AN ‘EVER-RECURRING CONTROVERSY’

JOHN THOMPSON, WILLIAM JAMES STILLMAN AND THE BOOTBLACKS1

John Thompson’s photographs, originally published in monthly parts through 1877 and 1878 as Street Life in London, have long had a place in the history of photography, but an uncertain one. The Crawlers or ‘Hookey Alf’ of Whitechapel have often been reproduced, while frequently being confined to the dismal category of proto-documentary, which establishes an unproblematic teleology between the nineteenth-century document and its later inflections. As the publisher’s note to the 1994 reprint of Street Life in London puts it: ‘John Thompson was a pioneering documentary photographer – one of a breed for whom arduous travel under extremely difficult conditions did little to dampen enthusiasm.’2 None of this tells us much. While the first historians of photography – Beaumont Newhall, Helmut Gernsheim, Walter Benjamin, Gisèle Freund and Lucia Moholy – took up a range of photographic forms in search of a ‘new vision’, those who followed tended to narrow their focus to constitute the history of photography on the grounds of the museum and its approved forms of taste. Documents, in contrast, belonged in institutional archives and reports of both official and non-governmental organizations.

During the 1980s, a group of theorists and historians began to pay attention to the photographic document and its role in culture. Molly Nesbit’s account of Eugène Atget and the document is for me the outstanding description and definition, and I hope to develop on her categories in this essay.3 Nesbit approaches the document as a form through the work of Atget, who, she suggests, made and sold photographs for a variety of clients. In particular, he supplied pictures to workers in the skilled Parisian trades: decorative-metal workers, illustrators, theatre designers and people who traded on nostalgia for ‘vieux Paris’. Atget was not an artist and he did not claim anything special for these images. Art was of little significance for the craft workers or designers who employed these pictures. In this sense, Nesbit characterizes the photo-document as a ‘nonaesthetic’, workaday form. Atget’s documents, she argues, displayed two principal features: first, they were practical, utilitarian images; second, they were built on semiotic polysemy or ‘openness’. Usually, they were frontal and planar, but documents have no absolute form: the same image might be used by different specialists, and so it had to be available to different kinds of specialist attention. Information, clarity and detail are what matter in such images. According to Nesbit, ‘an architectural photograph would be called a document, as would a chronophotograph, a police i.d., or an X ray. They had one thing in common: all of them were pictures that went to work.’4 However, before considering how the document figured in nineteenth-century debates, I want to comment on one of the main lines of the research from the 1980s, which drew heavily on Foucault’s account of ‘carceral society’. As we know, for many anglophone readers and writers, this work seemed to offer an alternative to Marxism, dissolving class politics and the state into an amorphous power.5 The account, first advanced by John Tagg and subsequently adopted by David Green and others, suggested that these photographs represented a crucial point at which the camera extended the disciplinary gaze of the Panoptican out onto the streets.6 Tagg argued that Thompson’s work, along with that of Thomas Annan, Dr Hugh Diamond, Arthur J. Mumby and others, entailed ‘a “procedure of objectification and subjection”, the transmission of power in the synaptic space of the camera’.7 During the second half of the nineteenth century, it was said, photography became a pervasive technology of power-knowledge that cast its web over society. Foucault was concerned with an institutional or professional ‘normalizing gaze, a form of surveillance that makes it possible to qualify, to classify and to punish. It establishes over individuals a visibility through which one differentiates them and judges them.’8 In the ‘regimes of truth’ that emerged from this process, visibility was particularly important. Subjecting the bodies of the poor, the outcast and the marginal to disciplinary visibility, these theorists insisted, photography played an important role in constructing discourses of ‘otherness’. Visibility exposed the objects of knowledge to controlling scrutiny. It was by defining and demarcating the ‘deviant’ that a normative conception of the self could be established: the ‘abnormal’ or ‘deviant’ defined what it was to be normal. This process of investigation entailed a hierarchical vision, because in each case the person with the camera had the social authority, or money, to arrange and pose others for scrutiny: Thompson, for instance, noted the ‘trifling sums’ that he paid to poor Chinese people for ‘the privilege of taking such subjects’.9 Some people were authorized to look; others were subject to what Tagg called the ‘burden’ of being the ‘bearers of meaning’.10 There is reason enough to locate Street Life in this context. As a reviewer in the Graphic put it: ‘The manifold industries of the poor in our great city are transferred from the street to the drawing-room by “Street Life in London”.’11 Whose street? Whose drawing-room? Another writer suggested: ‘If, henceforth, there should continue to be truth in the proverb that “there is a half of the world which knows not how the other half lives,” it will not be the fault of Mr. Thompson, or his literary coadjutor, Mr. Smith.’12 Similar comments are to be found in the Leeds Mercury, Northern Echo, Morning Post and a host of others; they demarcate ‘us’ from ‘them’. The account of photography that emerged in the 1980s re-evaluated these images, positioning them at the centre of photography and assigning them a determining social weight.

Of course, this is to go over old ground and the debate has moved on. For one thing, we know there is much more to Foucault than this story allows.13 Nevertheless, the attention to Thompson and his ilk appears to have been short-lived. The kind of images that drew so much attention during the 1980s are again slipping from view as a younger generation, shaped by the experience of neoliberalism and postmodern theory, have turned away from power, ideology and documents. In their place, we find a new engagement with auteurism, playfulness and self-reflexivity. The current obsession with Roland Barthes’s Camera Lucida and Michael Fried’s photographic turn are just surface ripples of a deeper current.14 In recent historiography, the document as evidential mode has been replaced by a few key areas of investigation that bear on the nineteenth century. First, there is an exploration of the pioneers of photography (principally William Henry Fox Talbot) perceived through the lens of postmodern theory; second, there is a growing body of work concerned with photographs by women – Julia Margaret Cameron, Clementina Hawarden and those elite amateurs that created elaborately decorated picture albums; third, in line with revisionist histories of an anti-modernist stripe that find complex effects in academic art, there is attention to the elite makers such as Camille Silvy. Whether it is Talbot, Cameron or Silvy, the photographer is positioned as a self-conscious picture-maker whose work can be mined for art-historical allusions and references, and the likes of Thompson are once again occluded. These readings are heavily influenced by the art of the 1980s and the art history that has spiralled out of it, but they often seem impervious to the wider emplotment of their work: if we put aside the veneer of theory and feminism, we find ourselves not so far from Mike Weaver’s ‘Talbot’ or Helmut Gernsheim’s ‘Cameron’.15 Canon critique has given way to a revivified aestheticism-cum-Victorianism, and the document again finds itself in the role of poor relation. My question is what are we to make of pictures such as those produced by Thompson? What kind of knowledge do we require to think about these images; to imagine their appearance and disappearance from the histories of photography?

There is a wider pattern of continuity across these historiographical shifts, which involves the ‘retreat from class’.16 The problem is that without the dialectics of capital and class – the critique of political economy – it is not really possible to come to terms with Thompson’s work or with the character of the document, and I do not just mean the content or subject of the images.17 These are images of the casual poor, but there is more to the matter than that. Thompson’s street figures will be familiar to any reader of Henry Mayhew and the emerging literature of social exploration, but one of them [1] strikes me as particularly symptomatic.18 This untitled picture appeared along with the photograph of ‘the donkey boy’ as illustrations to the section of Street Life entitled ‘Clapham Common Industries’. The presence of this image suggests some awkward questions about the social position of the photographer at this time. The accompanying text by the journalist Adolphe Smith – who was to become a labour and union activist – brings out the marginal status of the photographer. The success of such itinerant photographers, Smith argued, depended more on their manners than on skill. He wrote:

Many practiced hands, who have highly distinguished themselves in the studio, when the work is brought to them, are altogether unable to earn a living when they take their stand in the open air. They have not the necessary impudence to accost all who pass by, they have no tact or diplomacy, they are unable to modify the style of language to suit the individual they happen to meet, and they rarely induce any one to submit to the painful ordeal of having a portrait taken. On the other hand, men who are far less skilled in the art often obtain extensive custom by the sheer force of persuasion.19

According to Smith, many of the itinerants who worked Clapham Common had come down in life. They had, he said, previously: ‘been tradesmen, or owned their own studios in town; but after misfortune in business or reckless dissipations, they were reduced to their present less expensive and more humble avocation’.20 In the off-season, Smith argued, these men made portraits at the racetracks: often ‘being locked up by the police under the Vagrancy Act’, or ‘sleeping in a tap-room’.21 The character in the photograph, Smith claimed, is represented ‘with the class of subject which generally proves most profitable. Nurses with babies and perambulators are easily lured within the charmed focus of the camera.’22 This is a tale of class and gender, seduction and gullibility and there is much to be said. However, historians of photography seem to be drawn to Silvy’s gentlefolk rather than to nurses, babies and common photographers.

We do not need to rely on Smith’s text for our sense of the dubious nature of this practice; it is also figured by Thompson’s illustration. Thompson goes out of his way to include in our field of view all those questionable features that the photographer he depicted would have carefully excluded from his portrait of baby. Look at the mean handcart rigged up as a portable developing tent; the simple display of his wares that are hopelessly out of date; the empty, plain chair, the nurse and above all the presence of the two other men. The man behind the nurse, who is dressed roughly, is, I presume, the photographer’s assistant or ‘tout’. The young man, lurking in the shadow behind the tree, with what I take to be a basket, seems to be a decisive detail; he introduces a brooding and sinister presence into the frame. All this seems significant because it mirrors just what Thompson was himself doing; travelling the streets making photographs. Thompson, who was born in Edinburgh, spent most of the 1860s travelling and working in Asia: the Himalayas, Siam, Vietnam, Cambodia, Hong Kong and China.23 The albums and books he produced reveal a simultaneous attraction and repulsion to his subjects.24 In what was to become a cultural pattern, Thompson turned to photographing the English poor as something of an outsider.25

1 John Thompson, ‘Clapham Common Industries’, from Street Life in London, 1877/8. Library of the London School of Economics and Political Science, R(SR)/1146.

There is a distance between Thompson and the Clapham Common photographer, but it is not clear-cut or decisive. Audrey Linkman has suggested there was a critical reorientation of perceptions of this kind of work during the 1860s.26 Previously itinerant photographers had been viewed as pioneers, and their work was viewed as a decent or legitimate trade, but during this period they were repositioned by the photographic gentlemen as ‘travelling bunglers’ who undermined the status of the profession. These photographers made cheap portraits – sometimes for as little as sixpence – often they worked in old or cheap formats; the daguerreotype and the tintype were more common in this field than paper prints. These men were also prone to the odd dodge. The photographic gents were concerned with the way such men would tarnish their precious status; they seemed too proximate to the world of the huckster, showman or street musician. These figures congregated at sites of popular amusement, such as fairs, parks, seaside spots, race meetings and even pubs. Thompson’s photographer mentions these rounds of work, and it will be remembered Smith refers to ‘race meetings’, ‘tap rooms’ and ‘vagrancy’. As Linkman correctly observes, this was an area linked in the popular imagination with ‘cheapjacks and tricksters, operating in the twilight zone of petty criminality beyond the pale of respectability’.27 The inclusion of this image in Street Life casts its shadow over all the others, and suggests that we are not looking at the secure gaze of power, but at an unstable point of view. From this perspective, the photographer appears to belong – along with other street traders such as purveyors of ‘old clothes’ and patent medicine men – in a marginal and economically precarious circle of occupations. One batch of images in Street Life in London focuses on cabmen, another on assorted labourers, and there are miscellaneous traders, but it is worth noting just how many of the pictures take as their subject forms of artistic labour – admittedly in its low modality. There are, in addition to Clapham Common photographers, ‘“Caney” the Clown’ and ‘Italian Street Musicians’; there is a portrait of ‘Tickets’, a sign painter, and ‘The Wall Worker’ who hangs advertisements on a fence. Yet another group focuses on aesthetic pleasure: ‘Covent Garden Flower Women’; ‘Street Advertising’; the ‘Dealer in fancy-Ware’, ‘November Effigies’ and that walking picture ‘The London Boardman’. By extension, it is possible to recognize that many of the traders selected bear on bodily pleasure and taste: as well as the cheap fish seller, there are ‘Half-Penny Ices’, ‘The Street Fruit Trade’, ‘“Mush-fakers” and Ginger Beer Makers’ and ‘The Seller of Shell-Fish’. The point is that Street Life in London seems, if not internal to all of this, at least proximate to it. Photographers and reporters also walked the streets plying their trade. Thompson and Smith glimpsed a connection and traced a line that put together street life and the sensations.

There is a historiographical problem here. It seems to me that once you cut away conceptions of class and ideology from the analysis of images like this they can only appear as objects of aesthetic irony – that is to say, the moments of social anxiety, self-recognition or imbrication will be misrecognized as the defining tropes of modernist or postmodernist art. Discourse analysis dislocated from social interests means social unease can be recast as a formal mise en abyme of representation. The current obsession with the photo-document in conceptual art is symptomatic of this structure of feeling, because it turns on an ironized conception of the evidential mode. The fixation on ‘photo-conceptualism’ reveals a period disdain for those naive enough to actually believe in truth or reality.28 My point is that, in the condition of the long 1980s, the rejection of photography as a fine art generated its aestheticist antipode. But to make sense of this anxiety we need to think about the relation between documents and pictures revolving around patterns of social division and framed by, or set against, the intense debate on the labouring poor during the period.29 To be clear, I do not think Street Life in London engages in aesthetic irony or self-reflexive artfulness. Rather, it is a book redolent with petty-bourgeois doubts (and perhaps fears). The relation of self and other is much more immanent in Thompson’s work than that allowed for in the existing account. The respectability of photography is the key point in this instance, but it ran through everything photographers did during this period; they were profoundly insecure and the press repeatedly reinforced their association with the city’s low life and rabble. Some photographers wanted to force a clear distinction and insist on their own place in the circle of respectable professions, but what is compelling about Thompson and Smith’s book is that they seem to have worked through both proximity and distance, attraction and repulsion, as if they were not quite sure whether they were internal or external to the precarious forms of life they depicted.

Art works and documents were torn halves of photography in the period, and they have been further prised apart in recent scholarship. Photographers wrote endlessly about art, and their discussions constantly turn on the relation to an underling, usually figured as slave, servant or mechanic. The relation of art works and humble documents is embedded in a distinction between mental and manual labour and the concomitant oppositions between abstraction or generalization and particularity or detail.30 What we need to account for this problem is an oxymoronic construction – an art history from below. Here I am just going to look at one debate from the 1870s, initiated by W. J. Stillman, before returning once more to Thompson. In some ways this was the last great English debate on the character of photography before the rise of Pictorialism.

William James Stillman was an antiquarian and amateur photographer active in the Hellenistic Society. In February 1872, he published an essay that initiated an extensive controversy. If we include his replies, Stillman’s argument elicited some thirty contributions. On at least three occasions, the editor of the Photographic News – the journal in which the debate took place – tried to call a halt to the discussion, but he found it impossible to hold back the flood of invective. Stillman’s argument occasioned initial responses from H. P. Robinson and N. K. Cherrill, since they were directly implicated in his argument, but other leading photographer-writers were also drawn in to the discussion. W. T. Bovey, George Croughton, William England and Edwin Cocking all had their say. As the editor of the Photographic News put it, this was an ‘ever-recurring controversy’.31 The arguments are repetitive, but this kind of reiteration points to a knot or sticking point that registers a symptom or what we might call, shifting gear, a ‘structure of feeling’.32 The discussion might appear tedious to the reader, but it animated its participants. At various points, Stillman re-entered the fray. The military metaphors – and they are ubiquitous – are apposite and register that photographers saw themselves under attack. It is an example of the hypertropic flood of figurative language that broke out whenever anyone broached the question of photography’s status, and it provides access to key undercurrents of photographic ideology.33

Stillman was a fascinating figure: an American journalist, diplomat, art critic and painter who spent most of his life in Italy, Greece, Crete and England. A friend of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Louis Agassiz and others, he was a key figure in the acclaimed Adirondack Club. Sometime revolutionary conspirator associated with Lajos Kossuth in Hungary and Francesco Crispi in Milan, he proved unfit to fight in the Union Army during the American Civil War and instead became US consul to Rome and Crete. He edited the first American art journal, the Crayon, was for a while editor of Scribner’s Magazine, and then became a journalist for The Times; he wrote on the Cretan Insurrection and the revolution in Herzegovina. Stillman was not an artistic naïf: he was himself a painter and was close to Ruskin and Rosetti (Ruskin was godfather to his son). For what it is worth, he has been called ‘the first American pre-Raphaelite painter’.34 In 1870, he published The Acropolis of Athens, Illustrated Picturesquely and Architecturally in Photography.35 He also published a handbook for photographers and made technical improvements to apparatus. Leading photographic publishers sold his albumen prints, and his work is to be found in the archives of Alma-Tadema and others.36 Stillman could not be ignored by the gentleman guardians of photography.

The published responses to Stillman insisted that photography was a fine art, and I have argued elsewhere that by this time their sense of self was wrapped up with this idea,37 but attending to the dispute, which sometimes became very bad tempered, provides us with a way into the photographic imaginary around the time Thompson was working. One commentator signing himself ‘an indignant photographer’ claimed that they had ‘an enemy in our camp’. He referred to the ‘heresies’ that Stillman’s had set out ‘in all their naked hideousness’. Stillman, this writer said, ‘depreciated photography’ and was determined to ‘sink it in the estimation of its admirers as a mechanical trade’.38 What had Stillman done to deserve being afflicted with this set of mixed metaphors?

The answer is that Stillman had committed the primal sin when he wrote in the Year-book of the Photographic News for 1872 that photography was not a fine art but a record of fact; it rendered ‘what the eye may see, but no hand be it ever so skillful, render in perfection’. Photography was a ‘handmaid of the knowledge of the visible world’.39 Taking as his example Robinson and Cherrill’s In the Gloaming, he suggested this picture was a ‘mis-statement made by a combination of truth’.40 It should be remembered that Robinson’s book on Pictorial Composition had recently appeared.41 In this account, artistic beauty sits alone and apart, while handmaids and facts keep company. Immediately, the dispute began. A writer using the pseudonym of Theophilus Thiddlemitch described these views as ‘utterly heterodox and heretical’ and they could not be allowed to pass.42 This already suggests a consensus had descended with the gloaming over photography during the 1860s. ‘Thiddlemitch’ responded to Stillman’s suggestion that photographs were records of fact by suggesting that such pictures were: ‘dry, uninteresting, hopelessly uninstructive, very “primeval forests” of useless information’. What is being said here is that documents were primitive, shapeless or unformed and unselective – according to ‘Thiddlemitch’, this was a ‘tremendous mistake’ – what was needed he thought were not copies and records but ‘art’.43 Stillman responded that he had not ridiculed In the Gloaming; in fact, he thought it was excellent, if a work of artifice. Still, he ‘stood by his guns’. What makes art, he said, is not what is taken from nature, but the ‘poetic regard – a charm of memory, or an intensifying of some meaning which he found in nature’. Art entailed ‘idealization’, ‘greater unity and harmony’ and in this ‘photography must inevitably plead destitution’.44 There is a basic dichotomy in Stillman’s account – and it is one shared by his opponents – framed in the terms of academic aesthetics. While he was much more careful than many critics in formulating his terms, he was suggesting that art results from the idealization of nature; in contrast, photography is an accurate record or copy of existing phenomena. Art and photography, he said, were ‘antipodal’. He claimed that ‘substantially and materially, photographs are records of nature’ and not amenable to what the photographer thought about the subject.45 The imagination was central to art and the document or record was the form of image which had not been marked by imagination or subjective presence. An important line demarcated photography from art, and documents from pictures.

In a published response, Robinson and Cherrill begin in military frame noting that Stillman ‘has let off his guns, but the shot did not come our way particularly’. They insisted that photography was amenable to ‘artistic feeling’ and was more than a ‘mere map-making copy of the mechanical camera’. While Stillman admitted that the work of Robinson and Cherrill displayed ‘harmony and unity’ and could not be dismissed as mere mechanical reproduction, he insisted that ‘photography is not an art in the sense of the term which we imply when we talk of its higher meaning’. Robinson and Cherrill conceded this point, but attempted to hold back the full force of Stillman’s argument and sustain a link between art and idealization.46 Stillman’s response suggested (citing the Journal of Arts and Sciences) that there many arts that ‘manifest great technical excellence’, such as glass polishing, and then continued ‘a clever and dexterous boot black [is] an artist in his way’.47 Here Stillman put his foot in it, by contrasting an art of ‘technical achievement’ such as bootblacking – the cleaning of shoes done on the street, often by the very poor – and an art of design in a way that lined photography up with the manual work. And then he offered another analogy that was bound to rankle. He wrote:

There is a turning of a lathe which will, if you place a model of a statue in one compartment turn you out a perfect copy in another. Suppose the model to be a living figure and the copy to be a statue, would the mechanist, no matter what his part in the arrangement of the figure be a sculptor?48

By the beginning of the 1870s, the term ‘mechanical’ had become slippery and could refer to mechanics (workers) or machines and sometimes confounded the two. Turning the handle in this dispute clearly refers to machine work, but it echoes with the constant references in the photographic literature to street musicians working with a barrel-organ as a simulacrum of artistic labour.49 Like barrel-organ players, the effect seemed artistic, but it was utterly mechanical and mindless. Here we can already see some key terms and oppositions: ignorant mechanics, glass polishers, bootblacks, lathe turners and copies stand in opposition to art works, imagination, selection and gentlemen. Photography was another word for social division. Citing Peter Le Neve-Foster, Stillman insisted that ‘photography should maintain its place in the witness-box’ if not as a clue to identity of the criminal then as ‘a certain witness to the harmony, majesty, and actual beauty of nature’.50 This did not mean running down photography, since a great engineer did not have to be an artist, the relation of photography to art, was akin to that of philosophy to poetry or ‘the school master to the singing master’. It was better, he said and his republicanism came through in this, to be ‘photographer-in-ordinary to nature than portrait painter to Her Majesty’.51

W. T. Bovey picked out a key sentence from Stillman, who had said: ‘With mechanical aid and guidance, photography truthfully transcribes; ergo, it produces that which is not art.’52 Bovey rightly observed that Stillman was separating out:

‘art’ as opposed to ‘the arts’, which last he stintedly defines ‘arts of execution or technical achievement’. The term art, which when not proceeded by the definite article, he interprets as ‘an art of design’ implying, I presume, that it designs before it executes.53

Photographers responded by attempting to subjectivize themselves, stressing the guiding intelligence behind the camera. Stillman gave a list of the techniques that photographers tried to assert their presence: ‘the contrivance of Rembrandt tricks, and double printing’; the ‘multiplication of dodges, &c.’; ‘designing a picture, and picking up parts here and there to print together in one whole’.54 The latter referred directly to the work of Robinson and Cherrill. In any case, Bovey had put his finger on the wound by noting Stillman’s distinction between art and the mechanical arts. It is a story of architects and bees. Among the many published comments in this dispute, Albert Dumsday drew attention to Dr Nuttall’s distinction between mental arts that required ‘the exercise of mind more than that of the body’; and physical arts ‘in which manual labour is chiefly concerned including the various trades and manufactures’. The mental arts were subdivided into ‘Liberal, Polite, and Fine arts’. This is a neat summary of an old dichotomy in Western thought running back at least to Plato and structured around the mental/manual labour couplet.55 Dumsday would like to have included photography in the Liberal Arts, but he knew that painting depended on the ‘mind’s eye’ and photography on the ‘bodily eye’. Where painting was an ideal art, photography was a material one.56 On the one side was the mind and the imagination and on the other the material body. The distinctions between ‘noble’, ‘worthy’ and ‘cultivated’ mental work and vulgar labour – between the ‘mind’ and the ‘hand’ or ‘body’ – structured thinking on art and work from the ancients through the Renaissance and Reynolds up until the nineteenth century and beyond. It is interesting that shoes play such a profound role in this debate.

You will remember that Stillman compared photographs as records to the work of the shoeblack. Jacques Rancière has constructed an account of art, knowledge and work in which the lowly shoemaker plays a prominent figural role. This is not the place to discuss Rancière’s anti-foundational philosophy of equality and its relation to Marxism; there are overlaps, but the difference is marked and the perspectives are not easily reconciled. Here, I am concerned with the way that he has revealed the shoemaker as a structuring point for orders of knowledge in philosophy and sociology from the ancient Greeks to our own time. High-flown language, the language of experts, has often been produced by allocating the shoemaker a fixed place outside thought; think of Pliny the Elder’s tale of the ignorant shoemaker who dared to criticize details in a painting by Apelles and was told that he should ‘stick to his last’ – a phrase still used in English for someone who speaks of things beyond their competence. According to Rancière, the rule of anti-egalitarian thought turns on the distribution of roles or places; artisans are expected to stick to their task and know their place. At the same time, the shoemaker poets of early nineteenth-century France, in refusing to accept their place in the social hierarchy and aspiring to write poetry or philosophy, confounded the allotted positions of class.57 It is in this mixing of roles or crossing of lines that Rancière locates equality. His argument need not be confined to his French examples. Looking back from 1880, Thomas Frost recalled spending time with Jem Blackaby ‘in the shoemaker’s garret, talking by turns of politics and poetry’.58 These two Chartist cobblers made no distinction between politics and poetry; it was the elision that made them who they were, enacting a double dislocation from the worker’s world that was simultaneously a claim to social transformation. In Street Life in London, the shoeblack, even lower than shoemakers, stands for a form of work that encapsulates the social division of mental and manual labour and positions photography with the latter.

A critical examination of the photographic writing of the period reveals that art and labour are mutually exclusive categories, and yet they depend on each other for their values and associations. The concept of the artist as a free subject rests on the ideology of the worker as a servile copyist: the worker is a man, or woman, without a mind who must work because he or she is not free to determine their own destiny. The worker in bourgeois ideology is narrow, constrained and lacking in imagination. The claims that begin to be made in the 1860s for the photographers as artistic subjects inscribed a contradiction at the heart of the practice. The veracity of the photograph – its intellectual force – depended upon its being ascribed the attributes of mechanical labour. This conception of photography established a hierarchy of the forms of work with the artist at its apex. In the contrast of mechanical and intellectual labour – of vulgar photographs and elevated art – a dialectical relation was set in train. The mechanical character of the photograph emancipated the artist in a way the traditional historians of art could not imagine, since it occupied the structural position of manual, rather than intellectual, labour. In doing so, photographers found themselves playing the role of under-labourer, or maid servants, or slave, to the artist, who had been cast as the subject who was at the furthest remove from the world of work. This relation could be mobilized internally and externally. Internally, it demarcated photographic pictures from photographic documents; externally, it separated photography from true art. Professional photographers needed the language of art – often in a full academic idiom – in order to assert their own subjective presence in the face of the contaminating apparatus.59 At the other pole of this dialectic stood the document – a subjectless and immediate form. To make pictures with a machine was tolerable – important even – only so long as no one claimed these images were art works. The moment that claim was made, then both the truth content of the document and the work of a free and liberal subject were called into question. The field of debate was fluid, but the practice we know as photography is made from the fragments produced in this collision of worlds.

Stillman was smart. He knew that that photography did not slot simply into the available conceptions. He wrote: ‘When photography condescends to flatter and be agreeable, and tries to make things prettier than they are, it is of no importance what it does, it is damned as photography and fallacious as art.’ This is not so far from Baudelaire’s view.60 It might seem that he advocated that modernist old chestnut a ‘new form of communication’; after all, he did say that ‘every guild must define its own qualifications’. The real point is that he located photography on the wrong side of a divide. Photography was a useful art, as well as industrial, but it most definitely is not an art of design, but of record. Just to give one last telling citation from this important paper, he said:

I mean that photography is an art-science, and has nothing to do with anything but truth and the best way to tell it; and that it is, therefore, the antipodes of art, as science is of poetry, just the other pole of representation – the essential elements in one being imagination and the expression of artistic individuality; and of the other, the absolute physical fact.61

This is about as clear as statement as could be imagined of what Lukács in History and Class Consciousness called the ‘antinomies of bourgeois thought’, or what Allan Sekula, following Lukács, described as the ‘chattering ghosts’ of bourgeois art and bourgeois science that shape what we might call photography’s hauntology.62 Photographers needed this dirempt practice, but they did not want to admit to it or talk about it, certainly not with this kind of directness. They preferred to shuffle between poles, covering themselves with the lustre of art while deploying the mechanical guarantee. For his lucidity, Stillman drew their ire. The editor of the Photographic News responded, stating that Stillman ‘utterly erred’ and referring to his ‘pernicious error’ and his ‘cardinal error’.63

The debate went on and on, circling the same basic distinctions and antimonies.64 Stillman shifted his terms somewhat, focusing on hand work, but his argument remained basically the same. Photography is ‘an art’ or an ‘art-science’. The editor intervened insisting that photographers had refuted all of Stillman’s arguments, and yet again Stillman replied.65 The arguments continued, without anything substantive added to the basic distinctions. In fact, these same oppositions have been repeated throughout much of the history of photography. The year 1888 – in which George Eastman launched his Kodak – represents one moment in a process of pathological repetition. It was the development of the second wave of amateur photography that once more injected a tone of ressentiment into the photographic press. For one thing, the rise of the amateur was already well under way when Eastman made his contribution. For example, John Taylor has examined the vituperative tone that permeates the writing of P. H. Emerson and that is fixed on the new amateurs and day-trippers.66 In the debates of the 1880s and 1890s, the amateur appeared to transport the characteristics of the vulgar and the mass into photography itself. The figure of the amateur opened old wounds, and again suggested the photographer’s proximity to the world of work. This argument is equally applicable to the very different aesthetic tendency of Pictorialism, which came to the fore in the closing decades of the nineteenth century. All that gum-smudging offered another petty-bourgeois utopia of art. Take, for instance, the category of ‘fuzziness’ that appeared in an exchange in the British Journal of Photography in 1897. J. H. Baldock, defending the concept of sharp pictures, wrote: ‘Fuzziness, I take it, is one of the attempts to make a photographic picture rival a hand painted-picture. As well might a player on the barrel-organ try to emulate Paganini on his violin!’67 While C. Moss in the same debate argued:

It may be, and is, argued that the camera is a machine and therefore cannot give anything but mechanical results, and, consequently, photography is doomed to stand for ever outside that circle of art to which painting and drawing are admitted.68

The only thing that it seems appropriate to say at this point is déjà vu.

2 John Thompson, ‘The Wall Worker’, from Street Life in London, 1877/8. Library of the London School of Economics and Political Science, R(SR)/1146.

Despite the many changes that have taken place, the splits between elevated and base, esteemed art and vulgar document, artist and worker, remain the ordering conditions of photographic knowledge. But these days the allotropic form and its allegorical shadow are simply assumed rather than openly debated. The terms of this structure run through the avant-garde, the new social landscape and conceptual art, all the way to the practices that figure in Michael Fried’s book and considerations of tableau photography. But I want to conclude by returning to Thompson one last time, because I think there is a fragment of another vision in his book, or at least a point for allegorisis that opens up a different image of the worker, and it is one that if taken seriously might necessarily reconfigure our account of the photography. Street Life in London includes a photograph of a cobbler and two images of bootblacks. ‘The Wall Worker’ depicts three men outside a pub with one figure standing and two seated [2]. The man on the right, who has neither pipe nor tankard, is ‘Cannon’, who was once a prosperous shoemaker employing as many as thirty workers and specializing in children’s morocco boots. Mortgaged and losing skilled men to ‘sodgerin’ during the Crimean War, Cannon ended up in the workhouse. From there he became a crossing sweep and then a wall worker – hanging cheap advertising on a fence or wall. Here he is idle, a cobbler out of place. Not that we should romanticize, Cannon attributed the decline of the English tradesman to the ‘pride of the working classes’ (trade unions and strikes) and fashion. He is one of the Thompson’s figures who have come down in life, and his presence suggests that viewers in their drawing rooms might not be entirely secure. There is not much more to this example than that, and I have included it mainly for the sake of completing a little series.

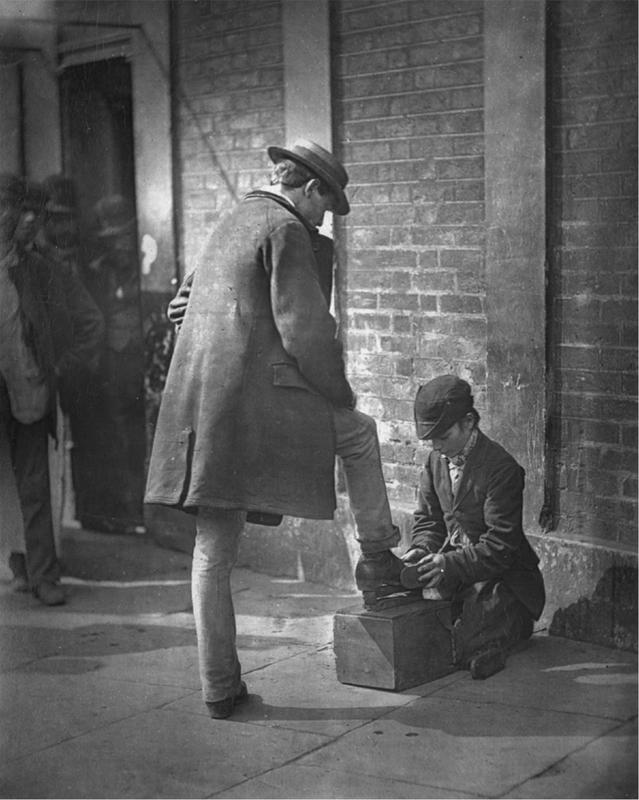

3 John Thompson, ‘The Independent Shoe-Black’, from Street Life in London, 1877/8. Library of the London School of Economics and Political Science, R(SR)/1146.

‘The Independent Shoe-Black’ concludes the volume [3]. Here a boy cleans a gentleman’s boot while four men look on; it is likely that their attention has been caught by the presence of the photographer and journalist. Smith’s narrative concentrates on the conflicts between those competing in the trade; between men and boys; the able bodied and the disabled: ‘useful, though perhaps unfair, patronage is accorded to the members of the Boot-black Brigades’ – licensed bootblacks. The story told here is of an independent black and the hardships of the trade. This is an odd choice of subject for a book or an image addressed to the respectable, because it was those organized in the Shoe-Black Brigade, with their scarlet jacket, peaked cap and identifying number, who suggested paternalistic intervention against ‘demoralization’.69 The blacks in the Brigade were licensed by the police, moralized and tolerated by the authorities, whereas an unlicensed black like the one depicted suggested a different kind of licence: the unordered life of the pauper or the ‘residuum’, usually perceived as heathen, unruly and criminal.70 Perhaps the boy is meant to present the viewer with all those associations called up by demoralized labour. Except Smith’s text openly identifies with this figure and his independence; in contrast, he suggests the Brigades and the process of licensing shoeblacks has ‘decidedly trespassed on the freedom of the street industries’.71 Gareth Stedman Jones has argued that the primary ideological lens through which pauperism was perceived in the 1870s was that of ‘demoralization’, and he links this directly to the agenda of a professional middle class in the making. Moralizing intervention was to be their task and their guarantee of authority. This photograph of a young shoeblack and accompanying text do not fit that ideological purview. Whatever its problems, Street Life in London is closer to life on the street than professional moralizers.

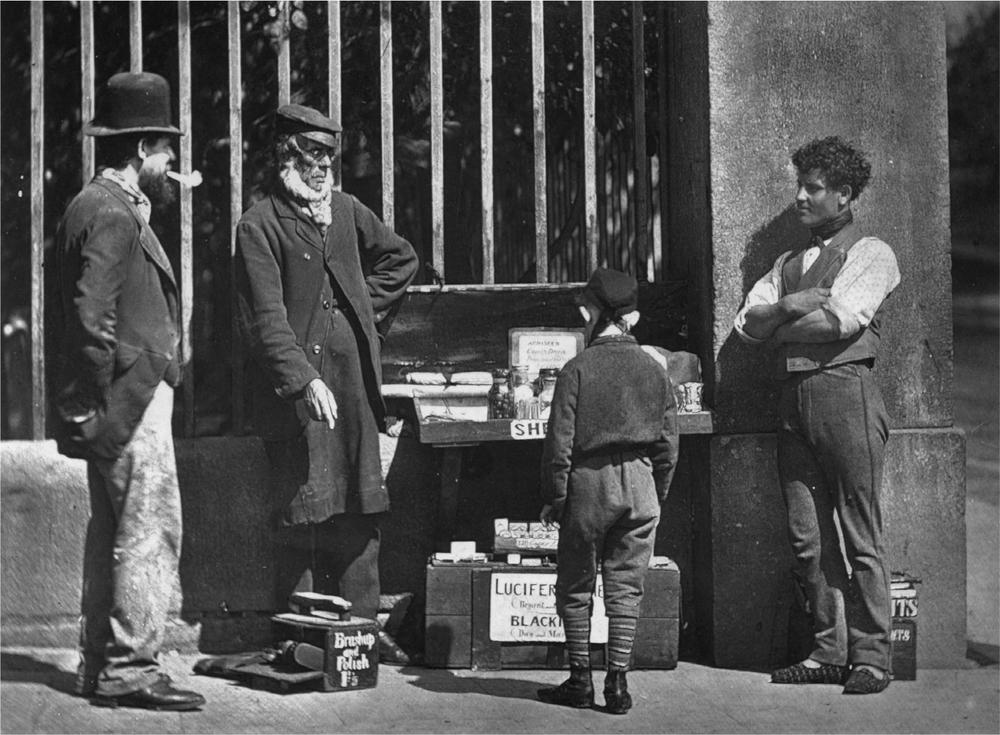

4 John Thompson, ‘Jacobus Parker, Dramatic Reader, Shoe-Black, and Peddler’, from Street Life in London, 1877/8. Library of the London School of Economics and Political Science, R(SR)/1146.

Another image [4] provides, if anything, a stronger interruption, once more pointing to Thompson’s uncertainty, but also refusing the story set out by Stillman and his critics. ‘Jacobus Parker, Dramatic Reader, Shoe-Black, and Peddler’ is represented standing at his accustomed “pitch”’.72 Seventy years old, half blind and pro-temperance, Parker had been a vellum binder in the Treasury Office, while working in his spare time in the theatre and improving himself. After an illness that cost him the sight of one eye, he left his place, failed in business with his son as an independent bookbinder and found himself in the Lambeth Workhouse. Parker discharged himself from this Bastille and made a living as a dramatic reader performing Shakespeare, Goldsmith, Burns and others on the streets. By the time Thompson found him, he was poor – living in a ‘garret’ – and combining blacking shoes with performing poetry. The presence of Parker in Street Life in London gives the lie alike to ancient philosophers and Royal Academicians, to bourgeois journalists and gentlemen photographers. The poor man may be compelled to graft and grind, but his place is not fixed or immutable. The division of mental and manual labour that shaped the categories of photography might correspond to social division, but this was a historical and not a natural process. Parker too would have liked to put behind him bootblacking and grovelling at the feet of rich men; his great dream was to perform a ‘Shakespearian evening’. We do not know if it ever came to pass, but we do know that boot blacks, even lower down the social scale than cobblers, might also contemplate poetry while cleaning shoes. How then would we need to think of photography?

1 A version of this essay was presented in 2010 at the conference ‘Why Photography Matters as Document as Never Before’, Rovira i Virgili University, Tarragona, Spain. That paper appeared in Catalan in Jorge Ribalta (ed.), Per què la fotografia és avui més important com document que mai (The Private Space Books: Barcelona, 2012), pp. 73–103. I would like to thank Jorge Ribalta, who invited me to speak and edited the conference proceedings.

2 John Thompson, Victorian Street Life in Historic Photographs (Dover Publications: New York, 1994).

3 Molly Nesbit, Atget’s Seven Albums (Yale University Press: New Haven and London, 1992). See also Nesbit, ‘The Use of History’, Art in America, vol. 74 (February 1986), pp. 72–83; Nesbit, ‘Photography, Art and Modernity (1910–30)’, in Jean-Claude Lemagny and André Rouillé (eds.), A History of Photography: Social and Cultural Perspectives (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1987), pp. 103–23. For a detailed account of Nesbit’s argument, see my review ‘A Walk on the Wild Side: Atget’s Modernism’, Oxford Art Journal, vol. 16, no. 2 (1993), pp. 86–90.

4 Ibid., p. 16.

5 Foucault has recently reappeared as a different kind of thinker.

6 John Tagg, ‘A Means of Surveillance: The Photograph as Evidence in Law’, in The Burden of Representation: Essays on Photographies and Histories (Macmillan: Basingstoke, 1988), pp. 66–116; David Green, ‘On Foucault: Disciplinary Power and Photography’, Camerawork, no. 32 (1985), pp. 6–9; ‘A Map of Depravity’, Ten.8, no. 18 (1985), pp. 37–43.

7 Tagg, ‘A Means of Surveillance’, op. cit., p. 92.

8 Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (Penguin: Harmondsworth, 1977), p. 25.

9 John Thompson in Vicki Goldberg (ed.), Photography in Print (University of New Mexico Press: Albuquerque, 1981), p. 164.

10 Tagg, The Burden of Representation, op. cit., p. 6.

11 ‘Christmas Books’, The Graphic, 1 December 1877.

12 ‘Illustrated Books’, Daily News, 26 November 1877.

13 Foucault’s late lectures addressing ‘biopower’, ‘biopolitics’ and ‘subjectivization’ provide a different perspective and one of more interest to contemporary Marxists. See, for example, Michel Foucault, Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the Collège de France (Picador: New York, 2007); The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the Collège de France (Picador: New York, 2008). Foucault’s late lectures and writing made an impact on a range of radical thinkers from Daniel Bensaid to Toni Negri.

14 Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (Vintage: London, 1993); Geoffrey Batchen (ed.), Photography Degree Zero: Reflections on Roland Barthes’s Camera Lucida (MIT Press: Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2011); Michael Fried, Why Photography Matters as Art as Never Before (Yale University Press: New Haven and London, 2008). This is to reduce neither Barthes nor the debates on his work to this symptom. It is also fair to note that Fried has his own long-standing agenda.

15 Mike Weaver, ‘Henry Fox Talbot: Conversation Pieces’, in Mike Weaver (ed.), British Photography in the Nineteenth Century: The Fine Art Tradition (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1989), pp. 11–23; Weaver, ‘Diogenes with a Camera’, in Weaver (ed.), Henry Fox Talbot: Selected Texts and Bibliography (GK Hall: Boston, Massachusetts, 1993), pp. 1–25; Helmut Gernsheim, Julia Margaret Cameron: Her Life and Photographic Work (Aperture: New York, 1975).

16 Ellen Meiksins Wood, The Retreat From Class or a New ‘True’ Socialism (Verso: London, 1986).

17 Art history as a discipline seems impervious to the current renaissance in Marxist theory. It is as if art historians did not have to bother themselves with Marxism once Althusser exited the scene.

18 Henry Mayhew, London Labour and the London Poor: Cycolpaedia of the Condition and Earnings of Those That Will Work, Those That Cannot Work and Those That Will Not Work, 4 vols (Dover Publications: New York, 1968).

19 Adolphe Smith, in Thompson, Street Life in London (1877); republished as Victorian Street Life in Historic Photographs, op. cit., p. 31.

20 Ibid., p. 33.

21 Ibid.

22 Ibid., p. 31.

23 David Jacobs, ‘Thompson, John (1837–1921)’, John Hannavy (ed.), Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography, vol. 2 (Routledge: New York, 2008), pp. 1387–8.

24 Thompson published The Straits of Malacca, Indo-China and China (1875) and Illustrations of China and its People (1873–4). All are available, with different titles, in modern reprints.

25 For the outsider’s view in photography, see Steve Edwards, ‘Disastrous Documents’, Ten.8, no. 15 (1984), pp. 12–23.

26 Audrey Linkman, The Victorians: Photographic Portraits (Tauris Parke Books: London and New York, 1993).

27 Ibid., p. 148.

28 In fact, I think the current mood significantly misrecognizes the relation to photography in some of the best works of conceptual art and what followed. See John Roberts, The Impossible Document: Photography and Conceptual Art in Britain 1966–1976 (Camerawords: London, 1997); Blake Stimson, The Pivot of the World: Photography and its Nation (MIT Press: Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2006); and Steve Edwards, Martha Rosler: The Bowery in two inadequate descriptive systems (Afterall: London, 2012).

29 Gareth Stedman Jones, Outcast London: A Study in the Relationship Between Classes in Victorian Society (Penguin: Harmondsworth, 1976).

30 For this debate, see Steve Edwards, The Making of English Photography, Allegories (Penn State University Press: University Park, Pennsylvania, 2006). Perhaps this is the place to acknowledge my debt to Andrew Hemingway’s work on British art and aesthetics: Andrew Hemingway, Landscape Imagery and Urban Culture in Early Nineteenth-Century Britain (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge and New York, 1992). I should also mention John Barrell’s The Body of the Public: The Political Theory of Painting from Reynolds to Hazlitt (Yale University Press: New Haven and London, 1986). Of course, that makes it necessary to point to Hemingway once more: Andrew Hemingway, ‘The Political Theory of Painting Without the Politics’, Art History, vol. 10, no. 3 (September 1987), pp. 381–95.

31 Editorial, ‘An Art Critic on Photography in Relation to Art’, Photographic News, 15 March 1872, p. 122.

32 Louis Althusser and Étienne Balibar, Reading Capital (New Left Books: London, 1970); Pierre Macherey, A Theory of Literary Production (Routledge & Kegan Paul: London, 1978). For a version of this argument in art history, see T. J. Clark, ‘On the Social History of Art’, Image of the People: Gustave Courbet and the 1848 Revolution (Thames & Hudson: London, 1974); On ‘structure of feeling’, see Raymond Williams, The Country and City (Paladin: St Albans, 1975); Raymond Williams, Marxism and Literature (Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1977).

33 For the heightening of metaphorization, see Franco Moretti, Atlas of the European Novel 1800–1900 (Verso: London, 1998).

34 William James Stillman, The Autobiography of a Journalist (Houghton, Mifflin and Company: Boston and New York, 1901); Elizabeth Lindquist-Cock, ‘Stillman, Ruskin and Rossetti: The Struggle Between Nature and Art’, History of Photography, vol. 3, no. 1 (1979), pp. 1–14; Barbara Rotundo, ‘William James Stillman’, in Catalogue of the William James Stillman Collection (Friends of the Union College Library: Schenectady, 1974), pp. xi–xxi; Deborah Harlan, William James Stillman: Images in the Archives of the Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies (Council of the Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies and Council of the British School at Athens: London, 2009).

35 William James Stillman, The Acropolis of Athens: Illustrated Picturesquely and Architecturally in Photography (F. S. Ellis: London, 1870).

36 His two-volume autobiography contains the odd line on his photographic activities, but there is not a word about the controversy. He mentions having to leave his photographic apparatus when fleeing down a mountain in Crete; he notes that when his first wife was dying in Crete, he himself ‘was prostrated mentally and physically, and unfit for anything but my photography’; he also refers to the publication of his Athens photographs, which he said ‘cleared for me about $1000’. William James Stillman, The Autobiography of a Journalist, op. cit., vol. 2, pp. 62, 69, 76. This is not unusual; these disputes mattered for photographers, but were incidental matters for those bourgeois professionals who became embroiled in them. See, for example, the autobiography of Frederick Pollock, Personal Remembrances of Sir Frederick Pollock, Second Baronet, 2 vols (Macmillan: London, 1887). For many years, Pollock was president of the Photographic Society, but this activity does not figure in his large book.

37 Edwards, The Making of English Photography, Allegories, op. cit.

38 An Indignant Photographer, ‘The Art Controversy’, Photographic News, 8 March 1872, p. 117.

39 William James Stillman, Year-book of the Photographic News, 1872, p. 51.

40 Ibid.

41 H. P. Robinson, Pictorial Effect in Photography, Being Hints on Composition and Chiaroscuro for Photographers (Piper & Carter: London, 1869).

42 Theophilus Thiddlemitch, ‘Recent Opinions of Photographic Art’, Photographic News, 9 February 1872, p. 68.

43 Ibid. It is notable that Peter Le Neve-Foster was expressing similar views about Robinson’s work: ‘clouds gone mad’. For this, Thiddlemitch sanctioned and forgave him, but not Stillman. See also W. T. Bovey, ‘Mr, Foster and his Critics’, Photographic News, 16 February 1872, p. 78.

44 William James Stillman, ‘The Art Question’, Photographic News, 16 February 1872, p. 80.

45 Ibid. According to Stillman, photography ‘may substitute an agreeable and well composed sky for a bad one, a good corner of a hedge row for a bad one – may even, by judicious turning a head this way or that, hide the worse and show the better view of a face; but it still remains what the lens sees it and the camera records. With all your thinking you cannot make a hair that is white on the screen come black on the film.’

46 H. P. Robinson and N. K. Cherrill, ‘The Art Question: In Reply to Mr Stillman’, Photographic News, 23 February 1872, p. 94. They added a note that In the Gloaming was the least appropriate of their pictures for the kind of error Stillman thought he had found, implying it was not a combination print.

47 Stillman, ‘The Art Question’, op. cit., p. 105. Spinoza earned his living as a glass polisher, and if I were really clever I would work that in here.

48 Ibid., p. 106. He continued: ‘I have seen a machine, in fact in which a person might be laced, and accurate measurements be taken, at hundreds of points, of his figure, and then a mass of clay substituted for him, the points closed in again, left his figure completely indicated in the clay, so that only the intervals between the points needed to be cut away to make the entire statue, accurately roughed out. Will my opponents admit that in either of these cases the operator is an artist? If not, in what sense is the photographer as such, an artist; and if a good photographer is not necessarily an artist, how can photography be asserted to be Art?’

49 See Edwards, The Making of English Photography, Allegories, op. cit.

50 Stillman, ‘The Art Question’, op. cit., p. 106.

51 Stillman, Year-book of the Photographic News, op. cit., p. 51; Robinson and Cherrill, ‘The Art Question: In Reply to Mr Stillman’, op. cit., p. 117. Robinson and Cherrill responded by claiming that ‘Mr. Stillman runs into the fatal error of separating the man and the means. We have never claimed for photography that it could do pictures by turning a handle.’ The same point is made by another critic who noted the ‘ever recurring controversy’ about art and photography ‘consists in confounding the unintelligent means with the intelligent agent and in measuring the result by the method.’ Anonymous, ‘An Art Critic on Photography in its Relation to Art’, Photographic News, 15 March 1872, p. 122.

52 Bovey, ‘The Art Question’, op. cit., p. 127.

53 Ibid.

54 William James Stillman, Letter, Photographic News, 15 March 1872, p. 129.

55 For a consideration of these distinctions in the contemporary literature of photography, see Antoine Claudet, ‘The Art Claims of Photography’, Photographic News, 20 September 1861, p. 447. For the extended ramifications, Edwards, The Making of English Photography, Allegories, op. cit. Also of interest is Joel Snyder, ‘Res Ipsa Loquitur’, in Lorraine Daston (ed.), Things that Talk: Object Lessons From Art and Science (MIT Press: Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2004), pp. 195–221. For the wider debate, see Karl Marx, Capital, vol. 1 (1867) (Lawrence & Wishart: London, 1954); Alfred Sohn-Rethel, Intellectual and Manual Labour: A Critique of Epistemology (Macmillan: London, 1978).

56 Alfred Dumsday, ‘The Division in the Arts’, Photographic News, 28 March 1872, p. 155.

57 Jacques Rancière, The Nights of Labour: The Worker’s Dream in Nineteenth-Century France (Temple University Press: Philadelphia, 1989); Jacques Rancière, The Philosopher and His Poor (Duke University Press: Durham, North Carolina, 2004). For the history of militant shoemakers, see also Eric Hobsbawm and Joan Scott, ‘Political Shoemakers’, in Hobsbawm, Worlds of Labour: Further Studies in the History of Labour (Weidenfeld & Nicholson: London, 1984), pp. 103–30.

58 Mike Sanders, The Poetry of Chartism: Aesthetics, Politics, History (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2009), p. 6.

59 Edwards, The Making of English Photography, Allegories, op. cit.

60 Charles Baudelaire, ‘On photography’ [1859], in Beaumont Newhall (ed.), Photography: Essays and Images (Secker & Warburg: New York, 1981), pp. 112–13.

61 William James Stillman, Letter, Photographic News, 15 March 1872, p. 129.

62 ‘The antimonies of bourgeois thought’ is the title of Section II of Lukács’s great essay ‘Reification and the Consciousness of the Proletariat’, in Georg Lukács, History and Class Consciousness: Studies in Marxist Dialectics, trans. Rodney Livingstone (Merlin Press: London, 1971). This idea was applied to photography by Allan Sekula: Allan Sekula, Photography Against the Grain: Essays and Photo Works 1973–1983 (The Press of Nova Scotia College of Art and Design: Halifax, Nova Scotia, 1984), p. xv. For ‘hauntology’, see Jacques Derrida, Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning, and the New International (Routledge: London, 1994). Much of the subsequent debate is collected in Michael Sprinker (ed.), Ghostly Demarcations: A Symposium On Jacques Derrida’s Specters of Marx (Verso: London and New York, 1999). For a different version of Gothic Marxism, see David McNally, Monsters of the Market: Zombies, Vampires and Global Capitalism (Brill: Leiden, 2011).

63 Editorial, ‘Is Photography a Fine Art?’, Photographic News, 28 March 1872, p. 145. 64 Stillman reiterated: ‘The proper function of photography is the recording of truth – facts, if you please – and that any work which has been mended for the sake of pictorial modifications, or to make it resemble a work of design (as I use the word), has lost just so much of its value as a photograph – that, in fact, so-called art-photography (i.e., employing photography to produce artificial combinations) is not increasing, but diminishing the value of the result, and is, in fact, really an obstacle to the perfecting of the true art of photography, just as retouching is a cause of toleration of much bad work, and of much photographic shortcoming.’ William James Stillman, ‘The Art Question: An Explanatory Rejoinder’, Photographic News, 5 April 1872, p. 165.

65 Editorial, ‘Is Photography a Fine Art?’, op. cit., pp. 169–71; W. J. Stillman, ‘The Art Question’, Photographic News, 12 April 1872, p. 179.

66 John Taylor, ‘Landscape and Leisure’, in Neil McWilliam and Veronica Sekules (eds.), Life and Landscape: P. H. Emerson – Art and Photography in East Anglia, 1885–1900 (Sainsbury Centre for the Visual Arts: Norwich, 1986), pp. 73–82; ‘The Alphabetic Universe: Photography and the Picturesque Landscape’, in Simon Pugh (ed.), Reading Landscape: Country – City – Capital (Manchester University Press: Manchester, 1990), pp. 177–96; ‘Travellers, Tourists and Trippers on the Norfolk Broads’, A Dream of England: Landscape, Photography and the Tourist’s Imagination (Manchester University Press: Manchester, 1994), pp. 90–119.

67 ‘Sharp Versus Fuzzy Photographs’, British Journal of Photography, 31 December 1897, pp. 840–2. It should be noted that the categories of ‘fuzziness’ and ‘woolliness’ are to be found in the middle of the 1860s.

68 Ibid.

69 For a discussion of the shoeblack and the Brigades in paintings of the period, see Nancy Rose Marshall, City of Gold and Mud: Painting Victorian London (Yale University Press: New Haven and London, 2012), pp. 169–77.

70 Jones, Outcast London, op. cit.

71 Thompson, Street Life in London, op. cit., p. 131.

72 Ibid., p. 47.