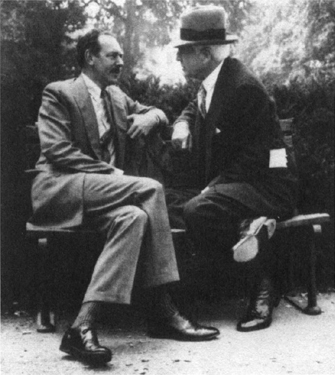

Acheson and Baruch in Lafayette Park

Diplomacy in an atomic age

The heavily laden B-29 Superfortress had been lumbering toward Japan for almost five hours when the voice of its captain, Colonel Paul Tibbets, came over the intercom. “We are carrying the world’s first atomic bomb,” he said. The copilot, Robert Lewis, gave a low whistle. Several crew members gasped. They had been briefed on the appalling power of the weapon they carried, but this was the first time that many on board had heard the word “atomic” used. It was just after 8 A.M. Japanese time on August 6, 1945, when Tibbets gave his orders: “Put on your goggles.”

And then there was light, a flash so bright that for a moment it suffused the plane. The tail gunner peered out. It looked like a “ring around some distant planet had detached itself and was coming up toward us,” he said into his recorder. “Target visually bombed with good results,” Tibbets radioed back to base. Copilot Lewis was far less restrained. “Look at that! Look at that!” he shouted, pounding Tibbets on the shoulders. “My God, look at that sonofabitch go!” But when he turned to his logbook to record what they had wrought, Lewis could think of nothing more original than the words gasped by the scientists at Alamogordo. “My God,” he wrote. “What have we done?”

At the Pentagon, there was a discussion about whether the press release announcing the attack should claim that Hiroshima had been completely destroyed. Robert Lovett, who as Assistant Secretary of War for Air was the civilian in charge of making the decision, counseled caution. He reminded the generals that they had more than once claimed the destruction of Berlin. “It becomes rather embarrassing after about the third time,” he noted dryly. What they wrote nevertheless quickly caught the attention of reporters. “It is an atomic bomb,” the statement said. “It is a harnessing of the basic power of the universe.”

In Rome, a general asked upon hearing the news, “Is this all it’s cracked up to be?” “Yes,” replied John McCloy, who was making an inspection tour on his way back from Potsdam. “It’s bigger than anything you’ve ever thought about.” In Washington that night, Dean Acheson wrote a letter to one of his daughters. “The news of the atomic bomb is the most frightening yet,” he said. “If we can’t work out some organization of great powers, we shall be gone geese for the fair.”

Slowly, as if feeling their way in a blinding light, people tried to understand what it all meant. As Stimson soberly proclaimed: “The world is changed and it is time for sober thought.”

“Yesterday another chapter in human history opened,” wrote Hanson Baldwin in The New York Times, “a chapter in which the weird, the strange, the horrible becomes the trite and the obvious.” In its next issue, Time magazine introduced a new section, “The Atomic Age.” A writer named James Agee was called upon to compile the cover story. He wrote:

In what they said and did, men were still, as in the aftershock of a great wound, bemused and only semi-articulate, whether they were soldiers or scientists, or great statesmen, or the simplest of men. But in the dark depths of their minds and hearts, huge forms moved and silently arrayed themselves: Titans, arranging out of the chaos an age in which victory was already only the shout of a child in the street. With the controlled splitting of the atom, humanity, already profoundly perplexed and disunified, was brought inescapably into a new age in which all thoughts and things were split—and far from controlled. . . .

The bomb rendered all decisions made so far, at Yalta and at Potsdam, mere trivial dams across tributary rivulets. When the bomb split open the universe and revealed the prospect of the infinitely extraordinary, it also revealed the oldest, simplest, commonest, most neglected and most important of facts: that each man is eternally and above all else responsible for his own soul. . .

The last great convulsion brought steam and electricity, and with them an age of confusion and mounting war. A dim folk memory had preserved the story of a greater advance: the winged hound of Zeus tearing from Prometheus’ liver the price of fire. Was the world ready for the new step forward? It was never ready. It was, in fact, still fumbling for the answers to the age of steam and electricity.

Man had been tossed into the vestibule of another millennium. It was wonderful to think of what the Atomic Age might be, if man was strong and honest. But at first it was a strange place, full of weird symbols and the smell of death.

On August 9, the day that America’s second and sole remaining atomic weapon was dropped on Nagasaki, Stalin summoned Harriman to the Kremlin. Events were moving quickly. Japan might surrender at any moment, and Stalin wanted to get his oar in before that happened. But the Chinese, under Harriman’s tutelage, had been dragging their feet in the talks with Soviet leaders since the end of the Potsdam Conference. Details had still not been worked out about the precise concessions Moscow thought it would get in China for joining the fighting.

The Soviets, unwilling to wait any longer, had declared war, Stalin told Harriman. Its troops at that moment were moving into Japanese-occupied Manchuria. This was not, of course, what Harriman wanted to hear, but he had to feign at least a semblance of happiness that the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. were once again allied against a common enemy.

Stalin also had another subject on his mind, but he was careful not to appear overly concerned about it. “He showed great interest in the atomic bomb,” Harriman reported, “and said that it could mean the end of war and aggression but that the secret would have to be well kept.” As Kathleen, still serving as her father’s hostess in Moscow, wrote to her sister: “Ave’s just returned with the news that Russia is at war with Japan. I wonder how many people will attribute it to the atomic bomb.”

When Japan offered to surrender the following night, Harriman was called back to the Kremlin by Molotov to discuss the proposed terms. The only concession the smoldering nation requested was the right to keep its emperor. The Soviets, Molotov said, were skeptical. Their troops were continuing their advance in Manchuria, and there was no reason to settle for less than complete capitulation.

After midnight, while the discussion was still under way, Kennan burst in with a message. Washington wanted to accept the Japanese surrender offer immediately, he exclaimed, and sought Moscow’s concurrence. When Molotov promised that his government would have a reply ready the following day, Harriman declared that would be too late. A decision must be reached before the night was over.

After two hours of waiting at Spaso House, Harriman was called back to the Kremlin for a predawn conference with Molotov. The Soviets would join in accepting the surrender. But the message he brought from Stalin had a second sentence. The Allies, it said, should jointly “reach an agreement” on which commander or commanders should control the occupation.

Harriman was incensed. Russia had been fighting for all of two days, he thought to himself, and there was no question that General MacArthur would be the Supreme Commander. Even if the Soviets would accept this choice, it was a decision in which they should have no say. Although he lacked any instructions from Washington, he knew what the response would, or should, be. “I reject it in the name of my government,” the ambassador solemnly decreed. After an hour, Molotov telephoned back to say that Stalin had agreed to withdraw the request for a joint say in who should command the occupation.

Years later, McCloy would praise Harriman for taking the matter in his own hands. It was a good thing he had decided to be firm without consulting Washington, McCloy confided, because the U.S. was so keen to see the war ended it would have accepted almost anything the Soviets requested. Harriman later recalled he had been adamant about rejecting the Soviet demand “because I knew that it would lead to the Russians having a major say in the future of Japan.”

When the final announcement of V-J Day reached Spaso House a few nights later, a raucous reception was under way for General Eisenhower. “After that,” wrote Kathleen, “we had a hard time getting rid of some of our drunker Soviet guests.”

“I took a great shine to Marshal Zhukov,” Kathleen added in describing the affair to her sister. Eisenhower’s visit had produced a massive outpouring of public affection, which impressed Harriman as genuine. When Eisenhower and Zhukov, the two great Allied commanders, were introduced at a soccer game, the cheers “surpassed anything I had ever heard,” Harriman reported. Eisenhower was a living symbol of Soviet-American cooperation, and Harriman sensed a fervent yearning, among the people if not their leaders, for it to continue.

The spirit infected Eisenhower, who assured Harriman that his friend Zhukov, who called him “Ike,” would succeed Stalin and usher in a new era of friendly relations. He and Zhukov had linked arms in repeated toasts to peace, Eisenhower explained. Alas, the ambassador argued, such hopes were “unrealistic.” Military leaders, Harriman had discovered, were the last to realize that the era of wartime cooperation was over. The greater the hopes, he knew, the greater would be the eventual disillusionment. “Like General Marshall,” he later wrote, “Eisenhower was slow to understand the crucial importance of the Communist Party in setting Soviet policy.”

On August 12, the very morning that Stimson arrived at the Ausable Club, he began phoning his assistant back in Washington to talk about atomic control. The doctors had ordered the old colonel to take an unbroken rest, so he had headed up to the private retreat in the Adirondacks where both he and McCloy owned summer cabins. Yet he could not take his mind off the bomb. Each day he would call McCloy to talk about it, to say he had been rethinking his views on the Soviets. Russia’s totalitarian system still repulsed him, Stimson admitted. But he had begun to agree with McCloy: working with the Kremlin to control atomic weapons must take precedence over any dreams of forcing that regime to liberalize its rigidly repressed society.

Finally, McCloy flew up to the Ausable Club to help write a recommendation for controlling the bomb. They both believed strongly that Washington should approach Moscow with an offer to share scientific knowledge as a first step. But the news that McCloy brought to the mountain bungalow was dispiriting. Byrnes was ready to leave for London to meet Molotov and other Allied Foreign Ministers at their first postwar conference and, McCloy lamented, “wished to have the implied threat of the bomb in his pocket.”

During the war, McCloy made a habit of working seven days a week, many times past midnight. Now he felt he deserved a vacation and hoped to spend some time in the Adirondacks fishing with his wife and son. But he found it hard to have a peaceful holiday. Ellen slipped on some rocks and badly wrenched her leg. Moreover, Stimson was anxious to finish their memo before Byrnes left for London. They polished it off during the week before Labor Day, but Stimson’s sense of urgency prevented McCloy from spending the long weekend with his family. He was dispatched back to Washington to explain the plan to Byrnes and inform him that Stimson planned to propose it directly to the President.

When he arrived in the Secretary of State’s office that Sunday morning, McCloy emphasized that the proposals for atomic control he had worked out with Stimson at the Ausable Club would not mean disclosing any technological procedures to the Soviets. But his worst fears about Byrnes were confirmed. The Secretary of State was still adamantly opposed to seeking any form of atomic cooperation. The Russians were “only sensitive to power,” Byrnes explained, and they were especially “cognizant of the power of this bomb.” McCloy noted in his diary: “With it in his hip pocket, he felt he was in a far better position to come back with tangible accomplishments.”

When Stimson got back from the Adirondacks that day, he cornered Byrnes in a White House corridor and discovered McCloy’s pessimism was justified. As Byrnes prepared to sail for his showdown with Molotov in London, carrying his nuclear bludgeon, a disheartened Stimson submitted his resignation. In reluctantly accepting it, Truman had one request: that the Secretary stay on for another two weeks so that he could present to the Cabinet his ideas on the postwar atomic age.

Over the next week, McCloy worked late into the nights fleshing out the Ausable Club paper into the first formal proposal for a Soviet-American atomic arms control “covenant.” For more than forty fruitless years, this quest would be pursued. The core of the recommendation, which Stimson signed and took to the White House on September 12, was that the U.S. should approach the Soviet Union with a plan “to control and limit the use of the atomic bomb.” Washington would pledge to “stop work” on atomic weapons and “impound what bombs we now have.” The offer ought to be made directly to the Soviets, not through the U.N. “Action of any international group of nations,” they wrote, “would not be taken seriously by the Soviets.”

The alternatives were ominous. “Unless the Soviets are voluntarily invited into the partnership,” they warned, “a secret armament race of a rather desperate character” would ensue. The bomb “virtually dominated” other diplomatic issues. “If we fail to approach them now and merely continue to negotiate with them, having this weapon rather ostentatiously on our hip, their suspicions and their distrust of our purposes and motives will increase.” A covenant for control, on the other hand, would be a “vitally important step in the history of the world.” And thus, the seeds of nuclear arms control were planted by McCloy and Stimson even before the race began.

The rationale behind this approach, and indeed its philosophic foundation, was contained in a sentence at the heart of the long memo. There, once again, Stimson quoted his favorite Bonesman maxim. “The chief lesson I have learned in a long life,” he said, “is that the only way you can make a man trustworthy is to trust him.”

After Stimson explained the paper paragraph by paragraph, the President wholeheartedly concurred. “We must take Russia into our confidence,” he said. Truman also raised this radical proposal at the next Cabinet luncheon, which was intended as an informal farewell for the departing Secretary, and announced that he would make it the sole topic on the agenda for the next Cabinet meeting. Would Stimson stay on for a few more days, Truman asked, to give the Cabinet one last benefit of his wisdom? “I will be there,” Stimson replied, “if I can walk on my own two feet.”

Friday, September 21, was a busy day at the Pentagon. It was Stimson’s seventy-eighth birthday, and wherever he went a song and a cake seemed to follow. It was also his last day in office, and his plane was at the airport waiting to make the last trip to Highhold. But most importantly, that Friday was the day of the special Cabinet meeting, the one that Truman had dedicated to a single topic, the aging warrior’s final and most critical crusade.

When the President called on him that afternoon, Stimson spoke eloquently and off the cuff. The only way to avoid a devastating arms race, he argued, was a direct offer to the Soviets to share control of the atomic bomb. The Russians had “traditionally been our friends,” he said, harking back to the Civil War and the sale of Alaska. There was no “secret” at stake, for the scientific principles were common knowledge. And once again he imparted his gentleman’s faith that trust was the way to beget trust.

As the discussion worked its way around the table, the Cabinet was split. Most forcefully opposing Stimson’s plan was Navy Secretary Forrestal, whose misgivings about spreading Bolshevism had steadily deepened. The Russians “are essentially Oriental in their thinking,” he stated. “It seems doubtful that we should endeavor to buy their understanding and sympathy. We tried that once with Hitler. There are no returns on appeasement.” The bomb, he insisted, “was genuinely the property of the American people.”

At the other extreme was Commerce Secretary Henry Wallace, the man Roosevelt had dumped as Vice-President and the most starry-eyed of those who still believed that Soviet-American friendship was possible. The question, as he put it, was whether the U.S. would “follow the line of bitterness” or “the line of peace.” The secrets of the atom were not exclusive U.S. property, and to try to withhold them from the Russians would make them “a sour and embittered people.” Forrestal, putting his usual alarmist spin on whatever he heard, in his diary accused Wallace of being “completely, everlastingly and wholeheartedly in favor of giving it to the Soviets.”*

Had Wallace been his only strong ally, Stimson may have retreated to Highhold with his hopes shattered. Instead, however, he found reassuring support from an important new quarter. With Byrnes away in London having a conspicuous lack of success achieving anything with a weapon he could not pull out of his hip pocket, the State Department chair at the Cabinet table was being filled by Dean Acheson.

Acheson, anxious to return to private life, had submitted his resignation as Assistant Secretary, and it had been accepted “with reluctance” by Truman and Byrnes back on August 9, the day the second bomb was dropped. He and Alice then took a train up to Saranac, New York, where their daughter Mary was recuperating from tuberculosis. Next on their agenda was a long-awaited jaunt with friends through the backwoods of Canada. After some warm embraces, Mary remembered to mention to her father that Secretary Byrnes had been trying all day to reach him on the phone.

It turned out that Byrnes and Truman, preoccupied by the bomb and the Japanese surrender, had not meant to accept the Assistant Secretary’s resignation after all. As Acheson explained to his confused friend Frankfurter: “The Hon. Jimmy brought me back to Washington by air and told me I had caught him in a weak moment and he didn’t mean any of it. I had not escaped, I was not to be allowed to and that the President would draft me by virtue of Title something Section something if I resisted.” Instead of his freedom, Acheson was offered a promotion to Under Secretary, replacing his fellow Grotonian Joseph Grew.

Acheson wavered at first. One of his worries was money. Now fifty-two years old, he had cultivated a gracious style and longed to become accustomed to the manner in which he was living. His Georgetown home had been expanded into a right-sized little mansion, and Harewood Farm had been renovated and decorated in a simple yet comfortable manner. The promotion would raise his salary only from nine thousand dollars a year to ten thousand dollars, a fraction of what he could make as a senior partner at Covington & Burling, his prosperous old law firm. Nor was he particularly fond of Byrnes.

On the other hand, he was acutely aware of history and the fact that he might play a role in it. The new job would put him at the very epicenter of power, a notion that no protégé of Peabody and Brandeis could easily resist, and give him a chance to be present at the creation of a whole new era.

At his wife’s suggestion, Acheson spent one night pretending he had accepted the job and the next night pretending he had rejected it. “The experiment did not help,” he reported. “Both assumptions depressed me.” But with the aid of Byrnes’s flattery, to which Acheson was quite susceptible, he finally decided to sign on. “I have no strength of character anyway,” he wrote Frankfurter, “and certainly not when anyone is as charming to me as His Honor was.”

Acheson was still considered, by himself and others, a traditional “liberal,” one of the Frankfurter-New Deal crowd that believed strongly in both America’s global role and the need for good relations with Russia. I. F. Stone wrote in Nation magazine that Acheson was “friendly to the Soviet Union” and represented “by far the best choice for Under Secretary.”

Yet even though Acheson still thought friendly relations with the Soviets were quite possible, he had begun to be swayed by his old friend Harriman’s constant refrain in State Department discussions and Georgetown dinners that friendliness must be mixed with firmness. Peabody’s Groton did not breed softness. Allowing itself to be pushed around, Acheson believed, was certainly no way for the U.S. to win the respect of the Soviets.

The pattern of his thinking was clear within his first few weeks on the job: although a leading advocate of working with the Soviets, he visibly bristled when Prague and Moscow demanded the removal of U.S. troops from Czechoslovakia. Washington must never flinch or retreat from a test of its resolve, he argued in stiffening Truman’s backbone. American military presence, said the new Under Secretary, was “the most concrete and telling evidence of our interest in the restoration of stable and democratic conditions.” The GIs would stay, Truman and his State Department subsequently decided, until a deal could be worked out for Soviet troops to withdraw simultaneously.

Acheson’s outlook was not primarily motivated by a belief in the wickedness of the Soviets, at least not yet. Mostly it was guided by his anti-isolationist instincts. In the postwar world, with Britain on the ropes, America would have to be the champion of order and the paladin of a new Pax Americana. Even before his confirmation, Acheson entered into a contest of will with Douglas MacArthur, who had suggested that demobilization could be hastened. While other officials prudently ignored the general, Acheson called a press conference to decry the growing “bring the boys home” mentality and to remind MacArthur that policy was made in Washington. Thus while most liberals regarded him with favor, Acheson found his nomination most vigorously challenged by the old America First gang, the former isolationists who applauded MacArthur’s unilateral approach to American interests in Asia and looked suspiciously at the European internationalists of the East Coast Establishment.

Acheson was very much a practical man, one who eschewed visionary schemes. The U.N. could play a useful role, he believed, but the hope that it could preserve peace among the Great Powers he treated with the same contempt that Brandeis heaped on “universal Plumb Plans.” Its charter, Acheson pronounced, “was impractical.” Peace could be maintained only by the Great Powers working in concert. That was why he thought there must be some modus vivendi with the Soviet Union.

This pragmatism was also one reason Acheson never saw much point in cloaking America’s overseas interests with idealistic phrases about democracy and self-determination. The U.S. had important strategic and economic interests in such places as Iran, Turkey, and Greece—hardly paragons of electoral enlightment—and these interests should not be obscured by what Acheson took to calling “messianic globaloney.” When faced with the “evangelical enthusiasm” of those who believed in world government and universal democracy—and who disparaged the need for power diplomacy—Acheson would cite the admonition of Andrew Jackson at the Battle of New Orleans: “Boys, elevate them guns a little lower.”

Yet there were traces of a new mellowness in Acheson’s personality. No less sure of himself, he nonetheless felt less need to assert his self-confidence. Partly this was a result of his job as Assistant Secretary, which involved dealing with Congress and placating the likes of Arthur Vandenberg. Perhaps even more important was his daughter’s prolonged recuperation from tuberculosis up at Saranac. He was deeply attached to Mary, who had served as a code breaker during the war and married Harvey Bundy’s son William. Every evening he would write her long chatty letters on everything from national policy to the foibles of his secretary. “Mary’s illness marked a tremendous crisis in Dean’s life,” a friend said. “He became reconciled to slow, hard answers to difficult questions.”

Shorn of some of its brashness, the force and elegance of Acheson’s intellect came through more vividly. Fuzzy abstractions annoyed him. Despite his reputation as a complex man, he approached problems actually quite simply. “His method,” Mary recalled in an interview years later, “was to sift through all the complications and find a way to solve a problem, not make it more complex. If the problem just could not be solved, he would recognize that and simply do the best he could.” He adopted the favorite sayings of two of his friends: Lovett’s “To hell with the cheese, let’s get out of this trap,” and Marshall’s “Don’t fight the problem, decide it.”

The new job as Under Secretary brought Acheson real power. Byrnes tended to ignore the department, handling some of the big problems on his own as a roving troubleshooter while delegating Acheson to make the day-to-day decisions at his nine-thirty staff meetings. For 350 out of his 562 days in office, Byrnes was out of town at foreign minister meetings or other excursions, leaving Acheson as Acting Secretary. In fact, Byrnes departed for the London Foreign Ministers’ Conference before Acheson was even confirmed.

And so it was that Acheson, having made a conscious decision to seek his place in history, was the Acting Secretary of State when Henry Stimson telephoned to lay the groundwork for the critical September 21 Cabinet meeting and to argue his case for making a direct offer to the Soviets to share control of the atom.

The topic was already familiar to Acheson; for almost a month he had been working with McCloy on legislation that would set up a new domestic atomic energy agency. Discussing the issue late into the evenings in the cozy study of Acheson’s Georgetown home, the two men had concluded that it was difficult to divorce domestic issues from international ones.

After hearing Stimson explain his proposal on the telephone, Acheson expressed some reluctance about breaking with Byrnes, who he knew opposed any approach to the Soviets. Yet the new Under Secretary deeply sympathized with Stimson’s perspective and asked to see his memo to Truman. “Acheson is evidently strongly on our side,” Stimson wrote in his diary that evening.

When Acheson’s turn to speak came at the Cabinet session on September 21, Stimson could not have written a better script himself. There was “no alternative,” Acheson said, to sharing atomic information with Russia. He could not “conceive of a world in which we were hoarders of military secrets from our Allies, particularly this great ally” whose cooperation was essential for “the future peace of the world.” The exchange must be done on a “quid pro quo” basis, but above all the Grand Alliance must be kept intact—especially when it came to atomic weapons.

The President, at the conclusion of the Cabinet meeting that Friday morning, requested memos on atomic control from Acheson and Robert Patterson, the former judge who had served with McCloy, Lovett, and Bundy in the War Department and was replacing Stimson as Secretary. Patterson’s product was a limp and fuzzy recap of Stimson’s ideas. Acheson, however, was determined to impress the President with the eloquence and elegance of his arguments. He did.

The theory behind atomic power was widely known, Acheson wrote, and it was futile to believe that it could be treated as a “secret.” Any attempt to exclude the Soviets would be seen as “evidence of an Anglo-American combination against them.” Moscow would soon have the ability to make its own bomb. “The advantage of being ahead in such a race,” he said, “is nothing compared with not having the race.”

Acheson conceded that tensions with the Soviets were increasing. “Yet I cannot see why the basic interests of the two nations should conflict.” His recommendations were similar to those Stimson and McCloy had made: The U.S. should make a direct approach to the Soviets—not through the U.N.—offering a step-by-step plan to share scientific information and adopt verifiable safeguards against the production of atomic weapons by any country. If cooperation fails, Acheson warned, “there will be no organized peace but only an armed truce.”

So impressed was Truman with the power of the Acheson-McCloy-Stimson position that he asked the Under Secretary to prepare a presidential message to Congress linking domestic and international control of atomic energy. With his assistant Herbert Marks, Acheson put together a statement that was sent to Congress on October 3. Using Stimson’s phrases about “a new force too revolutionary to consider in the framework of old ideas,” Acheson wrote a resounding clarion call for “the renunciation of the use and development of the atomic bomb” and for a system in which “cooperation might replace rivalry in the field of atomic power.”

Before the Soviets could be persuaded to accept such a program, however, it was necessary to persuade Congress. Leaders of both parties reacted skeptically, at best, to the President’s message. “I think we ought to keep the technical know-how to ourselves as much as possible,” said Senator Richard Russell, a conservative Georgia Democrat. The American monopoly should be retained, added Republican Arthur Vandenberg, until there was “absolute free and untrammeled right of intimate inspection all around the globe.” A poll of sixty-one congressmen showed that fifty-five opposed sharing knowledge of the bomb with any country. And 85 percent of the public, according to a National Opinion Research Center survey, wanted the U.S. to retain exclusive possession of the weapon as long as possible.

Among those who thought it folly to share control of atomic weaponry with the Russians was Kennan, once again temporarily in charge of the embassy while Harriman traveled through Europe. What particularly grieved him was that news of the proposals circulating in Washington came to him from a delegation of traveling congressmen. Their visit not only reminded the moody diplomat about how little Washington understood the Soviet Union, it also reinforced his disdain for politics and politicians.

Surprised that he was able to obtain an interview with Stalin for the delegation, Kennan nervously waited at their appointed rendezvous for the congressmen to finish their obligatory tour of the Moscow subway system. The visitors, however, were being treated to a lavish late-afternoon “tea,” with the usual abundance of vodka toasts, somewhere in the subterranean bowels of the city. Just before 6 P.M., the scheduled time of the interview, the well-lubricated group finally emerged.

As they tore off toward the Kremlin in two limousines, the members got a bit rowdy. “Who the hell is this guy Stalin anyway?” bellowed one of the drunker congressmen, who proceeded to threaten to jump out of the car. “You’ll do nothing of the sort,” Kennan sternly reprimanded. “What if I biff the old codger one in the nose?” came the drunken cry.

Kennan was mortified. “My heart froze,” he recalled. In the end, however, the interview came off relatively smoothly, although Kennan noted that the drunken member did “leer and wink once or twice at the bewildered dictator.”

For his part, Stalin was on his most charming behavior. When Senator Claude Pepper of Florida asked about Soviet intentions, the Generalissimo replied: “Our people are tired. They couldn’t be induced to make war on anybody anymore.” Afterwards, he pulled Kennan aside for a private word. “Tell your fellows not to worry about those Eastern European countries,” the Soviet dictator told the skeptical diplomat. “Our troops are going to get out of there and things will be all right.”

The visit of the unruly legislators, Kennan later wrote, was one of the many small episodes that “bred in me a deep skepticism about the absolute value of people-to-people contacts.” In addition, Kennan’s contempt for the intrusion of domestic politics into foreign policy jumped another notch. What bothered him most, however, was the information imparted by Senator Pepper, then a strong advocate of Soviet-American friendship, that plans were being considered for sharing with the Kremlin control of atomic weapons.

His message to Washington was among his most impassioned to date. “There is nothing—I repeat nothing—in the history of the Soviet regime,” Kennan proclaimed, “which could justify us in assuming that [Russian leaders] would hesitate for a moment to apply this power against us if by doing so they thought that they might materially improve their own power position in the world.” Proposals based on other assumptions “would constitute a frivolous neglect of the vital interests of our people.”

The world, Kennan had learned, was not run by Stimsonian gentlemen who lived according to social club codes of reciprocated trust. Certainly the Kremlin was not. So Kennan decided to suggest something that would help lay the groundwork for what would become the present-day Central Intelligence Agency: the establishment of a new espionage apparatus to spy on the Soviets’ atomic facilities.

Appended to Kennan’s missive about the folly of sharing atomic secrets was a report from an embassy attaché speculating on the Soviet Union’s atomic potential. “It is vital to U.S. security that our government should be adequately and currently informed on this subject,” Kennan urged. It was “out of the question that adequate information can be obtained through the normal channels.” His conclusion was discreetly worded but very clear. “Large-scale special efforts on various lines in this direction are therefore justified,” he said. “I consider it the clear duty of the various interested agencies of our government to determine at once in Washington the measures which our government should take to obtain information with respect to Soviet progress in atomic research.”

This was too hot for even the coded communication facilities of the embassy. Kennan gave his message to General Deane to carry to Washington by hand. In a covering letter to Harriman, Kennan added a personal plea “to see that everything possible is done to obtain information on Russian progress along these lines.”

When he read Kennan’s memo, Acheson dismissed the parts about the danger of trying to bring the Soviets into a partnership for atomic control. But the proposals for an intelligence-gathering system caught his eye. Kennan had mentioned that he thought his message was not the proper “vehicle” for “detailed recommendations,” but added that he had other ideas he would be willing to discuss. In the margin next to these words, the acting Secretary scribbled a note: “This would be asked for. D.A.”

The Office of Strategic Services, the wartime intelligence agency headed by William Donovan, had been disbanded by Truman at the end of September. There was at the time no specified agency designated to spy on the Soviet Union. When the CIA was being formed a year later, shortly after Kennan returned from Moscow, he quietly spent a month on its payroll as a “special consultant” to the new director of Central Intelligence, General Hoyt Vandenberg.

The London Conference ended up as a disaster for Byrnes. The Americans, Soviets, and British could not even agree on a final communique about the postwar governments of Europe. Byrnes’s “bomb in his pocket” did little more than provoke what was in all likelihood a clumsy Soviet charade. At the end of a long reception, Molotov got up, appearing drunk, and made a toast: “Here’s to the atomic bomb. We’ve got it.” An aide grabbed him by the shoulders and quickly led him from the room.

Byrnes had curtly dismissed Harriman’s request to come to London for consultations. He would be too busy to see him before the start of his meetings with Molotov. This was more than just a personal insult to Harriman; it was a denigration of his duties as ambassador to Moscow. Harriman had wanted to discuss his own resignation, and the brusque lack of regard for his advice only strengthened his resolve. So Harriman went to London anyway, and at the end of the conference, in early October, the two men finally had dinner.

“Now that we’re in this jam,” said Byrnes, mixing his metaphors, “you’ll have to wait and get the train back on the rails.”

Harriman, in fact, was actually considering going back to his own rails, the Union Pacific. But he was not, if truth be told, all that anxious to leave his rarefied work for a return to private life in New York. He enjoyed his growing fame throughout Europe and his surprising celebrity wherever he traveled in Russia.

Although he was very close to his bright and charming daughter Kathleen, who had been a great hit as Spaso House hostess, Harriman rarely saw much of his wife, Marie, who had stayed back in New York. During his tenure in London and his frequent visits there after moving to Moscow, he had enjoyed a noted friendship with Pamela Churchill, or at least one that was noted by the gossip columnists.

Pamela, the daughter of the 11th Baron Digby, had married Winston Churchill’s son, Randolph, shortly after the war began, when she was nineteen. A brilliant woman of striking beauty, she and her newborn son, Winston II (later a member of Parliament), had graced the cover of Life magazine about a year later. But the marriage soon soured, and in 1946 she sought a divorce, charging that Randolph “seemed to prefer a bachelor’s existence.” Her name was subsequently linked with a wide array of prominent men, among them Ali Khan, Fiat heir Giovanni Agnelli, Baron Elie de Rothschild, and newsman Edward R. Murrow. Averell Harriman especially caught her eye. “He was the most beautiful man I ever met,” she recalled forty years later. “He was marvelous, absolutely marvelous-looking, with his raven black hair. He was really stunning.”*

Byrnes found Harriman somewhat easier to re-enlist than Acheson had been, though neither proved all that difficult once properly stroked. The one thing Harriman wanted was another chance to deal with Stalin directly. So Byrnes promised him a letter from Truman, for delivery to Stalin personally, that would serve as a basis for meeting. That accomplished, Harriman set out for a visit to Germany and Eastern Europe on his way back to Moscow.

Traveling with him was his friend McCloy, who had embarked on a six-week round-the-world tour that would be his final official act as Assistant Secretary of War. The two men met in London at the tail end of the Foreign Ministers’ Conference, discussed their mutual worries about Byrnes and the bomb and the Soviets, then took off together for the Continent.

In Vienna, Harriman and McCloy were feted at a lavish reception attended by Marshal Ivan Koniev, the commander of Soviet forces in Austria. Once again the American military’s rosier view of relations with Russia was evident. In his notes at the time, Harriman derided the “exaggerated importance” that the U.S. military put on the cooperation they had received on “relatively small issues.” There was a tendency, Harriman noted, “to think that the politicians were making their work more difficult.”

McCloy found himself caught between Harriman and the military. Everywhere they went, the Russian officers seemed so friendly, so profuse in their claims of comradery. From Eisenhower on down, American officers assured McCloy that given the chance, cooperation was possible. Yet he could not escape the gloomier talk, the worries about Soviet motives expounded not only by Harriman but in almost every conversation with foreign officials and American diplomats.

It was a profound enigma, but one perhaps better left to more profound men. So McCloy simply recorded the riddle in his notebook, noting that it was of “prime importance” for statesmen to figure it out. McCloy was not a conceptualizer. He was an implementer. The problems of coal distribution and communication services were to his mind even more pressing, and these were things he could get on with.

There was one thing on which Harriman and McCloy heartily agreed: America could not avoid the global involvement that had come with victory. They were shaken by the destruction in Budapest, that once-glorious gem on the Danube which had been ravaged by weeks of street fighting. Yet there was jubilation in the city when they arrived: a free election had been permitted by the Soviet occupiers and the anti-Communist Smallholders Party had won an unexpected majority.

As McCloy and Harriman headed for the American mission, they found their way blocked by jubilant Hungarians. “There was an enormous crowd celebrating the victory under the American flag,” Harriman recalled. “It made me feel very humble to recognize how much these people looked to the U.S. as the protector of their freedom.” As the crowd surged up to their car and cheered, the two men were awed, even slightly scared by the responsibility such a role would carry. “Here was the hope of the world,” McCloy remembers thinking, “the American flag.”

Harriman and McCloy agreed as they surveyed the crowd that the American sentiment to pack up and go home, to demobilize and wash hands of European entanglements, must be mightily resisted by people like themselves, those who shared a unique understanding of the role America should and must play. The global duties that the American public, with its insular perspective, had forsaken after the last war could not be shirked once again.

The experience stiffened Harriman’s resolve that Eastern Europe should not be abandoned. “I simply could not accept the view that we ought to walk away and let the Russians have their sphere,” he said, recalling the incident. Kennan might advocate such a course, Harriman thought, but only because he was insensitive to the plight of those in the helpless nations involved.

To McCloy, there was something “terrifying” about the incident. It showed how dependent Europe was on the U.S. for its future stability. “We give the population hope against the Russian fear,” he cabled in a long report to Washington. His own eyes finally convinced him of what Harriman had long been insisting: the Soviets were embarked on a “determined” policy of dominating the economies and societies the Red Army controlled. In a recommendation that could have been written by Harriman, McCloy urged that U.S. loans and reconstruction aid to Eastern Europe be held up until the Soviets reduced their presence. In addition, American troops should remain in Austria pending the Soviet withdrawal. “Opposition to Russian pressures gains encouragement,” he said, “by our mere presence.”

While McCloy continued on to the Far East, Harriman headed back to Russia, determined to go straight to the source to determine what the Soviets were really up to. Armed with his letter from Truman, the ambassador called on Molotov to request an interview with Stalin.

The Soviet leader was on a long vacation, said Molotov, who offered to pass the letter on himself. “Where is he?” Harriman asked. “I can join him.” Molotov, finding the suggestion somewhat incredible, said he would see if that was possible. It was a testament to Harriman’s unique stature in the Soviet Union that the word soon came back that he was invited to Stalin’s secluded dacha in the Black Sea resort of Gagra.

The basic question, as Harriman saw it, was whether the U.S.S.R. wanted to follow a policy of international cooperation, which involved working out some form of “collective security” arrangements with the West, or whether it had decided to pursue a unilateral policy (often referred to in the Soviet Union as “isolationism”), which would entail an aggressive expansionism in pursuit of its own security goals. He found that Stalin seemed to be of two minds on the question, but that he was leaning toward the latter course.

Welcoming Harriman to his white stucco villa, Stalin led him into a mahogany-paneled office where they had two days of talks in late October. International cooperation was still possible, Stalin seemed to indicate on the first day, but it had to be a two-way street. The Americans, he said, were demanding a voice on Soviet-dominated control commissions in Eastern Europe. Yet the U.S. had been adamant in refusing the Soviets any say in the occupation of Japan, a country that had historically been a security threat to them.

Harriman, who took pride in having resisted Stalin’s demands on the night Tokyo surrendered, was not anxious to permit the Soviets a toehold in Japan. But he did believe they should be given some voice, subject to General MacArthur’s final authority, if only as a way to strengthen American claims in the Balkans and Eastern Europe. “We can’t get away with this brush-off,” Harriman had scribbled to Byrnes at the London Conference when the Secretary refused to discuss the issue. Byrnes finally agreed to let Harriman and Bohlen draft a note to Molotov saying that the U.S. would discuss the Japanese occupation after the conference ended.

Although he had no authority to do so, Harriman assured Stalin that an arrangement could be worked out for an Allied control council or commission under MacArthur’s authority. As Harriman pointed out to Washington: “Japan has for two generations been a constant menace to Russian security in the Far East and the Soviets wish now to be secure from this threat.”

On their second day of talks, however, Harriman found Stalin to be far less agreeable. Maybe, the Soviet leader said, it did not really matter what happened in Japan. He had never favored a policy of unilateral action, he claimed, but now it might be inevitable. “Perhaps,” Stalin added, “there is nothing wrong with it.” Harriman concluded that the Soviets had decided that postwar cooperation with the West was not to their advantage. “The Soviet leadership,” he later speculated, “had discussed and settled on a new policy for the postwar period, a policy of increased militancy and self-reliance.”

Even though he had long been an advocate of firmness, the prospect of a complete breakdown in cooperation upset Harriman. So too did Washington’s dithering about setting up a joint control commission for Japan. Despite the reluctance of the State Department to take up the matter, Harriman immediately embarked on a series of discussions with Molotov designed to allow the Soviets some say in the occupation in return for greater American involvement in Eastern Europe.

What Harriman did not know was that Truman and his advisers were enmeshed in their own negotiations on the issue of Japanese control—not with Moscow but with their own imperial commander there, Douglas MacArthur. Many of the isolationists who before the war resisted American entanglement in the affairs of Europe had evolved into Asia Firsters, advocates of forceful and unilateral American actions to control the Pacific. Their new hero was General MacArthur, who wanted nothing to do with the Soviets in his Pacific theater and cared little for what effect this would have in Central Europe.

In the first of many efforts by the Truman Administration to rein in its high-handed Pacific commander, John McCloy was given the mission of negotiating with MacArthur. When he arrived in Tokyo on the last leg of his global tour, McCloy found that MacArthur had graciously driven for two hours to meet him at the airport. But in a series of long sessions over the next three days the general’s short temper was snapped by McCloy’s arguments that the Soviets be given some voice in the control of Japan. “He became very agitated,” McCloy wrote in his diary. “He talked of the great opportunity we had in the East, of the God-given authority we now had here, of what a mess things were in Europe, of the threat of the Russian Bear.”

The Assistant Secretary, courtly and calm, found it hard even to get in words edgewise. “It became a sort of shouting contest,” he noted. “I told him that the Russian relation was one that had to be looked at from a world point of view. We had great interests in middle Europe. We could not take a unilateral position in the Pacific and still press for a satisfactory solution elsewhere in the world.”

McCloy discussed MacArthur’s stubborn attitude in a teletype conversation with Acheson and Bohlen in Washington. Acheson began by arguing that a “face-saving” solution giving the Soviets some voice in the occupation of Japan “may be determinative of future cooperation” between Washington and Moscow. Harriman was discussing this very issue with Stalin, Acheson added, so the dispute with MacArthur must be cleared up quickly.

McCloy wired back that he and MacArthur may have found “an arrangement that would be satisfactory.” Representatives of Allied countries, including the Soviet Union, could be invited to join a “Council of Political Advisers” that would recommend to MacArthur policies for the treatment of occupied Japan.

Would the general, Bohlen asked, be willing to be a member of the “council” rather than treating it as merely an outside advisory group? “As Bohlen puts it,” McCloy teletyped back, the idea “carries with it just the implication that MacArthur wishes to avoid.” The general, he said, was willing to accept only an “advisory” panel that would send him recommendations. Replied Acheson: That was even less than the Russians were granting American officials in the Balkans.

In the end, the Soviets were given no real authority. As Harriman discovered in his conversations with Stalin, this was perhaps all for the best: the Kremlin had by now clearly decided to pursue a unilateral policy of asserting its own power without regard to considerations of international cooperation. The U.S., he concluded, would simply have to adjust itself to this new reality.

When McCloy returned home, he felt for the first time the need to speak out. No longer could he serve as merely an administrator of Stimson’s ideas; Stimson was gone and people were looking to McCloy for insights of his own. His brother-in-law Lew Douglas, who was then president of the Mutual Life Insurance Company and would later become ambassador to Britain, asked him to talk about his world trip at the annual dinner of the Academy of Political Science in New York. NBC radio offered him air time for a similar report.

McCloy had none of the eloquence of an Acheson. Even though he had stayed up past 1 A.M. one night to compose his speech, his remarks tended to ramble. Yet there was a crucial point he wanted to make, and he hammered it home: “the need for American leadership to bring this world into some semblance of balance again.” People all over looked to the U.S. as “the one stabilizing influence” that could protect their freedom. “A shudder runs through them when they hear the increasingly loud demand for the removal of our troops, which they consider the abandonment of our interest in their parts of the world.”

The isolationism that followed the last war, McCloy emphasized, gave rein to forces hostile to democracy. This time America should not retreat from involvement, either militarily or politically. “The people of the world will not believe, unless we convince them, that we have what it takes to carry through in peace.”

McCloy also touched on the other topic troubling him: the Soviet Union. “Everywhere you go, that topic is up,” he reported, “the concern over Russia’s ambitions, how far she is going to go, how to deal with her.” He offered no judgments, no solutions, just an admonition: “It is quite clear that this is the A-1 priority job for the statesmen of the world to work out.”

A crucial personal decision now faced McCloy: What role would he play in this A-1 priority job? His friends who had left their lucrative careers to join the wartime effort were all considering a return to private life now that the fighting was over. Acheson had made an attempted break from Washington only to be dissuaded after three days. But Acheson had a greater taste than McCloy for the public spotlight; he also had a bit more money saved up from his days as a lawyer as well as a wife with some wealth of her own. Harriman, likewise, had made rumblings about leaving, and insisted that he still planned to in the near future.

Upon returning from his world tour, McCloy was presented with a surprising offer from Byrnes. Now that Harriman was talking about resigning, the Secretary said, McCloy was the President’s choice to be the next ambassador in Moscow. “It was most flattering and disturbing,” McCloy noted in his journal, “for no one can deny the challenge that lies ahead.” Another offer came from Amherst, which wanted him to be its next president.

Throughout the fall, McCloy agonized about his future. It would be difficult, he wrote, “to get back to humdrum things.” But he badly needed to make money again, to support his family better; perhaps as a legacy of his childhood poverty, McCloy always seemed worried about not having enough money. Extremely lucrative offers were coming in from the top law firms of Wall Street, including one from Milbank, Tweed, Hope and Hadley to become a name partner.* He wanted to spend more time with his son and daughter. “Now that the war is over,” little Johnny had said at dinner one night, “can I have my daddy back too?”

Finally he decided to reject the chance to become Spaso House’s next ambassador and to return to the practice of law, adding his name to the partnership of Milbank, Tweed, which handled the affairs of the Rockefeller family and the Chase Bank. “We are at a windy corner of history,” he wrote in his journal. “As interesting as it is, I must make my living again.” But he would do so, he vowed, in the tradition of such people as Root and Stimson, men who had distinguished themselves in private careers while continually answering the call of public service.

The emulation was quite conscious. That September, when Stimson presented him with the Distinguished Service Medal, McCloy had noticed “the steady gaze of Elihu Root” from the portrait hanging behind the Secretary’s desk. “I felt a direct current running from Root through Stimson to me,” he wrote in his diary. “They were the giants.”

Thus it was hardly surprising that as he re-entered private life, McCloy became actively involved in the Council on Foreign Relations. Founded in 1921, this respected bastion of top lawyers and bankers and statesmen was the wood-paneled reification of the Root-Stimson tradition. During the war, McCloy and Lovett used to flip through the club’s roster to come up with names of people who might be called upon to serve their government. Now it would serve as a perfect base for his own special talents.

The council was not suited to those who sought an ideological pulpit; it was, instead, a place where stable bipartisan consensus could be forged, where behind-the-scenes discussions could be held, where wise counsel could be sought. Such was an atmosphere in which McCloy could thrive. He had none of Acheson’s brilliance, nor Kennan’s conceptual vision, nor Harriman’s boldness as a top-level bargainer, nor Forrestal’s philosophical fervor. Yet though he was only an outgoing Assistant Secretary, McCloy was already revered for his discreet counsel, his rocklike wisdom, his reassuring steadiness.

At the end of his European tour, McCloy was feted at a black-tie dinner in the council’s newly acquired Park Avenue home, a 1919-vintage English Renaissance marble mansion. There he outlined his vision of America’s righteous mission in the emerging global era. “Thus far we have gotten along with Russia fairly well,” he said in response to a question. The Soviets could never hope to match America’s economic and moral might in the world. “Russia’s concepts and example will wilt before ours,” he had concluded, “if we have the vigor and farsightedness to see our place in the world.”

Robert Lovett received his Distinguished Service Medal from Stimson at the same time as McCloy. Despite the weighty gaze of Elihu Root, it was a jovial occasion, with the two Imps of Satan recalling old tales, joking with their departing mentor, and posing for countless photographs. For Lovett, secure in the knowledge that he had done his job well and that the government could function without him, there was no hesitation about leaving public service for the time being. He was already making arrangements to resume his partnership in Brown Brothers Harriman.

Lovett’s Distinguished Service citation, which Stimson personally wrote, spoke of the fact that “he early envisioned the vast possibilities of air power.” Lovett’s contribution had been far more than that of an able administrator. He had come to represent an important yet intangible quality, one that Stimson alluded to in lauding his “diplomatic tact and wise counsel.”

With his great sense of inner security, Lovett seemed devoid of personal ambition or ulterior motives. His discreet and selfless style of operating came to be idealized by others as the bench mark for a certain breed of public servant. It was a standard that had long been associated with Stimson and was now coming to be known, in newspapers and conversation, as that exemplified by Lovett. “The problem is to keep such men in public service in peace as well as war,” The New York Times wrote in marking Lovett’s departure that November. “The more prosaic tasks of government in peace also need men of knowledge, of courage, of vision, qualities Mr. Lovett has shown in such full measure.”

The impact of a “classic insider’s man,” as journalist David Halberstam would later call Lovett, is generally harder to quantify than that of more assertive personalities, such as Harriman or Acheson. But within certain circles, Lovett was already considered to be a man of enormous influence. More than any of his colleagues, he had come to be regarded by those within the Wall Street and Washington Establishment as a touchstone of things safe and sound. Because of the respect others had for his impeccable credentials and motives, he imparted a seal of approval upon people and policies he supported. When Lovett brought people together, there was the unspoken sense that they were the right sort of people, ones who could be trusted to put aside personal or partisan considerations for the good of the country. Consequently, part of his importance in Washington by 1945 was his role as the reliable focal point for a group of bankers, lawyers, journalists, and public officials who viewed themselves as the backbone of a nonpartisan foreign policy elite.

As he had promised his wife the day the war ended, Lovett moved back to New York in time for Thanksgiving. The accumulated exhaustion of seven-day work weeks had taken a toll, as did the ailments, both real and imagined, on what he called his “glass insides.” That winter he underwent gallbladder surgery, which was followed by a month of recuperation at his vacation home in Hobe Sound, Florida.

After he finally returned to his rolltop desk in the Brown Brothers Harriman Partners’ Room, Lovett settled into the comfortable life of a prominent Wall Street banker. He served on the boards of such companies as the Union Pacific and New York Life Insurance and was a trustee of the Carnegie Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation. His clubs included the Century Association and the Links in New York and the Creek in Locust Valley. Yet he discovered that his advice was still much sought in Washington. He would find himself making frequent trips down there at the behest of Acheson or Harriman or occasionally the President. His apparent lack of desire to re-enter government served only to make him seem more indispensable to those who would eventually see that he did.

“I can state in three sentences what the ‘popular’ attitude is toward foreign policy today,” Acheson told the Maryland Historical society in November of 1945. “1. Bring the boys home; 2. Don’t be a Santa Claus; 3. Don’t be pushed around.”

On the first two counts, Acheson’s own attitude was clear: he was against the rush to demobilize and felt that America’s involvement in rebuilding a prosperous Europe was in its own economic and political interest. On the third point, however, his ideas were still a bit hazy. He resisted the growing anti-Communist truculence sweeping parts of the country, yet he was just as certainly opposed to having the U.S. pushed around. McCloy’s “A-1 priority job,” figuring out what the Soviets were up to, was still quite a nagging riddle for the new Under Secretary.

Acheson got a taste of how explosive the issue could be when he agreed to address a New York meeting of the Soviet-American Friendship Society in November. Armed with a speech suitable for a Frankfurter seminar, he arrived at Madison Square Garden to find a vociferous and crowded rally ready to be inspired. And inspired they were: An orchestra played revolutionary marches, the crowd stomped and chanted, and Paul Robeson, the great bass singer who later became a Soviet citizen, boomed forth a rendition of “Ole Man River” that just kept rolling through a crescendo of protest to a defiant finale. The Very Reverend Hewlett Johnson, the “Red” Dean of Canterbury Cathedral, also received a thunderous ovation. “He sashayed around the ring like a skater,” Acheson reported, “his hands clasped above his head in a prize fighter’s salute.”

Acheson was eloquent in conveying his sympathy for the Soviets’ security aims. To understand them, he said, an American would have to imagine what it would be like if Germany had invaded the U.S., destroyed industrial centers from New York to Boston to Pittsburgh, ruined a large part of the Midwest’s breadbasket, and killed a third of the population. To Acheson this made a compelling case for allowing the Soviets at least some form of sphere in Eastern Europe. “We understand and agree with them,” he said, “that to have friendly governments along her borders is essential both for the security of the Soviet Union and the peace of the world.”

But the situation was not all one-sided. Although Acheson, out of deference to his audience, toned down the growing qualms he had about Soviet police-state tactics, he did not omit them altogether. “Adjustment of interests,” he said, “should take place short of the point where persuasion and firmness become coercion, where a knock on the door at night strikes terror into men and women.” Amid a rising chorus of boos and catcalls, Acheson hurried on through his speech, tossing quotations from Molotov and Stalin in hopes of calming the fury he had ignited. “But I had shown my true colors,” he later wrote. “Those who took their red straight, without a chaser of white and blue, were not mollified.”

When he finished, a policeman touched him on the arm. “Come,” he said, “I can show you a quiet way to your car.” At a friend’s house, a glass of Scotch was waiting. Acheson had learned a valuable lesson: The difficulty of figuring out the Soviet riddle paled in comparison to facing an American audience—on either side of the issue—without a clear and forceful answer to their liking. The hissing that came from the left that evening would later be matched by that from the right. In fact, his presence at the Madison Square Garden rally would, ironically, be cited during the McCarthy era as evidence of his softness on Communism. “This seemed to me,” he later mused, “to add a companion thought to Lincoln’s conclusion of the impossibility of fooling all of the people all of the time, the difficulty of pleasing any of the people any of the time.”

What Acheson had been trying to express, and indeed what he had come to believe, was the new State Department line formulated by Chip Bohlen. As the department’s Soviet expert, Bohlen had been wrestling with the idea of Eastern Europe as a Soviet sphere. He still could not buy Kennan’s view that the area should be written off totally to the Soviets. The U.S., Bohlen and others genuinely believed, had a moral interest in protecting freedom and encouraging democratic ideals. Yet he had come to accept, as had officials ranging from Stimson to Harriman, that the Soviets’ insistence on protecting their security interests along their borders had some merit.

To that extent, Bohlen concluded, Moscow was entitled to some sort of sphere of influence, despite the high-minded rhetoric of the Atlantic Charter, and to “friendly” states next door. The problem was defining what “friendly” meant.

The difficulty, as Bohlen saw it, came when the Kremlin insisted “on complete Soviet domination and control over all phases of the external and internal life” of countries within its sphere. Such police-state repression was an anathema not only to Americans, but to principled and freethinking people everywhere. Besides, this total domination (at least in Bohlen’s eyes, if not the Kremlin’s) was unnecessary for Soviet security purposes. Somehow, he figured, there must be a way to establish governments in Eastern Europe that were “friendly” to the Soviets and yet did not depend on repressive Stalinist tactics to stay in power.

Thus Bohlen proposed making a distinction between “open” spheres, in which the Soviets exercised “legitimate influence” over matters relating to their security, and “closed” spheres, in which there was “illegitimate extension of such interest in the direction of domination and control.” He explained it all in a memo to Byrnes and Acheson in October of 1945. “The U.S. should not and indeed could not assist or even acquiesce in the establishment by the Soviet Union of exclusive spheres of influence in Central and Eastern Europe by means of complete domination,” he wrote. “On the other hand, we should not in any sense attempt to deny to the Soviet Union the legitimate prerogatives of a great power in regard to smaller countries resulting from geographic proximity.”

The distinction was immediately embraced by Byrnes as the new definition of American policy, which he enunciated in a major New York speech. Truman proclaimed it too, as did Acheson at Madison Square Garden.

There were, however, some sticky problems with the policy. First of all, how could the U.S. convince the Soviets that the regimes being set up by the Red Army should permit the people some semblance of personal freedom? Bohlen hardly provided much of an answer when he wrote that the U.S. “should leave the Soviet Government in no doubt as to the automatic and inevitable results” of imposing a closed sphere. That seemed to be a prescription for further fiascoes like the two-year wrangle to get four token ministers temporarily into the Polish Cabinet.

Another drawback was that Bohlen’s two-pronged policy would be difficult, at best, to sell to the American public. It certainly had not played well before the Soviet sympathizers in Madison Square Garden. Byrnes was already running into criticism from diehards in the Sentate who thought he was too willing to give away the Balkans and Eastern Europe to the Soviets, along with the bomb. Indeed, the middle approach appealed neither to the left nor the right, neither to Wilsonian idealists nor even fervent realists like Kennan.

The thorniest problem of all was Harriman’s old domino dilemma. Given a friendly sphere (either “open” or “closed”), would the Soviets set their sights on the next layer of countries? Would a sphere that included Russia’s Balkan neighbors soon swallow Greece? Bohlen’s middle road did nothing to answer the A-1 question: How much did the Soviets want and how far were they planning to go?

The hard-line attitudes of Harriman and Kennan had been spawned by their revulsion over the Kremlin’s fanatic insistence on imposing rigid controls on its own society and those that fell into its orbit. Officials who still hoped for closer Soviet-American friendship, such as Acheson and Bohlen, and those who had not yet sorted out the complex questions, such as McCloy and Lovett, would likewise soon see the need for a firmer stance. For them the catalyst would be evidence that Moscow was setting its sights on areas that lay beyond the countries its armies had liberated during the war, areas that were of clear strategic importance to the West.

At the theater in Moscow one evening in late November, Harriman had a depressing conversation with former Foreign Minister Maxim Litvinov, who was brooding about his own ouster from the Kremlin inner circle and the abandonment of the policy of cooperation he had once advocated. When Harriman asked what could be done about the breakdown in relations, the former Foreign Minister gloomily replied, “Nothing.”

In a cable to the State Department about his chat with Litvinov, Harriman sketched out the evidence, accumulated since his Black Sea meetings with Stalin, that the Soviets were pursuing a unilateral expansionist policy. Their attitudes toward Bulgaria and Rumania had hardened, he reported, and the Chinese Communists had been invited by the Red Army into Manchuria. Even more troublesome was evidence that they were probing into other areas. They were fomenting the revolt in northern Iran, he said, and putting new pressure on Turkey for naval bases on the Dardanelles.

The question was why. As he sat down to consider the causes of the apparent Soviet decision to go it alone, Harriman’s mind began to focus on an important new element: the atomic bomb. In a long analysis for Washington, he explained that Soviet leaders should feel more secure than ever. “With victory came confidence in the power of the Red Army and in their control at home, giving them for the first time a sense of security.” What had happened? “Suddenly the atomic bomb appeared,” Harriman wrote “This must have revived their old feeling of insecurity . . . As a result it would seem that they have returned to their tactics of obtaining their objectives through aggressiveness and intrigue.” Even though the link between Moscow’s growing orneriness and the atomic bomb might have seemed somewhat tenuous, both Kennan and Harriman had long believed that paranoia and insecurity were the major sources of the Soviets’ expansionist instincts.

Harriman had no suggestions to make. His message, he noted, was only meant as “a partial explanation of the psychological effect of the atomic bomb on the behavior of Soviet leaders.” But it reached Washington at a very critical time.

In mid-November, shortly before Harriman sent his analysis, Truman had held a summit with the Prime Ministers of Britain and Canada, America’s two partners in developing the bomb. Contrary to what Stimson had urged, and contrary to what Acheson and Bohlen were recommending, the three leaders decided to submit the issue of atomic control to the U.N., rather than first approach Moscow with a plan.

But by later in the month, even Byrnes had come to realize that it was best to bring the matter up directly with the Soviets before any U.N. meeting. He proposed to Molotov a late-December conference of the American, British, and Soviet Foreign Ministers in Moscow. The bomb would be the first order on the agenda, followed by a discussion of the problems in Eastern Europe, Japan, and elsewhere.

A committee was formed to flesh out the American proposals for atomic control along the lines that Stimson, McCloy and Acheson had advocated in September. Bohlen and Acheson’s assistant Herbert Marks were designated as the State Department representatives. The Soviets, they proposed, should be asked to cosponsor the U.N. resolution setting up an atomic commission. Control would be accomplished through a series of related steps that included exchanging scientific information, sharing data on natural resources such as uranium, and establishing safeguards to prevent any nation from producing nuclear weapons on its own.

One important element was that there was no firm link in timing between the acceptance of verifiable safeguards and the sharing of information. That was too much for Forrestal. “The proposed basis for discussion goes too far,” he phoned Byrnes. No information should be shared until guarantees had been adopted to prevent any country from building its own bomb. When the plan was finally presented to Senate leaders they were even more outraged. “We are opposed to giving any of the atomic secrets away,” said Senator Vandenberg, “unless and until the Soviets are prepared to be policed by the U.N.” Expressing little regard for their concerns, Byrnes departed for Moscow.

Even as Byrnes was in the air, the horrified senators were demanding a meeting with the President. Acheson, who had earned the dubious duty of being Vandenberg’s handler, was summoned to the White House to mediate. Truman was convinced that Soviet cooperation was crucial, and he showed little interest in the disputed details of the step-by-step approach. But after the showdown he instructed Acheson to convey the senators’ concerns to Byrnes.

The entire issue seemed to hold surprisingly little interest to the Soviets. Molotov, in fact, insisted that atomic control be placed last on the agenda at the Foreign Ministers’ meeting. He even attempted a feeble barb about the bomb at one of the banquets, but Stalin peremptorily put him down. “This is too serious a matter to joke about,” he said. “I raise my glass to the American scientists and what they have accomplished. We must now work together to see that this great invention is used for peaceful ends.”

With little debate, the Soviets accepted a vague proposal to set up a U.N. commission on atomic control. There was no discussion of what steps would come in which order. The only Soviet demand, which the Americans and the British accepted, was that the commission should report to the Security Council, where the Soviets had a veto, and not to the General Assembly.

The Soviets were far more interested in winning Western recognition for their “friendly” regimes in Eastern Europe. When the Foreign Ministers could not reach an agreement on this issue, Stalin invited Byrnes, Harriman, and Bohlen to the Kremlin to see what could be worked out. The cosmetic concessions offered by the Soviet leader mirrored what he considered to be the token ones the U.S. had made regarding Soviet participation in the occupation of Japan. A few non-Communists could be added to the Bulgarian and Rumanian governments, Stalin said, in return for Western recognition.

Byrnes, who was anxious to bring home some sort of an agreement, leaped at the proposal. But neither Bohlen nor Harriman thought that it amounted to much. Stalin’s concessions, Harriman later said, “did not alter the brute facts or in any way loosen his grip on Eastern Europe.” They were also dismayed by Stalin’s cavalier attitude about Iran. Warned that if Soviet troops did not stop fomenting unrest in the northern region of that country the matter would be raised at the U.N., Stalin replied with a shrug: “This will not cause us to blush.”

While his colleagues were at the Kremlin, Kennan was nervously pacing and awaiting their arrival at the Bolshoi Theater. A special performance of Sergei Prokofiev’s new ballet Cinderella had been scheduled, and it was being delayed pending the appearance of the Americans. Just as Kennan was about to phone the embassy, a Soviet secret policeman, knowing full well what was agitating Kennan, told him the party was on its way.

More than ever, Kennan felt excluded and ignored. He had handed Byrnes his secret memo on the folly of sharing atomic secrets with the Soviets, but the Secretary seemed to have no interest in his views. “His main purpose is to achieve some sort of an agreement,” Kennan noted in his diary. “He doesn’t much care what.” The accords being worked out on Eastern Europe, Kennan pronounced, were “fig leaves of democratic procedure to hide the nakedness of Stalinist dictatorship.”

Dismayed by the unprofessionalism of the politicians who thought they could handle diplomacy, Kennan began setting down a series of rules for dealing with the Russians. “Don’t act chummy with them,” he began. “Don’t assume a community of aims with them which does not really exist. Don’t make fatuous gestures of good will.” When the topic was brought up at a lunch with Alexander Cadogan and other members of the British delegation, Kennan and Bohlen unleashed their shared views. Noted Kennan: “I think he and I rather shook Cadogan’s composure with our observations on the techniques of dealing with the Soviet government.”

Harriman, who was always scrupulous about stroking the Presidents he served, was surprised when Byrnes announced that he was not planning to send regular cables back to Washington. “I can’t trust the White House to prevent leaks,” said the Secretary. When Bohlen brought up the same matter, Byrnes sharply said that he knew when it was necessary to report and when it was not. “I was put in my place,” recalled Bohlen, “and I stayed there.” Little did Byrnes realize that, back in Washington, Acheson was facing an annoyed President and some disgruntled senators anxious that Byrnes be the one who was put in his place.

Senator Vandenberg found out what Byrnes had done in Moscow by reading the newspapers. Worse yet, so did Truman. Neither was happy. The nebulous agreement on atomic energy contained no commitment to share information until the U.N. had somehow worked out a system of inspection and control. But Vandenberg, determined that this point be made more explicit, howled in protest to Acheson before Byrnes had even arrived home.

Off to the White House the two men marched to hear Truman’s assurances once again. This time the senator wanted them in writing. Truman sent him back to the State Department with Acheson, and there the two men negotiated an acceptable clarification. “Complete and adequate security must be part of each stage” of a plan for joint atomic control, it emphasized. Feeling somewhat humiliated, Truman agreed to issue the statement.

Thus the President was not in the best of moods when Acheson had to irritate him even further. Overjoyed with what he considered a great set of breakthroughs, and oblivious to the mood in Washington, Byrnes cabled home to arrange time on the radio networks so that he could tell the nation of his triumphs.