WILLIAM KINDERMAN

The piano represented a springboard for Beethoven’s achievements and a primary vehicle for the pathbreaking innovations of his evolving musical style. His early reputation as a prodigy at Bonn rested on his playing of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier , and his success at Vienna after 1792 was founded in no small measure on his ability to improvise at the keyboard. In assessing Beethoven’s musical legacy for the piano, we should first consider the cultural context of his music and the relation of his works to his activities as a performing virtuoso. As some recent studies have emphasized, Beethoven’s career coincided with and lent support to the rise of the notion of the autonomous musical artwork – the unique composition regarded as independent of specific conditions of performance. 1 The fulfillment of Count Waldstein’s famous prophecy made at Bonn “you shall receive Mozart’s spirit from Haydn’s hands” 2 – as well as the fortification of Beethoven’s style from earlier models, such as J.S. Bach, 3 reflected the high cultural ambitions of his art as an indispensable basis for his originality. The negative tone of some early reviews of Beethoven’s works sprang from perceptions of their challenging character and their overturning of conventions – reasons why a more thorough acquaintance based on repeated hearings was appropriate. 4

In evaluating this change in aesthetic reorientation, it is tempting but misleading to oppose the improvisatory tradition of Mozart and Beethoven as orators in tones with the growing recognition of autonomous works at the threshold of the nineteenth century. 5 Important musical forms and procedures such as sonata designs, fugue, rondo and variations were established vehicles for extemporized performance. The performance context in private aristocratic salons is poorly documented, and public concerts of solo piano works hardly existed; yet the evidence available indicates that published solo works were often formalized versions of music originally presented as improvisation or fresh composition. F or instance, Mozart writes in a letter of 24 October 1777 from Mannheim to his father about improvising what became the Sonata in C major K. 309 (with a different slow movement): “I then played ... all of a sudden a magnificent sonata in C major, out of my head, with a rondo at the end – full of din and sound.” 6 Ferdinand Ries and Carl Czerny reported how Beethoven performed the “Waldstein” Sonata op. 53 in its original unpublished version from 1803–04 with the Andante favori WoO 57 as slow movement, and Czerny even explains the special title of the piece as arising out of this performance context: “Because of its popularity (for Beethoven played it frequently in society) he gave it the title ‘Andante favori.’” 7 A decade later, in 1814, after he had given up performing on account of his deafness, Beethoven still insisted vehemently on the essential unity of performance and work in comments made to Johann Wenzel Tomaschek: “It has always been known that the greatest pianoforte players were also the greatest composers; but how did they play? Not like the pianists of to-day, who prance up and down the keyboard with passages which they have practised – putsch, putsch, putsch ; – what does that mean? Nothing! When a true pianoforte virtuoso played it was always something homogeneous, an entity, if written down it would appear as a well thought-out work. That is pianoforte playing; the other thing is nothing!” 8

Beethoven’s musical thought was deeply rooted in the rhetorical art of the sonata style, whereby the notion of musical form as a process is tantamount: many theorists have regarded his piano sonatas as exemplifying an “organic” model of musical integration, in which motivic relations, harmonic and tonal factors, or melodic and voice-leading continuities can be given emphasis. 9 Such demonstrations of internal unity, however important, fail to adequately address issues of expressive character and dramatic meaning, 10 or the rich variety of musical textures. Like Mozart, Beethoven often assimilated into his keyboard works the textures of chamber music and orchestral and vocal idioms. The most specifically “pianistic” works are often those of a virtuosic cast, employing elaborate figuration, original pedal effects and a brilliant use of trills. One thinks in this regard especially of sonatas like op. 2 no. 3, op. 10 no. 3, and the “Appassionata,” “Waldstein,” and “Hammerklavier” Sonatas, as well as of the concertos and the variation sets, particularly the “Eroica” and “Diabelli” Variations.

The improvisational currents in Beethoven are thus balanced against his penchant for deterministic construction. He was a formidable musical architect, but typically filled out such structural mapping with imaginative and surprising expressive events, which strain the formal frameworks without quite breaking them. Paul Mies, in his 1970 study The Crisis of the Concerto Cadenza in Beethoven

, identified a key element in the evolution of Beethoven’s later style as the increasing incorporation of improvisatory elements into his style, culminating in works like the Quartet in C: minor op. 131.

11

The moment of enhanced stylistic internalization of the resources of extemporization came in 1809, the time when Beethoven, in response

to his increasing loss of hearing, retreated from the concert plat-form. At this point he wrote out solo cadenzas to his earlier concertos, and incorporated the cadenzas to his Concerto in E![]() major op. 73 directly into the score, thereby foreclosing the opportunity for other performers to improvise. As his deafness became virtually complete by about 1818, Beethoven invested ever more compositional labor in the form of written sketches that often record improvisatory flights of fancy. The later sketchbooks provide a revealing window onto Beethoven’s capacity to spontaneously generate new musical conceptions and rationally shape, refine, and develop these ideas. The present survey of the piano works considers both aspects, exploring issues of musical character no less than formal unity and structural integration.

major op. 73 directly into the score, thereby foreclosing the opportunity for other performers to improvise. As his deafness became virtually complete by about 1818, Beethoven invested ever more compositional labor in the form of written sketches that often record improvisatory flights of fancy. The later sketchbooks provide a revealing window onto Beethoven’s capacity to spontaneously generate new musical conceptions and rationally shape, refine, and develop these ideas. The present survey of the piano works considers both aspects, exploring issues of musical character no less than formal unity and structural integration.

For Beethoven, as for Mozart, the concerto for piano was an important dramatic genre in which the composer himself assumed the role of soloist. Between 1790 and 1809 Beethoven wrote five piano concertos, the first two of which he revised repeatedly for his own performances. The C major Concerto op. 15 was written mainly in two stages, in 1795 and 1800. The “second” concerto in B![]() major eventually published as op. 19 was actually the first of the concertos composed; in its original form dating from the early 1790s at Bonn it probably had an entirely different finale, the movement now known as the Rondo in B

major eventually published as op. 19 was actually the first of the concertos composed; in its original form dating from the early 1790s at Bonn it probably had an entirely different finale, the movement now known as the Rondo in B![]() major WoO 6. Beethoven’s perfectionistic struggle for compositional mastery and the inevitable comparison with Mozart’s great legacy of piano concertos are reflected in the prolonged genesis of the B

major WoO 6. Beethoven’s perfectionistic struggle for compositional mastery and the inevitable comparison with Mozart’s great legacy of piano concertos are reflected in the prolonged genesis of the B![]() Concerto. The rondo finale WoO 6 was modeled on the finale of Mozart’s Piano Concerto in E

Concerto. The rondo finale WoO 6 was modeled on the finale of Mozart’s Piano Concerto in E![]() K. 271, a work whose influence also left traces in Beethoven’s first movement. It was the D minor and C minor concertos of Mozart, however, together with the opening Allegro maestoso of the C major K. 503, that most deeply impressed Beethoven.

K. 271, a work whose influence also left traces in Beethoven’s first movement. It was the D minor and C minor concertos of Mozart, however, together with the opening Allegro maestoso of the C major K. 503, that most deeply impressed Beethoven.

The composer himself expressed dissatisfaction with the concerto in B![]() in his letter to Breitkopf & Härtel of 22 April 1801:

in his letter to Breitkopf & Härtel of 22 April 1801:

I wish to add that one of my first concertos and therefore not one of the best of my compositions , is to be published by Hoffmeister, and that Mollo is to publish a concerto which , indeed, was written later , but which also does not rank among the best of my works in this form . 12

Despite these reservations, the B![]() concerto is an attractive and subtle work. The opening Allegro con brio opens with a dualistic gesture: an assertion

of the tonic chord forte

, spelled out in energetic dotted rhythm, followed by lyrical legato phrases played piano

. Beethoven develops both elements as the movement unfolds, with the lyrical impulse pervading the initial entry of the solo piano and the ethereal pianissimo

passage heard in the remote key of D

concerto is an attractive and subtle work. The opening Allegro con brio opens with a dualistic gesture: an assertion

of the tonic chord forte

, spelled out in energetic dotted rhythm, followed by lyrical legato phrases played piano

. Beethoven develops both elements as the movement unfolds, with the lyrical impulse pervading the initial entry of the solo piano and the ethereal pianissimo

passage heard in the remote key of D![]() major (G

major (G![]() major in the recapitulation) near the beginning of the second subject group, whereas the more assertive passages with dotted rhythms dominate other parts of the form, including much of the solo cadenza.

major in the recapitulation) near the beginning of the second subject group, whereas the more assertive passages with dotted rhythms dominate other parts of the form, including much of the solo cadenza.

The reflective, hymn-like character of the Adagio harbors a surprising dramatic intensity, to which the pianist contributes with elaborate keyboard figuration and a compelling rhetorical expression. In their inward fervor, the soloistic passages marked “con gran espressione” near the end of the movement foreshadow the great slow movement of the Fourth Concerto. The rondo, in 6/8 time, is characterized by immense vitality and humorous wit – nowhere more than in the blustering central episode in minor keys, where Beethoven highlights the syncopated accents of the main subject. The rondo theme displays a contour similar to the opening of the first movement. In particular, it employs an initial motive descending a third to the tonic degree, paralleling the opening descending triadic gesture of the Allegro con brio, and these pitches are followed by the stepwise rising third A–C, which recalls the lyrical phrase in mm. 2–4 of the first movement. These thematic relations seem to parallel the motivic kinships between the outer movements of Mozart’s D minor concerto, as Geoffrey Block has pointed out. 13

In the C major Concerto op. 15, Beethoven retains the general formal outlines of the preceding work, with an opening Allegro con brio and a high-spirited rondo finale enclosing a thoughtful slow movement: a spacious, decorative, almost hymn-like Largo in A![]() major. In its brilliance and grandeur, the first movement is somewhat reminiscent of Mozart’s Concerto K. 503, in the same key. In the orchestral ritornello, Beethoven sets off the lyrical second subject through a series of striking modulations, to E

major. In its brilliance and grandeur, the first movement is somewhat reminiscent of Mozart’s Concerto K. 503, in the same key. In the orchestral ritornello, Beethoven sets off the lyrical second subject through a series of striking modulations, to E![]() major, F minor, and G minor – a sequence of ascending keys that also assumes importance in the development section.

14

As in the B

major, F minor, and G minor – a sequence of ascending keys that also assumes importance in the development section.

14

As in the B![]() concerto, Beethoven’s humor is most obvious in the finale, especially in the colorful subordinate theme in A minor, with its insistent accented turns and staccato bass. But perhaps the funniest idea in the entire concerto is found near the end of the longest of the three solo cadenzas for the first movement that Beethoven wrote out in 1809. He indulges here in a trick that he employed in his own solo performances. After twice sounding the trills that would normally signal the end of the cadenza and imminent re-entrance of the orchestra, Beethoven mischievously continues with the lengthy cadenza. At last, after presumably exasperating conductor, orchestra,

and audience with such delaying tactics, he interpolates another surprise – a soft, provocatively understated arpeggiated chord on the already much-emphasized dominant seventh chord, the doorstep to the cadence. This gesture prefaces the long-awaited – yet no longer predictable – return of the orchestra.

15

concerto, Beethoven’s humor is most obvious in the finale, especially in the colorful subordinate theme in A minor, with its insistent accented turns and staccato bass. But perhaps the funniest idea in the entire concerto is found near the end of the longest of the three solo cadenzas for the first movement that Beethoven wrote out in 1809. He indulges here in a trick that he employed in his own solo performances. After twice sounding the trills that would normally signal the end of the cadenza and imminent re-entrance of the orchestra, Beethoven mischievously continues with the lengthy cadenza. At last, after presumably exasperating conductor, orchestra,

and audience with such delaying tactics, he interpolates another surprise – a soft, provocatively understated arpeggiated chord on the already much-emphasized dominant seventh chord, the doorstep to the cadence. This gesture prefaces the long-awaited – yet no longer predictable – return of the orchestra.

15

Like the two earliest concertos, the Third Concerto had an extended compositional genesis. Its origins reach back to Beethoven’s journey to Berlin in 1796, when he made the notation “To the Concerto in C minor kettledrum at the cadenza” – a remark which relates to a passage near the end of the first movement of the finished work. Beethoven may have originally intended to play this concerto at his benefit concert at Vienna on 2 April 1800, but the piece seems not to have been completed in time; he probably performed a revised version of the older C major Concerto op. 15. The C minor concerto was apparently played for the first time on 5 April 1803, with the composer at the piano.

The initial phrase of the first movement is anchored by a cadential figure in dotted rhythm – the same motive which is tapped out in the timpani at the end of the solo cadenza. This motive has a militayr flavor that harks back to Mozart’s example;

16

in Beethoven’s hands it becomes a prominent compositional element throughout the Allegro con brio. The opening orchestral ritornello is quite extended and embraces statements of a contrasting lyrical subject in E ![]() major and C major before the main theme is powerfully reasserted in the minor, with an effect of pathos. The ensuing entrance of the solo piano is fortified by ascending scales leading to the principal subject boldly proclaimed in octaves. Later, in the development, Beethoven often reduces this thematic gesture to the martial cadential motive, which is exchanged between the piano, winds, and strings.

major and C major before the main theme is powerfully reasserted in the minor, with an effect of pathos. The ensuing entrance of the solo piano is fortified by ascending scales leading to the principal subject boldly proclaimed in octaves. Later, in the development, Beethoven often reduces this thematic gesture to the martial cadential motive, which is exchanged between the piano, winds, and strings.

Beethoven’s treatment of his main theme in the solo cadenza is especially original and displays a vast architectural logic. After the opening “lead-in,” he dwells at length on the interval of a rising third from its first bar, as brilliant arpeggiations carry the music into distant tonal regions. Near the conclusion of the cadenza, Beethoven resumes this thread, developing the second bar of the theme in combination with an extended double trill. What remains are the following two bars with their striking dotted rhythm. These are played by the “kettledrum at the cadenza,” with the effect heightened by the mysterious harmonic context and by the delay of the tonic resolution. Strictly considered, the cadenza embraces not only the solo but also the timpani statements, and ends only with the long-postponed C minor cadence, where a new dialogue between the piano and strings leads to the terse close of the movement.

The slow movement is a reflective Largo, whose expressive contrast to the

pathos of the outer movements is heightened by the brighter tonal color of E major as the tonic key. This distant tonal relation motivates the emphasis, in the main theme of the rondo finale, on the semitone G–A![]() : the prominent G: from the Largo is thereby reinterpreted as A

: the prominent G: from the Largo is thereby reinterpreted as A![]() in the key of C minor. Beethoven’s rondo design makes room for a dream-like recall of E major in the central section – a glimpse of the slow movement seen through the veil of the rondo theme. The Presto coda, on the other hand, offers a final resolution of the crucial A

in the key of C minor. Beethoven’s rondo design makes room for a dream-like recall of E major in the central section – a glimpse of the slow movement seen through the veil of the rondo theme. The Presto coda, on the other hand, offers a final resolution of the crucial A![]() as G

as G![]() , this time not in E major but in the major mode of the tonic, C. The expressive atmosphere of the coda is unmistakably that of the opera buffa

finale; comic wit and jubilation crown the denouement of this drama in tones.

, this time not in E major but in the major mode of the tonic, C. The expressive atmosphere of the coda is unmistakably that of the opera buffa

finale; comic wit and jubilation crown the denouement of this drama in tones.

Beethoven completed his Fourth Concerto in 1806; it was first performed together with the Fourth Symphony at the palace of Prince Joseph Lobkowitz in March 1807. Like several other works from this period, this concerto displays a quality of spacious lyrical serenity. In the opening Allegro moderato, Beethoven gives special prominence to the dialogue between solo and tutti by beginning with a short piano passage, whose initial G major sonority is reinterpreted with wonderful sensitivity by the strings on a B major harmony, marked pianissimo . At the recapitulation, by contrast, this meditative opening by the soloist is recast as a more forceful gesture, while the ethereal inflection in B major is shared between the piano and orchestra.

According to a tradition stemming from Liszt and others, the Andante con moto is associated with Orpheus taming the Furies. 17 In this movement, the classical topos juxtaposing stark, unharmonized unisons and plaintive, harmonized lyricism is imposed on the relationship between tutti and soloist, investing the music with a mythic aura. Beethoven bases the movement on the principle of gradual transformation, whereby the soloist gradually gains primacy over the orchestra. After having subdued the antagonists, the soloist then exploits them as audience for an unforgettable climactic message – a cadenza featuring a loud, sustained trill. The searing intensity of this cadenza is the apex and turning-point of the entire concerto.

The vivacious rondo finale shows a special richness of thematic material. The main theme has a dance-like character and begins not in the tonic G major but in C major. The transitional and developmental passages emphasize a dramatic exchange between the piano and orchestra, whereas the focus of inward expression is a dolce subject in which the solo piano presents two contrapuntal lines with a vast gap in register, supported by a deep pedal point in the strings. The reinterpretation of this expressive dolce theme in different keys is a prominent feature of the recapitulation and cadenza. The transition to the coda is marked by that specialty of Beethoven’s piano playing showcased in each movement of this great work – the triple trill – and the final Presto section resolves the main theme to the tonic G major with irresistible energy and compelling finality.

The so-called “Emperor” Concerto from 1809 represents a pinnacle of Beethoven’s pianistic virtuosity and a major monument of his “heroic” style cast in the same key as the Eroica

Symphony, E![]() major. Its outer movements assume a majestic character, with rhythmic figures evocative of military style. This Fifth Concerto stems from that point in Beethoven’s career when the composer curtailed his own solo performances on account of his incurable deafness. Cadenzas are now no longer left open to possible extemporization; at the end of the first movement, Beethoven explicitly instructs performers not to play their own cadenza, but inserts the cadenza-like passage to be played right into the score. The opening Allegro actually begins with an impressive cadenza-like passage, which is reaffirmed at the outset of the recapitulation.

major. Its outer movements assume a majestic character, with rhythmic figures evocative of military style. This Fifth Concerto stems from that point in Beethoven’s career when the composer curtailed his own solo performances on account of his incurable deafness. Cadenzas are now no longer left open to possible extemporization; at the end of the first movement, Beethoven explicitly instructs performers not to play their own cadenza, but inserts the cadenza-like passage to be played right into the score. The opening Allegro actually begins with an impressive cadenza-like passage, which is reaffirmed at the outset of the recapitulation.

In the solo exposition of the opening Allegro, the pianist presents a transparent, pianissimo

subject in B minor and C![]() major, thereby presaging the Adagio un poco mosso in B major, the enharmonic equivalent of C

major, thereby presaging the Adagio un poco mosso in B major, the enharmonic equivalent of C![]() . In the overall design of the concerto this serene slow movement in B major acts as an immense parenthesis. Its mood of dream-like reflection is dissipated with wonderful sensitivity at the transition to the festive rondo finale, in which appearances of an energetic round-dance are interspersed with more playful, dolce

subsidiary themes. As in the first movement, Beethoven employs here a wide range of contrast: the dolce

second subject contains hesitating phrases and transparent textures, whereas in the coda, the music reaches a surprising still point as the music slows to Adagio. Even the piano seems to fall mute, as only the rhythmic ostinato is still heard softly in the timpani. Then the soloist caps the finale with an exciting chain of rapid rising scales, leading to the closing orchestral fanfares glorifying the rhythm of the dance.

. In the overall design of the concerto this serene slow movement in B major acts as an immense parenthesis. Its mood of dream-like reflection is dissipated with wonderful sensitivity at the transition to the festive rondo finale, in which appearances of an energetic round-dance are interspersed with more playful, dolce

subsidiary themes. As in the first movement, Beethoven employs here a wide range of contrast: the dolce

second subject contains hesitating phrases and transparent textures, whereas in the coda, the music reaches a surprising still point as the music slows to Adagio. Even the piano seems to fall mute, as only the rhythmic ostinato is still heard softly in the timpani. Then the soloist caps the finale with an exciting chain of rapid rising scales, leading to the closing orchestral fanfares glorifying the rhythm of the dance.

Beethoven’s legacy of sonatas is so vast and significant that a short chapter cannot possibly do it justice. We shall focus here on selected representative works, including the contrasted trilogy of works he published as Opus 2 in 1795, the two monumental sonatas from about a decade later – the “Waldstein” and “Appassionata” Sonatas – and the superbly integrated final sonata trilogy from 1820–22: opp. 109, 110, and 111. Each of the op. 2 sonatas is a highly profiled individual, and their resourceful treatment of form and texture demonstrates Beethoven’s early mastery of the genre. The F minor Sonata op. 2 no. 1 shows a terse dramatic concentration, whereas the second sonata, in A major, is more expansive and radiant in character, and the C major Sonata op. 2 no. 3 is brilliant and virtuosic, studded with cadenzas in the outer movements.

The opening Allegro of the F minor sonata is dominated by Beethoven’s favorite procedure of rhythmic foreshortening, under which phrases are divided into progressively smaller units.

18

Such foreshortening contributes to the inexorable drive of the music. The opening gesture – a rising staccato arpeggiation to a turn figure in the right hand, punctuated by syncopated chords in the left – is stated on the tonic and then on the dominant (Example 7.1

). These two-measure units are then compressed to single bars, half-bars and single beats before the process dissolves into silence – a fermata in the eighth measure. At the same time, Beethoven emphasizes the melodic ascent from A![]() to B

to B![]() , highest tones in the right hand, reaching a climax at the broken chord with the highest tone C played fortissimo

– a sonority that is itself a compression of the initial rising arpeggio. The opening salvo of Beethoven’s very first sonata is a classic example of dynamic forward impulse shaped in sound.

, highest tones in the right hand, reaching a climax at the broken chord with the highest tone C played fortissimo

– a sonority that is itself a compression of the initial rising arpeggio. The opening salvo of Beethoven’s very first sonata is a classic example of dynamic forward impulse shaped in sound.

Example 7.1 Piano Sonata op. 2 no. 1, mvt. 1, mm. 1–11

The second movement is a spacious Adagio in F major, which indulges at times in ornate melodic decorations and an almost orchestral rhetoric. Beethoven drew motivic material for this slow movement from his Piano Quartet in C major WoO 36 no. 3, written a decade earlier at Bonn. In the third movement, a minuet in F minor, Beethoven plays tricks with a conventional cadence formula in a spirit of Haydnesque wit. The Prestissimo finale is in sonata form of a special type. In the exposition and recapitulation, the arpeggios from the opening Allegro become an agitated texture in triplets supporting powerful chords in the treble. In the development, by contrast, an expressive tune emerges in A![]() major that is adorned in melodic variations. The development thus becomes the sonata’s last focus of

lyricism before the music re-enters the turbulent dramatic idiom in F minor. The overall plan of this unusual movement distantly foreshadows Beethoven’s only other sonata in F minor, the “Appassionata” op. 57.

major that is adorned in melodic variations. The development thus becomes the sonata’s last focus of

lyricism before the music re-enters the turbulent dramatic idiom in F minor. The overall plan of this unusual movement distantly foreshadows Beethoven’s only other sonata in F minor, the “Appassionata” op. 57.

Each of Beethoven’s sonatas of op. 2 expands the conventional three-movement Classical design to four movements, with a Minuet and Trio in penultimate position. 19 The opening Allegro vivace of op. 2 no. 2 in A major also audaciously expands the sonata design itself. At the beginning of the second subject group, the music seemingly comes to rest in E minor, the dominant key. Instead of presenting a “theme” at this juncture, Beethoven offers modulating sequences on a chromatically rising bass. This pattern carries the music through the most remote keys, while the thematic material is gradually curtailed through a dramatic process of rhythmic foreshortening. The progression soon grinds to a halt, dwelling on the semitone E to D: (Example 7.2 ). Then, to fill the void, a motive drawn from the opening theme intrudes rambunctiously in the depths of the bass, with almost grotesque effect. Beethoven savors this paradoxical moment to the fullest by playfully reiterating the pivotal E–D: semitone in the high register, before the music finally bursts into the sought-after E major in a spirit of unbuttoned revelry.

Example 7.2 Piano Sonata op. 2 no. 2, mvt.1, mm.57–85

The slow movement in D major, marked Largo appassionato, has a noble, hymn-like character. Beethoven effectively varies the chorale-like main theme, juxtaposing somber massiveness in the minor mode with a transparent, almost luminescent final variation that leads into a meditative coda. Like the first movement, the scherzo and rondo finale of op. 2 no. 2 feature motives based on rising arpeggios, which Beethoven develops here in a lightly sensuous, scintillating manner, quite unlike op. 2 no. 1 . The trio of the scherzo and contrasting theme of the rondo take on a darker, stern character in A minor, laced with dissonance and chromaticism. The closing Grazioso movement of the A major sonata is the first great rondo finale in Beethoven’s sonatas, a worthy forerunner of the gracious closing movements of op. 7, op. 22, and op. 90.

In composing the opening movement of his third sonata, Beethoven skillfully re-worked material from his early piano quartet, the same piece from which he had borrowed for the Adagio of op. 2 no. 1. The opening Allegro con brio of op. 2 no. 3 displays Beethoven’s pianistic virtuosity: it abounds in chains of broken octaves, arpeggios, and trills. Beethoven begins with a measured double trill played on the tonic and then on the dominant; the interval of a third elaborated here resurfaces over and over in the brilliant ensuing passage-work. After this bravura beginning, the group of subsidiary themes offers a varied succession of instrumental colors – an oboe followed by a flute; and a brief orchestral tutti leading into a small string ensemble, before the virtuoso pianist reappears. The development offers a coy false recapitulation in D major that is overturned with almost violent energy, as the thirds are hammered out in syncopated octaves in both hands. The coda re-examines the material of the development, leading through a cadenza and reprise of the main theme to the emphatic close.

What follows is one of the most moving inspirations in early Beethoven. He places the ensuing Adagio in a distant key – E major. The contrast in tonal color casts a dream-like veil over the delicate lyricism of the slow theme. When Beethoven arrives at the cadence in m. 11, however, this aura vanishes; the theme is unable to sustain a resolution. Instead, Baroque-style figuration emerges in the minor, with deep bass octaves and expressive inflections in the high register. The transition is laden with tragic overtones. The scherzo of op. 2 no. 3 also juxtaposes conflicting perspectives, but with an entirely different result – one of Beethoven’s first gems of comic music. This Allegro has a jocular character, but the gaiety of

the opening music is soon pitted against mock bluster in the minor. At the climax, the music seems to be imprisoned within the minor, unable to find the door to C major that will open the ensuing reprise of the scherzo. The humor persists in Beethoven’s coda, as the right hand insists on the major mode of C at the same time as the left persists in the minor, stressing A![]() to G, and then D

to G, and then D![]() to C.

20

to C.

20

The sonata-rondo finale restores the virtuosic tone of the opening movement. This Allegro assai sports a dazzling pianistic technique: the main theme begins with rapid parallel chords of the sixth, a configuration that is changed to octaves for acoustical reasons whenever the subject appears in the low register. The character is capriciously humorous; each new appearance of the principal theme is enriched by surprising new variants. Beethoven caps his finale with a coda beginning with the main theme played in the left hand, under an extended trill. The ensuing cadenza-like passages strive upward to reach a linear goal on F, a fourth higher. As first they fail: a triple trill fades into silence; groping attempts to reassert the head of the theme stumble into the “wrong” keys, A major and A minor. Does this passage recall the amusing search for the “door” in Beethoven’s scherzo? The music at last seizes hold of the high F, unlocking the original tonality and tempo in its jubilant rush to the conclusion.

The most outstanding of Beethoven’s other sonatas from the 1790s is perhaps the Sonata in D major op. 10 no. 3, and particularly its profound Largo e mesto, in D minor. Together with the Sonate Pathétique op. 13, this somber slow movement exemplifies the young Beethoven’s impressive command of tragic expression in music. Friedrich Schiller, in his 1793 essay Über das Pathetische , offers a lucid discussion of tragic art whose conceptual framework applies well to Beethoven. Schiller stresses that the depiction of suffering as such is not the purpose of art; what must be conveyed is resistance to the inevitability of pain or despair, for in such resistance is lodged the principle of freedom. Such an existential conflict seems encoded in the rhetorical structure of the Largo e mesto, in sonata form. The opening theme develops a slow melodic turning figure that is weighed down by thick, dark chords in the bass. The ensuing theme contains vocal accents and inflections in the higher register. Yet this yearning personal expression is consistently contradicted in this Largo by emphatic dissonant chords and by a starkness that often signals the deathlike void of silence. At the outset of the development, the music moves with hopefulness into F major before this brighter, optimistic tone is contradicted by accented dissonant sonorities. The following expressive treble figuration in thirty-second notes floats above long pedal points in the bass, whose seemingly inevitable resolution sounds like an unfolding of irreversible fate. Beethoven exploits here a wide registral gap between the plaintive figures in the treble and the low, thick sonorities rooted on D that will ground the imminent recapitulation. At the registral descent preceding the recapitulation, the sighing figures fade into a silence, which is broken only by the anguished gesture of a rising diminished seventh interval.

The climax of the narrative design of the Largo e mesto occurs in the weighty coda, beginning where the cadential progression in D minor is completed with a vast drop in register into the depths of the bass, with an accompaniment in undulating sextuplets in the right hand (Example 7.3

). Here the turning figure gravitates downwards in sequence, reaching a harrowing low climax on G![]() before a chromatically ascending bass-line strives upward to reach the register that had been prepared already in m. 64. In completing the cadence into the bare octave D in m. 76, Beethoven subordinates and merges the continuity of plaintive vocal figures into the stark unharmonized unison followed by silence. The poignancy of this passage lies in its silencing of the implied human voice (Example 7.4

). The movement ends with references to fragments from the opening theme and allusions to the registral disparities between its low chords and the extracted motive of a semitone in the highest register. Remarkably, the second and third notes of the turning motive – C: and D – are stifled into the evocative silence of m.76, only to echo again in the last two measures. To the end, Beethoven maintains the expressive dialectic between the fragility

of human expressivity and the immovable reality of termination. The full-voiced, accented diminished seventh chords with which the exposition and recapitulation peak (mm.23–25; 62–64) are caught between these poles, laden with anguish and unfulfilled yearning. In Schiller’s terms, resistance is manifest, although incapable here of transformation and hence doomed to melancholy resignation.

before a chromatically ascending bass-line strives upward to reach the register that had been prepared already in m. 64. In completing the cadence into the bare octave D in m. 76, Beethoven subordinates and merges the continuity of plaintive vocal figures into the stark unharmonized unison followed by silence. The poignancy of this passage lies in its silencing of the implied human voice (Example 7.4

). The movement ends with references to fragments from the opening theme and allusions to the registral disparities between its low chords and the extracted motive of a semitone in the highest register. Remarkably, the second and third notes of the turning motive – C: and D – are stifled into the evocative silence of m.76, only to echo again in the last two measures. To the end, Beethoven maintains the expressive dialectic between the fragility

of human expressivity and the immovable reality of termination. The full-voiced, accented diminished seventh chords with which the exposition and recapitulation peak (mm.23–25; 62–64) are caught between these poles, laden with anguish and unfulfilled yearning. In Schiller’s terms, resistance is manifest, although incapable here of transformation and hence doomed to melancholy resignation.

Example 7.3 Piano Sonata op. 10 no. 3, mvt. 2, mm. 63–68

Example 7.4 Piano Sonata op. 10 no. 3, mvt. 2, mm. 73–87

An attitude of resistance, even defiance, is more evident in the famous Sonate Pathétique, published in 1799. In the introductory Grave of the first movement, this resistance to suffering is implied in the contrast between an aspiring, upward melodic unfolding and the leaden weight of the C minor tonality, with its emphasis on dissonant diminished seventh chords. The rising contour and harmonic dissonances of the Grave are then transformed into forceful accents in the turbulent main theme of the ensuing Allegro di molto e con brio. Beethoven later recalls the Grave to preface the development and coda, underscoring the juxtaposition of tempi as a germinal idea of the movement.

A even more concentrated contrast of tempi launches the most celebrated of the sonatas from Beethoven’s pivotal transitional period around 1802: the so-called “Tempest” Sonata in D minor op. 31 no. 2. Innovations also characterize the immediately preceding sonatas: in the Sonatas in A![]() major op. 26 and in E

major op. 26 and in E![]() major op. 27 no. 1, Beethoven dispenses with any movements in sonata form, whereas in the following Sonata in C: minor op.

27 no. 2 (mistitled “Moonlight”), he shapes the three movements into a directional sequence leading from a soft, improvisatory Adagio sostenuto to a turbulent Presto agitato finale, whose sonata design reinterprets the thematic substance of the opening movement. Both of the op. 27 sonatas are labeled “Sonata quasi una Fantasia.” Their quality of extemporization also surfaces in op. 31 no. 2, which begins with a suspended, tonally ambiguous first-inversion dominant chord in Largo tempo, a gesture paired in turn with a driving passage in Allegro tempo. Only at the recapitulation does the Largo reveal its full expressive significance in giving rise to passages of recitative strongly anticipating the setting of “O Freunde, nicht diese Töne!” (“O friends, not these tones!”) in the finale of the Ninth Symphony.

major op. 27 no. 1, Beethoven dispenses with any movements in sonata form, whereas in the following Sonata in C: minor op.

27 no. 2 (mistitled “Moonlight”), he shapes the three movements into a directional sequence leading from a soft, improvisatory Adagio sostenuto to a turbulent Presto agitato finale, whose sonata design reinterprets the thematic substance of the opening movement. Both of the op. 27 sonatas are labeled “Sonata quasi una Fantasia.” Their quality of extemporization also surfaces in op. 31 no. 2, which begins with a suspended, tonally ambiguous first-inversion dominant chord in Largo tempo, a gesture paired in turn with a driving passage in Allegro tempo. Only at the recapitulation does the Largo reveal its full expressive significance in giving rise to passages of recitative strongly anticipating the setting of “O Freunde, nicht diese Töne!” (“O friends, not these tones!”) in the finale of the Ninth Symphony.

The two biggest sonatas of Beethoven’s middle period – the “Waldstein” in C major op. 53, and “Appassionata” in F minor op. 57 – partake of the key symbolism of Beethoven’s opera Fidelio,

which in its original version dates from 1805. If Florestan’s “God! – what darkness here!” might serve as commentary on the conclusion of the “Appassionata,” the choral text “Hail to the day! Hail to the hour!” at the end of Fidelio

might almost be the motto for the jubilant coda of the “Waldstein” finale. Another, more subtle link was signaled by Beethoven’s replacement of the original decorative slow movement of the “Waldstein,” the Andante favori

, by a mysterious, searching Introduzione

, which is related structurally to the music heard at the dungeon scene in the last act of the opera.

21

Donald Francis Tovey wrote that the “Appassionata” is Beethoven’s only work to maintain “a tragic solemnity throughout all its movements,”

22

but the impression of the outer movements is far less solemn than forcefully dramatic. In a perceptive recent study, Gregory Karl has regarded the narrative unfolding of the first movement as “the internal experience of a persona in pursuit of an ideal destined to be crushed by an inscrutable and intractable antagonistic force.”

23

The middle movement is an Andante con moto in D![]() major, whose unfolding variations take on a dream-like quality. As in the “Waldstein” Sonata, this slow middle movement is connected directly to the finale. The serenity of the music is shattered when Beethoven substitutes a dissonant diminished seventh harmony at the implied moment of closure: the moment of tragic reversal is marked by thirteen fortissimo

chords that launch the closing Allegro, ma non troppo.

major, whose unfolding variations take on a dream-like quality. As in the “Waldstein” Sonata, this slow middle movement is connected directly to the finale. The serenity of the music is shattered when Beethoven substitutes a dissonant diminished seventh harmony at the implied moment of closure: the moment of tragic reversal is marked by thirteen fortissimo

chords that launch the closing Allegro, ma non troppo.

Inthe “Waldstein” and “Appassionata,” the sonata has becomea superbly integrated dramatic canvas on an imposing scale. Poised at the beginning of Beethoven’s gradual withdrawal from active solo performing, this pair of sonatas raises the stakes for interpretation, distancing the music from established genre categories and conventions while encouraging the application of the autonomous work-concept – the notion of the artistic masterpiece lifted out of history. Like the Eroica among the symphonies, these two sonatas have taken on a canonical status, profoundly reshaping subsequent expectations about the genre of the Classical piano sonata.

During the ensuing decade, the piano sonata became less conspicuous in Beethoven’s output. He produced another trio of works around 1809: op. 78 in F: major, op. 79 in G major, and op. 81a, the Lebewohl or “Farewell” Sonata. The Lebewohl bears the imprint of the turbulent political events of 1809, when Napoleon’s armies invaded Austria and occupied Vienna after bombarding the city. Many of Beethoven’s friends fled from Vienna, including his student and patron the Archduke Rudolph, to whom the sonata is dedicated. Beethoven entered the dates of the Archduke’s departure and return into the score and allowed the emotional progression of “farewell–absence–return” (“Lebewohl– Abwesenheit–Wiedersehen”) to determine the basic character of the three movements. Yet the Lebewohl is far from being a merely programmatic, illustrative work, in the manner of Beethoven’s later “Battle Symphony,” Wellington’s Victory op. 91, from 1813. Its most impressive passages tend to do double duty, bending musical inspirations to symbolic ends. F or instance, the harmonic boldness characteristic of this sonata is most of all evident in the coda of the opening movement, where the tonic and dominant are repeatedly sounded together. Here the imitations of the original “Lebewohl” motto seem to recede into the distance, implying that the departure has taken place.

Beethoven’s next sonatas, the works in E minor op. 90, from 1814, and in A major op. 101, from 1816, are connected to his distinguished piano student Baroness Dorothea Ertmann. Ertmann was one of the first pianists to become known specifically for her interpretations of Beethoven; her intelligent and sensitive performances so delighted him that the appreciative composer once dubbed her his “dear, valued Dorothea-Cäcilia.” 24 In a letter from 1810, Wilhelm Karl Rust commented about the performances of the Baroness: “She always makes music entirely as I imagine it. Either she plays me a Beethoven sonata that I select, or I play her favorite fugues by Handel and Bach.” 25 Ertmann was especially recognized for her playing of op. 90, whose second, final movement is the most Schubertian movement in Beethoven, a luxurious rondo dominated by many appearances of a spacious cantabile theme. According to Anton Schindler, whose testimony can be trusted in this instance, “she nuanced the often recurring main motive of this movement differently each time, so that it took on first a coaxing and caressing, and later a melancholy character. In this way the artist was capable of playing with her audience.” 26 More evidence of Beethoven’s appreciation of Ertmann is his dedication to her of the A major Sonata op. 101, one of the most technically and psychologically challenging of all the sonatas.

Beethoven advanced beyond even this aesthetic framework in the largest of all his sonatas, the “Hammerklavier” in B![]() major op. 106. He described op. 106 as “a sonata that will keep pianists busy when it is played 50 years hence”

27

– a fairly accurate prediction, since apart from Franz Liszt, Clara Schumann and Hans von Bülow, few pianists tackled the immense challenges of this great sonata before the last decades of the nineteenth century. Pieces like the “Hammerklavier” Sonata and the “Diabelli” Variations tested the viability of the work-concept to an even greater extent by pushing the conditions for adequate performance into an unspecified future, according to Beethoven’s favorite dictum, ars longa, vita brevis

(“art is long, life is short”).

major op. 106. He described op. 106 as “a sonata that will keep pianists busy when it is played 50 years hence”

27

– a fairly accurate prediction, since apart from Franz Liszt, Clara Schumann and Hans von Bülow, few pianists tackled the immense challenges of this great sonata before the last decades of the nineteenth century. Pieces like the “Hammerklavier” Sonata and the “Diabelli” Variations tested the viability of the work-concept to an even greater extent by pushing the conditions for adequate performance into an unspecified future, according to Beethoven’s favorite dictum, ars longa, vita brevis

(“art is long, life is short”).

The “Hammerklavier” is the only one of the late sonatas to revisit the four-movement plan characteristic of the early sonatas, such as op. 2, op. 7, and op. 10 no. 3. An extraordinary role is assumed in each movement by B minor – a tonality Beethoven once described as a “black key.” B minor functions in the “Hammerklavier” like a focus of negative energy pitted against the B![]() major tonic, creating a dramatic opposition with far-reaching consequences. In op. 106, the conventional order of the inner movements is reversed, with the scherzo placed before the great Adagio sostenuto – the longest slow movement in Beethoven. Its tonality is F: minor, enharmonically a third lower than the tonic B

major tonic, creating a dramatic opposition with far-reaching consequences. In op. 106, the conventional order of the inner movements is reversed, with the scherzo placed before the great Adagio sostenuto – the longest slow movement in Beethoven. Its tonality is F: minor, enharmonically a third lower than the tonic B![]() , poised between the overall tonic of the work and the focus of contrary forces in B mino. Irn the ensuing slow introduction to the fugal finale, Beethoven distills the intervallic basis of the whole sonata, reducing the music to a mysterious, underlying level of content consisting solely of a chain of thirds in the bass, accompanied by soft, hesitant chords in the treble.

28

This descending chain of thirds is interrupted three times by brief glimpses of other music, the last of which is reminiscent of Johann Sebastian Bach. The music thus suggests a search toward new compositional possibilities, with the implication that Baroque counterpoint is transcended by the new contrapuntal idiom embodied in the fugal finale, whose fiery defiance of expression poses special challenges for listeners and performers alike.

, poised between the overall tonic of the work and the focus of contrary forces in B mino. Irn the ensuing slow introduction to the fugal finale, Beethoven distills the intervallic basis of the whole sonata, reducing the music to a mysterious, underlying level of content consisting solely of a chain of thirds in the bass, accompanied by soft, hesitant chords in the treble.

28

This descending chain of thirds is interrupted three times by brief glimpses of other music, the last of which is reminiscent of Johann Sebastian Bach. The music thus suggests a search toward new compositional possibilities, with the implication that Baroque counterpoint is transcended by the new contrapuntal idiom embodied in the fugal finale, whose fiery defiance of expression poses special challenges for listeners and performers alike.

Beethoven’s final sonata trilogy, opp. 109–11, embodies other kinds of narrative designs in which the finale becomes center of gravity of the whole. In contrast to earlier works, such as the sonatas of op. 2, these final sonatas project a directional process that is sustained across the individual movements, ultimately reaching fulfillment in culminations of lyric euphoria. The finales of opp. 109 and 111 consist of variations on themes in a slow tempo, whereas the fugal sections in the finale of op. 110 are metrically co-ordinated with the slow stanzas of the Arioso dolente, marked Adagio, ma non troppo. The last movement of op. 109 begins and closes with a sublime, sarabande-like theme, whose motivic substance and melodic outline are foreshadowed in the opening movement. Here, as in the two companion sonatas, the coda of the first movement takes on an anticipatory role, tentatively foreshadowing the finale and assuming thereby a character of unfulfilled yearning. 29

In the finale of op. 110, in A![]() major, Beethoven interweaves a lamenting Arioso dolente

and spiritualized fugue, creating an unusual framework with parallels to the alternation of Agnus Dei and Dona nobis pacem in the last movement of his Missa solemnis

. Both the depressive modality of the Arioso

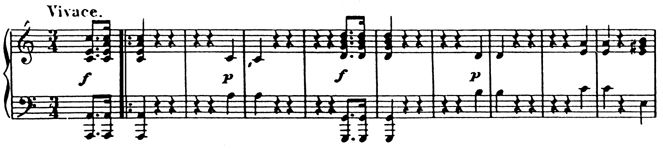

and the aspiring lyricism of the fugue are foreshadowed in parts of the first movement, but it is the comic scherzo-like second movement (Allegro molto) that seems to exert influence at the most crucial juncture: the double-diminution passage of the second fugue (Example 7.5a

). This passage signals the imminent re-attainment of the tonic key of A

major, Beethoven interweaves a lamenting Arioso dolente

and spiritualized fugue, creating an unusual framework with parallels to the alternation of Agnus Dei and Dona nobis pacem in the last movement of his Missa solemnis

. Both the depressive modality of the Arioso

and the aspiring lyricism of the fugue are foreshadowed in parts of the first movement, but it is the comic scherzo-like second movement (Allegro molto) that seems to exert influence at the most crucial juncture: the double-diminution passage of the second fugue (Example 7.5a

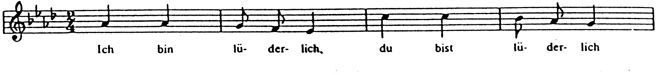

). This passage signals the imminent re-attainment of the tonic key of A![]() major and emergence of the triumphant closing lyric ascent. It also generates, in its radical structural compression of the fugue subject, deleting the second of the three rising fourths, a level of rhythmic energy that sustains the rapid figuration of the final passages, giving the effect that the theme is glorified by its own substance. The Meno allegro passage recalls a comic allusion in the Allegro molto to a folksong quotation, “Ich bin lüderlich, du bist lüderlich” (“I’m dissolute, you’re dissolute”) (Examples 7.5b, c).

The import of Beethoven’s inscription for the entire transitional passage, “nach u. nach sich neu belebend” (“gradually coming anew to life”), is embodied in this musical progression. The abstract contrapuntal matrix beginning with the inverted subject is gradually infused with a raw but vital energy, which arises not naturally through traditional fugal procedures but only through an exertion of will that strains those processes to their limits.

major and emergence of the triumphant closing lyric ascent. It also generates, in its radical structural compression of the fugue subject, deleting the second of the three rising fourths, a level of rhythmic energy that sustains the rapid figuration of the final passages, giving the effect that the theme is glorified by its own substance. The Meno allegro passage recalls a comic allusion in the Allegro molto to a folksong quotation, “Ich bin lüderlich, du bist lüderlich” (“I’m dissolute, you’re dissolute”) (Examples 7.5b, c).

The import of Beethoven’s inscription for the entire transitional passage, “nach u. nach sich neu belebend” (“gradually coming anew to life”), is embodied in this musical progression. The abstract contrapuntal matrix beginning with the inverted subject is gradually infused with a raw but vital energy, which arises not naturally through traditional fugal procedures but only through an exertion of will that strains those processes to their limits.

Example 7.5

(a) Piano Sonata op. 110, mvt. 3, mm. 165–72

( b) Piano Sonata op. 110, mvt. 2, mm. 17–21

(c) Song, “Ich bin lüderlich”

The two-movement design of the final Sonata in C minor op. 111 provoked Beethoven’s publisher Moritz Schlesinger to inquire whether a third movement had been omitted from the manuscript. In the same vein, Thomas Mann, in the eighth chapter of his novel Doktor Faustus,

has the fictional character Wendell Kretzschmar lecture on “why Beethoven wrote no third movement to the Piano Sonata Opus 111.” A proper answer to this question would go to the heart of the aesthetic of Beethoven’s third period. The turbulent strife of Beethoven’s life-long preoccupation with the “C minor mood” seems to reach a climax in the opening movement of the sonata. Yet the fleeting appearance of the lyrical second theme in A![]() major, and its more sustained passages in C major and F minor in the recapitulation, represent a foreshadowing of the character of the Arietta

, and they accordingly slow the music to Adagio. The plagal cadences

to C major in the coda build a bridge from the Allegro to the finale. Then the tension of the first movement is resolved, once and for all, as the unfolding variations on a lyric Arietta

in C major achieve a synthesis of Being and Becoming. The progressive rhythmic subdivisions in the variations carry the music through the utmost agitation in variation 3 to the suspended, uncanny final passages. When the rhythmic intensification and registral ascent reach their climax, the original theme is recaptured, glorified by sustained trills and ethereal textures that music had never known before.

major, and its more sustained passages in C major and F minor in the recapitulation, represent a foreshadowing of the character of the Arietta

, and they accordingly slow the music to Adagio. The plagal cadences

to C major in the coda build a bridge from the Allegro to the finale. Then the tension of the first movement is resolved, once and for all, as the unfolding variations on a lyric Arietta

in C major achieve a synthesis of Being and Becoming. The progressive rhythmic subdivisions in the variations carry the music through the utmost agitation in variation 3 to the suspended, uncanny final passages. When the rhythmic intensification and registral ascent reach their climax, the original theme is recaptured, glorified by sustained trills and ethereal textures that music had never known before.

Already in his childhood, Beethoven had improvised variations on popular melodies by other composers. After his move to Vienna in 1792, he wrote out numerous sets of piano variations based on themes by such diverse composers as Dittersdorf, Grétry, Haibel, Mozart, Paisiello, Righini, Salieri, Süssmayr, and Winter. 30 The very closeness of these pieces to improvisation may help explain his reluctance to assign them opus numbers. Only in 1802 did he lift the variation genre into the mainstream of this artistic production with two sets of piano variations on original themes, op. 34 and op. 35. As Beethoven pointed out in a letter to his publisher, these works are “noticeably” different from his earlier variation sets; he therefore assigned them opus numbers, and, as he put it, “included them in the proper numbering of my great works, all the more, since the themes as well are by me.”

Beethoven had used the theme of the Fifteen Variations and Fugue in E![]() major op. 35 twice previously: as the seventh of the Contredances for Orchestra WoO 16, and at the conclusion of the Prometheus

Ballet op. 43, where Prometheus is celebrated by his two “creatures” – the original representatives of humanity. Asense of creative evolution is reflected here musically in the unusual compositional strategy of starting with the bass alone: only after several variations on the basso del tema

does the composite theme emerge. The fragmentary, even bizarre effect of starting with only the bass is linked to the creation myth, whereby the awkward clay figures of Prometheus are gradually instilled with human life. The initial quality of unpredictability is sustained throughout this impressive work, which assumed even more importance by serving as the model for the Eroica

finale, the seminal movement of the symphony, as Lewis Lockwood as shown.

31

major op. 35 twice previously: as the seventh of the Contredances for Orchestra WoO 16, and at the conclusion of the Prometheus

Ballet op. 43, where Prometheus is celebrated by his two “creatures” – the original representatives of humanity. Asense of creative evolution is reflected here musically in the unusual compositional strategy of starting with the bass alone: only after several variations on the basso del tema

does the composite theme emerge. The fragmentary, even bizarre effect of starting with only the bass is linked to the creation myth, whereby the awkward clay figures of Prometheus are gradually instilled with human life. The initial quality of unpredictability is sustained throughout this impressive work, which assumed even more importance by serving as the model for the Eroica

finale, the seminal movement of the symphony, as Lewis Lockwood as shown.

31

It may seem surprising that Beethoven’s greatest variation set reverts to the use of a pre-existing theme, and a rather trivial one at that. The theme stems from the publisher Anton Diabelli, who in 1819 asked numerous composers to each contribute a variation; the collective project was designed to generate publicity for his firm. Beethoven initially refused. He disdained Diabelli’s waltz as a “cobbler’s patch” (“Schusterfleck”) on account of its mechanical sequences, and did not overlook its trivial aspects, such as the prominent repeated chords that are played tenfold with a crescendo in each of the two opening phrases. Despite this initial reaction, Beethoven soon responded to Diabelli’s invitation with a creative brainstorm: by the summer of 1819 he had composed not one, but a draft version including already twenty-three variations. 32 Only in 1823 did Beethoven complete this colossal work, which has been praised by Hans von Bülow as a “microcosm of Beethoven’s genius” 33 and by Alfred Brendel as “the greatest of all piano works.” 34

In the end, even the banality of the theme assumed an important role. By subjecting Diabelli’s waltz to parody and caricature, and poking fun at its shortcomings, Beethoven drew the waltz more deeply into the inner workings of the work as a whole. In variation 13, for instance, Beethoven dissolves these repetitions into silence, whereas in variation 21 he mercilessly exaggerates the banality of the repeated chords (Examples 7.6a, b, c). A comic obsessiveness characterizes variation 9, which is based throughout on the turn figure from the head of the theme. One of Beethoven’s wittiest inspirations is the reference, in the unison octaves of variation 22, to “Notte e giorno faticar” from the beginning of Mozart’s Don Giovanni . This allusion is brilliant not only through the musical affinity of the themes – which share, for example, the same descending fourth and fifth – but through the reference to Mozart’s Leporello. Beethoven’s relationship to his theme, like Leporello’s relationship to his master, is critical but faithful, inasmuch as he exhaustively exploits its motivic components. And like Leporello, the variations after this point gain the capacity for disguise. Variation 23 is an etude-like parody of pianistic virtuosity alluding to the “Pianoforte-Method” by J. B. C ramer, whereas variation 24, the Fughetta, shows an affinity in its intensely sublimated atmosphere to some organ pieces from the third part of the Clavierübung by J. S. Bach.

Example 7.6 (a) “Diabelli” Variations op. 120, theme

(b) Variation 13

(c) Variation 21

The “Diabelli” Variations culminate in a Mozartian minuet whose elaboration through rhythmic means leads, in the coda, to an ethereal texture strongly reminiscent of the famous Arietta movement from Beethoven’s own last sonata, op. 111, composed in 1822. Herein lies the final surprise: the Arietta movement, itself influenced by the “Diabelli” project, became in turn Beethoven’s model for the last of the “Diabelli” Variations. The end of the series of allusions thus became a self-reference and final point of orientation within an artwork whose vast scope ranges from ironic caricature to sublime transformation of the commonplace waltz. In the last moments, Beethoven briefly alludes to the repeated chords from the waltz, and he concludes the cycle in the middle of Diabelli’s thematic structure, poised on a weak beat. The unresolved tension of this surprising final chord reminds us that Beethoven’s work is one of created, not congenital, harmony, and that in these closing bars we have reached “an end without any return” (“ein Ende auf Nimmerwiederkehr”), in the words of Thomas Mann’s Kretzschmar in Doktor Faustus.

Despite the importance of improvisation to Beethoven, he published only one fantasy for piano solo: op. 77 from 1809.

35

This piece is probably a revised version of the improvised solo fantasy Beethoven played at his famous Akademie

concert of 22 December 1808, when the Fifth and Sixth Symphonies, the Fourth Piano Concerto, and the Choral Fantasy were first performed. The op. 77 Fantasy culminates in a set of variations in B major, following a free opening section abounding in thematic contrasts and sudden modulations, in a style reminiscent of C. P. E. Bach. The initial gesture of this work is a rapid descending scale, which seems torn, as it were, from the celestial ether; rather than support its key, G minor, Beethoven proceeds to the remote D![]() major, the key of the contrasting lyrical theme. The op. 77 Fantasy and the opening solo introduction to the Choral Fantasy both offer insight into Beethoven’s considerable powers of invention outside the formal demands of the Classical sonata style.

major, the key of the contrasting lyrical theme. The op. 77 Fantasy and the opening solo introduction to the Choral Fantasy both offer insight into Beethoven’s considerable powers of invention outside the formal demands of the Classical sonata style.

Beethoven also made signal contributions in the category of the bagatelle: a short, intimate piano piece of lyrical or whimsical character. He had a long-standing interest in such pieces, some of which were connected to his larger compositions. The dance-like Allegro with Minore used as the penultimate movement of his Piano Sonata in E![]() major op. 7 was originally sketched as a “bagatelle” independent from the sonata,

36

and the first movement of the Piano Sonata in E major op. 109 was also originally conceived as a bagatelle.

37

The most familiar of Beethoven’s bagatelles is the popular Für Elise

, which is known in a version dating from

1810. His first collection of such pieces, the Seven Bagatelles op. 33, dates from 1802. Several unpublished bagatelles from earlier years were revised and included in the Eleven Bagatelles of op. 119, brought out in 1823, together with freshly composed pieces, two of which are byproducts of the “Diabelli” Variations.

38

When Beethoven began negotiating the publication of what became op. 119, in 1822, his portfolio of bagatelles contained about a dozen additional pieces, including the Scherzi in C minor WoO 52 and WoO 53, which were originally conceived for the Sonata in C minor op. 10 no. 1, as well as the Allemande in A major WoO 81, which was eventually incorporated into the String Quartet in A minor op. 132.

39

major op. 7 was originally sketched as a “bagatelle” independent from the sonata,

36

and the first movement of the Piano Sonata in E major op. 109 was also originally conceived as a bagatelle.

37

The most familiar of Beethoven’s bagatelles is the popular Für Elise

, which is known in a version dating from

1810. His first collection of such pieces, the Seven Bagatelles op. 33, dates from 1802. Several unpublished bagatelles from earlier years were revised and included in the Eleven Bagatelles of op. 119, brought out in 1823, together with freshly composed pieces, two of which are byproducts of the “Diabelli” Variations.

38

When Beethoven began negotiating the publication of what became op. 119, in 1822, his portfolio of bagatelles contained about a dozen additional pieces, including the Scherzi in C minor WoO 52 and WoO 53, which were originally conceived for the Sonata in C minor op. 10 no. 1, as well as the Allemande in A major WoO 81, which was eventually incorporated into the String Quartet in A minor op. 132.

39

Beethoven’s last important composition for piano, the “Cycle of Bagatelles” op. 126, from 1824, binds a succession of six highly contrasted pieces with the integrative power that had long characterized his multi-movement works in other genres. Lyrical pieces in slow or moderate tempi alternate with more rapid, agitated ones until no. 6, in which a short and furious Presto frames a reflective Andante amabile eocn moto. The play of contrasts and integration is lifted here into the realm of paradox, and Wilfrid Mellers has written that “coming from the greatest of all composers normally concerned with process and progression, this little bagatelle may count as Beethoven’s most prophetic utterance.” 40 Whereas the provocatively mechanistic Presto initially offers the raw material, as it were, out of which the Andante is shaped, the center of the bagatelle visits ethereal textures reminiscent of the Arietta movement of op. 111. Then the process is reversed: the adornments of art are stripped away to reveal the music from the beginning of the Andante followed by the frenetic Presto, whose fanfare of chords closes the piece. Beethoven’s final bagatelle concludes by enacting its own deconstruction, and its circular design symbolizes that imaginative transformation of experience that lies at the foundation of art.