‘If the historical process is forcing the artist to relinquish his individualist isolation and come into the arena of life problems, it may be the abstract artist who is best equipped to give vital artistic expression to such problems – because he has already learned to abandon the ivory tower in his objective approach to his materials.’ Stuart Davis, 19361

The relations between abstract painting and leftist politics during the 1930s remain problematic and understudied aspects of the development of modern art in the United States. The reasons for this neglect are both aesthetic and ideological, with postwar critical and commercial support for what was perceived as a distinctive American style of gestural abstraction paramount among them. By the late 1940s the hegemony of a putatively apolitical formalism was accompanied by widespread rejection of the socially engaged art of the previous decade as a technically and politically misguided cultural anomaly. Conventional accounts of abstraction that insist on its opposition to figuration by stressing its purity, universalism and non-objectivity continue to bedevil an understanding of the ways in which modernist technical strategies were aligned with the expression of contemporary social and political concerns.

While the dominant visual mode in the United States in the 1930s was realist, with those on the left favouring either an illustrational naturalism or a propagandistic social realism, there were some artists who were convinced that giving form to their political vision required a modernist idiom. This desire to achieve a rapprochement between modernist art and politics is perhaps most clearly and ably demonstrated by the example of Stuart Davis. Long acknowledged as one of America’s most accomplished abstract painters, he was also one of the left’s most ardent artist-activists during the years of the Great Depression. Serving as president of the Artists’ Union, an editor of its journal Art Front, and national chairman of the American Artists’ Congress Against War and Fascism, he was a tireless supporter of the economic and political rights of artists.2 But while he adhered to communist political theory throughout the 1930s and was insistent that Marxism was ‘the only scientific social viewpoint’, he did not subscribe to orthodox social-realist aesthetics of the period.3 He was unwilling to relinquish the techniques of painting developed by the School of Paris (seen by some leftist critics as ‘bourgeois’) and effectively denied that the Communist Party provided any insight on artistic matters. His refusal of communist prescriptions for cultural production as both vulgar and naive – despite his political fellow-travelling until the end of the decade when, like many leftists, he became disillusioned with Stalinism – was underpinned by the belief that both art and politics were dynamic processes that needed to respond to changes in the material world. For Davis, just as Marxism was the most progressive social and economic force within the political realm, modernism represented a historically necessary break with earlier artistic strategies. Unlike figuration, which was tied to what he regarded as a moribund world view, abstract form and colour were the most advanced tools at the artist’s disposal and thereby offered the necessary resources for engaging contemporary reality.

Davis’s approach to art and politics has proven something of a tripping point for scholars. For example, Karen Wilkin suggests that Davis ‘scrupulously separated his painting and his social activism’.4 Although, as Wilkin observes, Davis insisted that ‘good art … could not and should not serve the needs of propaganda’, the distinction she posits between his painting and his politics misses the sophistication of his thinking during the 1930s.5 One of the central issues here is that while Davis’s artistic output demonstrates a nuanced understanding of European formal developments and a commitment to a decidedly modernist visual language, he was adamant that his work be understood as ‘realist’, a position that had important political resonances and which Davis scholars have yet to take seriously.

Both ‘realism’ and ‘modernism’ are particularly unwieldy concepts and a considerable degree of terminological imprecision is commonplace. But while discussions around realism had ossified in the Soviet Union by 1934 and the influence of the Comintern ensured that it was the Soviet model of Socialist Realism that served as a benchmark for consideration, there was nevertheless opposition to the narrowness of what amounted to Moscow criteria. As Raymond Williams puts it, the category of realism remained ‘highly variable and inherently complex’, with other alternatives enunciated across the leftist cultural field.6 For Davis, an artist was not merely an observer, nor was realism simply premised upon mirroring the world. This approach reduced art to its content and ignored the significance of form and its specific basis in material reality.7 He was insistent that while ‘class consciousness must … be the guide to the value of a work of art, it is not sufficient to evaluate a painting in terms of its social ideology’; ‘its technical ideology is also involved and must be rated.’8 The art-historical habit of contrasting realism with modernism is thus especially unhelpful with respect to Davis.9 He consistently denied that the deployment of modernist devices was tantamount to an idealist art-for-art’s sake position and ardently defended his approach to painting as a species of realism grounded in the shapes, forms, spaces and colours of the observable material world. As a result, while much of his work of the 1930s exists at a considerable distance from conventional realist aesthetics (especially as formulated by communist ideologues), formalist evaluations of his art that focus solely on his savvy incorporation of modernist pictorial devices render it next to impossible to reconcile his painting with his politics and ignore his stated ambitions.

1 Stuart Davis, Composition, 1935, oil on canvas. 56.4 × 76.5 cm. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. Copyright © 2013 Estate of Stuart Davis / DACS, London / VAGA, New York.

During the 1930s many left-wing critics were sceptical of the capacity of modernism to carry socially relevant content and condemned the use of modernistic techniques as symptomatic of an irresponsible and escapist evasion of social reality aligned with individualism and apathy. Davis, however, claimed that an adherence to the formal techniques developed by artists dependent on the bourgeois art market did not compromise allegiance with the working class. As he explained, ‘A class’ culture may develop at a different rate than the society and be at [its] best as the class is decaying.’10 Modernist forms, which were tied to a more dynamic view of contemporary experience than the static and hierarchical world view epitomized by naturalist aesthetics, constituted ‘the highest product of the preceding epoch’11 and thereby needed to be preserved and extended in the creation of new social and economic relations.

2 La Corona cigar box label. Source image for Composition, 1935.

That Davis saw a direct connection between the concerns of artists and those of other workers is evident in his Composition [1], an oil on canvas painted after he was enrolled on the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project (FAP), one of several cultural initiatives established by President Roosevelt’s New Deal administration and under whose auspices Davis was employed from 1935 to 1939. The format of the painting suggests a modernist variation on the still-life genre. It features a collage of overlapping elements clustered around the middle of the canvas and set within a shallow pictorial space. Attesting to Davis’s abiding interest in mass culture, the compositional arrangement is based on a La Corona cigar box label, which pictures a classical female figure with flowing locks and robe seated in an idyllic landscape surrounded by symbols of culture, industry and agriculture [2]. While the overall layout of Composition is inspired by the La Corona label, the painting demonstrates the way in which Davis adeptly engaged the lessons of Cubism and montage to transform source materials. Central to his working method was the practice of abstracting pre-existing images and motifs and then subjecting them to processes of fragmentation, recombination and variation in placement and size. The top centre of Composition is dominated by the silhouette of a female head in three-quarter profile rendered in thick black outline. The bust, which is set against a watery blue ground and positioned beside the fluke of an anchor, recalls the figurehead of a ship. A bright-orange artist’s palette accompanied by paint brushes is situated in the middle of the canvas and is flanked by a draughtsman’s compass and square on the left; to the right is a spade, sledgehammer, ladder and oversized gear or cog resting against a schematized building, whose prominent smoke stack suggests a factory or power station. The iconography thus brings together the tools of the artist with those of industry. As Mariea Caudill Dennison has noted, this particular constellation of elements could be ‘interpreted as an assertion of the equality of all workers’ – a parity that was pivotal to Davis’s political perspective throughout the decade and was confirmed by his experiences as a WPA employee.12 For Davis, artists were skilled labourers like any other whose contributions to society were as valuable and indispensable as those of other workers.

3 Stuart Davis, Art to the people – get pink slips, 1937, gouache, traces of pencil and collage on paper, 45.4 × 60.6 cm. Private collection, Houston. Copyright © 2013 Estate of Stuart Davis / DACS, London / VAGA, New York.

While elsewhere I argue for the political import of the abstract public murals that Davis created under the FAP, during the 1930s he also executed a number of easel paintings that acknowledge contemporary politics in a less opaque fashion.13 The paintings under consideration here are unusual instances of his employing an explicitly political iconography, but it should be borne in mind that his political claims for modernist form nevertheless extended to works where such motifs do not appear and which for him were just as political. That said, his Art to the people – get pink slips of 1937 is a gouache and collage on paper that incorporates a pointed reference to the New Deal arts projects within the context of a familiar seascape [3]. The harbour and dockside paraphernalia were recurring themes for Davis, who often retreated to the New England coastal town of Gloucester, Massachusetts, during the summer months. Gloucester was both a historic colonial port on Cape Ann with a thriving fishing industry and also home to one of the oldest artists’ colonies in the US, attracting nineteenth-century landscape artists such Winslow Homer, along with numerous members of the Ashcan School, with whom Davis had trained as a student at the Robert Henri School of Art in New York from 1909 to 1913. Davis frequently reworked his Gloucester sketches, and in this instance the title of the 1937 gouache is derived from a newspaper headline that he cut out and affixed directly onto the lower right-hand corner of the composition.

The newspaper clipping stuck to the surface of Art to the people references the American practice of including a pink slip of paper in a worker’s pay envelope as notification of immediate termination or suspension of employment. Given that government funding for the arts was a temporary relief whose future was far from guaranteed and that artists on its rolls were continually under threat of layoff, Davis was acutely aware that New Deal cultural programmes had been plagued by fluctuations in funding since their inauguration. The already tentative and uncertain nature of the FAP was exacerbated in 1937 – the year Art to the people was executed – when the much-vaunted ‘New Deal recovery’ suddenly gave way to what became known as the ‘Roosevelt recession’.14 In the face of another financial downturn, it was clear to Davis that increasing pressure to reduce the level of state interventionism in the economic sphere would have direct and unwelcome ramifications in the cultural realm. As a result, not only did Davis and the Artists’ Union fiercely lobby for the continuation of the cultural projects, they also supported two liberal bills introduced to Congress in 1938 that sought to secure federal funding for the arts on a permanent basis through the establishment of a Bureau of Fine Arts. The first bill (introduced by Representative John Coffee of Washington and Senator Claude Pepper of Florida) never made it past the committee stage, while the second (introduced by Representative William Sirovich of New York) was overwhelmingly rejected in June by a vote of 195 to 35.15

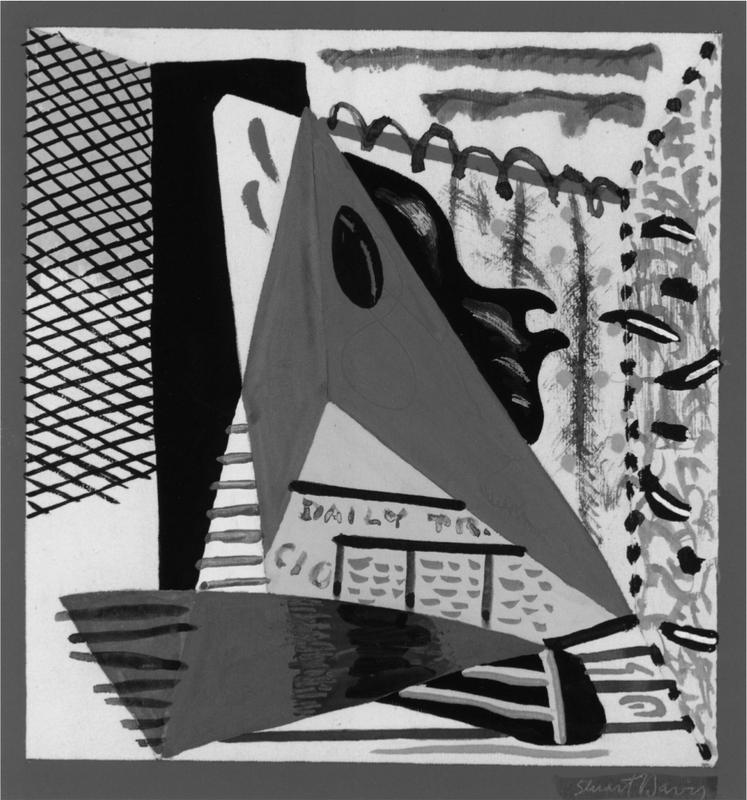

That Davis tackled contemporary political issues in the language of artistic modernism is also evident in a gouache on paper entitled Daily Tribune and CIO [4]. The predominantly abstract arrangement of shapes, patterns and textures includes a reference to the Chicago Daily Tribune, an emphatically Republican paper whose conservatism would have made it sceptical of arts projects as a New Deal boondoggle. The gouache also includes the acronym ‘CIO’ inscribed across the lower central portion of the composition. The CIO – Committee for Industrial Organization (later to become the Congress of Industrial Organizations) – was formed in November 1935 and comprised a federation of unions that advanced the principle of industrial unionism over craft unionism and competed against the corrupt and rabidly anti-communist American Federation of Labor (AFL) to organize semi- and unskilled workers on an industrial basis.16 As suggested at the outset, Davis staunchly supported the unionization of artistic workers and believed in the solidarity of all labourers. Operating under the assumption that leverage for expanding and stabilizing federal patronage would be strengthened by connecting with a broader working-class base, the Artists’ Union (with Davis as president) began courting the AFL as early as the spring of 1935, later becoming affiliated with the more progressive CIO in January 1938. The Chicago Daily Tribune was not only doggedly anti-CIO, it was also vehemently anti-communist and harshly critical of the New Deal. On 17 April 1937, the front page of the paper announced that the CIO was a ‘Red stepping stone to a Soviet U.S.’, later claiming in a headline on 10 February 1938 that a Senate Inquiry in Washington ‘Links CIO, Reds, and Roosevelt administration’.

4 Stuart Davis, Daily Tribune and CIO, c. 1936, gouache and traces of pencil on paper, 24 × 22.5 cm. Private collection. Copyright © 2013 Estate of Stuart Davis / DACS, London / VAGA, New York.

The recently published Davis catalogue raisonné dates Daily Tribune and CIO to c. 1931 on stylistic grounds, but this is impossible as the CIO was not founded until four years later. The 1967 stock list of the Downtown Gallery, which represented Davis for much of the 1930s, dates the work to c. 1936, but the explicit and unprecedented references to Chicago and the CIO make it tempting to suggest a slightly later date, namely 1937. While the painting may well have been executed earlier in the decade, Davis frequently returned to previous works to make adjustments and it is conceivable that the scrawling of ‘CIO’ and ‘Daily Trib’ on the otherwise abstract composition was linked to the Memorial Day Massacre at the South Chicago plant of Republic Steel. The incident arose as a result of Republic Steel’s efforts to break the strike called by the Steel Workers Organizing Committee of the CIO. The several thousand strikers and their supporters who gathered on 30 May 1937 to protest against restrictions on picketing were greeted with tear-gas grenades, and ten unarmed demonstrators were killed by the Chicago Police Department.17 Taking the side of industrial corporate power and the police commissioner, who denounced the episode as a communist-led provocation, the Chicago Daily Tribune supported calling in National Guard troops to reopen the mills, with the paper’s headline three weeks after the massacre victoriously stating that ‘CIO Grip on Steel Smashed’. That Daily Tribune and CIO evokes the Memorial Day Massacre is conjecture on my part, but while Davis ardently rejected the Soviet instrumentalization of art as illustrative propaganda, he nevertheless executed paintings that included tendentious references, albeit often enigmatic and oblique, to the contemporary political scene.

5 Stuart Davis, Waterfront Demonstration, 1936, gouache and traces of pencil on paper, 29.5 × 39.4 cm. Fayez Sarofim, Houston. Copyright © 2013 Estate of Stuart Davis / DACS, London / VAGA, New York.

A decidedly more clear-cut instance in which Davis engaged political issues in his work (and particularly those of labour’s rank-and-file) is Waterfront Demonstration [5], a surprisingly brutal gouache on paper that was exhibited at the ‘Waterfront Art Show’ in February 1937. The exhibition was sponsored by the communist-dominated An American Group, Inc. in association with the Marine Workers’ Committee. This was the second co-sponsored undertaking following the success of the first ‘Waterfront Art Show’ in December 1935, to which Davis also contributed a painting. The first show was mounted at the Italian Workers’ Club in Greenwich Village and included a handful of paintings and watercolours alongside a series of photographic studies by Margaret Bourke-White documenting working conditions on the New York docks. According to the communist magazine New Masses, the exhibition resulted from the revolt of a group of artists against ‘the pitying attitude of many radical intellectuals toward workers’, with many of the artists included in the show having been trained in ‘the tough three-mornings-a-week schedule of the waterfront units of the Communist Party’.18 The second exhibition in 1937 was a much a larger event that filled three floors of the New School for Social Research and was comprised of 126 works in various media by 107 artists, with a portion of the proceeds from sales going to the Marine Workers’ Committee.

During the 1930s, the New York waterfront was a focus for leftist activity, with communists exercising a considerable degree of influence by taking the lead in developing maritime unions.19 Although, as leftist author Louis Adamic pointed out in 1938, many waterfront unions already existed, most, including the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA), were ‘out and out rackets’ run by the corrupt AFL.20 However, in contradistinction to the pronounced development of radical unionism among longshoremen on the West Coast under Harry Bridges (who was closely associated with the Party and whose rank-and-file group functioned as a branch of the ILA), the same period that culminated in the ‘Big Strike’ in San Francisco in 1934 was marked by the persistence of conservative unionism in the East.21 Collective bargaining in the longshore industry in New York had long since received institutional accommodation.22 As a result, in the midst of the increased labour militancy that marked the 1930s, strike action to gain recognition was not as pressing on the East Coast as it was in the longshore industry in Pacific ports.

Although the ILA did not require the new guarantees provided for under the National Industrial Recovery Act and the Wagner Act (passed in 1933 and 1935, respectively), this alone does not explain the relative inactivity of New York maritime workers during a period when radical unionism was gaining momentum throughout the rest of the nation. More to the point was the fact that on the Atlantic coast ILA president Joseph P. Ryan was a fanatical anti-communist. By mid-decade, Ryan was sharing his convention platforms with some of America’s staunchest supporters of Hitler and Mussolini and he maintained order on the docks by employing notorious gangsters and ex-convicts as ‘union organizers’ to police the waterfront. Beginning in 1927, when he was elected to the presidency of the ILA, and continuing until 1942, when his position was ceremonially extended for life, ‘King Joe’ ensured that there was not a single union-authorized strike in the Port of New York.23 With Ryan at the helm, the early 1930s were years of extreme quiescence among maritime workers on the East Coast, and even the onset of the Depression did not trigger a significant wave of protest activity. The initiative for the formation of a new union came not from the waterfront’s rank-and-file but from the Communist Party.24 Although there already existed nuclei of communist activists on some docks, a 1936 report on ‘Problems of Party Growth in New York’ flagged up the fact that ‘more attention has to be paid by us to concentration in this industry’ and the Party was particularly keen to actively build a new union under more radical leadership.25

By mid-decade, the East Coast ILA had, according to many members, degenerated into little more than ‘a dues collection agency’ whose extensive underworld connections and corrupt collaborations with ship-owners led to the formation of ‘action committees’ throughout the port.26 By the end of 1936 two important locals had elected ‘anti-Ryan progressives’, and that autumn Bridges was invited to New York by striking East Coast seamen. Hours before he addressed a capacity crowd of 17,000 maritime workers at Madison Square Gardens, he was called to ILA headquarters, where Ryan dismissed him as the West Coast union organizer. With Ryan on the defensive, Bridges repeatedly stressed the importance of inter-coastal unity and pledged his full support to New York longshoremen if they decided to join the fight with their comrades on the Pacific’.27 When Bridges returned to the East Coast for a second time in the autumn of 1937, this time as president of the International Longshoremen and Warehousemens’ Union and affiliated with the CIO, the situation on the New York waterfront looked more promising. Representatives from eleven locals had formally endorsed the organizational principles of the CIO and the dock’s rank-and-file were now leading the anti-Ryan movement, finding themselves described by one field organizer as ‘wild and rarin’ to go’.28 Such optimism was, however, to prove short-lived. Ryan’s gunmen went to work in 1939 and physical violence (threatened and actual) effectively silenced the chorus of voices calling for reform and enforced the authority of an utterly corrupt, conservative and racketeering leadership.

During the mid-1930s, the activities of the maritime unions were well-publicized, and a number of cultural events were organized in support of their efforts, with the ‘Waterfront Art Show’ one instance in which artists were in the service of their comrades’ struggle. As Ernst Brace noted in the Magazine of Art, ‘the seaman’s strike was focusing public interest upon this aspect of city life’ and members of An American Group, Inc. wanted to take some form of ‘united action in order to demonstrate their solidarity’.29 As one might imagine, the show was lionized in the communist press, with the Sunday Worker heralding it as an event of ‘tremendous educational and social significance’ in that it was ‘the first important mass art exhibition in this country with the definite aim of supporting the rank and file of labor’.30 Leonard Sparks, the art critic for New Masses, welcomed the ‘industrial exhibition’ for enabling ‘increased contact with a broader audience’ and for endeavouring to ‘define in concrete terms the relations between art and work’.31 The Daily Worker lauded the show for demolishing ‘the old belief that artists were individuals who had no relationship to the struggles of the workers’.32 In the words of Jacob Kainen (himself a modernist painter and communist fellow-traveller with whom Davis was friendly), the exhibition unequivocally demonstrated the ‘unity between artist and worker’ by giving longshoremen an opportunity to purchase ‘art that has a real relationship to their jobs and daily life’.33

Long mistitled Artists Against War and Fascism, Davis’s contribution to the ‘Waterfront Art Show’ depicts what leftist art critic Jerome Klein described in the New York Post as ‘robot figures in police uniforms cracking down on a lone demonstrator’.34 Central to the image is a wounded protestor with a bloodied head being apprehended by two menacing figures dressed in officer’s caps and dark uniforms, one of whom wields a club or baton. Although it has been suggested that Waterfront Demonstration is ‘entirely compatible with the esthetics of social realism in that it emphasizes political message over formal experimentation’, the unusual degree of narrative coherence and pictorial transparency hardly adheres to the more legible naturalistic conventions adopted by painters within the Party’s orbit, as was noted with disappointment by communist critics at the time.35 The critic at New Masses lamented the ‘unsubstantial nature’ of Davis’s painting and seemed to find it no more useful than works that depicted longshoremen as ‘lounging bums’ or ‘beaten derelicts’, never mind the inappropriateness of images picturing ‘beautiful marine blues’ or ‘chugging tug boats’.36 Klein, who also wrote for Art Front and was a champion of social realism during the 1930s, lumped Davis in with those artists who continued to demonstrate ‘lingering tendencies toward esthetic preoccupation’. Klein disparagingly described Davis’s approach to Waterfront Demonstration as both ‘esoteric’ and ‘highly specialized,’ ultimately dismissing the gouache as ‘cryptic’.37

Waterfront Demonstration is more overtly polemical than one might expect from Davis at this juncture, which is not to say that his more abstract paintings of the 1930s were apolitical or constituted anything like a retreat into the ivory tower. Still, the gouache does not fit neatly into the category of social realism and remains more typical of his Cubist-inspired collages of the decade. A number of the elements incorporated into the composition are indecipherable, but surrounding the officers one can identify a tangle of black barbed wire; a dark cylindrical form replete with a plume of smoke that can be read as both a smoking gun barrel or a steam ship’s funnel; and an overhead wharf lamp that conjures a police interrogation room. The factory building with prominent chimney pictured in Composition reappears in the centre ground, this time with a second chimney and accompanied by a large piece of industrial machinery. The building is borrowed from Davis’s catalogue of Gloucester imagery, and while it no longer exists, historical maps suggest that it was Gloucester Electric.38 If so, the machine in front could be a rotary excavator that would have been used to move coal into the factory to generate steam power. The painting also includes a fallen placard with the word ‘LIBRE’ and a square rendered in white, yellow, red and blue that was the house flag of the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company (P&O), a British shipping company that began operating out of New York harbour in the nineteenth century. The very fact that the painting has passed for so long under the title Artists Against War and Fascism surely suggests that the overall scene and the specifics of its iconography maintain a degree of awkwardness and interpretive indeterminacy characteristic of modernist rather than social-realist practice.

Davis’s participation in the ‘Waterfront Art Show’ should be understood as a means by which he was able to support the emergent rank-and-file movement on the New York docks. Although New Masses suggests that Davis’s contribution was not immediately appreciated by the longshoremen, this would have come as no surprise to the artist.39 Prior to the advent of the arts projects, modernism had been confined to the rarefied high-art spaces of galleries and museums, places workers rarely, if ever, visited. Their lack of leisure time and limited access to art education meant that they were unfamiliar with the most recent developments in contemporary art. However, this did not mean that workers would not take pleasure from modern art or that they should be fed on a diet of popular culture and images that merely reflected their lives and experiences back to them. Subscribing to the philosophy set out by John Dewey in his influential Art as Experience of 1934 (and adopted by key figures in the New Deal Administration, including Holger Cahill, Director of the FAP), Davis maintained that what was needed was a greater democratization of culture. He was insistent that if workers were given greater exposure to modernism – something that was being achieved through federal funding for public art – they would quickly realize that they were already familiar with modernist forms. As Davis explained, these forms were directly culled from the design of contemporary objects, including ‘the shape and color of clothes, autos, cameras, airplanes, trains, cooking utensils, etc’, things that workers already knew and which in many instances they had fashioned with their own hands.40 As such, while the question of access to culture could not be separated from the larger political and economic issues of creating a more equal society, current efforts towards the democratization of art would at least enable increased access to modernism and perhaps foster increasing interest in its forms, spaces and colours.

6 Stuart Davis, The Terminal, 1937, oil on canvas, 76.4 × 101.6 cm. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. Copyright © 2013 Estate of Stuart Davis / DACS, London / VAGA, New York.

Davis’s commitment to cultivating links between artists and other workers is further demonstrated by The Terminal [6], another oil on canvas that takes the New York docks as its subject. The painting, which pictures longshoremen loading cargo, was exhibited on at least four occasions during the 1930s (including in the Whitney Museum of American Art’s ‘Annual Exhibition of Contemporary American Painting’ in 1937), thereby bringing heightened attention to activities on the waterfront. Such support for his fellow labourers was not only a crucial component of class solidarity, but also necessary if workers were to be brought on side in lobbying for permanent federal funding for the arts. As the independent leftist art historian Meyer Schapiro advised in a lecture delivered to a convention of unions from the eastern states in May 1936, although New Deal patronage constituted ‘an immense step toward a public art and the security of the artist’s profession’, the impermanence of government support meant that artists needed to make contact with a broader public if they were to secure such patronage for the future.41 According to Schapiro, whose lecture was published under the title ‘Public Use of Art’ in the autumn issue of Art Front, ‘It is necessary that the artists show their solidarity with the workers both in their support of the workers’ demands and in their art’.42 However, while Davis agreed with Schapiro on the issue of worker solidarity, their positions were marked by differences of opinion over the usefulness of the New Deal projects, and the painter did not approve of the historian’s position on aesthetics. Davis mistakenly believed Schapiro’s views on art were underpinned by a crude ‘mechanical materialism’ and criticized him as an ‘idealist’ in relation to modernism. By 1938, Davis had dismissed Schapiro as a Trotskyist, seemingly not understanding his position on modernism, which was far more refined and accommodating than Davis gave him credit for. 43

The desire to form a united front between artists and other members of the working class was not only essential to establishing a more inclusive base from which to fight for the extension of federal patronage, but also central to the Popular Front position adopted by the Communist Party at mid-decade in the fight against war and fascism. Davis was actively engaged in Popular Front activities, serving as national chairman of the New York Artists’ Congress, and his paintings of the docks coincide with the Party’s recognition that ‘more attention has to be paid by us to concentration in this industry’.44 Returning to Waterfront Demonstration, I want to argue that this painting might be understood to register differing levels of political significance simultaneously. Viewed under the title Waterfront Demonstration, and within the context of the ‘Waterfront Art Show’, it spoke to the specific experiences of marine workers and their struggle to form a new union independent of the anti-communist AFL. But the image also works with respect to a broader set of increasingly tense international issues, as is suggested by the fact that the title Artists Against War and Fascism only recently raised any eyebrows. While the iconography may be read as directly engaged with events on the docks, its date and subject matter – namely fascist goons beating a demonstrator – equally fit with the concerns of the Party and its Popular Front line. On the one hand, the multivalency of the image’s meaning is attributable to the degree of abstraction and departures from naturalism that characterizes Davis’s formal repertoire; but, on the other, the painting also points to the interconnectedness of the violent struggles of longshoremen against the fascistic leadership of Joseph Ryan and the AFL and the fighting of Popular Front soldiers abroad in the Spanish Civil War.

By 1936, the year in which Waterfront Demonstration was executed, American communists and fellow-travellers were not just battling fascism at home but also abroad. While in July, at the outbreak of war, Roosevelt declared that the US would remain neutral, events in Spain symbolized the fight against fascism worldwide, and the Comintern responded in September by launching a campaign for the formation of the International Brigades to support the Republican forces. The first group of American volunteers set sail from New York on Christmas Day. Of the more than three thousand US troops who fought in the Abraham Lincoln Battalion, a high percentage were communists, and it is estimated that more than a third were industrial workers, including steel workers, miners and a considerable contingent of longshoremen.45 With this in mind, the placard emblazoned with the Spanish word ‘LIBRE’ (free) that has been thrown to the ground could suggest that liberty has fallen, with both marine workers and the Republican army united by their struggle to overcome injustice and to overthrow a repressive regime.

Interestingly, Davis’s second gouache picturing labour struggles on the waterfront (which is known only through a contact-sheet photograph and which has been titled Waterfront Demonstration No. 2 due to its pronounced similarities to the extant painting) also prominently features a placard. While difficult to decipher, the script appears to read ‘STOP MUNITION SHIPMENTS’.46 This reading of the slogan would seem to be confirmed by a work exhibited by the Chicago-based artist Mitchell Siporin on the occasion of the New York John Reed Club’s exhibition ‘Revolutionary Front – 1934’ in the autumn of 1934. Siporin was an active member of the Club (an organization that developed out of the New Masses group in 1929 and which served as the primary institutional base for communist and fellow-travelling artists until 1935), and he was a contributor to New Masses. The work in question, which was illustrated in Kainen’s review of the ‘Revolutionary Front’ exhibition in Art Front, is entitled Stop Munition Shipments and includes an almost identical placard to the one Davis pictures in Waterfront Demonstration No. 2. While I can only speculate, such a slogan, combined with the inclusion of the flag of the P&O Shipping Co. (whose fleet not only carried passengers and mail, but since the First World War had also been involved in the transport of troops, munitions and raw materials) almost certainly refers to the sham of the non-interventionist policies in Spain enunciated by the US and other Western democracies. By 1936, the American Communist Party, its fellow-travellers – as well as many liberals and progressives – were demanding that the US cease exporting weapons and supplies to fascist aggressors, namely Germany and Japan. As such, Davis could be seen to be linking up the specific cause of the dockworkers with the Popular Front more generally. Just as his formal motifs involve a kind of condensation of elements from different aspects of contemporary experience, so too does his work manifest a condensation of distinct but interrelated political concerns.

To conclude, I also want to suggest that Davis’s inclusion of the Spanish word ‘LIBRE’ could be interpreted to have significance beyond connecting the struggles of waterfront workers with the international context of the Popular Front. While both versions of the artist’s Waterfront Demonstration are more explicitly propagandistic than much of his production in the 1930s, they are nonetheless indebted to formal techniques developed mainly by artists in Europe, and especially those associated with the School of Paris. For Davis, the deployment of such formal strategies had important political implications and he insisted they were radical in and of themselves. Moreover, in opposition to those leftists who prescribed social realism as the only art capable of engaging social and political issues in a meaningful way, he defended the artist’s right to freedom of expression (‘LIBRE’) and maintained that modernist forms were the most advanced tools at the artist’s disposal. As he stated:

The arguments used to promote ‘social content’ in art entirely fail to specify that social content expression is to be made specifically in terms of art. They stress the subject matter and state that the art form will follow from such subject matter. Such a view is misleading in that it leaves out the essential element in the process of art. In this argument, the individual does not exist, it is regimentation. It is Fascism.47

While Davis scholars usually posit a ‘striking disjunction between his paintings and his Marxist political views’, thereby leading them to assess the political and artistic aspects of his career separately, such a distinction misconstrues the sophisticated nature of his thinking on both matters.48 Despite the degree of abstraction that Davis incorporated into his painting practice during the 1930s, he conceived of his work as playing a vital and active role in the sociopolitical sphere. He was not alone in adopting this position among American artists, and serious and sustained analyses of the political character of US modernism in the interwar period would help bring the historiography of American art in line with the most advanced scholarship on European modernism.49

I would like to thank the Burlington Magazine and Art History for providing an opportunity to develop my initial thinking on Stuart Davis’s waterfront imagery. I would also like to extend my gratitude to Andrew Hemingway and Warren Carter for their thoughtful contributions to this text, and to Sarah Dunlap at the Gloucester Archives and Thomas Gordon for their generous help with identifying aspects of Davis’s iconography.

1 Stuart Davis, ‘A Medium of Two Dimensions, Art Front, vol. 1, no. 5 (May 1935), p. 6.

2 On the Artists’ Union and Art Front, see Gerald Monroe, ‘The Artists’ Union of New York’, unpublished PhD thesis (New York University, 1977). Research for Monroe’s thesis led to the publication of a number of highly useful articles on the topic, including ‘Artists as militant trade union workers during the Great Depression’, Archives of American Art Journal vol. 14 (1974), pp. 7–10; and ‘Artists on the barricades: the militant Artists’ Union treats with the New Deal’, Archives of American Art Journal, vol. 18 (1978), pp. 20–3. On the Artists’ Congress, see Matthew Baigell and Julia Williams (eds.), Artists Against War and Fascism: Papers of the First American Artists’ Congress (Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, 1986); and Andrew Hemingway, Artists on the Left: American Artists and the Communist Movement, 1926–1956 (Yale University Press: New Haven and London, 2002), pp. 123–30.

3 Stuart Davis Papers, Reel 1, 1 October 1935. Harvard Art Museum, gift of Mrs Stuart Davis. All rights reserved by the President and Fellows of Harvard College.

4 Karen Wilkin, in Ani Boyajian and Mark Rutkoski (eds.), Stuart Davis: A Catalogue Raisonné – The Complete Works of Stuart Davis, vol. 1 (Yale University Press: New Haven and London, 2007), p. 79.

5 Wilkin, in Boyajian and Rutkoski (eds.), Stuart Davis, op. cit., p. 79.

6 Raymond Williams, ‘A Lecture on Realism’, Screen, vol. 18, no. 1 (1977), p. 61. See also Williams, ‘Realism,’ Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society (Fontana: London, 1983), p. 259; and The Politics of Modernism: Against the New Conformists, ed. Tony Pinkney (Verso: London, 1989).

7 Davis, ‘Abstract Painting Today’, in Francis V. O’Connor (ed.), Art for the Millions: Essays from the 1930s by Artists and Administrators of the WPA Federal Art Project (New York Graphic Society: Greenwich, Connecticut, 1973), pp. 121–7.

8 Davis papers, 31 March 1937.

9 This simplistic polarity has not gone entirely uncontested and a handful of scholars have made much the same point; see, for example, Esther Leslie, ‘Interrupted Dialogues of Realism and Modernism: “The Fact of New Forms of Life, Already Born and Active”’, Matthew Beaumont (ed.), A Concise Companion to Realism (Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, 2010) pp. 143–59.

10 Davis papers, 10 January 1938.

11 Davis papers, 18 December 1937.

12 Mariea Caudill Dennison, ‘Stuart Davis, artists’ rights and cigars: La Corona as the source for Composition (1935)’, Burlington Magazine, vol. 150 (June 2008), pp. 472–3.

13 See Jody Patterson, ‘The Art of Swinging Left in the 1930s: Modernism, Realism, and the Politics of the Left in the Murals of Stuart Davis,’ Art History, vol. 33, no. 1 (February 2010), pp. 98–123.

14 Alan Brinkley, The End of Reform: New Deal Liberalism in Recession and War (Vintage Books: New York, 1995), p. 23.

15 On the bills, see Richard D. McKinzie, The New Deal for Artists (Princeton University Press: Princeton, 1973), pp. 151–5.

16 Boyajian and Rutkoski (eds.), Stuart Davis, op. cit., vol. 2, p. 581, n. 3.

17 George Robbins, ‘Chicago’s Memorial Day Massacre,’ New Masses, no. 23 (15 June 1937), pp. 11–12. See also David Milton, The Politics of U.S. Labor: From the Great Depression to the New Deal (Monthly Review: New York, 1982), p. 108.

18 Leonard Sparks, ‘Waterfront Art Show’, New Masses, no. 22 (16 February 1937), p. 17.

19 For a general history of waterfront activities during this period, albeit with a pronounced emphasis on the Pacific coast, see Bruce Nelson, Workers on the Waterfront: Seamen, Longshoremen, and Unionism in the 1930s (University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 1988); and Howard Kimeldorf, Reds or Rackets? The Making of Radical and Conservative Unions on the Waterfront (University of California Press: Berkeley, 1988), especially pp. 120–5 for activities in New York. For a more colourful and amusing account of the leading persona narrated by a deeply anti-communist liberal journalist, see Murray Kempton, Part of Our Time: Some Ruins and Monuments of the Thirties (1955) (New York Review of Books: New York, 1998), pp. 83–104.

20 Louis Adamic, My America (Harper: New York, 1938), p. 368.

21 On Harry Bridges, see Adamic, My America, op. cit., pp. 367–78; and Charles Larrowe, Harry Bridges: The Rise and Fall of Radical Labor in the United States (L. Hill: Westport, 1977). On the ‘Big Strike’, see Sam Darcy, ‘The San Francisco General Strike’, The Communist, vol. 13, no. 10 (October 1934), pp. 985–1004; Mike Quin, The Big Strike (Olema Publishing Company: Olema, 1949); and Nelson, Workers on the Waterfront, op. cit., pp. 127–55. See also Anthony W. Lee, Painting on the Left: Diego Rivera, Radical Politics, and San Francisco’s Public Murals (University of California Press, Berkeley, 1999), pp. 136–59.

22 For an overview of waterfront activities in the East during the 1930s, see the introduction to Vernon Jensen, Strife on the Waterfront: The Port of New York Since 1945 (Cornell University Press: Ithaca, 1974), pp. 13–35.

23 Kimeldorf, Reds or Rackets?, op. cit., p. 15.

24 See Nelson, Workers on the Waterfront, op. cit., p. 79.

25 Max Steinberg, ‘Problems of Party Growth in the New York District’, The Communist, vol. 15, no. 7 (July 1936), p. 649.

26 Kimeldorf, Red or Rackets?, op. cit., p. 122.

27 Bridges in ibid., p. 123.

28 Kimeldorf, Reds or Rackets?, op. cit., p. 124.

29 Ernst Brace ‘An American Group, Inc.’, Magazine of Art, vol. 31 (May 1938), pp. 271, 274.

30 ‘Marine Art’, Sunday Worker, 28 February 1937. On An American Group, Inc. and the ‘Waterfront Art Show’, see Hemingway, Artists on the Left, op. cit., p. 134.

31 Sparks, ‘Waterfront Art Show’, op. cit., p. 17.

32 Jacob Kainen, ‘Longshoremen are critics at waterfront art exhibit’, Daily Worker, 16 February 1937.

33 Ibid.

34 J. Klein, ‘Artists Cover the Waterfront with New Spirit’, New York Post, 20 February 1937, p. 24. While Davis gave the title Waterfront Demonstration in the exhibition, it has only recently been identified as the painting known as Artists Against War and Fascism. Stuart’s son Earl Davis titled this work many years after its completion.

35 Cécile Whiting, Antifascism in American Art (Yale University Press: New Haven and London, 1989), p. 71.

36 Sparks, ‘Waterfront Art Show,’ op. cit., p. 17.

37 Klein, ‘Artists Cover Waterfront,’ op. cit., p. 24.

38 I am grateful to Sarah Dunlap at the Gloucester Archives for her efforts to identify the building; on a 1917 Sanborn map of the area the chimney is adjacent to the words ‘Gloucester Electric.’

39 Sparks, ‘Waterfront Art Show’, op. cit. Although Sparks refers to Davis’s streetscape Coffee Pot (1931; private collection) when recounting the longshoremen’s response, Hemingway is almost certainly correct to speculate that Sparks was talking about Davis’s contribution to the 1935 ‘Waterfront Art Show’; see Hemingway, Artists on the Left, op. cit., p. 307, n. 55. For a review of the first exhibition, see Jacob Kainen, ‘Waterfront Art Show’, Daily Worker, 19 December 1935.

40 Davis papers, October 1937.

41 Meyer Schapiro, ‘The Public Use of Art’, Art Front, no. 2, November 1936, pp. 4–6, reprinted in Worldview in Painting: Art and Society (George Braziller: New York, 1999), p. 173.

42 Ibid., p. 175.

43 Davis dismissed Schapiro as a Trotskyist in his notes on 9 March 1938. He labelled Schapiro a ‘mechanical materialist’ on several occasions; see, for example, Davis papers, 27 August 1937.

44 Max Steinberg, ‘Problems of Party Growth in the New York District’, op. cit., p. 649.

45 Fraser M. Ottanelli, The Communist Party of the United States from the Depression to World War II (Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, 1991), p. 175.

46 See Jacob Kainen, ‘Revolutionary Art at the John Reed Club’, Art Front, vol. 1, no. 2 (January 1935), p. 6.

47 Davis papers, 26 June 1936.

48 Whiting, Antifascism in American Art, op. cit., p. 67, n. 12. An important exception is Patricia Hills, Stuart Davis (Harry N. Abrams in association with the National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution: New York, 1996).

49 An example of this kind of scholarship is offered by David Cottington, Cubism in the Shadow of War: The Avant-Garde and Politics in Paris 1905–1914 (Yale University Press: New Haven and London, 1998); and Cubism and Its Histories (Manchester University Press: Manchester, 2004).