Figure: 14.1.

CREDIT: O’SULLIVAN SOLUTIONS

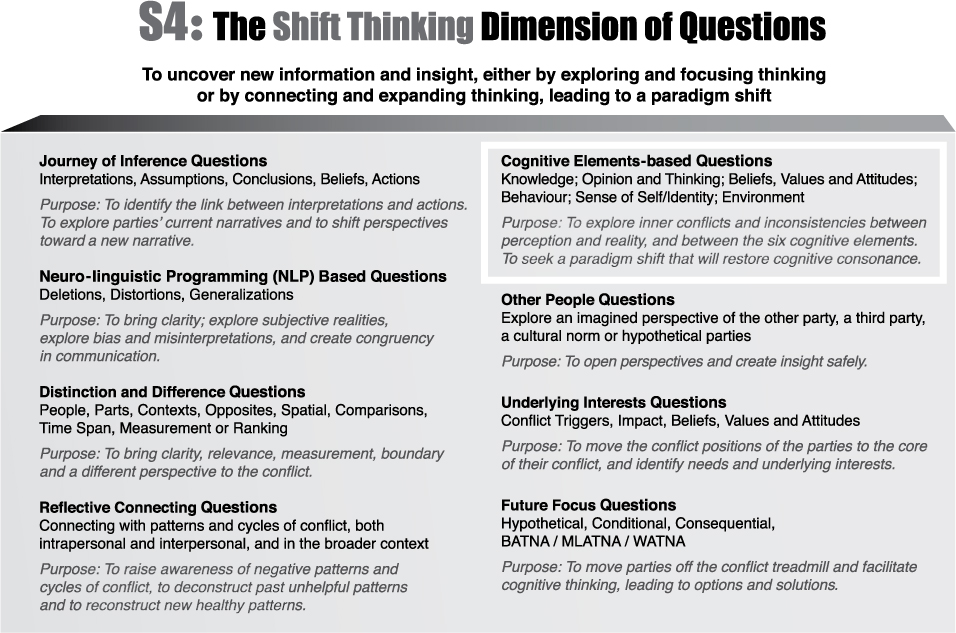

COGNITIVE ELEMENTS-BASED QUESTIONS explore inconsistencies (cognitive dissonance) between our cognitive elements, which are: our knowledge; our opinions and thinking; our beliefs, values and attitudes; our behaviors; our sense of self or identity; and our environment. These questions explore the psychological conflicts that result when one or more of our cognitive elements are in dissonance with another cognitive element, simultaneously.

Example of cognitive dissonance:

When I know (cognitive element: knowledge) that smoking is damaging to my health, but I continue to smoke anyway (cognitive element: behavior).

Chapter 3 illustrated how biological hardwiring, governed by memories of stimuli, activates an avoid-threat reflex in us. Our life experience demonstrates to us that when we react with an avoid-threat reflex, we are correct to do so, as it reduces the sense of threat that we experience. But when this correctness is shaken or challenged, it creates uncertainty in us and we enter into a state of cognitive dissonance.

Before moving to the methodology of developing Cognitive Elements-based questions, it is important to look at some background theory first, including the definition of cognitive dissonance and an explanation of each of the cognitive elements.

The theory of cognitive dissonance was developed by Leon Festinger43 in 1957. He defined it as a psychological conflict which results when one of our cognitive elements is incongruent with another element, simultaneously.

Cognition is any knowledge, opinion or belief that we have about our sense of self or identity, or our behavior, or our environment.

Cognitive dissonance and cognitive consonance refer to relations that exist, simultaneously, between any pair of elements of cognition, such as between our beliefs and what we experience in our environment; between our knowledge and our beliefs; or between our opinion of ourselves and our actual behavior.

For cognitive dissonance to exist within a person, there needs to be a relation between a pair of cognitive elements.

Example of a relation between the cognitive elements of belief and behavior:

If we have a very strong belief about equality between the sexes, but we also value making a profit, then we may experience dissonance between our belief in the equality of the sexes and our behavior of strategically hiring an older woman because she will not need maternity leave and will therefore be less costly to us. In this instance, our beliefs, values and attitudes and our behaviors have a relation with each other and are in dissonance with each other, simultaneously. When two or more cognitive elements are incongruent with each other, we experience dissonance, are thrown out of balance and then strive to return to harmony and cognitive consonance.

Cognitive consonance occurs:

a) When there is no relation between a pair of cognitive elements.

Example:

Beliefs, values or attitudes: I believe that the world is round. Behavior: I bought an ice cream today.

b) When there is a relation between a pair of elements, but they are congruent with each other, simultaneously.

Example:

Beliefs, values or attitudes: I believe it is very important to take care of those who are elderly and living alone.

Behavior: My elderly neighbor lives alone, and I call to visit her daily.

Festinger’s theory focuses on how people strive for internal consistency and balance. When they experience inconsistency (dissonance between the elements of cognition), individuals tend to become psychologically uncomfortable and are motivated to attempt to reduce this dissonance, as well as to actively avoid situations and information that are likely to increase it. Festinger suggests that we are driven to hold all our attitudes and beliefs in harmony (consonance), and to avoid disharmony (dissonance).

Festinger worked from two basic hypotheses:

• That the existence of dissonance, being psychologically uncomfortable, will motivate a person to try to reduce that dissonance and achieve consonance.

• That when dissonance is present, as well as trying to reduce it, a person will actively avoid situations and information that would be likely to increase the dissonance.

Before moving to the methodology to use when asking Cognitive Elements-based questions, we need to first look at the following:

1. Determinants of the presence of cognitive dissonance

2. Magnitude of cognitive dissonance

3. Blocks to reducing cognitive dissonance

4. The strategies we may use to defend against experiencing cognitive dissonance

5. Post-decision cognitive consonance

The amount of cognitive dissonance in parties will fluctuate throughout the course of a mediation, and will be dependent on:

■ Whether the type of question that is asked of a party results in any feelings of threat;

■ Whether one party says something that will affect the cognitive consonance of the other party;

■ Whether the parties start to understand each other, or not, as a result of increased knowledge;

■ Whether the parties start to problem-solve together as a result of attitudinal change;

■ Whether one party makes a positive gesture to the other;

■ Whether the parties have made any positive agreements with each other around future behavior; etc.

The magnitude of cognitive dissonance we experience is related to:

■ The degree to which any cognitive element is inconsistent with another cognitive element;

■ How important we consider the conflicting cognitive elements to be;

■ How highly we value a specific cognitive element.

When we experience cognitive dissonance, we strive to reduce or eliminate this dissonance or threat. The strength of the pressure needed to reduce the dissonance is related to the magnitude of the dissonance. As the magnitude increases, the pressure to reduce dissonance increases. The maximum dissonance that can possibly exist for a person is equal to the total resistance to change of the less resistant element.

There are several reasons why we may find it difficult to change elements of cognition so that we achieve cognitive consonance:

■ The change may be painful or may involve loss

Example:

I have a good social life with friends and I really enjoy their company, but if I want to stop smoking then I will have to avoid all social occasions for a while so I am not tempted to smoke.

■ The decision that resulted in cognitive dissonance may be difficult to revoke

Example:

If I regret selling my home last year, then I cannot un-sell it.

■ If changing one of the elements results in cognitive dissonance with another element

Example:

If my employer says that I should not wear a hijab, and if my religious beliefs or culture advocate that I must wear a hijab, then I will experience dissonance if I obey my employer. If I try to reduce this dissonance by leaving my job as a legal intern, then I will create cognitive dissonance between my cognitive element of behavior in leaving and my cognitive elements of beliefs, values and attitudes, as I believe that the best way that I can become a good lawyer and defend human rights abuses is by staying with this company.

When observable data contradict our interpretations, assumptions, conclusions and beliefs, we experience cognitive dissonance. This could happen to a party that we take through a series of S4: Journey of Inference questions. They will then seek to achieve cognitive consonance as quickly as possible to regain their comfort about what is happening to them. If dissonance is not reduced by changing one of the cognitive elements, a party may restore consonance through misperception, blaming others, rejecting the information they are faced with, attempting to persuade others to understand their point of view or by seeking support from others who share their beliefs.

We create our falsehoods by filtering information and deleting, distorting and generalizing the information that we absorb, as evidenced in Chapter 11. Over a lifetime, we develop a range of tools and skills for reducing cognitive dissonance when we are conflicted.

Example:

We justify smoking cigarettes by saying:

There is a far higher chance that I will be killed by a car, than by the few cigarettes that I smoke.

To achieve cognitive consonance, the CEO may employ any of the following strategies to either eliminate or reduce this cognitive dissonance:

a) He could change one of his original conflicting cognitive elements of belief or behavior.

b) He could change the level of importance of one of his cognitive elements.

c) He could add a new cognition to one of the conflicting elements of belief or behavior.

d) He could make a decision that will achieve cognitive consonance later.

a) He could change one of the conflicting elements of belief or behavior:

■ He could strengthen his original cognitive element of belief that excessive micromanagement is necessary for high productivity and then his cognitive element of behavior would change.

or

■ He could learn (CE: knowledge) from his colleagues that pressurizing employees only makes matters worse as employees becomes stressed by it and cannot function effectively and work productively. Therefore, he will change his cognitive element of behavior.

b) He could reduce or decrease the importance of one of the conflicting elements of belief or behavior by changing his perception of his behavior or his belief:

■ He could continue the bullying behavior by completely denying to himself that his behavior causes any harm to his manager cognitive elements of belief.

or

■ He could strengthen his belief that the whole system will fall apart and productivity will go down drastically if he lessens control over his manager. Therefore, his behavior will match his belief.

c) He could add a new cognition to one of the conflicting elements of belief or behavior:

■ He could add a new cognition to his behavior and decide to only criticize the manager in private because his daughter told him that being bullied in front of others in the classroom was the worst part of her experience.

or

■ He could add a new cognition to his belief that persuades him that adults and children are not the same:

She is only a child, but my manager will just have to toughen up, really.

d) He could make decisions (behaviors) that may achieve cognitive consonance later:

■ If the existing cognitions cannot be changed, and a new cognition cannot be added now, then behaviors that may favor consonance in the future might be agreed. The CEO could decide to participate in a management training course to learn what the industry norms are regarding the link between management style and productivity.

If the CEO decides to change either his cognitive element of belief or his cognitive element of behavior, or to not change any of his cognitive elements, he will then only absorb information that confirms this belief or behavior he has chosen and will avoid any contradictory information so that he remains in cognitive consonance.

Once parties have made decisions and reached agreement in mediation, after reality testing, and when they have successfully achieved cognitive consonance, it is difficult for them to change their minds, as this may increase cognitive dissonance for them again. This is particularly important to note with regard to the mediated agreements that the clients of mediators agree and sign.

Once people have made a decision, they usually start to reduce any postdecision dissonance in the following ways:

a) By decreasing the attractiveness of the options that they did not choose, and by seeking more positive information about the options that they did choose. This proves to them that they have made the correct decision.

b) By perceiving that some of the characteristics of the options they have chosen are the same as some of the characteristics of the options they did not choose, thus reducing the dissonance.

c) By increasing or decreasing the importance of various aspects of the options chosen, in line with the decisions that they made.

If parties are already experiencing cognitive dissonance, or if a mediator decides to strategically work to produce cognitive dissonance in a party, then the party will tend to become psychologically uncomfortable and will be motivated to attempt to reduce this dissonance and disharmony and return to harmony and cognitive consonance.

Cognitive Elements-based questions bring any inconsistencies between a party’s cognitive elements to a conscious level and challenges that perspective and paradigm. A mediator can work with this dissonance and facilitate a party to explore the cognitive elements that are in dissonance so that they can get to the root of their inner conflict, and then facilitate them to identify the appropriate changes that will result in them achieving cognitive consonance and harmony again.

Cognitive Elements-based questions are used:

✓ When it is unclear what motivates or guides a party’s approach or behaviors

✓ When inner conflict or disharmony may exist within a party

✓ When a party is unable to progress to reaching agreement

✓ When a party is strongly defending their position and this conflict perspective is inhibiting movement toward a solution

✓ When the stated or apparent impact on a party seems greater than that which would have been expected under any given circumstance

✓ To facilitate the parties to make connections with their cognitive elements so that their perspective is expanded

✓ When a mediator needs to strategically challenge one of the cognitive elements (e.g., behavior or beliefs) of a party because that party’s current behavior is impacting negatively on the conflict dynamic

Chapter 4 contains generic guidelines for asking questions, but there are additional specific guidelines for asking Cognitive Elements-based questions.

In asking Cognitive Elements-based questions, it is very important to not expose any vulnerability of one party in front of the other party. If you think that a party may be vulnerable, test out any Cognitive Elements-based questions, either at the initial separate private meeting or during a private meeting during the joint session.

✓ It is important to ensure that a party has told their story and has had an opportunity to vent their emotions about their situation before asking challenging Cognitive Elements-based questions.

✓ Ensure that questions are delivered in a nonjudgmental way, with gentle, open and respectful body language, as a party may easily become defensive, particularly if they have low self-esteem.

✓ Do not pressure a party to answer a question — proceed carefully and gently, at their pace, and with their permission. Should you inadvertently touch on any past trauma of a party, then slowly and gently name the fact that you have touched on it, acknowledge that it must have caused deep pain, and then ask what needs to be in place to address their conflict issues for the future.

✓ When cognitive dissonance has been created, the mediator needs to ensure that the parties will be brought to cognitive consonance with whatever decisions are made. This is where the role of reality testing the mediation agreements is very important.

We can work with Cognitive Elements-based questions in two ways:

1. To proactively trigger cognitive dissonance

2. When a party displays cognitive dissonance

There may be times when a mediator needs to strategically choose to trigger cognitive dissonance and a negative emotional response from parties. This needs to be done using respectful and gentle body language.

For example, when a party states one thing, but their actions contradict it:

It often happens that separating couples engage in mediation and state loudly and forcefully that the most important thing to them is the welfare of their children. Then they start to metaphorically kill each other and try to block the other parent from spending time with their children.

Mediator proactively triggers cognitive dissonance:

I have observed that you both say very clearly that the most important thing to you is the welfare of your children. I have also observed that you are both finding great difficulty in meeting the needs of your children if it means that one of you needs to give something to the other. What might be going on for each of you when you are like this? Can you help me understand?

Cognitive Elements-based questions can also be asked of a party who has either displayed or expressed inner uncomfortableness or contradiction.

In both of the above circumstances, questions are introduced that raise the premise that one or more elements of cognition within a party may not be harmonious with another element. The questions asked need to first build and hold cognitive dissonance in the parties. Then the motivation within the parties to reduce this dissonance and to achieve cognitive consonance will increase. Having worked with, or created, dissonance, the mediator then needs to work with the party to restore cognitive consonance or harmony. The challenge for a mediator is to ensure that cognitive consonance is reached in a helpful way for both parties.

Step 1: Bring attention to the cognitive dissonance

Step 2: Build and hold cognitive dissonance

Step 3: Reduce cognitive dissonance and work toward cognitive consonance by facilitating the party to:

a) Change one of his original conflicting cognitive elements of belief or behavior

b) Change the level of importance of one of his cognitive elements

c) Add a new cognition to one of the conflicting elements of belief or behavior

d) Make a decision that achieves cognitive consonance later

Step 4: Support the party to look at options and reach solutions for the conflict that will achieve cognitive consonance and be in the best interests of both parties.

(CE: cognitive element)

Mediator reflecting back:

■ Rebecca, you mention that you are a strong believer in fairness and that you always did everything to ensure you were fair to your staff. You mention that because the recession has impacted your business greatly, you are now doing things that you would not have considered fair before the recession — will you tell me more about this?

These questions create and build dissonance:

■ How is it for you when your actions (CE: behavior) contradict what you think is right (CE: beliefs, values and attitudes)?

■ What is it like for you to be in this conflict now with Sarah, who you say you value highly?

■ What are all the questions that you may have been asking yourself about this? What is it like for you to be in this dilemma?

■ How might Sarah be feeling about all this?

■ What might happen if this is not sorted?

Cognitive dissonance can be reduced by using one of the following methods.

a) Party could change one of the original conflicting cognitions (e.g., belief or behavior)

Change in beliefs and values:

■ Giving marks out of 10, how important is it for you to hold onto this belief or value? 10 = very important and 0 = no importance. What gives it this importance for you?

■ Given the circumstances of the recession, how fair are you being toward yourself in trying to uphold your belief in fairness? Marks out of 10?

■ What might set your mind at ease about it?

■ What did you hope to achieve with this action (CE: behavior)?

■ How is it meeting your beliefs and values? How is it not meeting them?

■ What are all your options around changing your actions (CE: behavior)?

■ How might a business colleague put your actions (CE: behavior) into context? What might they advise you? How would you advise yourself?

In conclusion, what are all the options that are open to you so that your belief around fairness and your actions are compatible with each other? With what options might you be more comfortable?

b) Change the level of importance of one of the cognitions

■ How important is it for you to continue with this belief in this context? 0 = not important, 10 = very important.

■ How important is it for you to continue with this action that you needed to take in this context? 0 = not important, 10 = very important.

■ What does this tell you?

■ What might help you to reduce/increase the importance of your belief so that you are more comfortable with your actions (CE: behavior)? How could this be managed?

■ What might help you to reduce/increase the importance of your action so that you are more comfortable with your beliefs? How could this be managed?

c) Add a new cognition to one of the conflicting elements of belief or behavior

■ What might happen if you were to change how you thought (CE: opinions and thinking) about all this?

■ What information (CE: knowledge) is out there that could help you to modify your belief in fairness in some way?

■ Is there any new information (CE: knowledge) to be gained that could change your views of your action?

■ Is there another belief (CE: belief) that could override your belief in fairness?

■ What is this conflict between your beliefs and your behavior doing to your sense of yourself (CE: sense of self/identity)? How would you rate the importance to you of each of these cognitive elements: beliefs and values; behavior; sense of self/identity; opinions and thinking? What does this say to you?

d) Make a decision that achieves cognitive consonance later

■ Is there a period of time during which you would be prepared to modify your belief until the recession ends?

■ What would happen if you put an end date on your actions and requests of Sarah and informed her of this end date?

■ What are all your options?

■ What would each of your options give you? Not give you?

■ Which option would help to settle the inner conflict that you talked about?

■ What would it be like for both of you if this was achieved?

• S4: Journey of Inference questions challenge interpretations and assumptions and can be used in exploring or creating cognitive dissonance.

• S4: NLP-based questions around the area of distortion help parties to think about their thinking.

• S4: Underlying Interests questions are helpful in exploring the cognitive elements of beliefs, values and attitudes. Chapter 16 includes options on what a mediator can do if they reach an impasse when working with a party’s values.