‘RED HASHAR’

LOUIS LOZOWICK’S LITHOGRAPHS OF SOVIET TAJIKISTAN

In April 1931, Louis Lozowick travelled to the new republic of Tajikistan in Central Asia, the lone visual artist among a group from the International Union of Revolutionary Writers (hereafter IURW).1 During his stay in the country, he made sketchbook drawings that he subsequently developed into lithographs, which appeared in magazines and exhibitions over the next few years, constituting a portfolio of images of sovietization in action at the peripheries of the Soviet Union.2 His travelling companions formed a ‘Writers Brigade’ that included the veteran Austrian journalist Egon Erwin Kisch, the Frenchman Paul Vaillant-Couturier, editor of the communist newspaper L’Humanité, the Polish modernist writer Bruno Jasieński, the Norwegian journalist Otto Liuhn, and Joshua Kunitz, a fellow American and an editor of the magazine New Masses.3 A revolving cast of Communist Party officials guided the travellers eastwards through the steppes towards Central Asia, extolling the marvels of sovietization in their particular localities in highly selective itineraries that avoided scenes of hardship or suppression. The Writers Brigade detailed this extensive journey in numerous publications that typify the communist subgenre of travel writing by mixing observation with propagandist affirmation.4

Arriving in the mountainous Tajikistan, the writers conflated the epic transformations of sovietization with the rich history and dramatic landscape of the region. Lozowick enthused in Theatre Arts Monthly:

Here in the pathway of the Sassanian kings, Alexander the Great, Genghis Khan, and Tamerlane, the radical changes brought by the Soviet have been greater than in the Soviet Union as a whole: from the wooden plow and the tiny individual plot to the latest agricultural machinery and collective farming; from polygamy and child marriage to complete equality of the sexes.5

Lozowick’s lithographs betray a touristic fascination with this outer reach of the USSR, and while purporting to describe sovietization, they idealize the process and exoticize the setting. These images, writes Andrew Hemingway, ‘suggest a magical transformation in a picturesque environment rather than a desperately poor Muslim region being wrenched into the twentieth century’.6

Rather than simply detailing sovietization, Lozowick’s affirmative vignettes are redolent of the propagandist ritual of ‘red hashar’. Lozowick explained ‘red hashar’ by describing a procession in the city of Kurgan Tiube:

Tajiks in colourful costumes, turbans, kerchiefs, astride diminutive donkeys and all singing in a chorus. Musicians played the drums and pipes and dancers headed the procession. The riders carried red flags with inscriptions: ‘Soviet Cotton for Soviet Factories’, ‘Cotton Independence for U.S.S.R.’ etc. The whole thing had the festive air of a wedding ceremony or a celebration of some holiday. It was a procession I was to see in all parts of the country, ‘red hashar’, representing an old Tajik custom of mutual aid, of helping a neighbour behind in his field work; and it was a good illustration of the way in which the Soviet system utilizes old customs and institutions by transforming them to meet new needs.7

‘Red hashar’ was a performative representation of sovietization, a means of reframing potentially anti-Soviet Tajik traditional culture in a pageant of collective enterprise. If sovietization indicated the rapid modernization, collectivization and partial secularization of a society defined by residual feudalism, religious dogmatism, rigid gender hierarchies, and traditionalism in culture, while bypassing both the development of capitalism and the revolutionary event, then ‘red hashar’ epitomized the attempt to justify these dramatic changes through cultural rituals. Insisting upon harmonious redirection rather than disruption was crucial because these changes were controversial. Martha B. Olcott writes:

The Soviet takeover in Central Asia was a political, economic, and social revolution. The Bolsheviks called for the immediate nationalization of all land, including the waqf (clerically owned) lands; an action which threatened the power of the traditional leaders. The Soviet authorities in Tashkent introduced anti-religious legislation which outlawed Koran schools and closed all Shari’a (religious) courts. The social tensions implicit in these unprecedented actions were exacerbated by the previous isolation of Central Asia from even the most moderate ideas.8

Olcott explains that the Soviet state aimed to ‘sculpt its citizenry in an ideal image’.9 Bringing Tajikistan into pace with the Bolshevik tempo involved the supplication of the old to the new, and ‘red hashar’ thus connoted obeisance, or enforced cooperation, to imposed transformations. ‘Red hashar’ licensed the continuation of traditional pastimes, such as equine sports, to contain Tajiks who might resist sovietization by joining the Basmachi (a derogatory term meaning ‘brigands’), a movement that violently opposed religious, land and gender reform. ‘Red hashar’ therefore balanced precariously between appeal to cooperation and forcible insistence.

Lozowick does not represent the Basmachi or any apparent obstacles to sovietization in his lithographs, which mark his most directly pro-communist subject matter. Yet despite the celebratory tone and consequent ideological glossing, they repeatedly show disparities between new and old with mild comic overtones, thus implying an incongruous nexus of Soviet and Tajik social orders. This is especially apparent in his representations of Tajik men, whose opposition to sovietization often constituted the old violently rejecting the new. In stylistic terms, his treatment of the images appears conflicted, mixing together modernist and outmoded techniques to produce an unstable but tendentious modernism. Lozowick mediates between his characteristic spatial arrangements, developed in the early 1920s in response to European avant-garde tendencies, and more traditional modes of description, marking his greatest adherence to conventional figuration yet retaining aspects of his prior innovations, as if seeking a bespoke visual idiom to communicate this troubled meeting of old and new.

1 Louis Lozowick, Tanks #2, 1929, lithograph, 37. 3 × 22.7 cm. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase. Copyright © 1929 Lee Lozowick.

In some respects, Lozowick’s images are consistent with a gradual shift in his output from the schematic depictions of cities and machines with which he made his name during the previous decade to a politically engaged mode that emphasized the social determinates of industry and urbanism [1].10 For Virginia Hagelstein Marquardt and Barbara Zabel, this turn towards a more literal and socially contingent mode emphasized the worker’s role in constructing machines and buildings to suit the transformations brought by the Great Depression. In opposition to Marquardt and Zabel, Hemingway complicates this narrative by questioning the degree to which Lozowick’s Precisionist machine aesthetic was essentially an American version of Constructivism predicated on technological optimism that gave way to social realism, and argues that his late 1920s figurative work was thematically nuanced and formally complex, borrowing compositionally from radical formalist photographic perspectives while asserting the continued importance of graphic art.11 His representations of New York during this time offer a vision of an alienated capitalist metropolis that was more coterminous with the disconcerting ‘magic realism’ of Neue Sachlichkeit, with its residual faith in art, than the technophile, propagative ethos of Constructivism. In 1930, Lozowick wrote a short article on lithography in which he derided the polarities of ‘ornamental abstraction’ and ‘photographic actualism’ in favour of a medium that retained crafted qualities but witnessed the conversion of three-dimensional form through ‘the grainy surface of the stone’ into textural and tonal surfaces, into a post-abstract figurative art.12 Furthermore, lithography as a medium bestrode the old and the new, with its prior innovativeness now an outmoded technology, yet suits this curious hybrid of residual gallery art with a type of visual travel reporting-cum-propaganda. Superficially, the propagandist agenda underscoring his Tajikistan images might necessitate an abandonment of such critical potential, in that sovietized societies were purportedly non-alienated. Yet in these juxtapositions of old and new, Lozowick struggles to represent the Tajik as a worker, and suggests the alien nature of proletarianism in a hitherto feudal social order.

Perhaps the Tajikistan images witness Lozowick’s ambivalent response to the communist debates about proletarianism at the turn of the 1930s, in which his work was strongly censured. Indeed, he was grudgingly caught up in the wave of cultural proletarianism through his involvement with the John Reed Clubs and New Masses. In New Masses in 1929, Pauline Zutringer claimed that Lozowick’s ‘machine art is bourgeois’ because it glorified capitalist objects at the cost of the proletarian, a crude argument that he batted away as ‘unsolicited heroicization of the worker’ in a terse riposte printed below the article.13 Under the editorship of Mike Gold, New Masses interpreted the broad policies of the ‘Third Period line’, which distinguished communist parties from other leftist and especially social democratic political movements, to call for proletarian consciousness in opposition to a somewhat reductive model of bourgeois culture. Gold, Kunitz and several members of the communist milieu travelled to Kharkov for the Second World Plenum of the International Bureau of Revolutionary Literature in November 1930, and found that such proletarianism was not a rigid cultural policy.14 Nevertheless, Lozowick made an awkward attempt to validate his practice in an article entitled ‘Art in the Service of the Proletariat’ in Literature of the World Revolution in 1931, with an optimistic statement that revolutionary artists ‘have profited by the experiments of the last twenty-five years … [and] utilize the laconic clear-cut precision of certain younger artists’.15 However, the following year Anne Elistratova, in International Literature (the new title of Literature of the World Revolution), harshly demonized Lozowick’s machine art as a ‘repudiation of the revolutionary class struggle’ in an extensive critique of New Masses’ riven cultural policy and ineffectual response to the Depression. Elistratova provided a more serious version of the ‘machine art is bourgeois’ thesis:

Lozowick depicts the process of production as devoid of personality and of human traits; the human factor in the class relations under the system of production escapes the field of his artistic vision. By showing the might of technique ‘in general’, outside of its class content, of technique per se, Lozowick falls into a fetishization of capitalist technique.16

The degree to which this public dressing down in International Literature influenced Lozowick in his coeval development of the Tajikistan lithographs is uncertain, although the almost exclusive focus on the ‘human factor’ of the citizens of this emergent republic is telling. Certainly, when the images appeared in International Literature the following year, they may have restored some faith in the political consonance of Lozowick’s art with the IURW. Paradoxically, having reluctantly measured his machine art against a confused model of proletarianism, Lozowick’s Tajikistan images depict a region where both machines and proletarians were in short supply, and capitalism was as alien a concept as communism. Here they encountered a world far from the proletariat’s industrial metropolitan locus, and a populace that was not predisposed towards proletarianism.

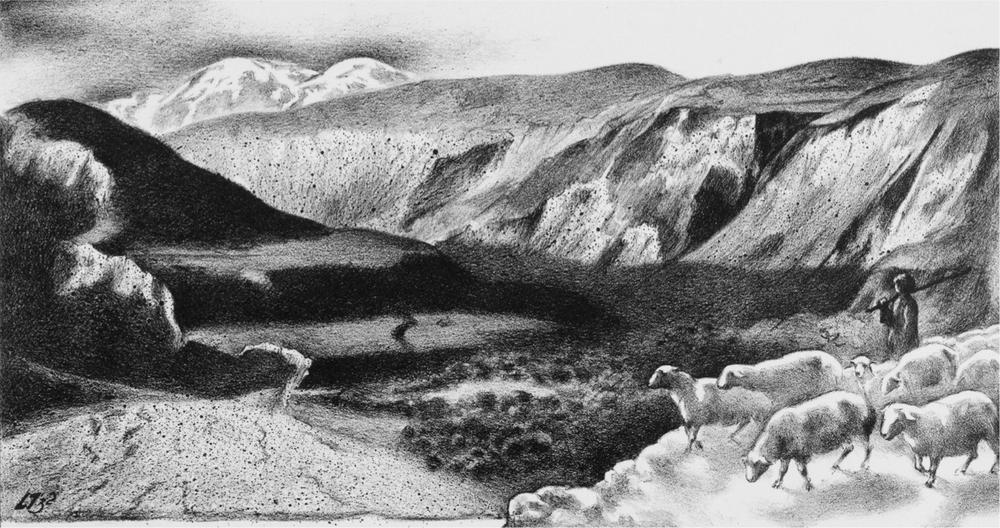

2 Louis Lozowick, At the Gates of Pamir, 1932, lithograph, 13.5 × 25.4 cm. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Adele Lozowick. Copyright © 1932 Lee Lozowick.

The overriding theme of the accounts by the group was the epic encounter of old and new in a dramatic environment. Tajikistan is predominantly made up of the mountainous topography of the Pamir Highlands, an outgrowth of the Hindu Kush, with a smaller area of flatlands in the Ferghana Valley around the capital Dushambe (renamed Stalinabad in 1931; now Dushanbe). In a New Masses piece of November 1931, which featured the first appearance in print of Lozowick’s images, a set of four loosely rendered sketchbook drawings, Kunitz writes that Tajikistan ‘is primitive, wild. Here and there one discovers traces of civilization: now a green patch of cultivated land rising on a steep incline – a triumph of human persistence and ingenuity; now an ethereally woven bridge suspended perilously over the angry, roaring Dushambe’.17 Although not illustrating this text, Lozowick’s representation of the precarious ‘Devil’s Bridge, Tajikistan’ depicts a lone Tajik on a donkey cautiously progressing over a rickety structure high above a wild river that curls with an almost rococo flourish. In Kunitz’s ‘Red Roads in Central Asia’ from the August 1932 issue of Travel, a photograph of the bridge has a caption citing the structure as proof of the necessity of modern bridges for road systems, whereas Lozowick’s image does not have such purposeful anchorage, but merely displays aesthetic and touristic delight in this antiquated scene. In his bucolic lithograph At the Gates of the Pamir [2], Lozowick shows a Tajik shepherd blithely guiding his flock along a ridge overlooking a dazzling mountain panorama in a scene that strongly invokes romantic landscape paintings (it is worth noting that following the Tajikistan trip, Lozowick visited Yosemite National Park, joining a long lineage of American landscape artists, from Albert Bierstadt to Ansel Adams, who marvelled at this paradisiacal environment). Indeed, technical experimentation is entirely absent in this image, as if modernism is somehow ill equipped to communicate the grandeur and timelessness of a scene where modernity is almost an antithetical phenomenon. When the image appeared in International Literature, with the subtitle ‘Taking Sheep to Pasture’, it perhaps served as contextual scenery for other images showing sovietization’s achievements, such as ‘Pioneers Going to School’ and ‘Native Volunteers of the Red Army’. However, when used to illustrate Kunitz’s ‘Soviet Asia Sings’ in New Masses in April 1935, the lithograph acquired the caption ‘Sheep Collective – Tajikistan’, which might seem fanciful but is loosely credible, inasmuch as Vaillant-Couturier describes the party resting at the mountain collective farm of Kahalla in the Pamir borders.18 There is, however, a definite slippage in these images from the narrative of sovietization into generic Grand Tour wonderment at Tajikistan’s sublime vistas.

In Free Soviet Tadjikistan, Vaillant-Couturier recalls a conversation at Tashkent station when a guide called Marussya warned the embarking party: ‘Beware of romance and the picturesque.’19 As the written accounts and Lozowick’s images demonstrate, forsaking romantic, exoticizing tropes when conveying the particularity of Tajikistan’s topography was not easy. Such touristic marvelling at the republic’s natural beauty and atavistic customs offended the group’s Tajik communist guide. Kunitz relays that as the car rumbled through mountain passes, Vaillant-Couturier waxed lyrical about the passing scenery, thus aggravating Isai Khodsaiev, a member of the Tajik State Planning Commission, ‘a veritable dynamo, a typical Bolshevik’ and an unambiguous champion of the new.20 Kunitz quotes his plea:

If you ever write about Tadjikistan … please don’t fall into the error of most of our Russian literary comrades who visit us, don’t descend to exoticism, don’t become worked up over the magnificence of chaos … the quaintness of our apparel, the mystery hidden beyond our women’s paranjas (veils), the charm of sitting on rugs under shady plane trees and listening to the sweet monotone of our bards, of drinking green tea from a piala and eating pilaf with your hands.21

Although Kunitz states that he replied that a smattering of exoticism would enliven the reportage and might encourage curiosity among American readers who had scant knowledge of the republic, he concurs with Khodsaiev’s insistence that the Writers Brigade should highlight the achievements of sovietization, such as new irrigation systems, educational facilities, improvements in sanitations, advances in cotton farming, numerous inroads against religious intransigence, and the liberation of women.22

Lozowick’s lithographs address many of these details of sovietization, but I will focus primarily on images that witness the more controversial aspects – of which the most contentious issue was the unveiling of Tajik women. Lozowick’s images of veiled and unveiled women illustrate Kunitz’s 1935 two-part ‘New Women in Old Asia’ article in New Masses about the liberation of women. Kunitz relays women’s conditions through the harrowing story of Khoziat Markulanova, the organizer of a village Women’s Department, who experienced the forced wearing of a paranja from childhood and an unwanted arranged marriage. The new Soviet authorities facilitated Khoziat’s escape from effective slavery, and provided her sanctuary and an education in Tashkent.23 For the Soviets, the paranja symbolized the status of the Tajik woman as a chattel, liable to be married before puberty, sold, swapped, constrained or beaten – a situation sustained by Adat and Shari’a (common and religious laws, respectively).24 Gregory J. Mansell terms Central Asian Muslim women ‘the surrogate proletariat’ through which ‘intense conflicts could be engendered in society and leverage provided for its disintegration and subsequent reconstitution’.25 While too cautious to outlaw the paranja for fear of a mass rebellion, the Soviets launched ‘a campaign to promote unveiling [that] culminated in the hujum (onslaught) of 1927, in which thousands of women tore off and burned their veils in public squares’, a performative display that heralded reforms for women and girls such as the banning of polygamy and marriage under the age of sixteen, and the granting of equal legal status and divorce rights.26 As Marianne Kemp writes, in reference to neighbouring Uzbekistan:

Unveiling became a ritual act that had both personal and political significance for the women who chose to unveil, and who persuaded others to do so. In these public unveiling shows, identity with the state was performative, and gender subversion was a declaration of loyalty to the state and the Communist Party. Of the many thousands of women who rejected the norms of Central Asian urban Muslim culture by suddenly revealing their faces in public, hundreds were murdered between 1927 and 1929. The unveilings, and the social backlash that unveilings stirred, were the crucible within which women became Uzbek citizens.27

The origins of these policies lay in the Muslim Jadid movement, which formed an ‘uneasy collaboration with the Soviet regime’ and provided the personnel for the local membership of the Communist Party.28 Adrienne Edgar writes that it is easy to simplify a Soviet-Central Asian opposition: ‘One should be careful not to overstate the distinction between “alien” Soviet rulers and the “indigenous” leaders of Muslim nation-states. The Soviet state and party apparatus in Central Asia included indigenous communists who rhetorically and even enthusiastically supported female emancipation.’29 However, many aggrieved Tajik men opposed these measures with extreme violence. Lozowick writes that a husband publicly murdered his actor wife on stage in Stalinabad, and recounts how, under orders of Fuzail Maksum, the Basmachi lynched four unveiled women teachers in Garm.30 If, as Lozowick notes, such events became subjects for literal theatrical productions, then the imposed enlightenment manifested in public unveiling and its brutal responses were symbolic gestures in a contest about control, a performative counterpart to ‘red hashar’ that was incipiently divisive.31

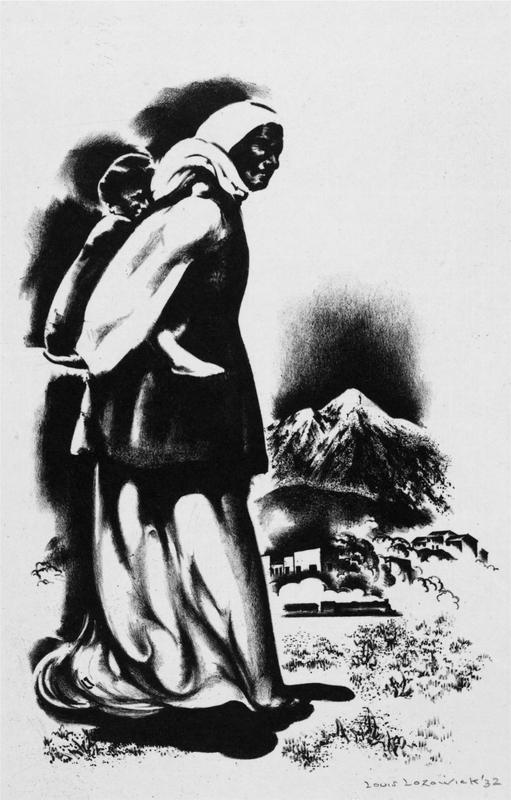

3 Louis Lozowick, Woman Unveiled, Tajikistan, 1932, lithograph, 21 × 14.5 cm. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Adele Lozowick. Copyright © 1932 Lee Lozowick.

For the Writers Brigade, the paranja was the repulsive emblem of reactionary Tajik tendencies, but despite condemning sexual inequality, their accounts were disparaging and unsympathetic towards the veiled women. Vaillant-Couturier wrote harshly that ‘the moving object which looks like a shapeless bundle set on a pair of feet is a woman, wearing her horsehair mask. This woman is the symbol of resistance to socialism, a perambulating conception of private property, of stark ignorance and religious bigotry.’32 He shows no interest in the agency, identity or even substance of the woman herself but, like the other writers, conflates the unpleasant odour of the veil with malign intransigence against sovietization. In an equally condemnatory manner, Kunitz discusses veiled women as ‘strangely amorphous, ghostlike creatures that glide, silent and mysterious through the narrowly-winding, deserted alleys of any Central Asian town or village … these are the women of Central Asia, vestiges of a remote past, living corpses eternally imprisoned in their coffins’.33 Lozowick’s Woman in Veil, Tajikistan shows such a figure, a spectral form consisting of dark shapes against a forbidding background of a high village on a mountain with steep, jagged inclines where a goat stands on a precipice (the figure of the woman is an adaption of one of the sketches that accompany Kunitz’s ‘Soviet Tadjikistan’ article, with an added landscape setting that dramatizes the paranja). Here Lozowick’s marks are abrasive, with large areas of shadow contributing to a jarring, ominous atmosphere.

The counterpoint to this image appears on the following page of Kunitz’s ‘New Women in Old Asia’ as Woman Unveiled, Tajikistan, and is similarly a development from a sketchbook drawing featured in the ‘Soviet Tadjikistan’ article. Whereas Lozowick frames the tiny veiled figure in an eerie scene, the unveiled women and child dominate an airy and calm landscape [3]. Here, Lozowick’s smooth, measured handling shapes an optimistic image of the Soviet liberation of women. Through unveiling, the figure becomes embodied as a woman – the act of revelation gives her both consciousness and physical substance. Indeed, Kunitz’s statement that ‘it is generally the adventurous, daring, and, naturally enough rather good-looking woman who flings aside her paranja’ is indicative of an equation of enlightenment and natural sexuality in the Writers Brigade accounts, which often comment upon the attractiveness of female Party officials.34 Illuminated by dazzling light, this graceful Soviet Madonna, with delicately drawn features and an affixed infant, strolls in a serene landscape, where in the distance a train passes by a modern conurbation nestled beneath a softly rendered mountain. If the mountain goat in Woman in Veil, Tajikistan perhaps symbolizes (male) native reaction, then here the train heralds the modern collective equality of sovietization. Indeed the ‘red train’ was a staple motif of communist culture (Vaillant-Couturier’s 1922 collection of poems was entitled Trains Rouges) from the early years of the Bolshevik Revolution, with its fêted propaganda trains, to Viktor Turin’s 1929 documentary Turksib about the construction of the Turkestan–Siberia railway, from which Tajikistan’s newly built railway line branched. The ‘red train’ and the enlightened liberated mother move in symbiotic progress. The combination of light, space and order presents sovietization as a cleansing as well as enlightening process, as if the removal of the odour of the paranja eradicated the murk of mysticism (Kunitz notes how part of Khoziat’s recuperation involved the donation of clean clothes and underwear).35 Yet it is notable that the unveiled woman’s sovietization manifests in motherhood, and therefore domestic work, rather than activity in the workplace, and ultimately proletarian consciousness. She is perhaps not a fully realized Soviet subject, but a conduit to, or carrier of, sovietization’s future. If there is a progression in Lozowick’s lithographs in Kunitz’s ‘New Women in Old Asia’ from veiled darkness to unveiled illumination, then the ensuing image of a ludicrously joyous boy and an unveiled girl travelling on a donkey entitled Pioneers on Way to School, Tajikistan (dressed in a similar manner to the students in Vaillant-Couturier’s photograph of Samarkand Workers’ Faculty) concludes the liberation of women from the yoke of tradition and expresses optimism for both sexes of the next generation.36

Yet while Tajik women and children could gain significantly from sovietization, their independence came at the expense of a traditional Muslim patriarchy characterized by proverbs such as ‘there is only one God in this world; [but] for a women there are two: God and her husband’ or ‘just as the shepherd may cut the throat of any of his herd’s sheep, so is the husband entitled to dispose of his wife’s life’.37 Sovietization catalysed a profound crisis for the male Tajik, involving a loss of rank, and restitution was sought with ferocity, often in the form of violence against women or members of the regime via the Basmachi, who represented, alongside restorative political ends and increasingly unrealistic military aims, a desperate bid to recapture a lost warrior identity. Lozowick’s images of Tajik men do not use the narrative device of progressive enlightenment. In the context of Kunitz’s ‘New Women in Old Asia’, the scenes of male Tajik culture, which follow the process of unveiling, juxtapose old and new, suggesting an encounter of tradition with modernity rather than a development. Each of these images depicts traditionally dressed Tajiks men engaging with facets of sovietization, such as political propaganda, technology and collectivization.

4 Louis Lozowick, Red Tea House, Tajikistan, 1932, lithograph, 25.4 × 27.6 cm. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Adele Lozowick. Copyright © 1932 Lee Lozowick.

One of the manifestations of ‘red hashar’ in Tajikistan was the appropriation and redefinition of existing customs, religious centres and social forums to instil the alien ideas of the new regime in the local culture [4]. In Red Tea House, Tajikistan, Lozowick shows the sovietized version of the traditional male Tajik meeting centre. He notes that ‘in ancient tea-houses … cloaked and bearded story-tellers squat cross-legged on the floor [discussing] industrialization, collectivization, emancipation of women, liquidation of illiteracy’.38 As if illuminated by stage lighting, three men partake of chai while a fourth plucks a regional string instrument called a dutar beneath a generic propaganda piece with workers striding forward holding aloft a torch and a poster of Lenin, which states ‘Zinda Bod Rohi Lenin’ (meaning ‘Rohi Lenin for ever!’) in reference to the Tajik town where Lozowick presumably witnessed this scene. Like the slogans at the ‘red hashar’ parade, the Soviet posters permeate sovietization into their everyday lives. The Tajiks appear placid in their tea ritual, and comfortably familiar with the posters. Two of the men, one of whom is a village elder, face the viewer as if posing for a photograph, and the passivity of the group contrasts with the striding Bolsheviks on the wall and Lenin’s focused expression. Lozowick does not rigidly demarcate the walls and the floor, and the figures hover in a spatially dislocated realm, a transcendent zone of leisure where traditional music and communist slogans seemingly coexist in a ‘red hashar’ tableau. Yet the disparity of Lenin and the marching figures with the nonchalant tea drinkers is almost comical, indicating two strikingly separate realities more than a logical relationship.

5 Louis Lozowick, Airport, Tajikistan, 1932, lithograph, 22 × 18.4 cm. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Adele Lozowick. Copyright © 1932 Lee Lozowick.

The contrast of sovietization and traditional Tajik society is more pronounced in Airport, Tajikistan, where a Soviet aviator cheerfully tinkers with his plane, amused at a lackadaisical Tajik shading himself beneath the fuselage, as if the aircraft was merely an elaborate sun awning [5]. Sitting squat in profile, his loose attire, turban and beard contrast with the aviator’s sleek, modern appearance. In the distance, another Tajik gazes at a large van driving away from the airfield. The Tajiks seem primitive and passive, as if oblivious to or entranced by technology, while the aviator looks towards the viewer to share an affectionate conspiratorial joke. Kisch’s description of the arrival of Soviet officials in Dushambe, before the name change to Stalinabad, matches the jocular tone of Lozowick’s image: ‘Here the stages of evolution are curiously jumbled. The airplane, which dropped out of the clouds and alighted in Dushambe with the members of the Government, was the first vehicle seen in this part of the world. There was great astonishment, but, since birds can fly, why not human beings?’39 Kunitz takes up this theme to describe the unfamiliarity of Soviet technology in a land where some of ‘the inhabitants have never seen a wheel. The story is told that when some bandits saw an automobile advancing along the recently built road, they thought it was a devil and, panic-stricken, scurried off into the mountains’.40 The new transport technologies brought the Soviet tempo to Central Asia, but invariably highlighted different temporalities – Lozowick describes how ‘airplanes go from Stalinabad both east and west. Automobiles, busses, trucks whizz by the leisurely camels and donkeys.’41 If the plane, the train and the automobile signified sovietization, then few Tajiks had access to such vehicles but rather depended on beasts of burden for transport; Kunitz recalls how the president of Tajikistan referred to donkeys as ‘our dear little Fords’.42 The Writers Brigade accounts all cite the airport in Stalinabad, with its fleet of twenty-eight planes, as a key symbol of sovietization, alongside the electric power station, railway station, cinema, restaurants and City Park.43 Despite these constructions, photographs support the travellers’ descriptions of the shanty-town qualities of Stalinabad, which was in a rudimentary phase of development with basic housing and infrastructure.44 However, its state of dilapidation was due – they largely neglect to add – to the Soviet obliteration of the city in the campaign against the Basmachi. The name change from Dushambe to Stalinabad was the symbolic marker of the Soviet sacking of the city, which was assisted by aerial bombardment, perhaps even from the plane depicted by Lozowick.45

6 Louis Lozowick, Collective Farmer, 1932, lithograph, 17.1 × 15.7 cm. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Adele Lozowick. Copyright © 1932 Lee Lozowick.

In contrast to these two scenes of leisure, Collective Farmer shows a working Tajik in command of a machine [6]. He drives a mighty tractor across a vast field of a collective farm, most likely cultivating cotton, which was the region’s most valuable crop. His face registers steely determination for the huge task of collectivization, underscored by two distant tractors that mark out the scale of the field. As this tractor (or ‘full-track crawler’, to be precise) is steered by belts rather than a wheel, he seems to control the machine by reins as if riding a horse or camel. Removed from his customary transport, he appears incongruous and awkward, and constrained in the cramped composition, with its photographic close-up and oblique viewpoint.46 Dominating the image, the tractor recalls one of Lozowick’s early ‘Machine Ornament’ drawings, witnessing the artist reviving his machine-aesthetic techniques to convey the mechanization integral to sovietization. At the 1935 Weyhe Gallery exhibition, the image was entitled ‘Tractor, Tajikistan’, reflecting the predominance of the machine. In Central Asia, the tractor was imbued with significance beyond its agricultural functions, serving mutual ritual and practical functions such as providing wedding or funeral transport (Kisch shows a photograph of a tractor-drawn funeral).47 The tractor was important in rationalizing farming, but also showed the benefits of modernization in a practical way and was therefore a powerful symbol of sovietization.48 Kunitz wrote that the tractor was the machine that best communicated the transformative power of the revolution to the Tajiks: ‘the moment the poor peasant discovered that working the soil with a tractor was easier, better, cheaper, faster than struggling with an omach (primitive plough), he became excellent potential material for a kolkhoz (collective farm)’.49 Machine and Tractor Stations were the organizational centres for collectivization throughout the Soviet Union, providing each kolkhoz with tractors, repairs, fuel, training and meetings, and were workplace hubs just as the red tea houses were leisure forums. Kunitz muses, ‘Is it surprising that one of the Bolshevik slogans in Central Asia was “the enemy of the tractor is our class enemy?”’50 A photograph of a row of tractors parked outside the Emir’s palace in Bukhara, now the Machine and Tractor Station of a cotton-growing collective farm, demonstrates the potent Soviet symbolism of the tractor.51 The Basmachi frequently attacked the stations to undermine sovietization but also as symbolic targets.

Therefore, the tractor was not a sufficient bulwark against opponents of sovietization, but a site of the contest between equine and mechanical cultures. The Soviets used more momentous means of ensuring control over Tajikistan. Botakoz Kassymbekova recounts that the Soviet authorities engaged in social engineering in an attempt to secure collectivization, moving five thousand households between 1925 and 1928 from Tajik sedentary groups from the mountainous Pamirs to replace Uzbek nomadic tribes in the Ferghana Valley. She writes that ‘human movement was central to the process of territorial production in early Soviet Tajikistan: human bodies were being used, quite literally, to secure and territorialize space’.52 In other words, the tractor driver in Lozowick’s image might even be a displaced migrant, grappling with an alien environment as well as new technological farming methods and collective organization (due to minimal roads and long winters when parts of the country were entirely cut off from one another, there was little internal migration before the Soviets imposed such demographic movements). Apart from using forced resettlement to create a stable farming populace, Kassymbekova argues that Soviets also sought to guarantee border security against raids from the Basmachi out of their bases in neighbouring Afghanistan.

As the accounts by the Writers Brigade relay, the swansong of the Basmachi coincided with the trip to Tajikistan, in a revival of violence that persisted until the capture and execution of the leader Ibrahim Bek in June 1931 and continued sporadically until 1934. If the Basmachi were diminished in size from the Civil War years, then military sorties led by Maksum and Bek between 1929 and 1931 compensated with ferocity by destroying railways, burning down collective farms, attacking Machine and Tractor Stations and demolishing tractors, and massacring communist officials, pro-Soviet Tajiks, and women activists and teachers. The Red Army responded with a ‘scorched-earth campaign’ across Central Asia, and during 1929 deported 270,000 Turkestanis, destroyed four cities (Andidzhan, Namangan, Marghelan and Dushambe), and razed 1,200 villages.53 In April 1931, Bek led a final expedition of a thousand troops from Afghanistan into Tajikistan and ‘with all the fury of a jihad, or holy war … implemented a large-scale programme of mass terror’.54 The campaign was heralded by sermonizing from mullahs, and further publicized in a widely disseminated manifesto that claimed affiliation with the League of Nations, insisted that unveiling ‘converted women into prostitutes’, denounced collectivization and tractors, demonized Soviet rule as ‘satanic’, and concluded that ‘this treacherous and horrid government deprives subjects of the rights to be masters of their wives and property’.55 Despite such targeted propaganda, Bek failed to gain enough support among a populace who correctly doubted his chance of victory against the Red Army, and in June was arrested and subsequently executed. The Writers Brigade was camped outside Stalinabad as the plane transporting the captured leader circled victoriously over the city.56

The Basmachi mobilized anti-Soviet sentiment by asserting traditional religious values, gender relations and property rights, and represented a violent revival of male warrior culture in the face of sovietization. Given that the Basmachi had no uniform, there was no discernible visual dissimilarity between them and other rural Central Asians. Vaillant-Couturier recalled seeing a group of men on a station platform near Tashkent: ‘The first of the men carried a revolver at the hip, the last a rifle behind his back. That was all the difference I could at first detect between them and the five others.’57 The guard were transporting the Basmachi prisoners to Stalinabad, most likely for rehabilitation as proletarians. Vaillant-Couturier later encountered some apparently successful examples: ‘These men had fought against socialist construction. Now they also took part in it as shock-brigade workers! Communism had raised these ex-bandits to the dignity of workingmen.’58

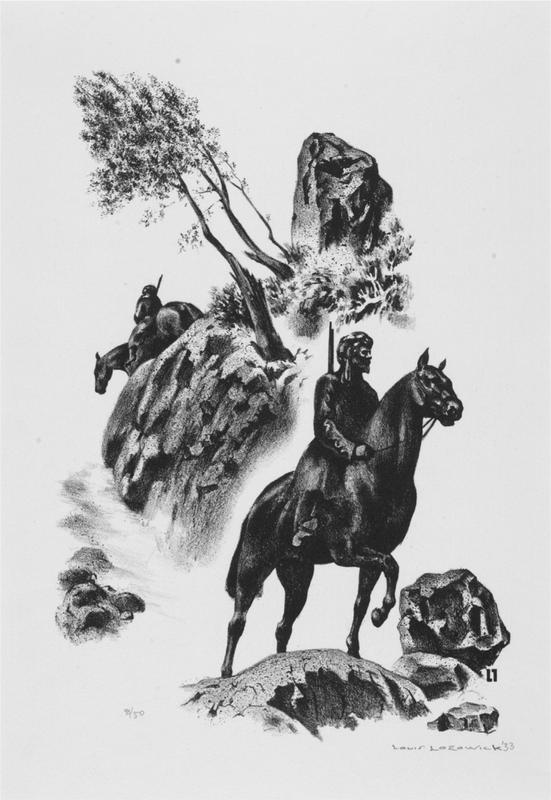

7 Louis Lozowick, Border Guards, 1932, lithograph, 26.6 × 18 cm. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Adele Lozowick. Copyright © 1932 Lee Lozowick.

The government also recruited Tajik men, including former Basmachi, to guard the borders of Tajikistan, and these soldiers were known colloquially as ‘Red Sticks’.59 Charles Shaw notes that ‘although locals may have joined up with the Red Army out of a calculus of personal safety, their willingness to take up arms was celebrated as proof of the congealing of Soviet society’.60 Lozowick’s lithograph Border Guards, or ‘Native Volunteers of the Red Army (Tadjikistan)’ (as entitled in the International Literature suite), shows two Red Sticks on horseback on a winding mountain track [7]. The foreground figure has the noble authority of an equestrian statue on an improvised plinth, a representational sculpture whose magical presence marks the border and is analogous to the framing boulders, being metaphorically tough, durable and natural in the landscape. His great coat is an important detail that signifies a uniform, as in all other respects Basmachi soldiers similarly wore turbans, rode horses and carried rifles. Despite the dense rockiness of the backdrop, the image is light and elegant, due to the predominance of blank space, the economy of the details, the delicate tonal modelling and the slightly askew perspective, which is a schematic ordering that retains the decentring and angular perspective of his earlier work. The image is carefully constructed – the protagonist is mirrored by the second soldier, whose steep descent conveys the precarious nature of the environment – and amalgamates his erstwhile technique of radical spatial realignment with the iconography, handling and compositional relationships of more traditional pictorial idioms, as if seeking a composite argot, a ‘post-Cubist’ picturesque, to connote sovietization’s melding of old and new.

The figures function as ciphers of the extensive policing of the Soviet Union’s outer limits for, as Shaw states, ‘the border was a sacred space in Soviet culture’.61 The authorities needed local volunteers with specialist knowledge of the area but also reliability and loyalty, a tricky balance that nominally depended on cooperation but in practice was guaranteed by money or coercion. Shaw writes that ‘the Soviet border project was unusually ambitious because the “us” – or the new Soviet person in the border-guard uniform and the kolkhoz dungarees – was in a constant, self-conscious process of creation’.62 In Lozowick’s image, the Red Sticks are new Soviet citizens mobilized against the Basmachi, manifesting recuperated warrior rites now reframed as the means of defending sovietization. The border of Tajikistan and Afghanistan was one of the most important frontiers in the Soviet Union, and the Red Sticks were crucial to its success in guarding against the Basmachi but also in keeping Tajiks from fleeing from collectivization.63 The Red Sticks therefore policed both sides of a porous border, and served as symbolic markers of the military power that accompanied sovietization, and the transformation of the resistant Tajik into an enforcer of the new regime. Only in this liminal performance, does the male Tajik find his Soviet substance, yet his agency is as agent of the ruling Soviet order; not quite the colonial policeman, but an example of native voluntarism, he is an allegory of the Soviet Union crystallizing at its indeterminate margins.

Soon after the arrest of Bek, the Writers Brigade attended a Red Sticks festival in the mountains, which involved dancing, songs and storytelling, and the martial-arts sport of goshten (a Tajik version of ju-jitsu). At another Red Sticks event in the Pamirs, the group witnessed the frenzied equine sport of ‘goat-ripping’, essentially a high-speed free-for-all polo for fifty players on horseback with a handheld goat carcass instead of mallets and a ball. Taking place on mountainsides with intricate rules but also considerable violence, ‘goat-ripping’ often incurred injuries and sometimes fatalities of man or horse. As Lozowick details in his 1933 Travel article ‘Hazardous Sport in Tajikistan’:

This brutal game has been forbidden by the Soviet Government, because of its danger to the lives of men and animals and because it interferes with the people’s regular occupations. It’s impossible to keep them on the job when the game is played in their neighbourhood. Nevertheless, in spite of the ban, local authorities in the more isolated centres occasionally permit the sport as a concession to one of the old customs which is not particularly dangerous to the new social order.64

Lozowick’s lithograph of two goat-ripping players, on anatomically suspect horses in a whirl of movement, contrasts with his representation of the heroic border guards. He conveys the dynamism of the sport in a friezelike figural arrangement in which one player attempts to steal the goat in a primal melée of men and animals. He writes that ‘obviously “goat-ripping” is a heritage of an ancient time – when the goat was a common zoomorphic symbol of many people in many lands’.65 Goat-ripping involved a sanctioned venting of traditional warrior rites, an opportunity for performing horsemanship skills within the confines of a legitimized Soviet event that concluded with fireside songs, music and stories about defeating the Basmachi. On the borders of Tajikistan, the authorities permitted the Tajik a moment of licensed combative expression in the form of traditional sports, contained within the frame of a ‘red hashar’ ritual that circumscribed the limits of his new Soviet being, allowing a release of primal antic energies followed by pacified participation in sovietized storytelling.

The collision of old and new in Tajikistan is ubiquitous to the point of platitude in the Writers Brigade accounts, as these foreign communists sought to explain the necessary revisionism of sovietization while expressing touristic yearning for elements of the disappearing society. The fascination of visitors with the old world of Central Asia was widespread, evident in Lozowick’s almost rueful statement that:

Much of this legacy from the past is merely exotica, according to the crusading Soviet. It can serve no definite purpose in the new order and therefore is not worth retaining, except in the form of records. Such amusements are being registered, collected, photographed before they are gone and forgotten. In all parts of the country one meets composers taking down folk-songs, poets collecting folk-lore, philologists and archaeologists.66

In an unpublished account about Samarkand’s architecture, Lozowick details with lyrical intricacy the rich varieties of styles relating to the sedimented history of this ancient city without reference to sovietization except a brief mention of the new regime’s commitment to conservation of historic monuments (although he does not mention the cities obliterated by the Red Army in the purge of the Basmachi).67 Perhaps he felt it his task to provide pictorial documents of the customs and everyday scenes of traditional life that he witnessed, alongside recording the triumphs of sovietization. As Mikhail Kalatosov’s astonishing 1930 documentary film Salt for Svenetia shows, the Soviets often expressed profound fascination with the strange ancient rites of the indigenous people that they were remaking as new citizens. Certainly, Lozowick’s images echo the selectiveness and paternalism of anthropological documentary – for instance, could a Tajik shading under an aeroplane ever be a comrade, let alone a proletarian, rather than an object of study, an ‘other’?

Lozowick was admiring of ethnographic studies of the region. In reporting on the marginal Jews of Central Asia for the Menorah Journal, he fêted a regional museum where an ethnographic display demonstrated Soviet archival collation of the plants, animals and people of the area, and a photographic exhibit of ‘Racial Types of Central Asian Jews’ featured a legend that noted how by avoiding intermixing ‘the Jews of Central Asia have retained their racial type in greater purity than the Arabs’.68 He also marvelled at ‘old photographs of Bokhara Jews’ in the Central Asiatic Library, which had the ‘straightforwardness and simplicity of early daguerreotypes’.69 These archival traces of the dwindling Jews captivated him, but he also searched for signs of extant Jewish life. In Stalinabad, despite being told this was the only world capital with no synagogue, he found one, which was ‘very primitive, hardly to be distinguished from the surrounding flat-roofed clay huts’, but was informed that it was ‘soon to be converted into a workers’ club’ because all the young Jews had migrated to the collective farms.70 The text does not evince anxiety (his writing style was hardly emotive and this was a piece for the travel section of the magazine), and yet Lozowick’s account details a narrative of Jewish diminishment due to sovietization that borders on nostalgic. It is worth recalling that his leftism was rooted in those encounters with anti-Semitism that had originally caused him to emigrate from Imperial Russia, and his engagement with Russian art, culture and society bore traces of his experience as a specifically Jewish exile, displaced in the diasporic flight from pogroms.71 Drawn to past, present and future in Tajikistan, Lozowick witnessed temporal disjuncture that manifested pertinently in the scattered remains of the vanishing Jewish population.

‘Red hashar’ aimed for mutual harmony, but the process of sovietization was really a severe collision of old and new. Kunitz’s enthuses:

Central Asia is in a paroxysm of change. The immemorial droning of the somnolent East is drowned out by the strains of the Internationale mingled with the sirens of new factories and the hum of American and Soviet motors.… For years now Central Asia has been a medley of clashing values. The revolution has unleashed a whirlwind of passion. The old fights back, desperately, brutally. But the new is triumphantly advancing. Even those who cling to the old cannot resist the magnificent upsurge of the new.72

It was a violent clash, which calmed only when the Red Army crushed the Basmachi. In Lozowick’s portfolio, old and new appear in degrees of tension in style as well as content, signifying competing techniques and themes that achieve only a fictive resolution. Additionally, Lozowick’s own crisis with proletarianism found a mirror in the Tajiks who themselves were far from ready for sovietization, and his seemingly uncritical fealty veiled an acknowledgment of the difficulty of reducing his, or any, art to a unitary proletarian allegory or technique. While representing Soviet enlightenment clearly with the motif of unveiling, his images of male Tajiks incongruously encountering sovietization suggest a society in conflict. In an undated note, he recalls receiving a radio message while flying over Central Asia about a Basmachi attack, and ponders ‘Thus the Civil War in the Soviet Union was not quite over even as late as 1931.’73 While his affirmations of sovietization may contain elisions and border on misdirection, the treatment of contradictions between the old and new shows a stumbling performance of ‘red hashar’ that does not quite conceal several ongoing conflicts.

1 Tajikistan, the Tajik Soviet Socialist Republic, was founded in 1929. It was frequently spelled as ‘Tadjikistan’ in the 1930s, but I use the current official spelling except when citing a primary text. Tajikistan became an autonomous republic within Uzbekistan in 1924, before joining the USSR as the Seventh Independent Republic in 1929. Tajikistan was formerly known as Eastern Bukhara, a province of the khanate of Bukhara, presided over by the Emirs but ruled by the Tsar since annexation by Imperial Russia in the mid-1840s.

2 Lozowick’s images accompanied the following articles: Louis Lozowick, ‘Hazardous Sport in Tajikistan: the Daredevil Horsemen of Central Asia’, Travel, no. 61 (September 1933); ‘The Theatre of Turkestan’, Theatre Arts Monthly, November 1933; ‘4 Drawings from Tadjikistan by Louis Lozowick’, International Literature: Organ of the International Union of Revolutionary Writers, no. 3 (1933). His images also appeared in several pieces by Joshua Kunitz: Joshua Kunitz, ‘Soviet Tadjikistan’, New Masses, November 1931; ‘New Women in Old Asia’, New Masses, 2 October 1934; ‘New Women in Old Asia’, New Masses, 9 October 1934; ‘Soviet Asia Sings’, New Masses, 23 April 1935. The lithographs featured at the following exhibitions: ‘American Print Makers, Eighth Annual Exhibition’, Downtown Gallery, New York, 3–29 December 1934; ‘The Fifth Exhibition of American Book Illustration’, Gallery of the Architectural League, New York, 19–30 March 1935; ‘Paintings and Lithographs by Louis Lozowick’, Weyhe Gallery, New York, 6–18 April 1936.

3 The term ‘Writers Brigade’ appears in the text that accompanies Lozowick, ‘4 Drawings from Tadjikistan’, frontispiece.

4 See Egon Erwin Kisch, Changing Asia, trans. Rita Reil (Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1935; Berlin, 1932); Paul Vaillant-Couturier, Free Soviet Tadjikistan (Co-operative Publishing House of Foreign Workers in the USSR: Moscow, 1932); Joshua Kunitz, Dawn Over Samarkand: The Rebirth of Central Asia (International Publishers: New York, 1935); Bruno Jasieński, Man Changes His Skin, trans. H. G. Scott (Co-operative Publishing Society of Foreign Workers in the USSR: Moscow, 1935). There is some suggestion that Lozowick himself intended to write a book, as ‘The Fifth Exhibition of American Book Illustration’ exhibition note lists ‘three illustrations for a book on Soviet Tajikistan’. See ‘The Fifth Exhibition of American Book Illustration’, Louis Lozowick Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution (hereafter LLP), Reel 5989, Frame 860. As well as the publications listed above, Lozowick wrote ‘New World in Central Asia’, Menorah Journal, no. 20 (July 1932), which was not illustrated. He also produced two unpublished essays: ‘Soviet Frontiers’, undated manuscript, LLP, Reel 5896, Frames 471–82, and ‘The Architecture of Samarcand’ [sic], undated manuscript, LLP, Reel 5895, Frames 909–16.

5 Lozowick, ‘The Theatre of Turkestan’, op. cit., p. 887.

6 Andrew Hemingway, Artists on the Left: American Artists and the Communist Movement, 1926–1956 (Yale University Press: New Haven and London, 2002), p. 17.

7 Lozowick, ‘Soviet Frontiers’, op. cit., p. 1.

8 Martha B. Olcott, ‘The Basmachi or Freemen’s Revolt in Turkestan 1918–24’, Soviet Studies, July 1981, p. 352.

9 Adeeb Khalid, ‘Backwardness and the Quest for Civilization: Early Soviet Central Asia in Comparative Perspective’, Slavic Review, vol. 65, no. 2 (Summer 2006), p. 233.

10 Born into a shtetl in Kiev in 1892 and experiencing the anti-Semitic persecution of a pogrom in his childhood, Lozowick had fled to America in 1906 and began his career taking classes at the National Academy of Design. He travelled to the Soviet Union in 1922, chronicling its cultural developments and establishing a reputation as one of America’s foremost experts on Soviet art and culture by giving lectures, writing several important articles, and producing the essay for the first American survey of post-revolutionary developments for the Société Anonyme’s Modern Russian Art exhibition catalogue in 1925. He was closely involved in the 1927 Machine-Age Exposition, giving talks on Russian art. Lozowick produced numerous illustrations and publicity materials for New Masses. In 1930, he cemented his reputation as an expert of Soviet art with a chapter in Voices of October, a book on Soviet culture that he coauthored with Kunitz and Joseph Freeman, wrote extensively on Soviet film and theatre, and was an active member of the communist John Reed Clubs.

11 Andrew Hemingway, The Mysticism of Money: Precisionist Painting and Machine Age America (Periscope Publishing: Pittsburgh, 2013), p. 148.

12 Louis Lozowick, ‘Lithography’, Space, vol. 1, no. 2 (March 1930), reprinted in Lozowick, Survivor for a Dead Age, op. cit., pp. 286–7.

13 Pauline Zutringer and Louis Lozowick, ‘Machine Art is Bourgeois’, New Masses, February 1929, p. 31.

14 Beyond asserting dialectical materialism as the basis for proletarianism, the conference’s resolutions about style were opaque, non-proscriptive and centred on literature rather than visual art, stating in a special issue of Literature of the World Revolution that ‘we must recognize that in the overwhelming majority of cases, except for the proletarian literature of the USSR, our movement has not even begun to formulate the problems of creative method’. ‘The Results of the 2nd International Conference of Revolutionary and Proletarian Writers’, Literature of the World Revolution, 1931, p. 6.

15 Louis Lozowick, ‘Art in the Service of the Proletariat’, Literature of the World Revolution, no. 4 (1931), reprinted in Lozowick, Survivor for a Dead Age, op. cit., p. 289.

16 A. Elistratova, ‘New Masses’, International Literature, no. 1 (1932), p. 110.

17 Kunitz, ‘Soviet Tadjikistan’, op. cit., p. 12.

18 Kunitz, ‘Soviet Asia Sings’, op. cit., p. 18; Vaillant-Couturier, Free Soviet Tadjikistan, op. cit., p. 34.

19 Ibid., p. 6.

20 Kunitz, ‘Soviet Tadjikistan’, op. cit., p. 12.

21 Ibid.

22 Ibid., p. 13.

23 Kunitz, ‘New Women in Old Asia’, part one, p. 26.

24 Ibid., p. 23.

25 Gregory J. Mansell, The Surrogate Proletariat: Moslem Women and Revolutionary Strategies in Soviet Central Asia, 1919–1929 (Princeton University Press: Princeton, 1974), p. xxii.

26 Adrienne Edgar, ‘Emancipation of the Unveiled: Turkmen Women under Soviet Rule’, Russian Review, vol. 62, no. 1 (January 2003), p. 132.

27 Marianne Kemp, ‘Pilgrimage and Performance: Uzbek Women and the Imagining of Uzbekistan’, International Journal of Middle East Studies, vol. 34, no. 2 (May 2002), p. 264.

28 Adeeb Khalid, ‘Backwardness and the Quest for Civilization: Early Soviet Central Asia in Comparative Perspective’, Slavic Review, vol. 65, no. 2 (Summer 2006), p. 241. It should be noted that ‘the new’ was not an entirely Soviet introduction as many of the Tajik communists originated in the Central Asian Muslim reform movement called the Jadid (the New). The origins of the Jadid date back to the 1880s, when Ismail Gasprinski, a reformist Muslim scholar who was editor of the journal Tercümen, proposed the notion of ‘Usul-e-jadi’ (new educational principles), encouraging modernization of Central Asia via education and reconciliation of Islam with Western science. See Ahmed Rashid, ‘The Fires of Faith in Central Asia’, World Policy Journal, vol. 18, no. 1 (Spring 2001), p. 46.

29 Adrienne Edgar, ‘Bolshevism, Patriarchy, and the Nation: The Soviet “Emancipation” of Muslim Women in Pan-Islamic Perspective’, Slavic Review, vol. 65, no. 2 (Summer 2006), p. 271. Recent scholars appraise the neglected role of Jadid Muslim feminists, who remain largely unrecognized in the accounts by Soviet writers and foreign communist or fellow-traveller visitors. Furthermore, there was considerable regional variation in Central Asia in the amount of women who wore the paranja, such as in Turkmenistan where women were largely unveiled. See Edgar, ‘Emancipation of the Unveiled’, p. 132. See also Marianne Kamp, The New Woman in Uzbekistan: Islam, Modernity, and Unveiling under Communism (University of Washington Press: Seattle, 2006).

30 Lozowick, ‘Soviet Frontiers’, op. cit., p. 7. Mansell confirms that such reprisals occurred, involving the murders of many women activists, including Anna Dzhamal and Enne Kulieva, who were early Zhenotdel (the Party’s Women’s Department) members, and Hamza Hakim Zada Niyaziy, a leading Uzbek writer. Mansell, The Surrogate Proletariat, op. cit., pp. 282–3.

31 Lozowick, ‘The Theatre of Turkestan’, op. cit., p. 887.

32 Vaillant-Couturier, Free Soviet Tadjikistan, op. cit., p. 55.

33 Kunitz, ‘New Women in Old Asia’, part 1, op. cit., p. 23.

34 Kunitz, ‘New Women in Old Asia’, part 2, op. cit., p. 19; Lozowick, ‘New World in Central Asia’, op. cit., p. 169. There are some similarities with the 2004 ban on conspicuous displays of religious affiliation in French schools, which is the subject of Joan Scott’s The Politics of the Veil (Princeton University Press: Princeton, 2007). Scott argues that while masquerading as a liberatory gesture, the ban contrasts healthy Western and aberrant Muslim sexualities, p. 127.

35 Kunitz, ‘New Women in Old Asia’, part 1, op. cit., p. 26.

36 For the Writers Brigade, the expansion of education was one of the Soviet’s most tangible achievements, as within a generation an almost entirely illiterate populace had risen to 25 per cent literacy and 46 per cent of children attended schools. Vaillant-Couturier, Free Soviet Tadjikistan, op. cit., p. 17.

37 Mansell, The Surrogate Proletariat, op. cit., p. 114.

38 Lozowick, ‘The Theatre of Turkestan’, op. cit., p. 887.

39 Kisch, Changing Asia, op. cit., p. 97.

40 Joshua Kunitz, ‘Red Roads in Central Asia’, Travel, vol. 59 (August 1932), p. 7.

41 Lozowick, ‘New World in Central Asia’, op. cit., p. 170. Botakoz Kassymbekova ‘Humans as Territory: Forced Resettlement and the Making of Soviet Tajikistan, 1920–38’, Central Asian Survey, vol. 30, nos. 3–4 (September–December 2011), p. 353.

42 Kunitz, ‘Red Roads in Central Asia’, op. cit., p. 7.

43 Kunitz, Dawn over Samarkand, op. cit., pp. 242–3; Vaillant-Couturier, Free Soviet Tadjikistan, op. cit., p. 11; Kisch, Changing Asia, op. cit., p. 89.

44 Kunitz, Dawn over Samarkand, op. cit., p. 242.

45 Lozowick does mention that Dushambe was ‘destroyed in the civil war’, but does not indicate that this was a Soviet action. Lozowick, ‘New World in Central Asia’, op. cit., p. 170.

46 Hemingway discusses the correspondence of his late 1920s images of New York with ‘New Vision’, or radical formalist, photographic perspectives and subjects. Hemingway, The Mysticism of Money, op. cit., p. 136.

47 Kisch, Changing Asia, op. cit., opposite p. 154.

48 Sheila Fitzpatrick reports that in 1928 there were 33 million horses in the USSR; in 1934 there were 15 million. Fitzpatrick, Stalin’s Peasants: Resistance and Survival in the Russian Village after Collectivization (Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1994), p. 138. It was also a machine that a Tajik might well use. Kunitz notes that ‘approximately sixty per cent of the peasant population of Tadjikistan is said to have joined the collective-farm movement and the tractor is now a familiar sight in a land where the hoe and the ox were the principal methods used for tilling the soil’. Kunitz, ‘Red Roads in Central Asia’, op. cit., p. 10. Vaillant-Couturier records a conversation with Comrade Petrov, manager of the Vaksh State Farm, who relayed that of the six hundred tractor drivers who would graduate from the farm’s training school 70 per cent would be Tajik and Uzbek. Vaillant-Couturier, Free Soviet Tadjikistan, op. cit., p. 39.

49 Kunitz, Dawn Over Samarkand, op. cit., p. 205.

50 Ibid., p. 206.

51 Kisch, Changing Asia, op. cit., opposite p. 62.

52 Kassymbekova, ‘Humans as Territory’, op. cit., p. 349.

53 William S. Ritter, ‘The Final Phase in the Liquidation of Anti-Soviet Resistance in Tadzhikistan: Ibrahim Bek and the Basmachi, 1924–31’, Soviet Studies, vol. 37, no. 4 (October 1985), p. 488. In 1931, the Basmachi numbered about 2,000, whereas in the peak of the movement, c. 1922, they numbered about 18,000, although this was not a standing army but a loose network of opponents to the Soviets, but as the Red Army in Central Asia numbered 150,000 and were consistently brutal in supressing revolt (killing 50,000 at Kokand in 1918), the resistance, although damaging, was limited in scope. See Marie Broxup, ‘The Basmachi’, Central Asian Survey, vol. 2, no. 1 (June 1983), pp. 58–60.

54 Ritter, ‘The Final Phase’, op. cit., p. 490.

55 For Bek’s Manifesto of 1931, see Kisch, Changing Asia, op. cit., pp. 140–4.

56 Vaillant-Couturier, Free Soviet Tadjikistan, op. cit., p. 27.

57 Ibid., p. 8.

58 Ibid., p. 16.

59 Kisch, Changing Asia, op. cit., p. 126.

60 Charles Shaw, ‘Friendship under Lock and Key: The Soviet Central Asian Border, 1918–34’, Central Asian Survey, vol. 30, nos. 3–4 (September–December 2011), p. 337.

61 Shaw, ‘Friendship under Lock and Key’, op. cit., p. 332. Shaw relays that the Central Asian border ran for 5,484 km and was consistently short of guards, or Pogranichnye voiska (border troops).

62 Ibid., p. 333.

63 Shaw states that between 1931 and 1933, 3,153 Tajik families left the country, and in 1933 4,372 families were held at border. Eighty to eighty-five per cent were poor farmers or labourers, ‘precisely the population that was supposed to benefit most from Bolshevik rule’. The authorities suppressed information about Tajik attempts at emigration. Ibid., p. 339.

64 Lozowick, ‘Hazardous Sport in Tajikistan’, op. cit., p. 16.

65 Lozowick, ‘The Theatre of Turkestan’, op. cit., p. 886.

66 Ibid., p. 887.

67 Lozowick, ‘The Architecture of Samarcand’, op. cit., p. 10.

68 Lozowick, ‘New World in Central Asia’, op. cit., p. 167.

69 Ibid., p. 168.

70 Ibid., p. 170.

71 Hemingway, The Mysticism of Money, op. cit., p. 109. For examples of Lozowick’s writings about Jewish art and culture in the Soviet Union, see: Louis Lozowick, ‘The Art of Nathan Altmann’, Menorah Journal, February 1926; ‘Eliezer Lissitzky’, Menorah Journal, April 1926; ‘Russia’s Jewish Theatres’, Theatre Arts Monthly, June 1927; ‘The Moscow Jewish State Theatre’, Menorah Journal, May 1928.

72 Kunitz, Dawn Over Samarkand, op. cit., p. 14.

73 Louis Lozowick, ‘Note on Russia and Russian Artists’, undated note, LLP, Reel 5897, Frames 322–84.