READING AHAB

ROCKWELL KENT, HERMAN MELVILLE AND C. L. R. JAMES

‘All great books are symbolical myths, overlaid like a palimpsest with the meanings that men at various times assign to them.’ Clifton Fadiman1

In 1930, two editions of Herman Melville’s Moby Dick appeared, both illustrated by Rockwell Kent.2 A leading American artist of the interwar years, Kent had already made a considerable contribution to the revival of book arts, fuelled by the desire to raise publishing standards while at the same time encouraging greater public interest in the classics. Kent’s broad reading – evident in a considerable personal library of the classics from Chaucer to Shakespeare, Voltaire and Melville, along with the Russian works of Gorky, Tolstoy and Turgenev – prepared him well as an illustrator; his sense for what the artist Abbott Thayer called ‘interstellar austerities’ earned him a request from no less than Thomas Hardy, who wished to have him illustrate a collection of late poems.3

By 1930, Kent’s reputation as an image-maker and illustrator was so considerable that the editors at Random House not only gave him top billing in the design of the book, but left off Melville’s name altogether.4 The oversight was satirically marked by Robert Frost in a poem of 1947: ‘There is a story you may have forgotten / About a whale. / Oh, you mean Moby Dick / By Rockwell Kent that everybody’s reading.’5 For the commission, Kent made black-and-white pen-and-ink drawings that laboriously reproduced the appearance of woodcut (and wood engraving), drawings that were then translated for the deluxe edition into woodcut itself.6 The choice may seem odd; unlike illustrators of other editions of Moby Dick from the 1920s and 1930s, Kent interpreted Melville through the lens of an anachronistic medium that was itself contemporaneous with the history contained in Moby Dick. In doing so, his illustrations added one further layer to the dense texture of historical and mythic references that characterize the great book. Paralleling Melville’s own encyclopedic range of genres, Kent mined a variety of historical styles, referring not only to sixteenth-century European engravings and nineteenth-century woodcuts and almanacs, but also to emblem books, and Blake-inspired nudes.7

On receiving his assignment, Kent avidly researched the history of whaling at the Museum of Natural History in New York and the New Bedford Whaling Museum, driven by his own interest in the whaling communities he encountered while residing in Maine and Newfoundland. But his illustrations far exceeded an antiquarian approach. Skilfully matching the retrospective quality of Melville’s own narrative of whaling, which already by 1851 appeared in a historical light, Kent also captured something of the mythic quality of the book, a text that produced inexhaustible meanings for generations of readers. Published in the years when the nation lurched forward into industrial modernization, Moby Dick arced across the decades to link the founding of the republic with its unrealized destiny.8

In what follows I hope to demonstrate that Kent’s version is as interesting for its blind spots as for its considerable power in translating Melville’s text for his own generation. These blind spots are most apparent in relation to the politically charged figure of Ahab at the centre of the book, whose meaning unfolded across several generational and historic registers both before and after Kent tackled the subject. In an extraordinary interpretation of Moby Dick, written by the Trinidadian Marxist intellectual and writer C. L. R. James twenty-three years after Kent’s illustrations, we may locate the elements of a radically different understanding of the book. James’s Mariners, Renegades, and Castaways fully articulates the implications of the ‘totalitarian’ personality for artists and writers on the left, a historical type yet to emerge when Kent contrived his Ahab in 1930. Bracketing either end of the period that witnessed the global rise of fascism and the Second World War, Kent’s and James’s readings of Melville make glaringly apparent the shift in the political valence of personality following the rise of Hitler and Stalin, and expose one source of the ambivalent allegiance to collectivism within the American left itself.

The choice to illustrate Moby Dick was Kent’s: the book resonated with his own myth-inspired imagination, sense of epic grandeur, and taste for forbiddingly desolate landscapes. From the beginning of the commission, William Kittredge – director of design and typography at Lakeside Press – perceived a strong fit between artist and author. He wrote to Kent, ‘it is as though you were working side by side – Melville with words and you with pictures’.9 Both artists confronted a world that – in 1850 and again in 1930 – seemed on the brink of vast and tumultuous changes, an unsettling of fundamental political and social landmarks and structures of value. Both decades ignited a sense of cultural doubt and self-appraisal at parallel periods of political and social crisis.

For the commission, Kent made 135 drawings for each of the chapter headings; another 95 appearing at chapter conclusions; 23 full-page illustrations; and 8 half-page designs, along with a range of epigrammatic or emblematic medallions and smaller images scattered throughout the text. Exploiting the stark tonal contrasts of the woodcut medium he was emulating in his pen-and-ink drawings, he produced a series of formally distilled, highly stylized images [1]. As a bitonal medium, woodcut flattened tonal gradation in favour of starker dark and light value contrasts, largely restricting or eliminating the chiaroscuro gradations and subtle tonalism possible in other print media such as acquatint, lithography or even wood engraving. Far removed from the symbolist suggestiveness of Pictorialist photography that emerged a few decades after Melville’s book, woodcut nonetheless captured Kent’s vision of Moby Dick. He wrote to Kittredge that Moby Dick was ‘a most solemn, mystic work, with the story and the setting serving merely as the medium for Melville’s profound and poetic philosophy.… The color, so far as I can see, is determined; night, the midnight darkness enveloping human existence, the darkness of the human soul, the abyss.’10

1 Rockwell Kent, ‘Moby Dick’, from Moby Dick (R. R. Donnelly and Sons Company, Lakeside Press: Chicago, 1930), letterpress and woodcut, vol. 1, p. 273 (chapter 41).

This allegorical turn of thought in Kent’s response to Moby Dick also characterized how he translated the book into visual imagery. His choice of woodcut, as I would like to argue, served his personally inflected reading, and in the end brought him closer to Ahab than to Melville. His own dramatic (and self-inflating) account of why he was drawn to woodcut was staged in Melvillian rhetoric of dark and light: ‘How like the night the wood block, coated black! How like a shaft of light the tool that cuts the black – and by its touch illuminates an object hidden there! Wood, then, shall be, must be, the medium.’11 Woodcut – with its stark value contrasts – also captured contemporaneous readings of Melville’s book as a universe defined around the moral polarities of good and evil. Lewis Mumford’s 1929 account, for instance, noted the sudden manner in which the early naturalism of the opening chapters disappears from the book with the arrival of Ahab: ‘Once Moby Dick gets under way, the fable itself belongs to Heaven and Hell,… so that everything which would relieve men’s exasperation or take the edge off their lonely delight, disappears, as the land disappears beyond the horizon’s edge.’12 This impulse to read Ahab in terms of conventional moral polarities, however, falls short of realizing the full philosophical complexities of the book; the black-and-white values of the woodcut medium at times worked poorly with its wealth of symbolist association, its moral tenebrism, its elusive and shaded multiplicity of meanings.13 Nonetheless, these symbolist qualities helped drive the literary rediscovery of Melville – finding its counterpart in the contemporaneous revival of interest in the art of Albert Pinkham Ryder.14 Despite the limited suggestiveness of woodcut, it was a medium that would prove peculiarly well adapted to representing Ahab, the ‘godless godlike’ captain of the Pequod, whose quest for absolute meanings and control of an indecipherable universe drove the collective fate of the shipboard community.

Manipulating the relative ratio of white to dark that constituted the primary expressive dimension of woodcut, Kent introduced a range of different moods into his illustrations for Moby Dick, modulating from daytime vistas of the ocean to the sooty dark imaginings of Melville’s more psychologically charged passages. Kent’s imitation of woodcut and wood engraving also proved versatile enough to capture the shifting moods and landscapes of the book. The genre-like quality of its opening chapters, for instance, found expression in charmingly naive, toylike images reminiscent of eighteenth-century New England street signs: ‘genre pictures in the manner of Teniers, with a dash of Hogarth or Rowlandson’, as Mumford put it, belonging ‘to the land and its … little ways’.15 After these accurately detailed opening passages, however, the book takes a profoundly different turn.

By the 1920s, Moby Dick was no longer understood as a boy’s adventure story about a man and a whale. Indeed, the reception history of the book from that point on revealed, in Nick Selby’s words, ‘a changing understanding of what America and its culture might mean’.16 Any consideration of Kent’s illustrations must reckon, therefore, with both the extent to which they engage the broader histories of the nation and with Kent’s own psychological profile, deeply imprinted with the peculiar vulnerabilities and obsessions of those decades of crisis and national reinvention between the wars. Three years in the making, Kent’s drawings participated in – and contributed to – the Melville revival taking shape between the two world wars. Charting nothing less than the voyage of the American soul, to paraphrase D. H. Lawrence, Moby Dick drew powerful responses from a range of critical voices.17 The interwar rediscovery of Melville was driven by a fascination with his symbolic reach and his epic synthesis of different ways of knowing the world. Lawrence’s 1923 Studies in Classic American Literature helped launch the symbolic reading of Melville’s dark book; of the whale, he wrote ‘Of course he is a symbol.’18 Lawrence read Moby Dick as an allegory of the ‘ghastly maniacal hunt’ of a doomed white race, severed from self-knowledge by its alienation from a mythologized blood consciousness – a source of cosmic wholeness without which European post-Enlightenment culture would atrophy. If Lawrence found the book’s ‘esoteric symbolism’ to be of ‘considerable tiresomeness’, he still proclaimed Melville ‘a deep, great artist’.19 In its scepticism towards positivist science, and towards the fixed certainties of natural taxonomies and inherited categories of meaning, Melville’s book spoke to the critical engagements of the artists and writers in the 1920s who grappled with the celebratory myths that underwrote the expansion of business and what Mumford called ‘the harassed specialisms which still hold and preoccupy so many of us’.20 Mumford found in Moby Dick a fully realized and richly symbolic universe.21 Melville furthermore heralded a new ‘interAmerican … hemispheric’ sensibility; questioning the foundations upon which his contemporaries built their ‘vast superstructure of comfort and complacency’, Melville refused to shrink ‘from the cold reality of the universe itself’.22

The Melville revival was part of a growing awareness of American history and culture that characterized the second generation of modernism in the United States. Over the next decade, artists and writers, following the call of cultural critics such as Van Wyck Brooks, writing for the little journal Seven Arts, turned to cultural resources grounded in their own native experience to forge new pathways into their histories. They explored issues of cultural and national identity through the lens of such mythic figures as Columbus, the Puritan, the pioneer and the voyager.23 This interest in the mythic construction of America took many forms in these years, from F. Scott Fitzgerald’s invocation of the ‘green breast of the New World’ at the end of The Great Gatsby, to the revival of sixteenth-century maps of the New World by New Yorker cartoonist John Held to satirize the growing gap between America’s original promise and its current degradation by standardized commerce. All of these texts were part of a broader cultural effort to reclaim the mythic dimensions of American identity from a society desiccated by the effects of mass culture, consumerism and sham. The famous conclusion of Gatsby, in particular, invokes the wonder that accompanied the original encounter with the New World, only to reflect upon its fatal and tragic historical course. Recollecting this capacity for wonder, Fitzgerald then proceeded to his melancholic meditation on the breach between myth and history. For this interwar generation, Moby Dick reignited a sense of the immeasurable scale of the universe, a scale reasserted in face of the blighting quest of Ahab at its centre.

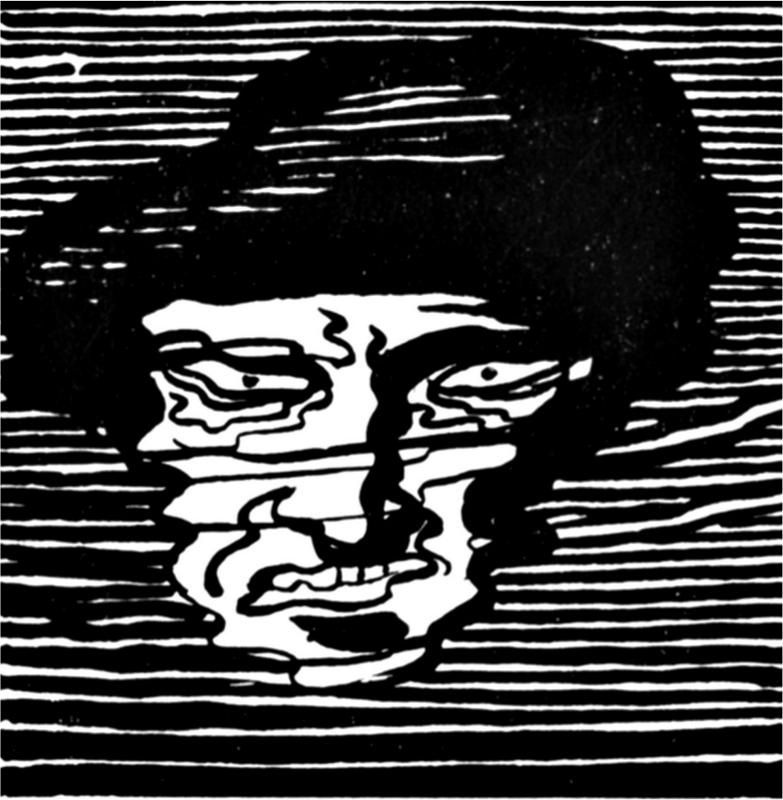

2 ‘Ahab’, vol. 1, p. 179 (chapter 28).

The immensity of Melville’s themes call upon an imagistic power that exceeded Kent’s emblematic imagination and his jewel-like images. Kent was limited both by his own imaginative disposition and by the black-and-white medium he chose, which ill equipped him to visualize a universe that resisted – like the white whale at its heart – the contracted and finite measures of individual significance. Kent’s illustrations best match Melville’s text when it is most emblematic, as for instance in ‘Ahab’ [2], in which the elusive captain first appears on deck. Ishmael notes the ‘slender rod-like mark, lividly whitish’ and resembling the seam made in a lightning-struck tree that runs like a brand down Ahab’s face and neck, and – he imagines – continuing perhaps from crown to sole. Kent translated this passage into its most metaphoric terms: lighting striking the trunk and tangled roots of a great tree in an abstract composition that opens the chapter.

Kent’s most symbolically charged images are those least tied to the explicit narrative of the novel – for instance, the spectral image of the giant squid [3] projected onto a cosmic scale that expands across the horizon – gently cradling, or engulfing, the frail whaler in an ambiguous image of protection threatening destruction. Kent uses the woodcut style to desubstantialize the mass of the squid in a manner that bridges the narrative and the symbolic. His activation of this more symbolist imagination is largely outweighed, however, by a mode of image-making that seems to issue from Ahab’s own Manichean vision of a universe defined around clear dualities of good and evil. The compositions themselves – full-page illustrations, vertical in orientation, and organized around a horizon line dividing the sea from the heavens – play off the ‘abyss’ of marine darkness against the vastness of the star-studded skies in an allegory of an imprisoning nature and a celestial realm of freedom. This form of pictorialization served the two-dimensional universe of allegory, but flattened Melville’s far more ambiguous and environmentally complex vision.24

3 ‘Squid’, vol. 2, p. 136 (chapter 59).

Kent’s Ahab both builds upon and complicates the characterization that Melville offers in the text by borrowing from a Freudian discourse of repression and psychosis within which the loss of the character’s leg is linked to a sexual wound. This allusion to castration is there in Melville’s text, but it takes a more explicit form in Kent’s interpretation. 25 Ahab’s monomania – in this Freudian narrative – is the product of his wounded manhood. Other illustrations suggestively link his compromised masculinity to his will to dominate nature. The illustration for ‘The Quadrant’ draws a link to the specifically phallic quest for mastery of the sea; Ahab’s leg – amputated at the knee – projects from the crotch as if to suggest that scientific instruments are a substitute for the lost wholeness of Ahab the man [4]. In chapter 106, Ahab’s ivory leg causes him an accident of such severity that it pierces his groin, an injury whose associations with castration Kent renders explicit in one illustration.26

4 ‘The Quadrant’, vol. 3, p. 171 (chapter 118).

Ahab’s tyrannical will is also linked to the imperial arrogance of the nation itself and associated with the fate of the Pequod, named after a tribe of New England Indians fighting against extinction. The link between Ahab and the ill fate of the community he leads is most powerfully invoked at the end of the book, when a sky-hawk is pinioned by the harpooner Tashtego as he grasps the spar of the main mast of the sinking whaler subsiding into the waves. ‘[H]is whole captive form folded in the flag of Ahab’, the bird of heaven is drawn down into the ‘great shroud of sea’ like the archangel Michael to whom he is linked, ‘his imperial beak thrust upwards’. If Melville’s earlier work had implied a spread-eagle patriotism that granted the nation its historical exceptionalism, he had, by the time he wrote Moby Dick, arrived at a far darker vision of the historical forces driving the nation’s destiny, a vision realized in this, the book’s penultimate image.27 Kent’s image of Tashtego sinking beneath the sea is matched on the next page by an image of Ishmael – arm shooting towards heaven – borne skyward by the buoyancy of the coffin that saves him [5, 6]. Kent’s illustrations offer their own commentary on the text, pitting the destructive energies of ‘the flag of Ahab’ against the salvation offered to the one individual who – Kent’s image seems to imply – was able to buck the charismatic hold of Ahab over his crew. What Kent suppresses in this pair of images, however, is the orphaned condition of Ishmael himself in Melville’s text: utterly abandoned in the vastness of the ocean, he is picked up by the emblematically named Rachel searching for her lost children. Abandoning the melancholic message at the end, Kent’s final image serves instead as an emblem of the artist-prophet and Promethean saviour of the race, miraculously resurrected – a message far removed from Melville’s tragic existential vision.

5 ‘The Chase — Third Day’, vol. 3, p. 282 (chapter 135).

6 ‘Epilogue’, vol. 3, n.p.

Kent’s emphasis on physical and psychic wounding and Promethean rebirth had relevance both to his own life and to his interwar generation. A man of energetic contradictions, Kent’s cult of self emerged in tandem with his long association with international communism.28 Isolation – alternating with periods of excessive socializing and womanizing – would become part of the repeating rhythm of his life, in a familiar pattern that carried him through three wives and considerable public fame. For Kent and others in these years of intensifying collectivism and political action, the need for isolation existed in tension with his commitments to develop new networks and new agents of collective action. This tension – between the solitary ways required by the artist and the political and topical pressures drawing artists beyond themselves – was not peculiar to Kent. In 1936, Peppino Mangravite published a statement rife with conflicting loyalties – between the need for ‘aesthetic independence’ unconstrained by social ties, and the need for ‘an association … in which all artists of standing can meet on common ground’ to act on behalf of shared concerns. Simultaneously calling for artists to mobilize in collective actions and for them to be wary of sacrificing their independence in the process, Mangravite’s message reveals the ambivalence that artists felt concerning the impact of such activity on their own production.

Committed as he was to collective organizing, and an ardent socialist, Kent gave his first loyalty to his own work; he remained somewhat indifferent to the actual working-class cultures and everyday realities of ordinary people on whose behalf such actions were dedicated. A rousing public speaker, he was never more rhapsodic than when he was writing about himself. Kent’s political allegiances were loosely formed but deeply held. As early as 1904 he was drawn to the socialist labour politics of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW); later he would become involved in the efforts to unionize artists in the 1930s, participating and speaking at the American Artists’ Congress of 1936.29 At the heart of his socialist politics was a belief in the autonomy of labour, a conviction grounded ultimately in his own frequently inflated pride in submitting to no one and remaining his own master. Along with his presidency of the Artists’ League of America, and his membership in both the American Labor Party and the International Workers Order, Kent proudly listed his union and labour credentials, including the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners of America, the United American Artists; the United Office and Professional Workers of America; the National Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union.30

Kent’s truculence in asserting his own independence, however, is hard to reconcile with his abiding loyalty to the Soviet Union under Stalin, which, unlike many of his Trotskyite colleagues, he never renounced.31 Overlooking decades of Stalinist ‘state capitalism’, he continued to believe in the possibility of a new society organized around labour, even while he professed contempt for the American working classes in the concrete.32 While never a member of the CPUSA, he refused, during the McCarthy hearings, to deny his involvement. His principled defiance all but shut down his career.33 A guest of the Soviet government in the 1950s, he was pilloried, threatened and boycotted by US arts institutions during these years.34 Kent saw his radicalism as a badge of masculine honour, recognized, alongside Paul Robeson, by the labour and union movement. In his 1955 autobiography, he represented his politics as anti-fascist well into the 1950s, casting the anti-communism for which he was persecuted as driven by the powerful fascist sympathizers he believed to be still running the government.35 His political narrative hued closely to the anti-fascism of the 1930s, long after his colleagues had moved past it and into the familiar terrain of Cold War anti-communism. Kent thus remained unmoved by the structural similarities that linked fascism with Soviet communism, similarities that would become fully apparent to C. L. R. James twenty-three years later.

Enmeshed in these contradictory impulses and commitments, Kent was bound to Melville’s book – and in particular to Ahab – by a series of complex affinities. Kent’s vision of Ahab – the isolated and solitary captain of the Pequod – bore the mark of his own personal need for self-testing in a harsh and punishing wilderness. It was out of such experiences – in Newfoundland, Alaska, Tierra del Fuego and Greenland – that his art took shape, fuelled by his legendary energies.36 Like Ahab, a man aloof and untethered by social relations, Kent fled domestic entrapments with predictable regularity, devising all manner of ways to avoid any sustained period of time at home with his first wife and growing family. His associates speculated on the reasons for his restiveness: a nomadic impulse driving him to the literal ends of the earth. Kent recounted how – motivated by a desire to subdue his own sensual nature – he sought out extreme weather and physically challenging conditions in the far north.37 Like Ahab – in flight from the comforts of his landlocked domestic haven – Kent’s rebellion against physical weakness sent him in pursuit of the rigours of harsh arctic extremes.38 It was also a reaction against his own submissive tendencies, and against a feminized entrapping nature.39 In N by E, his account of a voyage on a thirty-three-foot cutter from New York Harbor to the rugged shores of Greenland, Kent told of a terrifying moment when during his watch on board, the vessel was engulfed in a darkness ‘sullen and ominous’. Surrounded by this ‘huge brown cloudbank’, he felt his sight smothered, ‘I could have screamed for horror of it, shrieked into the silence to tear it and precipitate whatever cataclysm it so long held back.’ Such moments of suffocating terror verge on fears of self-annihilation. Kent’s sensibility required panoptic visibility; he felt stifled by darkness, unstrung by any loss of vision. It may have been this terrifying loss of a securely charted self in relation to world that drew him so strongly to the blinding clarity of northern light and space.

Kent’s self-testing shared wider anxieties about a newly vulnerable masculinity in the years between the wars: a fear intensified by the broad cultural exposure to disease and bodily fragmentation that gave rise to a range of physical regimens, and more generally, to an obsession with the impermeable and hard male body.40 Such anxieties found expression in a broader impulse in the visual culture of the interwar decades towards stark outlines and impenetrable forms, along with a movement away from what one defender of Kent called the ‘abysmal present-day slough of self-expression’.41 Kent’s characteristic rhythmic outline and his incisive silhouetted figures clearly situated against their backgrounds and often monumentally scaled in relation to the landscape, as well as the often blandly smooth surfaces of his prints and paintings, give evidence of related efforts to visually manage anxieties about psychic dissolution and loss of selfhood. He was also drawn towards subarctic climates where he was able to escape the strain of social negotiation and intersubjective exchange. Like Ahab, Kent seemed persistently to have fled ‘the interdebtedness between mortals’.42

This psychological profile may also offer insight into the artist’s tight and assertive control over his medium. At least one reviewer would link this quality of formal and technical control to Kent’s will-driven personality. In a prophetic 1927 essay, the author noted that Kent exerted ‘too strong a will … on the paint … signs of too determined a control of the substance of his medium’. Kent’s vast illuminated unpeopled landscapes imply a world without boundaries or constraints except those of nature itself. And yet ‘Within this freedom and boldness … in Mr. Kent’s pictures, there is implicit another freedom which he tends too much to deny: the freedom and miracle of the pigment, that kind of subconscious life that appears in the medium, and might be said to exist in it, just as it exists in the artist himself.’43 It is a striking anticipation of the trajectory that would define advanced American art after the Second World War, a movement towards the medium as part of the very nature in which artists like Kent – defined by the romantic frontier mythos of the previous century – were utterly unprepared to participate. The unconscious life of paint itself – like the vast watery world of the Pacific – was a world inaccessible to human will and ambition, a world over which the artist self would come to relinquish control. The medium with which Kent was most identified – wood engraving – reasserted the fine manual motor skills that had been seemingly ceded in the Second Industrial Revolution to mechanization, with the advent of half-tone and other machine forms of reproduction.44 Kent exercised his desire for control through his most fundamental aesthetic procedures. Yet these procedures soon gave way in the next generation to new attitudes towards the medium of paint and to new environmental forms of knowledge that would exceed the grand frontier romance of wilderness conquest and the subjugation of nature in its myriad forms. This presumption of control exercised upon the world of paint – or of nature – was one Kent could not give up. His own personal mythos remained deeply implicated in it. Yet even his contemporaries glimpsed how limiting his approach was, and how outmoded it soon would be. Melville’s most imagistic moments exceeded Kent’s allegorical imagination, conjuring worlds of inchoate shapes and phantasmal realities through which we glimpse other ways of being.45 As Moby Dick implies through its shifting knowledge frames and forms, it is these older inheritances – as well as more modern scientific taxonomies of knowledge – that impose conceptual limitations on the ability of Ahab and his world to move beyond their species-centric vision.

C. L. R. James’s Mariners, Renegades, and Castaways, published in 1953, was separated by only twenty-three years from Kent’s illustrations of Moby Dick. James drew explicit links between the unholy alliance of Ahab and his crew and twentieth-century mass politics; his text exposed the underlying social pathologies of an emerging world system of industrial production. For James, Ahab was the dialectical product of a world in the grip of the inanimate and deterministic forces of mechanization, industrialization and growing scientific knowledge. The totalitarian type embodied in Ahab, which James explicitly linked to both Hitler and Stalin, represented an impulse to control a set of forces created by humans and yet very quickly appearing to exceed their control.46 In place of Ahab’s world-destroying mission, James would emphasize the collective energies of the Pequod crew, from which all forms of individual hubris and charismatic self-fashioning have been burned away. James affirmed the power of ordinary men, united by labour and a shared liberatory quest across geographical and cultural divides, a dimension nowhere apparent in Kent’s focus on Ahab.

What makes James’s analysis of particular interest is that he acknowledges Ahab as a product of a specifically American historical environment. James writes that, ‘He has been trained in the school of individualism and an individualist he remains to the end.’47 From his historical vantage, James captured with great force the relationship of extreme forms of individualism to the rise of totalitarian drives in the twentieth century. Individualism for James would also come to be associated with the destructive power of mental abstraction and subjective thought to enshroud human beings and blunt the force of the real. Mariners, Renegades, and Castaways situated an exceptional American character type – the frontiersman, the pioneer – within world historical forces shaping modernity. Centred on a receding industry – whaling – that appeared to face away from the modern world, Moby Dick for James unlocked its deepest meanings in relation to the rise of both Hitler and Stalin in the 1930s.48

Ahab’s quarrel – for James – is with the very mechanical and industrial civilization that has raised him up, a civilization that assaults personality as an autonomous force. James’s analysis here builds on a broader critique of industrialization traceable to nineteenth-century Romanticism, and which resurfaced in the twentieth century in the notion of personality as a force of cultural redemption.49 Ahab thus represented a perversion of the desire for meaningful action in the world. James brought together this quite human need with the totalitarian impulse for willed control, in Ahab’s case, control over an inchoate universe of vital energies.

To all these tendencies and their associated dangers – including subjectivity and megalomania – James would counterpose the crew – an ‘Anacharsis Clootz’ deputation’ crossing lines of nation, race and ethnicity. For James, only the ‘ever-present sense of community … the grace and wit and humor’ offered by the crew of the Pequod held out any chance of salvation. This shipboard community was for James proleptic, anticipating a new democratically realized global community, and a ballast – ineffectual in the end – against the despotic ambitions of Ahab.50 Ahab, ‘trained in the school of individualism’, is unable to see how his human distance from his crew was itself the product of the very system against which he rebels: a system grounded in a hierarchy of workers and authoritarian masters, in which autonomy emerges as the sole prerogative of those in command, an arid, desolate condition of isolation.51 Ahab’s stark existential choice is to organize the world he hates or to destroy it.52 In James’s view, individualism was an ideology that blocked any mediating social formation that would moderate and redirect the atomizing force of industrial production. It left its agents marooned, in a condition of social fragmentation generating spiritual despair. The lack of human association then breeds an introspective turn seeking answers in the ‘inner consciousness’. It was here – in the ‘deepest soil of Western Civilization’ – that the madness of Hitler and Stalin was nurtured.53 In James’s account, the very conditions of capitalism generate this type, whether among Nazis, or Soviet ‘administrators, executives, organizers, labor leaders, intellectuals’. Here, in the managerial excesses of ‘advanced’ societies lay the seeds of a personality type uncontained by any form of social or communal experience. For James, Ahab has become the monomaniacal haunted man he is because of his isolation from the crew of the Pequod. This form of tyranny – the product of the individual cast loose from anchoring human and social bonds – was directed at managing things and men, producing an unprecedented centralization of power. James concludes, ‘He is the most dangerous and destructive social type that has ever appeared in Western Civilization, the totalitarian type itself.’54

Acting against this power was the ‘world-federation of modern industrial workers’ that was the crew of the Pequod. In contrast with the self-consuming energies of Ahab are the three savage harpooners who remain untouched by the ‘intellectual and emotional self-torture’ from which Ahab suffers, and which propels the madness of the Pequod universe. The alternative to the hypertrophy of the self was the full realization of personality through communal action.55 Binding self and others together was a common tie to nature through the agency of tools: technologies brought to heel by their social purpose. James’s Hegelianism is here most apparent in this vision of the productive dialectic through which self – interacting with the object world – attains to full consciousness through its own objectification. It is solipsism that short circuits the realization of the self through its material relations, and for James, Ahab was the very type of the solipsist.56

7 ‘Midnight, Forecastle’, vol. 1, p. 259 (chapter 40).

Kent’s Ahab – conceived in the late 1920s, while the ‘stomach ulcer of fascism’ was still a gurgle – nonetheless prophesied unwittingly the rise of what James would label the ‘totalitarian’.57 Like James, Kent was a socialist. In this respect, the two responses to Moby Dick are branches of the same trunk. Yet there the commonalities cease. A closer examination of Kent’s ambivalent relationship to the figure of Ahab reveals his contradictory allegiances, at once to collectivism and to the romantic vision of imperial selfhood. Verging on a decade of renewed collectivism, Kent’s 1930 illustrations for Moby Dick give a surprisingly attenuated treatment of the shipboard community that drew James’s admiring analysis more than twenty years later.58 In contrast to James’s collectivist vision, Kent falls notably short in capturing the global reach of the crew, or the vivacity with which Melville evokes their social worlds. One is a Shakespearean low shipboard interlude among the sailors, who in Kent’s illustration are a grizzled and generic group that fails to capture the diverse cultures of the crew, from China and Spain to Malta, Sicily and Tahiti [7]. In this scene – chapter 39 – Melville also conjures the life-affirming erotically charged energies that unite the crew in human camaraderie against the backdrop of Ahab’s obsession and then threaten to draw them down into primordial rhythms of violence. The illustration at the head of this chapter shows the miniaturized and faceless crew in profile. Another scene of human community is the frank depiction of Queequeg in bed with Ishmael in a moment of homosocial intimacy across vast social and cultural distances (‘The Counterpane’, chapter 4). The majority of the scenes of the Pequod crew, however, frame the shipboard experience as one of isolation and confrontation with a vast impersonal natural world (‘The First Lowering’, chapter 48).59 This view of the ship experience maps the existential dread of Ahab onto his crew in a manner that suggests just how far Kent himself fell short of grasping the social basis of collectivism.

8 ‘The Symphony’, vol. 3, p. 237 (chapter 132).

Kent’s most powerful visualizations centre on Ahab, a figure whose will-driven obsessions ultimately deform and distort the element of enchantment that emanates from the watery Pacific world in which the action unfolds. It is Ahab who absorbs the bulk of Kent’s interests in the second half of the book. In the concluding image of ‘The Chase – First Day’, (chapter 133), Kent endows the doubloon – sign of Ahab’s blasphemous mission – with a sacramental aura, making of Ahab one who worships graven images, in violation of the biblical commandment. Kent captured this in the horrific image of Ahab’s skeletal face rippling in the water [8], suggesting a Melvillian understanding that nature was inherently mute, and that whatever the individual saw in it was a projection of himself.60

Attracted to the figure of Ahab, Kent overlooked such picture-worthy subjects as offered themselves throughout the book; in his illustration for ‘A Squeeze of the Hand’ (chapter 94), Kent opens with a horizontal image of a detached arm and hand squeezing globules of whale sperm, losing an opportunity to pictorialize Melville’s image of communal intimacy in which shipboard labour is transformed into a utopian dissolution of boundaries.61 That Kent chose not to translate such scenes in his illustrations is revealing of what he found most compelling in his own reading of Moby Dick.62 Raymond Bishop’s illustrations for the book, published by Albert and Boni in 1933, grant more attention to the collective labour performed by the ship’s crew, although they are somewhat more generic in appearance.63 Gripped by the riven and tortured figure of Ahab, Kent was unable to visualize the shipboard camaraderie that might have balanced the ghastly intensity of Ahab’s obsession. Kent portrays Ahab, as he appears in Moby Dick itself, alone and isolated, confronting the universe through no mediating frames except those of his own monomania, signalled by his piercing and bulging eyes – the physical attributes of a world-commanding will. Ahab remakes the world in the image of his obsession; his prophetic force as a figure of modernity is the manner in which he commands a Promethean power to overcome the gravity field of other egos through the sheer magnitude of his personality. Melville, Kent and James all grasped the implications of this form of authoritarian individualism: the peculiar charismatic power that Ahab exercises over those on board, collapsing world into self through the voiding of agency among those around him. Yet Kent’s focus on Ahab, and his debilitating and disempowering impact on his crew, reveals an attraction that balances the repellant power of Ahab’s monomania. The seeds of this attraction are in Melville’s text itself; Melville’s Ahab is at once commandingly godlike and demonic. Melville’s anatomy of the doubled Promethean impulse is the thrust of chapter 94, ‘The Chart’. This symbolic duality – both godlike and godless – is evident in Kent’s treatment of Ahab, and indeed in his own Luciferean pencil self-portrait of 1934. Kent’s emblematic image of calipers measuring the globe that concludes the chapter captures these interlocking contraries. Evoking William Blake’s image of Urizen as the god creator, the image associates this with Ahab’s blasphemous thirst for mastery of the natural world. Kent graphically imagined Ahab’s madness in a vocabulary of stark skull-like imagery, bulging eyes and contorted features. Indeed, Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience frames the three-volume Lakeside Press edition of Moby Dick, from the opening image of a youth with arm extended as he gazes out (frontispiece to volume one), to the final stylized image of a figure plummeting to darkness, Icarus-like (title page of volume three).

For Kent, the autonomous self was the primary force of resistance against the enslaving regimens of industry and of mechanized forms of labour.64 An essay by his friend Carl Zigrosser reveals this charismatic quality in the make-up of Kent, about whom he wrote that, ‘He might have been and may still become a great leader of men through his personal magnetism, his adherence to principles and his unquenchable personal vitality.’ Zigrosser pondered ‘through what arduous self-discipline [Kent] achieved such mastery over himself … Perhaps it was because from birth onwards, he has never allowed any challenge to his will to remain unanswered.’ Zigrosser goes on to describe Kent in terms that recall eugenic discourse in the decades between the wars.65 Kent – seen through Zigrosser’s eyes, emerges as the very type of the ubermensch. His public persona spoke to modernist fears of enervation and degeneracy. Kent admired Nietzsche, producing a series of drawings of Thus Spake Zarathustra, and engraving a motto in German from the book onto his fountain pen.66 He shared with Alfred Stieglitz and Marsden Hartley a deep attachment to German culture and history that placed him under suspicion in the First World War, along with shared racial biases against ‘French degeneracy’.67 Also in common with Stieglitz and Hartley, he expressed moments of aristocratic disdain for democracy, as when he wrote to Zigrosser in 1919, ‘I don’t like today.… I don’t like our Democracy which appears to me more and more clearly as the last word in brute tyranny.’ And like others similarly formed, Kent expressed a selfardour bordering on the messianic: ‘I begin to be conscious of power – of an absolute power unrelated to anything else in the world. I begin to see a purpose to it all … and to believe profoundly in my own destiny, but with a kind of wonder why it happens to be I who has been chosen to carry on for a while the cloud-hidden ideals of the race.’68 He fantasized a complete withdrawal from the present, fencing himself against intrusion to turn ‘to eternity and the Cosmos … within’.69 Energized by his trip to Alaska in 1919, he rose to dithyrambic heights: ‘I want to paint the rhythm of eternity.’70 Kent the socialist appears in such moments to be deeply divided in his loyalties, contemptuous of those weak enough to be followers, and yet seduced by the power to dominate, and by the charismatic force of his own personality.

Such a reading places Kent in strange company with the spiritual godmother of libertarianism Ayn Rand, and her character from The Fountainhead, Howard Roark. In these years, Ben Duggar linked Kent and Frank Lloyd Wright – who inspired the figure of Roark – as sharing much ‘in spirit, in philosophy’. Kent, like Wright and Roark, was trained as an architect. All three figures – real life and fictional – were given to self-mythologizing; each was marked by sententious pronouncements, truculently principled stances, and an unflinching sense of purpose. And finally, all three shared elements of what Meyer Schapiro would call – in a review of a book by Wright in 1935 – a ‘theogonic’ form of self-mystification. Reasserting the hierarchy of individual over mass, the theogonic elevated the creative self to a position of central authority, and in doing so bucked all forms of authority beyond the self – a type of ‘anti-authoritarian individualism’ with which Kent’s biographers associated him. Kent saw history through the lens of his own personality and as the product of individual actors. Lacking in his repertoire of wood engravings is any developed sphere of the social. His Blakean figural language featured low horizons, colossal figures looming above the landscape, grand vistas of mountains and starry heavens. In this symbolic world, the human element assumed cosmic dimensions.71 His lifelong friend Zigrosser wrote of Kent that, ‘Man is the hero of most of his pictures.… He stands almost alone in his use of symbolism among the artists of today.’72 Kent’s subject, however, was not man as social actor but man in his most eternal and epic form, remote from the developmental challenges presented by the social realm. Reading Kent’s Ahab through the lens of Nietzsche counterbalances James’s reading of the totalitarian bent of Ahab with a different if complementary understanding: a man, not unlike Kent himself, who was intent on remaking the world in his own image by overcoming the constraints imposed on him by nature.

Kent recorded his own theogonic moments, as when he ‘had stood in spots where I have known that I was the first white man who had ever seen that country, that I was the supreme consciousness that came to it. I have liked the thought that maybe there was no existence but in consciousness and that I was in a sense the creator of that place.’73 Kent’s robust self-mythologizing – and his theogonic attitude towards a nature he created out of his own form-giving powers – sat uneasily with his social dedication to unionization and collective action on behalf of the newly formed artists’ groups of the 1930s. Poised between his socialist commitments and his individualistic mythos, Kent was, all unknowingly, drawn to the authoritarian elements always embedded as a possibility within the double-edged figure of American monomania – a self-guided god-dethroning energy with the power to usurp and mobilize the democratic masses. Zigrosser framed the tragic dimension of Kent’s world in Nietszchean terms: ‘Man in all this mental struggle has … come to the very end of his own resources. He has discovered that he can not fly at will into the universal, but is bound down to earth by the limitation of his senses. It is a tragic but at the same time an heroic conception.’74

By the 1950s, however, the contrary terms that had occupied, sometimes uncomfortably, the same ground in the 1930s would become starkly polarized. The theogone-cum-master of the universe embodied in such charismatic public figures as Wright and Kent were now arrayed in very different colours, filtered through the language of totalitarianism, of master and slave, of autonomy and domination. Such terms expanded in the 1950s across a broad spectrum, from the liberationist radicalism of James – deeply anti-Stalinist and dedicating his energies to anti-colonial movements – to the virulently right-wing anti-communism of the US under McCarthy.

Seeping into James’s characterization of Ahab, the anti-totalitarian rhetoric of tyrants, masters and slaves was turned, in one instance, against Kent himself – steadfastly loyal to the Soviet Union.75 In 1950, Max Eastman, former socialist editor turned rabid anti-communist, published a letter to Kent asking him to explain his continued allegiance to the Soviet regime responsible for disappearing and eliminating thousands of dissident writers as ‘enemies of the people’. ‘I keep trying to think of excuses for you. Is it perhaps just a zeal to be “radical,” to be against the capitalist as of old, that constrains you to play the lackey to an infinitely more dreadful tyrant?… Is it necessary … to adore, to bend your knees to a Lord and Master after all?’76 Rising to a zealous pitch of condemnation, Eastman invoked the ‘enslavement of men’s minds and bodies to a tyrant’, asking rhetorically what unanalysed ‘demon in the Zeitgeist’ was pushing Kent to such suicidal actions, in a manner that brings to mind Ahab’s self-destructive pursuit of the phantasmal white whale.77

Kent’s contradictory behaviour and crossed loyalties are unusual only in bringing together in one individual the range of sympathies and conflicted allegiances that characterized the 1930s more broadly. Both a socialist and a profoundly self-driven individualist, his career exposes fundamental tensions in the collectivism of the 1930s: between democracy and the individual; over the role of singular charismatic figures in mass movements; and concerning the place of personality as both a model of social redemption and a force capable of capsizing mass movements through a dangerously commanding self-obsession. Neglecting the communitarian ethos just coming into focus in the early years of the 1930s, and emphasized in James’s 1953 book on Moby Dick, Kent’s Ahab captured a different dimension of the novel with prophetic power: the maniacal force of an ego-driven madman who would remake the world in his own image. Ahab’s charismatic force in bending the shipboard community to his will substituted a cult of personality for democratic communal action.

Complicating Kent’s own moral and political stance towards the authoritarian personality embodied in Ahab was the extent to which he shared aspects of Ahab’s overweening will and egoistic projections onto nature. Impelled by desires for mastery – over his own weaknesses and over those who would compromise or hedge Kent’s unyielding nature, he may have been, like Milton, ‘of the Devil’s party without knowing it’, drawn to the very qualities of Ahab that fascinated C. L. R. James while provoking his unambiguous political condemnation.78 James the anti-Stalinist and Kent – loyally pro-Soviet until the end of his life – each found in the figure of Ahab a cipher of the present. But Kent, unable to wrest himself free of his own self-mythologizing, unwittingly retraced the apotheosis of the individual that was, for James, the fatal force threatening his world.

1 Clifton Fadiman, ‘Introduction’, in Herman Melville, Moby Dick; or, The Whale (Heritage Press: New York, 1943), p. v.

2 Lakeside Press of R. R. Donnelly and Sons published a deluxe edition priced at $70.00, one of four illustrated American classics. The other three in the series were Edgar Allan Poe’s Tales; Henry David Thoreau’s Walden; and Richard Henry Dana’s Two Years Before the Mast. On the commission, see David Traxel, An American Saga: The Life and Times of Rockwell Kent (Harper and Row: New York, 1980), pp. 159, 166. The Modern Library and Random House both published a concurrent edition with 283 illustrations, a Book-of-the-Month Club selection.

3 Thayer Papers, Archives of American Art, quoted in Constance Martin, Distant Shores: The Odyssey of Rockwell Kent (Chameleon Books Inc.: Berkeley, California, 2000), p. 12; Rockwell Kent, Voyaging: Southward from the Strait of Magellan (G. P. Putnam’s Sons and Knickerbocker Press: New York and London, 1924), p. 24, quoted in Martin, Distant Shores, op. cit., p. 17; Jake Milgram Wien, Rockwell Kent: The Mythic and the Modern (Hudson Hills Press: Manchester and New York, 2005), p. 15. See also Alan Wallach, ‘Rockwell Kent’, Arts Magazine, vol. 54, no. 2 (October 1979), on Kent’s mythic landscapes, with their ‘calculated formality and deliberate emotional distance’, resulting in ‘a stylized and objective quality’ quite distinct from the expressionist language that runs through a different current of American art.

4 Bennett Cerf, At Random, as cited in Wien, Rockwell Kent, op. cit., p. 105.

5 Quoted in Elizabeth A. Schultz, Unpainted to the Last: Moby Dick and Twentieth-Century American Art (University of Kansas: Lawrence, 1995), p. 27.

6 I am most grateful to Jamie L. Jones for sharing her chapter ‘The Black Arts and the White Whale: Rockwell Kent’s Illustrations for Moby Dick’, from ‘American Whaling in Culture and Memory, 1820–1930’, unpublished PhD thesis (Program in the History of American Civilization, Harvard University, 2011).

7 Jones argues that American publishing in the 1920s deployed these older media – especially in the ‘American Classic’ series initiated by Lakeside Press – in a retrospective spirit.

8 A characteristic endeavour was the ‘Retrospective Exhibition of American Art’ in 1921, including some six hundred works of visual art, dating from 1689 up to the present. This was purportedly the first such retrospective ever given to American art, an overlooked moment of cultural self-construction that opened the way for many more such exhibitions featuring a range of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century arts, as well as for the grand inventories of the Federal Art Project (Index of American Design). See Wien, Rockwell Kent, op cit., p. 61.

9 Quoted in Schultz, Unpainted to the Last, op cit., p. 28.

10 In a letter to William Kittredge, 11 November 1926, quoted in Wien, Rockwell Kent, op. cit., p. 134.

11 Rockwell Kent, How I Make a Woodcut, from the series Enjoy Your Museum (Esto Publishing Company: Pasadena, 1934).

12 Lewis Mumford, Herman Melville (Literary Guild of America: New York, 1929), p. 160.

13 This more nuanced reading is already apparent in Clifton Fadiman’s 1943 commentary, in which he uses such terms as ‘chiaroscuro’: ‘the symbolic values of the book are not allegorically plain, as in The Pilgrim’s Progress’. Fadiman, ‘Introduction’, op. cit., p. ix.

14 See Wien, Rockwell Kent, op. cit., p. 50.

15 Mumford, Herman Melville, op. cit., p. 161.

16 Nick Selby (ed.), Herman Melville: Moby Dick (Columbia University Press: New York, 1998), pp. 8, 15.

17 D. H. Lawrence, Studies in Classic American Literature (T. Seltzer: New York, 1923/1973), p. 153.

18 Ibid., p. 145.

19 Ibid., pp. 160, 159, 146.

20 Mumford, Herman Melville, op. cit., p. 181.

21 Ibid., p. 171.

22 Ibid., pp. 4, 5.

23 Lawrence’s Studies in Classic American Literature and William Carlos Williams’s In the American Grain are among the best known and most probing of these efforts, although they point in quite different directions. In 1943, Clifton Fadiman identified the adventurous readers of Moby Dick in the twentieth century as the ‘lucky Balboas and Columbuses who … rediscovered its Pacific rhythms and Atlantic rages’. Fadiman, ‘Introduction’, op. cit., p. v.

24 Allegory reads surface narrative or meaning in relation to a deeper subtextual meaning that is stable and contains the key that unlocks whatever internal significance resides in the surface. Surface and depth in allegory are hierarchically arranged as levels of truth; the manner in which surface and depth mutually animate one another in symbolist modes of meaning is flattened out in this more emblematic expression.

25 That Melville was aware of Ahab’s symbolic castration and its effects on Ahab is evident from the chapter ‘Ahab’s Leg’, in which he writes that ‘Ahab did at times give careful heed to the condition of that dead bone upon which he partly stood.’

26 ‘Ahab, Fallen in Nantucket’, in chapter 106, ‘Ahab’s Leg’, vol. 3, p. 122.

27 Schultz, Unpainted to the Last, op. cit., p. 32, gives a similar, though less explicit, reading of this image.

28 Typical of this self-mythologizing is this from Wilderness: ‘We came to this new land, a boy and a man, entirely on a dreamer’s search; having had vision of a Northern Paradise, we came to find it.’ Rockwell Kent, Wilderness: A Journal of Quiet Adventure in Alaska (Wesleyan University Press and University Press of New England: Hanover, New Hampshire, and London, 1996), p. 3.

29 According to Michele Bogart, Artists, Advertising, and the Borders of Art (University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 1995), p. 245, Kent joined the Socialist Party in 1904. See Traxel, An American Saga, op. cit., p. 43. See also Frances Pohl, ‘Rockwell Kent and the Vermont Marble Workers’ Strike’, Archives of American Art Journal, vol. 29 (1989), pp. 150–60; and Matthew Baigell and Julia Williams (eds.), Artists Against War and Fascism: Papers of the First American Artists’ Congress (Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, 1986).

30 See Rockwell Kent, published by the American Artists’ Group in 1945.

31 In 1952, Kent would write to a correspondant that he ‘had the honor of having introduced Melville to the Soviet people’. Traxel, American Saga, op. cit., p. 206.

32 Kent’s contempt for the working classes was phrased in Nietzschean rhetoric of ‘slavish self-abasement’; see Traxel, American Saga, op. cit. p. 176; Alan Wallach, ‘Rockwell Kent’, op. cit., p. 15, recalls hearing Kent in his later years making a speech ‘which had as its theme, and frequent refrain, “Thank God for the Soviet Union!”’

33 See Arthur Sabin, Red Scare in Court: New York Versus the International Workers Order (University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, 1993), p. 253.

34 Kent apparently wished to join the party but was advised against it on the grounds that he was more valuable working outside the party (presumably because his membership might erode his appeal to a broad public). Personal correspondance with Andrew Hemingway.

35 Rockwell Kent, It’s Me, O Lord: The Autobiography of Rockwell Kent (Da Capo Press: New York, 1955).

36 Kent’s cultural notoriety in the decades between the wars was nourished by the books he published of his exploits in the arctic and subarctic wilderness, and his daily exposure to danger. These published adventures in turn promoted other artistic enterprises in such widely varied spheres as advertising, lecturing, political activism and fine-arts exhibitions. Small wonder then that Kent – apparently without any saving irony – would incorporate himself, becoming a marketable entity in which the strands of charismatic personality, a recognizable and easily imitated style, and wilderness adventure would conjoin in a self-reinforcing product: ‘Rockwell Kent, Inc.’ See Merle Armitage, Rockwell Kent (Alfred Knopf: New York, 1932), p. 4.

37 Carl Zigrosser, ‘Rockwell Kent’, Print Collector’s Quarterly, 25 April 1938, p. 141.

38 Jamie L. Jones notes one other striking affinity associating Kent with Ahab, in her chapter on Kent’s illustrations of Moby Dick: writing about the illustration at the head of chapter 36 (‘The Quarter-Deck’, vol. 1, p. 236), she notes the manner in which Ahab’s ivory leg cuts into the deck, like an engraving tool: ‘This image … offer(s) a strong characterization of Ahab that concisely links the mad captain with his navigational powers and with Kent’s own woodcutting practice.’ Jones, ‘The Black Arts and the White Whale: Rockwell Kent’s Illustrations for Moby Dick’, op. cit., pp. 5–6.

39 His biographer Merle Armitage referred, for instance, to ‘the suffocating effects of our lip-stick civilization’. Armitage, Rockwell Kent, op. cit., p. 42.

40 See Christopher Wilk, Modernism: Designing a New World: 1914–1939 (V & A Publications: London, 2006); Klaus Theweleit, Male Fantasies (University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, 1987).

41 Armitage, Rockwell Kent, op. cit., p. 24.

42 The phrase is from C. L. R. James, from Mariners, Renegades, and Castaways: The Story of Herman Melville and the World We Live In (Bewick Editions: Detroit, 1978), p. 55.

43 Stark Young, ‘The World of Rockwell Kent’, New Republic, vol. 50, no. 648 (4 May 1927), p. 302. This view was echoed in a passage quoted by Armitage, Rockwell Kent, op. cit., p. 41: ‘Everything is done by pure intention and perfect values and no dependence for effect is placed upon accidents or surface appearance of paint.’

44 Kent’s commitment to the craft of wood engraving was acknowledged as unusual – a quality that – ‘much out of fashion’ and ‘reactionary’ – marked his departure from the spurious effects of ‘broken color, exaggerated impasto’, and ‘surface appearance’ that marked the school of Paris with which Kent was favourably compared by his defenders. Merle, Rockwell Kent, op. cit., p. 41. In addition, Kent rejected the modern hierarchy of the arts, blurring the lines between printmaking, fine arts and advertising. He drew a distinction, however, between artists working in advertising while maintaining their autonomy, and artists doing commercial art entirely driven by the needs of the patron. See Bogart, Artists, Advertising, and the Borders of Art, op. cit., pp. 243–55; also ‘There is no such thing as commercial art: A letter from Rockwell Kent’, Professional Art Quarterly, vol. 2, no. 4 (Summer 1936), pp. 6–7.

45 This is most apparent in chapter 87, ‘The Grand Armada’.

46 James was not alone in associating Ahab with Hitler; Fadiman, ‘Introduction’, op. cit., p. vi, indirectly linked them as well.

47 James, Mariners, Renegades, and Castaways, op. cit., p. 8.

48 James’s most explicit statement of this theme is in Mariners, Renegades, and Castaways, op. cit., p. 60, in which he identified Melville’s primary theme as ‘how the society of free individualism would give birth to totalitarianism’.

49 See here Casey Nelson Blake, Beloved Community: The Cultural Criticism of Randolph Bourne, Van Wyck Brooks, Waldo Frank, and Lewis Mumford (University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill, 1990).

50 James, Mariners, Renegades, and Castaways, op. cit., pp. 71, 53.

51 Ibid., p. 8.

52 Ibid., p. 50.

53 Ibid., pp. 10, 31.

54 Ibid., pp. 5, 12.

55 Here however it should be pointed out that James’s vision of collectivism exceeded that of Melville himself; the crew of the Pequod in truth is fully implicated in Ahab’s maniacal quest, drawn – with the exception of Starbuck – into his obsessive vision by the sheer force of magnetic personality.

56 James, Mariners, Renegades, and Castaways, op. cit., pp. 19–20, 32.

57 The phrase is Stuart Davis’s in ‘The New York American Scene in Art’, Art Front, February 1935.

58 One possible reason for the virtual absence of scenes of the crew is that the full-page illustrations were vertical in orientation, making it quite challenging to conceive a composition of multiple figures that would fit the format.

59 See for instance ‘Knights and Squires’, p. 171; ‘Dusk’, p. 244; ‘The First Lowering’, p. 325; and ‘The Spirit Spout’, p. 339.

60 The theme of Narcissus in Kent’s work is interesting in this regard. See his wood engraving ‘Forest Pool’, which reprises the Narcissus theme.

61 ‘I squeezed that sperm till a strange sort of insanity came over me; and I found myself unwittingly squeezing my co-laborers’ hands in it, mistaking their hands for the gentle globules. Such an abounding, affectionate, friendly, loving feeling did this avocation beget; that at last I was continually squeezing their hands and looking up into their eyes sentimentally … let us all squeeze ourselves into each other; let us squeeze ourselves universally into the very milk and sperm of kindness.’ On the ambiguity of Kent’s version of Ahab, see Schultz, Unpainted to the Last, op. cit., p. 35.

62 Kent served as president of the International Workers Order (IWO), founded in 1930, a multinational federation formed out of immigrant Jewish subcultures to serve the mutual aid and insurance needs of workers, and comprised of communists and socialists. He would articulate a vision of multiculturalism at the heart of the IWO: ‘more like a tapestry, woven of brilliant colored threads, every one of which can be distinguished and keep its own characteristics’. Given these sympathies, and his own argument with the melting-pot vision of American assimilation, it is noteworthy that Kent did not pick up on the theme in Moby Dick, to which James had responded so forcefully two decades later. The quote appears in Sabin, Red Scare in Court, op. cit., p. 252; on Kent and the IWO, see Sabin, pp. 249–66 and passim.

63 See for instance ‘Men at Try-Works’.

64 On Kent’s frontier mythos, see Wallach, ‘Rockwell Kent’, op. cit.; also Kent, Wilderness, op. cit.: ‘To sail uncharted waters and follow virgin shores – what a life for men!’

65 In Zigrosser’s words, Kent was impatient ‘with weakness, sickness, and the neurotic temperament in general. Enjoying superb health and vitality, he cannot understand a state of sickness. Having disciplined his faculties to the control of will, he cannot tolerate vacillation or irresolution.… His is a highly objectified art, clean, athletic, sometimes almost austere and cold.’ Zigrosser, ‘Rockwell Kent’, op. cit., p. 151.

66 ‘Zarathustra and his Playmates’ (1919: brush and ink, Morgan Library); Kent also had Wagnerian moments, as when he described the northern lights of Greenland as like ‘a glorified Isolde’s veil; and where the breath of her desire touched it, it grew hot and bright’ (Salamina). Armitage, Rockwell Kent, op. cit., p. 44, humorously imagined his ascension to Valhalla. On the enormous impact of Nietzsche in the US, see Jennifer Ratner-Rosenhagen, American Nietzsche: A History of an Icon and His Ideas (University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 2012). The book traces the scope of Nietzsche’s reception, which spanned the political spectrum, from Emma Goldman to Ayn Rand.

67 Traxel, An American Saga, op. cit., p. 121.

68 Quoted in ibid., p. 111. Kent’s contempt shaded into eugenic language, as when he dismissed the ‘physically deformed, slouch-gaited, dull-eyed, dead-souled’ people he encountered in Vermont. Kent also invoked ‘knightly ideals’ from the age of chivalry for his children; see Traxel, An American Saga, op. cit., pp. 124–5.

69 Quoted in ibid., p. 108.

70 Ibid., p. 117.

71 Characteristic of this is his woodcut ‘Workers of the World Unite!’ – a heroic nearly nude man with a spade lunging out against an unseen bayoneted army against a toylike industrial backdrop.

72 Zigrosser, ‘Rockwell Kent’, op. cit., p. 151.

73 Ibid., p. 149.

74 Ibid., p. 153.

75 This at least is the assertion made by Traxel, An American Saga, op. cit., p. 178.

76 Max Eastman, ‘An Open Letter to Rockwell Kent’, Plain Talk, vol. 4, no. 7 (April 1950), p. 45.

77 Ibid., p. 41.

78 Melville may also have been of the devil’s party, sharing with Kent moments of theogonic self-inflation in which he assumed divine powers. He famously wrote to Nathaniel Hawthorne that the secret motto of Moby Dick was ‘Ego non baptizo te in nomine patris, sed in nomine diaboli!’ My thanks go to David Blake for this connection.