1974: Henry Kissinger, Muhammad Ali, T. J. Clark

In the fall of 1974, I was an eighteen-year-old sophomore at the State University at Albany. I was an indifferent student, but my engagement with literature, art and politics was deepening. For example, I bought at the Strand Bookstore in Manhattan – but did not actually read – a remaindered copy of Walter Benjamin’s Illuminations. And I read, but did not understand, Herbert Marcuse’s Eros and Civilization. Critical theory was not yet on my horizon. Like many others of my age, I was furiously opposed to the Vietnam War – now a decade old – and brimming with hatred for my country. The Watergate hearings the previous spring, followed by Nixon’s resignation, had been the highlights of my life, and I despaired only that the president’s perfidy was not revealed before his trouncing of the sainted George McGovern in the 1972 elections. Even prior to Watergate, however, my family and I, living in the Jewish enclave of Forest Hills, Queens, had a profound hatred for Nixon and his Rasputin, Henry Kissinger. Joseph Heller summarized our antipathy and shame in 1976 in his novel Good as Gold, when he called Kissinger ‘a moral defilement’ and staged the following exchange between ‘the Governor’, a stand-in for Nelson Rockefeller, and the author’s protagonist, a middle-aged English professor named Gold, with ambitions to become secretary of state: ‘Gold, every Jew should have a big gentile as a friend, and every successful American should own a Jew. I’m big Gold, and I am willing to be your friend.’ Scholarship, like radical politics, is motivated by resentment as much as the spirit of enquiry, and hatred of Nixon and Kissinger undoubtedly spawned more than one academic career.

In 1974, I did not need the Frankfurt School to teach me about the intersection of culture and politics. My sports idol, Muhammad Ali – whose first championship bout against Sonny Liston in 1964 I heard on a radio console in my family living room – was a figure who, because of his Muslim faith and opposition to the draft, occupied both the news and sports pages of the New York Times, and his championship fight against George Foreman in Kinshasa, Zaire, in October 1974 (‘the Rumble in the Jungle’) was as political as much as it was about boxing. Foreman’s flag-waving antics following his 1968 Olympics victory – the games in which Tommie Smith and John Carlos made their Black Power salutes – was to me unforgivable, so I was naturally jubilant when, in spite of all predictions, Ali knocked out Foreman in the eighth round.

At Albany that year, I took courses with, among others, Ann Sutherland Harris, a connoisseur of Italian baroque art, and an expert on the versatile but insipid painter Andrea Sacchi. Harris was impatient in the classroom; she often projected more than a hundred slides in her fifty-five-minute volleys, many of them upside down or sideways. I also studied with Robert D. Kinsman, a professor of modern art who was both punctilious and insightful in the classroom. He had studied with Meyer Schapiro at Columbia in the late 1950s and conceived of works of art as riddles or dreams that required long and patient explication. (Like many of the great man’s pupils, Kinsman had not completed his dissertation on Ozenfant, Le Corbusier and L’Esprit Nouveau, and he left behind few scholarly traces, apart from an exhibition catalogue from 1963 devoted to Jimmy Ernst.) We used as our textbook George Heard Hamilton’s Painting and Sculpture in Europe: 1880–1940, in the Pelican History of Art series, which inspired me. The book has many limitations, not least its teleological structure (abstraction is made to seem the preordained aim of modern art), and its bizarre portmanteau chapter titled ‘Other Schools and Masters’, which strings together German Dada, Max Beckmann, Egon Schiele, Paul Klee, Gerhard Marcks, Rik Wouters, Giorgio Morandi and Henry Moore, among others. But unlike Fritz Novotny’s prior volume in the Pelican series, Hamilton’s book was actually filled with ideas, not merely descriptions and sources. (One forgets these days how truly terrible was most of the scholarship on modern art before the 1980s.) It was also in 1974 that I read Schapiro’s great article ‘The Apples of Cézanne: An Essay on the Meaning of Still Life’, published six years earlier in the ARTnews Annual, and gained an inkling that art history could address both the dynamics of form and psychology. ‘In [Cézanne’s] habitual representation of the apples as a theme by itself’, Schapiro wrote, ‘there is a latent erotic sense, an unconscious symbolizing of a repressed desire.’ 1

Meanwhile, two thousand miles to the west at University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), there arose for the first time an institutionalized version of radical or Marxist art history, a type of scholarship that had previously been practised only sporadically and without official sanction in New York with Schapiro, in London with the émigrés Frederick Antal, Arnold Hauser and Francis Klingender, and in Paris with Henri Lefebvre. In Los Angeles, however, under the leadership of Otto Karl Werckmeister it became the house style. Werckmeister, a German from Berlin with rebarbative manners and an annihilating intellect, was appointed chair in 1971 and immediately began a Robespierrean purge, determined to force his department colleagues to be free. He supplanted the four old boys who previously ran the place and initiated a regime of radical democracy – for example, granting full department voting rights to graduate students as well as to junior faculty. He also fostered, as Carol Duncan described to me, ‘a culture of intellectual confrontation’ that became notorious in a discipline renowned for its good manners.

Werckmeister hired the radical feminist Duncan as a visiting professor in 1973, the year she published in Artforum her iconoclastic essay ‘Virility and Domination in Twentieth-Century Vanguard Painting’. There she argued that, for all their supposed originality, the Fauves and Expressionists relied upon the most trite of clichés: that women are either weak vessels or femmes fatales, and that the avant-garde male artist must by rights exercise his authority – either actually in the studio, or virtually on the canvas – over the bodies of women. These artists’ vaunted freedom, articulated by means of ‘large and spontaneous … painterly gestures’ and a ‘barely controlled energy’, as Duncan wrote, was in fact merely the expression of the ‘fantasies and fears of middle-class men living in a changing world’.2

Though by outward signs no feminist himself, Werckmeister clearly approved of Duncan’s work. Her conclusions were aligned with his own conviction, stated in his 1973 article ‘Marx on Ideology and Art’, published in New Literary History, that the ‘semblance of [art’s] autonomy … was in fact contrived to serve particular interests of socially organized material production…. The historical investigation of art, like that of any other human product, is bound [required] to go beyond its confines and reach the basis of these conditions.’3 Rejecting the theory of ‘non-simultaneity of the development of material and artistic production’, found in Mikhail Lifshitz’s Karl Marx’s Theory of Art, Werckmeister insisted that putatively leftist critics had falsely imputed ‘notions of social progress and historical critique’ to works of modern art, thus severing them from their actual material base. Duncan, who in 1973 also published in the Art Bulletin her article ‘Happy Mothers and Other New Ideas in French Art’, exploring the impact of natalism on late-eighteenth-century paintings of women, shared her UCLA department chair’s insistence upon the need for a rigorous examination of art’s social base and the need to challenge its supposed autonomy. Neither Werckmeister nor Duncan, in sum, believed that works of modern art could significantly advance politics – or indeed even cogently represent it – in the absence of an organized mass movement. That view was soon proposed, with additional energy and subtlety, from a new quarter.

It was Duncan who in 1973 (so she tells it) pulled from the bottom of a pile of job applications that belonging to one T. J. Clark, an almost unknown thirty-year-old Englishman who had just published two books devoted to the art of the 1848 Revolution and Gustave Courbet, The Absolute Bourgeois and Image of the People.4 The quality of the works and the confidence of the voice were undeniable, and Clark was quickly offered a position. His decision to leave England and come to the United States was undoubtedly the result of many factors, but the dire economic circumstances in Britain may have been one. The year 1974 saw the end of the almost three-decades-long expansion of the United States and European economies. From an average growth rate of 7.2 per cent during the previous two years, the US economy slid into a contraction of more than 2 per cent; the situation was even worse in England, where the decline was nearly 4 per cent. And unlike in the United Kingdom, hiring in the California system was largely unaffected by the downturn. (That the decline in both countries marked the beginning of a major contraction – phase B of a Kondratieff wave that still continues – was at the time unrecognized, except perhaps by Paul Sweezy, Immanuel Wallerstein, Ernest Mandel, Robert Brenner and a handful of other radical economists and historians.)5

Another factor in Clark’s defection may have been Los Angeles’ well-known, if not always congenial, left history. It was called ‘Weimar on the Pacific’ in the 1940s for its large population of German-speaking intellectuals, many of them communist, including Theodor W. Adorno, Max Horkheimer, Alfred Döblin, Arnold Schoenberg, Lion Feuchtwanger and Bertolt Brecht. The latter’s poem about the city, entitled ‘Contemplating Hell’, was no doubt familiar to Clark, but did not deter him. It begins:

Contemplating Hell, as I once heard it,

My brother Shelley found it to be a place

Much like the city of London. I,

Who do not live in London, but in Los Angeles,

Find, contemplating Hell, that it

Must be even more like Los Angeles.6

More significantly, Los Angeles was now becoming a magnet for New Left scholars, with posts taken by the young Marxist historians Brenner and Russell Jacoby. In addition, David Kunzle, the British social historian of art – in self-deprecation he would say ‘Marxisant’ – was a lecturer at the California Institute of the Arts in Valencia and the author in 1973 of The History of the Comic Strip, a genre that had always been beneath the radar of art historians more disposed to Ingres than Cruikshank. He was hired at UCLA in 1977.

Clark remained at UCLA for only a couple of years, but in that time became the teacher or advisor of several graduate students including Thomas Crow, Holly Clayson, Serge Guilbaut and Joan Weinstein, all of whom practised, at least for a time, some variant of radical or Marxist art history. They concerned themselves with the ways in which works of modern European or American art articulated divergent class and political interests; described artists as commodity producers rather than as geniuses outside of time; and understood art works as sites of contestation more than as expressions of social consensus. But each of them also succumbed, to a greater or lesser extent, to what Jacoby called a ‘fetish of the defeated’ – that is, a tendency not just to reject the autonomy of art as Werckmeister and Duncan had done, but to see revolutionary failure or defeat as preordained, and reification as inevitably triumphing over resistance regardless of the activation of the underlying social base. Guilbaut, for example, published in 1985 his How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art, arguing that Abstract Expressionism was hardly the radical voice its champions made it out to be, but rather a rhetoric of Cold War liberalism, barely distinguishable from the shrill cries of anti-communism.7 (Guilbaut’s error, ironically enough, was the vulgar Marxist one of assuming that he who pays the piper always calls the tune.) Weinstein, a student of Werckmeister, published in 1990 a book entitled The End of Expressionism, which argued that German state institutions, and the various pre-First World War vanguard movements, combined to turn Expressionism into a veritable language of revolution, only to see that association dissolve in the disastrous aftermath of the actual revolutionary upsurges in Berlin, Munich and elsewhere in 1918–19.8 In both books, avant-garde strategies are presented as hopelessly compromised, with collapse or accommodation inevitable. Crow, too, in the end accepted this undialectical parti pris, although in his first major publications he assumed a different posture, the result perhaps of his closer emulation of the theory and method adumbrated in Clark’s two early books.

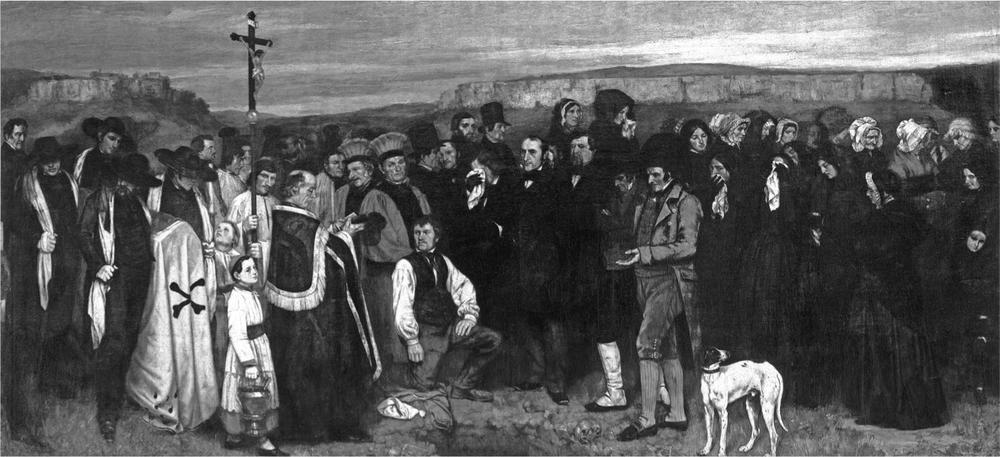

1 Gustave Courbet, A Burial at Ornans, 1849–50, oil on canvas, 315.2 × 660.4 cm. Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

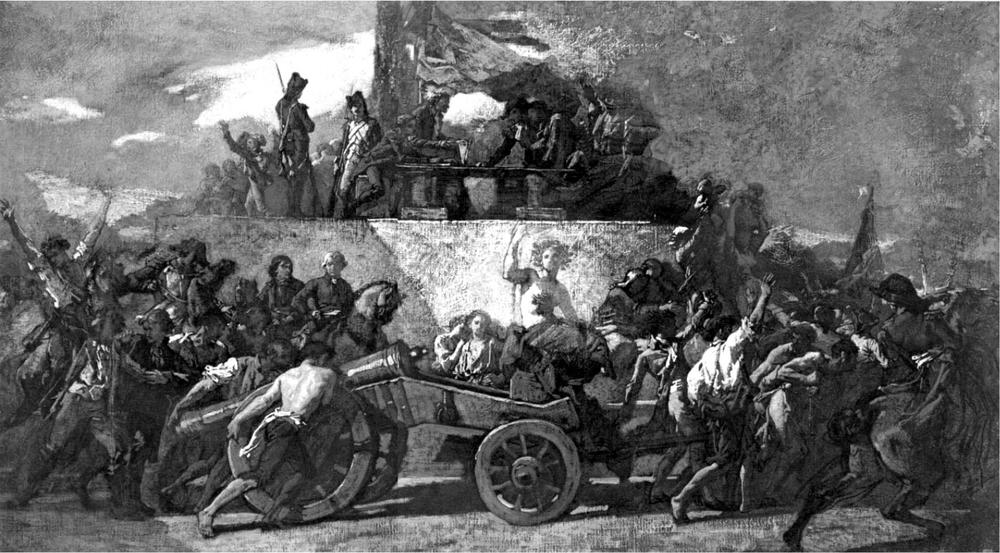

What characterized Clark’s work immediately before he came to UCLA was its recognition of the class-component of vision and its supple use of the Marxian concept of mediation. For example, he showed that Gustave Courbet, in his trilogy of works from 1849–50 – The Stonebreakers, A Burial at Ornans [1], and The Peasants of Flagey Returning from the Fair, marshalled a set of styles and techniques derived from popular art – for example, cheap woodcuts and broadsheets from Épinal [2] – for the purpose of putting history painting (that mode of high-mindedness, if not pomposity, that dominated the walls of the Salons) at the disposal of workers and peasants. The distinctive attributes of modernist painting therefore – such as its flatness and affectlessness – were not the consequence of some quasi-Kantian redefinition of the medium, but signs of affiliation with an entirely alternative and demotic artistic tradition. Clark demonstrated, as well, that while the success of that avant-garde gambit ultimately depended upon the mediating circumstances of viewership – economic, geographic, ideological and biographic – its outcome could not be forecast at the beginning. A Burial, as one of its contemporary antagonists wrote, was an ‘engine of revolution’, and Clark agreed, notwithstanding the Napoleonic coup d’état in December 1851 that left in tatters both the socialist cause and Courbet’s project of Realism. Some popular movements fail not because of the theoretical impoverishment of their leaders or, as Marx wrote, their ‘speaking and writing section, politicians and literati’, but because of the sheer strength of the forces of order. These were lessons no doubt learned from Clark’s own experience with the Situationist International, a circle of artists and revolutionaries who during the uprisings of May 1968 in Paris lent their efforts to organizing students and workers in a massive general strike that nearly brought down the French government of President Charles de Gaulle. Within weeks of de Gaulle’s dissolution of the National Assembly on 30 May 1968, however, revolutionary energies were dissipated, and the opportunity had passed for what the Situationsts called détournement – the diversion or reorientation of commodity culture for the purpose of enabling the free pursuit of primitive desires. But that defeat did not invalidate all of the political and aesthetic strategies that preceded it. These, anyway, are some conclusions that may be drawn from Clark’s writing and teaching of the early and mid-1970s, ones not fully absorbed by his UCLA students.

2 Anonymous, Le Convoi de Malborough, lithograph, Pellérin lithographers, Épinal, c. 1860.

Back in Albany, New York, the halcyon days of seemingly unlimited educational and arts spending were over, and the mood was grim. Three years before, Governor Rockefeller had overseen the brutal suppression of a prison uprising at Attica near Buffalo, leading to the deaths of thirty-nine prisoners and ten guards, and in 1973 he signed a series of anti-drug laws that mandated long prison terms for possession and sale of so-called narcotic drugs, regardless of the age or record of the offender. (The sale of two ounces of marijuana, opium, heroin or cocaine was punished with a minimum sentence of fifteen years to life.) ‘Law and Order’ – Nixon’s, Agnew’s and other Republicans’ racially inflected slogan – remained the byword in Albany as elsewhere in late 1973 and 1974, as Rockefeller resigned the governorship to become Gerald Ford’s appointed vice-president. The State University of New York was still the largest system of public higher education in the country, with over 230,000 students, and Albany remained one of its flagships (its campus designed in 1954–6 by Edward Durrell Stone), but now retrenchment was the order of the day. Ann Harris found her tenured position under threat, and at the end of 1974 left for greener pastures at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Robert Kinsman was summarily fired. Though there was a modest recovery underway by the time I graduated in 1977, and the unemployment rate had declined, the lure of a fellowship from the wealthy Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts, just thirty miles to the east, was irresistible.

1978: Albert Boime, Herbert Marcuse and Jimmy Carter

I received my initial graduate training in art history at Williams College between 1977 and 1979. There I studied with, among others, Julius Held, George Heard Hamilton, Daniel Robbins and Albert Boime. At Williams, Boime was visiting professor in 1978 and taught a seminar on the French juste milieu, the art that developed in the wake of the 1830 revolution and the regime of Louis Philippe. Thomas Couture – part Classicist and part Romanticist, part modernist and part pompier, part radical and part conservative – was the key figure in Boime’s course, and the subject of a massive monograph he published two years later. We spent a long time in that class looking at Romans of the Decadence and The Enrolment of the Volunteers of 1792 [3], the latter of which was housed in the nearby Springfield Museum of Fine Arts. Later that year, Boime took up his position at UCLA – he was hired by Werckmeister – and his seminar on juste milieu led me down a path that eventually intersected with that of Werckmeister, Clark, Crow and southern California’s radical intellectual tradition.

First, Boime was unapologetically Marxist. He would more or less repeat Karl Marx’s two least nuanced formulations of method that became the basis for what in the twentieth century was called ‘dialectical materialism’, or what Stalin called ‘Diamat’. The first is from The Communist Manifesto: ‘The history of all hitherto existing societies is the history of class struggle’; and the second, from the 1859 Critique of Political Economy: ‘The totality of the relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society, the real foundation, on which arises a legal and political superstructure, and to which correspond definite forms of consciousness.’ Though these statements still seem to me, in a general sense, true, they do not take us very far down the path of an art history that is both historical and material in outlook. Yes, the struggle between patrician and slave, peasant and lord, and proletarian and bourgeois has in successive ages shaped the disposition of power and distribution of resources, but this binary formulation denies the dynamic character of the contest: that each class is always in a process of transformation, and that subsidiary groupings – some of which are organized according to ethnic, gender, national or religious characteristics – may also be determining of the outcome of a given political dispute. And while it is also true, as Marx said, that the idealist Hegel must be stood on his feet, the materialist approach to history does not argue that the superstructure – philosophy, law, literature, art and culture in general – is merely a reflection of the economic foundation of a given society. Rather, as Marx himself realized, and as generations of scholars who followed him also understood, the two domains could not be so easily separated; culture or ideology, as Marx elsewhere wrote, ‘becomes a material force when it grips the masses’.9

3 Thomas Couture, The Enrolment of the Volunteers of 1792, 1848–51, oil on canvas. Museum of Fine Arts, Springfield, Massachusetts.

Without these two correctives, a radical art history would be impossible since the discipline is most of all concerned with understanding why works of art look the way they do and what they meant to their original audiences, questions that cannot possibly be answered except by examining the changing subsets of the large social formations that actually made, looked at, responded to and collected works of art. And we must also recognize that art works – at least at certain key moments in history – actually changed minds and moved bodies to act in the sphere of the political. (This, as we have seen, was one of Clark’s key insights concerning Courbet in 1850. It was also fundamental for his pupil Crow, whose dissertation was completed in 1978 and concerned the political impact of Jacques-Louis David’s Oath of the Horatii when it was exhibited at the Salon of 1785.) Moreover, the distinction between the economic foundation and the cultural superstructure is not always clear. Take, for example, the French Salon, the particular focus of Boime’s research before he came to UCLA: it was from the mid-eighteenth to the late nineteenth century at once a marketplace for a particular type of luxury good and an institution for the inculcation of ideology. Or take the many other arts and manufactures that exist on the border between base and superstructure and that clearly fall within the domain of art-historical research – Wedgewood, Thonet, Morris and Company, Liberty, the Bauhaus and even Andy Warhol’s Factory!

But back in 1978, my dissatisfaction with Boime’s teaching did not lay primarily in his conventional or ‘vulgar’ Marxism – I had read very little Marx up to that point – but in his almost complete dismissal of psychoanalysis. I spent my second summer in Williamstown reading the complete works of Sigmund Freud (I cannot now remember why, except that I had just finished reading Jane Austen) and, given the investment, I could not accept the idea that the Id, Ego and Superego, the Oedipus Complex, the Castration Complex, parapraxes, the Pleasure Principle, Thanatos and all the rest were mere superstructure and without any foundation in the actual matter and dynamics of the human mind and brain, or without any practical or historical significance. What I turned towards as the result of the challenge from Boime, therefore, was the work of Norman O. Brown and Herbert Marcuse. Brown’s two best-known works, Life Against Death (1959) and Love’s Body (1966), were efforts to achieve a synthesis of Marx and Freud, at the time the holy grail of left intellectuals. Capitalism itself, Brown argued, effected a colossal repression or group neurosis, a childlike anality marked by an extreme of possessiveness, acquisitiveness (what Marx in 1844 had called ‘the sense of having’), a preference for control and an infatuation with ‘filthy lucre’. What was needed, therefore, was a revolution of desire – a ‘polymorphous perversity’ that would be communal, erotic, expressive, anti-authoritarian and anti-establishment.

Marcuse, who like Brown taught in California in the early 1970s (the former at San Diego, the latter at Santa Cruz), argued by contrast, in One Dimensional Man (1964), that ‘technological rationality’ – the achievement of material wealth under the aegis of monopoly capitalism, combined with a high degree of personal freedom in the West (remember this was written at the apogee of the postwar economic expansion) – had effected not a widespread repression but a general ‘desublimation’, an emotional and bodily pleasure that had rarely if ever been so widely available.10 But far from being liberating, this desublimation was, in fact, ‘repressive’ since it blunted more profound drives for emancipation and the good life, and even blocked the very ‘polymorphous perversity’ that Brown had celebrated in his earlier Life Against Death.11 Art and literature themselves had succumbed to ‘repressive desublimation’, not so much because they were subsumed by kitsch, as Clement Greenberg had once argued, but because they were assimilated in a ‘harmonizing pluralism’ that permitted everything and was threatened by nothing. No longer did the arts function as ‘the Great Refusal – the protest against that which is’; instead ‘they were absorbed by what they refuted’, and functioned to entertain rather than challenge.12

I should note here that Marcuse’s views about art changed in the last decade or so of his life. When in La Jolla in 1975 he met with Werckmeister, Clark, Lee Baxandall, Bram Dijkstra and Fredric Jameson as part of a new (and short-lived) ‘California Group’, he was asserting the intellectual and political significance of an idealist ‘aesthetic dimension’ as a riposte to modern instrumental and technological rationality.13 Emancipated from its material base, Marcuse claimed, nineteenth- and twentieth-century art announced revolutionary change long before such change could actually occur in material reality. Werckmeister and Clark, as we have seen, and Jameson too, took an opposite tack to argue that what Marcuse called ‘cultural revolution’ was a chimera and that recent art had become ‘affirmative’, a handmaiden to, if not indistinguishable from, the culture industry, in effect using early Marcuse to argue against late Marcuse.

What Brown and Marcuse offered me in 1978 – a decade after they were taken up by the American New Left for their bracing anti-establishmentarianism and apparent hedonism – was an understanding that what we then called ‘high art’ was in constant struggle and negotiation with technological and capitalist development, and that in fact, the two domains could not be disaggregated. Moreover, I learned that the achievements of the previous decade – in the domains of civil rights, free speech, anti-war and arms control, women’s and gay liberation – were at best partial and provisional, and potentially repressive forms of desublimation. Indeed, the new social order proposed by Jimmy Carter – despite lip service paid to international human rights – consisted of little more than weak moral homilies and cultural pluralism tinged with asceticism, precisely the opposite of what Brown, Marcuse and the New Left championed. And, of course, within two years progress in all social and political domains would be rolled back with the anointing of Ronald Reagan. Major sectoral changes in the United States economy – the decline of the automobile and steel industries and growth of the service sector, disinvestment in national infrastructure, and the rapid rise of the London and New York financial services sector – all combined to destabilize and frighten the national electorate and render nugatory theories of revolution that had flourished in the 1960s.

But the art history of my time did not then seem crippled by the ‘harmonizing pluralism’ described by Marcuse. The work of Clark and a group of other young British Marxist and feminist scholars – including Adrian Rifkin, Lisa Tickner, Fred Orton and Griselda Pollock, who wrote for the new journal Art History and the magazine Block – suggested to me that there was an emerging model for art-historical work that might soon conquer the field. It entailed close and sustained attention to the style and structure of works of art in the confidence that it was precisely in their subtle formal interstices – and especially in anomalous or otherwise inexplicable elements (shades of Schapiro) – that the operations of a larger political and ideological dynamic could be most clearly seen and understood. The scholarship required careful archival as well as formal discriminations if a case were to be made for an art work’s particular critical salience, and radical art historians were, as a group, committed to making them, especially since the constant, disingenuous complaint of right-wing art history was that the left wing lacked ‘an eye’, the connoisseurial capacity that supposedly distinguished real from ersatz art historians. The result of this marriage of formal and archival attentiveness was a social history of art that at its best was true to objects and their changing histories and, as Thomas Crow recently wrote to me, provided ‘a deeper analysis of the ways of capital [than was otherwise available]’. In 1978 therefore, at the age of twenty-two, I believed that art historians might themselves revive an avant-garde impulse that was inoperative, if not defunct, in the current artistic and political spheres during the waning months of the 1970s, when Carter was walled up in the White House Rose Garden, Reagan lay waiting in the wings, and the American art scene – which I covered as a critic for Arts Magazine – was dominated by the affectation and empathy of the triad of Robert Longo, Julian Schnabel and David Salle.

1984: Art History in the Age of Reagan

In 1984 I completed at Princeton my dissertation on Odilon Redon under the guidance of Thomas Crow, and travelled out to Los Angeles to begin teaching at Occidental College, while Werckmeister soon thereafter left UCLA and moved to Northwestern, where he and I would eventually become colleagues. At almost the same time, Crow was denied tenure despite having published what was widely considered the most important book ever written on David and the art of the French Revolution. The antagonism of East Coast art history towards the West Coast insurgents was manifest at Harvard as well as Princeton, where Clark (hired by Harvard in 1981) faced attacks from his senior colleague Sidney Freedberg and from Irving Lavin at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. But then suddenly a peculiar thing happened: the old guard modernists folded and the social art historians (or at least a subset of them) prevailed, but in their victory left behind some of the very insurgent energies that were their initial impetus. That the old boys packed it in – the Eitners, Elsens, Champas, Ackermans, Jansons, Dorras, Hamiltons and Rosenblums – is not surprising: they were approaching retirement and had accomplished surprisingly little. Most of their work was pre-art historical: collecting and cataloguing images, identifying subjects and sources, addressing changes in style, and sometimes examining patronage – but avoiding serious analysis and interpretation. When the work was more ambitious, as in the case of Rosenblum, it was ahistorical and untheorized: a matter of reflection theory and zeitgeist. 14

Crow’s work – on David and other subjects – was obviously more ambitious, and clearly revealed his Californian upbringing, experience and training. In an article entitled ‘Modernism and Mass Culture in the Visual Arts’, he theorized and historicized the relationship between the two, using Impressionism as the pivot. Impressionism, he said, revealed a complicity between modernism and commodity culture that previous critics – notably Greenberg – were at pains to deny. Quoting at length from Schapiro’s 1937 essay ‘The Nature of Abstract Art’, Crow noted that the art of Claude Monet, Auguste Renoir and the rest depicted (this is Schapiro via Crow):

breakfasts, picnics, promenades, boating trips, holidays and vacation travel. These urban idylls not only present the objective forms of bourgeois recreation in the 1860s and 1870s; they also reflect in the very choice of subjects and in the new aesthetic devices the conception of art solely as a field of freedom for an enlightened bourgeois detached from the official beliefs of his class. In enjoying realistic pictures of his surroundings as a spectacle of traffic and changing atmospheres, the cultivated rentier was experiencing in its phenomenal aspect that mobility of the environment, the market and of industry to which he owed his income and his freedom.15

But rather than conclude from this, as had Schapiro, that the Impressionist painter simply ‘succumbed to the general division of labor as a full-time leisure specialist’, he proposed that the very relentlessness with which these artists went about their pursuit of leisure – at the levels of both subject and style – revealed a coordinated group effort to rescue some kind of rich and affective communal life from the damaged goods of provisioned recreation and commodity culture – the bread and circuses of late Second Empire and early Third Republic France. In this respect, the Impressionists more resembled subsequent resistant subcultures – think Beats, Mods, Skinheads, Punks, Hip Hop – than previous artistic schools and movements. Such resistant subcultures employ style in its widest sense – hair and clothing, patterns of speech, drug use, and modes of recreation and representation – to establish imagined relations to arenas of life and labour that are cut off to them by virtue of their class or race. In making this argument, Crow obviously reached outside art history to anthropology and sociology, in particular to the English theorists Phil Cohen and Stuart Hall from the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies at Birmingham University, as well as the latter’s protégé Dick Hebdige. (He may also have been drawing upon his knowledge and recollection of southern California’s rich history of subcultural styles, from zoot suit and low-rider in the 1940s to waacking and hardcore in the 1970s.)

And later modernist artists too – from Picasso and Braque to Andy Warhol and beyond – similarly immersed themselves in the detritus, ephemera and erotic blandishments of mass and commodity culture in order to create an alternative social and symbolic space that might be more satisfying and arresting than the ones in which they found themselves. In this way, modernism may be seen as parasitical upon mass culture. But the energy extends in the opposite direction as well: precisely because of their extremism and intensity, and their constant prowling for new experiences and sensations, the modernist avant-garde revealed to the wider capitalist culture areas of expressive deficit, that is, modes of experience and affective intensity that had not yet been fully colonized and exploited by capitalist culture, or what Theodor Adorno called ‘the Culture Industry’. In Crow’s now well-known formulation, ‘the avant-garde serves as a kind of research and development arm of the culture industry’.16

That final, jaundiced conclusion – which has been enormously influential for subsequent work on modernism and the avant-garde – does not seem to me quite right. To my view, the history of the European and American avant-garde – taking account of its diffusion to Latin America, Africa, India and elsewhere – indicates that some art works possess a cognitive force whose effect can be either immediate or delayed, proximate or remote, but in any case material and political, and that the consequences of an aesthetic intervention cannot be forecast at the outset. In their first major works, Clark and Crow argued this, but their writings of the early and mid-1980s bear the stamp and tenor of their time: California in the age of Reagan. It was a period of particular despair for the left – a president and former movie actor, whose warmongering was only matched by his insouciance – held a country in his thrall by means of an extraordinarily well-managed media apparatus. Why wouldn’t critics and art historians assume that mass culture and ‘the spectacle’ – that synonym for reification coined by the Situationist Guy Debord – were capable of overwhelming all challenges, indeed able to subsume and utilize all resistance. Why wouldn’t they argue, as Werckmeister had in 1973, that ‘cultural revolution’ was a meaningless term in the absence of a fully fledged social and political revolt? ‘There is no alternative’ intoned Margaret Thatcher on a regular basis during those depressing years, meaning that free markets and globalization, organized and orchestrated by the principal capitalist powers of the northern hemisphere, must inevitably have their way. The power of Hollywood and Disney – or ‘the Industry’ as everyone calls it in Los Angeles – seemed equally certain in those years.

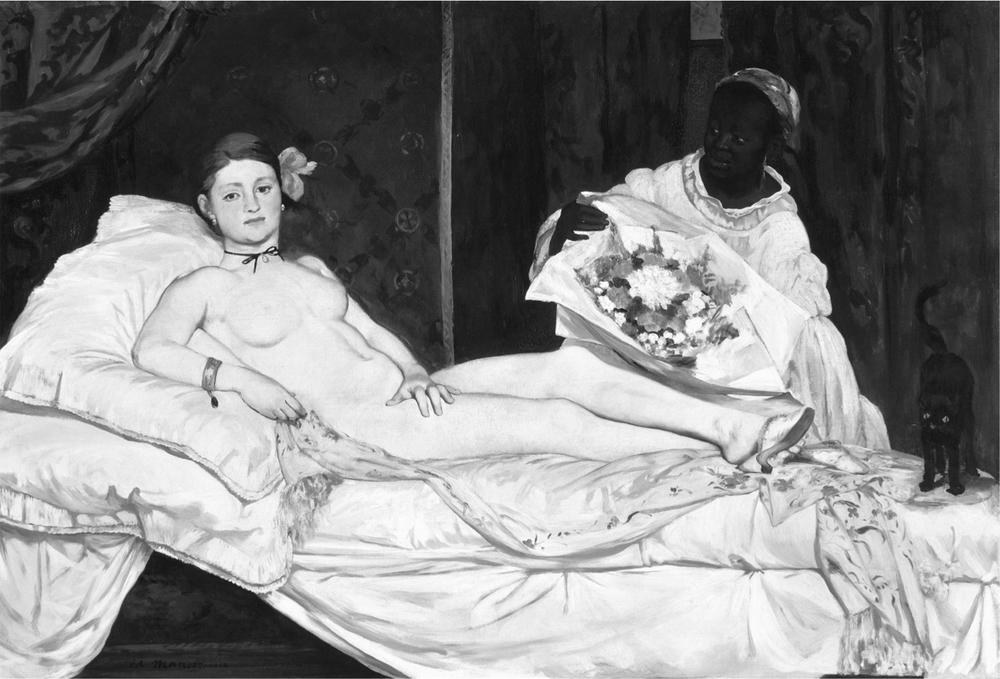

Thus it appeared to many that the circuit between art and capital was closed, and the possibility that the avant-garde may actually intervene into the circuitry of real life was ended, if it ever existed. In the 1980s and after, Clark too seemed convinced that the historic avant-garde was a myth. After pages of careful attention to the form of Manet’s Olympia [4] in the chapter devoted to it in The Painting of Modern Life (1985) – its location in the tradition of the nude, and analysis of the voluminous and often shrill critical response to it – Clark concludes that the work was at once particular and general, multivocal and singular: ‘The achievement of Olympia, I should say, is that it gives its female subject a particular sexuality as opposed to a general one. And that particularity derives, I think, not from there being an order to the body on the bed but from there being too many, and none of them established as the dominant one. The signs of sex are present in plenty, but they fail, as it were, to add up.’17 Opacity and negation, Clark argued, are the best that modernists can hope for.

4 Édouard Manet, Olympia, 1863, oil on canvas, 130.5 cm × 190 cm. Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

Conclusion: Counter-intution

I will be brief. Southern California, and in particular UCLA was the birthplace of a version of radical art history that was deeply influential. It was the product of two distinct European intellectual and political traditions, as well as southern California’s peculiar culture and history. The Frankfurt School theorists Adorno, Walter Benjamin, Leo Lowenthal (who taught at Berkeley from 1956 to 1972) and, of course, Marcuse had a significant impact on radical or critical art history. Werckmeister, Brenner and Jacoby at UCLA, Jameson at the University of California, San Diego, and Martin Jay at Berkeley were all instrumental in transmitting and clarifying this intellectual legacy. The Situationist tradition too – though rarely invoked explicitly by Clark during his brief spell at UCLA – was also significant, especially since it offered so many useful terms for analysing the highly mediated culture and industry of southern California.

5 Internal FBI memo concerning ‘Black Nationalist Hate Groups’, 6 May 1970.

But what is surprising or counterintuitive here is that radical art history did not arise – as might be expected – from a robust movement for social change, but from a world-historical political defeat. By 1971, when Werckmeister became chair at UCLA, the anti-war and civil rights struggles that marked campus politics in the 1960s were mostly over. The FBI’s Counterintelligence Programs [5] had successfully infiltrated the Los Angeles Black Panther Party and instigated fratricidal warfare, and the struggles of Chicano and Asian students and community leaders for equal rights and opportunities settled into demands for so many ethnic and cultural studies programmes. This was the period of what Jameson called ‘the cultural turn’ and the idea of a radical art history – one that was fully adequate to objects and histories, while providing ‘a deeper analysis of the ways of capital [than was otherwise available]’ – was buffeted by enormous assimilative forces. In the face of these forces, radical art history blinked, accepting either what was taken (mistakenly) to be the Situationist orthodoxy that resistance to the power of the spectacle is futile, or the Marxist orthodoxy that revolutions in culture are phantasmatic in the absence of political revolution.

But alternative perspectives still exist and remain to be fully explored. (1) That art is one of many expressive systems that have at times in the past gripped the masses and become a material force, and that even when their power is cognitive more than instrumental, they may aid in the restructuring of consciousness as to once again merit the designation materialist and political. (2) That however great the recuperative power of the avant-garde, its function in highlighting the affective deficits generated by capital may be even greater. Today increased diagnoses of depression and the massive dispensation of both psychotropic drugs and cognitive behavioural therapy indicate that the happiness gap – the space between the capitalist promise of pleasure and its deliverance – is continuing to grow in much of the economically most dominant powers. ‘Depressive hedonia’ is Mark Fisher’s pithy diagnosis of the antic search for pleasure and its constant retreat; it is a disease that grows more acute as the economic crises lasts longer.18 (3) That the authority of contingency must be better recognized – that the results of a particular ideological and cultural struggle cannot be determined before it has even been waged, and that success is always a possibility. This, anyway, was an intuition some of my generation had in the mid-1970s as we witnessed the defeat of the United States in Vietnam, the overthrow of Richard Nixon, and the succession of victories by the aging Muhammad Ali. It is one that we should keep in mind as we watch, or participate in, present or future Springs, Occupations, Awakenings and other social movements in the Middle East, United States, Europe and beyond.

1 Meyer Schapiro, ‘The Apples of Cezanne: An Essay on the Meaning of Still Life’, in Modern Art: 19th and 20th Centuries (George Braziller: New York, 1978), p. 12.

2 Carol Duncan, ‘Virility and Domination in Twentieth-Century Vanguard Painting’, Artforum, vol. 12, no. 4 (December 1973), p. 31.

3 Otto Karl Werckmeister, ‘Marx on Ideology and Art’, New Literary History, vol. 4, no. 3 (Spring 1973), p. 508.

4 T. J. Clark, The Absolute Bourgeois: Artists and Politics in France 1848–1851 (Thames & Hudson: London, 1973) and Image of the People: Gustave Courbet and the 1848 Revolution (Thames & Hudson: London, 1973).

5 See, for example, ‘The Depression: A Long-Term View’, MR Zine, 10 October 2008, <http://www.monthlyreview.org/mrzine/wallerstein161008.html>, accessed 25 August 2013.

6 Erhard Bahr, Weimar on the Pacific: German Exile Culture in Los Angeles and the Crisis of Modernism (University of California Press: Berkeley and Los Angeles, 2007).

7 Serge Guilbaut, How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art: Abstract Expressionism, Freedom, and the Cold War (University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 1985).

8 Joan Weinstein, The End of Expressionism: Art and the November Revolution in Germany, 1918–19 (University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 1990).

9 Karl Marx, ‘Introduction’, Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right (1844), <http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1844/df-jahrbucher/law-abs.htm>, accessed 25 August 2013.

10 Herbert Marcuse, One Dimensional Man: Studies in the Ideology of Advanced, Industrial Society (Beacon: Boston, 1964), passim.

11 Norman O. Brown, Life Against Death: The Psychoanalytical Meaning of History (Wesleyan University Press: Middletown, 1959), passim.

12 Ibid.

13 Marcuse, One Dimensional Man, op. cit.

14 See for example, Robert Rosenblum, Modern Painting and the Northern Romantic Tradition: Friedrich to Rothko (Harper and Row: New York, 1977).

15 Thomas Crow, ‘Modernism and Mass Culture in the Visual Arts’, in Modern Art in the Common Culture (Yale University Press: New Haven and London,

1998), p. 12.

16 Ibid., p. 35.

17 T. J. Clark ‘Olympia’s Choice’, The Painting of Modern Life: Paris in the Art of Manet and his Followers (Princeton University Press: Princeton, 1999), p. 131.

18 Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realist: Is There No Alternative? (O Books: Winchester and Washington, DC, 2009), p. 21.