Andrew Hemingway’s analysis of the role played by the communist movement in American social-realist art in his book Artists on the Left draws attention to a marked retrenchment in the postwar period of the commitments that had sustained such practice in the 1930s. With the onset of the Cold War, the US government’s campaign against leftist artists and intellectuals on the one hand and the increasing ideological rigidity of the American Communist Party on the other created circumstances that were not favourable, to say the least, for artists with ambitions to fashion art that was visibly engaged politically. Hemingway, however, does not leave the story there. He concludes with a chapter ‘Social Art in the Cold War’ in which he argues for the persistence in the postwar US art world of a figurative realism informed by politicized critical awareness – in many cases radical liberal rather than Marxist.1 He also shows how an artist such as Philip Evergood, who remained loyal to his left political convictions, continued to produce vital works that were, if largely indirectly, informed by these earlier convictions, even if he no longer enjoyed as before the support network of a political movement with whose anti-capitalist principles he could identify.2

In this essay, I build on Hemingway’s insights into the ongoing importance in the postwar period of artists’ commitment to engage with the political and social realities of the times by bringing into play the rather different situation in the European art world. In Europe, a broader diversity of politically engaged art was able to makes its mark. A significant group of high-profile artists of left-leaning or Marxist persuasion espoused a figurative mode of painting, and thought of themselves as working within an ongoing realist tradition, including such figures as the Italian communist painter Renato Guttuso and the French communist and socialist-realist André Fougeron. Complementing and contesting this tendency were the politically engaged artists who took a vanguardist stance, and who held to the view that it was only through experimenting with radical alternatives to conventional representation that their art could properly respond to the material realities of the modern world. For them, these realities did not enter into an art work by way of consciously motivated processes of depiction but through the artist’s immersion in the materiality of artistic process. Artists of more conventional realist persuasion generally took the view that such a focus on process meant giving up on the possibility of art’s conveying anything of substance about reality, and attributed to its proponents a formalistic commitment to the autonomy and non-representational nature of art to which many did not in fact adhere. In the case of an artist such as the Danish COBRA painter Asger Jorn, it was in part the compulsion actively to respond to the political realities of his times that led him to explore the representational potential of an informel painterly abstraction, a compulsion he shared with a number of anti-formalist painters working in a similar radically non-naturalistic mode.3 These included, among others, northern European artists in the COBRA group, informel abstract painters working in Italy such as Emilio Vedova, and artists associated with the Situationist International, such as the Gruppe Spur in Germany. It was in a European context, where the political climate was not so hysterically anti-communist as in the United States, and where the art world was less in the grip of the idea that modern art had to refuse direct evocation or representation (or ‘illustration’ as radical formalists would have it) of non-artistic realities, let alone any evident projection of political conviction, that the diverse nature of a politically engaged realist-inclined art in the postwar period emerged most clearly.

This chapter will concentrate on two of these figures, Guttuso and Jorn, partly because of the inherent interest of their art, but also because both were eloquent writers whose thinking brings into focus questions about artistic realism, representation and the commitment to painting as a material practice widely current in the postwar period. The first section, ‘The Two Realisms’, considers the different understandings of artistic realism and of artistic process espoused by the figurative realists on the one hand and the artists committed to a more abstracting painterly experimentation on the other. Guttuso plays a leading role here because of the breadth of his critical writing, which engages both with his own commitments to realism and with the informal abstraction that he was contesting but which he nevertheless saw as a tendency that at its best had a certain value and integrity. The second section, ‘The Materiality of the World and the Materiality of Art’, examines Jorn’s wide-ranging thinking about art and the aesthetic as material phenomena with a view to illuminating the materialist mindset informing his work as a radical practitioner of aformal painterly abstraction. The chapter concludes with brief reflections on how the figurative realists and the more politicized exponents of painterly abstraction shared certain convictions about the material basis of their art, suggesting through the configuring of their painting the complex imbrication of human agency in the impersonal forces and processes of the material world.

The Two Realisms

Renato Guttuso was a key figure for postwar realism, not only in Italy but also in Russia and elsewhere in Eastern and Western Europe. His work spoke both to those on the communist left who believed that a viable, politically engaged art needed to be based on recognizable figurative representation, and to those in the postwar artistic community who were not motivated by a left political agenda, but who like Richard Wollheim saw in Guttuso’s work a confirmation that depiction continued to be a viable option for the modern painter, against the growing critical consensus that a serious modern art should be divested of all trace of naturalistic depiction.4 More so than Fougeron, who in the immediate postwar period held a similar position in France as a politically committed communist working in a realist mode, and who made his name in the late 1940s and early 1950s as the champion of a somewhat rigid socialist realism, Guttuso played a particularly central role within contemporary European culture both as an artist and a writer on art. In his capacity as critic, he offered some of the more thoughtful reflections of the period on the political necessity of a committed realism,5 while in his art he tested the possibilities and limits of a modern, politically engaged realism that ranged from high-narrative history painting to more informal painting of modern life.

The painting that more than any other established Guttuso’s reputation as the proponent of a politically engaged realism was Occupation of Uncultivated Lands in Sicily [1], which made a considerable stir when it was exhibited at the Venice Biennale in 1950. With its strong figurative presences and ambitious scale – it is close to three and a half metres wide – it clearly offers itself up as a history painting. It was ambitious politically, as well as artistically. Popular occupation and cultivation of neglected land on the huge private estates of Sicily, contesting both the corrupt hold of the Mafia as well as that of semi-feudal landed interests on the island, was a live issue at the time over which the Italian communists and the conservative southern Christian Democrats had strongly divided.6 With its somewhat abstracting (as well as symbolic) colouring – the enlivening of the empty landscape with passages of red, green and white, echoing the tricolore of the Italian flag, as well as areas of red picking up on the colour of the communist banner raised at the head of the troop – and the formalized effect of the friezelike array of figures in the foreground, it clearly distances itself from the naturalistic norms of Zhdanovist Socialist Realism. At the same time, the individualizing of the figures and their unheroic, everyday gestures and clothing also make it very different from the classicizing Italian novecento realism of the fascist years – which incidentally is in evidence in Guttu so’s work of the earlier 1930s.

This moment represented a high point of Guttuso’s politically engaged social realism, during which he produced two other large-scale large narrative paintings concerned with the land occupation movement in Sicily and its violent suppression,7 as well as a more conventional dramatic history painting of Garibaldi and his thousand storming a bridge on their way to Palermo during his famous Sicilian campaign of 1860, which caused controversy when it was shown at the Venice Biennale in 1952.8 Guttuso himself was from Sicily and, by way of scenes situated in the south, took to depicting national political issues having to do with the Communist Party’s struggle to represent the interests of the urban and rural poor and to liberate Italy from its conservative (and fascist) past. Generally speaking, from the mid-1950s onwards, this kind of overtly political painting in a public rhetorical mode gave way to more socially orientated painting of aspects of everyday life, initially often but not exclusively proletarian9 and then in the later phase of Guttuso’s career becoming more ‘bourgeois’ and symbolic, more about his own social milieu. At the same time, he continued to produce the occasional large-scale painting addressing the public politics of the day, particularly in the politicized later 1960s and early 1970s, with, for example, Newspaper Mural – May ’68 (1968), featuring police violence against demonstrators that echoed US military violence in Vietnam, and Togliatti’s Funeral (1972), a massive allegorical work recalling the funeral of the Italian Communist Party leader Palmiro Togliatti, who had died in 1964. In the latter, Guttuso may have been claiming Lenin (featured in multiple depictions, together with a striking image of Gramsci) for an Italian Communist Party that in the early 1970s was increasingly distancing itself from the Russian Soviet party line of post-1968 retrenchment and stagnation. Then again, one needs to bear in mind that Guttuso was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize by the Soviet Union in the year he completed the painting.10

1 Renato Guttuso, Occupation of Uncultivated Lands in Sicily, 1949–50, oil on canvas, 265 × 344 cm. Stiftung Archiv der Akademie der Künste-Kunstsammlung, Berlin.

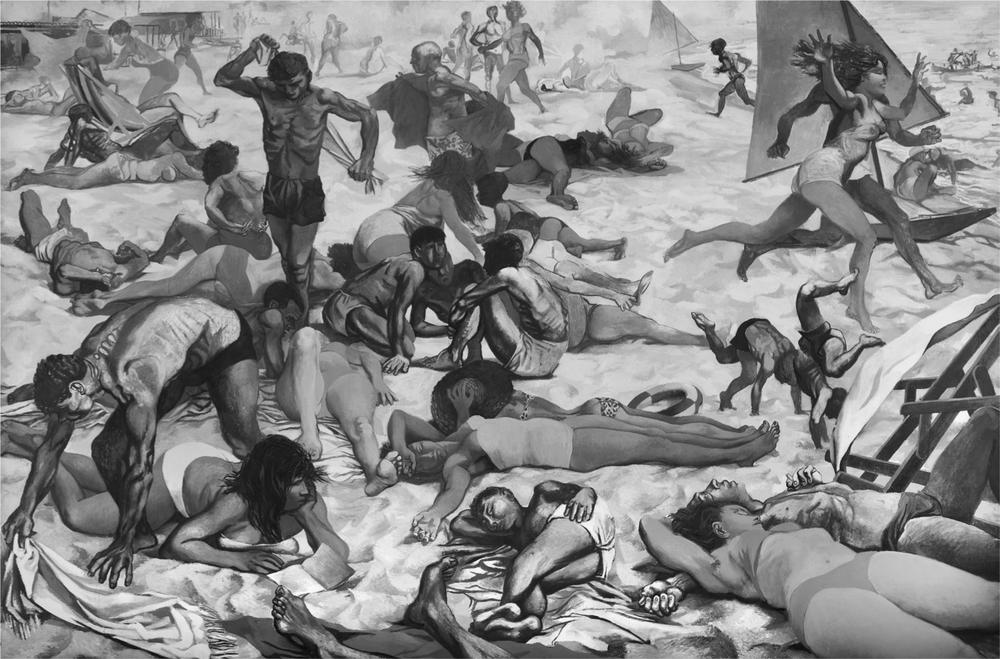

Guttuso’s more ambitious showings at the 1954 and 1956 Venice biennales were symptomatic of a shift away from the evidently political social realism of his work of the previous few years. These new works included a large-scale multi-figure representation of urban youth, Boogie-Woogie11 and one of ordinary people disporting themselves on a public beach, The Beach [2]. These two paintings could be seen as contrasting the alienated collectivities of modern urban mass entertainment with more free-and-easy forms of everyday sociality that were not subject in the same way to the forces of capitalist consumerism – with the beach scene possibly representing not just an actual reality, but something of a projected new proletarian society that would flourish under communism. The conception of The Beach, together with its broader political connotations, makes for an interesting comparison with the work of the American Philip Evergood, an artist very much of the left, who in the 1930s had been closely involved with Communist Party cultural initiatives, and who in the postwar period remained committed to figurative realism as the most effective basis on which to engage with the lived realities of the contemporary world.12

2 Renato Guttuso, The Beach, 1955–6, oil on canvas, 301 × 452 cm. Galleria Nazionale di Parma.

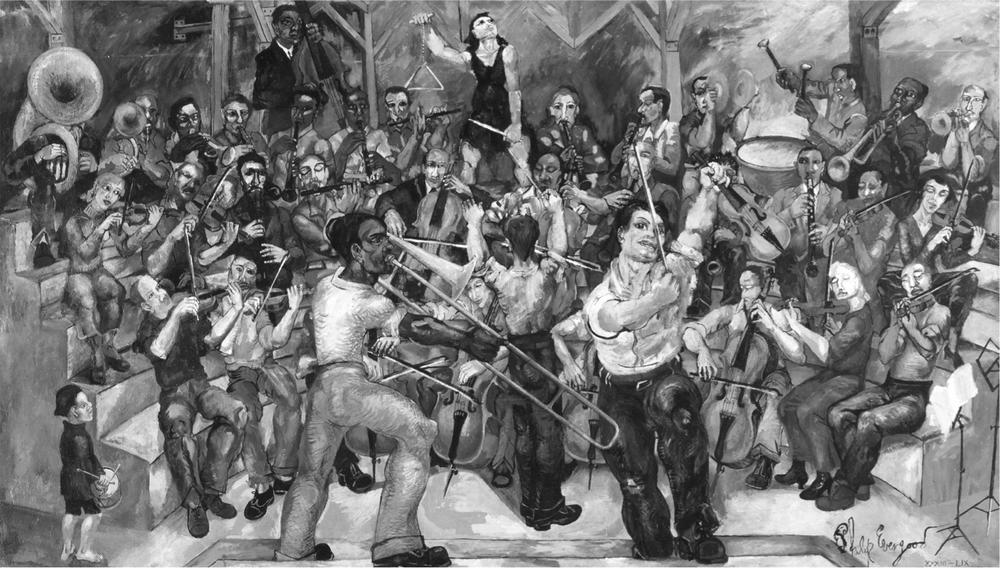

3 Philip Evergood, Music, 1933–59, oil on canvas, 170.2 × 303.5 cm. Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, Virginia.

Evergood’s mural-scale painting Music [3] – conceived in 1933 for the Pierre Degeyter Club in New York, a branch of the Workers Music League, and then somewhat reworked by him in the 1950s13 – is, if anything, a more evidently social-realist picturing of non-bourgeois sociality than Guttuso’s The Beach. It shows an energetic, non-hierarchical gathering of diverse types, come together to make music in a way that contrasts strikingly with the bourgeois formalities of a conventional orchestra performance. The two figures in the foreground are shown to be part of the group, the trombonist momentarily stepping forwards to make his solo contribution, and the fiddle player about to take up from the trombonist’s intervention, with neither singled out as lead figures any more than, for example, the equally vigorous lady in the centre background about to strike her triangle. This is an image both very real but also at some level utopian, more convincingly so because of its slightly ribald Hogarthian humour. The affinities suggested here between Guttuso and Evergood are not just retrospective projections. Evergood came to know Guttuso and admire his work when the latter had an exhibition at the ACA gallery in New York in 1963, and Guttuso took up an invitation from Evergood to write the introduction to the catalogue of Evergood’s show at Gallery 63 in Rome in 1963. Evergood responded enthusiastically to Guttuso’s essay, feeling it showed that they had a real ‘bond of understanding’ and thanking Guttuso for his appreciative insights into ‘what I have tried to say in the language of paint’.14

When Guttuso in 1949–50 emerged as a champion of realist painting with communist convictions, he did so from an immediate postwar context where a clear divide between a Marxist-inspired painterly realism and a more radical-seeming aformal abstraction was not yet firmly in place. He was associated with various anti-fascist artistic groupings that formed after the collapse of the fascist government, most notably the Fronte Nuovo, which included artists such as Vedova who later were to become leading practitioners of informel abstract painting. In 1948, Guttuso was signatory to a letter defending modern trends in contemporary art against an attack on these by Togliatti (writing under a pseudonym), who called for a socialist-realist aesthetic as the only viable form for a truly communist art and who denounced what he saw as the anarchy and the horrors, monstrosities and imbecilities of the work in the National Exhibition of Contemporary Art held in Bologna that year. Concurrently, however, a split had begun to open up between Guttuso and his realist associates in the Fronte Nuovo and the abstractionists, which led to Fronte Nuovo’s dissolution in 1950 when the two groups showed their work separately at the Venice Biennale. Guttuso’s emerging reputation as a champion of artistic realism at this point coincided with his developing closer relations with the leadership of the Italian Communist Party – he was made a member of its Central Committee in 1951.15 Still, he continued to argue as he had throughout the later 1940s for an artistic realism not bound by established convention, and distanced himself, not just from non-representational abstraction, but also from doctrinal socialist realism and traditional forms of naturalism.

An underlying commitment to a broadly realist approach to painting, and a scepticism about the more radically experimental postwar avant-gardism and the modernist ethos associated with it, combined with a certain openness and generosity, remained characteristic of Guttuso’s approach to the art of his time through much of his career. Such an outlook is consistent with the intellectual milieu in which he moved – among his close associates were figures such as Pier Paolo Pasolini, Alberto Moravia, Carlo Levi and Else Morante. When he reflected on the developments that had taken place in the Italian art world of the immediate postwar period, he took care to note the affinities between the practitioners of painterly realism and the more radical currents in early informel abstraction. Both, he felt, shared a compulsion to start afresh after the collapse of fascism, and both were dissatisfied with existing forms of modernist abstraction and Surrealist vanguardism.16

In his view, it was the group of so-called neo-realists who were the first to respond, before the practitioners of informel abstraction, to the imperative ‘to immerse themselves in the “world”’, an imperative he saw as reshaping postwar art and taking it beyond the formalistic orthodoxies of established modernism. This was, he explained, a moment of deep crisis when it became imperative for artists to ‘disavow their own gods, and have the courage [to take on] a new barbarism if they truly wanted to get at the roots of evil’ (namely the evil of both fascism and modern capitalism).17 While strongly critical of the self-referential, formalistic tendencies of later informel abstraction, and of its critical packaging as symptomatic of existentialist anxiety and pessimism, he saw the radical departure from the geometric norms of pre-war abstraction and the opening out to an expressionist disorder found in its earliest manifestations as driven by a revolutionary impulse broadly shared with the realists.18 Informel abstraction in his view had two currents, one characterized by an essentially conservative and anti-socialist rejection of politics, and one that in its striving for a qualitative transformation of painting’s expressive potential had its roots in revolutionary ideology. Among the Italian artists who espoused an aformal, radically non-figurative abstraction were those like Vedova who envisioned their art as enacting a passionate engagement with the conflicted and disturbing realities of the times.19

Guttuso saw Pollock as a very considerable painter, publishing an extended tribute to him in 1962 in which he argued that full appreciation of his work had properly to take on board its representational aspects and get away from a fetishizing of the purely abstract drip paintings of the years 1947–50 that dominated current critical presentations of the artist. His summing up of the contradictory tendencies in Pollock’s practice and of the conditions ‘of permanent catastrophe within which [this] artist of genius was formed’ is pretty astute. He saw Pollock as torn between a dramatic-epic ‘Mexican-Picassian’ symbolic impulse and a lyrical aspiration to naturalistic imagining, ‘a need for action and repose, intense collective life and solitude’, ‘a sense of the “modern” and need for the antique spectacle of “nature”’, with the former tendency taking on the character of ‘massacre’ and the latter that of ‘the American landscape’ – all played out in the context of the ‘turbulence and lacerations of contemporary society’.20 It bears mentioning here that Evergood, despite his polemic against the formalistic doctrines of pure abstraction that gained such ascendancy in the US, found it possible to say in a late interview that, while he had wanted to avoid the pitfalls of becoming either an ‘academician’ or a ‘Pollock-type painter’, he nevertheless also ‘wanted to be as free and daring as Pollock, or as disciplined as an Albert Ryder or a Giotto if I could’.21

Asger Jorn, who in Guttuso’s terms would have been a practitioner of informel abstraction,22 came to prominence in a postwar context in which he too saw himself as reacting against the formalistic orthodoxies of modernist geometric abstraction as well as the conservatism of academic naturalism. He believed that a truly radical, politically committed art, one that engaged in any compelling way with the realities of life in the modern world, could do so only by jettisoning traditional processes of pictorial depiction and representation and by working in the first instance with the physical immediacy of painting’s materiality. For him, it was not a matter of setting abstraction against figuration. He was, as he saw it, committed to the ‘value of pictorial figuration’, but one radically antithetical to naturalistic depiction.23 Like a number of his contemporaries, he wanted to hold onto an idea of realism, but not in its conventional sense. He saw the ‘materialist realism’24 that he championed as bringing to life a reality that was ‘in contradiction with existing reality’ and rather than merely depicting existing phenomena gave rise to its own powerfully striking and materially substantive pictorial figurations.25

What divided the politically engaged materialist realists and equally politically engaged artists experimenting with new forms of painterly abstraction, then, was not some formal dichotomy between figuration and abstraction. Ideologically, the difference between them had to do with different attitudes to avant-garde radicalism, with the informel abstractionists’ adherence to a systematic, avant-garde-like negation of inherited artistic forms separating them from the realists, even if both took the view that being a modern artist involved developing new ways of working. Politically speaking, a somewhat anarchistic Marxist radicalism was being pitted against a Marxism more in tune with that of the culturally liberal wing of the Communist Party. What mattered for both was the commitment brought to bear in the artist’s engagement with both reality and art. As Guttuso put it, the critical disputes over the priority of figurative and non-figurative tendencies in art represented ‘the degeneration to the lowest level of the fundamental debate between reality and alienation’. The real issue was not a greater or lesser degree of figuration, but the inherent quality of the drive motivating the artist, the direction in which it was going and its moral roots.26

At issue too was a fundamental divide over the artistic process that would enable a vital and compelling engagement with a larger reality to enter into the art work. For the figurative realists like Guttuso and Evergood, the basic model was a version of the one that had informed conceptions of realism and naturalism since the later nineteenth century. It runs roughly as follows. The artist’s lived sense of reality is registered in the artist’s mind as he/she apprehends and experiences something in the world, and this mental and psychic response is in turn directly transmitted into the work of art and re-embodied as physical phenomenon by way of the artist’s activity of depicting what he/she has sensed and felt. It is in this way that an artist’s human apprehension of something in the external world enters into the fabric of a painterly representation, bringing the representation alive in ways that a merely mechanical delineation of something observed would not.27

In the essay ‘Concrete communication and concrete images’ published in 1965, Guttuso explained his commitment to figurative realism and his relinquishing of non-figurative procedures as follows: ‘Art is above all a moral problem – I think that I gain certainty and doubt from the irrepressible presence of things – but a doubt and certainty that would make no sense, if it did not take account of “the World”. Therefore I consider figurative art not a convention but a necessity.’ For him, the artist’s active viewing and apprehension of things is registered ‘as an experience that is constantly being put to the test. In experiences, that fly by on our eyes, that in the end flow directly into our blood through our direct actions or the pages of newspapers’, and that in turn flow into a painting through the artist’s handling and shaping of the medium.28 In an essay on de Chirico published in 1970, he expanded on how the latter part of the process, particularly in so far as it engaged the viewer, played out: ‘To take account of the value of a painting with respect to its realism, this involves being led by the hand of the artist and forcefully apprehending the visible … this being led to see and penetrate things, to seize things, this is the philosophy of the painter.’29

A similar, if more down-to-earth view of painterly depiction as registering a directly felt engagement with things is to be found in statement published by Evergood in 1946:

What an artist puts into his work comes back to him. If he feels deeply about trees, he will observe them keenly and in his canvases they will stand firm, and sway, and shimmer, and grow old, and rot and die, and the young ones will sprout out of the ground again. He will make the trees live and others who have loved and observed trees will feel them live in his canvases…. He has experienced something important and he has made others conscious of how important his conviction is – even about trees.30

Interestingly, Evergood, like Guttuso, found he would often get the kind of stimulus needed to sustain his realist practice from magazine and newspaper illustrations, a point that suggests that certain aspects of the Pop New Realism of the later 1950s and early 1960s was closer to the figurative realism of the postwar period than it was to the more radical-seeming painting of the informel abstractionists and Abstract Expressionists. Both artists insisted on the importance of the humanist dimension to a figurative way of working with its registering of an artist’s directly felt engagement with people and things that distinguished it from non-objective abstraction. As Evergood put it in his characteristically crisp uncompromising way, in the dispute between radical abstractionist and realist tendencies, ‘the issue is no longer between representation and non-representation; it is between humanism and formalism’,31 with formalism here meaning abandonment of the representational and expressive potential of art.

For the figurative realism of artists such as Evergood and Guttuso, the materiality of what was being depicted mattered more than the materiality of the art work and of the painterly processes that went into its making. Still, they did see the latter as having a significant bearing on the capacity of a work to evoke in a compelling way the phenomena it was picturing, even if such concerns did not play a particularly central role in their declarations of artistic principle. For them, the materiality of things in general was important. Guttuso insisted that ‘man and thing are the sole theme that belong to a painter’ and that a painter, while having ideas, does not depict ideas only things: ‘only in the way and manner in which he paints can ideas emerge’.32 Both Guttuso and Evergood adhered to the view that painting did not just represent things but had to do with the nexus of things in the world at large. As Guttuso put it:

An apple, a bottle, a face, people at war or in peace, angels in heaven, ecstasies of saints, massacres, the damned in hell, crucifixions or concerts, newspapers, cinemas, museums, streets, landscapes, palaces and closed-up rooms, messed-up beds, discarded and dusty things, painting is the form of our coexistence in each of the elements or in all of them together.33

Evergood, in a statement published in the Daily Worker in 1942, similarly explained how his art was closely bound up with a conception of ‘life, people, buildings, objects, nature, as the complex product of interacting social and natural forces’.34

In the art of these modern realists, the materiality of the paint and drawing, while not foregrounded as the generative basis of their art as it is was by artists working in an informel, more radically abstract mode such as Jorn and Vedova, is still very much in evidence. Different elements and areas of the picture canvas are rendered with different kinds of painterly mark-making, and the materiality of the latter intrudes to the point of interrupting illusionistic transparency, in effect giving a material grittiness to what is being represented. In a work such as Guttuso’s The Beach [2], the bodies are rendered in quite different ways, some smooth and others hard and dry, and fashioned with a broken patchwork of painterly marks in varied colours (such distinctions mostly play out between the female and male figures, but not consistently so). Also striking is the way that Guttuso for the most part refused to give his canvases an overall lushly painterly feel, which would integrate the variegated depictive processes. A somewhat rebarbative materiality often makes itself felt, particularly in the intriguing works he produced in the late 1950s and earlier 1960s, many of them still lifes, where things tend to be resistant and untactile rather than sensuously textured, the arrangement of items awkwardly fractured, and the concatenations of forms messy rather than suggestively dense.35

A certain refusal of illusionistic or painterly richness, an at times uneasily dry or flat materiality, and an absence of sensuously saturated integration of the pictorial field are apparent in Evergood’s work too. He made the point that ‘the rawness of a violent piece of color against a dull, dead piece of color excites the eye very often much more than an all-over rainbow beauty quality.’ He also expressed an aversion to the refined sensuous touch and rich painterliness associated with good painting, stressing how he liked to put ‘things down flat’ in a no-nonsense way: ‘This is painting: it takes greater strength to do this than to brush and stroke, and when I find myself brushing and stroking I hate myself for it.’36 There may be more displays of brushwork in Guttuso, but a conventional sense of overall painterly richness is usually blocked by the presence of areas that are either slightly discordant or empty or casually messy and by the accented linearity and angularity of the black drawn marks.37 The refusal of a conventional aestheticizing of the paint and the depictive drawing is integral to the realist claims of such work.

For experimental materialists such as Jorn, conveying a sense of one’s immediate engagement with lived reality was realized by immersing oneself in the process of painting, in the give and take between the artist’s impulse and action and the material substance of the emerging painterly configurations. A consciously imposed depictive intent, compelling these configurations to conform to shapes remembered or observed, only interrupted the process and prevented the motifs being formed from taking on a life of their own.38 Even for artists who were committed to a figurative realism, this immersion in process would sometimes loom large in their understanding of how the art they were making would become resonant with their apprehension of and responses to the world in which they lived.39 Significantly, Evergood featured in the series of articles in ARTnews in the early 1950s on artists’ approaches to painting, among which is the famous description of Pollock’s drip process with photographs by Hans Namuth.40

The Materiality of the World and the Materiality of Art

For most abstractly inclined artists who had a radical political agenda, something rather different was at stake in their intensive involvement with the materiality of paint than a commitment to the internal parameters of art and the self-defining processes of making it. Such a high-formalist, Greenbergian mindset came to dominate only later on. Instead, what one finds in the comments made by critics and artists at the time are intriguing, often confused ruminations about how the material processes of fashioning a work had affinities not just with processes going on in the mind, but also with those taking place more broadly in the physical world. This was a materialist outlook that refused conventional categorical distinctions between mind and matter, between inner and outer worlds, between the materiality of painting and the materiality of the larger world of which it was part and which in some way it was evoking. As the painter Jean Dubuffet, an artist who was hardly on the left in politics, but who was a close friend and admirer of Jorn, put it: ‘The movements of the mind, if one undertakes to give them body by means of painting – have something in common – are close relatives perhaps – with physical concretions of all sorts.’41

Jorn’s reflections on aesthetics and on the broader material constitution of things offer particularly valuable insights into the outlook informing such a materialist conception of painting, partly because he was so actively involved with a number of radical artistic initiatives that took shape in postwar Europe, and partly too because of his political commitments that make him a radical vanguardist counterpart to the Italian communist Guttuso. He was an irrepressible activist, who brought to bear in his reflections on aesthetics a political perspective informed by, if also to some degree critically sceptical of, Marxist dialectical materialism.42 He was a founder member of the Situationist International, and a close friend of Guy Debord’s.43

Jorn’s painting is characterized by a free intermingling of often discordant agglomerations of stridently bright and also murkily coloured paint [4]. Like Dubuffet, he was committed to the view that the artist should be guided by an immersion in painterly process, and that the configuring of forms and motifs would be compelling only if pursued in the first instance without conscious representational intent,44 not because such a process made the resulting work expressive of the artist’s state of mind but because it was true to the underlying formation of things.45 The way Jorn’s reflections on aesthetics and the ‘natural order’ do away with categorical distinctions between human impulse and agency and the material environment of which they are part has certain affinities with currents of thinking in the materialist phenomenology of the period.46 His broader conceptualizing of materiality, however, has less to do with such philosophical trends than with recent scientific thinking about the nature of matter and underlying physical processes, and with Marxist, dialectical materialist theorizing of processes of social change and political revolution.

Jorn’s errant and intriguing meditations on the materialist basis of the aesthetic took shape in a book published in 1952, entitled Luck and Chance.47 Particularly striking is his characterization of the spontaneous, activating disruption he saw played out in aesthetic experience as a physical, material phenomenon like other natural processes. The aesthetic event’s breaking with a known, habitual and ongoing patterning of things, was as Jorn formulated it, ‘a self-contradictory capacity of matter’.48 Subjectivity, and hence too the subjective impulses which set in train an aesthetic phenomenon, were not to be thought of as immaterial or spiritual, as having to do with soul or mind existing independently of the material world. The subject, while ‘normally defined as the “conscious ego”, the observing, thinking feeling, active individual’, was in the final analysis ‘any exclusive or limited sphere of interest in matter, any system of action, any individuality … Every cell in the human body is an object and at the same time an area of interest, a subject or acting individual.’49 In other words, ‘we do not perceive the subject as “the conscious ego”, as is generally the case, but simply as a sphere of interest or a viewpoint in matter, and thus not as something outside this world but as something both of and in it’.50

Jorn’s conception of matter was shaped by recent scientific thinking in several ways. He was an avid reader of his fellow Dane Niels Bohr’s essays that were published in a book titled Atomic Theory and the Description of Nature.51 Most notably he picked up on quantum mechanical thinking about the behaviour of matter that challenged determinist Newtonian conceptions of causality – scientists were finding that particle behaviour at the atomic level was describable only in terms of statistical aggregates of events that on an individual basis occurred randomly and by way of discontinuous quantum leaps. He was also drawn to discussions deriving from Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle about how observation could not pin down atomic particle behaviour because the process of observation was itself a material event that disrupted what it was observing and was part of the phenomenon it was seeking to describe. This for Jorn offered an understanding of materiality in which the non-normative, disruptive aesthetic event could be seen as integral to the basic constitution of matter and changes taking place in the material world. For Jorn, because the ‘experimental evolution of the manifoldness of the universe and nature is of such a kind that we could well say that matter in all its regularity is an incurable gambler’, the aesthetic event, the sudden, unpredictable appearance of something unknown, was simply one of many accidental occurrences taking place in the physical world. Given that accident, ‘an event that occurs without demonstrable or calculable reason or purpose, or from causes that lie outside the immediately observed area and are not predetermined through insight or experience in those who experience it’, is so pervasive, ‘the function of chance is normal and ordinary’.52 Its deployment in art was certainly not to be seen as distinctive to art movements such as Dada or Surrealism.

4 Asger Jorn, Dead Drunk Danes, 1960, oil on canvas, 120 × 200.5 cm. Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebaek, Denmark.

In thinking of the real change that he saw being realized momentarily in a vital aesthetic phenomenon, in contrast to the more constant, relatively stable metamorphoses ordinarily taking place in the material world,53 Jorn was also taking into account post-Darwinian understandings of the unpredictable changes and mutations basic to processes of evolution. ‘Real evolution’, in his view, occurred by way of disharmonious breaks, eruptions of something unpredictable and unpredetermined.54 For him, then, the interplay between a relatively stable, ongoing constitution of things he identified with the ethical in the realm of culture, and the unpredictable, gratuitous eruption of excess he associated with the aesthetic, was ‘a natural phenomenon, the condition for all differentiation and elaboration of matter’.55

Jorn’s thinking of aesthetics in material terms clearly fed into his vanguardist conception of painting as a process that gave rise to something new, unintended and unpredictable that broke radically with accepted forms of picturing. It was also bound up with his anarcho-Marxist politics and his conviction that real social and political change could be realized only through a revolution that destroyed the existing system.56 The model he had in mind owes a lot to classical Marxist understandings of how a fundamental transformation of class relations could never be realized by way of incremental change but only through the violent revolutionary upheaval that occurred once an existing social order was no longer able to accommodate the new forces emerging within it and began to break down. At the same time, he took the basic form of this Marxist, sociopolitical model of historical process and radical change as operating more generally in the material world, whether inorganic, biological or human: ‘On the strength of its construction, every system, every sphere of interest, mental as well as physical, has an absolute limit of evolution, which it is unable under any circumstances to transgress in time or space except by dissolution in favour of the formation of a new and richer structure.’57

Jorn’s ontology posed two very basic problems for his radical libertarian political and artistic convictions, the implications of which are possibly played out more in his painting than in his writing. The aesthetic or revolutionary impulse to realize something radically new, on his understanding, was impelled by a subjective goal basic to all organisms’ strivings, consisting ‘of power, of expansion, of the most unlimited control of matter’.58 There was nothing, however, in the sudden eruptions of impulsive energy he associated with the aesthetic to guarantee that their effect would be an opening out to new liberating possibilities rather than a release of destructive force or a meaningless play of blind impulse. That was a risk that had to be taken – it was in the end, to quote the title of his book, a matter of ‘luck and chance’. In a painting such as Dead Drunk Danes [4], one is being presented, it seems, with a less-than-meaningful orgy of blind impulse – at least if one looks to the title, which refers to the Danish custom of taking a ferry to Sweden to get blind drunk on duty-free alcohol. The painting itself however is quite ambiguous; it seems not to form into the promise of a truly democratic interplay of impulse between freely acting agents any more than it necessarily conjures up a scenario of a blindly aimless alcohol riot – the visages that emerge from and engulf themselves in the paint work are monstrous but also intriguingl y vital.

The second basic problem posed by Jorn’s conceptions of materiality has to do with how, in material circumstances such as those of modern capitalism that were antithetical to and threatened by the realization of a revolutionary impulse that would bring about radical change, the aesthetic event could take shape as anything greater than a temporary ripple that ended up being little more than a hopeless play of wishful thinking. Jorn in effect posed the problem while leaving its implications dangling in one of his more telling characterizations of what he saw as the underlying subjective impulses of the aesthetic:

the deeper ego-perspective [which] occurs in the individual as wishes, dream, fantasies or ideas, which are the gradual consciousness of one’s own unreleased possibilities. Tied to feelings of dread about the elements that could threaten and hinder their realization, these form images which are straightforwardly ascribable to our physique in the mental atmosphere of imaginings. These sheer illusions are certainly built up of matter from the actual experienced world, but in their structure have nothing to do with it, as they are fantasies and self-delusions.59

When the impulse remained at the level of wishful thinking, which in Jorn’s reckoning would have been the case for most art being made at the time, it was in danger of becoming a reified ideal appropriated by the world from which it sought liberation: ‘All ideal or subjective thought is wishful thinking, invoked by capabilities or inner and organic sensory influences. The latent unsatisfied wish becomes a fixed idea or an ideal.’60 Certainly as time went on, Jorn became increasingly pessimistic about the potential for art to activate revolutionary impulses that would bring about real change. This was particularly so after his separation from the Situationist International as it became apparent to him that the group was beginning to see art as a hindrance to revolutionary activism, and even more so when the outburst of political radicalism in the events of 1968, in which Jorn participated, was suppressed and had to go into retreat. He felt that the claims to be made for the liberatory potential of art, given the social and economic conditions operating against any immediate possibility of revolutionary change, were very precarious:

The artist can create true art only in the most intense opposition to this so-called ‘real’ life. But at the same time this unnatural but vital opposition makes his own art unnatural and his aim, the perfect masterpiece, unattainable; for the more he opposes society, the more he opposes himself, and if he denies society he denies himself, reality being the only foundation on which he can build anything at all.

But if ‘Defeat is assured in advance’, it is not a matter of giving up: ‘it is dependent on the intelligence and drive of the individual artist how far he will go’.61

There is a way in which his painting can be seen as resisting a recuperation of libertarian impulse as fixed ideal or marginal play, in that it is suggestive of a gratuitous, potentially destructive vitality and a dissolution of fixed bearings. Jorn took issue with the ex-fascist Hans Sedlmayr’s pessimistically conservative diagnosis of the negative effects on art of a loss of centre (Verlust der Mitte) in the modern world.62 In his painting of that name,63 though, the ludicrousness, the monstrosity of what emerges in such circumstances of a radical loss of centre seems more in evidence than any intimation of a creative development of human capacities. Among the more negative effects seems to be the production of truly aberrant apparitions such as Sedlmayr himself. If other paintings seem less violently conflicted [4], one hardly sees in them a celebration of the liberatory potential of art-making. They testify to an oddly compelling but also disturbing envisioning of things that could realistically be materialized in the late capitalist world Jorn inhabited. The projection of imaginative possibility seems to be producing disorientating monsters, with this imagined world inevitably being mired in the world as it is, rather as the looming images are materialized in a flux of resistant if somewhat malleable paint.64

5 Asger Jorn, Stalingrad, le non lieu ou le fou rire du courage, 1956, 1957–60, 1967, 1972, oil on canvas, 296 × 492 cm. Silkeborg Kunstmuseum, Denmark.

The general tenor of the later works to which Jorn gave politically or ideologically loaded titles would seem to be decidedly ironic about the generative possibilities that might emerge from the aesthetic gesturing of his painting. Ausverkauf einer Seele, ‘clearance sale for a soul’, presents a pretty bleak prospect at first sight, even if tempered by a certain humour.65 At the same time, the paint work, which really mattered for Jorn, while suggesting a chaos more of dissolution than of potentially regenerative energy, is strikingly alive and powerful. Not much promise, but not a closure on promise either, which would after all be at odds with Jorn’s irrepressibly activist outlook. This is to some extent true of his most ambitious history painting, on which he worked off and on between 1956 and his death in 1973: Stalingrad, le non lieu ou le fou rire du courage (the non place or the mad laughter of courage) [5]. This work was devised as an attempt to figure in paint the unprecedented destructive violence of the battle of Stalingrad and its status as a world-changing event marking the beginning of the defeat of Nazism, and what was after all a communist victory. At first sight, it seems as if the work is little more than a slightly impure abstract field of paint, in which the faint traces of motifs evoking figures and buildings are largely obliterated. But in this white field of snowlike paint there is something more than devastation. The whiteness has a curiously impure beauty, not quite alive but not quite inert either, while on closer inspection faintly configured beings emerge here and there, suggestive perhaps of the ‘mad laughter of courage’ evoked in Jorn’s title. Again, the effectiveness of the painting is inherent in its materiality, both as paint work and as evocation of the material residues of an undeniably epoch-making and unimaginably violent event.66

The difference from Guttuso’s large-scale realist political history paintings, or his and Evergood’s more ambitious social-realist renderings of everyday life, could, it might seem, hardly be more radical, but only if one takes a conventional formalistic view of the situation and discounts these artists’ larger political and culture investment in their practice. It would be easy to set the latter’s explicit figuring of the human in contrast to what seems to be the almost total obliteration of any distinction between the human and the inhuman in the painterly materiality of Jorn’s work. Taking Jorn’s oeuvre as whole, however, there is usually a figuring of some kind of human presence, often indistinguishable from the monstrous and the animal, in the visages that emerge from the turbulent paint. Such suggestion is largely obliterated, but not completely cancelled out in the painting Stalingrad. Where, for all the differences, an affinity may be found between the two very different realisms discussed in this article – in addition to a painter such as Jorn holding onto ideas of animate and at times human presence – this may be a shared understanding of a less than clear-cut boundary between consciously motivated action and the blind workings of inhuman forces and impulses. In so much as both politically engaged realisms were shaped by Marxist materialism, both envisioned conscious human agency as immersed in a nexus of forces, human and animal, social and environmental, that largely lay beyond the purview of individual human agency.

1 Andrew Hemingway, Artists on the Left: American Artists and the Communist Movement, 1926–1956 (Yale University Press: New Haven and London, 2002). Other recent publications that address the persistence of figurative realism in the postwar period include Brendan Prendeville, Realism in 20th Century Painting (Thames & Hudson: London and New York, 2000) and James Hyman, The Battle for Realism: Figurative Art in Britain during the Cold War 1945–1960 (Yale University Press: New Haven and London, 2001).

2 On Evergood, see Hemingway, Artists on the Left, op. cit., pp. 140–4, 227–33.

3 On the importance of realism as an imperative in the non-figurative, more abstract work of the postwar period, see Alex Potts, Experiments in Modern Realism: Worldmaking in Postwar European and American Art (Yale University Press: New Haven and London, 2013), pp. 24–153. See also the discussion there of Jorn, pp. 383–98.

4 Richard Wollheim, ‘Guttuso’, in Guttuso (McRoberts and Tunnard: London, 1960). The British critics drawn to Guttuso’s work came from a wide spectrum, ranging from the more formalist Douglas Cooper to the left champion of social realism, John Berger.

5 Renato Guttuso, Mestiere di Pittore: Scritti sull’ arte de la società (De Donato: Bari, 1972). A number of key essays are translated into German in Renato Guttuso: Gemälde und Zeichnungen (Museen der Stadt Köln: Cologne, 1977).

6 Lara Pucci, ‘“Terra Italia”: The Peasant Subject as Site of National and Socialist Identities in the Work of Renato Guttuso and Giuseppe De Santis’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, vol. 71 (2008), pp. 315–44.

7 The two paintings by Guttuso are Occupazione di terre in Sicilia, 1953, 200 × 278 cm. destroyed, and Portella della Ginestra, 105 × 200 cm, Private Collection; illustrated in Pucci, “Terra Italia”, op. cit., figs. 7 and 12.

8 Guttuso, La battaglia del ponte dell’ammiraglio, 1952, 500 × 300 cm, Uffizi; a second version dated 1955 is in the Galleria Comunale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea. The conventional dramatic rhetoric was not much liked by some of his closest admirers – John Berger, Catalogue of an Exhibition of the Recent Works of Renato Guttuso (Ernest Brown and Phillips: London, 1955).

9 Many of these paintings had topical political overtones, such as the very fine Calabrian Worker’s Sunday in Rome (Rocco with a gramophone) dating from 1960–1 in the Pushkin Museum in Moscow.

10 Guttuso, Giornale murale-Maggio ’68, 280 × 480 cm, Ludwig Forum, Aachen, and I funeral di Togliatti, 1972, 340 × 440 cm, Museo d’Arte Moderna di Bologna; illustrated in Renato Guttuso 1912–2012 (Skira: Geneva and Milan, 2012), pp. 75, 152–3.

11 Guttuso, Boogie-Woogie, 1953, 165 × 205 cm, Museo de Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto, illustrated in Renato Guttuso 1912–2012, op. cit., p. 74.

12 See note 2.

13 Kendall Taylor, Philip Evergood: Never Separate from the Heart (Associated University Presses: London and Toronto, 1987), p. 87. Though Evergood did not make any significant changes to the painting, he invested enough in his retouchings to redate it ‘LIII-LIX’.

14 Taylor, Evergood, op. cit., pp. 130–1. In 1963, Guttuso gave Evergood one of his drawings, which Evergood presented as a gift four years later to his friends Ann and Bill Feinberg (drawing sold at Swann Auction Galleries in 2002).

15 There is a very informative analysis of the trajectory of Guttuso’s artistic career in the entry by Raffaele De Grada on Guttuso in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, vol. 61 (2004); available online.

16 Guttuso, Mestiere, op. cit., pp. 111–2.

17 Ibid., p. 116, from an essay ‘Informale’ published in 1965.

18 Ibid., p. 103–5.

19 See the essays by Vedova ‘It’s not so easy to paint a nose’ (1948) and ‘Everything should be re-implicated (1954) in Emilio Vedova (Milan: Charta, 2006), pp. 126–7.

20 Guttuso, Mestiere, op. cit., pp. 239–40.

21 Taylor, Evergood, op. cit., p. 176.

22 There seems to be no record of contact between the two artists, which would have been unlikely given their very different political and artistic affiliations.

23 Asger Jorn, Pour La Forme (Editions Alilia: Paris, 2001), p. 11 (first published by the Internationale Situationniste in 1957); and Discours aux Pingouins et Autres Écrits (École Supérieure des Beaux-Arts: Paris, 2001), p. 72–3.

24 Jorn, Discours, op. cit., p. 98 (1949).

25 Ibid., pp. 46, 137.

26 Guttuso, Mestiere, op. cit., p. 238

27 This process is evoked very eloquently by Maurice Merleau-Ponty in Oeil et Esprit (Gallimard: Paris, 1964), pp. 86–7.

28 Renato Guttuso (1977), op. cit., pp. 30–1.

29 Ibid., p. 50.

30 Herman Baron, Philip Evergood (ACA Gallery: New York, 1946), p. 27. See also the statement quoted in Hemingway, Artists on the Left, op. cit., p. 228.

31 Baron, Evergood, op. cit. p. 16.

32 Renato Guttuso (1977), op. cit., pp. 43, 48.

33 Ibid., p. 27, first published in 1942.

34 Taylor, Evergood, op. cit., p. 176.

35 See, for example, Guttuso, Interno con Accessori di Studio (damigiana, cesto e sedia), 1960, oil and gouache on joined sheets of paper laid down on canvas, 156 × 205 cm, Private Collection.

36 Taylor, Evergood, op. cit., p. 179

37 See, for example, La Discussione, 1959–60, oil and collaged newspaper on canvas, 220 × 249 cm, Tate, London; image on museum website and in Guttuso 1912–2012, op. cit., pp. 138–9.

38 This was a widely shared view at the time – see Potts, Experiments, op. cit., pp. 70–2.

39 See, for example, the comments by the American figurative realist Ben Shahn about how the painter needs to establish ‘a complete rapport with his medium … paint has a power itself and in itself’. At the same time he was deeply critical of the formalist denial of depiction by artists ‘who only manipulate materials’. John D. Morse (ed.), Ben Shahn (Praeger: New York and Washington, 1972), pp. 85, 83.

40 Fairfield Porter, ‘Evergood Paints a Picture’, Art News, vol. 50 (January 1952), pp. 30–3, 55–6.

41 Peter Selz (ed.), The Work of Jean Dubuffet (Museum of Modern Art: New York, 1962), p. 72; see also Potts, Experiments, op. cit., pp. 138–45.

42 He offered an extended critique of mainstream Marxist understandings of value in the book Value and Economy published in 1963; translated by Peter Shields in Asger Jorn, The Natural Order and Other Texts (Ashgate: Aldershot and Burlington, 2002).

43 On Jorn and Situationist International, see Karen Kurczynski, ‘Expression as Vandalism: Asger Jorn’s “Modifications”’, Res, vol. 53/54 (Spring/Autumn 2008), pp. 293–313; and ‘Asger Jorn and the Avant-Garde: From Helhesten to the Situationist International’, Rutgers Art Review, vol. 21 (2005), pp. 57–76.

44 Jorn, Discours, op. cit., pp. 143, 145 (1953).

45 Jorn, Forme, op. cit., p. 135.

46 The phenomenology of Merleau-Ponty is a good case in point, though the measured temper of his writing could hardly be more different from Jorn’s. For a somewhat different take on Jorn’s blurring of distinctions between human subjectivity and the non-human material world see Hal Foster, ‘Creaturely Cobra’, October, no. 141 (Summer 2012), pp. 5–12.

47 It was reissued with some additions in 1963; the later edition is translated in Jorn, The Natural Order, pp. 231–355.

48 Ibid., p. 256.

49 Ibid., pp. 243–5.

50 Ibid., p. 281.

51 Niels Bohr, Atomic Theory and the Description of Nature (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1934); first published in Danish in 1929.

52 Jorn, Natural Order, op. cit., p. 267

53 Jorn held to a decidedly non-static view of the basic nature of matter, ibid., pp. 271, 320.

54 Ibid., p. 278; this he likened to the splitting which occurs when a new organism comes into being (p. 284).

55 Ibid., p. 278.

56 Ibid., p. 331.

57 Ibid., p. 321.

58 Ibid., p. 322; see also his comment about how such impulses were at root ‘an aggression or conquest, a reaching out beyond the static ego’, ibid., p. 263.

59 Ibid., p. 301

60 Ibid., p. 301

61 Erik Steffensen, Asger Jorn: Animator of Painting (Edition Blondal: Hellerup), 1995, pp. 157–8, from an essay Jorn wrote in 1971.

62 He argued to the contrary that ‘modern man can from now on retain his faculties, indeed even develop them in these conditions’, Jorn, Discours, op. cit., p. 310.

63 Jorn, Verlust der Mitte, 1958, oil on canvas, 146 × 114 cm, Stedelijk Museum voor Actuele Kunst, Ghent.

64 In a painting such as Jorn’s Letter to My Son (1956–7, oil on canvas, 130 × 195.5 cm, Tate, London; image on museum website), given its title, one might be prompted to see in it an array of vital, possibly reassuring, or comic apparitions of various kinds, at the same time that it is not impossible to see in some of them a certain monstrosity and potentially aggressive power. Perhaps they are no more reassuring than the figures in fairy tales, or the monsters and humanoid figures on early medieval churches that Jorn admired.

65 Jorn, Ausverkauf einer Seele, 1958–9, oil with sand on canvas, 200 × 250 cm, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; image on museum website.

66 On Jorn’s Stalingrad, see Karen Kurcunski, ‘No Man’s Land’, October, no. 141 (Summer 2012), pp. 23–52 and Potts, Experiments, op. cit., pp. 383–4.