thinking and not remain so entrenched. However, caution needs to be exercised about this as the mediator needs to know that the responses from a party to this question, while the other party is in the room, will not fuel the conflict further. Therefore, the questions may need to be asked privately first.

Use S4: Other People questions to increase understanding:

■ What might Joanne have observed about you during your struggle with this issue?

■ How could you help Joanne to understand what this has been like for you?

■ What else might Joanne need you to know to be able to fully understand you?

■ With what might each of you be struggling in trying to understand the other?

■ If you were in Joanne’s shoes, with her thoughts and feelings, with what might you be struggling?

■ What might be important for each of you in all this?

3. Look for Commonalities

If it is not possible to create understanding between parties, then look for commonalities between them and use these as a basis for reaching solutions for at least some parts of the dispute, if not all parts.

Example:

You both say that you did not manage this well; if you were to go back again with the knowledge you have now, what might each of you do differently?

How could this learning be included in an agreement?

4. Discuss the Effects of Holding or Losing This Value:

■ What is it about this that is important to you?

■ What would happen if this value was threatened?

■ What does the holding of this value give you? What does it not give you?

■ What is the cost to you of holding onto this value? What would it take for you to let this value go? With what could you replace it? How could this be managed?

■ What could change so that you do not feel that your value is under threat? What would that be like for you?

If a values-based conflict is not completely resolved, then accept and acknowledge that this is the case. When understanding has not been reached at underlying interest level, then any agreements made when parties are still at positional level need to be teased out thoroughly. Agreements made without reaching underlying interests need to be comprehensive and detailed to ensure that every eventuality is covered. They need to be vigorously reality tested to guard against any misinterpretations post-mediation.

As the emotions of a party who is still in a “positional” stance may still be high, one of the ways of supporting them to think cognitively is to ask S4: Future Focus questions. These questions change the state of the parties from one of hopelessness and annoyance to one of cautious possibility.

Example of a Future Focus question:

Imagine it is one year from now and the needs of both of you have been addressed, what would have happened that would have caused this outcome? What would each of you have done to have made that happen? What would have changed about your relationship with each other that would have allowed this to happen?

Once underlying interests have been reached, refrain from focusing on the past for any longer than is necessary as this may activate the avoid-threat reflex and result in an amygdala hijack. However, it is important to stay in the past long enough to facilitate the parties to vent their feelings and identify their underlying interests. The past can then be used as a platform from which to gather information about the future needs of the parties.

S4: Future Focus questions from the next chapter can be asked at this stage to tease out options for agreement. These questions change the “state” of a party and enable them to shift from their old narrative to a new one. This will facilitate them to activate an approach-reward reflex mode, think cognitively and create solutions.