‘There is dissimulation everywhere under a coercive regime.’ Charles Fourier

‘All oppression creates a state of war.’ Simone de Beauvoir1

Scattered throughout the first issue of the Situationist International’s (SI) journal Internationale situationniste (1958) is a seemingly random selection of six images of women, an ad-hoc mixture of bathing beauties smiling, beguiling, crouching, posing, playing in water and reclining on horseback [1–6]. With no obvious alterations and no explicit recodings via captions or speech bubbles, these images obey the principle of ‘minor détournements’ (détournements mineurs). A ‘minor’ détournement was defined by the SI as an appropriated element that had no importance in itself and so drew its altered meaning(s) from the new context or location in which it was placed.2 Typically this consisted of press clippings, a neutral phrase or a commonplace photograph. In this instance, everyday commercial images were shifted from their original home in women’s magazines or pornographic magazines and relocated in the SI’s revolutionary journal. But to what critical effect? There seems to be no clear relation between these images and the anonymous mixture of articles in which they appear, including the following: ‘Le Bruit et la fureur’ (Anon.); ‘La Lutte pour le controle des nouvelles techniques de conditionnement’ (Anon.); ‘Problèmes préliminaires à la construction d’une situation’ (Anon.); ‘Les Situationnistes et l’automation’ (Jorn); ‘Pas d’indulgences inutiles’ (Bernstein); ‘Action en Belgique contre l’assemblée des critiques d’art internationaux’ (Anon.).3

Undoubtedly, this process of determinate misplacement or disjunctive conjuncture worked to challenge the conventional meaning or role of these images. No longer circulating in their intended home, these bikini babes cease to serve as the props to the goods they were meant to sell, such as holidays in the sun, beachwear, leisure lifestyles, etc. The vacuousness of their posing is exaggerated by the absence of a suitable or expected context. Instead, they bump and grind against their new situation. Juxtaposing the material to absurd effect, the SI succeeds in exposing the gendered, consumerist fiction that conflates images of woman with desire and glamour, as seductive traits to be projected onto the goods they support and promote. The function of these images is rendered ridiculous by the commodity’s absence in their new context. Yet, at the same time, their ornamental and seductive allure is presupposed and to some extent maintained. Any jarring effect of their détourned misplacement relies on their perceived erotic and superficial appeal, which clashes against the intellectual critique offered in the texts that they supplement. The members of the SI are in danger of replaying a decidedly feminized version of what Wolfgang Haug defines as the ‘sexual semblance’ of ‘commodity aesthetics’.4 That is to say, they are reliant on using the sex appeal of these types of eye-candy as a lure, either to enliven the dull rhetoric of the texts or to capture the interest of a potential buyer flicking through the journal, tempting them into reading the group’s critique of the society of the spectacle. In such a case, a limited transformation has occurred at the level of the reader, since the images are no longer directed at a presupposed female audience – the anticipated consumers of women’s magazines from where these images were sourced. Indeed, the same-sex audience for these images complicates heterosexist readings of them. And it should be noted that the SI’s ideal reader was not male or of a fixed sex or gender. These examples of minor détournements set up an ambiguous and fraught oscillation: on the one hand, they replay the fetishized character of the commodity-image or spectacle; on the other, they transform its workings by relocating it to a new, out-of-place, avant-garde context that exposes the ludicrously reductive function and fiction of the sign-woman as the stand-in for sexual semblance as such.

1 From Internationale situationniste, no. 1 (June 1958), p. 5.

2 From Internationale situationniste, no. 1 (June 1958), p. 7.

This analysis works in so far as the images are treated somewhat generically, as incidences of refunctioned or détourned spectacles. A more substantive and complex reading of the same images emerges, however, if the particularity of their historical context is taken into account, such as the specific types of postwar ‘women’s’ magazines in which they appeared. In an interview with Michèle Bernstein in 1999, I asked why these bikini-babe images were selected. Significantly, she began her answer by admitting that she was responsible for putting images into the SI’s journal. Her reason for including images in general was prompted by Lewis Carroll, who apparently said, ‘what is the use of a story without pictures’. This allusion may appear to deflate their significance. But I think it suggests that a particular use was at stake in the détournement of images from the world of popular, commercial-press culture, especially when it is considered that they were directed at a particular class of female consumers who bought magazines such as Elle (founded in 1945) and Marie Claire (founded in 1937 and running until 1944, and revived in 1954), which Bernstein acknowledged were the sources for the images. By the late 1950s, both Elle and Marie Claire had undergone a profound shift in the ideal of femininity promoted in their pages. During the 1940s, the focus had been on the ‘femme au foyer’, whose duty it was to keep a good home even in times of adversity (there was still rationing at this time). Many articles concentrated on ideas of domestic efficiency and on women’s contribution to rebuilding the French economy by giving birth. Despite women’s role in the Resistance, which had helped to secure their right to vote in 1944, the postwar role expected of women was still limited to being a good mother and housekeeper.5 Interestingly, there were no advertisements in these magazines during the 1940s, so selling goods (which were scarce after the war) was not the priority. The first advertisement for a washing machine appeared in Elle in November 1949.6 But selling a particular feminine role model certainly was a priority.

By the late 1950s, however, advertising à l’Américain was in full swing, with both magazines displaying glossy images of modern ‘must have’ household machines and gadgets, even if they were well beyond the average worker’s budget. Promoted alongside such supposedly labour-saving devices was a new ideal of the ‘superwoman’, targeting and challenging its young female audience, typically teachers or secretaries, to live up to the changing roles of women in the labour markets of the late 1950s and early 1960s, when more than the reproduction of children was necessary to rebuild the French economy. Surveys carried out by these magazines revealed that for these new women a life at home was no longer sufficient or desired.7 Women’s increasing financial contribution to the home was also reflected in surveys that showed the changing attitudes and expectations of men, who reportedly considered intelligence and common sense at the top of the list of qualities of an ideal wife, with domestic skills dropping to the bottom.8 Women were of course still expected to do the ‘double shift’, however, earning a wage on top of cleaning, cooking and bringing up baby. In fact, magazines such as Elle were promoting a very limited emancipation for women via gadgets, running advertisements such as ‘Moulinex liberates women’. In the 1950s, women still had few legal rights over their bodies, parental home or bank accounts, and these were not instituted until the late 1960s. But during this time, the image of woman was in flux, with an older ideal waning and a newer one yet to be fully formed. For the young, upwardly mobile audience of Elle or Marie Claire the ‘femme au foyer’ may not have been for them, but the roles on offer were still experienced as artificial, be it worker, citizen, mother or a glamourous ‘do-it-all, have-it-all’ superwoman.

3 From Internationale situationniste, no. 1 (June 1958), p. 11.

The reality of everyday life for most women was more banal and tedious, and certainly at odds with the shiny ‘alien settings of chrome and Formica’ advertised in magazines and forming the ideal domestic settings of American movies that inundated France after the war.9 A census in 1946 revealed that 20 per cent of dwellings in Paris had no running water, 77 per cent had no bathroom and 54 per cent had no inside lavatory.10 Even those who managed to move out of the inner-city slums to the new low-rent ‘grands ensembles’ – the suburban housing projects located on the outskirts of Paris – could not afford luxury items such as fridges and washing machines. Indeed, a survey in 1956 showed that 60 per cent of housewives questioned wanted such labour-saving devices but none could afford the substantial initial outlay.11 This proves that the burgeoning consumer or affluent society was socially selective, forcing an economic division between the haves and the have-nots, as well as a gender division between working men who were expected to provide these goods and their non-working wives who wanted them.

4 From Internationale situationniste, no. 1 (June 1958), p. 26.

5 From Internationale situationniste, no. 1 (June 1958), p. 24.

For the SI, everyone – male or female – was subjected to the alienating conditions of the society of the spectacle. As they put it in 1953: ‘A mental disease has swept the planet: banalization. Everyone is hypnotized by production and conveniences – sewage system, elevator, bathroom, washing machine.’12 Yet, the effects of this banalization were not symmetrical or gender-neutral, but rather uneven and biased. As Kristin Ross aptly describes it: ‘Women undergo the everyday – its humiliations and tediums as well as its pleasures – more than men. The housewife, that newly renovated post-war creation, is mired in the quotidian; she cannot escape it.’13 In the 1950s, it was the category of ‘woman’ that the society of the spectacle subjected to the coercive and dissimulating drives of everyday life more heavily than any other, constantly projecting fantasy images of the proper way to look, act, cook, etc. Images of women became the central site for the alienating machinations of the spectacle.

So as representatives of the spectacle’s technique of everyday control and regimentation, the images of women in the SI’s journal are more illustrative of the content of the texts in which they appear than it first seems. For example, the article ‘The Situationists and Automation’ concerns the deadening effects of standardization on our desires that results in ‘a total degradation of human life or the possibility of continually discovering new desires’; it is accompanied by a stereotypical bathing beauty.14 ‘The Battle for the Control of New Techniques of Conditioning’ talks of a race between free artists and the police in experimenting with, and developing the use of, new techniques of conditioning, such as advertising; a battle, that is, to find a non-repressive use that contests the spectacle’s controlled policing. This text is accompanied by an image of a semi-naked woman ‘flashing’, which condenses the criminalized act of indecent exposure with the titillating allure of the striptease.

From Bernstein’s perspective, however, these ‘bikini babes’ had two specific meanings to be played with. First up, they were ‘charmant’ and ‘splendid demonstrations of the natural look’, in the sense that they no longer bore what she called ‘secondary sexual attractions’, such as make-up, high heels, lacquered hairdos, all attributes of high-maintenance screen idols like Betty Grable and Marilyn Monroe.15 Such a ‘natural look’ at that time symbolized liberation from an artificially contained and concealed body, exemplified by the heavily corseted ‘New Look’ created in 1947 by Christian Dior. This restrictive garment can be understood as part of France’s postwar ‘return to order’, when women who worked in the war were expected to free up their jobs for the returning soldiers and suture themselves back into the role of housewife or glamorous superwomen. There are, of course, problems with Bernstein’s definition of the natural look. It tends to reinforce a rather essentialist reading of these images, as signs of the category of ‘natural woman’, at home in her essential element of water or playing with animals. What is glossed over is the obvious fact that the bikini-clad body is not natural, but a historically (un)dressed body, disciplined by a particular regime of zoned eroticization. It may even be seen as representative of a certain ‘body fascism’ with regards to the proper or socially acceptable type of body, namely youthful and of a certain weight, permitted to be displayed in this garment and in magazines such as Elle. The bikini is a peep-show garment, structured to draw attention to the very parts it barely covers, fragmenting the female body into erotic zones. Its shocking and provocative appeal can be gleaned from the fact that it took its name from the US atomic-weapons testing in the Pacific Ocean near Bikini Atoll. In the wake of the devastation wrought by such bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, things considered intense or shocking were referred to as ‘atomic’, and seductive or provocative women were often referred to as ‘bombshells’. Therefore, it is perhaps not a surprise that when two Frenchmen independently designed skimpy alternatives to the one-piece swimsuit in the summer of 1946, both acquired nuclear nicknames. Jacques Heim created a tiny two-piece called the ‘atome’; Louis Reard introduced his design on 5 July, only four days after the United States had begun testing in the Bikini Atoll. In a bold marketing ploy, Reard named his creation ‘le bikini’, implying that it was as explosive an invention as the bomb. It is hard not to think that it was precisely the provocative frisson of these images that Bernstein (anonymously, on behalf of the SI) was importing into the SI’s texts.

6 From Internationale situationniste, no. 1 (June 1958), p. 30.

Bernstein’s second interest in using these images of bikini babes presents a very different model of the body at stake. This is what she called their ‘paraplegic’ aspect. Most of the women on display were, in a certain sense, deformed in some way, disabled through the cropping of limbs. Their legs, feet and arms were effectively amputated by the photographic frame. In psychoanalytical terms, rather than a narcissistic desire represented by a whole body image, here circulates a desire for a pre-symbolic, pre-Oedipal body, represented by these sadistic ‘part objects’, bodies that are fragmented or castrated at the level of the visible. As photographic images, they are guillotined by the shutter and cut up by the processes of framing and cropping.16 No photograph is ever whole. Its frame is porous to what is located outside of it, and its meanings are supplemented by interaction with what comes up against its borders: other images and texts from different spaces and times.

Such an unstable web of signification is inherent to the montage aesthetic of détournement itself. But what needs to be resisted is a tendency to claim a general or transhistorical reading of the SI’s détourned images. The SI did not endorse the technique of appropriation per se. They insisted that to critically reuse existing images required an understanding of the targeted audience and the dominant meanings or codes in order to recode them. The SI was emphatic in defining détournement as a targeted tactic, reliant on established meanings in order to see and comprehend their undoing. I would argue that it is in the gap opened up by the slippage of meaning between a given signified (code) and signifier (material support) – which takes place through the ruination of the contingent or arbitrary, yet historical, linkage between the two terms of the sign – that a transformation emerges. Yet, the risk of misrecognition haunts the replaying of given images. This can be seen in the SI’s risk of repeating, rather than undoing, the sexist codification of these pictures. In order to deconstruct this code and to reconstruct their subversive potential, it is necessary to locate the specific postwar context of these images, even if this is something that the SI themselves failed to do.

For example, what Bernstein forgot to mention was that one of these ‘amputees’, reclining on horseback, was a culturally significant icon from the 1950s, namely Brigitte Bardot [6]. But I think such naming is crucial when considering détournement as a targeted assault. It exposes how images have particular, material affects, such as contributing to forms of socialization and processes of identification and dis/mis-identifications. In the late 1950s, Bardot stood for a new ideal of ‘woman’. Claire Laubier remarks that for the younger cinema-going generation of the time, the 1956 release of Roger Vadim’s film Et Dieu créa la Femme (And God Created Woman), starring Bardot as the adolescent heroine Juliette, represented a transformed portrayal of femininity. Instead of romantic, vulnerable women who like to please men, such as Monroe, or the distant, unobtainable screen star, such as the icy princess Grace Kelly, here was a more ‘earthy’, ‘identifiable’ female character that defied received morality. In her bare feet and blue jeans, she represented a sexually emancipated ‘femme-enfant’, a ‘Lolita with attitude’, a sort of female James Dean, as was noted at the time.17 The latter comparison presents a somewhat ambiguous figure of a female, as a man in drag, conferring on Bardot a masculine aura of independence and rebelliousness, whose predatory sexual encounters were undertaken without guilt or remorse. One critic even remarked that from the back she looked like a man, a reference to her athletic and sinuous frame. Whatever the gender ambiguity (or perhaps because of it), she symbolized a more instinctive (hence still naturalistic) subject, for whom men became ‘l’homme object’ – a feminine reversal that mirrors the conventional masculine, heterosexist desire that subjugates and objectifies its others. Nevertheless, she was a sign of sexual liberation, a reversal of the sex roles figured in the image of female revolt. No longer passive, she was an autonomous agent pursing her own intense experiences. And unlike the equally aggressive and predatory cinematic figure of the femme fatale, she did not have to die for her indiscretions. Perhaps this sign of rebellion or of the return of the repressed explains why the SI appropriated the particular image of Bardot into their texts.

Of course, Bardot also represented a home-grown – that is, French – rebel with a cause. This nationalized heroine could be read as a critique of what the SI described as France’s postwar colonization by American culture. The Marshall Plan of 1948 did indeed set up an unequal trading, a sort of one-way street whereby all things American could flow in, but all things French stayed at home.18 This Americanization was also read in terms of a feminization or effeminization and emasculation of French culture. While such terms suggest a heterosexist orientation, they nevertheless expose consumer culture as feminized, grasping something of the dominant symbolic codings of advertising at that time in which the reified image of woman was predominant. It also recognizes a particular gendered process of deceit or disavowal, in which the image of woman veils or dissembles what all of us, men included, are subjected to within the alienating logic of the commodity-form.

7 From Internationale situationniste, no. 9 (August 1964), p. 21.

Abusif images

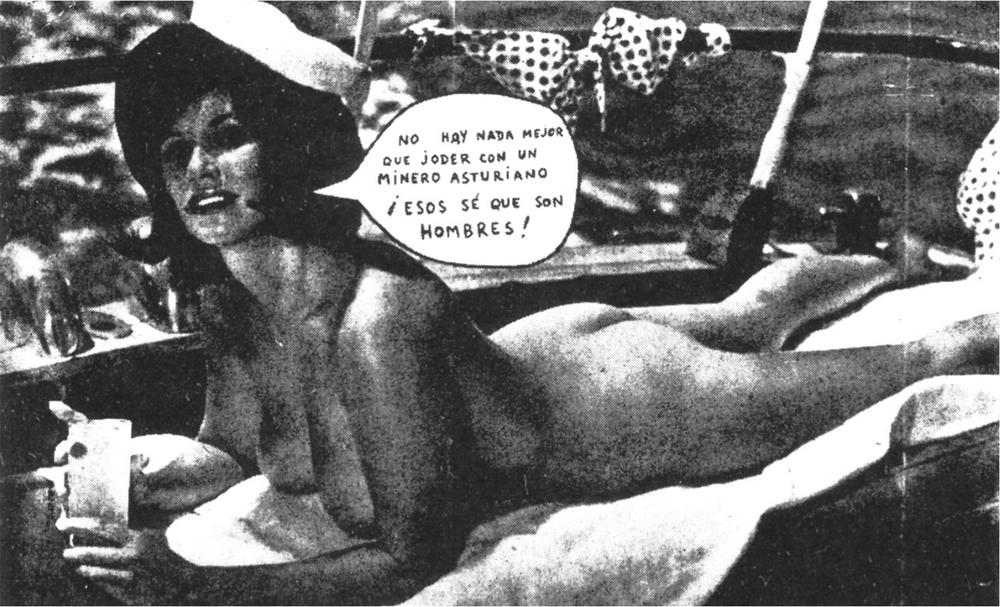

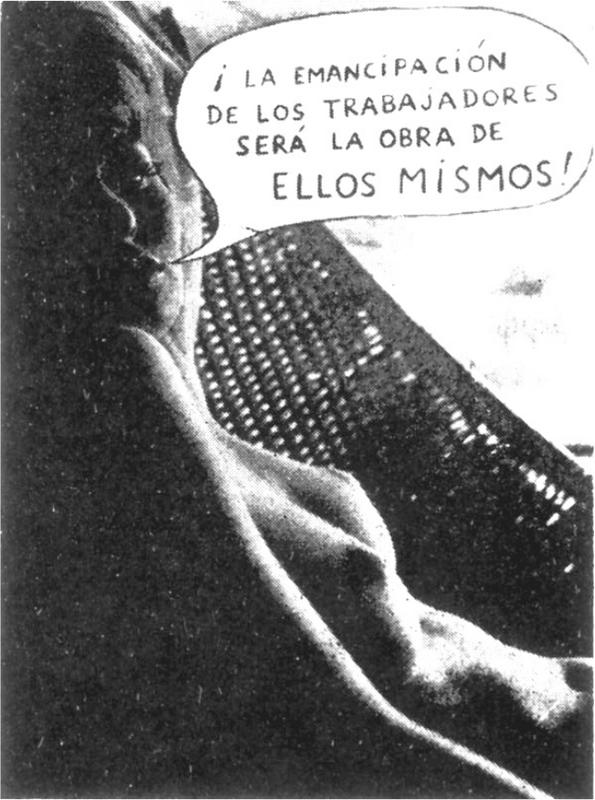

In issue 9 of Internationale situationniste (August 1964), three images of women appeared that may seem similar to the previous ones but present significant differences. They are different partly in so far as two of the images were sourced not from women’s magazines but from porn mags such as Playboy (first published in 1953), thereby presupposing an exclusively male audience. Also, unlike the bikini-babe images, all three can be considered as examples of ‘exorbitant’ or ‘excessive’ détournements (détournements abusifs). In contrast to a minor détournement, an exorbitant détournement was defined as the recontextualization of an intrinsically significant element, which derives a different scope from the new context, for example, a slogan by Saint-Just or a sequence from a Sergei Eisenstein film. This abusif form involves some alteration to the pillaged element, such as the addition of a speech-bubble or a new caption, as well as a new situation. Despite not being significant images by the likes of Eisenstein, these soft-porn images fit the abusif bill in being spatially relocated and significantly altered or damaged by the inclusion of an additional element. I will refer to them as ‘pop-porn’ images – my neologism to indicate the commercial massification of sexuality or pornography at stake within them.

8 From Internationale situationniste, no. 9 (August 1964), p. 36.

Let us consider the first [7]: naked on a boat, with a sailor hat at a jaunty angle, removed bikini strewn in the background, glass in hand, the girl’s bubbled utterance reads: ‘I know of nothing better than to sleep with an Asturien miner. They’re real men!’ And the second [8]: reclining in a hammock, glancing over her shoulder from her shadowy space, the girl bubbles the words, ‘The emancipation of the proletariat will be the work of the proletariat itself!’ These acts of excessive détournement are paradoxically both transformative and complicit in their effects. They are transforming in that the usually silent porn star of the magazine tableau not only looks directly at the viewer, but is also permitted to talk back. By breaking the auratic or distanced silence of her typically mute visual appeal, the images trouble the voyeuristic construction of most pornographic pictures. The private male gaze solicited by conventional porn mags is also abandoned by their new setting within the Internationale situationniste, which is (at least intended to be) public and ungendered. However, these images remain complicit with the sexual regime from which they are drawn in numerous ways. Consider what these women are permitted to voice and whose desire they speak of. In the first, the reduction of the woman’s desire to the task of pleasing and serving men reinscribes the fantasmatic presupposition of conventional heterosexist pornography. The desires ventriloquized here are, of course, those of the SI, and this act could be considered as a gesture of empowerment in that the empty image-spectacle is given a concrete, political consciousness. The reference to the Asturien miners was to a contemporary Spanish crisis, namely one of the longest-running miners’ strikes, virtually continuous since 1962. To speak openly in favour of it was to risk state censure and police arrest, hence any supportive images or literature, such as the SI’s, had to be smuggled into Spain clandestinely. This very censure is itself parodied by the use of a censored image.

A label was in fact given to porn images in the 1960s: ‘the sulphur of liberation’.19 This invokes a poisonous act of desublimation, in so far as pornography freed up sexual taboos in the form of exposed bodies, but only to convert them into sexualized commodities for the porn industry. This may be an example of what Marcuse termed ‘repressive desublimation’, whereby a loosening of social repressions served a process of redisciplining, in this case the control of the body for monetary purposes. Yet, disciplined or otherwise, these images were socially provocative, and it is perhaps this aspect that the SI intended to incorporate into their revolutionary texts. Despite the fact that even the détourned proletarianization of the second image does not necessarily challenge the conventional erotics deployed here, it is still the female body that acts as the ground for subversive or transgressive tactics. The sexual allure of the commodified female figure gets conflated with the sign for liberation as such. Sexual difference continues to drive the economy of the SI’s selected pop-porn images, in that the woman-as-sign or spectacle is the metonymic substitution of political revolution (the miners’ strike) for sexual revolution. The SI are decidedly of their time in this respect. But by presenting the sign-woman as an ideal figure for all rebels to identify with, in the sense of being privileged as the most appropriate visual form for the SI’s desire for revolution, an ambiguous process of cross-gendered projection is staged.

These pop-porn images also interact with the texts with which they are juxtaposed. The Asturien miner example is collaged among a medley of newspaper clippings sourced from French papers such as Le Monde and Paris-Presse, the British Observer and the Japanese Zenshin. What these clippings share is their insurgent content. References are made to various terrorist activities and armed insurrections carried out by students in Barcelona and Madrid. Support is given to various strikes, such as that of dockers in Denmark and sailors in Rio de Janeiro. Praise is given to the violent student protests against the presence of American Polaris submarines in Japan. All the events alluded to dated from 1963–4 and so are contemporaneous with the publication of the SI’s journal. The images of women are therefore moored against international acts of rebellion or terrorist insurgency against governments and the sociopolitical status quo. As with the ready-made texts, these ready-made, but altered, pop-porn images act as examples of what Greil Marcus describes as the SI’s practice of ‘intellectual terrorism’.20 This term refers to their détournement, theft and thus refusal of the intellectual property rights of published images. In this way, Marcus argues, the journal – itself copyright free – becomes a laboratory for experiments in ‘counter-language’ (and I would add ‘counter-spectacles’), whereby détournement becomes an act of ‘aesthetic occupation of enemy territory, a raid launched to seize the familiar and turn it into the other, a war waged on a field of action without boundaries and without rules’.21 This is an apt description of the anarchic tendency of détournement, or what Marcus defines as, ‘a politics of subversive quotation, of cutting the vocal cords of every empowered speaker’.22 In the case of the pop-porn images, I would argue it is also a case of metaphorically giving the disempowered a voice. As the Situationist Gil Wolman said of détournement: ‘Any sign – any street, advertisement, painting, text, any representation of a society’s idea of happiness – is susceptible to conversion into something else, even its opposite.’23 The outcomes of such reversals of perspective, however, depend on the contingency of the act of détournement, the concrete historical moment and context in which it is put into operation. When this situation changes, the reversal changes too or is even lost altogether.

In the case of the proletarianized porn star [8], she circulates amidst commentaries on the anarchist tendency of the SI group itself. The longest collaged snippet makes reference to a recent edition of the English magazine Tamesis (March 1964), which published an English translation (by David Arnott) of the SI’s text ‘All the King’s Men’, first published in issue 8 of Internationale situationniste (January 1963). The content of this text concerned the insubordination of words. Even if words are made to work on behalf of the dominant organization of life (the spectacle), they are not therefore completely automated: ‘Unfortunately for the theoreticians of information, words are not in themselves “informationist”; they embody forces that can upset the most careful calculation.’24 Therefore, the SI concluded that the so-called ‘newspeak’ of the spectacle (we can add here news images), its militarization of communication into information, was by no means inevitable. For the SI, this opened up the possibility for a new, immanently forged, anti-spectaclist poetry of life.

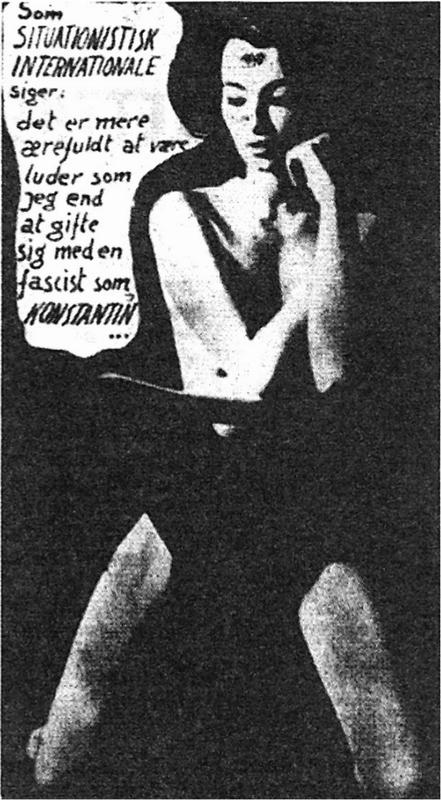

If these two pop-porn images were anonymously produced, the third and final one [9] was attributed to the Scandinavian Situationist J. V. Martin, who along with Bernstein, as well as Jan Strijbosch and Raoul Vaneigem, was an editor of this issue of the journal. The image, as with Bernstein’s Bardot, was appropriated from the popular commercial press. But unlike Bardot, this women has a speech bubble added, as well as an atypical, lengthy, explanatory, supporting caption that translates as follows:

Echoing the Spanish ‘comics’, which in a single blow received political censure as well as moral censure from priests, the SI distributed this photograph in Denmark on the occasion of the engagement of the daughter of the Danish, social-democratic king with the Greek sovereign, following polite protestations from the left. Christine Keeler, in the famous photo attributed to Tony Armstrong-Jones, here declares: ‘As the SI says, it is more honourable to be a prostitute like me than the wife of the fascist Constantin.’25

J. V. Martin produced a thousand copies of this image. The year before, Christine Keeler had become famous for having simultaneous sexual affairs with both a Soviet naval officer, Eugene Ivanov, and the British secretary of state for defence, John Profumo. Profumo lied about the affair and was later forced to resign. It was during this scandal that the celebrated photograph of Keeler naked, astride a copy of the Danish designer Arne Jacobsen’s ‘ant chair’, appeared. The image itself was apparently produced to promote a motion picture that was never realized. So Martin’s détournement of this image drew on its incendiary context.

9 From Internationale situationniste, no. 9 (August 1964), p. 37.

The other textual supports to this image include a quotation from Guy Atkins’ book Asger Jorn, published in 1964. It sets out the differences between Jorn’s involvement with the COBRA group and the SI. COBRA is described as a gregarious movement, with little discipline, which accounted for its purported growing out of control. The SI was, on the contrary, a closed and tight-knit group, less susceptible to breaks because of its disciplined and coherent character. Yet, the relation of text to image contradicts this premise by being far from coherent or disciplined in the outcome of its meaning. The SI’s practice turns on itself. It must be emphasized that its détournements could, in general, be subjected to retranslations and alternative slippages of meaning.

Situationist women

Susan Rubin Suleiman has written that, ‘[unlike the Surrealists,] the Situationists seem to have ignored women altogether, except perhaps as sex objects in the most banal sense’.26 This comment is, as I hope I have shown, characteristic of the neglected consideration of the SI by feminist readings. It reveals a certain reconstruction and acceptance of Surrealism by branches of a feminist, psychoanalytically informed cultural criticism, for which (typically) man-made images of women have been successfully mined for their sociopsychic revelations of masculinist fantasies of femininity. This derives, in part, from the image culture of the 1920s and 1930s, especially its comparatively closeted representations of sexuality, which enabled any exposure of the body (Surrealist or otherwise) to assume a scandalous or titillating allure. In contrast, the SI confronted the media culture of the late 1950s and 1960s, when images of sexuality are less coy, ‘letting it all hang out’. In this culture of openness, feminist-psychoanalytical readings derived from methods of desublimation are hard-pressed to deal with the blatant or conscious (not unconscious) exposure of desires and fantasies that are exploited to sell goods in the pages of magazines. I have argued that the SI’s appropriation of such conscious fantasies of femininity can also be critically mined to explain how and why such avowed (not disavowed) images, strategically expose the dissimulating or spectacliste character of the reigning image economy of the 1950s and 1960s, which obviously persists today in numerous ways.27 However, although I hope to have punctured the sense that the Situationists ‘ignored women altogether’, I concede that the situation of women in the SI is muted. But the question is how and why?

In important respects the reasons only confirm the suspicions of feminist commentators. In the first place there simply were not many women involved. Of the seventy members of the SI listed, only seven were women during the period 1957–67 (one of whom, Kata Lindell, subsequently became a man), and there were none between 1967 and the SI’s dissolution in 1972.28 And of these seven, only two can be described as active contributors in the sense of having a substantive role in producing and taking part in the construction of situations that utilized a variety of tactical formats including painting, sculptural tableaux, journal articles and books: Bernstein and Jacqueline De Jong.29 Such a small contingency of women seems to have encouraged a misrepresentation of the SI as a men’s club. But not only does this overshadow the fact that even this small contingency compares favourably with the female participants in other avant-garde artistic groups, it also downplays the contributions of Bernstein and De Jong.

Bernstein is perhaps not the best witness to her contributions to the SI, claiming that she ‘only took notes for the SI’. This may be recognized as a form of feminine self-effacement perhaps induced by male self-assertion. But it is mischievously modest. Before becoming editor of Internationale situationniste, Bernstein had been an active contributor to the Lettrist International group (a member from 1952 to its integration with the SI in 1957) and an editor, not just mimeographer/typist, of their freely distributed journal Potlatch.30 As a member of the SI from its inception, she not only took notes during their conferences but also contributed articles to their journal and was a member of its editorial team, along with five or six others (men), from 1963 to 1966.31 In the first issue of Internationale situationniste, Bernstein produced one of the more hard-core SI texts called ‘Pas d’indulgences inutiles’ (No useless leniency), which justified acts of absolute exclusion from the group so as to maintain its kernel of truth, intercut with a détourned image of a bikini babe – undoubtedly selected by Bernstein herself.32 Another important contribution was her article ‘Sunset Boulevard’, in praise of the cinematic technique of Alain Resnais’s Hiroshima, mon amour (1959) and against the new novel exemplified by the likes of Alain Robbe-Grillet and films such as The Last Year at Marienbad.33 Among Bernstein’s activities outside the SI, she wrote a ‘eulogy’ to Giuseppe Pinot-Gallizio’s model of ‘Industrial Painting’, in praise of its machinic, anti-authorial, collective, mass production.34 She also created anti-art works for the first and last so-called Situationist exhibition called ‘Destruktion Af RSG 6’. This consisted of a series of ‘Alternative Victories’; coincidentally an image and description of the latter was reproduced in issue 9 of Internationale situationniste, the same issue in which the bikini babes and pop-porn images appeared.35

As a former – or rather, dropped-out – Sorbonne student, Bernstein was considered one of the best writers in the group, and one of the few adept in English, which landed her the task of writing an article introducing the SI to the anglophone world for the Times Literary Supplement in 1964.36 She also wrote two novels, the first of which was called Tous les chevaux du roi (All the king’s men – a reference to Lewis Carroll again), published in 1960 by the prestigious house Buchet-Chastel. It depicted the everyday lives and loves of a young, modern couple called Genevieve and Gilles – versions of herself and her then husband Guy Debord (they were married from 1954 to 1971). There are psychogeographical wanderings through Paris; sexual intrigue as the two share a female lover called Carol; and in one scene where Gilles is asked what he is so busy with all the time, he replies ‘reification’. ‘It must be a lot of work’, his young lover says, ‘with lots of books and papers on a big table.’ ‘No’, replies Gilles, ‘mostly I just drift around.’37 This same dialogue would reappear as the speech-bubbles of two wandering cowboys on the cover of ‘The Return of the Durutti Column’, a tract distributed as a preamble to the ‘On the Poverty of Student Life’ pamphlet that appeared in 1966 during the student uprisings in Strasbourg. Bernstein’s second novel, La Nuit (The night), was also published by Buchet-Chastel in 1961. Here she retells the same story as in the first novel, but in the style of the ‘new novel’, replacing a linear narrative with a multiplicity of perspectives. As a consequence, the story appears in the form of a series of disconnected scenarios centred around night-time dérives about Paris. Both books’ themes of adultery and polymorphous sexuality mirrored the sexual ambiguity of Bernstein herself: ‘I don’t know if I was bisexual then, even though I looked like a boy and was thought to be a dyke. Later I became more one way.’38 The SI invented the term ‘marsupial’ to describe such a sexually ambiguous woman or androgynous ‘anti-woman’.39 This freedom of sexuality within the group contradicts the heterosexual perspective typically attributed to its détourned images of women.

Bernstein contributed to the SI in crucial indirect ways too. For example, it was through her contacts at Buchet-Chastel that Debord was able to publish The Society of the Spectacle. More importantly still, perhaps, her waged labour provided necessary funds both to live and to produce the glossy pages and shiny metallic covers of their journal, as well as backing other projects such as the short-lived attempt to open a bar called Le Methode, in homage to Descartes. She was the hidden motor running the SI, its economic secret. The various jobs she has been credited with include a race-track prognosticator, a horoscopist, a publisher’s assistant, a secretary at Éditions de Navarre, a journalist for the newspaper Libération and, surprisingly perhaps, a successful advertising director. With regards to the latter, Bernstein claimed, ‘To us, you understand, it was all spectacle; advertising was not worse than anything else. We took our money where we could find it.’40 It is worth mentioning that a year after she divorced Debord in 1971 – that is, also after she no longer provided money to him or the SI, or what was left of it by then – the group dissolved.

De Jong’s encounter with the SI was briefer; she was a member from the late 1950s to her expulsion in March 1962. She first became aware of the SI through an artist called Renee Nele (herself excluded from the SI in February 1962) and Nele’s contact with the German avant-garde group Gruppe Spur.41 When De Jong first met Jorn and Debord it was in Amsterdam while she was working at the Stedelijk Museum. The story goes that Jorn fell in love with her at first sight and it was through him that she joined the SI, allegedly to help organize revolutionary adventures in Amsterdam.42 With regards to the status of women in the group at that time, De Jong admits that there were always young girls hanging around Michèle and Guy, and that she was one of them. But, according to Bernstein, who was and remains a good friend of De Jong’s, her position, ‘as a very young, single-minded and unattached person was different’.43

One of De Jong’s first collaborations with the SI was what she describes as a ‘gesamt’ (that is, collaborative) work, produced during the fifth SI conference held in Gothenburg in 1961. It comprised a détourned painting with the heads of the contributors collaged onto the bodies of frolicking peasant-folk types: from left to right, the participants are named as, J. V. Martin, De Jong, Nash, Kunzelmann and Debord. De Jong in fact mentions an earlier collaboration when she visited Pinot-Gallizio’s experimental laboratory in Alba, Italy, in 1960. There she participated in the collective and anonymous production of rolls of Industrial Painting, examples of which had already been exhibited in Turin (1958) and Paris (1959). At the Gothenburg conference, De Jong proposed publishing an English-language journal to be called the Situationist Times. Ironically, it was produced only after her expulsion in 1962. This resulted from her solidarity with the Gruppe Spur, which was excluded in February 1962 on the pretext of its being too artistic. The expulsion took the form of a pamphlet published without commentary through the SI’s central committee and undersigned by Debord, Kotanyi, Vaneigem and Uwe Lausen, the latter a former member of the Gruppe Spur. Problems about the role of artists had already arisen at the conference, much to the displeasure of practising artists such as Heimrad Prem and Jorn’s brother, Jorgen Nash. But, for De Jong the 1962 pamphlet was more about petty jealousies and backstabbing.

While Nash and the other Spurists set up a Second Situationist International, a so-called ‘New Imaginist Bauhaus’ at Nash’s farm refuge, Drakabygett, in Sweden, De Jong finally got round to producing her journal, somewhat out of rage she admits. Through Jorn (who had resigned from the SI in April 1961), she managed to get Noel Arnaud to edit the first two issues. He was already an experienced editor of avant-garde journals such as La Révolution surréaliste.44 These first two editions were Rotaprint productions printed in East Holland on a rotary press and distributed in Paris. When De Jong better understood the process of journal production and distribution, she took over as the principal editor and publisher. Through the publisher P. V. Glob, another friend of Jorn’s, the Situationist Times expanded its distribution to other European countries until it got into financial trouble. After the sixth issue, the journal folded in 1967. Apparently, issue no. 7 was ready to go to press but there was no money to print it up; its theme was the ‘wheel’ – following earlier issues themed around ‘the ring’, ‘the spiral’ and ‘the labyrinth’. In stark contrast to Internationale situationniste, the Situationist Times was printed in bold colour and could be described as more artistic in that images and its visual appearance were a central aspect, and these outweighed more politically rigorous, theoretical texts.

On closer scrutiny, it is clear that both Bernstein and De Jong had considerable influence and effectiveness within the SI, despite the dominance of certain male members, notably Debord. And it is evident that their contributions were tied, if not literally married, to leading male lights. In an interview, De Jong endorsed a remark by Bernstein that, ‘I, myself and others were wives with an absolute uncritical solidarity towards Debord and obviously the SI in general’; De Jong went on to claim that it was because of this that ‘the expressions of the few women present left behind no traces’.45 These comments indicate the decisive ambiguity that pervades the situation of women in the group. In one sense, they may be read as a declaration of subordination, of both these individual women and women’s issues as a whole. In another, they declare a solidarity between women and men, between women and the SI, and between the SI and women. This solidarity should be subjected to scrutiny by feminist criticism, but such scrutiny should not blind itself to the political emancipation of women through revolutionary politics that are not dedicated to women exclusively. The fact is that, when faced with questions about the impoverished role of women in the SI, both Bernstein and De Jong appeal not to feminism but to a revolutionary identity that transcends sex, sexuality or gender. It is to these considerations of revolutionary identity and organization that the situation of women in the SI leads us.

The SI’s politics and mode of revolutionary organization was based on a critique of all forms of separation or division, such as that between workers and non-workers, young and old, blacks and whites, men and women. The danger of what the SI understood as separatist or micro-politics, such as anti-racism or anti-sexism, was its distraction from a critique of the totality of the spectacle. As the SI neatly put it, any singular or micro-revolt against the society of the spectacle ‘reassures the society because it supposedly remains partial, pigeonholed in the apartheid of “youth problems” (analogous to “women’s issues” or the “black question”) and is soon outgrown’.46 For the SI, only a total transformation of the socioeconomic conditions of spectacle – for example, its conversion into a form of non-authoritarian communism based on the model of workers’ councils – would or could bring about an end to a society based on alienated divisions. This is not say that the SI failed to recognize actually existing discrepancies between different social groups – see, for instance, their 1965 essay on the Los Angeles Watts riots, or their support of the battle for an independent Algeria, which includes a critique of the lack of freedom for women in this context.47

The broader question for the SI was how to eradicate such prejudicial marginalizations and hierarchical exploitations. The answer was always at the level of totality, of a total war on the spectacle, typically expressed in terms of a class war between those in control, the so-called directors of the spectacle, and those who were dominated by it, the so-called executants. Or to use the SI’s exact terminology, borrowed from Debord’s contact with Cornelius Castoriadis’s analysis in the group Socialisme ou Barbarie, a class war between ‘order-givers’ and ‘order-takers’. These terms entailed an expansion of the Marxian definition of the proletarian class in that the order-takers now included not only the workers, but also their managers and various technocrats – that is, those who did not own the factories – those out of work, or who refused to work, thieves and vagabonds, abject figures dismissed by Marx as the ‘lumpen’.

Just as the SI had a diverse yet particular range of cultural avant-gardist precursors – Dada, Constructivism, Surrealism, COBRA, Lettrism – so too they had specific political influences, from anarchism to non-authoritarian socialism, or what Richard Gombin calls the ‘radical tradition’ comprised of a non-aligned, non-Party-based leftism.48 The principal model of revolutionary organization appropriated by the SI was that of workers’ councils: but not before subjecting it to a sustained critique that exposed its historical failures. In other words, the SI’s support of this model was contingent upon an updated appraisal of its continuing use-value within the present moment. In two key texts from 1969, ‘Preliminaries on the Councils and Councilist Organization’ (Riesel) and ‘Notice to the Civilized Concerning Generalized Self-Management’ (Vaneigem), criticisms were laid out concerning ‘councilist ideology’, especially the tendency of ‘separation’ that had plagued existent councilist movements.49 Not only did many workers’ councils maintain a division of labour, but in practice (if not in theory) there was often a separation between the elected spokesperson and those doing the electing – this despite their avowed principles of direct democracy, under which the status of elected representatives is revocable at any moment. It was found, in fact, that those elected often operated independently of its constitutive body of voters, and not always on their behalf or for their benefit. For Riesel, such disjunctions can be surmounted only by ‘making the local general assemblies of all the proletarians in revolution the council itself, from which any delegation must derive its power at every moment’.50

On the plus side, however, council communism and workers’ councils (in a form based on the SI’s appropriation of the ideas of Anton Pannekoek) were founded on the principle of individual autonomy, in the guise of a self-creating species-being, without the need of an ‘other’ stepping in to represent oneself, with the attendant risk of reducing the difference of individual singularity to the class of the same: of some ‘other’ representative becoming one’s substitute. This explains the SI’s disdain of Leninism and Stalinism, where the head or leader ruled over the body of a subjugated proletariat – that is, the order-givers ruled its order-takers, forming a dictatorship of and not by the proletariat. In theory, the idea of leadership and disciples was anathema to the SI even if such an organizational ideal was not apparent in its practice of constant exclusions and realignments of their associative body/group.51 Nevertheless, autonomy and equality were the minimum requirements for the group’s model of revolutionary agency as indicated in the text ‘The Class Struggle in Algeria’: ‘Radical self-management, the only kind that can endure and conquer, refuses hierarchy within or outside itself; it also rejects in practice any hierarchical separation of women (an oppressive separation openly accepted by Proudhon’s theory as well as by the backward reality of Islamic Algeria).’52

It was this focus on creative autonomy, or what De Jong describes as their ‘elixir of creativity’, that drew her into the SI’s orbit. And it was/is this potential of the SI – its stress on transforming given situations oneself (with the help of like-minded others), without relying on the Party, unions, organizers or any other representative stand-ins – that also attracted later admirers such as anarchist-leaning Carol Ehrlich in her 1977 article ‘Women and the Spectacle’ (Spectacular Times, no. 7). As she wrote: ‘We must smash all forms of domination…. We have to see through the spectacle … but that work must be without leaders as we know them, and without delegating any control over what we do and what we want to build.’ When it comes to actions, she continues, ‘concede nothing to them, or to anyone else…. We make history or it makes us.’53 No doubt the SI would have fully endorsed such a Marxian commitment to self-making history. The obvious difference here, of course, is that Ehrlich gives a specifically gendered twist to women’s oppression by that ‘tormentor called culture’, with the spectacle operating as the root cause of a dominant and dominating patriarchal society. The SI never made such a clear-cut gender divide, since for its members all order-takers are exploited by the alienating conditions of spectacle whatever their age, sex or race.

Nevertheless, the SI was not afraid to champion the influence of specifically female role models. For example, they openly praised and cited Rosa Luxemburg; they rallied behind the actions of the infamous ‘pétroleuses’ of the Paris Commune; and they enthusiastically acknowledged the significance of women’s active participation in the Parisian ‘Events’ of May 1968, of which the SI wrote: ‘The extensive participation of women in all aspects of the struggle was an unmistakable sign of its revolutionary depth.’54 Also, with regards to May 1968, the SI, in its own book about the events, singled out and paid tribute to a female protestor who died fighting at the barricades.55 Such open support for the work and acts of women by no means signals a ‘feminist’ agenda. Indeed, it is safe to say that the SI members were not feminists. But I contend that this fact should be understood in a similar sense to Simone de Beauvoir’s contemporaneous assertion that she, too, was ‘not a feminist’.

Such an anti-feminist, or more accurately ‘anti-feminine’ stance, emerged in response to what de Beauvoir conceived of as the decidedly bourgeois and reformist outlook of many so-called ‘women’s groups’ existing at that time. As Claire Duchen explains in her book Women’s Rights and Women’s Lives in France 1944–1968, during this period the word ‘feminist’ was rejected by many women’s groups as evoking a pre-war, specifically pre-suffrage moment, before, that is, the securing of the right for women to vote, finally realized in 1945.56 The word feminist was considered the opposite of ‘feminine’, it conjured up an aggressive woman trying to be like a man. Most organizations, according to Duchen, preferred the label ‘féminin’, such as the Mouvement Démocratique Féminin (a non-communist, leftist women’s political club). Other groups such as the Union Féminine Civique et Sociale (a Catholic, conservative women’s organization) and the Union des Femmes Françaises (a communist-dominated women’s organization) also rejected the term feminist as old fashioned, out of step with new law reforms and legal rights for women (beyond suffrage) beginning to emerge at that time. Though, as Duchen notes, the actual changes in the situation of women at that time were very limited, with no real advances. Real changes in the Civil Code that would finally give women some rights over her home, bank accounts, family and own body – in the form of access to contraception – would not be implemented until the late 1960s and early 1970s. Instead, the common focus of many of these mainly bourgeois women’s groups was on limited legal reforms, usually for the benefit of a very selective and specialized female contingency.57

The beginnings of a broader challenge to patriarchy had in fact appeared in 1949, with the publication of de Beauvoir’s book The Second Sex. It immediately proved to be a bestseller. Its critical reception was, however, very mixed and predominantly negative. For example, Marie Claire was anxious that such a libertarian woman as de Beauvoir, whose desire for freedom rendered her ‘not real a woman’, should be allowed to teach children.58 The communist journal Les Jeunes Femmes was more positive about the breadth of issues covered, if still a little wary.59 The range and ambition of The Second Sex were hard to digest. It was not concerned with trying to achieve limited legal reforms for particular classes of women, but placed all women at the centre of a broader sociopolitical analysis, in particular challenging the social restrictions to women’s full autonomy. Unfortunately, the publication of The Second Sex was somewhat untimely. The breadth of its critique of the political situation of women was not fully appreciated or even recognized at its time. Yet, it would become an important source and literary tool for women’s emancipation post-1968, which involved attacks on the totality of ‘women’s situation’, including the ways in which the very idea of what it means to be a woman was socially contrived and mediated.

This attack aimed at the ‘total situation’ resonates with a Situationist position. As de Beauvoir wrote, ‘all oppression creates a war’, but the means to extricate oneself from this situation was not as her then partner Jean-Paul Sartre had imagined it. For Sartre, freedom lay in the possibility of transcending or escaping the given situation, and for him there was always the possibility of asserting one’s freedom. But, as de Beauvoir acknowledged, in light of her own experiences, in some situations the ideal of ‘freedom of choice’ for all was not always permissible, or possible, or else rendered free choice a delusion. Her example was that women (or rather the category ‘woman’) were trapped in their situation like rats, because they were not assigned any autonomy (or the faculty of reason) in the then current societal structure. To overcome such coerced limitations to their total situation, women had to abolish the social consequences and determinations assigned to sexual difference. For de Beauvoir, as for the later Situationists, freedom did not involve merely overcoming the ‘givenness’ or ‘facticity’ of a situation – this, in some sense, would be to accept a historical (and thus changeable) condition as if it were permanently fixed. Instead, freedom would emerge only through the radical negation and transformation of the concept of the already ‘given’ situation as such. It is the very coordinates of what is accepted as the given situation that needs to be revolutionized; at stake was the creative construction of a totally new situation and, ideally, new form of free, autonomous agency. As de Beauvoir writes at the end of the section ‘Women’s Situation and Character’, women must ‘reject the limitations of their situation and seek to open the road of the future. Resignedness is only abdication and flight, there is no other way out for women than to work for her liberation.’60 And if the members of the SI would not agree with limiting such a liberation to women only – since it opposed their more inclusive model of a new proletariat, the so-called order-takers – they would surely have concurred with de Beauvoir’s insistence that to succeed ‘this liberation must be collective’.61

By way of a brief conclusion, it could be argued that the SI, despite its opposition to single-issue politics, risked operating at a limited, micro-level by attacking the realm of cultural images. It needs to be remembered, however, that for the members of the group the spectacle, in the guise of capital become image, was a global phenomenon. Nothing remained outside its colonizing ways, just as nothing escaped the logic of the commodity-form. And if their critique of the spectacle at the level of images is in danger of reproducing women-as-spectacle, this is not so much a result of their being anti-feminist but rather as a consequence of the spectacle’s feminization of useful appearance, of a gendered asymmetry in capitalist uses of ‘sexual semblance’ to sell commodities. Spectacle commodity aesthetics uses women as the privileged sign of desire, or rather commodity aesthetics in the late 1950s and early 1960s was hegemonically coded as feminine. It was precisely the counterfeit character of such ‘sexist’ representations that the SI’s methods of détournement set out to perturb. Here, habituated responses, or what seems natural, were denaturalized, via a sort of Brechtian process of estrangement, which jolts and decouples commonplace encounters with certain types of images, such as the bikini babes and pop-porn. Through the SI’s processes of mimetic restaging and out-of-place resituating, a counter-hegemonic recoding is put into play. In 1957 the bikini babes were made homeless; disjointed and out of context, they questioned their role as superficial ornaments to the texts they supplemented. Such images were emptied out or revealed as empty signifiers, able to be filled-up with different connotations, thus succeeding in troubling the image of woman as ‘the’ sign of desire by making absurd their sexy veil or conceit. With the pop-porn images, the expected mute body of pornography is undone with their speech-bubble addresses to the viewer. This may be an act of ventriloquism on behalf of the SI, but by metaphorically speaking a political consciousness or an act of scandal-mongering, an unstable but generative space of engagement is opened up between the silent voyeur and the image that talks back.

At stake in the SI’s image war was a social or class war, and taking part was not, as I hope the above account of the role of Situationist women proves, limited to only the male contingent of the group. Their collective, egalitarian programme was to search out and invent a revolutionary inclusive, non-apartheid social situation, constructed by new types of radical agencies emerging from the prism of an altered or détourned spectacle. The task was not simply to cause the ruin of the spectacle at the level of images, which suggests an isolated project, but rather to see such détournements as part of an already global, decomposition of the spectacle evidenced, for the SI, by the battles in Cuba, Congo, Algiers and Saint Domingo. From a contemporary feminist perspective (as multiple as that can be), however, the group perhaps did not go far enough, by not taking into account how we are differently subjugated to, or terrorized by, the culture of the spectacle along the lines of race, sexuality or gender. We might all be saturated by the spectacle, but surely to different degrees of acceptance and resistance? In this light, it is fair to say that the members of the SI were a symptom of the situation and time that produced them, the late 1950s and early 1960s, when, as Bernstein said to me, it was not expected that a man could boil an egg.

Yet, as the SI diagnosed, even if you cannot step outside of the spectacle, you can refunction it from within, by speaking its language differently or by picturing a differenced world. Détournement was one strategy they used to defamiliarize and subvert the commonplace assumptions about the meanings and uses of certain images of women. It recodified the spectacle’s ready-made image banks, conferring on them what Valentin Voloshinov calls a different ‘accent’. In the case of the bikini babes and pop-porn images, the SI confronts the spectacle’s unseen and falsely naturalized sexism and so sets in motion a critique of commodity aesthetics that feminizes semblance itself. Its détournements expose this sexism as a particular, sociohistorical formation, not immutable or eternal, and therefore transformable. It does not resolve such gendered discriminations, but it does expose them to analysis. It questions the inevitable conquest of the social by its consumer images by revealing the work of dissemblance involved in those images’ production – namely, how the social relations that produced these images remain hidden. The spectacle tries to deny that its representations are the products of a particular (alienated) form of social labour determined by capitalist modes of production and consumption. To attack the spectacle is to attack capital – but who does this attacking? Who/what emerges from it? For the SI in the 1950s and 1960s, it was the task of anyone who felt alienated and wanted to change, or rather revolutionize, the total situation. Nevertheless, as a former Situationist claimed, what the SI lacked was a more nuanced model of the agents of revolution, and perhaps its ‘new revolutionary critique of the social’ would have benefited from ‘a sex revolutionary critique of culture’.62 A sense of differentiation, as being significant to the struggle against spectacular conditions, was acknowledged, somewhat belatedly, at the end of the SI’s life in 1972, when it declared that: ‘Everywhere the respect for alienation has been lost. Young people, workers, coloured people, homosexuals, women and children, take it into their heads to want everything that was forbidden them.’63 This is an untimely opening up of the new proletariat along a ‘differenced’ axis at the moment of the group’s own demise.

Too little and too late for some feminists perhaps, but in the cultural climate of the late 1950s and 1960s, the SI did deconstruct the sexing of commodity-images. Not, however, in the name of a pro-feminist agenda, but in the name of an autonomous, all-inclusive and hence unpredictable new proletariat; an emergent but not yet instituted figure constituted in part via new representational strategies such as the SI’s collective and anonymous détournements, intended to solicit and picture a different way to live within, but against, the machinations of the spectacle.

1 Both quotes from Simone de Beauvoir in The Second Sex, trans. H. M. Parshley (Picador: London, 1988), p. 627 and p. 726, respectively.

2 See Guy-Ernest Debord and Gil Wolman, ‘Mode d’emploi du détournement’, in the Belgian revolutionary surrealist journal Les Lèvres Nues, no. 8 (1956), p. 40. Here, they defined ‘minor détournements’(détournements mineurs) and ‘excessive or exorbitant détournements’ (détournements abusifs), and noted that any extended process of détournement would usually be composed of one or more sequences of exorbitant and minor types. This was a Lettrist text, but the basic principles of this method was continued by the SI, as evident in their essay ‘Le Détournement comme négation and comme prélude’ in Internationale situationniste, no. 3 (1959), pp. 10–11. See also the definition of this and other SI concepts in ‘Définitions’ in Internationale situationniste, no. 1 (1958), pp. 13–14. A later third model called ‘ultra-détournement’ was developed to describe actions of appropriation that took place in the street, such as reterritorializing public space with graffiti.

3 Articles in Internationale situationniste, no. 1 (1958), respective page numbers pp. 4–6; pp. 6–8; pp. 11–13; pp. 22–5; pp. 25–6; pp. 29–30.

4 See Wolfgang Fritz Haug, ‘Towards a Critique of Commodity Aesthetics’ and ‘The Ambiguity of Commodity Aesthetics as Exemplified in the use of Sexual Semblance’, in his Commodity Aesthetics: Ideology and Culture (International General: New York, 1987), pp. 103–20 and pp. 119–20, respectively.

5 The right to vote was secured in 1944, but not exercised until 29 April 1945. See Claire Duchen, Women’s Rights and Women’s Lives in France 1945–1968 (Routledge: London, 1994), p. 35. See also Claire Laubier (ed.), The Condition of Women in France 1945 to the Present: A Documentary Anthology (Routledge: London, 1990), esp. chapters 2 and 3.

6 Ibid., p. 2.

7 As one journalist put it, ‘they don’t want that life, restricted to domestic tasks; housework, housekeeping, children and nothing else’; see Duchen, Women’s Rights and Women’s Lives in France 1945–1968, op. cit., p. 92.

8 Ibid., p. 94.

9 Kristin Ross, ‘French Quotidian’, in Lynn Gumpert (ed.), The Art of the Everyday: The Quotidian in Postwar French Culture (New York University Press: New York, 1997), pp. 19–28 (p. 24).

10 Duchen, Women’s Rights and Women’s Lives in France 1945–1968, op. cit., p. 76.

11 Ibid., p. 75.

12 See ‘Formulary for a New Urbanism’ attributed to Ivan Chtcheglov published in Internationale situationniste, no. 1 (1958), pp. 15–20. Abridged version in Ken Knabb (ed. and trans.), Situationist International Anthology (Bureau of Public Secrets: Berkeley, 1995), pp. 1–4 (p. 2).

13 Ross, ‘French Quotidian’, op. cit., p. 24.

14 Knabb, Situationist International Anthology, op. cit., p. 47.

15 All quotes from my interview with Bernstein at her home in 1999.

16 See Frances Stracey, ‘Situationist Photo-Graffiti’, in David Cunningham, Andrew Fisher, Sas Mays (eds), Photography and Literature in the Twentieth Century (Cambridge Scholars Press: Cambridge, 2005), pp. 123–44.

17 For these different interpretations of Bardot, see Laubier, The Condition of Women in France 1945 to the Present, op. cit., pp. 34–41. The ‘Lolita with attitude’ reading was by Simone de Beauvoir.

18 On the biases of postwar US aid in Europe, see Brian Holmes, ‘Invisible States: Europe in the Age of Capital Failure’, in Simon Sheikh (ed.), Capital (It Fails Us Now) (B_Books: Berlin, 2006), pp. 29–57.

19 See Laurence Bestrand Dorléac, ‘The Art Scene in France, 1960–73’, in David Alan Mellor and Laurent Gervereau (eds.), The Sixties: Britain and France 1960–1973 – The Utopian Years (Philip Wilson: London, 1997), pp. 30–55 (p. 43).

20 Greil Marcus, Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the Twentieth Century (Picador: London, 1997), p. 178.

21 Ibid.

22 Ibid., pp. 178–9.

23 Quoted in ibid., p. 179.

24 Knabb, Situationist International Anthology, op. cit., p. 114.

25 Internationale situationniste, no. 9 (1964), p. 37.

26 Susan Rubin Suleiman, Subversive Intent: Gender, Politics and the Avant-Garde (Harvard University Press: Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1990), p. 214, n. 44.

27 Guy Debord uses the term ‘spectacliste’ in La Société du Spectacle (Gallimard: Paris, 1992), thesis 14, p. 21.

28 See The Incomplete Work of the Situationist International, trans. and ed. Christopher Gray (Free Fall Publications: London, 1974), pp. 162–3.

29 As De Jong clarified in an important interview in 1998, at the time of a revived Situationist exhibition, other than Bernstein and herself, ‘there were no other active women involved or rather who were members. Gretel Stadler and Kata Lindell (who later became a man) were present at Göteberg but no more than the women of … (no names given) … however without other activities than being listeners in the audience’. See Jacqueline De Jong interview with Dieter Schrage, published in the exhibition catalogue, Situationistische Internationale 1957–1972 (Musuem Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig: Vienna, 1988), p. 69 (my translation).

30 Berstein’s contributions to the Lettrist International include her participation in the first screening of Debord’s film Hurlements en faveur de Sade (1952), where she emitted a piercing scream and hurled bags of flour at the audience; she was an editor of Potlatch (1954–9), the title and concept of which, referring to forms of North American gift-exchanges, was also attributed to Bernstein; she published articles on the concept of the dérive, see her ‘Dérive au kilomètre’ in Potlatch, nos. 9–11 (1954), p. 64; also on the use of psychogeography, see ‘Le Square des missions étrangères’, Potlatch, no. 16 (1955); see also her important contribution to ‘Le project d’embellissement rationels de la ville de Paris’, Potlatch, no. 23 (1955).

31 She was an editor on issues 8 (1963), 9 (1964) and 10 (1966).

32 See Internationale situationniste, no. 1 (1958), pp. 25–6.

33 Internationale situationniste, no. 7 (1962), pp. 42–6.

34 See ‘Éloge de Pinot-Gallizio’, in Pinot-Gallizio (Bibliothèque d’Alexandrie: Paris, 1960), n.p. See also Frances Stracey, ‘Pinto-Gallizio’s Industrial Painting: Towards a Surplus of Life’, in Oxford Art Journal, vol. 28, no. 3 (2005), pp. 391–405, esp. p. 395.

35 Internationale situationniste, no. 9 (1964), pp. 43–4.

36 In Internationale situationniste, no. 10 (1966), p. 83.

37 For more on the background of these novels, see Andrew Hussey, The Game of War (Jonathan Cape: London, 2001), p. 183.

38 Ibid., p. 182. And in an interview with me in 1999, Bernstein made it clear that any sexuality was permissible among the SI; that they were young, carefree and experimental.

39 Ibid., p. 184.

40 Marcus, Lipstick Traces, op. cit., pp. 377–8.

41 It was at the third international conference of the SI in Munich, April 1959, that the Gruppe Spur registered its affiliation to the group. In their manifesto, the Gruppe Spur championed a new aesthetic against the ‘decomposed ideal beauty of the old world’ and against ‘the tired generation, the angry generation, everything is buried. Now it is the turn of the kitsch generation. WE DEMAND KITSCH, FILTH, ORIGINAL MUD, CHAOS. Art is the shitheap where kitsch is staking its claim.’ See Hussey, The Game of War, op. cit., p. 135. When De Jong met Prem, she was impressed by his charisma and energy, and as an experimental painter in her own right was drawn to Gruppe Spur’s radical, expressionist ideas since, as she stated in a 1998 interview ‘they appeared to be more attuned to my of thinking than the informelles or Mack, Piene, even more than the Zero-Gruppe’. From ‘Jacqueline De Jong: Eine Frau in Der Situationistischen Internationale’, an interview with Dieter Schrage in Situationistische Internationale 1957–1972, op. cit., pp. 68–71, (p. 68) (my translation).

42 On Jorn’s meeting with De Jong, see Hussey, The Game of War, op. cit., p. 149.

43 Schrage interview in Situationistische Internationale 1957–1972, op. cit., p. 69.

44 Ibid., p. 71.

45 Ibid., p. 69 (my translation).

46 From ‘On the Poverty of Student Life’ (1966), republished in Knabb, Situationist International Anthology, op. cit., pp. 319–37, (p. 326).

47 See ‘The Decline and the Fall of the Spectacle-Commodity Economy’, in ibid., pp. 153–60; and ‘The Class Struggle in Algeria’, in ibid., pp. 160–8.

48 Richard Gombin, The Radical Tradition: A Study in Modern Revolutionary Thought, trans. Rupert Swyer (Methuen & Co. Ltd: London, 1978). On ‘Socialisme ou Barbarie’, see Cornelius Castoriadis [Pierre Chaulieu], La Société bureaucratique (Union Générale d’Éditions: Paris, 1973). For Debord’s relation to ‘SouB’, see Shigenobu Gonzalvez, Guy Debord ou la beauté du négatif (Éditions Mille et une Nuits: Paris, 1988), pp. 31–6.

49 See ‘Preliminaries on the Councils and Councilist Organization’ (René Riesel) and ‘Notice to the Civilized Concerning Generalized Self-Management’ (Raoul Vaneigem), republished in Knabb, Situationist International Anthology, op. cit., pp. 270–82 and pp. 283–9, respectively. For example, Riesel castigates the one-sidedness of the practices of the KAPD (German Communist Workers Party) ‘who adopted councils as its program but by assigning itself[,] as its only essential tasks[,] propaganda and theoretical discussion – ‘the political education of the masses’ – it left the role of federating the revolutionary factory organization to the AAUD (General Workers’ Union of Germany)’, ibid., pp. 277–8.

50 Ibid., p. 271.

51 See the SI’s ‘manifeste’ (17 May 1960) in Internationale situationniste, no. 4 (1960), pp. 36–8.

52 ‘The Class Struggle in Algeria’ (1965), in Knabb, Situationist International Anthology, op. cit., pp. 160–8 (p. 167). In reference to Proudhon, it is worth noting that despite the SI’s links to certain anarchist tendencies, such as the Anarchist Federation, represented by Guy Bodson, and brief exchanges with the review Informations et correspondences ouvrières (formerly Informations liaisons ouvrières, born in 1958 from a scission with Socialisme ou Barbarie) and with L’Union des groupes anarchistes-communistes, the SI never joined another political group; although links with the group Libertaire de Ménilmontant in Paris did have some practical consequences when member Gérard Joannès produced a détourned comic illustration for a text by Vaneigem which appeared in Internationale situationniste, no. 11 (1967). See Gonzalvez, Guy Debord ou la beauté du négatif, op. cit., pp. 34–5. For illustration, see Internationale situationniste, no. 11 (1967), p. 35. In general, anarchism was too nihilistic for the SI, whose project was fundamentally reconstructive, namely to build on the ruins of the spectacle. And as to why the SI never joined another group, this can perhaps be deduced from their explicit desire to ‘perform revolutionary tasks’, rather than be a revolutionary organization per se. On the SI’s model of revolutionary organization in general, see Guy Debord and Gianfranco Sanguinetti, The Veritable Split in the International (Chronos Publications: London, 1972).

53 Carol Ehrlich, ‘Women and the Spectacle’, Spectacular Times, no. 7 (1977), p. 16.

54 See Anonymous, ‘The Beginning of an Era’, Internationale situationniste, no. 12 (1969) translated in Knabb, Situationist International Anthology, op. cit., pp. 225–6 (p. 226).

55 See Enragés et Situationnistes dans le Mouvement des Occupations (1968), republished in its original format (Gallimard: Paris, 1998).

56 Duchen, Women’s Rights and Women’s Lives in France 1945–1968, op. cit., p. 170.

57 For example, the Union Professionelle Féminine (Union of Professional Women) sought better working conditions for professional women only, as too the Association Françaises Diplômées des Universités (the Association of French Women University Graduates), which only represented female, graduate interests. See ibid., p. 167. Even umbrella groups for various socialist and communist parties sought rights for specific groups of working woman, seeking better pay conditions, but seemingly unconcerned with expanding such benefits and opportunities to ‘all’ women in general. This is even true of the likes of the broader sounding Le Conseil National des Femmes (National Women’s Council), which did indeed focus on equal rights for women, but only those who were married. Whether liberal, socialist or bourgeois, the majority of then existing women’s groups supported limited legal reforms, in local areas, rather than campaigning for a more universal improvement of the situation of women in total: that is, there was no united, mass women’s movement wanting to challenge the patriarchal state per se.

58 Ibid., p. 188.

59 Ibid., p. 176. On the mixed reception of The Second Sex, see also Laubier, The Condition of Women in France 1945 to the Present, op. cit., esp. chapter 2, ‘Le Déuxième Sexe’, pp. 17–27.

60 Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex, op. cit., p. 639.

61 Ibid.

62 See ‘The Revolution of Modern Art and the Modern Art of Revolution’ (1967), a pamphlet by the English section of the SI (T. J. Clark, Charles Radcliffe, Donald Nicholson-Smith), republished as The Boomerang series, no. 3 (Chronos Publications: London, 1994): ‘From now on the possibility of a new revolutionary critique of society depends on the possibility of a sex revolutionary critique of culture and vice versa’, p. 8.

63 The Veritable Split in the International (1972), op. cit., p. 19.