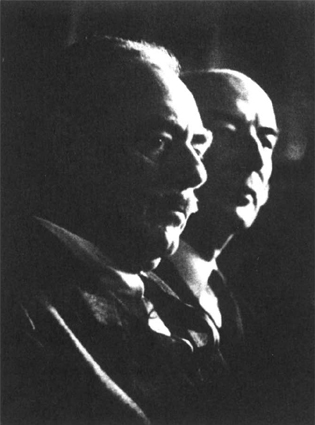

Acheson and Lovett testify before Congress

Disaster at the Yalu

In late October of 1950, U.S. and South Korean troops made sporadic but murderous contact with Chinese Communist troops in the barren hills of North Korea. Chairman Mao announced on November 2 that they were “volunteers” who had joined the North Korean Army to protect their homeland’s hydroelectric plants along the Yalu River between Korea and China. Carrying old Japanese rifles and wearing cloth shoes, the Chinese were dismissed by MacArthur in a cable to Washington as “not alarming.” Field commanders, however, reported that while the Chinese troops were poorly equipped, they were well disciplined. As a precautionary measure, MacArthur decided to take out the bridges over the Yalu. Washington was routinely informed.

Lovett saw the cable less than four hours before the first bombs were scheduled to fall. Looking at a map, he decided that the air strikes were a terrible idea. They might provoke the Chinese, but they would not stop the flow of troops, since the river was shallow and easily forded. He moved quickly to stop the mission, enlisting Acheson and Marshall.

MacArthur was indignant. He protested that Washington’s interference “threatens ultimate destruction of forces under my command.” He demanded that his cable be shown to the President, “as I believe your instructions may well result in a calamity of major proportions.”

Such dire warnings, coming from someone who only a few days earlier had dismissed the Chinese incursions as “not alarming,” made Washington wonder—not so much about the Chinese, who had suddenly broken off fighting and vanished back into the hills, as about MacArthur.

Lovett, in particular, was worried. He lost his usual geniality when he talked about the vainglorious general; his humor became more wicked. At meetings Lovett would imitate MacArthur flipping the hairs of his head to cover his bald spot. “You know those wisps of hair he so carefully combs over the crown of his head?” Lovett would ask. “Actually, he has no hairs on his head. It grows out his back and curls up around over his head.”

General Marshall, too, was uneasy. He thought MacArthur’s strategy for conquering the North was ill-conceived. He believed that MacArthur had wasted valuable time mounting another landing after Inchon, and allowed too many remnants of the defeated North Korean Army to slip out of the South. Then MacArthur had split his command into two forces, the Eighth Army and X Corps, driving up either side of the long spine of mountains running north-south through the country. It was difficult for the two columns to communicate, much less relieve each other. At nine-thirty meetings in the Pentagon, Marshall bore in on his subordinates with specific questions about troop movements and logistics. “How many men are in that unit?” he would demand. The Pentagon officers, never too sure of what MacArthur was up to, would give vague answers, and Marshall would say, “Never mind about how many. How many?”

Washington had no way of knowing what was really happening on the ground. The Pentagon did not learn the extent and nature of the firefights with the Chinese “volunteers” for almost a week. CIA reports about the enemy were so contradictory as to be meaningless. MacArthur was suspicious of the fledgling agency and sought to keep it uninformed. His own intelligence network was run by sycophants. General Charles Willoughby, head of the Far East command’s intelligence, was inundated with raw data, but he had trouble accurately sorting through it. He knew, for instance, that the Chinese had half a million soldiers in Manchuria, just across the Korean border, but somehow never quite grasped the significance of this statistic, or called it to Washington’s attention. He was also distracted that fall: he was writing a eulogistic history of MacArthur’s Pacific campaigns against the Japanese.

Despite the intelligence lapses, Dean Acheson later said, “We had the clearest idea among ourselves of the utter madness and folly of what MacArthur was doing up north.” Yet, as he later wrote Richard Neustadt, “We sat around like paralyzed rabbits while MacArthur carried out this nightmare.”

Why? The question would gnaw at Acheson the rest of his life.

The written record discloses no shortage of discussion in Washington about MacArthur and his war plans. Between November 10 and December 4, the Secretaries of Defense and State and the Joint Chiefs of Staff met three times in the Pentagon War Room, the two Secretaries met five times with the President, and Acheson himself talked five more times with the President. The minutes of the meetings repeatedly reflect concern with MacArthur’s moves, yet there is about them a sense of drift, almost helplessness. Acheson acknowledges in his memoirs, “Not one of us, myself prominently included, served [the President] as he was entitled to be served.”

The Joint Chiefs were cowed by MacArthur. They had opposed CHROMITE and were now reluctant to second-guess the “Sorcerer of Inchon,” as Acheson called him. The JCS did send MacArthur a “request for information” about the gap between the Eighth Army and X Corps, in military etiquette a broad hint from headquarters that the field commander was taking unnecessary chances. But MacArthur merely ignored the request. When the Army Chief of Staff, General J. Lawton Collins, went out to see MacArthur in December, he saluted and said, “Hello, General,” as he stepped off the plane. MacArthur, nominally Collins’s subordinate, just said, “Hello, Joe.”

Acheson was scornful of the Chiefs’ paralysis. But as he later said, he was faced with a dilemma. “Should I sit there uttering amateur questions to the Chiefs? Or go to the President and say, ‘Look, I don’t know anything about soldiering, but for heavens’ sake, this is very bad.’” Acheson dismissed the second alternative because he could not advise the President to do anything. He would thus not be offering a solution, but merely passing the buck, a cardinal sin.

Acheson did go to General Marshall. Almost twenty years later, in 1967, Acheson wrote Marshall’s biographer, Forrest Pogue, to say that he had privately asked General Marshall why, if he was dissatisfied with MacArthur’s strategy, he did not order him to employ a different one, and if he refused, relieve him of command? Marshall replied that he was no longer Army Chief of Staff and that he must bend over backward to maintain a “civilian attitude.” Marshall firmly adhered to a principle first established by Lincoln with Grant in the Civil War: that once a field commander has been assigned a mission “there must be no interference with his method of carrying it out.”

This tradition of noninterference with the theater commander is usually cited by historians as the reason why Washington allowed MacArthur to plunge on heedlessly in the fall of 1950. Yet it did not satisfy Acheson. When he was writing his memoirs in the late sixties, he probed for a better understanding of what, in a letter to Paul Nitze, he called General Marshall’s “curious quiescence.” As Acheson wrote Pogue, Marshall’s hands-off approach “never seemed very sensible to me, especially when MacArthur was violating military discipline and bullying his superiors.” Acheson added, however, “I would rather say nothing than reflect [critically] on General Marshall.”

Marshall was hardly blameless for Washington’s paralysis that fall. Naturally cautious, by now old and careful to conserve his energy, he was not quite up to speed at the Pentagon, which he had taken over only at the end of September. He was made even more circumspect by his personal relationship with MacArthur. At his confirmation hearings, he had been badly abused by congressional fanatics who he knew were in league with MacArthur. If he were to remove MacArthur, he knew, he would set off a congressional fire storm and possibly even precipitate a constitutional crisis.

For more than three decades, ever since MacArthur had been the dashing battlefield commander in World War I and Marshall the brightest staff officer at headquarters, the two men had been rumored to be deadly rivals. Though Marshall did not much like MacArthur, the rumors were way overblown. Still, Marshall felt that he could not afford to show any trace of ill will toward his alleged foe in their official dealings. It was a characteristic response from someone so selfless and stoic, but it did not serve him well. In the fall of 1950, Marshall bent over so far backward to be neutral that he fell down, and abnegated his responsibility.

Marshall’s failure hardly absolves Acheson. The Secretary of State had a policy-making responsibility that transcended military questions. Acheson may not have known much about soldiering, but he knew more about Chinese intentions than Marshall, having been warned by the Indian ambassador to Peking via the British. Later that fall—after disaster struck—Acheson would not hesitate to forcefully and repeatedly override the Pentagon on military matters. But in October and November of 1950, he was strangely paralyzed. His indecision can be explained only by the failure of government among friends.

So taken was Acheson with Marshall, so transfixed by his essential goodness and honor, that Acheson could not see that his former mentor was not up to the challenge of taming MacArthur. In his memoirs, Acheson writes how conscious Marshall was of protocol, refusing to enter rooms before Acheson and always sitting on his left. “To be treated so by a revered and beloved former chief was a harrowing experience,” he records. Acheson goes on to write glowingly that for the first (and last) time the State and Defense departments were able to work as a team. Yet one has the sense that the relationship was almost too cozy; Acheson was too awed and Marshall too polite to disagree with each other.

Lovett was equally blinded by Marshall’s halo. The aging general and his favorite “copilot” had grown so close that aides began to notice that they no longer needed to say much to each other; a few dozen words sufficed to resolve issues that would entangle normal bureaucracies for a day. “They communicated by osmosis,” recalled Felix Larkin, the Pentagon’s chief counsel. If his revered general refused to second-guess MacArthur, Lovett was not about to force the issue. He did not hesitate to entertain the Joint Chiefs with his imitations of MacArthur vainly combing his hair over his bald spot, but he made no effort to persuade them to stop MacArthur’s suicidal trek to the Yalu. Lovett did fret with his friend Acheson over the general’s fool-hardiness, but he did not urge him to intercede with Truman or Marshall. Lovett regarded Acheson with an almost childlike affection. In mid-October, as Washington brooded over MacArthur’s mad march a half a world away, the Deputy Secretary of Defense sent the Secretary of State one of the more peculiar notes ever to travel by interoffice mail: “Dear Stimme, I am tired. Will you please carry me? Gesundheit, Bobchen.”

Ironically, Truman might have been better served if Louis Johnson had not been canned and replaced with Marshall. Had Johnson stuck up for MacArthur, as he surely would have, then Acheson, Lovett, and Harriman might very well have lobbied Truman to have them both fired.

It is likely that Acheson’s independence of judgment was further clouded by his immense loyalty to Truman. The Secretary had become a genuine political liability to his boss and to the Democratic Party. McCarthy was in full cry that fall, stumping on behalf of Republican candidates in the November congressional elections, howling about “the Korea deathtrap we can lay to the doors of the Kremlin and those who opposed rearming, including Acheson.” The Big Lie worked: The Democrats lost six Senate seats and two-thirds of their House majority. Truman was disconsolate; the only time his aide George Elsey recalls seeing him drunk was after the 1950 midterm elections.

Acheson wanted to help Truman. He was well aware of what McCarthy and the whole Republican Party would say if word got out that a striped-pants diplomat had tried to rein in the great Douglas MacArthur. Furthermore, Congress in January was scheduled to begin what was billed as “the Great Debate” over whether to station U.S. troops permanently in Europe. Acheson risked jeopardizing his beloved Western Alliance if he looked like an appeaser in Asia.

At the White House, Harriman was just as sensitive to the politics of the moment, if not more so. Years later, he said about the decision to cross the 38th parallel and conquer all of Korea, “It would have taken a superhuman effort to say no. Psychologically it was almost impossible to not go ahead and complete the job.”

Harriman was an admirer of MacArthur’s boldness. He had, after all, helped sell the general’s daring plan to invade Inchon to the President when the Joint Chiefs were all timidly opposed. Yet, like his friends Lovett and Acheson, he too had qualms about MacArthur’s plunge north. He thought MacArthur’s staff was “third-rate,” he later recalled, and felt that MacArthur’s field commander, Walton Walker, was “incompetent.” On November 24 at a meeting Acheson would later describe as “the last clear chance” to stop MacArthur, Harriman joined the chorus of doubters, worrying aloud that U.S. probes toward the Yalu would provoke the Chinese. At most discussions between the President’s advisers and the top military brass that November, however, Harriman rarely spoke out. Inarticulate and ponderous in debate, Harriman was not much for holding forth at meetings. Furthermore, he felt that he had done all he could by helping to get rid of Louis Johnson and to replace him with Marshall. He saw his own role more as a fixer than a strategist, as the President’s enforcer to make sure that orders were followed and that policy was not disturbed by rivalry and needless bickering. With Johnson gone, and Marshall and Lovett in the saddle, he felt Acheson had no more need for a White House go-between to the Pentagon. He began attending fewer meetings between the two Secretaries.

Like Acheson, he was to regret his failure to loudly speak out against MacArthur’s folly for the rest of his career. Questioned about his role almost two decades later, he fretted, “When I saw those divisions moving up to the Yalu River, I don’t know why I didn’t move.”

On November 24, MacArthur launched what he called his “massive compression envelopment” to “close the vise” around the enemy. He told reporters that he would “have the boys home by Christmas.”

The next day, 300,000 Chinese Communists, hidden in mountain gorges and ravines, exploded around the Eighth Army and X Corps with eerie cymbals, bells, whistles, shrieks, and cries of “Son of a bitch marine we kill! Son of a bitch marine, you die!” With heavy casualties, the American Army turned and fled south.

“We face an entirely new war,” MacArthur cabled Washington. He blamed “conditions beyond control.” “The Chinese have come in with both feet,” Truman said to his shocked advisers. He asked for suggestions. General Marshall admitted that he had no answer. “We want to avoid getting sewed up in Korea,” he said, but “how can we get out with honor?” Acheson, exhausted from passing the dreadful news to congressional leaders, who were less than gracious about it, said he was fearful of a world war. But he was against getting out. “We must find a line we can hold and hold it,” he declared.

Acheson was thunderstruck. He later described what had happened as “the greatest disaster of the Truman Administration, of colossal importance to the history of the U.S.” For him it was a time of great personal crisis. He knew that he had failed his President by not pressing him to stop MacArthur before it was too late. His wife, Alice, later said that she had never seen him so depressed, so fearful for the world. Characteristically he did not reveal his anguish to others. Instead, he kept an even temperament and faced up to the disaster.

Throughout the gloomy meetings of the next few days, Acheson’s voice alone kept up one refrain: the U.S. must not withdraw from Korea. It had to hold. The military was in a state of near panic. MacArthur’s army had suffered one thousand casualties in the first forty-eight hours and was now desperately fighting its way out of the Chinese trap. MacArthur himself had plunged into despair and was warning of the “complete destruction” of his command. To reporters he bitterly blamed Washington for restricting him from bombing Manchuria, “an enormous handicap, without precedent in history.” Lovett read the cables with utter contempt. He told Acheson that MacArthur was “issuing posterity papers” to cover up his blunder. “He’s scared,” said Lovett.

The Joint Chiefs had virtually given up. They told Acheson that they needed to obtain a cease-fire to withdraw U.S. forces. Acheson answered, “There is a danger of our becoming the greatest appeasers of all time if we abandon the Koreans and they are slaughtered; if there is a Dunkirk and we are forced out, it is a disaster, but not a disgraceful one.” General Bradley, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs, wondered mournfully whether “we could come home and just forget the matter.” Acheson snapped, “Certainly not.”

Yet Acheson could not order the Army to stand or die. He confessed to Truman that the U.S. might have to evacuate, or be driven into the sea. “It looks very bad,” the President wrote in his diary.

On the evening of December 3, Acheson, after a day of relentlessly gloomy meetings, was sitting in his office, feeling his strength ebb, when he received a lift from the most unlikely quarter.

Bohlen had watched the debacle from Paris with horror. “MacArthur got caught with his pants down,” he told Cy Sulzberger of The New York Times. The old Russian hand worried that Acheson had no Soviet specialist to advise him during the crisis. So on December 1, he called Kennan by transatlantic phone at his farm in Pennsylvania and urged him to go to Washington and help.

Kennan arrived the next day and was briefed by Jim Webb, Acheson’s number two. The briefing left “substantially no hope that we could retain any position on the peninsula,” Kennan wrote Bohlen. The next evening, after the busy corridors of New State had emptied for the night, Kennan slipped down the hall and stuck his head inside the Secretary of State’s office.

Its occupant, his proud bearing slightly sagging at the end of the another grueling day, rose to greet him. Kennan was shocked to see how exhausted the Secretary looked. Yet Acheson was as ever gracious to the old colleague whose advice he had so often spurned but whose friendship he still valued. “George,” he said with a weary smile, “why don’t you come home and stay with me?”

The two repaired to P Street. Acheson seemed so worn that Kennan did not want to even bring up the war with him. Yet as they settled down with a drink, the shy diplomat found Acheson charming, witty, and quite unbowed. Kennan reflected that he rarely agreed with Acheson anymore, their minds no longer meshed. Yet he could not help but admire his courage.

Inevitably they got to talking about MacArthur’s erratic behavior, the wild and jittery mood of Washington, particularly in Congress and the military. Mrs. Acheson, listening to the two as they conversed across the kitchen table (it was maid’s night out), recalls that Acheson, fidgeting, stood up. He and Kennan went out into the gallery and paced along the long stone passage by the French doors, frosted over this December evening, and into the front parlor. There, beneath the portrait of Bishop Acheson and the photos of Brandeis and Stimson, beneath the Yale rowing cup on the mantel, they talked of the need for staying power, for grit over the long haul.

Before Kennan went to bed that night, he sat down and wrote Acheson a longhand note.

In the morning, Acheson met the plane of Clement Attlee, the Labour Prime Minister, arriving from England in a huff because Truman, at a press conference, had refused to rule out the use of nuclear weapons in Korea. Then he went to his nine-thirty staff meeting. He found there Kennan’s note.

DEAR MR. SECRETARY:

There is one thing I would like to say in continuation of our discussion of yesterday evening. In international, as in private, life what counts most is not really what happens to someone but how he bears what happens to him. For this reason almost everything depends from here on out on the manner in which we Americans bear what is unquestionably a major failure and disaster to our national fortunes. If we accept it with candor, with dignity, with a resolve to absorb its lessons and to make it good by redoubled and determined effort—starting all over again, if necessary, along the pattern of Pearl Harbor—we need lose neither our self-confidence nor our allies nor our power for bargaining, eventually, with the Russians. But if we try to conceal from our own people or from our allies the full measure of our misfortune, or permit ourselves to seek relief in any reactions of bluster or petulance or hysteria, we can easily find this crisis resolving itself into an irreparable deterioration of our world position—and of our confidence in ourselves.

GEORGE KENNAN

Acheson was so moved that he read the note aloud to the small group gathered in his office. Then he spoke for himself. We are being infected with the spirit of defeatism emanating from MacArthur’s headquarters in Tokyo, he said. How, he asked, should we begin to inspire a spirit of candor and redoubled effort?

Dean Rusk, with words that lodged in Acheson’s mind, spoke of the British example, of how they soldiered on through their darkest hour. Rusk suggested that the President fire MacArthur. Kennan, present at the meeting, also spoke of the British rallying in the desert of North Africa in World War II, and suggested that this was a poor time to negotiate with the Soviets, that the U.S. should never negotiate with the Communists from defeat.

The group concluded that they needed to recruit General Marshall as an ally in their effort to stiffen U.S. resolve. Acheson called Marshall and told him that the Korean campaign had been plagued by wild swings between exuberant optimism and despair, that what was needed was “dogged determination.” Rusk and Kennan then went personally to see Marshall to enlist his support for a stand-fast policy. Marshall was quickly persuaded. He responded that MacArthur should be ordered to “find a line he can hold and hold it.” Meanwhile, Lovett arrived from Capitol Hill to report pervasive defeatism in Congress and a growing feeling that the U.S. should pull out. The effect of this news, predictably, was to increase the determination of Acheson’s rump group. By lunch, they had obtained Truman’s vow: “We stay and fight.”

Truman was haunted by broader fears of world war. He wrote in his diary, “It looks like World War III is here. I hope not—but we must meet whatever comes—and we will.” Others shared his dread. The JCS warned all U.S. commanders worldwide that the possibility of general war had “greatly increased.” The night of his long and brooding chat with Kennan, Acheson had gone to bed thinking that he would not be surprised to be awakened by an announcement of global war.

For a moment on the morning of December 6, he thought his nightmare had come true. At 10:30 A.M. Bob Lovett called him from the Pentagon and abruptly informed him in his laconic voice: “When I finish talking to you, you cannot reach me again. All incoming calls will be stopped. A national emergency is about to be proclaimed. We are informed that there is flying over Alaska at the present moment a formation of Russian planes heading southeast. The President wishes the British ambassador to be informed of this and be told that Mr. Attlee should take whatever measures are proper for Mr. Attlee’s safety. I’ve now finished my message and I’m about to ring off.” Acheson cut in. “Now wait a minute, Bob, do you believe this?” “No,” Lovett replied, and hung up. Acheson sat in his office and waited. The Air Force scrambled. A senior official burst in asking permission to telephone his wife to get out of town and wondering if he should begin moving files to the basement. Acheson tried to soothe him. A few minutes later Lovett calmly called back. The radar blips were not Soviet bombers after all. They were flocks of geese.

The attacks on Acheson in Congress reached new extremes. He was vilified not only for his policies, but for his aristocratic hauteur and noble but unfortunate defense of Alger Hiss. On December 15, Republicans in the House voted unanimously and in the Senate by 20 to 5 that Acheson had lost the confidence of the country and should be removed from office.

Outwardly, Acheson was either stoical or mocking about his critics. Archibald MacLeish recalled hearing Acheson whistling bravely while listening to Fulton Lewis’s diatribes against him on the radio. After Bob Taft refused to stand next to Acheson in a procession of Yale trustees, Acheson was greatly amused when the two antagonists were pushed together by accident as they came through an archway into public view, setting off an explosion of flashbulbs. To cabdrivers who would ask “Aren’t you Dean Acheson?” he would reply, “Yes. Do I have to get out?”

Yet Acheson was wounded, his wife recalled, when he was abandoned by his friends in the press. Acheson himself recognized that his relations with the press had deteriorated after he became Secretary. He later described the relationship as “one of baiting them and making up: I thought they were spoiled; they thought I was irritable; we’re both probably right.” He admitted that he tried to “put a little fear of God into the press” and boasted that “you can really get it into them if you snap their heads off.” He succeeded in alienating not just the press-room hacks but the insiders like Reston and Lippmann. Lippmann, who had once nominated Acheson for the Century Club in New York, even called for Acheson’s resignation that fall. Acheson was particularly irked at the Alsop brothers, fellow Grotonians, who had reported what was probably the truth: that Acheson had been slow to rein in MacArthur because he feared being accused of “softness” on Communism.

Acheson did finally lash out at one of his most consistent congressional baiters. During August 1950, Senator Kenneth Wherry, the Nebraska mortician, leaned over a narrow table and started shaking his finger at Acheson during a hearing. Acheson jumped up and shouted at him not to “shake his dirty finger in my face.” Wherry bellowed that he would. “By God you won’t!” roared Acheson. As other senators looked on in amazement, Acheson reared back and started to launch a haymaker punch. Adrian Fisher, the State Department counsel and a former Princeton football player, had to grab the Secretary of State and push him down in his chair. Later, telling of the incident, Acheson tried to make it appear that he had never lost control. As he listened to Wherry fulminate, he said, “I wondered even if I had lost the capacity for rage, a chilling thought. So I began to work up a temper by murmuring hair-raising imprecations. To my delight, I felt the blood rising along the back of my neck and my ears getting hot.” Acheson’s explanation is too arch; one would prefer to believe that he just lost his temper.

As usual, Acheson was protected by devoted friends. Lovett always seemed to be there with some small cheering touch. At Christmas he sent Acheson a bottle of wine with a silly verse, “Some Pomery Rose, to pink your nose, to dull your woes, to make your life cosy.” On January 21, he wrote him more seriously, “I don’t know from what source you draw your courage, but whatever it is, hang on to it—and go on sharing it with the rest of your friends.” To reporters Lovett said of Acheson: “He’s no cookie pusher. He’s a giant.”

In his own mind, Harriman was critical of Acheson. In later years, he would tell his friends that Acheson had foolishly tempted the Kremlin by placing Korea outside the U.S. strategic perimeter. He felt that Acheson’s defense of Alger Hiss had been a blunder that exposed the State Department to right-wing fanaticism. “I think the Secretary of State should turn his back on a man who has been convicted,” Harriman would say to intimates. But to reporters and official Washington that autumn of 1950, Harriman stoutly and loudly defended Acheson. In November, he told a press conference, in his blunt, unartful way, “I don’t believe we have had in our history many Secretaries of State with the guts to deal so forcefully with the issues with which he has been faced.”

Harriman could barely tolerate the men attacking Acheson. After the 1950 elections, Joe Alsop had too much to drink at a dinner party and invited Richard Nixon to a Sunday Night Supper. Fresh from defeating Helen Gahagan Douglas with Red-baiting (“she’s pink right down to her underwear”), Senator Nixon arrived at the Stewart Alsops’ house in a shiny new suit just as another guest, Averell Harriman, was coming through the door. Harriman turned around to walk out. “I will not eat dinner with that man,” he told his hostess. Mrs. Alsop begged him to stay, but at dinner he turned his plate over, switched off his hearing aid, and refused to speak.

Harriman was almost as brusque with Acheson. He knew that many congressmen found Acheson’s bristling Guardsman’s mustache an offensive reminder of class superiority. “Shave it off,” he instructed Acheson, as a sixth former to a fourth former. “You owe it to Truman.” Acheson, ever the vain nonconformist, declined. Privately, Harriman faulted Acheson for not standing up to his political foes. Dining at the Achesons’ in the spring of 1950, Harriman had listened with growing impatience while Acheson outlined a series of speeches that he planned to make on U.S. foreign policy. “Dean,” Harriman finally interrupted, “do you want to write three speeches that can be put into the collected addresses of the great Secretary of State Acheson for future historians to read, or do you want to have some impact on the political situation?” Acheson began to argue with Harriman, until Alice interjected, “I think Averell’s got something.” But Harriman mixed his gruff lectures to his former rowing pupil with moral support. He tried to buck up Acheson by sending him a quote from Swift: “Whomever could make two ears of Corn or two Blades of grass to grow upon a Spit of Ground where only one grew before, would deserve better of Mankind, and do more essential Service to his Country, than the whole Race of Politicians put together.”

Acheson was bemused by Harriman, and deeply grateful to him. A year later, in November of 1951, he went to Harriman’s sixtieth birthday party in Paris, a glittery black-tie affair in Marie’s soignée apartment on the Right Bank. After Harriman had blown out the candles on his cake, Acheson stood up and gave a toast on behalf of “all of us around the table who have come together this evening because we are so fond of Averell.” He recalled first meeting Harriman as a schoolboy at Groton, how awed he had been by him then, how many years they had worked together, how Harriman had become one of the nation’s great public servants. Touched, Harriman rose from his seat and told of how Acheson was the lightest oarsman, at 149 pounds, ever to row for the Yale freshmen, how the two of them had been fired as coaches of the crew, but how they had both survived to row in swifter waters.

Beneath the chandeliers, the small party gathered around a piano and sang sentimental songs while waiters passed around trays of champagne. Lydia Kirk, the wife of Admiral Alan Kirk, old and dear friends of Acheson’s, felt emboldened by the champagne and the intimacy to suggest to Acheson that Averell had always wanted to be Secretary of State, much as he liked Dean. Acheson replied that he had always known this, and that even though they had never been really close friends, Averell had “always been the most loyal friend and faithful servant a Secretary could ever ask for.”

Still reeling from disaster at the Yalu, the Administration was no longer talking about “rolling back” Communism and reuniting Korea as the new year began in January 1951. The U.S. war aim had become the one urged by Kennan and Nitze from the outset: restoration of the status quo at the 38th parallel. Actually, Acheson, Marshall, and Lovett were having difficulty simply persuading the Joint Chiefs that U.S. forces should not quit Korea altogether.

General MacArthur, meanwhile, was preparing for Armageddon. “He simply could not bear to end his career in checkmate,” wrote his biographer, William Manchester. Acheson in his memoirs quoted Euripides: “Whom the gods destroy they first make mad.”

MacArthur wanted to stomp out Communism in the Far East, if not the entire globe, in one last apocalyptic battle. At the end of December, he proposed to the JCS that he blockade the coast of China, destroy China’s industrial capacity with air strikes, and unleash Chiang Kai-shek to attack the mainland. When the Joint Chiefs replied that they were not interested in starting World War III, MacArthur came back complaining that the morale of his troops was suffering and that unless “the extraordinary limitations and conditions imposed” upon him were lifted, “complete destruction” beckoned. The blood, he implied, would be on Washington’s hands. General Marshall dryly observed to Dean Rusk that “when a general complains of the morale of his troops the time has come to look to his own.” Acheson angrily summoned a war council to his house in Georgetown on January 10 and demanded that the military stop bickering and get on with the war.

Fortunately, while Washington and MacArthur talked, General Matthew Ridgway was rallying the tattered U.S. forces in Korea and slowly recapturing lost ground. His plan of attack, code named Operation Killer, was simple and brutal; the objective was not to win territory but to kill as many of the enemy as possible. This attrition strategy relied on superior U.S. firepower; fifteen years later, it would work less well in Vietnam.

In early December, Truman had tried to muzzle MacArthur’s statements to the press by ordering that military commanders should use “extreme caution in public statements.” MacArthur had flouted this directive. He told reporters about the conspiracy against him at the State Department: “This group of Europhiles just will not recognize that it is Asia which has been selected for the test of Communist power and that if all Asia falls Europe will not have a chance.”

He openly criticized the decision to restore the status quo at the 38th parallel. Finally, he intentionally sabotaged peace feelers with a statement denigrating the Chinese as an “exaggerated military power.” If Washington would only remove the “inhibitions” on him, he vowed, China would be “doomed.” The peace initiative was stillborn. The Kremlin called MacArthur a “maniac, the principal culprit, the evil genius” of the war.

Lovett brought the text of MacArthur’s remarks to Acheson’s home at eleven o’clock at night on March 23. Lovett, “usually imperturbable and given to ironic humor under pressure, was angrier than I have ever seen him,” Acheson later wrote. MacArthur, Lovett insisted, should be removed, and removed at once.

Acheson and Truman were almost as angry, but MacArthur was issued more rope with another, more explicit gag order. In fact, he had already sealed his doom. On March 20, he had written the Republican leader of the House, Joseph Martin, that he entirely agreed with the right-wing Republican view that Chiang should be unleashed to open a “second front.” “There is no substitute for victory,” he concluded. The letter was off the record, but the secret was too good to keep. On April 5, Martin read the statement on the floor of the House.

Dean Acheson adored the actress Myrna Loy. He had gone with her and her husband, a State Department official named Howland Sergeant, to a play at the National Theater on the night of April 5 and had returned home in high spirits. He found Lovett again sitting in his living room, with a long hound’s face. “He’s gone too far,” said Lovett. Acheson agreed. Harriman, with his enormous sense of loyalty to the President, was outraged and adamant. MacArthur must be relieved, without delay.

Truman had finally had enough with his megalomaniacal commander. The next night he wrote in his diary, “This looks like the last straw. I’ve come to the conclusion that our Big General in the Far East must be recalled.”

General Marshall, however, balked. He was worried about congressional reaction, about getting military appropriations passed, about his Joint Chiefs. He just could not bring himself to fulfill MacArthur’s paranoid prophecy of three decades that his downfall would come at Marshall’s hand. The old general had the flu. He was wheezing, and his deafness was becoming more noticeable. He wanted more time.

A curtain went down over the White House. The press secretaries were mum, limousines passed back and forth through the private gates to the North Portico, no public schedule was listed for the President. Reporters waiting outside wondered at the crisis.

Over the weekend, Marshall carefully reviewed the cable traffic between MacArthur and Washington. When he finished he was his old decisive self. “We should have fired him two years before,” he told Truman.

MacArthur was fired on Tuesday. Because of a communications snafu, he first heard about it on the radio. The apparent shabbiness of this treatment left a bitter taste that for many welled into a kind of hysteria. Within forty-eight hours, the White House had received 125,000 telegrams: “Impeach the imbecile”; “Impeach the Judas”; “Impeach the bastard who calls himself President”; “Impeach the little ward politician”; “Impeach the red herring.” The Republican right went mad. “This country is in the hands of a secret inner coterie which is directed by agents of the Soviet Union. Our only choice is to impeach President Truman,” said Senator William Jenner of Indiana. “The son of a bitch should be impeached,” snarled McCarthy. He declared that the decision to fire MacArthur had been made by Truman while he was “drunk from Bourbon and Benedictine.”

Around the country, flags flew upside down at half-staff, the President was denounced as “a pig.” A Denver man started a Punch Harry in the Nose Club. Acheson was hung in effigy from streetlamps; posters were painted pleading “God save us from Acheson.”

MacArthur came home to one of the greatest greetings ever given a returning hero. Crowds overwhelmed the police barricades in San Francisco. In Washington, General Marshall dutifully went out to meet MacArthur’s plane. MacArthur, remembering that Marshall preferred to be called by his last name by everyone but his wife, stepped off and said, “Hello, George, how are you?” Before a Joint Session of Congress he attacked appeasement and defeatism, and brought tears with his famous valedictory (“Old soldiers never die, they just fade away. . . .”). “We heard God speak today, God in the flesh, the voice of God!” cried Congressman Dewey Short. At the White House, Truman said to Acheson, “It’s nothing but a bunch of bullshit.”

Acheson called MacArthur “pathetic.” Then he told the story of a family with a beautiful daughter living at the edge of an army camp. The mother worried constantly about her daughter’s virtue and relentlessly badgered her husband with her anxiety. One day the daughter showed up weeping and confessed that the worst had happened, that she was pregnant. The father wiped his brow and declared, “Thank God that’s over.”

It wasn’t quite. Congress launched a massive investigation that the Republicans devoutly hoped would expose the State Department in all its perfidy. Acheson alone testified for eight days. He was asked about everything imaginable, not just about Korea, but Yalta, loans to Mexico to develop oil, soybean speculation by renegade refugees of the Chinese Nationalist regime, and the fact that one of his aides was married to an international oil geologist. He was totally prepared, brilliant, and for once, he held his tongue. One senator complained that Acheson had an unfair advantage because he had greater knowledge of the subject matter. When Acheson was done, on a Saturday, June 9, at 5 P.M., he was asked what he planned to do now. He replied, “I have a plan that will test my capacity for the consumption of alcohol, and if another war erupts before I finish, it must be waged without my services.”

The uproar did not die, but it faded away over the summer. Very shortly, General MacArthur was just an old warrior sitting in his West Point bathrobe in a fancy hotel in New York, dreaming of old battles and the last great one he never got to fight.

With MacArthur out of the way, and Ridgway’s men once more closing in on the 38th parallel, Washington began to search in earnest for a peaceful settlement of the war. Bohlen had begun planting the idea of a cease-fire along the old border with Soviet diplomats in Paris as early as January. By May, Acheson felt that “if hostilities were going to end, this was a good time to see about ending them.”

Kennan had gone back to Princeton before Christmas in a sulk, feeling like a “fifth wheel” and not realizing how much he had helped Acheson with his inspirational letter. Acheson had not forgotten, however, and in May he turned to Kennan again. He knew that Kennan had excellent contacts and was trusted by the Kremlin. He asked Kennan to quietly approach the Soviets and feel them out on a peace offer: a cease-fire along present dispositions, roughly the status quo ante.

Kennan wrote a longhand note to Yakov Malik, the Soviet ambassador to the U.N., asking to see him. Malik promptly invited him to the Soviet mission’s summer compound in Glen Cove, Long Island, on May 31 for lunch. Malik was nervous—he dumped a tray of fruit and wine into his lap—but Kennan, polished and fluent, gingerly laid out the offer and asked that Malik let him know his answer after he had time to consider it, i.e., after he obtained instructions from Moscow. Less than a week later he got his answer: the Soviets wanted a settlement.

The negotiations would drag on for two more years, and thousands more Americans would die in the fitful fighting as both sides maneuvered for better position. Part of the problem was that the U.S. did not recognize the Chinese government, which made diplomatic contact difficult. It was all baffling and frustrating to Acheson. He quoted Bret Harte: “That for ways that are dark/And for tricks that are vain,/ The heathen Chinee is peculiar.”

Academic life suited Kennan. He lived in a comfortable house on a sycamore-lined street in Princeton, students flocked to his lectures, and one of his scholarly works, Russia Leaves the War, would win the Pulitzer Prize. Yet, still in his late forties, he was unable to reconcile himself to leaving public life. He was characteristically ambivalent, unable to commit himself wholly to academe, yet shy of Washington.

Dean Acheson’s respect for Kennan had been partly restored by his stoicism during the grim days of December 1950. Kennan’s deft handling of Malik to launch the Korean peace negotiations further reminded the Secretary of Kennan’s diplomatic skills. When Acheson’s friend Alan Kirk decided to step down as ambassador to the Soviet Union at the end of 1951, Acheson once again looked to Kennan. The Sovietologist could hardly say no. “It was,” he wrote in his memoirs, “a task for which my whole career had prepared me, if it had prepared me for anything at all.”

Kennan, buoyant and curious, had lunch with Acheson in April 1952 to receive instructions. He found the Secretary cordial, but reserved and weary. Kennan left the meeting unsure of his role; further rounds of the State Department and other familiar precincts left him chilled. The spirit of the day was NSC-68. Even his closest friends, he wrote, had been captivated by “the flat and inflexible thinking of the Pentagon.” He began to sense that he was being sent to Moscow to “play a game which I could not possibly win.”

And yet, Kennan could not help harboring a vague sense of hope. Despite his belief that personal diplomacy could do little to sway historical tides, despite his feeling that Russia had never been “a fit ally” for the U.S., he could not help but think that, perhaps, he could make a difference. His return to Russia was “at once a sentimental journey and a diplomatic mission to which he brought a mystical sense of purpose,” recorded Harrison Salisbury, the New York Times correspondent in Moscow who often invited Kennan out to his weekend dacha at Saltykovka.

In his contrary but perhaps insightful way, Kennan sensed that the Soviets, despite their harsh rhetoric, would be receptive to diplomatic overtures to ease tensions and slow the escalating arms race. Brutal, hostile, and paranoid though he was, Stalin was also a pragmatist, Kennan believed. In the opinion of its author, containment had worked: the Soviets had been frozen out of Western Europe, their aggression by proxy met resolutely in Korea. Since Stalin put pragmatism ahead of all else—precedent, ideology, consistency—he would be perfectly willing to abandon belligerence and, without embarrassment, seek peaceful solutions with the U.S. to their mutual problems.

Such was the vision Kennan spun out to Salisbury as he lolled beneath the pines in Saltykovka in the summer of 1952. Kennan hoped for some sign, some small hint from the Kremlin of a change of heart. It was vital, he felt, that someone with particularly sensitive antennae be on hand to catch the first signals. He was prepared, wrote Salisbury, “like a good obstetrician coping with a difficult birth to use the forceps a bit.”

Before he left Washington, he had persuaded the Voice of America to refrain from ad hominem attacks on Stalin and beseeched Henry Luce’s Time and Life to ease up its Kremlin bashing. Yet Kennan gloomily conceded to Salisbury that it was probably too late; that Washington was so deeply committed to stocking its arsenal, rearming Germany, and stiffening its allies that the prospects for diplomacy were slight indeed.

Kennan’s return to Spaso House did not improve his mood. Leaving Annelise, who was about to have a baby, in Bonn, he found the embassy “barnlike, empty, and a little sad.” Servants with whom he had once gotten on pleasantly were now sullen; the outer walls of the grounds were “now floodlit, like those of a prison, and patrolled day and night by armed guards.” He was followed wherever he went, even swimming (the KGB agents would paddle alongside). The “tame Russians,” those with whom he had been allowed to have normal contact in the thirties and forties, “ceased to exist.” At night, he began to wander around the great empty rooms of Spaso House in the darkness, alone. In the dimly lit white ballroom he would play the grand piano or “establish myself in one of the gilded chairs of the several living rooms and read Russian aloud to myself just to indulge my love of the language.” Isolated, uneasy, he began to feel, he wrote home, “like sort of a phantom of the opera.”

Stalin, in his last demented days, had launched a lurid “Hate America” campaign. Moscow was festooned with grotesque propaganda. “Placards portraying hideous spiderlike characters in American military uniform, armed with spray guns and injection needles for bacteriological warfare, stared down at us from every fence throughout the city,” Kennan wrote.

He cabled Acheson that the U.S. was in part to blame for this nadir in the Cold War, that traditional Soviet paranoia had been terribly exacerbated by the growing militarism of the West. The dispatch turned out to be Kennan’s “swan song,” his final dejected piece of reporting on a subject “to which I had now given just twenty-five years of my life.”

In the end, Kennan the dispassionate analyst succumbed to Kennan the tortured man. A small unpleasantry, a minor reminder of his isolation and the Kremlin’s ceaseless paranoia, shattered him.

On a pleasant summer’s day at the end of August, after his family had rejoined him in Moscow, he was watching his two-year-old boy play in the garden. Through the iron fence, some Soviet children smiled at the American child, who “squealed with pleasure” and reached out through the bars to touch them. Guards rushed up and shooed the children away. “Something gave way, at that point,” Kennan recorded, “with the patience I was able to observe in the face of this entire vicious, timid, medieval regime of isolation to which the official foreigner was still subjected.”

Kennan lost his diplomatic poise altogether. Summoned to a meeting of ambassadors in London, depressed that the mood in Western capitals would be no less suspicious than in Moscow, Kennan was silent and withdrawn as he boarded a plane at Vnukovo airport on September 19. Passing through Berlin, he was asked by a reporter at the airport if he had had many social contacts with the Russians. His answer was to compare serving as ambassador to Russia with being interned during World War II in Nazi Germany.

Stalin, not surprisingly, was enraged to be compared to Hitler. The American ambassador had “lied ecstatically,” declared Pravda. Kennan was promptly pronounced persona non grata by the Soviet Union and barred from returning.

Kennan was “deeply shamed and shaken.” The American High Commissioner in Germany, Jack McCloy, found him in a “state of shock.” McCloy was not very sympathetic. He felt that Kennan looked down on him as an amateur. “I thought he was the bright boy and I was anxious to be tutored by him,” McCloy later recalled, but Kennan snubbed him. The moody diplomat turned down the High Commissioner’s offer of a ride from the airport so that he could “think by myself.” McCloy later scoffed, “He didn’t want to be contaminated by conventional policy.” When Kennan was declared PNG by the Soviets, recalled McCloy, “I smiled. Here he was criticizing me for being a lousy diplomat.”

Robert Lovett kept a cartoon in his office at the Pentagon that showed him wearing an aging maiden’s nightgown and mournfully reading three telegrams: “Come be assistant secretary of War. Stimson. Come be under secretary of state. Marshall. Come be deputy secretary of defense. Truman.” The caption read: “Often a bridesmaid, never a bride.”

In 1951, Marshall and Truman finally did right by Lovett and made him Secretary of Defense upon Marshall’s retirement. He was a very good Secretary, one of the few who actually gained some control over the Pentagon bureaucracy. With his great attention to detail, he refused to let the different services simply present him with a request for a lump sum of money every year. He insisted on seeing the figures that demonstrated how they had reached those totals. He was as usual diplomatic about his scrutiny. “We’re not questioning your assumptions,” he told the brass. “We just want to know the basis for your decisions.” Yet he did not hesitate to scratch out the more extravagant items on the wish lists.

He was able to withstand the constant pressure for new high-tech weapons (he thwarted, for example, a “snorkle jeep,” to travel underwater), and forced his way through the layers of obfuscation. “I don’t want a briefing,” he would say. “I just want the facts.” He brought to the job his endearing humor: at one high-level conference, he held up a picture of a melancholy beagle and remarked, “This is exactly how the Secretary of Defense feels this morning.”

Lovett’s greatest capacity as a thinker was to look ahead, to prepare for the next war while the generals were still readying to fight the last one. When the brass had urged more battleships early in World War II, Lovett insisted on bombers. Now that the Pentagon was clamoring for bombers, Lovett wanted to build missiles. He was able to look past the bitter bureaucratic feuding between the Navy (bigger carriers) and the Air Force (more bombers) at what the Russians were doing: building powerful rockets. At his insistence, production on the Atlas intercontinental ballastic missile, abandoned in the late 1940s, was resumed.

Carefully balancing resources and commitments, Lovett resisted potentially costly entanglements. His caution sometimes irked Acheson. When Lovett objected to the cost of advancing oil credits to the shaky government of the Shah during the 1952 Iran crisis,* Acheson scoffed to his aides, “What do you expect from an investment banker?”

Acheson was finding it harder and harder to fend off the McCarthyite attacks on the State Department. In April of 1951, Truman, bending to McCarthyism, had expanded the grounds for dismissal of government employees under the pernicious Loyalty Boards system he had set up back in March of 1947. Now the boards could sack employees on a mere showing of “reasonable doubt” about their loyalty. The burden of proof switched from the government to the employee. Witch-hunts abounded.

One by one, the McCarthyites picked off the old China hands, the State Department experts who had been so enlightened, and so misunderstood, about U.S. policy in the Far East. Acheson had been trying, fitfully, to protect them, but he was running out of room and energy.

He stood up for John Carter Vincent, a gracious Southerner who had warned in 1946 that the Kuomintang was a rat hole for U.S. aid. With the China lobby in hot pursuit, Acheson had tried to hide Vincent in Switzerland, though not as ambassador because the Senate would not confirm him. (Vincent had asked for Czechoslovakia, but he was philosophical about not getting it; he knew he’d be blamed for losing that country too.) McCarthy was so determined to get Vincent that he tried to have him framed as a Communist agent in 1950. Acheson sent Vincent off to Tangier, but that still was not far enough away. A Loyalty Board found “reasonable doubt” about him in 1952. Acheson refused to fire him, but rather set up a commission under retired U.S. Court of Appeals judge Learned Hand (McCloy was a member) to look into the case. Just before leaving the State Department in January 1953, Acheson wrote his successor, John Foster Dulles, “It seemed to me that the opinion of the loyalty review board had passed judgment not on Mr. Vincent’s loyalty but on the soundness of the policy recommendations he had made. If disagreements on policy were to be equated with disloyalty, the Foreign Service would be destroyed.”

Other old China hands received less protection. John Stewart Service had first been shuttled off to Calcutta and then, when McCarthy bore in, sent to the Office of Operating Facilities, where he kept track of typewriters. Smeared with the somewhat contradictory charge that he was a homosexual who had fathered an illegitimate child, he was declared disloyal in late 1952. Acheson let him go. Kennan was unhappy with the decision; he wondered why the Secretary was not helping Service with exculpatory material he knew to be in State Department files. Kennan vainly testified on Service’s behalf, and also went to bat for a PPS expert on China, John Paton Davies, even flying back from Europe at his own expense to appear before Davies’s loyalty hearing. Davies’s crime was doubting Chiang Kai-shek. He was dragged half a dozen times before loyalty boards, cleared each time, and promptly recharged.

By 1952, Acheson was too worn out to make a crusade of defying Joe McCarthy and his ilk. He was himself too much of a target to argue that he was simply trying to uphold procedural safeguards. Korea, the attack of the primitives, a crisis in Iran, Moscow’s Hate America campaign, and a decade of service through hot and cold war had left him drained. He was sick; he had picked up an intestinal amoeba traveling through South America and had chronic diarrhea. He had, at least, not lost his sense of humor. Shortly before he left office, he penciled himself a ditty:

Can’t drive car

Can’t order lunch

Got no program

Don’t have hunch

Got no brains

Got no mem’ry

Call his friends

Tom, Dick, or Henry

Can’t read cables

Can’t write name

As to speeches

’Bout the same