ELAINE SISMAN

Open any textbook in music history or music appreciation and the problem of Beethoven’s relation to music historiography becomes immediately apparent: is he Classical or Romantic or both or neither? Is he part of the Canonical Three of the Viennese Classical Style – Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven – or is he a chapter unto himself, as the One destined to inherit and transform, even liberate, the achievements of the Classical Duo? As Charles Rosen astutely pointed out, “it would appear as if our modern conception of the great triumvirate had been planned in advance by history”: Count Waldstein’s entry in Beethoven’s album, written in 1792 as the young composer left Bonn for Vienna, famously assured him that “You will receive the spirit of Mozart from the hands of Haydn.” 1 This attractive phrase refers to the sense of lineage both conceptual and practical that places Beethoven in a musical culture already fully fledged in its genres and expressive possibilities. Mozart’s premature death and the position of Haydn as Beethoven’s teacher in Vienna left Beethoven perfectly placed to come into his inheritance. This chapter will examine some of the dominant elements in European music in the last few decades of the eighteenth century, and explore some of his methods of appropriating and personalizing the expressive language of Haydn and Mozart. 2

By 1790, observers of the musical scene could classify the genres and structures of music according to shared assumptions about their place in musical life and the level of sophistication of their audience. A bout Vienna we read of a broad division of the musical public into the more and less knowledgeable: audience members, including patrons, comprised “connoisseurs” and “amateurs,” while performers might be classed as “virtuosi” or “dilettanti” according to their skill. 3 Music was performed in a range of venues from the grand and costly public theaters associated with courts (for example, Vienna’s Burgtheater) to the salons of the aristocracy and wealthier middle classes, from open-air gardens and coffee-houses to private homes. The composer-about-town needed to assess the intended audience for concerts or publications. C. P. E. Bach published collection after collection of piano pieces for “Kenner und Liebhaber” ; Mozart’s often-cited letter to his father at the end of 1782 about the piano concertos he was about to publish included the significant clause, “here and there connoisseurs alone can derive satisfaction; the non-connoisseurs cannot fail to be pleased, though without knowing why.” 4

Understanding the audience as a two-tiered target for composers enables us to confront the other sets of “oppositions,” some of them actually rather fluid, that informed musical life toward the end of the eighteenth century. The distinction between the public and private realms of music-making meant that some genres were always associated with larger public, festive venues – symphonies and operas, for example – while others, including most of what we now know as “chamber music,” were inveterately private – piano sonatas, trios, and songs. (Even Beethoven’s piano sonatas were not performed in public during his lifetime, with but a single exception. 5 ) Still others straddled both, depending on the city: string quartets, for example, were performed at Haydn’s grand London concerts in the 1790s but served as more private fare in Vienna. 6 The distinction may be further complicated by considering that pieces like variations for piano, published with an eye to the expanding market for home music-making, may have originated in improvisations by virtuosos at public concerts (e.g. Mozart during his benefit concert at the Burgtheater in March 1783) or at aristocratic salons (e.g. Beethoven throughout the 1790s in Vienna).

Critical writings and books on musical style toward the end of the century seemed to recognize a fundamental difference in approach between the vigorous rhythms, thick textures, and generalized melodies of the more public style, which they referred to for convenience as a “symphony style,” and the more nuanced, delicately individualized, and expressive gestures of the private realm exemplified by the “sonata style,” a distinction that sometimes transcended genre when symphonic gestures appeared in works for keyboard. Other oppositions can similarly be shown to be related to qualities of style between and within genres, such as difficult vs. accessible, galant vs. learned, elevated vs. plain, serious vs. popular, and tragic vs. comic. These ideas lead to the rich field of rhetoric, which guided speakers and writers – and, in the eighteenth century, composers and artists as well – toward choosing a stylistic “level” commensurate with occasion and audience, finding “topics,” that is, subjects and arguments, and enhancing persuasive power of the whole with appropriate figures. 7

Mozart, whose works were often found to be too difficult or “highly spiced” by his contemporaries, offered a negative view of the world of opposition he was forced to inhabit. In the same letter of 1782 cited above, he remarked that “the mean [or middle ground], truth in all things, is known and valued no longer; to receive approval one has to write something so easy to understand that a coachman can sing it right off, or so incomprehensible that it pleases precisely because no rational person can understand it.” In several works, such as the finales of the “Jupiter” Symphony (no. 41 in C K. 551) and G major String Quartet K. 387, and the overture and Armed Men scene of Die Zauberflöte , he almost revels in the disparity between the accessible galant style of simple textures and clearly phrased melodies and the difficult learned style of fugues and intricate counterpoint. Haydn, too, was a master of works that both juxtaposed and united opposites: the finale of his Symphony no. 101 (“Clock”) is on one level a typical combination of rondo with sonata form, but when its main theme returns the first time it is decorated with melodic variations, and then at its second reappearance is transformed into a fugue.

What would a young composer make of the generic and individual musical styles current in the late eighteenth century? Would he instinctively grasp the nature of such “oppositional” thinking and seek to participate in it? What would an audience member, whether connoisseur or amateur, expect of the various kinds of music he or she would hear performed during the same period? Were the rhetorical modes of stylistic “levels” and musical “topics” consciously understood by listeners? Was musical form intelligible? How was musical meaning conveyed?

Let us consider first the “idea” of the multimovement work. Rooted in almost biological necessity when interest was to be sustained over a lengthy timespan, variety in tempo allowed instrumental genres to develop a kind of “plot” based on the association of “character” with particular tempos, meters, and keys. An Andante in 6/8 was an altogether different affair from an Andante in 4/4; Andante itself had a different character from Adagio; G minor was altogether different from E![]() major as the choice of slow-movement key in a piece in B

major as the choice of slow-movement key in a piece in B![]() major; a piece with a minuet had a different effect from one without. The development of symphonies into the genre with the least “allowable” variation in external form – four movements in fast (sonata form, perhaps with slow introduction)–slow–minuet/trio–fast order – was offset by the much more flexible “private” genres for keyboard – sonatas and trios in two or three movements in virtually any order of tempi, without the necessity of sonata form up front, and with the possibility that movements may run into one another

with a half-cadence and attacca

. Neal Zaslaw describes the characters embodied in Mozart’s symphonies from the 1760s and 1770s as follows:

major; a piece with a minuet had a different effect from one without. The development of symphonies into the genre with the least “allowable” variation in external form – four movements in fast (sonata form, perhaps with slow introduction)–slow–minuet/trio–fast order – was offset by the much more flexible “private” genres for keyboard – sonatas and trios in two or three movements in virtually any order of tempi, without the necessity of sonata form up front, and with the possibility that movements may run into one another

with a half-cadence and attacca

. Neal Zaslaw describes the characters embodied in Mozart’s symphonies from the 1760s and 1770s as follows:

The first movements represent the heroic, frequently with martial character; many early- and mid-eighteenth-century sinfonia movements were limited to this character, but later ones (all of Mozart’s included) contain contrasting lyrical ideas. Appropriately, given the origins of the sinfonia in the opera pit, the two sorts of ideas – lyrical and martial – may be seen as comparable to the persistent themes of opera seria itself: love vs. honour. The andantes deal with the pastoral ... The minuets stand for the courtly side of eighteenth-century life ... The trios, on the other hand, often deal with the antic, thus standing in relation to the minuet as the anti-masque to the masque ... The finales are generally based on rustic or popular dances: gavottes, contredanses , jigs, or quick-steps. Taken together, the heroic, the amorous, the pastoral, the courtly, the antic, and the rustic or popular, represent the themes found most often in eighteenth-century prose, poetry, plays, and paintings. Only the religious is not regularly treated ... Hence, the symphony may be considered a stylized conspectus of the eighteenth century’s favourite subject-matter. 8

This list is a good first step toward assessing the psychological profile, as it were, of a multimovement work in general, but it needs broadening to include other character types that appear in Haydn’s and also Mozart’s symphonies of that era and of the 1780s and 90s, as well as music (and the other arts, especially literature) to which the terms “sensibility” and “irony” apply. Its usefulness to genres other than the symphony also needs to be assessed. Symphonic opening movements, for example, may go beyond the martial and lyrical to reflect passionate, agitato styles sometimes referred to as “Sturm und Drang.” Some of their opening gestures, without being literally martial, put one in mind of the grand style of rhetoric for which “the symphony is most excellently suited” with its “expression of grandeur, passion, and the sublime.”

9

Dance-like topics may even appear in a first movement, especially those in “danceable” meters like 3/4: the opening of Haydn’s Symphony no. 82 (“Bear,” 1785) moves rapidly from grand style to stylized minuet gesture before a lengthy fanfare leads to a half cadence. The Allegro of Mozart’s Symphony no. 38 (“Prague,” K. 504, 1786) covers so many topics after the grand style of its slow introduction that its topical variety is virtually a topic in its own right, in stark contrast to the “controlling” topics of its pastoral Andante and buffa Presto.

10

About the opening movements of quartets, sonatas, and trios, one can say only that grand style is sometimes in evidence – think only of Haydn’s “big” E![]() major Sonata Hob. X VI:52 – but that it is often amalgamated with the more intimate gestures and expressive nuances befitting the “sonata” style.

major Sonata Hob. X VI:52 – but that it is often amalgamated with the more intimate gestures and expressive nuances befitting the “sonata” style.

That slow movements offer a “respite” in some sense from the length and complexity of the first is suggested by the term “pastoral,” but the pastoral as a musical topic is generally more specific than “mere” respite: it applies to those movements that employ some combination of the compound meter, a melody with dotted rhythms (especially the dotted rhythms of the siciliana) or trochees in thirds and sixths, and prominent passages of drone bass. Just as a pastoral literary topos could include real-world pain in contrast to idyllic bliss, there may be substantial disruption in the musical pastoral. 11 Two problematic issues immediately arise. First, what is one to make of slow movements that do not exhibit any of the time-honored pastoral techniques? The slow movement of Haydn’s Symphony no. 88 in G (1787), with an idyllic first theme and passages of almost “pure” disruption without thematic content, is a Largo in 3/4 without any “overt” pastoral features but certainly reflects a pastoral “spirit” if not its literal topos. And second, what of movements that exhibit these traits but are not in slow-movement position? The first movement of Haydn’s Sonata in G Hob. XVI:40 (1784), for example, is an Allegretto in 6/8 whose first theme is certainly a pastoral “type” ; the second-movement Minuet of the Sonata in B minor Hob. X VI:32 (1776) is entirely an idyll in contrast to the stress-laden perpetuum mobile of the Trio, and in fact stands in for a slow movement in middle position. Thus, we cannot pigeonhole topic and character too narrowly.

As for minuets being “courtly” and trios “antic,” these very broad categories cannot do justice to the range of expression in Haydn’s minuets and trios, although to be sure there is a greater variety in string quartets than in symphonies. Cal ling them scherzos, marking them Allegro, filling them with hemiolas, pregnant silences, and skewed phrase structures (e.g. op. 33 no. 5, op. 77 no. 2), Haydn did much to liberate his minuets form their courtly origin. Yet he must have felt beleaguered by the evident necessity of including minuets in everything, for he told his biographer Griesinger some time during the last decade of his life, “I wish someone would write a really new minuet.” 12 Although Haydn did not mention them, Beethoven’s scherzos are usually considered to be the consummation of Haydn’s wish. One wishes for a specific date for that remark; otherwise, it seems that Haydn was either unaware of the Eroica and the op. 59 string quartets or else thought Beethoven’s piano-sonata scherzos of the 1790s not quite the innovation he had hoped for.

It is in the finales that some of the greatest stylistic oppositions met and mingled, the racy comedy of rapid-fire dance tunes brought up short by learned counterpoint (Mozart’s F major Piano Concerto K. 459; the movements in the quartet K. 387 and Haydn’s Symphony no. 101 mentioned above) or the stormy minor-key mood suddenly transformed by an

incongruously lighthearted tune (Haydn’s quartet op. 76 no. 1). The extra weight afforded to many first movements by slow introductions made the finale sound more disposable, but this balance often changed, as in those pieces with a slow introduction to their finales (Mozart’s G minor String Quintet K. 516) or finales with an exceptional density of polyphony (“Jupiter” Symphony). While it is a commonplace to find in Beethoven the first seriously “teleological” approach – that is, finale-weighted and end-driven – to the multimovement cycle, with the “Jupiter” as the Great Precursor, the long history of rhetorically mixed finales proves fruitful for Beethoven as well, in such pieces as the String Quartets in B![]() op. 18 no. 6 and in C op. 59 no. 3.

op. 18 no. 6 and in C op. 59 no. 3.

Thus, genre-types and movement-types were complex, multifarious, and sophisticated entities at the end of the eighteenth century, offering an extraordinary range of expressive and formal possibilities. Moreover, the traditional meanings of such time-honored topoi as “pastoral” and “learned” were increasingly stretched and recontextualized. “P astoral” went, in effect, from being a melodic type with a sweetly abstract sense of respite (however internally opposed) to a subject for an entire piece: the D major Sonata op. 28, with its full array of the associated techniques already in the first movement, was quickly nicknamed “Pastorale” (though not by Beethoven) and it is the title of Beethoven’s most famous “characteristic” symphony, even if its composer sought to distinguish the “expression of feelings” from “[mere] tone-painting.” 13 New topics were also developed: in Haydn’s Quartet in D op. 76 no. 5 (1797), and Beethoven’s piano sonata in D op. 10 no. 3 (1797–98), the slow movements are marked both Largo (the most “serious” slow-movement tempo) and “mesto” (“melancholy”). Haydn’s is serene (it is also marked “cantabile”), resigned, poignant, and in the unusual key of F: major; Beethoven’s is dark, and filled with “pathetic accents,” as in the series of ascending diminished seventh chords, mm. 23–25 and 62–65. 14 With such a broad field to play in, how would a composer choose his path?

Although Waldstein’s comment linking Beethoven with Mozart and Haydn has already been deconstructed by Tia DeNora – she explores the extent to which the “‘Haydn’s hands’ narrative” created a self-fulfilling prophecy in which both pupil and teacher colluded each to enhance his own reputation – it is worth considering for a moment the entire passage in relation to the musico-cultural situation in Germany and Austria.

Dear Beethoven. You are going to Vienna in fulfillment of your long-frustrated wishes. The Genius of Mozart is still mourning and weeping the death of her pupil. She found a refuge but no occupation with the inexhaustible Haydn; through him she wishes to form a union with another. With the help of assiduous labor you shall receive the spirit of Mozart from Haydn’s hands . Your true friend, Waldstein. 15

Usually interpreted as slighting if not actually insulting Haydn, and thus as a way to ensure Beethoven’s reputation as Mozart’s heir but Haydn’s superior, this flight of eloquence ought instead to be understood as emblematic of generational identification. Count Waldstein was born in 1762, six years Mozart’s junior and eight and a half years Beethoven’s senior. He saw Haydn, already sixty, as simply not in need of “Mozart’s genius” because he had his own. He was already the patriarch of the musical world: as productive as he could possibly be and too old to complete Mozart’s work for him. Someone was needed to carry on in the future.

Significant also is the use of the term genius as Muse, in an era when “genius” increasingly referred to the whole person rather than to a talent or spiritual quality of the person. 16 DeNora emphasizes that in the “first extant telling of the Haydn–Beethoven story offered by a Viennese observer to Viennese recipients” in 1796, Schönfeld’s Yearbook of Music in Vienna and Prague describes Beethoven as “a musical genius.” 17 She stresses that Schönfeld devotes more than four times as much space to Beethoven as to any other musician but Haydn, who is first. But this is simply incorrect: Schönfeld gives sixty-six lines to Haydn, who is described as a “great genius” and twenty-four lines to Beethoven, but sixty-one to Kozeluch (demonstrably no genius), more than twenty-four to various nonentities also described as “geniuses,” and twenty to Hummel, “a pleasant youth of fifteen” who is “a born genius.” 18 What is in fact significant, however, is the strongly worded statement in the Beethoven entry that “Much can be expected when such a genius entrusts himself to the most excellent master.”

Lineage and tutelage went hand in hand, although there was a certain uncertainty in what the genius was, precisely, to learn from the master. Was one to imitate him or to follow rules that he imparted? The tension between imitation and genius had long been recognized in the eighteenth century. As Edward Young wrote in 1759,

An Original ... rises spontaneously from the vital root of Genius; it grows , it is not made : Imitations are often a sort of manufacture wrought up by those Mechanics , Art , and Labour , out of preexistent materials not their own ... Learning is borrowed knowledge; Genius is knowledge innate. 19

Young’s book became wildly popular in Germany, where it appeared in two translations within a year of its original publication. Continuing on this path was Lessing, who in 1769 declared “O you manufacturers of rules, how little do you understand art, and how little do you possess of genius which creates the ideal ...” 20 Haydn virtually announced himself the enemy of rules: “Art is free and will be limited by no artisan’s fetters.” 21 He even allowed that rules of strict counterpoint could be broken, and yet he was to teach Beethoven counterpoint. Surely he did not expect Beethoven to imitate him. Indeed, some aspects of Haydn’s evidently imitable style created a fraught situation, as the article “Modest Questions put to modern Composers and Virtuosi” made clear in the inaugural volume of the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung in 1798: the author, probably Zelter, decried the current fashion for slavishly imitating every innovation of Haydn until “we are used to them, they make no more effect ... these things have been spoiled by the imitators.” 22 This may perhaps have affected Haydn’s sensitivity about his pupils publicly identifying themselves as such; he always referred to Pleyel as his pupil when the latter was his rival in London, and he wanted Beethoven to identify himself as “pupil of Haydn” on the title page of his first “official” publication, the op. 1 piano trios. Beethoven, for his part, jealously guarded his innovations from imitators, writing to Eleonore von Breuning in 1794 of the necessity to publish his piano variations before imitators made off with his trademarks. 23

Several recent studies deal with specific aspects of Beethoven’s modeling procedures, in which he based some of his pieces on works by Haydn and Mozart, choosing the ordering of movements, their keys and formal types, and details of texture, harmonic planning, and even melodic contour, as templates. 24 These studies join a considerable number of earlier essays in which Beethoven’s relationship to tradition has been extensively explored. 25 Beethoven’s debts to Haydn are more often considered to involve particular structures, processes, and strategies, rather than entire works as models. But the reader will find one essay declaring a piece to be based clearly on Mozartean procedures, while another will assert the same piece to be based on Haydn. 26 How does one tell? What are the general and specific features of style upon which Beethoven drew? And are the pieces by Beethoven that reveal “modeling” necessarily early? Beethoven copied out works by older masters throughout his life, from J.S. Bach and Handel to C. P.E. Bach to Haydn and Mozart, whenever he needed them. 27

Beethoven’s reasons for making a score copy in 1794 of Haydn’s Quartet in E![]() major op. 20 no. 1 (1772) have not been ascertained, since he wrote no quartets at that time and his first essay in string-trio writing, op.

3 (written in 1794), was modeled at least in its outward plan of six movements (Allegro con brio–Andante–Menuetto–Adagio–Menuetto– Finale) on Mozart’s Divertimento K. 563 (with the Adagio in A

major op. 20 no. 1 (1772) have not been ascertained, since he wrote no quartets at that time and his first essay in string-trio writing, op.

3 (written in 1794), was modeled at least in its outward plan of six movements (Allegro con brio–Andante–Menuetto–Adagio–Menuetto– Finale) on Mozart’s Divertimento K. 563 (with the Adagio in A![]() major and Andante in B

major and Andante in B![]() major reversed).

28

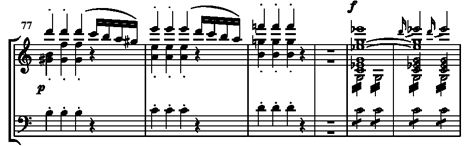

The finale in both is a very relaxed sonata-rondo. Yet a comparison of the finales of Beethoven’s trio with Haydn’s quartet suggests that Haydn’s movement was the source for thematic and harmonic details despite the strikingly smaller dimensions of the latter (160 measures compared to Beethoven’s 457!). Not only are the opening themes similar in contour, but Beethoven makes more explicit Haydn’s off-tonic opening (Example 4.1

). Haydn compresses considerable harmonic activity into the passage of syncopation emerging from the theme (mm.11–32), while Beethoven turns his into a big three-part sequence (I–vi–V, mm. 25–53), with figuration moving from violin to viola to cello. Both second themes ascend from f1

to c3

as a goal, then make their way back down. Beethoven’ s lengthy closing section returns to the three-fold presentation of his bridge, reversing the order of instruments and opting for repetition rather than sequence. Each exposition descends to B

major reversed).

28

The finale in both is a very relaxed sonata-rondo. Yet a comparison of the finales of Beethoven’s trio with Haydn’s quartet suggests that Haydn’s movement was the source for thematic and harmonic details despite the strikingly smaller dimensions of the latter (160 measures compared to Beethoven’s 457!). Not only are the opening themes similar in contour, but Beethoven makes more explicit Haydn’s off-tonic opening (Example 4.1

). Haydn compresses considerable harmonic activity into the passage of syncopation emerging from the theme (mm.11–32), while Beethoven turns his into a big three-part sequence (I–vi–V, mm. 25–53), with figuration moving from violin to viola to cello. Both second themes ascend from f1

to c3

as a goal, then make their way back down. Beethoven’ s lengthy closing section returns to the three-fold presentation of his bridge, reversing the order of instruments and opting for repetition rather than sequence. Each exposition descends to B![]() 2, slurring it over the barline to B:, a mini-retransition to a partial return of the main theme, a sonata-rondo inflection. The harmonic goal of each development section is C minor, which Beethoven reaches immediately because of the looseness of the sonata-rondo format. Haydn moves first to F minor and sequences the main theme in a polyphonic passage more metrically sophisticated than anything in Beethoven’s square-cut finale. From C minor each continues with a harmonically dense passage moving successively from a dominant or diminished seventh to its tonic in related keys. Haydn moves to a full retransition

on a dominant pedal, and a reiteration of the B

2, slurring it over the barline to B:, a mini-retransition to a partial return of the main theme, a sonata-rondo inflection. The harmonic goal of each development section is C minor, which Beethoven reaches immediately because of the looseness of the sonata-rondo format. Haydn moves first to F minor and sequences the main theme in a polyphonic passage more metrically sophisticated than anything in Beethoven’s square-cut finale. From C minor each continues with a harmonically dense passage moving successively from a dominant or diminished seventh to its tonic in related keys. Haydn moves to a full retransition

on a dominant pedal, and a reiteration of the B![]() –B

–B![]() fillip. In Beethoven’s final statement of the theme, he expands that little transition to four full measures.

fillip. In Beethoven’s final statement of the theme, he expands that little transition to four full measures.

Example

4.1

(a) Haydn, String Quartet in E![]() op. 20 no. 1, finale, mm. 1–5

op. 20 no. 1, finale, mm. 1–5

Presto

(b) Beethoven, String Trio in E![]() op. 3 , finale, mm. 1–7

op. 3 , finale, mm. 1–7

Allegro

Beethoven’s later appropriations contained more conscious and inevitable attempts at distancing. For example the first movement of his First Symphony (op. 21, 1800) relates to the first (and to a much lesser extent the last) movements of the last symphony by Mozart (K.551, the “Jupiter,” 1788) and the last C major symphony by Haydn (no. 97, 1791). 29 Here we see, I believe, a clear example of Beethoven choosing models for his symphonic debut with the purpose of homage, of placing himself within a tradition, laced with one-upmanship, and casting the result in the most brilliantly conventional and instantly recognizable of eighteenth-century symphonic modes: the “C major symphony” tradition with its trumpets and drums and “ceremonial flourishes.” 30 (I will refer to these pieces as the First, the 97th, and the “Jupiter,” and trust that their composers can be ascertained therefrom.) This canny choice of a festive mode to please the public drives the striking similarities among the three grand-style opening Allegro themes: each is based on an “annunciatory” ascending fourth with a dotted rhythm, the “Jupiter’s” filled in, the 97th’s hollow, the First’s nearly hollow but inflected by the leading tone (Example 4.2 ). Beethoven’s conflates the unison opening/harmonized sequel phrase structure of the “Jupiter” with another C major theme structure, that of a piano opening phrase restated on the supertonic, as in Haydn’s String Quartet op. 33 no. 3 (1781). 31 He does this with a quiet opening in the strings switching to wind chords which antiphonally cue the next statement, first toward the supertonic, then toward the dominant. The expansion of the antiphonal winds passage in the recapitulation into complete chromatic ascent comes from the dissonant chromatic recasting of the opening theme in the “Jupiter” finale; the wind transition into both development and recapitulation comes from the “Jupiter” first movement.

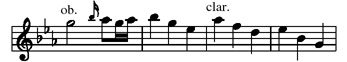

Example 4.2 Three first-movement themes

(a) Mozart, “Jupiter” Symphony, mm. 1–8

Allegro vivace

(b) Haydn, Symphony no. 97, mm. 1–11

Vivace

(c) Beethoven, Symphony no. 1, mm. 1–8

Allegro con brio

Only one other significant element is triggered by the “Jupiter,” I believe, beyond the harmonic plan of the development section, convincingly demonstrated by Carl Schachter: 32 the minor episode which interrupts what appears to be a closing tutti after the second theme (mm. 77–87). Mozart signifies the end of the second theme and beginning of the closing group with a “doubting” passage whose questioning chords trickle out in a five-beat grand pause, then a “minor shock,” a sudden tutti C minor chord. 33 The rhetorical effect of this sequence of events is a powerful emotional charge, delivered by first breaking off and then virtually collaring the listener with a forceful direct address (Example 4.3a ). Moreover, in the finale of the “Jupiter,” a C minor “swerve” sets up a preview of the conventional “Mannheim” cadence before the final close (Example 4.3b ). Beethoven’s turn to minor provides virtually the opposite effect: from a cheerful wind-dominated second theme to a conventional vigorous tutti, we suddenly enter a mysterious shadow world in the low strings (mm.77ff.), the ombra topic of supernatural operatic scenes (Example 4.3c ). Wind intervention and the conventional “Mannheim” cadence (mm.85–88, found also in the “Jupiter” finale, mm. 145–51) are needed before the “true” closing theme can begin. Functioning as an antipode to the “C-major symphony style,” the ombra is an expressive device of some sophistication.

Example 4.3

(a) Mozart, “Jupiter” Symphony, mvt.1, minor “shock,” mm.77–82

(b) “Jupiter’ Symphony, mvt.4, minor “swerve,” mm.125–29

(c) Beethoven, Symphony no. 1, mvt.1, ombra episode beginning m.77

(d) episode ending with “Mannheim” cadence, mm.85–88

![]()

But it is from the 97th that Beethoven derives the most striking effects of his first movement: the off-tonic opening of the slow introduction, the use of a chord progression in the introduction that returns later in the movement, and the idea of a slow introduction propelling itself into the Allegro without a cadential chord and fermata. Haydn’s 97th is the only one of his slow introductions to use the beginning of the Allegro as the resolution of its final chord progression. That this chord progression has also been heard at the beginning of the introduction is especially significant because it means that the potentially static idea of “symmetry” is used as an agent of propulsion; moreover, this progression, which begins with a diminished seventh chord (the vii7 of V), appears in the closing groups of both exposition and recapitulation (Example 4.4a ). Beethoven simply lops off the opening unison-tonic measure of 97 in order to begin, notoriously, on the dominant of the subdominant. The passage does not provide a root-position tonic chord until m.8, the appearance of which triggers a six-measure cadential chord progression propelling itself into the Allegro (Example 4.4b ). Beethoven then saves this progression until the very end of the piece, bringing it back over and over in mm.271–77 of the coda whereupon it leads to the most brilliant fanfare sound of the entire movement.

Thus the earliest example of Beethoven’s harmonic long-range planning – a virtual signature in symphonies from the Eroica on – can be revealed as very likely inspired by Haydn. But the wholesale recurrence of slow introductions in the original tempo – the Pathétique Sonata op. 13 and La Malinconia in the finale of the quartet op. 18 no. 6 are the earliest of these – probably owe their existence to Mozart’s D major String Quintet K. 593 (1790), in which the Larghetto introduction returns during the coda, as well as the dramatic stroke whereby the opening – drumroll and all – of the “Drumroll” Symphony, no. 103, returns in the recapitulation. (The latter has a quite different effect from the “disguised” thematic incorporation of the slow introduction melody into the Allegro itself.) Thematic reminiscence of the slow introduction in its original tempo is entirely different from the recall of a harmonic progression for closural effect.

Example 4.4

(a) Haydn, Symphony no. 97, mvt. 1, mm. 2–4, chord progression in slow introduction

(b) Beethoven, Symphony no. 1, mvt. 1, mm. 8–11, chord progression in slow introduction

Mozart’s influence on Beethoven’s treatment of minor keys, especially C minor, has been noted in detail by Michael Tusa and Joseph Kerman.

34

Mozart’s C minor Piano Concerto no. 24 K. 491 is especially important in this respect; Beethoven must have known it before he heard it at the Augarten in 1799, exclaiming to the composer J. B. Cramer after the performance, “Cramer, Cramer! We shall never be able to do anything like that!”

35

Tusa points out the similarities between the first movements of K. 491 and Beethoven’s C minor Piano Trio op. 1 no. 3, beyond their triple meter and unison opening: their “main theme (triple meter, downbeat start on 1î, arpeggiated melody, melodic emphasis on î, soft dynamics) and in the specific treatment of the beginning of the recapitulation” (figuration passage over dominant pedal leading to forte recasting of the theme).

36

There is another structural similarity: the two second themes in the solo exposition of K. 491, each with its own closing figuration and trill cadence, may be the source of the large dimensions and thematic multiplicity

of Beethoven’s exposition, although the dimensions of the trio are closer to the recapitulation of the concerto. (Example 4.5

gives the principal themes of the Mozart.) Beethoven’s first theme is divided into the arresting unison gesture described by Tusa and a more motivically repetitive sequel that recurs in the bridge and at the end of the closing section. Moreover, the second theme is divided as well into a more rhythmically active and a more contemplative theme, the first in E![]() and the second in A

and the second in A![]() ; a third contemplative “interlude” appears in the closing section. When Mozart’s “first second theme” appears in the recapitulation, its reiteration by the piano is in the subdominant. (Example 4.6

shows each of the Beethoven themes.) While Beethoven’s works for piano of the 1790s are routinely called “symphonic” because of their size and especially because of their four-movement plans, the mere fact that the concerto is in three movements ought not to disqualify it as a model.

; a third contemplative “interlude” appears in the closing section. When Mozart’s “first second theme” appears in the recapitulation, its reiteration by the piano is in the subdominant. (Example 4.6

shows each of the Beethoven themes.) While Beethoven’s works for piano of the 1790s are routinely called “symphonic” because of their size and especially because of their four-movement plans, the mere fact that the concerto is in three movements ought not to disqualify it as a model.

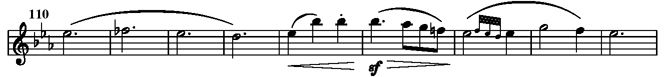

Example 4.5 Mozart, Piano Concerto no. 24 in C minor K. 491, mvt. 1

(a) main tutti theme, mm. 1–6

Allegro

(b) theme 2a, mm. 148–51

(c) theme 2b, mm. 201–04

The evocative qualities and intrinsic characteristics of the different keys, an essential part of eighteenth-century thinking, are powerfully displayed in the idea of a composer choosing his models from among pieces in the same key.

37

Thus one looks immediately to Mozart’s “Prague” Symphony in assessing the existence of a structural or expressive or textural “source” for Beethoven’s Second – and indeed it is to be found, in both the slow introduction and main theme. In cases of direct thematic quotations or allusions, however, the key of the original seems less an issue. For example, Beethoven quotes the famously beautiful G major melody of the slow movement of Haydn’s Symphony no. 88 in the Allegretto ma non troppo movement of his Piano Trio in E![]() op. 70 no. 2, in A

op. 70 no. 2, in A![]() major.

38

But Beethoven certainly didn’t come to terms with his forebears only through quotation

and modeling, on the one hand, or through assessment and expansion of contemporary expectations of topics and structures of the principal genres, on the other. He also transformed the decorum of conventional or characteristic formal designs in ways that asserted “difficulty” as an aesthetic principle.

39

major.

38

But Beethoven certainly didn’t come to terms with his forebears only through quotation

and modeling, on the one hand, or through assessment and expansion of contemporary expectations of topics and structures of the principal genres, on the other. He also transformed the decorum of conventional or characteristic formal designs in ways that asserted “difficulty” as an aesthetic principle.

39

Example 4.6 Beethoven, Piano Trio in C minor op. 1 no. 3, mvt. 1 (a) theme 1a, mm. 1–7

Allegro con brio

(b) theme 1b, mm. 10–14

(c) theme 2a, mm. 59–63

(d) theme 2b, mm. 76–79

(e) theme 3 (within closing), mm. 110–18

A single example can suffice to reveal Beethoven’s transformation of decorum in a type of piece utterly familiar to his contemporaries: the variation form as a movement in a larger work. 40 The rhetorical concept of decorum, or propriety, is clearly outlined by Cicero, in Orator . The orator must consider “what to say, in what order, and in what manner and style to say it.” As for the latter,

In an oration, as in life, nothing is harder than to determine what is appropriate. The Greeks called it prépon; let us call it decorum or “propriety” ... This depends on the subject under discussion, and on the character of both the speaker and the audience ...Moreover, in all cases the question must be “How far?” For although the limits of propriety differ for each subject, yet in general too much is more offensive than too little ... 41

In works by Haydn and Mozart, the decorum of a variation movement – its traditional and hence normative technical and expressive limits – depended upon its position in the work, upon genre, and upon the nature of the theme. In general, its implicit code included several different proprieties: a “propriety of ordering,” in which simpler textures appeared early in a set while imitative polyphony never did, a “propriety of performance style,” in which extremes of instrumentation and dynamics would be introduced for local contrasts, rarely as the topic of an entire variation, and “propriety of contrast and return,” in which distantly related or contrasting material would be followed by returns of the theme melody. Finally, the theme itself would observe a certain propriety, not only in its two-reprise (binary) structure with clearly delineated phrases, but also in the degree of repetition and contrast in its melodic segments, rhythms, and textures. 42

All of these proprieties devolve upon the concept of familiarity and recognition – without which, Koch said, “[the variations] give the impression of a group of arbitrarily related pieces which have nothing in common with each other, and for whose existence and ordering one can imagine no basis.” 43 Michaelis’s evocative account of variation form, in an article of 1803 on repetition and variation, asserts that

if the basic theme, the main melody, appears clothed in a new manner, under a delicate transparent cloak, so to speak, then the soul of the listener obtains pleasure, in that it can automatically look through the veil, finding the known in the unknown, and can see it develop without effort. Variation demonstrates freedom of fantasy in treatment of the subject, excites pleasant astonishment in recognizing again in new forms the beauty, charm, or sublimity already known, attractively fusing the new with the old without creating a fantastic mixture of heterogeneous figures ... Variation arouses admiration insofar as everything latent in the theme is gradually made manifest, and unfolds [into] the most attractive diversity. 44

Michaelis stresses that the process of unfolding the secrets of the theme happens “gradually.”

By the time Beethoven began work in 1799 on the fifth of his op. 18 string quartets, he had already written at least twenty sets of variations, including six movements in larger works, although none in as “serious” a genre as the quartet. I believe that this movement radically breaks with the decorum

of classical variation movements, and that this is clearest in precisely those areas in which Beethoven appropriates earlier techniques. First, the “abstract construction” of the theme (Kerman’s disparaging term)

45

has a level of repetitiveness unusual in that it involves pitches as well as rhythms (Example 4.7a

); it thus differs from the repetitive rhythmic patterns underlying the themes of Haydn’s String Quartet op. 76 no. 6 (first movement) and Symphony no. 75 (second movement), as well as Mozart’s B![]() major Piano Concerto K. 450 (second movement). The first variation recasts the ordering of classical variations. Normally, a contrapuntal or fugal variation would be placed at or near the end of a set: here the cello alone immediately sets out the terms of a gritty contrapuntal buildup, with a crescendo to underscore the registral expansion and offbeat sforzandos to deny a final coming together of the disparate voices and registers (Example 4.7b

). By virtue of its prominent position, this variation becomes a manifesto, asserting control over the language of the classical variation while challenging its decorum.

major Piano Concerto K. 450 (second movement). The first variation recasts the ordering of classical variations. Normally, a contrapuntal or fugal variation would be placed at or near the end of a set: here the cello alone immediately sets out the terms of a gritty contrapuntal buildup, with a crescendo to underscore the registral expansion and offbeat sforzandos to deny a final coming together of the disparate voices and registers (Example 4.7b

). By virtue of its prominent position, this variation becomes a manifesto, asserting control over the language of the classical variation while challenging its decorum.

Variations 2 and 3 return to standard equipment – triplet-sixteenth figuration in the first violin in the former and theme fragments accompanied by thirty-second notes in the latter. Yet the texture is again unusual: the thirty-second note pattern consists of slurred appoggiaturas instead of the customary broken-chord or scalar patterns, and the thematic fragments are themselves fragmented in instrumentation and register, ending the first period with viola and cello joined at the octave in an odd feminine cadence. The fourth variation draws on the last one of Haydn’s “Emperor” Quartet variations, op. 76 no. 3, reharmonizing the theme, but accomplishes this here by altering the melody itself in a strange borrowing of the melodic minor scale in B minor to end the first period in the mediant. It hardly prepares for the fifth and last variation, in which the high trill, offbeat accents, and jumping cello line both balance the first variation and exceed the expressive limits of allowable contrast; indeed, Kerman refers to its unprecedented driving orchestral style (Example 4.7c ). 46

These novelties are surpassed by the coda, which begins as a deceptive cadence in ![]() VI on the same disjunct cello figuration, Beethoven’s only literal appropriation from Mozart’s K. 464. Beethoven wittily inverts the theme in sixteenth notes as contrary-motion accompaniment to its original rhythm; each statement reassigns the theme and counterpoint, beginning with a theme/counterpoint pairing of second violin/viola (B

VI on the same disjunct cello figuration, Beethoven’s only literal appropriation from Mozart’s K. 464. Beethoven wittily inverts the theme in sixteenth notes as contrary-motion accompaniment to its original rhythm; each statement reassigns the theme and counterpoint, beginning with a theme/counterpoint pairing of second violin/viola (B![]() ), then cello/first violin (D), then viola/second violin counterpoint (G) (Example 4.7d

). Moving the theme through the voices in this way seems to be a reference to Haydn’s cantus firmus technique in the quartets of op. 76 published in the same year. Contrary motion becomes the logical development

of the closing measures of the theme, while the sudden turn to B

), then cello/first violin (D), then viola/second violin counterpoint (G) (Example 4.7d

). Moving the theme through the voices in this way seems to be a reference to Haydn’s cantus firmus technique in the quartets of op. 76 published in the same year. Contrary motion becomes the logical development

of the closing measures of the theme, while the sudden turn to B![]() at the beginning of the coda may correlate enharmonically with the single biggest earlier shock in the movement, the A: in the melody of variation 4.

at the beginning of the coda may correlate enharmonically with the single biggest earlier shock in the movement, the A: in the melody of variation 4.

Example 4.7 Beethoven, String Quartet op. 18 no. 5, second mvt. (a) theme

(b) var. 1

(c) var.5

(d) coda

Beethoven breaks Classical decorum by calling into question every one of the proprieties mentioned above. His most radical step is his first, for it is here in variation 1, in the sudden eradication of harmony and conventional register in favor of the cello subject, that he defamiliarizes the theme. In a variation movement of 1799 one might diverge very widely from the theme, but a general propriety of familiarity asserted that the beginning was not the place for such a technique. By “making strange” the beginning of a variation work, Beethoven effectively violated Michaelis’s context of the intelligible environment in which the theme can be recognized. This is not to say, of course, that the listener of 1799 could not make sense of the relationship between variation and theme. But by inserting a new level of difficulty into a previously more accessible form, Beethoven was staking his claim to a new decorum. And he expanded his claim so far in subsequent years that some listeners still instinctively reject the presence of what Beethoven knew to be his inheritance.