SCARS ON THE LANDSCAPE

DORIS SALCEDO BETWEEN TWO WORLDS

As they might do in any public square in a Western European city on a sunny day, people gather and casually stroll among the pigeons that flock around the Plaza de Bolivar, the central square of Colombia’s capital city, Bogotá. The imposing facade of the grandiose colonial buildings that flank the square adds to the monumentality and the tranquility of the place. One could easily mistake it, with its sun and strollers, for St Mark’s Square in Venice. But the Plaza de Bolivar is no European urban idyll. Pedestrian and public it may be, but the tranquility of the place is under constant surveillance and policed by an alarming number of soldiers menacingly armed with submachine guns. In keeping with the brutal history that afflicts the country, the square, the location of important government buildings such as the National Congress, has had its role to play in civic bloodshed.

The Palace of Justice on its northern side was witness, in 1985, to one of the most notorious confrontations between Colombia’s guerrillas and its government – a confrontation that resulted in many of the country’s judges, as well as a large number of fighters and civilians, being killed. Unlike the siege of the Opera House in Moscow in 2002 that received substantial worldwide coverage in the media, brutal events in a ‘Third World’ country such as Colombia have very little global news value. The Colombian artist Doris Salcedo has, over the last decades, been persistently attempting to keep alive in the public consciousness events such as these, events that the West would be happier to ignore, if not to forget. As an artist whose work since the 1990s is rarely exhibited in her home country, her representation of the victims of Colombia’s warring communities is destined, whether intentionally or not, for Western consumption. Its consumers include not only public art museums and spaces that exhibit and support her work, but also the commercial markets that trade in, and on, her art. Although it is not usual for criticism to engage with the market side of artistic output, it is nevertheless important to acknowledge that art and commerce are in an intricate, and often opaque, symbiotic relationship. The friction generated by this conflict of interest is particularly acute for an artist whose work is politically orientated and engaged, and which articulates violence and the depth of human suffering. Can the artistic expression of anguish be given a price within capitalism and traded for profit by the world’s most powerful gallery owners? If not a contradiction in itself, this sort of artistic collaboration with market forces must be, at the very least, problematic.

The bipartite nature of this essay is intended to highlight not only the contradictory nature of today’s art industry, but also the sorts of dilemma that a politically engaged artist living in both the creative and commercial worlds might have to face in order to function within these different realms. This approach entails a somewhat wider critical perspective than is usual, since without distinguishing clearly between the different contexts in which a particular art work is seen and/or traded, it is all too easy to lose sight of the crucial role played by the politics of location and their dynamics.1 Taking as examples those of Salcedo’s works inspired directly by the 1985 siege of the Palace of Justice, my paper aims, in the first place, to investigate how the reception of her art in the West might be typical of the way in which the Western art world habitually consumes and appropriates works from the ‘Third World’. It is my hope also to shed light on how women artists, or indeed any female cultural workers, from politically troubled countries can make successful careers for themselves within mainstream Western art institutions. The high point of Salcedo’s artistic output so far, Shibboleth, shown at Tate Modern in 2007, further illuminates the ways in which ‘Third World’ artists can be accommodated and consumed within a predominantly Western cultural discourse.

This is not, of course, to suggest that Salcedo is a typical artist whose professional record can be taken as any sort of examplar of a ‘Third World’ woman trying to make her way in the Western art world. Salcedo’s career is in fact anything but typical. No Latin American artist has managed what she has achieved in such a short amount of time in high-powered Western art establishments, both public and commercial. Nevertheless, her political interaction with Western institutions provides an illuminating example of how it is possible for an artist operating between two worlds to successfully negotiate, and secure for herself, a position of cultural prominence. Needless to add, it is never easy for any independent researcher outside the closed circle of cognoscenti to map clearly the intricate networking and social-relation mechanisms within the contemporary art world, especially as these often require insider knowledge and special access. The best that can be done is to sketch out some significant historical junctures at which certain key players and institutions have helped to shape and impact on an artist’s development.

In common with many ‘Third World’ artists who go to the Western centres of contemporary art for training, Salcedo completed her postgraduate studies in New York – an experience that not only provides graduates with opportunities for further professional development, but also frequently facilitates personal networking and access to art institutions in general. Having finished her masters degree (in sculpture) at New York University in 1984, Salcedo took a further eight years to make her institutional debut in the West, namely the group show ‘Currents 92: The Absent Body’ at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston in 1992.2 The following year she appeared in a group show at a leading New York commercial art gallery, Brooke Alexander.3 Before 1993, her exhibition record was exclusively in Bogotá; after that point, she exhibited almost uniquely at Western institutions. The year 1993 also saw her feature in the special section of the 45th Venice Biennale, ‘Aperto 93: Emergence/Emergenza’.4 Given that the biennale represents the largest gathering of art specialists anywhere, appearing there placed her work for the first time on the world stage.

It did not take Salcedo long to be awarded her first solo show, ‘La Casa Viuda’, at Brooke Alexander in 1994, followed by another at White Cube in London in 1995. Successive exhibitions in both New York and London, the two most important centres of contemporary art of the time, indicate that she had secured a solid bridgehead in the commercial market. In terms of her large furniture works, the curators of biennial exhibitions such as the Carnegie International 1995, curated by Richard Armstrong, were particularly supportive of Salcedo’s work, providing her with the space she needed to show the work to its best advantage. A new group of furniture pieces, all from 1998, were then shown at the São Paulo Biennial of that year, and were seen by Anthony Bond, who would curate the first Liverpool Biennial the following year and who asked that all of the pieces be exhibited in Liverpool.5 The international nature of these biennials earned for Salcedo an exposure as extensive as a string of solo exhibitions would have achieved.

By the end of the 1990s, Salcedo’s work had entered the circuit of Western public institutions, winning the support of respected curators such as Dan Cameron and Charles Merewether, who consistently drew attention to her output. The late 1990s witnessed a series of exhibitions of her Unland works at the world’s most prominent art museums: ‘Unland/Doris Salcedo’ at the New Museum of Contemporary Art in New York and SITE Santa Fe in New Mexico in 1998 and then at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 1999, and ‘Art Now 18: Doris Salcedo’ at the then Tate Gallery in the same year. By the end of the decade, Salcedo was well established in both the commercial market and the public sector, and moving at ease back and forth between the two. It was the Tate exhibition, however, that foreshadowed and facilitated her Turbine Hall commission at Tate Modern in 2007. Despite occupying a small area within the gallery, the Art Now series at the Tate, devoted exclusively to younger and emerging artists, represents an important venue to showcase new talent. It is a much coveted space and a golden opportunity for any aspiring artist to acquire the kudos that automatically goes with having been exhibited at the Tate. Entering the Tate collection must have been a turning point in Salcedo’s career, especially given the strong support of its director, Sir Nicholas Serota. What is remarkable, in such circumstances, is that within a few years, she was to be selected for a high-profile project of such magnitude as the Turbine Hall commission.6 The new millennium saw a significant change in Salcedo’s working methods. Unlike her previous pieces, which had been closely related to the political and social situations in Colombia, her works during the period before she took up the Tate commission were primarily site-specific projects, where art and architecture were well integrated into the specificity of the locality in question.7 These included the much acclaimed installation of 1,550 wooden chairs at the 2003 Istanbul Biennial, Neither at the White Cube in 2004 and Abyss at the Castello di Rivoli in Turin in 2005.

Despite shuttling back and forth between Bogotá and the West, Salcedo has not interrupted her output over the last two decades, overcoming both the inconvenience and the discrimination involved in leading this sort of double life, and she has, above all, chosen to continue living in her home city.8 This is in stark contrast to a substantial number of other contemporary artists not born in Western Europe or North America who have chosen to move to one of these areas in order to pursue a better career.9 It is in this sense that Salcedo’s career is untypical as far as ‘Third World’ artists are concerned. The fact that she had started out very early in her career under the aegis of a New York-based dealer must, one supposes, have provided her with the art-world networking and access links necessary to ensure future success, which an artist based solely in Bogotá could not possibly have been able to take advantage of.

Salcedo also is unique in the way in which she has so far chosen to work. In comparison with the majority of artists of her generation, she has produced very little in terms of quantity.10 Each of her works is a unique piece, and it is not her habit to work in editions. During the 1990s, the worn shoes of the Atrabiliarios series and the cemented furniture series hardly amounted to a very voluminous output, while in the millennium decade she did mostly public projects that were not particularly saleable. Two exceptions were the 2004 installation Neither, exhibited in the London commercial gallery White Cube, which was sold to a Brazilian collector, and the reinstalled piece known as Abyss at the Castello di Rivoli. Though it is customary for artists in such circumstances to put their working drawings or sketches on the market, Salcedo has so far made none available for sale.11 Given that a large number of her works from the 1990s have entered public collections, there are very few pieces left to circulate round in the market, which leaves demand for her work high and constantly unsatisfied. How this situation is likely to develop is something to which we shall return later in this paper. Having briefly contextualized Salcedo’s production in relation to the Western art establishment, both public and commercial, over the last two decades, it is time for us now to take a closer and more detailed look at her output, with the aim of better understanding why her work is so sought after, and what makes her specific contribution to contemporary art so original.

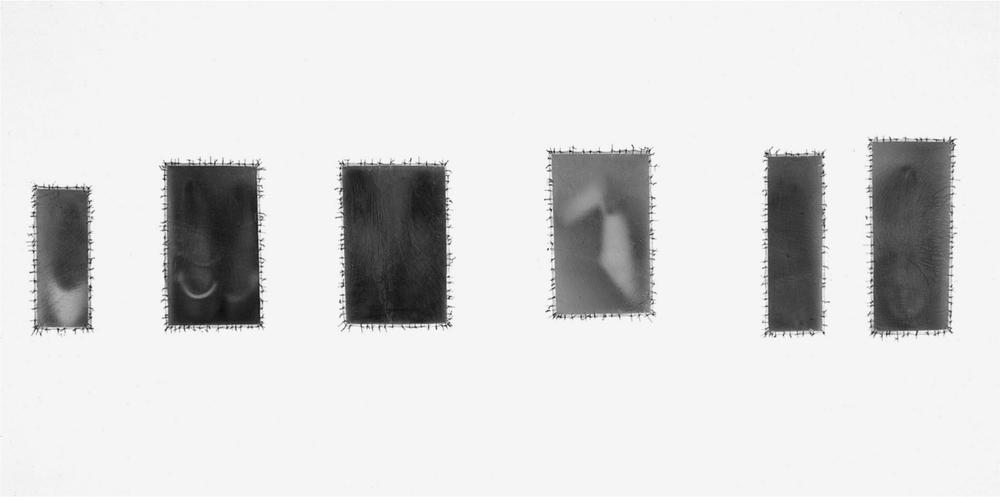

1 Doris Salcedo, Atrabiliarios, 1992–3, wall installation with sheetrock, wood, shoes, animal fibre and surgical thread in ten niches with 11 animal fibre boxes sewn with surgical thread. Photo: Robert Pettus, courtesy Alexander and Bonin, New York.

Since the late 1980s and throughout the 1990s, Salcedo based all of her work on the first-hand evidence she collected during her many field trips into the countryside of her native land, places of deadly civil conflict such as abandoned villages and sites of mass graves and wholesale slaughter. Although civil war has never been officially declared as such, the civilian population of Colombia has been constantly subjected to indiscriminate violence occurring as a result of the internal conflicts between different political parties and factions, paramilitaries, guerrillas and drug dealers. Employing, indeed recycling, personal domestic objects used by the victims themselves, Salcedo makes these scraps and fragments from everyday life speak for the absent body and the missing person and the pain and sorrow that their absence brings.12 In one of her most famous installations, Atrabiliarios [1], worn shoes, mostly from female victims, are placed in boxlike niches inserted directly into walls. The niches’ fronts are sealed with translucent animal fibre, stretched taut with surgical thread. The used shoes, which stand in a relationship of synecdoche with their absent owners, are the sewed and sealed memory and mourning that the survivors have to carry around with them together with their emotional wounds.

In another installation, La Casa Viuda, a series of five works made between 1992 and 1995, used doors and other domestic furniture such as bed frames and stools have bones, zippers and fragments of clothes inserted into them. The title of the work – in English ‘the widowed house’ – already evokes the image and association of a bereaved woman alone with her loneliness and her grief. The delicate insertion of human traces into the furniture further works to strengthen its visual complexity; the intimacy of the zippers and fragments of personal clothing, being interwoven with the domesticity of used objects, inevitably invites association with their absent users. But in Salcedo’s work, such emotional associations of loss and memory are always very subdued and carefully controlled. Even in La Casa Viuda VI [2] where a child’s metal bicycle seat is blocked by one door and fixed to another, the reference to a child’s suffering and bereavement is understated and only indirectly referenced. The potency of this work lies in the ambiguity and understatement of the representation, while Salcedo’s use of everyday objects is charged with strong emotional associations.

2 Doris Salcedo, La Casa Viuda VI, 1995, wood, bone, metal in three parts: (1) 190.2 × 99.1 × 47 cm; (2) 159.7 × 119.3 × 55.8 cm; (3) 158.7 × 96.5 × 46.9cm. Photo: D. James Dee, courtesy Alexander and Bonin, New York.

But for her two major works related to the events in the Palace of Justice in 1985, Salcedo was forced to abandon her previous practice of employing objects actually owned and used by the victims. Forced, that is, in the context of her urgent need to ensure the survival of the collective memory of the tragic events that had traumatized an already damaged country – at a time when the government had been going out of its way to erase all possible traces of the events by destroying each and every object left in the burned-out building.13 The two works, in their use of chairs as both images and objects, represent therefore a significant departure for the artist, both emotionally and artistically. In her previous work, Salcedo set out to identify with, and substitute herself for, the victims. As she herself stated:

I try to learn absolutely everything about their lives, their trajectories, as if I were a detective piecing together the scene of a crime. I become aware of all the details in their lives. I can’t really describe what happens to me because it’s not rational: in a way, I become that person; there is a process of substitution.14

In cases where objects are, as it were, imprinted with their previous owners, the metonymic substitution might be easier to imagine and to sustain. What, then, is the role that the artist plays, or more precisely that Doris Salcedo plays, in a work of art created from her own resources rather than from other people’s objects, and claiming to make specific reference to contemporary historical events? In her own eloquent essay commenting on and explaining the work in question, Salcedo talks of the role of the artist as interlocutor, using what she calls ‘active memory’ to build a bridge between the solitary remembering of individual victims and the collective memory of a community.15 For Salcedo, ‘active memory’ presupposes two basic actions, that is, remembering (or recording) and narrating:

To remember is to make a deliberate effort of memory. But the act of recalling past facts without the capacity to narrate them condemns memory to oblivion. Active remembering is, therefore, above all a narration. If we limit memory to the act of remembering, we convert it into a solitary memory: the traumatised victim remembers in solitude. As a narrative act, [however,] memory seeks an interlocutor and in that way transforms itself into social or collective memory.16

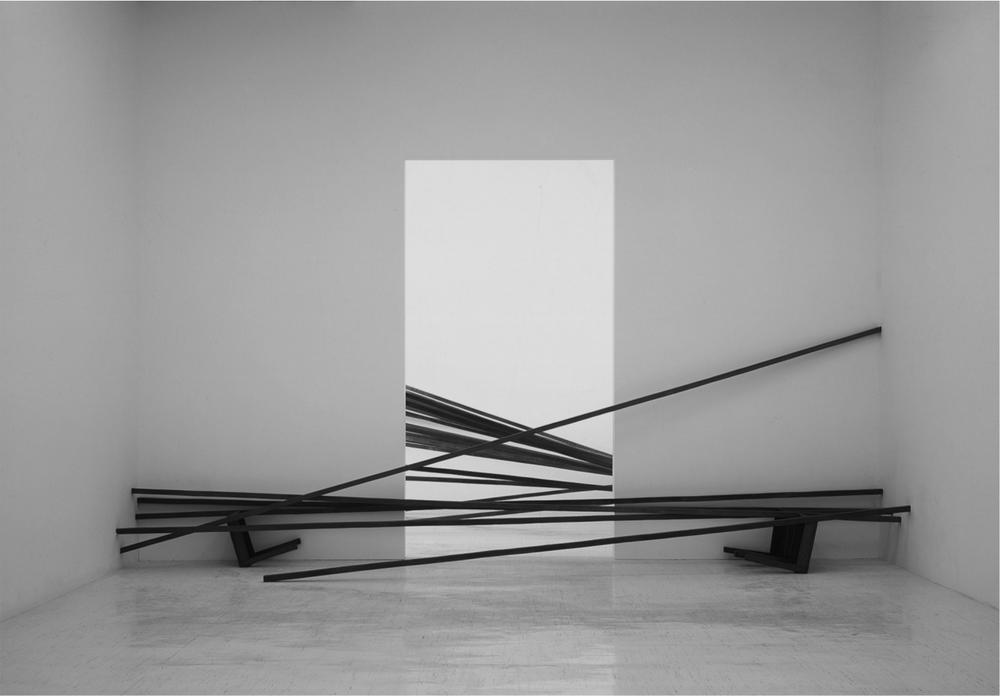

The events of the siege of the Palace of Justice in 1985 gave Salcedo the impetus to produce two major works. The first, Tenebrae, Noviembre 7, 1985 [3], was exhibited at the Camden Arts Centre in London in 2001, and then in Documenta 11 at Kassel in 2002. The second, more of a conceptual intervention than an art object, took place at the very location of the event it commemorates. In both cases, chairs supply the central metaphor. In Tenebrae (literally ‘shadows’), an entire room is blocked off with elongated rods and upturned chairs made of metal. A closer inspection reveals that what appear to be metal studs preventing visitors from approaching actually are chair legs. The ambiguity of the relationship between the chairs, their legs and/or the blocking rods, and the space thus defined and blocked off, is a function of the (post-) minimal sculptural language that Salcedo chooses to use for her work. The chairs are of a uniform shape and size, as are the standard two-foot-by-two-foot blocking studs. Abstract though the work is, some sense of violence emanates from it, but to what extent can minimal abstraction give expression to the specific realism and ‘content’ that the artist implies by the specifically dated title? Can the horrific violence of lived experience be conceived of, or dealt with, effectively in abstract terms? The sense of violence that the space evokes is confirmed, or perhaps strengthened, by a number of pieces of crushed chairs placed outside the room (called Noviembre 6), an installation that is further expanded in the Documenta exhibition [4]. Like the chairs and the studs in the room, these are made of stainless steel, lead, wood and resin, but they have been violently crushed together by some unspecified force. Some are, like a battered body, heavily disfigured and barely recognizable as chairs. Others, again like a battered body, retain the scars of the brutality that has been inflicted on them.

3 Doris Salcedo, Tenebrae, Noviembre 7, 1985, 1999–2000, lead and steel in thirty-nine parts, dimensions variable. Photo: Stephen White, courtesy Alexander and Bonin, New York.

Although the violence undergone by the crushed chairs is clear in Salcedo’s work, the question that remains is how far these objects can be made to relate to the experience of the suffering of the Colombian people, especially in the eyes of a Western European audience? It would be less problematic if we could see the chairs simply as a representation of violence in general, but the artist somehow hints at a more specific reading of them by giving the composition the definite title she does.17 The question is therefore made more complex than it appears to be at first sight. Over the past decades, despite her growing international reputation, Salcedo has seldom exhibited inside Colombia. Her works, even if they are not deliberately designed for exhibition and consumption in the West, have so far mostly been seen only outside the social context that actually inspired them.18 It is ironic, given this decontextualization, that the interpretation of Salcedo’s work in the West, critical or otherwise, is always coloured by an emphasis on the fact that the artist is from Colombia and that her work deals with the living situation of that particular country – an emphasis, it must be said, that is partly of Salcedo’s own making and of which she herself is very much aware.19 This Western orientation, perhaps even appropriation, of her work, as well as an awareness of the political situation in Colombia are, in other words, two important background factors that need to be taken into account in any interpretation of these chairs.

4 Doris Salcedo, installation view of exhibition at Documenta 11, Kassel, 2002. Photo: courtesy Alexander and Bonin, New York.

Viewing these works in a Western art space in the specific way the artist’s titles and the gallery information seem to want us to see them, raises, therefore, some particular problems. Encountering the works without knowing anything of either the artist or her past compositions is an entirely different experience from that of seeing them with knowledge of her background and particular biographical details. When, for example, the British art critic Adrian Searle asserts that, ‘It is hard to look at Salcedo’s work and not think of real disappearances and kidnapping in her native Colombia’,20 he is clearly taking prior knowledge for granted.

What complicates matters even further are differences in the actual viewing contexts. One need only, for instance, compare the visitor responses that the different conditions at the Camden Arts Centre and at Kassel elicited. At Camden, a typical ‘white cube’ gallery from which the outside world is completely excluded, the works occupied the whole space, which has the effect of giving the visitor a more concentrated, if not controlled, and unified atmosphere to contemplate. In contrast, at the Fridericianum Museum at Kassel, Salcedo’s work was shown in a huge room that it shared with the works of Leon Golub. The enormity of the space made Tenebrae and its accompanying installation of chairs look quite lost. The nature of Documenta as an art spectacle showing a multiplicity of works by a huge number of different artists, with the constant flow of hundreds, if not thousands, of visitors crowding in to the exhibition space, made any specifically Colombian reading of Salcedo’s work quite impossible (something incidentally that appalled the artist herself). It is difficult, if not impossible, to imagine that visitors could have the time for reflection necessary to relate these works to their specific sociohistorical context, as a proper appreciation of the pieces requires.

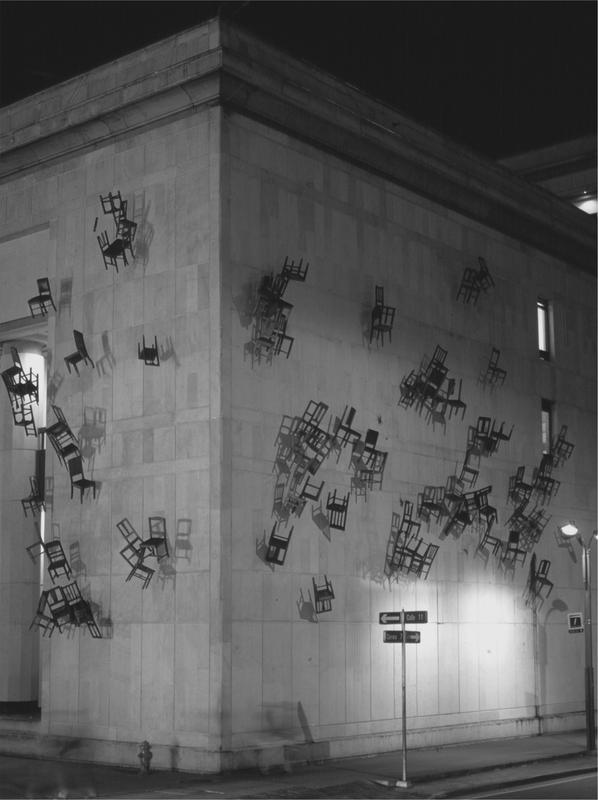

If the political context of Salcedo’s work might thus be sometimes lost on its Western European audience, quite the opposite is true in contexts where the audience happens to be exclusively Colombian. In Noviembre 6 y 7 [5], the second of two works commemorating the tragic events of 6 and 7 November 1985 with which we are concerned here, Salcedo chose the precise time and the actual location of the event to make her commemorative act of remembrance. At 11:45am on 6 November 2002, seventeen years after the siege of the Palace of Justice, empty used chairs suddenly started to appear, descending slowly from the roof down the stone facade of the south and east walls of the palace, an act that ended at 2:30pm on 7 November, at precisely the same time as the original siege was brought to a brutal conclusion by the building being set on fire and many innocent lives being lost. These wooden chairs, 280 in total, were intended to cover the entire facade of the palace; some of them were broken, others aged with the imprint of the passing years.21

Chairs are everyday objects, banal and ordinary yet intimate. Most of us spend a large proportion of our waking lives on them. Empty chairs provide us with no helpful definition of, or clue to, the social relationships between them and their absent sitters, but what they do effectively is evoke the people no longer sitting on them, or rather the people who should still be sitting on them. In Tenebrae, the distortion of the chairs, upturned and with their grossly extended limbs, seems to serve as an additional reminder of the physical violence – and torture – undergone by those who formerly sat on them. The chairs chosen by Salcedo for her conceptual installation are individual domestic objects belonging to interiors. Several chairs set in groups evoke people gathering together, a family eating, for example, or staff assembling for an office meeting. A large number of chairs – several hundred – bring to mind an audience, a theatre or cinema audience, perhaps, and a public spectacle. Chairs can therefore be seen as objects of transition between the individual, the private and the domestic, on the one hand, and the collective, the public and the spectacular on the other. To hang chairs from an outside wall is to put outside what belongs inside – in other words to turn the inside out. The image thus created is not only one of a cascade or waterfall of chairs, but also one that evokes a large number of people trying to escape to safety from the impending disaster inside. The tragedy consists in the fact that what has actually been saved are the chairs themselves rather than the people sitting on them.

Like Ionesco’s more celebrated chairs, Salcedo’s pieces are potent symbols of dehumanization. This ephemeral art event marks out the palace as a place of permanent memory, providing a public spectacle of empty seats that is intended to prompt passers-by to relive their own memories of the tragic events, as well as to show solidarity with the victims’ families and survivors in the loss and emptiness they have ever since had to endure. No less important is the fact that the Palace of Justice is located in the Plaza de Bolivar, Colombia’s principal ‘space of public appearance’, as Hannah Arendt once called ‘the symbolic realm of social representation’.22 The very publicness of the Plaza de Bolivar gives any private act committed on it an immediate political significance that is inevitably collective. By appropriating the walls of the most public square in her country’s capital, Salcedo staged a silent protest in full public view, silently echoing the then government’s own complicit silence and that of the previous authorities, whose bungling inhumanity brought about the initial tragedy.

5 Doris Salcedo, Noviembre 6 y 7, 2002, installation, Bogotá. Photo: Oscar Monsalve, courtesy Alexander and Bonin, New York.

‘To live’, as Benjamin famously said, ‘means to leave traces’.23 For those, however, whose traces are deliberately erased by illegitimate or indiscriminate force, their very existence is in danger of being forgotten unless they find a voice with which to express their violation and disempowerment. It is in such cases that the artist can fulfil the role of interlocutor, and can lend (rather than give) a voice to those whose suffering has made them mute, and whose complicitous fear paralyses their capacity to act for themselves. In this way, private grief imposes itself on public consciousness, the invisible is made visible, the absent is made present, and the forgotten is remembered. The domestic becomes national, and the national, international. To view Salcedo’s work outside its national boundaries, however, poses a number of problems and dilemmas for Western eyes: to what extent does our gaze make us complicit onlookers, content to nod in sympathy at abuses committed by the Other on the opposite side of the world? And how far – dare one ask? – is Salcedo’s critical success in the West a function of our need to salve our own liberal consciences?

This question has become even more relevant since she was commissioned to produce the eighth Unilever Series installation in the Turbine Hall of Tate Modern in 2007. She was the first artist from Latin America to be invited to fill such a prestigious space, and only the third female artist to be so honoured. Tate Modern is, arguably, one of the two most prestigious modern and contemporary art museums spaces in the world, on a par with the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Salcedo’s presence in such a high-profile commission in a space of high visibility has undoubtedly brought her to a position of considerable prominence.

Salcedo’s work at Tate Modern, Shibboleth, consisted of a 167-metre-long crack that ran the length of the vast Turbine Hall. To those entering the museum, the fissure was barely visible. But as it zigzagged across the floor, it grew progressively more visible, wider and deeper until finally, when it reached the centre of the space, it had the proportions of a forklike trench. Gradually thereafter, the cut again became less and less visible, until it finally disappeared at the far end of the hall. Along the length of what looked like an earthquake fault line, a tunnel effect was created by its sub-surface interior being covered with plastered wire mesh, the structure of which was reminiscent of containing fences around, for examples, prisons or concentration camps. The biblical reference in the title Shibboleth does, in fact, refer to a process of separation, to the password that serves to separate the sheep from the goats – to distinguish the supposedly superior Gileadites from the supposedly inferior Ephraimites.24 The work was, however, popularly known as the ‘crack’, or ‘the Tate crack’.25 To create a crack of these proportions was, of course, no easy task. Leaving aside the technical difficulties involved and the inevitable health-and-safety concerns, Shibboleth was a direct intervention into the structure of the architectural space of Tate Modern – one might even say an attack on its very structural integrity.

Shibboleth thus not only literally tears open the floor of Tate Modern, but also symbolically undermines the value system and structure of all that this celebrated institution embodies. Salcedo has not been reticent about telling her public exactly what she considers the meaning of the work to be: ‘If I as a Third World artist am invited to build one of my works in this space, I must bring them what I am, and the perspective of what I am. I think the space defined by the work is negative space, the space that, ultimately, Third World persons occupy in the First World.’26 Salcedo specified what this perspective might be in her proposal statement for the commission: ‘Shibboleth … addresses the w(hole) in history that marks the bottomless difference that separates whites from nonwhites. The w(hole) in history that I am referring to is the history of racism, which runs parallel to the history of modernity, and is its untold dark side.’27 She further stated that:

This piece is inopportune…. Its appearance disturbs the Turbine Hall in the same way the appearance of immigrants disturbs the consensus and homogeneity of European societies. In high Western tradition the inopportune that interrupts development, progress, is the immigrant, the one who does not share the identity of the identical and has nothing in common with the community.28

The crack in Shibboleth clearly represents a separation and a fault-line running through the foundations on which our sociopolitical life and artistic culture are constructed. What appears to be solid is undermined by a basic and structural fault. Whether or not it represents racism, as defined by Salcedo, is, however, open to question, since no racial interpretation is inherent in the crack. As with any effective art work, it is open ended so that any one of a wide range of schisms can be read into it.

For all its ambiguity, one thing that is crystal clear is the work’s relationship to its host institution. The physical violence that the crack imposes on the very fabric of this high-profile building is unprecedented. No other art work has so completely broken open an art museum, so forcibly obliged its visitors to look downwards instead of sideways or upwards, and left such a permanent physical scar on its floor space as Shibboleth has done. As British journalist Rachel Campbell-Johnston put it: ‘Tate Modern, a triumphalist monument to our modern Western culture, is quite literally riven in two by an artwork that provokes us to question the very foundations of our ways of thought.’29 Campbell-Johnston’s reflection is not untypical of studies on Salcedo’s art. As with all of her public projects, Salcedo has provided, for Shibboleth, a clear statement analysing exactly what she had in mind at the start of the project. In this way, she is able, from the outset, to direct, to a certain extent, the critical discourse to which her work is to give rise. The racism discourse is no exception. In today’s climate of political correctness, the racial interpretation of the work is not only to be tolerated but even actively, and willingly, embraced. As Sir Nicholas Serota declared at the press conference inaugurating the work: ‘There is a crack. There is a line and eventually there will be a scar. That is something that we and other artists will have to live with.’30 In contrast to those missing Colombians whose trace, erased by illegitimate and indiscriminate force, but restored by Salcedo in her early works, the scar that the artist has been able to leave at Tate Modern is well nigh impossible to erase. Not only that, but it is actually welcomed by the powers-that-be in the Western art establishment.

Indeed, the way in which Tate Modern went out of its way to accommodate the artist was little short of extraordinary. It is clear in retrospect that the actual politics of the production of Shibboleth were embargoed as confidential and completely sealed off from any public scrutiny.31 It might be understandable – though not necessarily acceptable – if details of the actual financing of the commission were kept secret. But even straightforward technical questions such as how the piece was constructed, and how deep the crack actually was, remained resolutely unanswered. At the commission press conference, the director of the museum, the curator and the artist pointedly avoided responding to such questions from increasingly frustrated journalists. On-site staff were apparently also instructed not to disclose any details of the construction of the work itself, even though some felt proud enough to confide: ‘Of course, I know how it was made.’ This intriguing lack of transparency turns out, on investigation, to be a condition imposed by the artist herself. Even though talking about methods of production and how art is actually created has been an integral and ubiquitous part of artistic discourse throughout the centuries, Tate Modern felt able to turn a blind eye to its own remit as a public educator and complied. One would have thought that Tate’s worldwide reputation would enable it to impose its own conditions rather than accept those of the artists it commissions. That it was willing to go to such lengths to accede to Salcedo’s requests is an eloquent testimony to the power relationship between the self-proclaimed ‘Third World’ artist and her ‘First World’ art institution. Even Salcedo herself expressed surprise at Tate Modern’s willingness to grant her and her work their unqualified approval, and went on record as saying – not without gratitude, one suspects – that ‘It’s quite extraordinary that the Tate would accept this work – there are not many museums in the world that would dare.’32

However true this may be, it is undeniable that the Tate commission launched Salcedo into a stage of her career when she could command the same sort of global attention that any comparable Western artist would have enjoyed. Despite this, and although she had long benefited from the support of a circle of art-world insiders (museum directors, critics and curators included), the media coverage of her work and the critical writing it inspired had remained surprisingly limited. This had nothing directly to do with the quality of her work, but more with the hegemonics, economic and cultural, of the Western art world. The art support systems in the West, the scope and scale of the art market, the number and standing of the curators and critics, the importance of art magazines, journals and books are far more developed than any other ‘Third World’ country could possibly sustain. British artists such as, for example, Rachel Whiteread, an approximate contemporary of Salcedo’s, fare much better in the sense that their work immediately generates scores of notices and reviews, both locally and internationally.33 With the Turbine Hall commission, however, Salcedo suddenly became a household name in the West, and this success reverberated throughout the ‘Third World’.

Salcedo’s new-found popularity in the Western press and art establishment has brought with it a new style of critical writing that raises certain general methodological problems concerning the accessibility of works of art. Given, for example, the ephemeral nature of Salcedo’s Noviembre 6 y 7 performance work that took place in Bogotá, far away from any contemporary art centre or location, few Western curators or critics could actually have seen the performance themselves.34 The need, however, among some critics to produce a critical narrative of this sort of performance means that they often work from secondary material and at second hand. The same photos and the same performative details – both, one assumes, supplied ultimately by the artist – are produced over and over again by critics who have no means of properly investigating the political and cultural contexts of the actual site where the event took place. Just how essential such considerations are when articulating critical responses to art is well illustrated by the case of Whiteread’s Holocaust Memorial in Vienna, which no self-respecting critic would dream of writing about without having been to Austria and seeing the work first hand in situ.

The Western art establishment that extended such a warm welcome to Salcedo is not of course exclusively composed of public art institutions. In anticipation of the high-profile exhibition of Shibboleth, her agent in London, White Cube, opened a solo show of her work on 15 September 2007, three weeks ahead of the opening of the Tate Modern commission.35 The timing could not have been more strategically chosen or more commercially orientated. Given the upcoming exposure, it was only reasonable to assume that Salcedo’s reputation in the art world would rise significantly and so, naturally, would her market value.

The White Cube show must have posed a particular problem for an artist whose political commitment has always been part and parcel of her work. How comfortable she is in a relationship with the high priest of art capitalism that White Cube represents must remain a matter for conjecture. Nonetheless, eight medium-to-large furniture pieces, not to mention a number of smaller cemented chairs, were crowded into the modestly sized Hoxton Square space. Rarely had the gallery displayed works in such a crowded situation. In terms of quantity and quality, what could easily have been a museum exhibition in fact turned out to be a sales opportunity, given the fact that the supply of Salcedo’s earlier furniture pieces was so limited and demand for it consequently so high. The five older pieces that had been bought back from private collectors by White Cube could therefore be seen as a marketing strategy designed to secure a market monopoly. As one critic anonymously remarked of the gallery owner Jay Jopling: ‘He’s now the one who owns everything; he can give you any price for any piece.’36 Equally problematic were the three new furniture pieces presumably produced specifically for the sale. Although Salcedo has never drawn any sort of line under the 1990s furniture pieces,37 it was something of a surprise to see these pieces resurrected, as it were, and reappearing on the market after a break of ten or so years. With each one being potentially worth half a million pounds, if not more, it is easy to see what was at stake. To quote one critic, again anonymously: ‘Of course, artists can do whatever they want to; they could produce 100 more pieces, but in a way, nobody would respect that. It was a little unexpected seeing again new pieces of the same series that had already been concluded.’38

The issues (political and otherwise) raised by Salcedo’s shows at Tate Modern and White Cube can perhaps most usefully be viewed in the context of the problematic relationship between public and commercial enterprise under neoliberal capitalism, a force unleashed under Britain’s Thatcherite government when public institutions could no longer function properly without being heavily reliant on private (including commercial) money.39 Although Salcedo’s commission came under the banner of the Unilever Series, the sponsorship money, which amounts to some quarter of a million pounds each year, is unlikely alone to have met the full production costs.40 To quote Achim Borchardt-Hume, the Tate curator who coordinated the commission: ‘It’s not that sponsorship is the same thing as the project budget; it’s not the sponsor who pays for a project, nor did Unilever pay for the whole Turbine Hall commission. It’s rather that Unilever made the commitment to pay a certain amount of money in support of the project, but then the project budget is something else…. Obviously Doris’s work has super-high production costs. It’s not a low-budget production from the outset. There can only be certain galleries, and certain mechanisms of production, that could make that possible.’41 Precisely what the ‘certain mechanisms of production’ were that actually made Salcedo’s commission possible is, however, destined to remain a mystery. Who contributed, and how much, towards the cost of producing Salcedo’s work? Despite being a model of helpfulness and frankness in other respects, Borchardt-Hume resolutely declined to reveal any figures concerning the actual cost of Salcedo’s commission or any sponsorship deals involved in it. Nor was my question on the same topic filed with the Freedom of Information Office Group in the Director’s Office at Tate Modern any more revealing. Not only did the Tate refuse to disclose the total budget, they also declined to give any detail of other additional funding. It stated:

Tate cannot disclose the amount of budget for individual installations…. The amount of the budget for Shibboleth has been withheld under section 43(2) of the Freedom of Information Act,… as we believe it would prejudice Tate’s commercial interests to release this…. The additional support: the FoI group considers that to supply this information would prejudice the commercial interests of Tate in relation to those sources, and that the public interest in releasing this is outweighed by the public interest of Tate’s continued ability to work with these sources.42

The Tate’s non-reply is a model of non-information, if not intellectual dishonesty, and surely makes a mockery of the so-called Freedom of Information Act.

It is not impossible to imagine the Shibboleth commission, having been first produced and fabricated in Bogotá and involving many staff over several months, and then being shipped to London to be installed on site, over a matter of six or so weeks, by Salcedo and a Colombian and local crew consisting of scores of people working in teams,43 incurring costs that would easily overshoot the million-pound mark. Since no private collector could be expected to support a project so obviously designed for the exclusive glory of Tate Modern,44 Salcedo’s commercial agents in New York and London seem likely to have provided the only mechanism whereby the commission could secure the extra finance it needed. If this were the case, it would come as no surprise to see these galleries taking a direct and vested interest in enhancing the reputation and market price of such an artist. It is, moreover, no secret in the art world that commercial dealers often have a financial role to play in funding the appearance of their artists at international biennials.

The intricate symbiotic relationship between the Tate, a public institution, and commercial enterprise in the shape of the superstar gallery White Cube reveals a great deal about the dynamics of today’s art world and its often opaque market mechanisms. In particular, the lack of transparency surrounding the politics of the production of Salcedo’s Shibboleth commission brings to the fore the problematic nature of public and commercial ‘cooperation’. Is it a happy marriage based on the common interest of producing a landmark work of art that serves the best interests of the Tate’s wide public? Or is it perhaps a different sort of partnership, one that, while ostensibly serving the so-called ‘public interest’, is actually more like private enterprise in disguise, advancing the commercial interests of White Cube and – dare one speculate? – those of the artist herself?

The politics of the production of Salcedo’s Shibboleth commission are no doubt closely bound up with those of the artist and those of Western art institutions, public as well as commercial – a topic rarely broached in the critical literature. While as a ‘Third World’ artist, Salcedo has produced work, and Shibboleth above all, that carries with it a critical political agenda vis-à-vis the power structures of Western art institutions, this does not apparently prevent her, at a personal level, from being deeply involved and implicated in the very power structures that she is criticizing. This paradox is perhaps inevitable as long as the status quo remains unchanged, with the current power hierarchy in the contemporary art world still dominated by Western institutions. After all, Salcedo’s universal visibility in terms of global reach can be achieved only if she works and exhibits with powerful Western galleries, and her critique of existing structures is possible only in so far as it continues to be sanctioned by institutions such as Tate. Even if the critique is somewhat muted, Salcedo’s work itself has certainly secured for her a prominent place in the contemporary art world. Few artists have so relentlessly devoted themselves to the problematics of human violence as she has. With her newly branded status as a Tate-commissioned artist, her voice can now be heard loud and clear.

In negotiating her way between the two worlds of Colombia and America / Western Europe, Doris Salcedo has certainly made her mark and changed the artistic landscape for the better. She has forged for herself a rewarding career both in terms of aesthetic achievement and worldly success. Not all works of art and practices, however, can be accommodated to capitalist market interests to the same degree or with equal legitimacy. Some, in particular those who exploit the suffering of fellow human beings – and the more so if these are innocent women – are inevitably drawn into the byways of the moral maze. They acquire a privileged status that makes them special and at the same time vulnerable. If, for whatever well-intentioned reasons, this sort of work becomes the victim of financial manipulation, then not only the art and the artist who creates it, but also the public for whose consumption it is intended, are all thereby compromised. Only the future will reveal how far Salcedo will have been able to reconcile political belief with commercial expediency.

I would have liked to express here my gratitude to all those who were kind and cooperative enough to speak to me as I prepared this essay, but unfortunately the requirements of anonymity prevent me from acknowledging their contribution more explicitly. An earlier and shorter version was published under the title of ‘Scars and Faultlines: The Art of Doris Salcedo’ in New Left Review, vol. 69 (May/June 2011), pp. 61–77.

1 Elizabeth Adan, for example, treats the spaces of White Cube and Tate’s Turbine Hall as if they were exactly the same thing, calling both ‘quintessentially “First World” art institutions based in London’; see ‘An “Imperative to Interrupt”: Radical Aesthetics, Global Contexts and Site-Specificity in the Recent Work of Doris Salcedo’, Third Text, vol. 24, no. 5 (September 2010), pp. 591–2.

2 The biographical data are derived from the Phaidon monograph, Carlos Basualdo et al., Doris Salcedo (Phaidon: London, 2000). This publication contains the most comprehensive account available of Salcedo’s exhibiting history up to the time it was published in 2000.

3 Salcedo started to work with Brooke Alexander gallery in 1992, and then moved to Alexander and Bonin in 1995 when Carolyn Alexander, a partner in Brooke Alexander, left to form her own gallery with Ted Bonin (former gallery director at Brooke Alexander) in 1995; email correspondence with Carolyn Alexander, 20 July 2010.

4 Although there were a hundred or so artists from many different countries in ‘Aperto 93’, Salcedo came to notice by securing a half page of press coverage in the established art magazine Flash Art: ‘Doris Salcedo’, Flash Art, vol. 26, no. 171 (Summer 1993), p. 97.

5 Telephone interview with Carolyn Alexander, Salcedo’s New York agent, 18 October 2010.

6 Although the commission was officially inaugurated in October 2007, the actual process started as far back as April 2006; interview with Achim Borchardt-Hume, then curator at Tate Modern, 28 November 2007.

7 For her work, Salcedo used to travel to areas of high violence outside Bogotá, but when the security conditions in Colombia deteriorated, she was forced to change her working habits; interview with Salcedo, 20 September 2003.

8 It was reported in 1995 that when her work was in transit from Colombia to the United States, the suspicion was that it was in some way related to drug trafficking, and it was accordingly destroyed by the customs; see ‘Artwork Destroyed’, Los Angeles Times, 4 November 1995, Part F, p. 2.

9 Chin-tao Wu, ‘Biennials sans frontières’, New Left Review, vol. 57 (May/June 2009), pp. 107–15.

10 Hans-Michael Herzog made similar comments in his interview with the artist, ‘Conversation between Doris Salcedo and Hans-Michael Herzog’, trans. Camilla Flecha, Cantos Cuentos Colombians: Arte Colombiano/Contemporary Colombian Art (Daros-America AG: Zurich, 2004), p. 143.

11 When asked if Salcedo would sell her working drawings, Carolyn Alexander replied: ‘Actually she doesn’t do drawings. She sketches in some notebooks, but she doesn’t do drawings. She said she’s not a drawing person, it’s just not part of her work’; interview with Carolyn Alexander, 18 October 2010.

12 Salcedo has said that she used 20 to 30 per cent of the objects she collected from the victims in her work; interview with Salcedo, 20 September 2003.

13 Salcedo reports how, despite her repeated requests, the government refused to give her any object from the building in commemoration of the events of 1985; interview with Salcedo, 18 February 2003.

14 ‘Carlos Basualdo in conversation with Doris Salcedo’, in Basualdo et al., Doris Salcedo, op. cit., p. 14.

15 Doris Salcedo, ‘Un Acto de Memoria’, D.C., no. 9 (December 2002), n.p. Translated by Tim Girven, to whom I am grateful for his kind help.

16 Doris Salcedo, ‘Un Acto de Memoria’, D.C., no. 9 (December 2002), n.p.

17 While not specifying where the event took place, Salcedo commented: ‘The only piece in that sense is that November has a date, a month and a year. Wherever there’s a complete date with a year, that means it refers to specific date…. That was the only exception, and that’s something I very much need’; interview with Salcedo, 20 September 2003.

18 This apparent exclusivity is in all probability linked to the security situation in present-day Bogotá.

19 Interview with Salcedo, 18 February 2003.

20 Adrian Searle, ‘World of Interiors’, Guardian, 12 March 2002, p. 10.

21 According to Salcedo, she had intended to use 400 chairs, but had finally to settle for 280 because of lack of finance; interview with Salcedo, 18 February 2003. The number of chairs reported in the catalogue Cantos Cuentos Colombians was 190; Herzog, ‘Conversation between Doris Salcedo and Hans-Michael Herzog’, op. cit., p. 155.

22 Susana Torre, ‘Claiming the Public Space: The Mothers of Plaza de Mayo’, in Diana Agrest, Patricia Conway and Leslie Kanes Weisman (eds.), The Sex of Architecture (Harry N. Abrams: New York, 1996), pp. 241–50.

23 Walter Baenjamin, ‘Paris, Capital of the Nineteenth Century’, in Peter Demetz (ed.) &and Edmund Jephcott (trans.), Reflections: Essays, Aphorisms, Autobiographical Writings (Schocken Books: New York, 1978), p. 155.

24 ‘Therefore Jephthah gathered all the males from Gilead, and warred against Ephraim, and the Gileadites defeated Ephraim … and occupied the margins of the Jordan, through where Ephraim’s people would have to pass on their return. And as some of them arrived there and prayed to be let through, they asked him, Aren’t you from Ephraim? And as he answered, No, I am not, they replied: Then, say “Shibboleth”, as they were unable to pronounce the same letters … and were beheaded … so that forty thousand men from Ephraim died in that war’, Judges 12: 4–6.

25 Given the inevitable sexual overtones of the word ‘crack’, it is interesting to speculate whether the work of a male artist would have attracted the same nickname in popular usage.

26 Manuel Toledo, ‘Doris Salcedo contra el racismo’, BBC Mundo, 9 October 2007.

27 Doris Salcedo, ‘Proposal for a project for the Turbine Hall, Tate Modern, London, 2007’, in Achim Borchardt-Hume, Paul Gilroy et al., Doris Salcedo: Shibboleth (Tate: London, 2007), p. 65.

28 Ibid.

29 Rachel Campbell-Johnston, ‘The Jagged Edge of Art’, The Times, 9 October 2007, p. 33.

30 ‘Latest Tate modern installation is a yawning chasm’, Epoch Times, 10–16 October 2007, p. 11.

31 The Turbine Hall was sealed off for six weeks when the construction of Shibboleth was carried out. This was not the case, for example, with Olafur Eliasson’s The Weather Project in 2003.

32 Ossian Ward, ‘Into the Breach’, Time Out London supplement, ‘Going to Tate Modern’, October 2007, p. 5.

33 A search, for example, of the ArtBibliographieModern database in early 2003 revealed 156 entries for Whiteread but only 24 for Salcedo.

34 Salcedo mentions in her interview with Hans-Michael Herzog that she did not give the local press any advanced notice of the performance; see Herzog, ‘Conversation between Doris Salcedo and Hans-Michael Herzog’, op. cit., p. 158.

35 The exhibition at White Cube took place between 15 September and 20 October 2007, while the Tate commission opened on 9 October.

36 Interview with the author, 05 December 2007.

37 Salcedo did, however, declare: ‘Originally I planned to do many more pieces. I had planned to make a group of cement furniture after finishing one piece and before beginning another, but it demanded too much energy, and I felt I had already achieved what I was looking for’; see Herzog, ‘Conversation between Doris Salcedo and Hans-Michael Herzog’, op. cit., p. 152.

38 Interview with the author, 05 December 2007. Salcedo also produced two more new pieces in 2008 for her New York gallery, Alexander and Bonin.

39 See Chin-tao Wu, Privatising Culture: Corporate Art Intervention Since the 1980s (Verso: London, 2002).

40 The Unilever Series, inaugurated in 2000, was a sponsorship deal between Unilever and Tate Modern worth £1.25 million for commissioning works in the Turbine Hall over five years. It was renewed in 2005 for a further three years for £1 million (Salcedo’s commission falls under this tranche), and again in 2008, this time to the tune of £2.1 million for the next five years; see the Tate’s press releases, ‘Unilever to pour £1.25m into Tate Gallery’, 13 May 1999; ‘Doris Salcedo to undertake the next commission in The Unilever Series’, 6 April 2007; and ‘Unilever extend sponsorship of The Unilever Series for a further five years’, 18 July 2007.

41 Interview with Achim Borchardt-Hume, 30 November 2010.

42 Email correspondence with Ruth Findlay, Senior Press Officer at Tate, 11 February 2011.

43 Salcedo stated in an interview: ‘There are around 100 people working in teams’; see Ossian Ward, ‘Into the Breach’, Time Out London supplement, p. 5.

44 Salcedo’s large furniture pieces are in any case mostly in public, not private, collections. What is more, as the commission already had a commercial sponsor in Unilever, and the title of the Unilever Series, any additional donor would inevitably have had to remain more or less anonymous. In some press reports, Shibboleth was described as ‘a new £300,000 work of art’; see Nigel Reynolds, ‘Tate Modern reveals giant crack in civilization’, Daily Telegraph, 8 October 2007. Informed sources, however, do not endorse this figure. According to the popular press, shipping the work from Colombia to London cost £23,410, and a £3,000 commission fee was paid to the artist; see ‘Revealed: How the Tate Modern’s “crack in the ground” cost the taxpayers £23,000’, Daily Mail, 24 February 2008. It is far from clear how reliable this information may actually be.