APPEARANCE

The Little Gull (Hydrocoloeus minutus) is the smallest gull in the world, with a wingspan of just 66 cm, and is appreciably smaller than the Black-headed Gull (Chroicocephalus ridibundus; p. 43), a species with which most people are familiar. Adults are readily identified by their small size and dark underwing, which is seen when in flight (Fig. 178). In the breeding season, the black hood of the adult (not dark brown, as in the Black-headed Gull) also aids identification, while the impression of markedly rounded wing-tips is another a useful guide. When flocks are disturbed, they fly in a compact group and in a more erratic manner than other gulls, changing direction in synchrony, more like small waders.

FIG 178. Adult Little Gull in full summer plumage. Note dark underwing. (Ekaterina Chernetsova (Papchinskaya), Wikimedia Commons)

FIG 179. Adult Little Gull in winter plumage. (Alan Dean)

First-year birds have a wing pattern similar to that of Kittiwakes of the same age, but there are minor differences in addition to their smaller size (Fig. 180, right). There is usually a dark cap to the head, which is lacking in the Kittiwake, but the underwing is pale and not dark as in adults.

The Little Gull is a poorly studied species, and several major aspects of its biology remain unresolved.

DISTRIBUTION

The species’ world population is uncertain, with estimates of numbers ranging from 97,000 to 270,000 individuals spread across Asia and Europe, plus a few in North America. It is often said to occur as two (or even three) major populations, which are shown separately on most distribution maps of the species in major works of reference: one in Europe and western Siberia; and one or two in central and eastern Siberia. I have searched in vain for evidence to justify these separate groups, and suspect that there is a continuous distribution in northern Europe and across Siberia, as is the case with the Black-headed Gull (here). This lack of reliable information about the species’ distribution emphasises the uncertain knowledge of its abundance, and there is even uncertainty about its numerical trends within Europe.

FIG 180. Left: first-year Little Gull in flight. Right: first-year Little Gull. (Left, Alan Dean, right, Tony Davison)

Separate from the main distribution, a small group of Little Gulls has started breeding in North America (or perhaps they have been overlooked for many years). The first breeding records were near Lake Ontario in Canada in 1962 and 1963, when three nests were found, and several other Canadian localities have been reported more recently. The first record of breeding in the United States was in 1975 in Wisconsin, when four nests were found in a small colony. The breeding range in North America is not known, and confirmed breeding is restricted to parts of the Great Lakes, southern Minnesota and the Hudson Bay Lowlands of Manitoba and Ontario (Ewins & Weseloh, 1999). These North American birds apparently winter on the east coast of the United States, but the numbers counted wintering there greatly exceed those known to breed in the region. Either larger numbers are breeding in North America and are yet to be discovered, or some individuals are regularly crossing the Atlantic from Europe to winter on the east coast of North America. The only support for the latter possibility was a Little Gull ringed in Sweden as a nestling and recovered dead in Pennsylvania, USA.

BRITISH RECORDS

Much of the early history of the Little Gull in Britain was summarised by Clive Hutchinson and Brian Neath (1978), and I have relied on their information here. Up to the end of the 1930s, the species was infrequently recorded in Britain and Ireland, but since then records have become much more common. The increase began in the late 1940s, when flocks of more than 40 Little Gulls occurred annually in the Firth of Tay and Firth of Forth in Scotland. By the 1960s, larger flocks – some numbering more than 500 birds – occurred there. In England, the increase in numbers occurred later, and it was not until 1955 that the first flocks with numbers in double figures were found on the coast and at an inland reservoir in County Durham. By 1966, flocks of at least 200 were seen at the Hurworth Burn Reservoir on several occasions, with individuals apparently moving between there, a coastal roosting site and, presumably, an unknown feeding area, since there were few, if any, records of individuals feeding. By the end of the decade, appreciable numbers were being recorded on the Lancashire coast and smaller numbers in Wales. Between 1970 and 1972, there were large increases in numbers recorded in many English coastal counties, and in 1972 the first flock was reported in Ireland. By the 1970s, numbers reported in Britain totalled thousands each year, comprising mainly birds visiting coastal areas in the autumn, smaller numbers recorded on passage in the spring, and a few immature birds remaining in Britain throughout the summer.

At this time, the first records were made of Little Gulls passing along the English coast in large numbers – for example, 355 flew east at Dungeness on one day in May 1974, and more than 1,000 per day have passed Flamborough Head on several occasions. Sea-watching for birds was becoming increasingly popular, which may have been the reason for the increase in records. In earlier years, such movements were possibly overlooked, and the immature birds (usually much more numerous than adults) quite likely confused with young Kittiwakes when passing at a distance from the shore.

Currently, hundreds of Little Gulls pass through Britain in the spring on their way to their breeding grounds, while in autumn numbers can exceed a thousand individuals at a single location. For example, 1,900 were recorded at Hornsea Mere in Yorkshire in September 1994, and numbers there reached about 3,000 in 1997. In September 2007, up to 21,000 were reported to be roosting on the lake at night.

There have been, and still are, very few Little Gulls breeding in Norway, Sweden, Denmark and the Netherlands. Finland and the Baltic states are the nearest countries to Britain with sizeable colonies of breeding birds, but even these are too few to explain the large numbers of individuals passing through Britain in autumn, many of which must originate from areas even further to the east. The manyfold increase in numbers visiting Britain in the last 50 years does not appear to be mirrored by large and comparable increases in the world population of Little Gulls. The recent increases in records in Britain and Ireland are far in excess of the undoubted greater number of observers, and in any case this increase would not explain the much larger flocks seen in more recent years. The most likely explanation is that many of the birds currently breeding in Finland and beyond have changed their migration route. There is no knowledge of the route taken by these birds prior to 1950, but they seem to have avoided countries along the western coasts of Europe, including Britain. Perhaps they crossed inland Europe to the eastern end of the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. Judging by the numbers of autumnal sightings in recent years, most of the western portion of the Little Gull population after breeding are now moving through countries in western Europe neighbouring the North Sea, and into the eastern part of the Atlantic Ocean. The cause of this change, if indeed it is taking place, is unknown.

BREEDING IN BRITAIN

It is surprising that, despite the large numbers of Little Gulls now passing through Britain, pairs have nested here on only a few occasions. A search of the literature indicates that at least eight attempts of breeding that involved eggs being laid have been recorded in England, including Suffolk (1966), Cambridgeshire (1975), North Yorkshire (1978), Norfolk (1978 and 2007), Hampshire (1982), Nottinghamshire (1987) and Kent (1987). Some of these records may have been rejected or missed by other authors, while the Hampshire record is not listed in Birds of Hampshire (1993). Breeding was suspected in Scotland in 1988 and 1991, when recently fledged chicks were seen. All the breeding attempts in England failed to hatch any eggs.

In 2016, the first successful nesting by Little Gulls occurred in Scotland at the Loch of Strathbeg RSPB reserve in Aberdeenshire, where a single pair fledged one, or perhaps two, young from eggs laid near a Common Tern (Sterna hirundo) colony. In additional to these records, individuals or pairs have been found in spring in England, Wales and Scotland at potential breeding sites, but without evidence of nesting attempts. While the species often forms small colonies elsewhere, those nesting in England all involved single pairs that attached themselves to Black-headed Gull colonies, and the adults did not return to the same areas in the following year.

The Little Gull usually breeds inland, nesting in freshwater marshes and boggy areas, or on vegetation on or near riverbanks, with the nest built on the ground and usually among vegetation. The usual clutch size is two or three eggs. There is no information on the usual breeding success.

MOVEMENTS

There have been only five ringing recoveries in Britain of Little Gulls marked abroad, with two from Latvia, one from Estonia, one from Sweden and another from Finland. The absence of birds marked further east and found in Britain may reflect the small numbers ringed rather than that those breeding further east do not visit Britain. A hint that Little Gulls from Siberia could visit Britain comes from the recovery in Belgium of a bird marked at Barabinsk, central Siberia (55°21´N, 78°21´E).

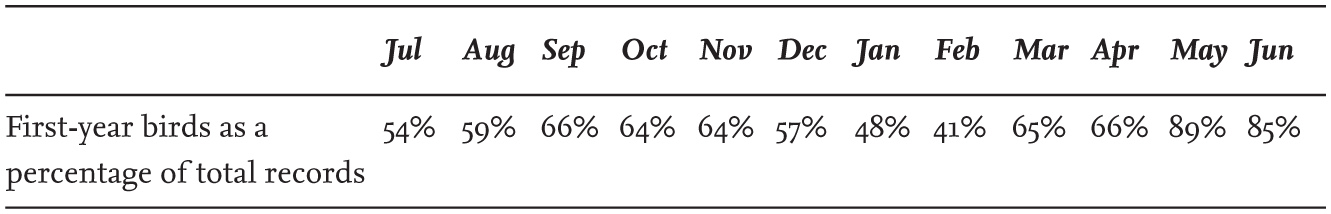

The annual start of the post-breeding dispersal is early compared with other gulls, and a few young of the year have already crossed the North Sea to Britain by the end of July. Numbers of Little Gulls visiting Britain and Ireland up to 1973 were clearly dominated by first-year birds (Table 66). In autumn, it might be expected that less than a third of Little Gulls would be first-years, but 59–66 per cent of those seen between August and November were birds hatched in that year, and so autumn arrivals were heavily biased towards young individuals. This bias persisted throughout the year, and although relatively small numbers of Little Gulls are reported in Britain in winter, about half of those recorded were first-year birds, and again first-year birds dominated sightings in spring and early summer. This suggests that either adults are moving through Britain faster than the younger birds, or that many are using different migration routes. The high proportion of one-year old birds reported in Britain in May and June are presumably individuals spending the summer far from the breeding areas where they were reared.

TABLE 66. The percentage of first-year Little Gulls recorded in Britain and Ireland in each month of the year from 1948 to 1973. The first-year age category runs from July to June of the following year. Based on data reanalysed from Hutchinson & Neath (1978).

However, the more recent data from the West Midlands and inland Hampshire do not support the dominance of sightings of first-year birds other than in August to October (Fig. 181). Records from inland areas show a large peak of adults passing inland through England in April and May, which must involve birds returning to their breeding areas in mainland Europe and beyond. It is interesting to note that no marked peak in numbers occurs in the West Midlands in autumn, but it is evident at inland sites in Hampshire, suggesting that adults are indeed following a different route in the autumn, remaining at sea or near the coast. The differences between the West Midlands data in Fig. 181 (1986–2010) and the national data in Table 66 (1948–73) relate to different periods of time and would appear to reflect real changes in the migration, wintering areas and behaviour of Little Gulls that have resulted in the much larger numbers visiting Britain in recent years.

Most Little Gulls passing through Britain may winter further south, frequenting Spain, Portugal and North Africa, but there is only one ringing recovery to support this. A Little Gull ringed on 6 September 1980 in County Durham was recovered in south-west France on 2 January 1982 at Sainte-Marie-de-Ré (46°09´N, 01°17´W), just north of Bordeaux). However, the numbers seen in Iberia and North Africa in winter are relatively few, and the wintering locations of the missing Little Gulls remain unknown.

FIG 181. The numbers of adult and first-year Little Gulls reported inland in the West Midlands in 1986–2010 and Hampshire in 1951–92. A few birds that were not aged have been omitted, and data for first-year birds runs from July to June. Based on data collated by Alan Dean.

FOOD AND FEEDING

The Little Gull is essentially an insect feeder, consuming aquatic insects taken on the wing at inland marshes and waterbodies, or collected at or just below the water’s surface. The species rarely dives, and small fish are taken only occasionally. On occasions, it has been recorded taking terrestrial insects and worms, and has infrequently been seen following agricultural ploughs, along with Black-headed Gulls.

Questions remain about where individuals feed outside the breeding season. Most autumn records in Britain and Ireland are of birds passing along the coastline, or resting in flocks on the shore or on the edges of reservoirs near the coast, but there are remarkably few records of them feeding. Outside the breeding season the Little Gull becomes a mainly marine species (at least in western Europe), but there is virtually no information on its diet in autumn and winter. Presumably, it consumes small, specialised marine invertebrates that normally float on the sea surface, which also form a key food source for wintering Kittiwakes (here). Small fish are infrequently taken in the breeding areas, but these are unlikely to be consumed regularly at sea.

There is an assumption that Little Gulls outside the breeding season feed offshore, but perhaps within a few kilometres of a coastline to which they return to rest and roost. Some authors have suggested that flocks of Little Gulls seen on the shore have been driven there by strong winds, which prevent them from feeding offshore, but this may be a mistaken interpretation as some of the shore roost sites are visited day after day by resting and preening birds. In 1965, Charles Vaurie suggested that Little Gulls were pelagic, like the Kittiwake and Sabine’s Gull, but I am not aware that birds have ever been seen at a great distance from the coast. It is possible that some individuals do cross the Atlantic, producing the many coastal records in North America, but if this species is truly pelagic and occurs far out into the North Atlantic, presumably birds would have been seen and recorded. Records of seabirds seen in transatlantic journeys on ships in the 1930s to 1950s make no mention of Little Gulls, and this includes seabirds seen during the many Atlantic crossings made by Neal Rankin and Eric Duffey in the 1940s, although these authors do not mention seeing Sabine’s Gull. The biology of the Little Gull is poorly known and much has yet to be revealed – further investigations are clearly needed.