ALAIN FROGLEY

The history of performing Beethoven is in essence the history of our entire Western culture of musical performance as it has evolved since the end of the eighteenth century. One is even tempted to write “Western culture” tout court . The ways in which we have kept alive the creations of one of the most potent icons of our civilization, the written instructions of the printed scores mediated by individual performers and by changing performance conventions, speak eloquently of deeper issues – of cultural value, tradition, authority, the individual and society, written versus oral communication, intuition versus reason. At a more concrete level, Beethoven’s music underpinned the formation both of the fundamental performance institutions of modern musical life, including the character and makeup of our public concerts and recitals, and of the very idea of a mass culture of “serious” music that elevates edification over mere entertainment. And from Franz Liszt’s use of selected sonatas in the nascent modern piano recital, through to the adoption of Beethoven by the “authentic” performance movement in the 1980s, Beethoven’s music has assumed a variety of contrasting symbolic meanings – Romantic rebel, disciplined Classicist, proto-Modernist – all of them heavy with prestige and authority, whether covertly or openly invoked. The attempt to project these meanings has shaped specific decisions about performance practice – the size of performing forces, details of tempo and articulation, the structure of concert programs – and these in turn have influenced the changing images of Beethoven’s art.

This history has been paradoxical as well as complex. Beethoven’s music has played the dominant role in the careers of some of the most celebrated performers and conductors of the last century-and-a-half, many of them composers in their own right: Liszt, Wagner, Bülow, Mahler, Toscanini, Furtwängler, Schnabel, to name just a few. While his music has been held in awe as the visionary outpouring of an individualistic genius, its fortunes have nevertheless depended on charismatic performers whose personalities have often come close to eclipsing – or at least subsuming – that of the composer in the eyes of the public; and while all have sought to be faithful conveyors of Beethoven’s intentions, differing views as to how these intentions can be divined have led to interpretations so divergent as to throw into grave doubt the whole notion of the musical work as a stable entity. If the slow movement of the Ninth Symphony takes just over eleven minutes in Roger Norrington’s version, and close to twenty in Wilhelm Furtwängler’s, in what sense are we still dealing with the same piece? In this context, formulations such as “Furtwängler’s Beethoven” become more than verbal conveniences. While such questions are hardly restricted to this composer, they strike one here with unusual force: can the music of Beethoven, undisputed master of form, timing, and compositional control at every level, really be this malleable if responsibly performed?

Such issues have been given fresh relevance in the past decade or so in the heated debate surrounding the adoption of Beethoven’s music by the so-called historical performance movement. 1 In addition, this has coincided with a surge of interest in studying performance as an historical topic in its own right, with important implications for analysis and criticism, rather than merely as a source of “authentic” performance practices, for which anything after the composer’s lifetime is normally disregarded. 2 In the light of such concerns, I intend here to sketch the rich history of performing Beethoven in terms of a few pivotal issues that focus shifting images of the composer, and the place of his music in broader performance culture. There will be no attempt to offer a “how-to” primer in performance practice, although topics relevant to such questions will inevitably be touched upon. And I shall start with Beethoven himself, who in his struggles to realize in practical terms the sounds of his imagination was frequently the first “interpreter” of his music. 3

Essays of this kind typically begin with a commitment to seek out the composer’s own intentions for performances of his or her music, and at one level the desirability of such a goal seems obvious. Y et it is fraught with problems, and even if we set aside the broader controversy surrounding “intention” in works of art, and its role in performing music, Beethoven presents an unusually difficult case.

This is not for a lack potential evidence. In addition to the indications found in the scores themselves, there is a wealth of material to be culled from the composer’s letters, conversation books, and the accounts of contemporaries. All Beethoven’s major works were performed during his lifetime, and in most cases with his direct involvement, either as pianist or conductor (and sometimes both), or as a consultant at rehearsals. 4 Furthermore, since his death the bulk of his output has continued to be performed: there has never been a Beethoven “revival” or any need for one. This has ensured an unbroken lineage of performers descended from Beethoven, as it were, initially through those who knew and worked with him or, in a handful of cases, were actually taught by him. Of the latter, Carl Czerny was the most influential; he published detailed instructions on the performance of Beethoven’s piano works, 5 and also taught the young Liszt, among others: the succession that runs Czerny– Leschetizky 6 –Schnabel – and beyond – is a particularly impressive one.

In a living tradition, however, such pedigrees can be deceptive. In Beethoven’s case one cannot be confident that they preserved with any detailed fidelity the master’s own practices: even those closest to the composer and writing as early as the 1830s and 1840s frequently contradicted one another, and Czerny’s testimony is not always internally consistent; and, as with most historical witnesses, the memories of Beethoven’s associates were clearly colored by their own biases, particularly in relation to changing performance styles after the composer’s death. 7 But they are hardly to be blamed: even when we try to go directly to the horse’s mouth, as it were, many factors confuse the historical record. Not least among these, as we shall see presently, are the problematic example set by Beethoven’s own performances, inconsistencies within his documented remarks on performance issues (his attitude towards the metronome, for example), and the complicating issue of his deafness. 8 Much may be inferred, of course, from our broader knowledge of performance practice in Beethoven’s Vienna, but here several broader factors urge caution. While Beethoven went further than any previous composer in trying to fix every detail of his works in notation, he clearly assumed that this notation would be realized in terms of the prevailing performance practice of his day – at least he left no general instructions to the contrary. Yet he lived at a time when much of this was in flux, and in some areas, such as the execution of trills and the introduction of the metronome, moving closer to present-day practice; his music made technical and interpretative demands on performers that went well beyond contemporary conventions; he was dissatisfied with most performances of his music; and, as with so many aspects of his art, his attitudes to performance reflect a strong tension between the ideal and the actual. 9

Nevertheless, there are several areas in which we can be certain that Beethoven conceived his music in terms of sounds and practices strikingly different from those encountered in modern performances. 10 First and foremost, the instruments of his day produced a more sharply differentiated range of timbres than their modern equivalents, and, when in combination, more transparent textures; this holds true equally for the strong identities of instruments within the orchestra, and the vivid contrasts between different registers on the piano (there were moreover several distinctive varieties of piano in use, of which Beethoven was most fond of the especially touch-sensitive and clear-toned Viennese designs). In orchestral music clarity was further enhanced – at least judging from recent performances on period instruments – by an absence of continuous vibrato and extended legato phrasing, a more even balance in the numbers of strings and wind than is found in a modern orchestra, 11 and the use of a smaller number of players overall. That said, Viennese orchestras varied wildly in both size and competency, reflecting a heterogeneous assortment of social, financial, and acoustic conditions; Beethoven’s symphonies were performed during his lifetime by as few as thirty-five players and as many as ninety (although a figure somewhere in the middle was more typical), and amateur performers often played alongside professionals. 12

On a different front, when performing piano concertos and chamber music with piano Beethoven would have added ornamentation to the written-out keyboard part. He did not trust other pianists to embellish his music, however, even if they were pupils: in 1816 Czerny was sharply rebuked for adding notes in a performance of the Quintet for Piano and Winds op. 16. 13 Yet to the special case of concerto cadenzas he took a different attitude: even though he wrote out compositionally sophisticated cadenzas in manuscript, he made no attempt to publish these, leaving other pianists to improvise or compose their own. 14 This underlines the fact that for much of Beethoven’s career it is difficult to separate sharply performance and composition. Although during his first decade in Vienna he was known as much for piano playing as for composition, even as a virtuoso he was admired above all for his improvisations, where composer and performer came together; 15 likewise, improvisation played an important role in Beethoven’s compositional process, some works clearly existing as fluid scenarios for improvisation before they were fixed in notation. And even when performing notated music, by himself or others, Beethoven impressed listeners with the spontaneously passionate character of his playing. Yet it is precisely this emphasis on improvisation and unpredictability which limits the usefulness of Beethoven’s own playing as a specific guide to performing his music – except in implying an overall freedom that he never willingly licensed to others. 16 As a conductor, Beethoven was also famously volatile and unpredictable, whether directing from the keyboard or using a baton (he was one of the first to experiment with the latter method). 17 Some problems stemmed from the ad hoc character of many of the ensembles involved, and from a lack of adequate rehearsal time; nevertheless, the results were chaotic on occasion. 18 We might at this juncture be tempted to adapt on Beethoven’s behalf an old adage: “do as I write, not as I do.” But for all the unprecedented effort Beethoven put in to preparing his scores for publication, with sometimes multiple sets of proofs and lengthy letters to publishers (though he was not a good or enthusiastic proofreader), even his printed scores contain numerous ambiguities and inconsistencies in their performance indications. One senses here an inevitable clash between Beethoven the composer for posterity, trying to fix a work once and for all, and Beethoven the spontaneous performer, ever sensitive to the multiple possibilities inherent in his material.

Nowhere is this tension felt more strongly than in the domain of tempo, a subject which has generated more debate than any other issue of Beethovenian performance practice. Beethoven himself never doubted its critical importance for his music – Schindler reports that the composer’s first question about any performance at which he was not present was “How were the tempi?” 19 – and it runs like a cantus firmus throughout the history of performing his music: so many issues of character, expression, and structural articulation depend upon it. It may seem ironic that the music of a composer celebrated as a rhythmic innovator should be so bedeviled by ambiguity and controversy in this fundamental aspect of musical time. The psychology of tempo is always a complex matter, however; and, more specifically, Beethoven’s music once again participated in a process of transition, in this case from an eighteenth-century approach predicated on a small number of basic tempo indications – allegro, adagio, etc.– which by custom implied certain broadly standardized speeds, towards the much more finely differentiated and wider overall range of tempi typical of the nineteenth century. As time went on, Beethoven’s indications became increasingly complex in their qualification of basic terms: “unfettered genius,” as he once put it, could not be bound by a system in which “Allegro” meant much the same for every piece over which it appeared. 20

In the light of such concerns, it is perhaps no surprise that Beethoven welcomed the invention of the metronome in 1813, since this enabled composers for the first time to indicate tempo in precise and objective terms. Indeed, he became the first major composer to use metronome markings, which he supplied for all nine symphonies, the string quartets up to op. 95, the “Hammerklavier” Sonata, and a handful of minor works. 21 Yet far from settling tempo issues in the works concerned, these markings have generated much heated and complicated debate. Above all, the tempi indicated have seemed too fast to many musicians. 22 The controversy is sure to continue, but the consensus of modern scholarship, and the fruits of the historical performance movement, all suggest that Beethoven’s markings must be taken very seriously indeed, even if they are not always followed absolutely literally (the ´=138 marking for the first movement of the “Hammerklavier” still seems astonishing). It is clear that Beethoven viewed the metronome as his best chance of ensuring that performers would be able to understand and project in their playing the unique and often delicately poised physiognomies of his creations.

Nevertheless, Beethoven had profound reservations about the metronome, and still believed that finding exactly the right speed depended on more intuitive considerations: “feeling also has its tempo,” as he wrote alongside the metronome mark in the autograph of the song “Nord oder Süd.” 23 The insight of the performer is even more critical to a second, related issue, namely the modifying of an initial tempo with ritardandos, accelerandos, and passages of contrasting stable tempi not explicitly indicated by the composer. Once again, balancing the often conflicting evidence is a delicate process, but this much seems clear: while Beethoven felt that an appropriate initial tempo should remain throughout as a background benchmark, he also believed that tempo must be modified as a piece progresses, in order to highlight formal junctures, characterize different themes, and articulate expressive contrasts and structure in general. 24 How far should the tempo be modified? Even with the advent of the metronome Beethoven made no attempt to mark such fluctuations. No doubt they would have been prohibitively numerous, and the composer probably also felt that, having been guided towards the right initial tempo, sensitive performers should instinctively understand what was required by way of subsequent modifications; yet the implication is also that these modifications were to be subtle enough that assigning meaningfully contrasting metronome marks would run the risk of exaggeration and rigidity. In his later music he specified numerous localized ritardandi, but these do not answer questions about larger-scale modifications, and, in the end, we are still left very much in the dark. Such questions are particularly important in the late works, whose subtle subversions of conventional characterisitics and structures often depend on hair-trigger distinctions of timing; ironically, as Beethoven legislated more and more detail in his music, notation proved limited in conveying its true spirit, and it depended more than ever on a perceptive performer.

This reminds us that tempo cannot easily be divorced from other considerations: a tempo that makes sense on a piano of Beethoven’s own time, for instance, may seem quite inappropriate on a modern Steinway. Most important of all is the relationship of tempo to articulation and rhythmic style, to the whole area of musical punctuation. Many questions remain unresolved here, not least how far Beethoven’s copious articulation markings – much more detailed than those of his predecessors – relate to the actual mechanics of beginning and ending notes, or to more conceptual questions of structural definition; certainly some of his longer slurs are not practicable as truly continuous streams of sound. As a pianist, Beethoven was famous for his legato playing, his ability to generate a singing tone and sustain this across long phrases; yet contemporary descriptions inevitably reflect expectations of the relatively detached articulation typical of the late eighteenth century. What does seem clear is that despite the increased importance of legato effects, much of Beethoven’s music was still conceived in terms of keyboard fingerings, string bowings, and other practices that created on the whole a more sharply etched rhythmic profile than their modern equivalents, and a substantially wider repertoire of articulation types. And some modern scholars and performers have also argued that contemporary concepts of rhetoric and poetic declamation are essential to understanding Beethoven’s approach to rhythm, including tempo: here once again, controlled flexibility appears to be the guiding principle. 25

The genuine artist lives only for the work, which he understands as the composer understood it and which he now performs. He does not make his personality count in any way. All his thoughts and actions are directed towards bringing into being all the wonderful, enchanting pictures and impressions the composer sealed in his work with magical power. 26

After his death, Beethoven’s music went on to become the core of the canonic performance culture that emerged in the mid-nineteenth century: the “imaginary museum of musical works” which is still with us today. 27 This edifice was founded on the public concert; the symphony orchestra and its repertory formed the central structure, but even the traditionally more intimate media of chamber and solo piano music were now often transplanted to the larger forum: the museum thus had three wings, dominated respectively by Beethoven’s symphonies, string quartets, and piano sonatas. 28 Vital to the new institution were two closely related ideas: first, the concept of the musical work as a stable and unique art-object that transcended ephemeral performance events, and whose every detail was fixed by its composer; 29 second, the image of the composer as heroic genius, whose works could inspire and even edify a new bourgeois audience bent on self-improvement. But could the vision of genius be communicated by just any competent performer playing the score “as written” ? At first glance, E. T.A. Hoffmann’s words quoted above, which effectively define the position that came to be known as “Werktreue,” or “fidelity to the work,” might appear to support this view: if the performing artist is to be completely self-effacing, then transmitting strictly what the composer has written is surely the best (the only?) course. On closer examination, however, matters are not so simple: the performer must understand the work “as the composer understood it” ; and if its essential qualities have been sealed up with “magical power,” presumably nothing less is required to unlock them again – simply reading the notation is obviously quite inadequate. Clearly, the performer must be almost as remarkable an individual as the composer. And since Hoffmann’s remarks come in the context of an essay on Beethoven, the stakes are high indeed.

Hoffmann was one of the first writers to interpret Beethoven’s music in terms of Romanticism (his famous account of the Fifth Symphony appeared in 1810), stressing its daemonic, mysterious qualities, and its evocation of the infinite and the spiritual. This view was commonplace by the 1830s, and it inevitably tempted the more daring performers, now also being cast as Romantic heroes, to break up Hoffmann’s delicate alloy of inspired humility, and to go well beyond the composer’s text in order to “bring into being” the wonders sealed therein. A round 1830, for instance, Berlioz was present at a performance where Liszt added trills, tremolos, and “impassioned chords” to the first movement of the “Moonlight” Sonata; more radically, in 1835 Liszt performed the same sonata with the first movement arranged for orchestra alone. 31 He treated op. 26 with similar freedom, once playing the first movement on an organ, and another time combining it with the last movement of the “Moonlight.” 31 Yet Berlioz, whose own Romantic credentials are not to be dismissed lightly and who admired Liszt enormously, was horrified by such licenses; and this highlights the fact that even during the heyday of musical Romanticism, sharply divergent views existed as to the proper limits of “interpretation” in Beethoven’s music, and on the performance of his music in general. I gnaz Moscheles and Clara Wieck, the two other virtuosi who pioneered public performance of Beethoven sonatas in the 1830s, took a more sober and “faithful” approach than Liszt (although they sometimes played only selected movements from a sonata, a common practice at the time). 32 Indeed, Liszt himself later repented of his péchés de jeunesse , and even in his younger days he had on occasion adhered strictly to the score. In the latter part of his career he treated the text of Beethoven’s works with great respect on the whole, even down to the controversial metronome marks in the “Hammerklavier” Sonata. It was in this very work, however, that he also took the most significant liberties of his later Beethoven performances, improvising an introduction that gradually yielded up the first movement, adding octaves to some of the trills in the fugue, and possibly reversing the order of the middle movements. 33 Like the composer-performer Beethoven before him, Liszt was impetuously unpredictable, and if a piece inspired him enough, he could not always resist responding to it as co-creator as well as executor (as is evident from his transcriptions and concert paraphrases of music by many different composers, of course). What Beethoven would have thought of this treatment of his music is another matter. It is important, nevertheless, that liberties taken in the spirit of sincere Romanticism be distinguished from the more cynical or haphazard disfigurations – movements played out of order, partially cut, or omitted altogether, and changes in instrumentation and scoring for instance – that Beethoven’s music routinely suffered in concession to public taste or inadequate performing resources up to the middle of the nineteenth century. 34

That composers loomed large in debates about Beethoven performance should not surprise us (and not only because many of them earned a living as performers and critics). As well as underpinning an emerging “museum” culture, Beethoven was also central to live issues in the composition of new music, in particular what might be dubbed crudely the struggle between Classicism and Romanticism, objective form and subjective expression, or, to invoke a wider framework, Apollonian and Dionysian aesthetics. Janus-faced, his music embodied the polarities at issue both within individual pieces, and between different genres and periods within the oeuvre as a whole, particularly between the first and last style-periods.

Such tensions were articulated most clearly in the area of conducting, whose relative novelty encouraged many practitioners to put their methods and opinions into print. In the quarter-century after Beethoven’s death, his music accelerated the ongoing transition from orchestral direction by a keyboard player (the last vestige of Baroque continuo practice), alone or in tandem with the principal violinist, to the modern practice of a conductor with a baton (though there remained pockets of resistance beyond mid-century). The conductor now became the equal of a pianist or other solo performer, except that his “instrument” was the orchestra; indeed, he provided an individualistic and potentially heroic focus for the otherwise dispersed identity of a large – and ever larger – ensemble. 35 The period 1830–60 saw the emergence of two primary viewpoints concerning the proper role of the conductor; these have shaped the history of conducting, and of performance in general, right up to the present day, and, again, Beethoven’s music loomed large in their formation.

On one wing were Berlioz and Mendelssohn; they defined the approach we find perhaps most familiar today, which, in theory at least, treats the composer’s score as the ultimate authority in performance decisions. As Berlioz vividly put it:

the sun, in lighting up a picture, reveals its exact design and colour. It does not cause either trees or weeds to grow; or birds or serpents to appear, where the painter has not placed them. 36

Inevitably, this discouraged the use of tempo modifications that were not specifically marked in the score, as well as changes in orchestration, or any other additions to the text; less inevitably, it also came to be associated with rhythmic precision, tight ensemble, and clarity of execution in general, and favored tempi that, as well as being steady, were on the fast side. 37 On the other wing was Wagner. Whereas Mendelssohn and Berlioz saw their role in terms of reproducing or recreating the composer’s vision, Wagner viewed conducting as a creative act. Although he also preached fidelity to the composer’s intentions, and did not tamper lightly with the text, for him the score was nevertheless a contingent representation of a conception that lay some way behind or beyond it. Only from an intuitive, empathetic understanding of the idea, in particular its projection in the structural melodic backbone that Wagner called the melos , could a correct interpretation of the notation emerge. 38 The most important job of the conductor is to articulate the changing character of the melos , and for this, Wagner argued, tempo modifications are essential; composers do not generally mark these, because they must emerge naturally from a deep understanding of the music, and so tempo is the arena in which the conductor becomes a true co-creator. Wagner’s own conducting, not surprisingly, emphasized flexible tempi, including speeding up as well as slowing down, even though this exacerbated the already poor ensemble typical of many nineteenth-century orchestras. F or Wagner, Beethoven marks a watershed in the history of music and the role of the performer: whereas tempo flexibility is occasionally required in earlier music, in Beethoven it underpins his whole style, and, given his seminal influence on the next generation of composers, it thus becomes the norm for modern music. 39

The mystical aura of Wagner’s approach, and his emphasis on the flexible unfolding of a long melodic line, accord well with his own music, of course, and invite us to connect it with Beethoven’s – an association Wagner was always keen to encourage. Mendelssohn and Berlioz, especially the former, likewise highlight issues that reflect their own compositional concerns. Both schools claimed to bring out the composer’s intentions, but one adopted a more metaphysical view of this concept, and by implication a more important role for themselves as “interpreters” of works rather than mere performers. Mendelssohn’s performances were perhaps stiffer than Beethoven would have wished; Wagner, on the other hand, probably went further in tempo modification than Beethoven envisaged – but then one remembers reports of the composer’s own impulsive performances, and is left to wonder.

Another area of widely diverging practices was that of “retouching” Beethoven’s orchestration to accommodate changes in instrument construction and playing techniques, some of which, such as the more powerful sound of the strings, profoundly changed dynamic balance within the ensemble; also significant were the acoustical demands of new, larger performance spaces. Most musicians believed that some kind of modification was essential, especially in the elaborately scored and texturally complex Ninth Symphony, and such retouchings can be heard even on quite recent recordings.

40

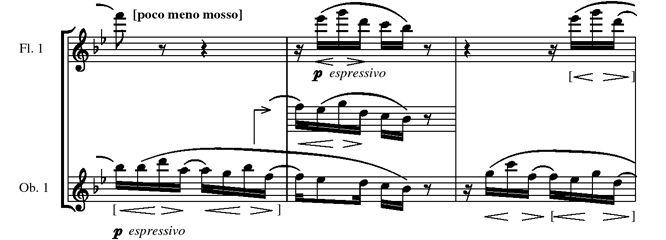

Wagner’s alterations in the Ninth range from relatively straightforward adjustments of balance, to more interventive changes which highlight his analytical understanding of the voice-leading, and thus constitute an element of “interpretation.” An example of the latter category is his re-writing of the flute and first oboe parts in mm. 138–43 of the first movement, designed to clarify what he believed to be the structural melodic line: this involves reshaping the oboe part at one point, transposing the flute down an octave at another, and adding new dynamic and tempo indications (see Example 15.1

; Wagner’s additions are shown in square brackets or on the middle stave).

41

Yet such tinkering appears timid beside Mahler’s audacious novelties, which included the use of timpani to hammer out the famous “Fate” motif in the Fifth Symphony, and the introduction of effects typical of Mahler’s own music, such as the shrill E![]() clarinet added to the score of the Eroica

, or the placing of wind-players offstage in the “Alla marcia” section from the finale of the Ninth

42

– surely a composer-performer trying to recast Beethoven in his own image. Nevertheless, even the specialist conductors that were emerging during this era – figures such as Willem Mengelberg and Bruno Walter – also took significant licences, although not generally as extreme as Mahler’s.

clarinet added to the score of the Eroica

, or the placing of wind-players offstage in the “Alla marcia” section from the finale of the Ninth

42

– surely a composer-performer trying to recast Beethoven in his own image. Nevertheless, even the specialist conductors that were emerging during this era – figures such as Willem Mengelberg and Bruno Walter – also took significant licences, although not generally as extreme as Mahler’s.

Example 15.1 Symphony no. 9 op. 125, mvt. 1, mm. 138–43 with Wagner’s retouchings

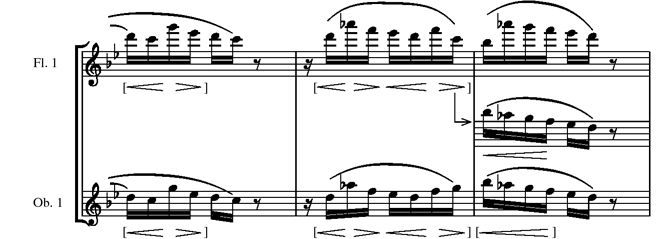

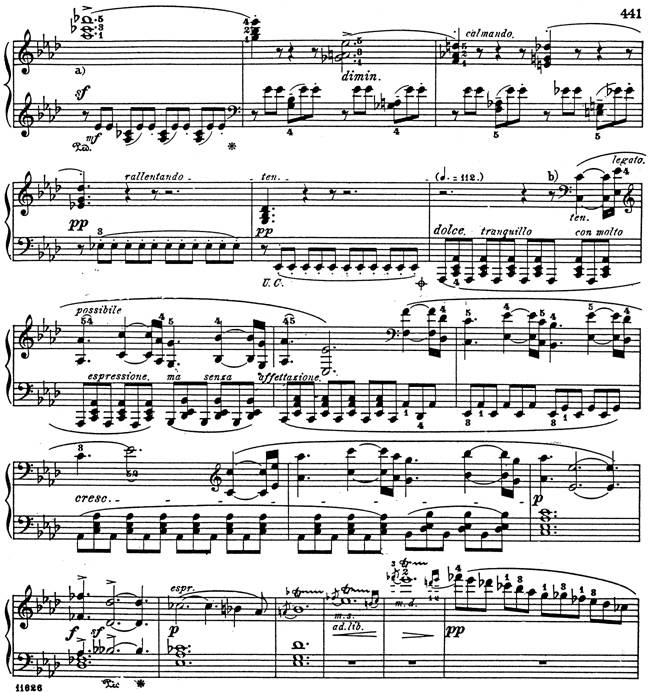

The period between c. 1870 and 1914 marked the height of a highly romanticized, Wagnerian school of Beethoven performance that touched all areas of his output, 43 and which although always controversial, gradually came to predominate; it was reinforced by, and helped reinforce, parallel trends in the critical and theoretical reception of the composer, and rising German nationalism was a powerful background presence. The era is epitomized by the influential figure of Hans von Bülow, who also draws together a number of threads pursued here. As pupil and son-in-law of Liszt, close (though later estranged 44 ) associate of Wagner, and in his multiple roles as pianist, conductor, and teacher, Bülow was heir to and transmitter of a powerful tradition. Something of the uncompromising loftiness of his view of Beethoven can be gleaned from the fact that he once played all five late piano sonatas on a single program, and on another occasion conducted the Ninth Symphony twice in one evening. 45 And he could make performance a medium for explicit historical-critical commentary: in playing any of the last five sonatas, he customarily improvised a prelude evoking an earlier sonata which in his view thematically adumbrated the later work. His edition of the piano sonatas, made in conjunction with Sigmund Lebert and Emmanuel Faisst, was widely used from its appearance in 1871 until well into the twentieth century. In recognition of Beethoven’s increasingly important role in piano pedagogy, a plethora of editions of the sonatas appeared during the nineteenth century; reflecting the priorities of the day, these recorded the interpretations of particular teachers and virtuosi rather than offering anything by way of textual criticism of existing scores. Bülow’s edition clearly embodies Liszt’s approach, to the extent that the master himself used it in his teaching late in life. 46 Not surprisingly, it is boldly interpretative, suggesting programmatic associations in many cases, and, more concretely, offering detailed suggestions for tempo modification. In the first movement of the “Appassionata” Sonata, for instance, a change from =.=126 to =.=112 is indicated at the second theme, with a resumption of the initial tempo at the closing theme (see Example 15.2 ; all the tempo markings and accents, the articulation of the left-hand part in the first five bars, and the slurring of the accompaniment to the theme are Bülow’s).

Example 15.2 Piano Sonata op. 57, mvt. 1, mm. 30–47 in edition by Hans von Bülow and Sigmund Lebert

By the end of the century a reaction began to set in against what some saw as the arbitrariness and undisciplined subjectivity of the Wagnerian approach, as a fetish for unconnected moments of cheap sensation, manufactured by exaggerated fluctuations of dynamic and tempo. Felix Weingartner, the most eloquent spokesman of the backlash, coined the dismissive term “tempo-rubato conductor,” and blamed Bülow for the phenomenon – perhaps unfairly. 47 But it was not until the emergence of Toscanini as a major Beethoven conductor in the mid-1920s, as conductor first of the New York Philharmonic and then of an orchestra created for him specially at NBC radio, that a decisive challenge was mounted to Wagnerian principles of interpretation. Toscanini’s hard-headed view that Beethoven’s scores must be followed to the letter if the composer’s true intentions were to be revealed – although he broke this rule more often than is sometimes suggested, particularly in the earlier part of his career 48 – is something that nowadays we may be inclined uncritically to take as a truism, but it cut right against the grain of the dominant performance practice of the time. A large number of “traditional” modifications to Beethoven’s scores in performance had become typical by the late nineteenth century, which, in addition to orchestrational retouchings of the kind discussed earlier, included certain customary rhetorical pauses and changes of tempo (the latter operating over and above the general flexibility of tempo that seems to have been the norm even up until World War II 49 ): all this Toscanini largely spurned.

His approach echoed in more extreme form Berlioz’s and Mendelssohn’s views of more than fifty years earlier; for a variety of reasons, however, the artistic and cultural climate now became unusually friendly to such ideas and their propagation. As Richard Taruskin has pointed out, 50 the widespread anti-Romanticism of the 1920s, typified by Stravinskian neo-Classicism and other modernist movements touting a new ‘objectivity’ in art, formed a harmonious backdrop for the brilliant clarity and at times remorseless rhythmic vigor of Toscanini’s conducting; the second wave of modernism that followed World War II finally elevated his approach into a new orthodoxy. And although he was a European, Toscanini’s willingness to challenge old orthodoxies – he was scathing on the subject of tradition – and his preference for American over European orchestras could not help winning him accolades in the New World. Other powerful factors were also at play, not least the populist impact of the new recording and broadcasting industries, and the related development of high-powered publicity for classical artists; in both these areas, Beethoven’s prestige was a valuable commodity.

The advent of recording had a powerful impact on many different aspects of musical life; for historians, it makes possible the study of actual performances, rather than merely writings about performance (early limitations on sound quality or modern editing techniques notwithstanding). 51 Recording and broadcasting came to play an important role in the media-fueled polarization and rivalry that developed between Toscanini and the other most celebrated Beethoven conductor of mid-century, a rivalry that brought to an unusually sharp point opposing philosophies born in the previous century. Wilhelm Furtwängler was the last great representative of the Wagnerian school of conducting, shaping his performances through almost continuous and often substantial tempo modification (tempi within the exposition of the Eroica symphony’s first movement, for instance, could fluctuate by almost twenty points on the metronome), 52 and emphasizing singing structural lines and darkly rich orchestral mass, often at the expense of unity and clarity of ensemble; indeed, he made his priorities clear when he commented that the great musical works were about “spiritual problems” that could not be brought out by literal adherence to the score. 53 Yet in Furtwängler’s case at least, such performances were not founded on passing whims of the moment: Nicholas Cook has argued convincingly that Furtwängler’s interpretations of Beethoven project sophisticated structural analyses, based on principles close to those of the theorist Heinrich Schenker, with whom the conductor had close contact. And Furtwängler, like Schenker, believed that in performing great works, there was essentially only one correct interpretation (allowing of course for some flexibility in detail). 54 But in any case, musical issues became fatally enmeshed with politics: Furtwängler’s decision to remain in Germany when the Nazis came to power, albeit as a sometime dissenting voice, was compared unfavorably to Toscanini’s staunch anti-Fascism and his abandonment of Italy for the United States. When war broke out, and as the radio “V for Victory” morse-code signal explicitly invoked Beethoven as a supra-national symbol of democratic freedom, any connection with what modern Germany had become was disastrous; Furtwängler’s reputation never completely recovered, even after the war, and with him a whole school of interpretation, already compromised obliquely by its Wagnerian ancestry, was tainted directly by its association with Nazism. Yet his recordings live on, as revelatory documents of a long and profound tradition that died with him.

In addition to preserving complete cycles of the symphonies under Toscanini and Furtwängler, the legacy of mid-century Beethoven recordings includes Artur Schnabel’s magisterial account of the complete piano sonatas, made in the early 1930s, and celebrated recordings by the Busch string quartet. Schnabel, while considerably less literal than Toscanini, advocated close adherence to Beethoven’s text; most controversially, this included following pedal markings that blur together harmonic progressions, and trying to honor the composer’s metronome marks in the “Hammerklavier,” which in the case of the notorious first-movement marking of ´=138 leads to near-disaster in his 1935 recording. 55

Despite such literal touches, however, there is a range of rhythmic nuance and compelling temporal flux in Schnabel’s playing – he indicated modest tempo modifications in his edition of the sonatas – that makes much post-1945 Beethoven performance seem either rigid or flaccid in comparison. Ironically, as the LP age recorded more and more Beethoven performances for posterity – in a survey compiled in the bicentenary year of 1970, High Fidelity listed no fewer than sixteen complete sets of the symphonies, twelve of the sonatas, and five of the quartets 56 – the range of different performance styles was becoming narrower and narrower, with artists taking few risks, and the majority following Toscanini rather than Furtwängler in their attitude to the text. Perhaps it was inevitable in this climate that notable exceptions to this rule, such as Leonard Bernstein and Glenn Gould, should veer towards the histrionic or the downright bizarre in an effort to escape the mold. 57

By far the most important development of recent years, however, and one which has shaken up hard the creeping homogeneity of Beethoven performance, has been the surge of “historically informed” performances using period instruments and techniques. This began as a trickle in the 1960s and 1970s, with pioneers such as Austrian pianist Paul Badura-Skoda and the German ensemble Collegium Aureum, but became a veritable flood in the 1980s, to the extent that at the time of writing half-a-dozen cycles of the symphonies played by period groups are now available on CD (there have been fewer recordings of the solo piano music and chamber works). Whatever the controversy surrounding the actual historical basis of such approaches, they have been wonderfully refreshing and thought-provoking. Beyond shedding light on general features of timbre and texture of the kind touched on above, period-instrument groups have gone further than ever before in trying to realize Beethoven’s metronome marks – even the most extreme – and thoroughly reconsidered many areas of rhythm and articulation. The results have often been startling. F or instance, in the recording of the Seventh Symphony by the Orchestre Revolutionnaire et Romantique under John Eliot Gardiner, the dominant rhythmic figure of the first movement, notated ![]() is articulated in a way that is almost impossible to notate but can be rendered approximately as

is articulated in a way that is almost impossible to notate but can be rendered approximately as ![]() combined with a fractional anticipation of the initial dotted eighth note as the figure is repeated, this creates an

agogic effect which imparts unprecedented energy to an already electrifying movement.

59

Whether or not there is anything “authentic” about this reading beyond its overdotting – it may in part have been suggested by early nineteenth-century bowings – to this listener at least it seems to offer something both genuinely new and which helps bring out more fully the intrinsic character of the movement. Such imaginative conceits have become more and more common in historically informed performances of Beethoven, countering their earlier tendency to fetishize context as well as text.

combined with a fractional anticipation of the initial dotted eighth note as the figure is repeated, this creates an

agogic effect which imparts unprecedented energy to an already electrifying movement.

59

Whether or not there is anything “authentic” about this reading beyond its overdotting – it may in part have been suggested by early nineteenth-century bowings – to this listener at least it seems to offer something both genuinely new and which helps bring out more fully the intrinsic character of the movement. Such imaginative conceits have become more and more common in historically informed performances of Beethoven, countering their earlier tendency to fetishize context as well as text.

A familiar subtext of the historical performance movement has been the battle over whether Beethoven is a Classical or a Romantic composer: if Furtwängler makes him the direct progenitor of Wagner, Gardiner forcefully reminds us that Beethoven studied with Haydn. And such radically new – and perhaps also old – approaches to Beethoven can once again be linked to broader developments in our society: analyzing the historical performance movement as a whole, Richard Taruskin has drawn attention to parallels with recent legal theory (a connection noted first by lawyers themselves), which has turned its attention increasingly to the unstable and political relationship between written texts and interpretative acts. 59 But whatever their origin, such developments – responsibly pursued – guarantee that Beethoven’s music will not be exhausted for us: they make us hear these well-worn pieces as if they were new again. Furthermore, plurality of performance styles ensures the life of our musical culture; a greater awareness of these styles and of their origins will surely encourage its continuing health. Whether we could ever revive, or should wish to revive, the interpretative world of Furtwängler is doubtful. On the other hand, it would be regrettable if the historical performance movement established a new orthodoxy that sharply limited the range of accepted approaches to performing Beethoven. Whether or not his music is really “better than it can ever be performed,” to use a striking phrase of Schnabel’s, the possibilities within it certainly cannot be exhausted by any one school or approach. And in any case, even if we do our best to follow his intentions, the ambiguous historical record leaves open a wide range of interpretative paths to follow. Which is surely a good thing – both for us and for Beethoven’s music.