Example 13.1 “Die Liebe des Nächsten” op. 48 no. 2, mm.15–29

BIRGIT LODES

Beethoven lived at a time when Christianity and its institutions were losing much of their power, yet the influence of religion is felt not only in his explicitly sacred and liturgical works but also in works such as the Ninth Symphony, Fidelio , and the “Heiliger Dankgesang” from the A minor String Quartet. Since Beethoven, who was baptized as a Catholic, never really subscribed to any one of the many distinct theological currents of his time, it is difficult to obtain a coherent picture of his religious views from the multiplicity of ideas that, as documentary evidence proves, occupied Beethoven’s interest. 1 Still, a pattern emerges in his independent pursuit of religious questions that is reflected in his choice of texts to set: for him, religion was something not just dogmatically given and represented through the Catholic Church, but rather to be understood from a human perspective and experienced in its relevance to one’s own life – a position that differs as essentially from the Baroque orientation toward the hereafter as from the mysticism and otherworldliness of Romanticism.

With the first unmistakable signs of hearing loss and the deep personal, musical, and ideological crisis that followed, Beethoven began to grapple increasingly with religious ideas. At this time he came to know the Geistliche Oden und Lieder of Christian Fürchtegott Gellert (1st edn., Leipzig, 1757). From these fifty-four texts he chose six with revealing content: “Die Ehre Gottes aus der Natur,” for example, recalls ideas in poems by Christoph Christian Sturm from Betrachtungen über die Werke Gottes im Reiche der Natur ... , a book which he may have encountered while still in Bonn and later definitely read, 2 and “Vom Tode,” to which the ideas of the last section of the Heiligenstadt Testament (October 1802) closely correspond, 3 seems to reflect his preoccupation with thoughts of death.

Gellert’s poems were among the most frequently set texts in the second half of the eighteenth century. 4 C. P.E. Bach composed some of the most remarkable and musically most demanding settings (1758 and 1764), which Beethoven may have known. Bach’s strophic settings are distinguished by an unpretentious tone, a simple and often chorale-like melodic line that is doubled in the treble part of the keyboard, and an almost complete absence of music for keyboard alone. Beethoven broke with this precedent in his own Lieder , which date from between 1798 and 1802. “Bußlied,” the last of Beethoven’s settings, has special significance within his entire song repertory because of its great length and its through-composed bipartite construction. Moreover, in the fast second part, for the first time in the history of the German Lied , a varied, virtuosic piano accompaniment is placed against an unvaried vocal part (compare with the later An die ferne Geliebte op. 98, 1815). Even the first five, despite their simplicity, include more keyboard figuration than the Bach pieces. There are preludes, interludes, and postludes in the piano, and the melody, which is not always identical in the vocal and piano treble parts, contains surprises, such as the large leap in no. 2, m. 10. Despite the regularity of the line lengths and rhythms in the poems, Beethoven varies phrase-lengths (no. 3) or, for expressive purposes, the vocal declamatory rhythms (no. 2). In no. 4 he composed two musical strains for the first two poetic strophes, thus achieving a larger overall form (ABA´). In preparing the songs for publication he shifted “Bußlied,” the most substantial setting, to the end, 5 thus achieving an effective conclusion of the entire group.

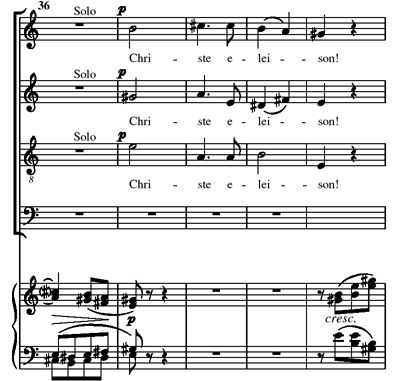

At the same time the songs have conspicuously “religious” traits, especially the first five: contrapuntal textures, the avoidance of melismas and word-repetitions, the preference for unvaried chorale-like rhythms, half notes as the preferred rate of declamation (frequently with an alla breve marking), and even, in no. 2, a postlude for the piano that is reminiscent of a chorale prelude for organ in which the vocal melody is distributed among the parts of the strict contrapuntal texture (Example 13.1 ). In these Lieder , it seems, Beethoven for once consciously wanted to approximate church idioms.

Example 13.1 “Die Liebe des Nächsten” op. 48 no. 2, mm.15–29

Using religious texts in solo songs with piano was not a common practice among Viennese composers, but Beethoven set a number of other such texts in this manner, including “An einen Säugling” WoO 108, 1784?, “Der Wachtelschlag” WoO 129, 1803, “An die Hoffnung” op. 32, 1805, and op. 94, 1815, “Abendlied unterm gestirnten Himmel” WoO 150, 1820. These Lieder , some of which represent his earliest engagement with spiritual themes in music, are relevant in several important ways for his later religious works. In these works, he found musical solutions for certain types of textual ideas that he would later fall back on and develop further: among these are flickering chord repetitions as an image of the stars, 6 a IV–I cadence to end an open statement pointing toward the future (first in the “Bußlied” op. 48 no. 6, then in the Missa solemnis , from the Gloria up to the Agnus), the idea of developing a movement from a single note to which a line is added (op. 48 no. 1, WoO 129, Kyrie of the C major and, modified, the D major Mass; see below) or the vivid musical juxtaposition of the noise of war and trust in God (WoO 129, mm.51 ff.; Missa solemnis , Agnus Dei, mm.338 ff.).

Beethoven may have begun work on his only oratorio, Christus am Ölberge , at the end of 1802, thus only a few months after completing the “Gellert” Lieder . 7 Having recently been employed at Schikaneder’s Theater an der Wien, he glimpsed the possibility of using the theater during the coming Lenten season for an academy in which he would present himself in public for the first time as a vocal composer. The recent introduction of three important oratorios to the Viennese repertory, Haydn’s Seven Words , Creation , and Seasons , which were first performed during Lent in 1796, 1798, and 1801 respectively, posed a challenge to Beethoven’s ambition to establish himself as a composer in all the important genres.

As the subject for his oratorio Beethoven selected an excerpt from the Passion story of Jesus (the prayer on the Mount of Olives in nos.1–3 and the arrest in 4–6). 8 The fact that virtually no oratorio setting of the Passion story had been performed in Vienna during the preceding years in itself suggests that the choice of text was not a matter of convention, but rather had personal meaning for him. The plot deviates from the traditional story in a significant way: the events are more powerfully centered on Jesus the person, who is presented as an individual in all his changing feelings. Certain phrases in the Heiligenstadt Testament and Beethoven’s letters from the time closely resemble the language and the ideas from passages in the oratorio, providing strong evidence that in his own time of crisis Beethoven identified with the figure of Jesus. 9

In Jesus he saw an exemplary person whose moral precepts he wished to follow. The “godliness” of Jesus was not the central idea for him, and there is even evidence that he doubted this aspect of Catholic theology. 10 Instead, he stressed the Christian concept of love. This emerges clearly in the recitative and trio from no. 6, in which Beethoven’s music sensitively expresses Peter’s angry rejection of Jesus’s message of love (see mm. 74 ff.) – a very human reaction – but after Jesus has instructed him again to love his enemies (now in recitative-like direct speech rather than an aria) Peter finally agrees to preach this holy law.

Many unusual features of the work, some of which are still controversial, follow from the oratorio’s emphasis on the human side of Jesus:

Rather than the usual oratorio bass, Jesus is set as an operatic tenor/ suffering hero; in his first appearance he sings a recitative with a dramatic aria and solo cadenza and later (no. 3), a duet with a seraph that resembles a love duet.

An earlier version of the libretto includes stage directions, 11 some of which Beethoven vividly rendered into music: for example, the last measures of no. 3 realize the indication “Christ falls down on his knees.” The publishers removed these indications and wanted the libretto to have a more abstract, less human disposition, but Beethoven vehemently opposed this suggestion.

After the oratorio had been performed in Vienna at least three times, Beethoven revised it early in 1804, creating the version known to us today. The few preserved excerpts from the original version, 12 above all from the first aria, suggest that he was eager to dynamize and individualize formal processes, to achieve intensely vivid text setting (e.g. the unaccompanied vocal part in mm. 176 ff.), and to strengthen theatrical and dramatic elements (e.g. the powerful vocal cadenza at the end of the aria).

Church-music elements are only coloring in Christus : they appear only in conjunction with specific textual contexts, such as in the seraph’s recitative in no. 3: “So spricht Jehova,” mm. 7–13 (Grave, simple declamation in the vocal part, wind accompaniment stileantico whole and half notes, an embellished Renaissance-style cadence in mm. 12–13); there are, to be sure, also longer imitative passages, as well as a fugal final chorus on a grand scale (“Preiset ihn”) reminiscent of an oratorio chorus by Handel or Haydn.

It is the dramatic conception that makes Christus am Ölberge a central work in Beethoven’s gradual progress toward composing an opera. Alan Tyson and Sieghard Brandenburg, among others, have pointed out affinities with specific operas and have criticized the oratorio for its derivative stylistic diversity. Nevertheless, Beethoven also found individual solutions, as I want to illustrate by the scene-complex in nos. 4 and 5.

Immediately after Jesus has welcomed death (recitative, no. 4), for he will die to save humankind, the mercenaries who seek him are heard in the distance (“Alla Marcia”). 13 Jesus reacts in a recitative (“Those who have come to catch me are approaching,” “Die mich zu fangen ausgezogen sind, sie nahen nun”). Here Beethoven expresses what Jesus thinks and says, while the soldiers look for him, without departing from the standard sequence recitative–aria (see the use of the dotted search-motive for the soldiers, and the motivic connection of Jesus’s words to the recitative in no. 4). By musically tying together two simultaneous but spatially separated events (the soldiers’ search and Jesus talking), Beethoven creates the illusion of a three-dimensional stage-setting.

This effect becomes even stronger when, immediately after Jesus’s important words “Doch nicht mein Wille, nein! Dein Wille nur geschehe,” the march like search-motive returns and tension increases, culminating in the excitement (the A major chord, the dominant) at the beginning of the Allegro molto. With the soldiers’ sudden intrusion (“Hier ist er”), the music resolves into a unison, fortissimo D under a fermata – a harmonic and rhythmic analogy to the libretto’s dramatic action and rhythm of declamation. Jesus’s disciples awaken at the noise but, confused from drowsiness, ask themselves what will happen to them. That this dramatic conception had a powerful impact on contemporary audiences becomes clear in reviews of the performance: “The choruses of the soldiers, ‘Wir haben ihn gesehen, ’ etc. had the greatest effect. It was all the talk as the audience exited and for several days afterward. At the words ‘Hier ist er! Ergreift ihn! Bindet ihn!’ many felt so deeply affected that, according to their own statements, for a moment they feared for their own lives.” 14 Beethoven would go still further in this dramatic direction in Leonore .

Beethoven became caught in a critical crossfire because of these very qualities of scenic and dramatic immediacy in an oratorio. In one review of the score (published in 1811), a critic explained that in general an oratorio – as opposed to a drama, which portrays a “present-tense,” unexpected occurrence – represents an event “already known to us, but whose inner motivation, the accompanying feelings, are brought to life.” 15 Numbers 4 to 6, above all the trio, thus seemed too the atrical to this critic, while the role of Jesus’s disciples was “extremely common and trivial” in text and music. Also lacking was a “solid fugue,” according to this review, which seems to have a North German-Protestant aesthetic basis. In 1828, however, a critic for the Berliner allgemeine musikalische Zeitung distinguished between Beethoven’s “Catholic” oratorio and a “Protestant” oratorio by Louis Spohr: Catholicism tries to translate secrets and prophecies of the holy script into temporal terms, “to transplant them from the realm of inner reflection into that of sensual perception,” 16 making it inevitable that Beethoven’s music, too, should appear as “dramatically sensual perception” and show “Christ and the Angel ... as humans,” reminding us of “nothing higher.” However one chooses to evaluate the difficult questions of genre aesthetics raised by Christus am Ölberge, within Beethoven’s personal development as a dramatic composer it remains a crucial work in which the theme (which preoccupied Beethoven at this time) of the hero who overcomes fear and suffering emerges with particular distinctness.

Genesis, first performances, and publication

In the spring of 1807 Beethoven received a commission from Prince Nikolaus II Esterházy to compose a Mass for the name-day celebration of his wife, Princess Josepha Maria Hermengild. Since the Mass in C op. 86 is Beethoven’s first completed work for the divine service, it is understandable that he looked for orientation in other Masses, including the six late Masses by Joseph Haydn, also composed for Esterházy. Special emphasis should be placed on his reliance on Haydn’s Schöpfungsmesse Hob. HXII:13 because it is documented in the sketches for the first part of the Gloria. 17

Beethoven conducted the first performance of his Mass on 13 September 1807 with a large orchestra. Although there is evidence that the Mass was inadequately rehearsed, its unconventional music – in comparison with the familiar Masses by Haydn and Hummel – seems above all to have caused displeasure. To a countess friend Prince Nikolaus wrote: “Beethoven’s Mass is unbearably ridiculous and vile. I am not convinced that it could in honesty even be published. I am angry and ashamed about it.” 18

The Missa solemnis , too, had its origin in a specific occasion, the celebration of Archduke Rudolph’s enthronement as Archbishop of Olmütz on 9 March 1820, although this time Beethoven began composition without a commission. It was an act of personal feeling and esteem: it was to Rudolph, his patron, student, and friend, that he directed the words in the autograph above the Kyrie: “From the heart – may it go – to the heart!” 19 But he took so long on the work that the Mass could not be performed for the ceremony – only the Kyrie and parts of the Gloria were ready by then – and, interrupted by work on the Piano Sonatas opp. 109, 110, and 111, was not completed until the end of 1822. 20

Both masses occupy a position between liturgical music and religious music for the concert hall. Beethoven performed excerpts from the C major Mass in his famous concert of 22 December 1808 and permitted Breitkopf & Härtel to publish it with a German translation of the text (for use in concert performance) under the Latin. The Missa solemnis went far beyond the liturgically justifiable range of expression (Beethoven characterized it to various publishers as his “greatest” work and wanted to sell it for a higher price than the Ninth Symphony 21 ), and, in the event, the premiere did take place in a concert hall (7 April 1824, St. Petersburg), as did the first Viennese (partial) performance on 7 May 1824.

Music and text in the Mass in C and the Missa solemnis The Kyries: humankind and transcendence

“The general character of the Kyrie ... is heartfelt devotion, from which [comes] the warmth of religious feeling, ‘Gott erbarme dich unser, ’ without therefore being sad. Gentleness is the fundamental characteristic.... despite ‘eleison erbarme dich unser’ – cheerfulness pervades the whole. The Catholic enters church on Sunday in his best clothes and in a joyful and festive mood. The Kyrie eleison in the same way introduces the entire work.” 22 Beethoven thus described the Kyrie of his C major Mass on 16 January 1811 and in so doing defended himself against the underlaying of a German text, in which concepts like “the Almighty,” among others, are found. While many earlier mass-settings present powerful praise of both God and aristocratic authority, Beethoven proceeds from “the warmth of religious feeling,” “gentleness,” and “joyfulness.” For him the focus lies neither on God nor on princes, but rather on the human being entering the church, in whom emotions should be stirred and devotion awakened. 23

For this reason, probably, the bass section alone begins the Kyrie, intoning a single pitch(Example 13.2 ). Unaccompanied by the brilliance of instruments, the voice of the pleading people opens the Mass and, after the entrance of the other choral voices and strings in m. 2, will continue to lead the instrumental voices in the entire movement. Trumpets and timpani, typically ceremonial instruments, are silent throughout the Kyrie.

Example 13.2 Mass in C, Kyrie, mm.1–11

From this rhythmicized single tone, the tonal space (a stepwise rising line in parallel thirds against the pedal point on c), harmony, and dynamics slowly unfold up to m. 9, which touches on a surprising E major chord but immediately afterwards cadences in C major (mm.10f. and 14f.). The first Kyrie (mm.1–36) is permeated by the opening Kyrie intonation and the stepwise rising line, often in thirds; the C major to E major chord progression becomes the tonal scaffolding for the entire movement (Kyrie in C major, Christe in E major, Kyrie in C major).

C major and E major are also the keys of the two themes in the opening movement of the “Waldstein” Sonata op. 53 (Example 13.3a and b ): the first, like the Kyrie theme, beginning with a single tone, rising from the depths, animated – departure; the second, like the Christe theme, static, high-pitched, chordal, cadencing – goal (mm.35 ff.). The modulation from E major back to C major proceeds in precisely the same quick and surprising manner 24 in both the sonata and the mass movement (Example 13.3c : compare mm. 82f. and 84f. in op. 53 with mm. 76f. and 78f. in op. 85). However, parallels between the first Kyrie and Christe and the exposition of a sonata-form movement break down at the latest in mm. 84 ff.: instead of the unchanged repetition of the exposition or the beginning of the development the slightly varied Kyrie returns. Since in a mass – as opposed to a sonata – a recapitulation of the second thematic area (Christe) is hardly possible and harmonic closure cannot be achieved in this way (the modulation to E major is omitted and replaced by a brief cadence in C major, mm. 109–12), Beethoven integrates the unusual E major region by frequently juxtaposing C major and E major during the course of the movement.

Example 13.3

(a) Sonata op. 53, “Waldstein” first mvt., mm. 1–4 (beginning of first theme); mm. 34–38 (beginning of second theme in m. 35)

( b) Mass in C, Kyrie, mm.36–40 (Christe theme)

( c) op. 53, first mvt., mm.82–85 and op. 86, Kyrie, mm.76–79

The ABA′ formarising from the tripartite structure of the text presents the challenge of organically connecting the individual sections. In addition to the web of motivic and harmonic connections stemming from the very beginning of the movement, there are other significant integrating features: (1) continuous motion (uninterrupted eighth notes) pervades the Kyrie and Christe in a similar manner (one exception: the a cappella Christe statement in mm. 37–40) and only gradually subsides in the final measures; (2) the Christe eleison melody can be understood as inverting the rising line of the Kyrie; (3) the boundaries between the second (Christe) and third (Kyrie) formal sections are strikingly blurred: at the end of the Christe eleison text (m.68) the Kyrie motive enters – at first set instrumentally, then also vocally, in each case only the antecedent phrase followed by fragmentation – but still in the E major of the middle section; the tonal return does not take place until m. 84.

In the literature on the C major Mass it has not been recognized that Beethoven drew on several aspects of the first movement of the “Pastorale” Sonata op. 28. Its form also develops organically from the opening phrase and avoids conspicuous contrasts; closely related to the beginning of the Kyrie is the opposition of a low pedal point that first appears all by itself and the melodic line (in this case, descending). As in the transition to the third formal section of the Kyrie, Beethoven divides the thematic and harmonic articulation of the form in the sonata movement in order to blur the boundary of the second theme and support the sense of organic flow. Contributing to this quality in the sonata – as in the Kyrie – is the continuous pulse (quarter notes), which is interrupted only in a few formally significant places. The sonata and the Kyrie both depart from the usual texture of melody-with-accompaniment in their almost continuous four-part writing (the apparent accompanimental eighth notes in the Kyrie also have their basis in the chordally conceived melodic style), 25 and in both movements fragments from the first theme dominate the thematic-motivic work (compare the development and coda of the sonata with the end of the second formal section, mm. 68–78, and coda, mm. 113 ff., in the Kyrie: in each case fragmentation leads to inactivity without dramatic confrontation).

The parallels between the opening movements of earlier piano sonatas and the Mass demonstrate the latter’s close connections to Beethoven’s instrumental music. Nevertheless, he avoided simply transferring the formal schemata of instrumental music to Mass movements, as Mozart and Haydn often did; instead he applied instrumental techniques – linkage; contrasts; harmonic, thematic, and motivic processes – to tie together the distinct parts of the text-generated form. It is not surprising that there should be similarities to precisely that piano sonata (op. 28) in which Beethoven sought to minimize drama and contrast in the first movement of a sonata. With these qualities he succeeded in “irresistibly” awakening in the listener an “edifying” feeling, “through which the heart is led to devotion in the Kyrie .” 26

In 1824, Beethoven voiced similar sentiments about the Missa solemnis :

my primary goal in composing this grand Mass was to awaken and permanently instill religious feelings in both the singers and listeners. 27

Indeed the character of the Kyrie in the Missa solemnis , marked “Assai sostenuto. Mit Andacht,” is similar to that in the C major Mass. The relationship is manifest in the thematic material (gradual unfolding in parallel thirds between the bass parts and first violins in mm. 6–12, between clarinets and bassoons against the tonic pedal in mm. 23 ff. , 27ff. , 31ff.– the feeling of devotion slowly mounts; see Example 13.4 ), in the formal structure (motivic connections within and between the three text-generated parts, no dramatization of the return to the A section, even more changes in the second Kyrie – to round off the form – than in that of the C major Mass), and in the foreshadowing in the opening phrase of the tonal plan of the movement (B minor, the key of the Christe, is introduced as a chord in mm. 3 and 18). In the C major Mass considerable harmonic tension between sections offsets motivic and expressive evenness; in the Missa solemnis a less tense harmonic scaffolding opposes a large diversity of motives: in each case Beethoven was concerned to balance one parameter with the contrary tendency in the other.

The two settings differ decisively, despite the various connections. Although the Kyrie is the shortest movement of the Missa solemnis , it is in many respects more grandly conceived than the Kyrie of the C major Mass. 28 The thematic material does not develop from one scarcely audible low pitch; rather, the tonic supports a powerful, dotted tutti chord undoubtedly meant to be heard as a musical sign for God. 29 The emphasis is not on illustrating the immaterial, but rather on creating a musical analogy to the realization that for a human being the greatness of God remains intangible and unimaginable by desensualizing sound (see the unusual entrance “before the beat”). 30 Therefore the divine is consistently set against the human (see above all the varied repetition of the introduction with the vocal parts from m. 21 [see Example 13.4 .]: after the grand Kyrie statements [mm.21 ff. , 25ff. , 29ff.] comes the individual human reaction in the solo voice [mm.23 ff. , 27ff. , 31ff.] with calm linear progressions in the winds). This is a programmatic exposition of that which will remain the underlying idea of the Missa solemnis : the impact of the almighty divinity on individuals who can only vaguely perceive his unattainable greatness. Such unmediated juxtaposition of the irreconcilable domains of God and humankind plays a central role in the organization of the Gloria and Credo. 31 In both movements, Beethoven’s concern for the meaning of the text (he sought an adequate musical expression for every sentence or even single words) 32 results in block-like musical sections that butt up against each other abruptly.

Example 13.4 Missa solemnis , Kyrie, mm.21–33

Archaisms: “Et incarnatus est”

Well-established topoi – such as the beginning of the Kyrie – and archaic sonorities help shape the aural impression of the Missa solemnis . Yet Beethoven, who before and during the composition of the Mass had been studying early music (e.g. Palestrina), did not simply adopt these traditions: he chose them consciously, from a distance, as an alternative to the language of the Classical style. Among these idioms – a dimension scarcely discernible in the C major Mass – are such harmonic characteristics as the frequent use of the fourth scale degree (associated with plagal cadences and the ambivalent relationship between the chords on the fourth and first scale degrees, which in the Missa solemnis can be heard sometimes not only as subdominant and tonic but rather also as tonic and dominant), and the avoidance of the leading tone, especially audible in the “Et resurrexit” (Credo, mm. 188–93), along with prose-like declamation and rhythmic irregularities that work against the sense of well-defined meter.

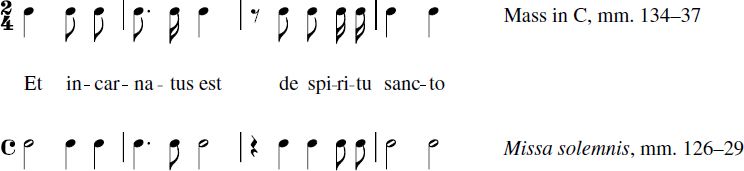

Beethoven used historical styles not only as “a leaven of modernity,” 33 but also semantically, as in the “Et incarnatus est.” The setting in the C major Mass resembles the section in the Missa solemnis in its identical speech-determined rhythm (Example 13.5 ) and in the distinct designs of the sections “Et incarnatus est” (homogeneous, in the Missa solemnis with gradually expanding orchestration) and “et homo factus est” (dialogue between an individual voice and a group, distribution of melodic material among various parts). Yet Beethoven sets the sections in the Missa solemnis more clearly in relief against each other and, above all, interprets their textual meaning more powerfully through musical analogies. He transfers the inconceivable secret of “Et incarnatus est” into mysterious, foreign music-historical worlds: 34 that of accompanied plainsong (single voice, Dorian mode, but, nevertheless, accompanied and with text-setting based on modern principles of metrical accentuation), that of vocal polyphony (mm.132 ff., but with a nimbus-like pulsation in some of the woodwinds and a flute symbolic of the Holy Ghost in its “disembodied” detachment from the beat), that of liturgical recitation (mm.141 ff., falso bordone ), which in its remoteness from meaningful articulated speech conveys that the true sense of “Et incarnatus” remains inconceivable for human beings. 35 The “historical” is thus used semantically: to express what cannot be understood rationally, the sacredly distant, placed in opposition to the familiar style of the “Et homo factus” (return of functional harmony; the melody is suggestive of a consequent phrase thus forming a musical analogy for arrival) .

Example 13.5 Declamation of “Et incarnatus est” in the Credo of both Masses

Agnus Dei

From a musical – not a liturgical – point of view, the Agnus Dei, the last part of the Ordinary, presents the problem of bringing the entire work to a persuasive conclusion. To round off the C major Mass cyclically, Beethoven refers in the final seventeen measures to the music from the beginning of the Kyrie (an independent recasting of the “Dona ut Kyrie” convention of using the music from the Kyrie for the “Dona nobis pacem” section of the Agnus); the close of the Agnus in the Missa solemnis is connected motivically with the “germinal motive” that permeates the entire Mass (e.g.Kyrie, mm.4–7). 36 Harmonic tension from the Kyrie is reintroduced and resolved in the Agnus of both masses. In the “Dona nobis pacem” of the Mass in C, C major and E major are brought together several times in cadential progressions; the Agnus Dei of the Missa solemnis begins in B minor, the “black” key of the Christe, and “opens” to D major only in the “Dona nobis pacem” .

The “Dona nobis pacem” is traditionally set to different, usually more serene music than the repeated “Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis.” Beethoven follows this custom, although in neither Agnus is he satisfied with a simple sequence of two parts: in the C major Mass – apparently for the first time in the history of Mass-settings – the somber C minor sphere of the Agnus reappears in the “Dona nobis pacem” (mm. 65–82). This is not done only to make the form more coherent; it also has a psychological interpretative function: peace cannot be established immediately and unconditionally; there must be another fearful appeal to the Lamb of God. The unexpected recall of the Agnus Dei music within the “Dona” section resembles an important aspect of the latter movements of the Fifth Symphony: the C minor sphere of the open-ended scherzo returns (mm.152–205) within the radiant C major of the finale; 37 there are also parallels to Christus am Ölberge in the idea of “overcoming” and the key-scheme C minor–C major.

In the Agnus of the Missa solemnis , the text “Agnus Dei ... miser ere nobis” also returns in the “Dona nobis pacem,” but now it appears within several, in part purely instrumental, contrasting sections, in which Beethoven expresses musically the kind of “peace” he had in mind: the unusual “war episodes” (mm.164–89, 326–53; war music as in a battaglia , operatic accompanied recitative to illustrate fear) represent the threat to “outward peace.” 38 In the war episodes foreign material in an alien key enters – so to speak, “from outside.” In the representation of the threat to “inner peace” (mm.266–326), which is a completely new idea in the history of the Mass, well-known material from earlier in the movement reappears in such a form that the music seems to come apart as an analogy for disturbed inner peace (cf. Example 13.6 ): 39 The lower theme is derived from the “pacem” motive (cf. choral soprano, mm. 107 ff.), but several pitches are deleted, it includes ties across the bar, and stands in opposition to the meter. The upper theme is related to the counterpoint to the “pacem” motive (cf. choral bass, mm. 107 ff.), but it is now disjunct, interrupted by many rests – it is no longer peaceful. After the first entry the two fugato themes both shift in different directions by a fourth (interval between entries now a seventh); they thus clash and the entire passage is harmonically unstable. The question of what exactly Beethoven wanted to depict here has until now remained unclear, though “inner peace” was extraordinarily common in his time as a theological image, which suggests that it was not Beethoven’s own subjective invention. In his work Ueber den innern Frieden , 40 widely read around 1800 and possibly also known to Beethoven (at least in its content), Ambrosius von Lombez described inner peace as the (positive) impact of God upon the individual. 41 When absent, “impatient ardor,” “conflicting impulses,” and “turmoil” prevail in the human heart (cf.Beethoven’s music in mm. 266ff.). 42 Each individual possesses the potential for inner peace in himself, but it can be activated only by God – a non-abstract God whose acts directly and personally affect mankind. 43 Beethoven’s vivid setting of the prayer for inner (religious) and outer (secular) peace in the Agnus, which far transcends the usual limits of liturgical settings, reveals how convincingly Beethoven was able to interpret the content of the Mass text in his music. 44 By May 1819 at the latest, he had become acquainted with various writings by the theologian Johann Michael Sailer, to whom he wanted to send his nephew for instruction. In conceiving and completing the Missa solemnis , especially the “Et incarnatus” and “Dona nobis pacem,” Beethoven had expressed in music in exemplary fashion Sailer’s appeal that believers should not simply parrot the prayers from the liturgy, but rather try to penetrate intellectually their spiritual meaning. 45 The profound interpretative dimension is, as required by Sailer, balanced by the stirring of warm human feeling (Sailer’s “religion of the heart”).

Example 13.6 Missa solemnis , Agnus Dei, mm.266–72

Theodor Adorno once posed the question: “Is the aesthetic problem of the Missa [solemnis] its reduction to the universal-human?” 46 In my view this is the aesthetic problem in all of Beethoven’s religious works before the Missa solemnis . After Beethoven had concerned himself with the human dimension of faith in Christus am Ölberg and the C major Mass, he succeeded in the Missa solemnis in finding the appropriate expression of the incomprehensibility of the divine and its effect on humankind. The human being still stands in the center – even in the Missa solemnis – but apprehends transcendence and its effects.

For Adorno the Missa solemnis was a problematic work, and this kept him from finishing a planned monograph on Beethoven. Although this “alienated masterpiece” is not infrequently performed, in his view it is usually received with paralyzed admiration rather than analytical acuteness. As Adorno correctly recognized, one can scarcely penetrate the aesthetic essence of the Missa solemnis through the perspective of middle-period procedures (e.g. thematic work): the Missa solemnis breaks the musical and expressive boundaries of everything that came before it. To describe how it differs from the works of the middle period requires emphasizing its similarities to other late works (among them the “Hammerklavier” Sonata, the Ninth Symphony, the late piano sonatas and string quartets) with respect to formal design, harmonic configuration, instrumentation, symphonic dimensions, effects of contrast, thematic organization, contrapuntal techniques, fugues, connections between individual movements, and much more. In recent years several far-reaching studies on these aspects, above all those by William Drabkin and William Kinderman, have appeared in English. 47 Here I have tried to suggest another possible approach, namely to present Beethoven’s ideas about religion and expression, and their compositional realization in the Missa solemnis in the context of his earlier sacred and liturgical works.

The entire repertory of Beethoven’s religious music had a very mixed reception because of the shift in evaluative criteria, especially for religious music, at the beginning of the nineteenth century, which made Beethoven, his listeners, and his critics walk a “tightrope” with no certain outcome. “Functional” music and genre traditions increasingly lost their aesthetic value; they could not survive the requirement that compositions be “original,” “individual,” “products of.” In each of his sacred and liturgical works (songs, oratorio, and Masses) Beethoven expanded existing norms, just as he did (and is recognized for having done) in the instrumental genres. In so doing he created in the masses true and great “works of art.”

Translated by Margaret Notley