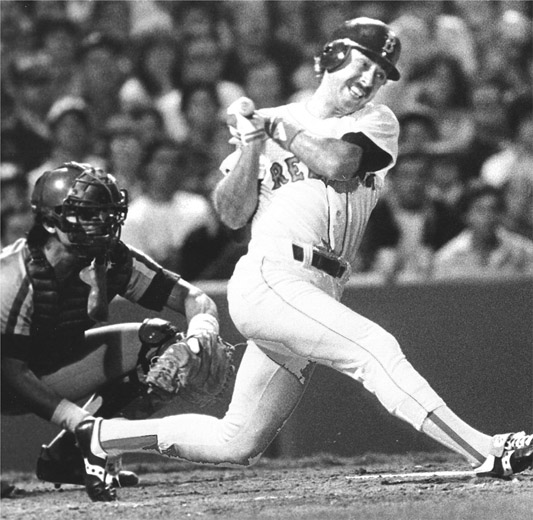

The catcher’s glove is closed and my mouth is open, which means I probably swung and missed.

Photo courtesy Boston Red Sox

C H A P T E R S E V E N

Not every hitter can hit every type of pitch, thrown to any location in the strike zone. And not every pitcher cooperates by throwing a hittable pitch on any particular count in an at bat.

But a smart batter can increase the chances of getting a pitch he can hit by working the count to situations in which the pitcher really needs to throw a strike. The goal is to try to get into a hitter’s count, giving the batter the luxury of being able to look for a particular pitch in a particular location.

There are some batters who may see only a few pitches per at bat; they come out of the dugout swinging. And then there are guys who average six or seven pitches each time they’re up to bat. Batters who see a lot of pitches tend to receive many walks and have good on-base percentages.

In order to work a count, a batter is going to be down in a lot of counts. These hitters are not afraid to take strikes, and they’re not afraid to be up there with two strikes on them.

Many of the hitting mistakes made by players come when they are in a hitter’s count, but they don’t narrow down their zone enough. In other words they are swinging at a strike, but it is not their strike. It is not where their strength is.

Across the course of a season or a career, a hitter will almost always be more successful when he manages to work the count to his advantage. A hitter is “ahead” in the count when the pitcher has thrown more balls than strikes: 1–0, 2–0, 2–1, 3–0, and 3–1.

Conversely, the batter is “behind” in the count in 0–1, 0–2, 1–2, and 2–2 counts. There’s a lot to be learned—and admired—in looking at Boston’s two most successful hitters for the 2007 season, David Ortiz and Mike Lowell.

Big Papi led the Red Sox in the regular season with a .332 batting average and 35 home runs; he drove in 117 runs. Mike Lowell was close behind for the season, batting .324 and clubbing 21 homers; he led the team with 120 RBIs.

Let’s look inside those numbers:

|

Ortiz |

Lowell |

|

|

Season batting average |

.332 |

.324 |

|

BA with RISP |

.362 |

.356 |

|

BA ahead in the count |

.358 |

.356 |

|

BA ahead in the count with RISP |

.392 |

.385 |

|

BA behind in the count |

.246 |

.235 |

|

BA behind in the count with RISP |

.206 |

.298 |

|

BA with no outs |

.317 |

.308 |

|

BA with one out |

.352 |

.348 |

|

BA with two outs |

.332 |

.312 |

|

BA: batting average; RISP: runners in scoring position. |

||

What can we learn from these two exceptional hitters? First of all, we can see their value in the lineup. These guys make the most of their opportunities to drive in runs.

Both Ortiz and Lowell bat about thirty points higher when they come up to the plate with runners in scoring position, and both are even more successful when they get ahead in the count. Both are also quite good at maintaining their batting average even with two outs against them; the count matters more to them than the number of outs.

Finally, we can see how important it is—for the opposing pitcher—to try to get ahead of Ortiz or Lowell. The numbers drop off for both, but Lowell shows solid numbers even when he is in the hole.

From the pitcher’s point of view, there’s a story line behind each pitch in an at bat. One pitch is often thrown to try to set up the batter for another. When the pitcher is ahead in the count—at 0–2, for example—his goal may be to get the batter to chase something way out of the strike zone; in another situation, such as 3–2, in most cases the pitcher is going to throw something he’s pretty sure he can get into the strike zone.

Across a five- or six-pitch at bat, the seesaw battle between the pitcher and batter offers counts where one or the other may have a bit of an advantage. A smart pitcher—and his catcher—knows the story line that goes with each count. A smart batter turns around the pitcher’s mind-set to try to choose the counts when he may get the pitch he wants to swing at.

Here’s a tour through each of the possible pitcher’s counts in an at bat, starting with “neutral” counts, 0–0 and 1–1 .

Pitchers are urged to stay ahead in the count and try to get a strike with the first pitch; for some pitchers that means throwing a fastball, while others with good breaking pitches may try to throw something out of the zone that a batter will chase.

Some batters are ready to go on the first pitch. On 0–0 Nomar Garciaparra was looking for something over the plate, whether it be a fastball or a breaking ball. Wade Boggs was known for taking the first pitch, but every now and then he would let it fly, especially if the pitcher believed too much in the scouting report and threw a batting-practice fastball to open the at bat.

Kevin Youkilis and Dustin Pedroia share the same trait: neither is likely to swing at the first pitch, doing so only about 10 percent of the time.

But, in general, it all comes down to the individual batter and the pitcher he is facing. For example, if the man on the mound is wild and has a tendency to walk a lot of opponents, a hitter probably shouldn’t plan on swinging at the first pitch. The idea is to give him a chance to be wild.

Now, let’s say the pitcher has thrown eight balls in a row, walking the last two batters. A coach might want to put the take sign on: Make the pitcher throw a strike, don’t help him out. But in the back of the hitter’s mind he is saying: “This guy just threw eight balls. He is going to try to throw a strike here and there’s going to be nothing on it.” So the batter may be ready to swing.

When I was facing a pitcher struggling with control and the pitching coach made a visit to the mound, I felt that I pretty much knew what he was being told: “Just throw strikes. Make him swing the bat, and we’ve got guys ready out there to catch the ball for you.” So as a hitter, I could reasonably expect he was coming right down the middle with his next pitch.

The first pitch came in, and the batter either swung at it unsuccessfully or couldn’t get to a tough strike. The count is now 0–1. The batter doesn’t want to fall behind 0–2, so if the pitch is on one of the corners, he is probably going to swing at it.

Now the pitcher’s strike zone expands a little bit; that doesn’t mean that the umpire’s calls will change, but instead that the batter may be a little less selective.

To me an even count of 1–1 is the same as 0–1. The batter wants to avoid ending up with two strikes on him.

This is a situation in which the hitter doesn’t have the same flexibility he has with a 1–0 count. He’s got to cover a little bit more of the plate, but again he doesn’t want to swing at a nasty strike because he still has a chance at 1–2.

Let’s say the pitcher throws a changeup on this count to a fastball hitter; in that situation the batter should not swing. But if he gets a fastball in the strike zone, he should take a hack because nobody wants to be down two strikes.

A batter deep in the hole at 0–2 or 1–2 is living on borrowed time. He’s got to cover the plate and swing at anything close to try to make contact. He doesn’t want to leave it in the hands of the umpire on a close pitch.

For a batter who doesn’t strike out much, an 0–2 or 1–2 count may not be that bad. But a two-strike count is not good for a power hitter or a player who chases bad pitches.

“Hitting is 50 percent above the shoulders.”

TED WILLIAMS

These counts offer the pitcher the opportunity purposely to throw something off the plate, trying to get the batter to chase a pitch out of the strike zone. With a count of 0–2 or 1–2, a pitcher usually considers wasting a pitch to see if the batter will cooperate and get himself out.

Once again, on a 2–2 count the pitcher doesn’t have to throw a strike; he still has some room to work with. You may see the pitcher come in with his best strikeout pitch, or he may throw a waste pitch out of the strike zone.

In this situation the batter is a little more sure in the box because he’s already seen at least four pitches, and he may have fouled off a few more. But he still has to protect the plate to avoid striking out.

Now here are the counts that favor the batter. The pitcher has either missed with his first pitch or intentionally wasted a pitch to try to get the batter to swing at something outside the strike zone. At 1–0 the count favors the hitter. The pitcher does not want to fall behind 2–0, so the batter is expecting him to try to throw a strike. He is ready to swing.

What the batter gets, of course, depends on the pitcher. Is it going to be a fastball? Or will it be a curveball, a changeup, or a slider? That’s why pitchers like Pedro Martínez are so great. The batter never knows what they are going to throw on any count. With many pitchers, on a 1–0 count it would be reasonable to expect a fastball. But Martínez might throw a changeup.

From the pitcher’s point of view, if he just missed a strike with the first pitch, sometimes he’ll try to nibble at the strike zone with the same pitch, hoping the batter will lay off.

Now comes the question: take a strike or swing? If the batter is leading off the inning, he might want to take a pitch here and hope to draw a walk. On the other hand, if the batter has power, this pitch might be a good one to take a rip at.

If the pitcher misses again and falls behind 2–0, this is a real hitter’s count. Here’s where a batter can get real choosey, based on his knowledge of his own strengths and weaknesses. On this count the hitter’s goal should be to narrow his zone to a location and a pitch he has a good chance of hitting well. For most batters that means a pitch they can pull.

Let’s say he is a power hitter, strong from the middle of the plate in, and he can get the most on a ball that is just below the belt. And let’s say he prefers a fastball to a breaking ball. The batter picks a zone and looks for the pitch he wants. If the pitch is in the zone and something he can catch up with, he swings; if it is away or too high or too low, he lets it go by.

If a batter doesn’t see his pitch, he should not swing because he is almost as good with a 2–1 count as he is at 2–0.

When the pitcher is all the way in the hole, with a 3–0 count, you might think this is the perfect hitter’s count, but that’s not always the way it works. When some batters are given the green light on a 3–0 count, they get so anxious and excited at the prospect of a fat pitch over the plate that they don’t know how to handle it. They will swing at anything.

For that reason, and because the manager may be just as happy getting a base runner with a walk, most hitters are instructed to take a pitch on 3–0. Guys like me were never told to swing on 3–0.

There’s not really a “green light” in this situation; it is more a matter of taking away the red light. The manager has to learn which guys he can trust hitting 3–0. It is almost always power hitters—guys who have the ability to hit home runs—who are allowed to swing on this count. The batter should be one who has the ability to identify his zone; if the pitch is not in that zone, he doesn’t even think about swinging.

Depending on the game situation and the batter, a pitcher with a 3–0 count may just lay in a fat, hittable pitch. A guy who ordinarily throws at 95 miles per hour may step it down to 90 or 91. That’s still moving, but it is nothing like his strikeout pitch.

Knowing the Count

|

Count |

Hitter’s count |

Pitcher’s count |

The batter expects |

Batting averagea |

On-base percentageb |

|

0–0 |

Neutral count. High percentage of fastballs. Some batters, like Ted Williams, argued that batters should take the first pitch. Tell that to Nomar Gar-ciaparra. |

.340 |

.345 |

||

|

0–1 |

✔ |

Pitcher’s choice. Batter is in a defensive situation and may be less aggressive |

.325 |

.335 |

|

|

0–2 |

✔ |

Protect the plate. The pitcher often throws a breaking ball or a waste pitch. |

.165 |

.180 |

|

|

1–0 |

✔ |

Expect a fastball. Focus on favorite zone. |

.345 |

.345 |

|

|

1–1 |

Neutral count. Pitcher can throw any pitch. |

.330 |

.335 |

||

|

1–2 |

✔ |

Protect the plate. Often a breaking ball count. |

.185 |

.190 |

|

|

2–0 |

✔ |

Expect a fastball. Focus on favorite zone. Excellent hitter’s count. |

.370 |

.370 |

|

|

2–1 |

Expect a fastball. Excellent hit-and-run count. |

.345 |

.345 |

||

|

2–2 |

✔ |

Protect the plate. Expect pitcher’s best strikeout pitch, often a breaking ball. |

.200 |

.200 |

|

|

3–0 |

✔b |

Expect a fastball. Focus on favorite zone. |

.430b |

.960b |

|

|

3–1 |

✔ |

Expect a fastball. Focus on favorite zone. Excellent hitter’s count and run-and-hit count. |

.345 |

.690 |

|

|

3–2 |

Pitcher wants a strike. Expect a fastball if the pitcher does not have command of breaking ball. |

.240 |

.240 |

a Based on analysis of 2000–2002 MLB seasons

b Usually only the best hitters are given a green light with a 3–0 count, while most batters are told to take a pitch in hopes of receiving a walk. The expected highest batting average for most batters comes with a 2–0 count, followed closely by a 1–0 situation. The highest on-base percentage for most batters is the 3–0 count, because the chances of getting a fat pitch to hit or one outside the strike zone for a walk are high.

To a batter being ahead 2–1 is similar to a 1–1 count. He’s protecting the plate to try to avoid ending up behind in the count with two strikes. At the same time the pitcher is trying not to fall behind 3–1, so the batter is probably going to get a pretty good pitch to hit.

This is what I call an action count. It’s a good pitch for the manager to call a hit-and-run or a squeeze. The pitcher is likely to throw a strike; he is not likely to pitch out or throw an unhittable waste pitch.

The hitter may or may not get a fastball here, but the pitcher does want to try to get the pitch over the plate on this count.

A 3–1 count is another hitter’s count, and also an action count. Once again, the hitter wants to narrow his zone and not swing at a pitch out of the strike zone or one he can’t drive well.

The manager might want to call for a run-and-hit play here. With a 3–1 count, he is not going to put on a hit-and-run because he doesn’t want the batter to be forced to swing at a pitch that is a ball. With a run-andhit play, the batter is given the option of not swinging if the pitch is not a strike.

On a run-and-hit, the base runner takes off on the pitch, and it is up to the batter whether or not to swing. If it is a strike, the coaches want the batter to swing; if it is ball four, the hitter should take the pitch and not chase a ball.

On a 3–2 count the batter is probably going to see a pretty good pitch because the pitcher doesn’t want to issue a walk. He is likely to throw whatever he thinks he can get over the plate. In this situation the pitcher is battling as much as the hitter is.

You are likely to see a pitcher’s nastiest stuff on a 1–2 or 2–2 count. When the count is full, at 3-2, he wants to make sure he throws a strike. So that makes this a much better hitting count than the others.

When a batter is in the hole—with two strikes against him—he’ll usually adjust his swing to try to avoid striking out; coaches call it protecting the plate. It’s mostly a matter of cutting down on the swing to try to improve the chances of making contact.

In other words a batter’s swing should be different with two strikes than if he is ahead in the count. Players who don’t protect the plate are usually guys who strike out more than a hundred times a year.

A good two-strike hitter has excellent hand–eye coordination. He has the ability to lay off a tough pitch, put it in play, or foul it off. The best at this are probably inside-the-baseball hitters.