THERE ARE AT LEAST 17 SPECIES of gulls that have not bred in Britain or Ireland but have been recorded here intermittently in varying numbers. Many of these are sufficiently rare for records to be vetted nationally, while others are more frequent and the acceptance of sightings is left to local committees for comment and decision. Some species are at or near the edge of their normal ranges in Britain and Ireland, and occur here occasionally and sometimes in numbers. Other species included in this section are probably only accidental vagrants, occurring far from their normal ranges; they may be individuals displaced by exceptional weather conditions or birds actively pioneering new breeding or wintering areas.

This section includes several species that are difficult to identify in the field and therefore may be under-reported, while others are readily identified but occur infrequently. Many of the British records included have had their identifications critically considered by experts, and while they accept a proportion of the records submitted to them, some are considered insufficiently reliable and are rejected. It is very likely that some genuine records are dismissed because they lack detail, and no doubt a number of possible records are not even submitted for scrutiny. Thus, the total record for any species considered here is an unknown proportion of the actual total occurrences of the gull. Who knows how many rarities reach Britain or Ireland, but are not seen by observers? This number is likely to be large, considering that many accepted records are of birds seen for only one day before they moved away.

The records of several rare species have shown a marked increase in frequency in recent years. These, at least in part, reflect the marked increase of observers in recent years, better knowledge of the key characteristics of some rare species, improved optics and the increased use of photographic evidence in support of sightings. Many published and accepted records from 50 years ago and more were subjected to less vigorous scrutiny, and some have since been rejected. This is evident in the case of the Great Black-headed Gull (Ichthyaetus ichthyaetus), which is now recognised as a species that visited Britain on a single occurrence in 1859. The preserved body of the bird still exists in the Royal Albert Memorial Museum in Exeter, and we must trust that it was actually shot in Britain, as was claimed. Several later records of this species have all been rejected – although it is included by David Bannerman in his Birds of the British Isles (1953) and also here – presumably owing to a lack of details allowing confirmation of identification or doubts about where the specimens were obtained. Species reported less frequently in recent years are likely to be those that are decreasing as visitors to Britain and Ireland, while those with increased records may have become more frequent in their visits or this may simply be a result of the increased numbers of observers today.

Several gull species rarely recorded in Britain and Ireland breed extensively in North America, and it is interesting and surprising that those such as Franklin’s Gull (Leucophaeus pipixcan) and the Laughing Gull (Leucophaeus atricilla) are reported much more frequently here than are gull species that breed much closer, in Spain and southern France, such as Auduoin’s Gull (Ichthyaetus audouinii) and the Slender-billed Gull (Chroicocephalus genei). These differences would appear to be linked to the normal migration or dispersal directions, which take the European breeding individuals south and away from Britain. The Yellow-legged Gull (Larus michahellis; p. 295), American Herring Gull (Larus smithsonianus) and Caspian Gull (Larus cachinnans) have been added to the British list recently, mainly because of changes in taxonomy, and there is no history of earlier records of these species.

Two factors can contribute to confusion over the identification of rare species. First, hybridisation can produce individuals that have characteristics similar to those of other species. Second, some individuals do not show characteristics that allow them to be separated from related species, and this applies both to the immature stages and adults. Adult American Herring Gulls show wing-tip characteristics that overlap with some European Herring Gulls (Larus argentatus); although the possible distinguishing character of a small pale spot on the underside of the tip of the 10th primary has been suggested, its reliability has not been confirmed. A high proportion, but not all, first-year American Herring Gulls show plumage characteristics that differ from European Herring Gulls of similar age reared in Europe. Some Caspian Gulls are identifiable in the field, but other individuals – particularly females – are more difficult to distinguish with certainty from other gull species. Gulls are variable in plumage, and for some species, not every individual is necessarily identifiable in the field. Too little caution is given to the differences in size and structure of males and females of each species, particularly to the size and depth of the bill, which – in males at least – increases in depth for several years. Experience of the observer is important, as is a knowledge of the variability within the commoner species. Hence, numbers of records of Caspian Gulls are reported as ‘possible’, because the occurrence of hybrids and back-crosses is a major problem, producing a range of variation in individuals, which share some of the characteristics of both parent species.

INCREASED RECORDS OF RARE GULLS

Without doubt, the number of capable field observers has increased during the past 55 years, but little attempt has been made to quantify their effect on the numbers of records. The frequency with which Ross’s Gull (Rhodostethia rosea) has been recorded in Britain has not changed since about 1980, and records may even have decreased, while many of the other species show varying increases in sightings in recent years. As a preliminary conclusion, it appears that increased numbers of observers may have been responsible for doubling the number of annual records between 1960 and 2017, and only increases greater than this may reflect genuine increases in the occurrences of each species. The change in numbers of observers is an unexplored field that would produce much valuable information.

Approximate numbers of accepted records of rare species of gulls in Britain are shown in Table 67, with records separated into those up to 1949 and those from 1950 to 2017. The obvious lower numbers of records in the earlier years not only reflects the small number of observers, but also the poorer quality of field guides available at the time to aid identification and the lack of awareness of possible species.

In the species presented below, some of their salient features are mentioned but these are not presented for identification purposes. More extensive descriptions and accounts, such as Collins Bird Guide by Lars Svensson et al. (2010), Peter Grant’s Gulls: A Guide to Identification (1986) or Gulls of Europe, Asia and North America by Klaus Malling Olsen (2004), should be consulted for help with identification. Details of their biology and behaviour can be found in Birds of the Western Palaearctic (Cramp & Simmons, 1983).

TABLE 67. The approximate numbers of accepted records of rare gulls in Britain in two periods up to 2017 and in Ireland up to 2014. Note that these are not necessarily all accepted records. The ‘Comments’ column includes details of years with atypical larger numbers, while dashes indicate that no data are available. Based in part on Reports of Rare Birds published in British Birds.

Problems of identifying individuals in the Herring Gull and Lesser Black-backed Gull complex

Examination of members of the Herring Gull complex captured for ringing or culled reveals the large amount of variation that occurs among individuals breeding at the same site. Often, such variation is not given sufficient consideration when applied to the identification of live gulls in the field.

1. Variation in the Herring Gull. There is considerable variation in the shade of grey of individuals within a given colony and throughout the Herring Gull complex over its wide geographical range. Occasionally, otherwise typical European Herring Gulls with yellow legs are reported, and some breeding birds acquire a yellow tinge to the leg colour at the beginning of each breeding season. Herring Gulls breeding in northern Norway and north-west Russia (Larus argentatus argentatus), and wintering in Britain, are typically larger and have darker mantles than those breeding in Britain (L. a. argenteus), but the variation within each of these subspecies is considerable.

While about 95 per cent of the northern argentatus birds can be identified as such when examined and measured in the hand, a few (mainly females) that were subsequently found breeding within the Arctic Circle in northern Norway failed to be correctly identified on the basis of biometrics, because of their smaller size and overlapping shades of grey on the mantle and wings. The black wing-tip pattern varies considerably, with the so-called thayeri-type pattern occurring in an appreciable minority (Fig. 8), but by no means in all adults breeding in northern Scandinavia and only rarely in birds breeding in Britain.

2. Age and sex effects. The black wing-tip pattern varies with age and is best known in the argenteus subspecies. The white mirrors tend to increase in size between three-, four-, five- and six-year-old individuals. In European Herring Gulls, and possibly in other species, the depth of the bill (particularly in males) continues to increase with age for several years, although that of females changes little.

3. Variation within a species. In Britain, breeding Herring Gulls show considerable variation in the black wing-tip pattern, with differences between individuals in the number of primaries with a black tip and the extent of the white mirror. These differences can occur over quite short distances, such as between the east and west sides of Britain. For example, in one study almost twice the proportion of adults had fewer than six primaries with black pigmentation at or near the tips on the east side of Britain (28 per cent) than those examined on the west side (15 per cent).

4. Variation due to light and direction. In the field, the shade of grey on the mantle can appear to vary with the angles of the bird relative to the directions of light and the observer’s position, depending on whether the bird is seen in sunlight or under cloudy conditions, and the age (wear) of the plumage.

5. Hybrids. These are known to exist between several species of gulls and can lead to incorrect identification. Hybrids often occur more frequently at the edge of the distribution range of a species, where numbers of one of the parent species are low.

RARE VISITORS FROM ARCTIC BREEDING AREAS

Ivory Gull (Pagophila eburnea)

This moderate-sized species has a wingspan of about 1 m. It breeds in colonies, often on cliffs, in the High Arctic at Nunavut, on Ellesmere, Devon, Cornwallis and Baffin islands, in Greenland and Spitsbergen, and also on flat ground (Figs 182 & 183) in northern Russia. During the winter, Ivory Gulls are usually found near areas of open water adjacent to sea ice, and they rarely come as far south as Britain and Ireland. Taxonomically, this species is probably related to Sabine’s Gull (Xema sabini) and Black-legged Kittiwakes (Rissa tridactyla), which also have short legs and a similar build. It is often attracted to seal carcasses and other carrion, including the faeces of mammals. In the breeding season it also feeds on fish and crustaceans, and is known to take eggs of other species.

FIG 182. Large colony of Ivory Gulls (Pagophila eburnea) on Novaya Zemlya. (Fred van Olphen)

FIG 183. Closer view of Ivory Gulls (Pagophila eburnea) on nests on Novaya Zemlya. (Fred van Olphen)

FIG 184. Adult Ivory Gull (Pagophila eburnea) with two chicks near fledging. (Fred van Olphen)

The adult plumage is entirely white, the tip of the bill is yellow and the short legs are black. Adults could be confused with albino individuals of other small gulls, and the black legs would not rule out an albino Kittiwake, but the presence of a partially yellow bill might confirm its identity. Immature birds have some black spots on the tips of the primaries and their coverts, and fewer on the secondary feathers, but most of the wing is pure white, while the front of the head is slightly dark.

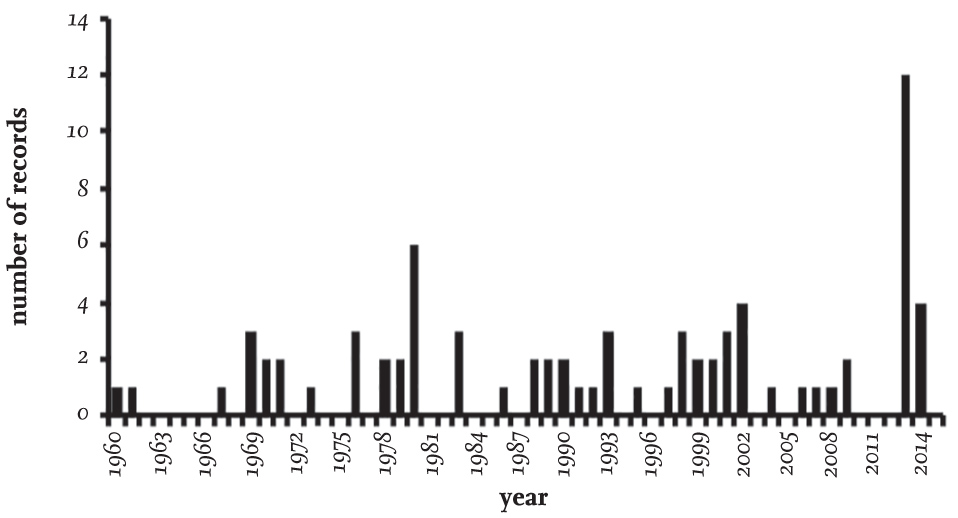

There are at least 150 British records and 19 Irish records of the Ivory Gull, with 12 individuals recorded in 1973. The great majority are from coastal areas around the whole of the British and Irish coastlines, with the peak of records spread from November to January. About a third of these records are birds in adult plumage. The annual records of Ivory Gulls in Britain have increased by about 50 per cent over the last 50 years, but much of this is due to the influx of individuals recorded in 2013 (Fig. 185). If this one value is excluded on the grounds that it was an exceptional year, there is no convincing evidence of a change in numbers recorded over the past 55-year period. If increased numbers of observers have resulted in increased sightings, then the data suggest that the Ivory Gull is actually declining as a visitor to Britain and Ireland.

FIG 185. The number of records of Ivory Gulls (Pagophila eburnea) in Britain from 1960 to 2014. There is no meaningful trend if the peak numbers in 2013 are disregarded. Based on reports of scarce migrant birds in British Bird, Rare Bird Alert and annual county reports.

Ross’s Gull (Rhodostethia rosea)

A small gull with a wingspan of about 75 cm (only slightly larger than the Little Gull, Hydrocoloeus minutus), Ross’s Gull breeds in small colonies on the tundra in the High Arctic of North America, Greenland and north-east Siberia. It usually winters at the edge of the Arctic pack ice and is only occasionally recorded further south. In winter, it could be confused with the Little Gull, but it has longer wings and the tail is pointed rather than forked as in the Little Gull (Figs 186 & 187). In summer, the black neck collar and lack of black on the underwing separate adults from the Little Gull.

FIG 186. Adult Ross’s Gull (Rhodostethia rosea) in winter plumage. (Steven Seal)

FIG 187. First-year Ross’s Gull (Rhodostethia rosea), Vlissingen, Netherlands. (Michael Southcott)

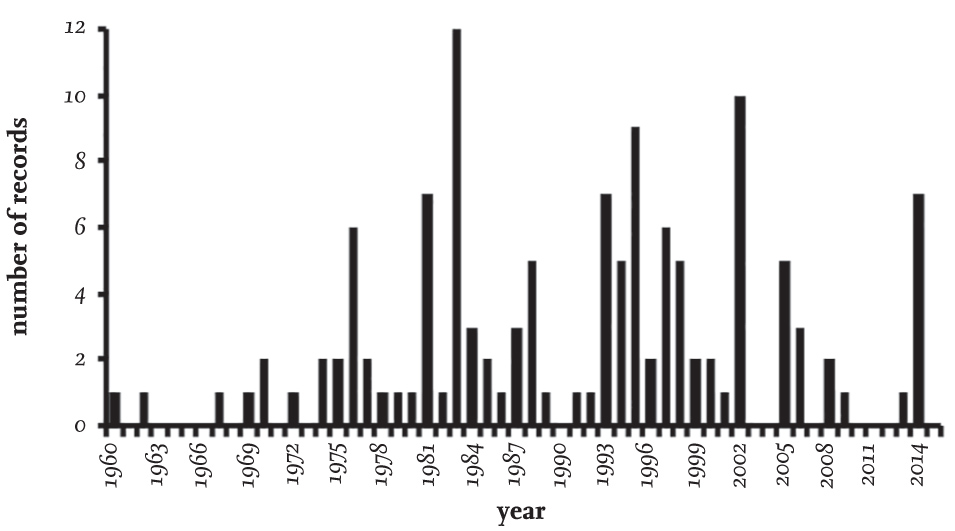

The first British record was a bird shot in Yorkshire in the winter of 1846/47. There is some uncertainty about the exact date but not about the identity of the species, yet this record is often disregarded. The second British record was 90 years later, in Shetland in April 1936, and the third occurrence was not until 1960. More were recorded in every year between 1991 and 2002, and by 2017 a total of 99 records had been accepted for Britain and 22 from Ireland. The pattern of sightings is very different from those of the Ivory Gull (Fig. 185), with records tending to increase up to 1983, and 16 consecutive years (1974–89) with at least one record each year. While numbers fluctuate from year to year, there is only a hint of long-term changes in the annual numbers of records, in that there have been seven years since 2000 when none was recorded (Fig. 188), although a peak of seven records in 2014 now casts doubt on this possible decline and draws attention to the variability in occurrences. Three-quarters of records are of adults, and most occurred in January and February, with almost all found at localities at or near the coast.

FIG 188. The number of records in Britain of Ross’s Gull (Rhodostethia rosea) since 1960. There is no obvious trend, but there are fewer records since 2003 and several years during this period in which no individuals were recorded. Based on reports of scarce migrant birds in British Birds, Rare Bird Alert and annual county reports.

In the breeding season, Ross’s Gulls feed mainly on insects, but there is no reliable information on the food consumed in winter, although it is thought to consist of crustaceans and small fish. Occasionally, individuals have been seen walking over mudflats, presumably searching for small invertebrates.

Glaucous Gull (Larus hyperboreus)

To the Sea, to the Sea! The white gulls are crying,

The wind is blowing, and the white foam is flying.

– J. R. R. Tolkien, The Return of the King (1955)

This large gull, which has a wingspan approaching 1.5 m, is almost the size of the Great Black-backed Gull (Larus marinus). It is an Arctic breeding species with circumpolar distribution. In the Atlantic Ocean and neighbouring areas, the Glaucous Gull breeds in Greenland, Iceland, Jan Mayen, Svalbard, Franz Josef Land and Novaya Zemlya. Its large size and the lack of any black pigment on the wing-tips readily separates it from all other gulls (Fig. 189), with the exception of the smaller Iceland Gull (L. glaucoides; see below). Immature Glaucous Gulls are also pale but slightly less so than adults (Fig. 190).

Some female Glaucous Gulls overlap in size with male Iceland Gulls; correct field identification of these proved difficult in the past, until more detailed differences between the species were recognised. The most obvious difference is the general overall appearance, often referred to as the jizz, but this requires previous experience of the two species. Most Glaucous Gulls are robust and have a similar build to the Great Black-backed Gull, while Iceland Gulls tend to be slimmer, with a build similar to that of the Common Gull (Larus canus). One valuable difference at rest is the small extension of the wing beyond the tail in the Glaucous Gull, and which is appreciably longer in most Iceland Gulls. However, this is not always a good guide because the outer primaries are moulted in autumn. The growth of the new longest primary is often not completed until late October and in some individuals not until the end of December, making this otherwise useful distinction of less value during several months of the year. Another difference is the size of the bill. While this is a useful distinction year-round, there is considerable variation between the sexes and species in terms of the size and depth of the bill, making the separation between female Glaucous and male Iceland gulls less easy. First-year Glaucous Gulls have black on the tip of the bill, while in Iceland Gulls of the same age, the bill is darker for over half of its length. A further identification problem lies with Glaucous Gulls breeding with European Herring Gulls in Iceland and with Glaucous-winged Gulls (Larus glaucescens) in Canada, and producing hybrid individuals with varying amounts of black or grey on the wing-tips.

FIG 189. Near adult Glaucous Gull (Larus hyperboreus). (Mark Leitch)

FIG 190. First-winter Glaucous Gull (Larus hyperboreus). (Alan Dean)

The only British breeding record is of a Glaucous Gull that paired with a Herring Gull annually between 1975 and 1979 in northern Scotland, and successfully reared young in several of these years. The species is not likely to breed regularly in Britain, as there are few records of adults remaining here during the summer months.

The Glaucous Gull’s diet is similar to that of the Great Black-backed Gull (here) and it consumes a wide range of vertebrates and marine invertebrates. It regularly feeds on fish and is a major predator of adult seabirds and their eggs during the breeding season, while also scavenging on carcasses of mammals of all sizes when these are available. The species frequents landfill sites and fish docks in northern areas at other times of year, acting as a scavenger at both locations.

Adults nest in small groups of up to 15 pairs or as single pairs. Nesting areas are often associated with seabird colonies, and the nest is commonly placed on a raised area that gives a good all-round view. The Arctic Fox (Vulpes lagopus) is the main terrestrial predator of the species’ eggs and chicks.

An appreciable proportion of Glaucous Gulls are resident near the breeding areas, and particularly so if there are refuse dumps or commercial fishing activities nearby throughout the year. Others (particularly immature individuals) move south, and those that reach Britain are at the southern edge of their normal winter range and are usually recorded as solitary individuals, although small groups do occur, particularly in Shetland. Individuals occasionally join flocks of other gulls to feed and roost, although the species has been reported feeding alone at landfill sites and leaving when other gulls come in to feed. Inland sightings are now frequently reported in Britain but are rare among the old records. This increase has developed recently, along with the increase in sightings of other large gulls feeding and roosting in winter at inland locations. The numbers of individuals reported in Britain in winter fluctuate markedly from year to year, the differences possibly reflecting variations in breeding success and the feeding conditions further north.

An analysis of records of Glaucous Gulls in the West Midlands made by Alan Dean clearly shows the fluctuation between years (Fig. 191), with a marked peak of records between December and February, and a total absence between April and September (Fig. 192). Numbers of adults never exceeded numbers of immature birds in any year (Fig. 192), and in four years no adults were seen. Most immature birds were in their first year of life, which confirms the general impression that young birds tend to move further south than adults. Most adults did not arrive until December, after completing their primary moult, and first-year birds arrived at the same time despite not moulting. Numbers of Glaucous Gulls reported in the West Midlands vary markedly from year to year, with large numbers in 1986 (32), 1988 (34) and 1989 (41), but only two records in 1996 (Fig. 191). Numbers recorded elsewhere in Britain and Ireland fluctuate similarly from year to year, and on average, several hundred individuals probably occur here in most years. There is no correlation between the numbers of Glaucous Gulls and Iceland Gulls recorded each year in the West Midlands (and elsewhere) (Fig. 193), and presumably, different factors cause the annual fluctuations of these gulls visiting Britain.

FIG 191. The number of Glaucous Gulls (Larus hyperboreus) recorded in the West Midlands, England, each year from 1986 to 2010. Data from Dean (n.d.).

FIG 192. The months in which individual Glaucous Gulls (Larus hyperboreus) of different ages were first recorded in the West Midlands, England, in the period 1986–2010. Based on information collected by Alan Dean (n.d.).

FIG 193. The numbers of Glaucous Gulls (Larus hyperboreus) and Iceland Gulls (L. glaucoides) recorded each year from 1986 to 2010 in the West Midlands, England. There is no correlation between the numbers of the two species seen each year. Data from Dean (n.d.).

Both the Glaucous Gull and Iceland Gull are currently given Amber status as species of conservation concern in Britain on the grounds that only small numbers are reported annually here. The global population shows no evidence of a change in abundance, however, and so the only concern in Britain would seem to be that many birdwatchers do not see these species as often as they would wish.

There are eight records of Glaucous Gulls ringed as nestlings and subsequently recovered in Britain or Ireland in winter. Three were marked on Bear Island (74°N, 19°E), one on Svalbard (76°N, 26°E), three in Iceland and one in Norway (61°N, 34°E). Of these eight recoveries, one was in England, one in Ireland and six in Scotland, confirming the greater frequency of Glaucous Gulls visiting Scotland.

Iceland Gull (Larus glaucoides)

The Iceland Gull is essentially a smaller and less robust version of the Glaucous Gull (see above), with a wingspan of about 1.3 m. It totally lacks black on the wing-tips (Fig. 194). For many years, there was confusion over the identification of these two arctic breeding gulls in the field, but now that better field characteristics have been identified, most individuals can be reliably distinguished. While Glaucous Gulls are large (most the size of Great Black-backed Gulls), Iceland Gulls are more lightly built and usually slightly smaller than Herring Gulls. They have a less substantial bill than Herring Gulls (Fig. 195), a difference comparable to the size difference of the bills of Herring and Common gulls.

While Glaucous Gulls have a circumpolar distribution, the Iceland Gull is more restricted and, despite its name, breeding is mainly limited to Greenland and north-east Canada. It winters in the North Atlantic as far south as Britain, the east coast of Canada and the extreme north-eastern states of the USA.

There have been two ringing recoveries of Iceland Gulls in our region, both marked as nestlings in Greenland and recovered on the east coast of Britain. A second-year was found recently dead at Teesmouth, north-east England, in July, and the other was a first-year bird found on the east coast of Scotland in January.

FIG 194. Second-winter Iceland Gull (Larus glaucoides).(Tony Davison)

FIG 195. Probable second- or third-summer Iceland Gull (Larus glaucoides) standing on an ice floe. (Tony Davison)

Iceland Gulls occur in Britain annually as winter visitors, but in markedly variable numbers – this is evident from the data from the West Midlands (Fig. 196), where most arrive in December or later (Fig. 197). As with Glaucous Gulls, Britain is at the southern edge of their normal winter distribution. The winter of 2009/10 was exceptional, with many more records than in any other year. Most of the birds were immature individuals in their first or second winter, and were not associated with the presence of large numbers of Glaucous Gulls. Large numbers of adults were present in Shetland in the winter of 2011/12, but few immature birds were present. Occasionally, an immature bird spends the summer in Britain.

The Iceland Gull, like all gulls of a similar size, has a widely varied diet that includes the eggs of other bird species and fish. In its wintering areas, scavenging appears to be the main method of feeding, particularly discards from fishing boats and refuse at landfill sites.

The numbers of records of Iceland Gulls have increased dramatically in western Europe in the last 70 years. Much of this increase can be attributed to more numerous and better-informed observers, but it is possible that more birds are now wintering towards the south of the species’ winter range. There is no evidence that the size of the population of the Iceland Gull has changed in its breeding areas and it cannot reasonably be considered a species of conservation concern in Britain.

Thayer’s Gull (Larus thayeri?) and Kumlien’s Gull (Larus glaucoides kumlieni)

Confusion still exists over the taxonomic status of two gulls related to the Iceland Gull, namely Thayer’s Gull and Kumlien’s Gull, which have varying amounts of grey or black on the wing-tips. Some consider the two to be subspecies of the Iceland Gull, while others believe they represent one or even two separate species. Here, the two gulls are considered together, irrespective of their uncertain taxonomic status.

FIG 196. The numbers of individual Iceland Gulls (Larus glaucoides) recorded each year in the West Midlands, England, from 1986 to 2010. Data from Dean (n.d.).

FIG 197. The monthly distribution of arrival dates of Iceland Gulls (Larus glaucoides) of different ages in the West Midlands, England, 1986–2010. Data from Dean (n.d.).

Individuals referred to as Kumlien’s Gull are similar in size to the Iceland Gull, but they have a small amount of darker pigment on the wings (Fig. 198) and breed mainly on Baffin Island, to the west of Greenland. Thayer’s Gull is of a similar size, but has more extensive dark coloration on the wing-tips and nests in the extreme Arctic of Canada (Banks Island, Southampton Island and Baffin Island), as well as in north-west Greenland. Both forms currently present a complex challenge in avian taxonomy. Individuals regarded as Kumlien’s Gull are particularly variable in plumage, more so than in any other gull. They also vary considerably in size, with some males reaching a similar size to Herring Gulls, while extreme females are only a little larger than female Common Gulls. The breeding distribution of Kumlien’s Gull in arctic Canada overlaps slightly with that of Thayer’s Gull, and there is some interbreeding between the two forms. Adding to the confusion, a recent DNA study has suggested that Thayer’s Gull may be more closely related to the Glaucous-winged Gull than to either the Iceland Gull or Kumlien’s Gull. Because of the degree of variation, they are probably the most difficult gulls to separate and identify in the field, particularly when outside their normal ranges. The plumage of Kumlien’s Gull tends to be intermediate between that of the Iceland Gull and Thayer’s Gull in the extent of the grey markings on the wing-tips, ranging from white-winged individuals to others that show much dark pigmentation.

FIG 198. A probable Kumlien’s Gull (Larus glaucoides kumlieni). (John Kemp)

The disagreement about the status of these gulls is considerable and goes back more than a century. A few specimens collected in 1901 on Ellesmere Island in Canada were described by W. S. Brooks in 1915 as a new species, and he named it Thayer’s Gull (Larus thayeri). In 1917, Jonathan Dwight reduced it to a subspecies of the Herring Gull and then later, in 1925, he concluded that Kumlien’s Gulls were hybrids between Thayer’s Gull and the Iceland Gull. In 1933, Percy Taverner claimed that Kumlien’s Gull was a distinct species but in 1937 regarded Thayer’s Gull as a subspecies of the Herring Gull. In 1951, Finn Salomonsen classified Thayer’s Gull as a High Arctic form of the Iceland Gull and indicated that individuals of Kumlien’s Gull were hybrids between the Iceland Gull and Thayer’s Gull. In 1961, A. Macpherson reported that the Herring Gull and Thayer’s Gull did not interbreed in colonies where they occurred together, and so they were not subspecies, and he concluded that Kumlien’s Gull was a subspecies of the Iceland Gull. In 1966, Neil Smith reported that on Baffin Island, Kumlien’s and Thayer’s gulls did not interbreed and so should be regarded as separate species. He went on to claim that by changing the colour of the orbital ring, he had induced mixed pairing of Thayer’s and Glaucous gulls.

In 1968, G. M. Sutton was the first of several authors to publish sceptical reviews of Smith’s 1966 research, but five years later, in 1973 (and perhaps influenced by Smith’s work), the American Ornithologists’ Union (AOU) concluded that Thayer’s Gull was a separate species. However, in 1975 and 1976, B. Knudsen visited the same site used by Smith for his study and found widespread interbreeding between Kumlien’s and Thayer’s gulls, which was confirmed by Snell when he visited the site a few years later. In 1985, A. J. Gaston and R. Decker also confirmed interbreeding between Thayer’s and Kumlien’s gulls, this time on Southampton Island in Hudson Bay.

The British Ornithologists’ Union currently considers Thayer’s Gull and Kumlien’s Gull to be subspecies of the Iceland Gull, referring to them as Larus glaucoides thayeri and Larus glaucoides kumlieni, and suggests that they are part of a gradual change (cline) in characteristics over the geographical range of the Iceland Gull. However, the AOU regarded Thayer’s Gull as a distinct species until it changed its opinion in 2017, and several European authorities, including the Irish Rare Birds Committee, continue to give it species status. In recent years, several birds seen in Britain have been claimed as Thayer’s Gull, and the first accepted record was a bird seen near Oxford in 2007.

There has been a suggestion that Kumlien’s Gull is a series of hybrids between the Iceland Gull and Thayer’s Gull, and that these hybrids are fertile, resulting in the production of many back-crosses, each with different genetic make-up and plumage. Variability of this kind is referred to as a hybrid swarm and could possibly explain the large variation in plumage reported in Kumlien’s Gull, but this interpretation is not currently generally accepted and confusion over taxonomic status continues.

There is a strong desire among many that Thayer’s Gull be regarded as a distinct species, but this is based more on sentiment and a desire for an additional species than on sound scientific evidence. There is still a lack of data, both from the field and from mitochondrial DNA studies. The matter is still not decided, although in 2017 opinion in North America changed and the AOU now considers both Thayer’s and Kumlien’s gulls as forms of the Iceland Gull. To date, no change in their taxonomic status in Europe has occurred. In this book and for convenience, I have placed Thayer’s Gull as a species and, because Kumlien’s Gull is so variable, I have, arbitrarily, considered it as a subspecies of the Iceland Gull.

Birds resembling Thayer’s Gulls regularly winter on the Pacific coast and around the Great Lakes of North America, while Kumlien’s Gulls winter mainly on the east coast of North America. The significance of these differences has yet to be considered.

There are nine accepted Irish records of Thayer’s Gull, with the first seen in February 1990 in County Cork, and all the records are restricted to December to March. Seven of these records were birds in their first year and two were adults. The first accepted British record of Thayer’s Gull was photographed on 6 November 2010 at Pitsea landfill site, Essex, and was an adult. The second accepted record was a first-year bird reported and photographed at Elsham, Lincolnshire, on 3–18 April 2012, while an immature bird stayed on Islay, Scotland, for about eight weeks. Elsewhere in Europe, there are accepted records from Iceland, Norway, Denmark, the Netherlands and Spain, although the only adult among these was seen in Iceland.

In the field, adult Thayer’s Gulls show close similarities with the Herring Gull and males can exceed 1,000 g. As a result, some males are larger than female British Herring Gulls. Most accounts identifying adult Thayer’s Gulls using the wing-tip pattern have been written by Americans and are based on comparisons with the American Herring Gull, which has small white wing mirrors. The situation is different in Europe, however, where patterning on the wing-tips of many members of the Herring Gull subspecies Larus argentatus argentatus, which breeds in northern Norway, show larger white mirrors and have identical or very similar ‘thayeri’ white-and-black wing-tip patterning (see Fig. 8, Chapter 1). Most of the argentatus subspecies of Herring Gulls visiting England are darker than British breeding birds (subspecies argenteus), but not all can be separated by the shade of grey on the wing. Fig. 9 (Chapter 1) shows the wing-tip patterning of an adult Herring Gull captured in north-east England in winter. Was one of these really a Thayer’s Gull that was misidentified? This turned out to be unlikely, as it was later found breeding in Norway.

Adult Thayer’s Gulls within their normal breeding range have been reported with both dark and yellow eyes. The eye colour of Herring Gulls changes with age, but this has not been well investigated in Thayer’s Gull. Leg colour was recorded as bright pink in the first British record of Thayer’s Gull and this may prove to be a good character. Herring Gulls have pinkish-grey legs, but the colour intensity changes as the breeding season approaches. It may simply be the case that some individuals cannot be identified in the field. The identification of Thayer’s Gull outside of its usual range is made difficult owing to the presence of similar-looking hybrids, involving Herring Gulls, American Herring Gulls or Glaucous-winged Gulls as one of the parents, mating with Iceland Gulls.

The difficult identification of Kumlien’s Gull and its dubious status caused the British Birds Rarities Committee to cease considering records after 1998. As result, the numbers of records of this species in Britain is uncertain but there have been at least 51 possible sightings.

Sabine’s Gull (Xema sabini)

Sabine’s Gull is a small gull, similar in size to the Black-headed Gull (Chroicocephalus ridibundus), and has a circumpolar distribution, breeding in the High Arctic tundra of Siberia, northern Greenland, Alaska and Canada. A few authorities still place it in the genus Larus, but its closest relation may be the Ivory Gull.

The species has a contrasting patterned wing plumage (Fig. 199). Adults in the breeding season have a dark grey hood, which in some individuals is retained well into the autumn (Fig. 200). Outside the breeding season it is a pelagic species, remaining well offshore and usually out of view of land-based observers unless driven ashore by strong winds. In winter plumage, the adults seem Kittiwake-like, but with more black on the outer leading edge of the wing and a forked tail that, surprisingly, is often not obvious when the bird is in flight. Immature birds also possess a contrasting wing pattern similar to Kittiwakes of the same age, but there is greater contrast between light and dark shades, and they have a brown-grey mantle, neck and hood (Figs 201 & 202).

FIG 199. Adult Sabine’s Gull (Xema sabini) in flight and in summer plumage. (Phil Jones)

FIG 200. Adult Sabine’s Gull (Xema sabini) in summer plumage. (Steven Seal)

Many Sabine’s Gulls winter south of the equator in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. The migration of this gull has been investigated using geolocators on adult birds breeding in north-east Greenland in 2007. Ten of these birds were recovered at the same colony in the following year, which allowed the movement of these individuals to be followed for a full year. Autumn migration took the birds from Greenland towards Britain and the Bay of Biscay, where most had arrived by the end of August and remained for an average of 45 days. Most left this staging area by mid-October and moved south, close to the west coast of Africa, to winter off the south-west coast of South Africa in a productive area called the Benguela Upwelling. They remained there for about 150 days and did not start their return migration until mid-April, when they moved rapidly to a staging area off the west coasts of Morocco, Mauritania and Senegal, where they remained for about 19 days. They then moved north through the middle of the North Atlantic, well away from the coastline of Europe, to return to their breeding areas in Greenland. The migration covered more than 30,000 km in a year.

FIG 201. First-year Sabine’s Gull (Xema sabini). (Steven Seal)

The timing of the Sabine’s Gull migration agrees closely with the records of birds seen annually but in variable numbers in Britain, where most are recorded between September and November. In contrast, few are recorded in Europe on their springtime return migration to the Arctic, which is rapid and direct, with most individuals remaining far from Britain. This migration pattern probably accounts for many of the records being reported from the western side of Britain and Ireland, and the considerable year-to-year variation in the number of records.

Sabine’s Gulls are subject to occasional wrecks, when numbers of individuals are driven onto the European coast as a result of strong winds associated with intense atmospheric depressions. In these circumstances, some are forced inland. Such events have been studied in detail by Norman Elkins and Pierre Yesou (1998), and the most noteworthy involved more than 300 individuals reported in Britain on 16 October 1987 and successive days, with almost all the reports from the region extending from Dorset to Essex. More frequent autumn wrecks have been reported from France. The largest there occurred in the Vendée region in 1993, when more than 1,600 individuals were reported inland, yet few were seen in England at the same time. Another wreck occurred in 1995, with hundreds recorded in France. In the autumn of 1997, about 1,000 Sabine’s Gulls were seen passing south off the coast of Ireland, with 347 recorded from the coast of County Kerry on 29 August and unusually high numbers passing south through the Strait of Dover in October. Surprisingly, most of the individuals reported were full adults, with birds that had hatched that year forming only a few percent of those seen. Such events, but on a smaller scale, have occurred in other years, and the greater frequency in France than in Britain suggests that many birds are aggregating and feeding off the coast south of Brittany in autumn, rather than off Britain and Ireland. Franklin’s Gull (here) and Sabine’s Gull are the only gull species that make regular and extensive trans-equatorial migrations.

FIG 202. First-year Sabine’s Gull (Xema sabini). Note the tail does not always look forked. (Dave Turner)

Sabine’s Gulls nest on flat ground, usually next to water and sometimes in or adjacent to Arctic Tern (Sterna paradisaea) colonies. In the breeding season, the gulls feed on spiders and insects, which are taken by searching plover-like on mud and soil rather than catching them on the wing. Details of the species’ diet are lacking, and the suggestion that they feed regularly on tiny springtails (Collembola) seems unlikely, as is a report that they consume small birds. The suggestion that their food away from breeding areas often includes jellyfish has been repeated by several authors, but apparently without new and additional information confirming the original report. As with the Kittiwake (here), the identity of food consumed by Sabine’s Gulls while they are pelagic has not been investigated, but it must differ markedly from that consumed during the breeding season.

RARE VISITORS FROM NORTH AMERICA

Laughing Gull (Leucophaeus atricilla)

The Laughing Gull is a medium-sized gull with a wingspan of about 1 m. It forms large colonies on coastal marshes and islands along the eastern seaboard of America, from Nova Scotia in the north to Florida, the Caribbean and Venezuela in the south. The northern breeders winter within the southern breeding range of the species, while those birds that breed in more southern areas are mainly sedentary.

FIG 203. Adult Laughing Gulls (Leucophaeus atricilla) in summer plumage. (Phil Jones)

FIG 204. First-year Laughing Gull (Leucophaeus atricilla) in flight. (Steven Seal)

The wings of the Laughing Gull are a darker grey than those of Common and Black-headed gulls, which are of a similar overall size. In addition, adults have only small white mirrors on the black wing-tips, and these are totally absent in immature birds. The legs and bill are long and red. Adults have a black hood in the breeding season (Fig. 203), but this is lost in winter, the season during which most sightings are recorded in Britain. The Laughing Gull can be confused with the smaller Franklin’s Gull, which also has dark grey wings, but that species has large white wing-tip mirrors and a shorter bill. First-winter Laughing Gulls have a dusky grey breast and flanks, and all-dark primaries (Fig. 204).

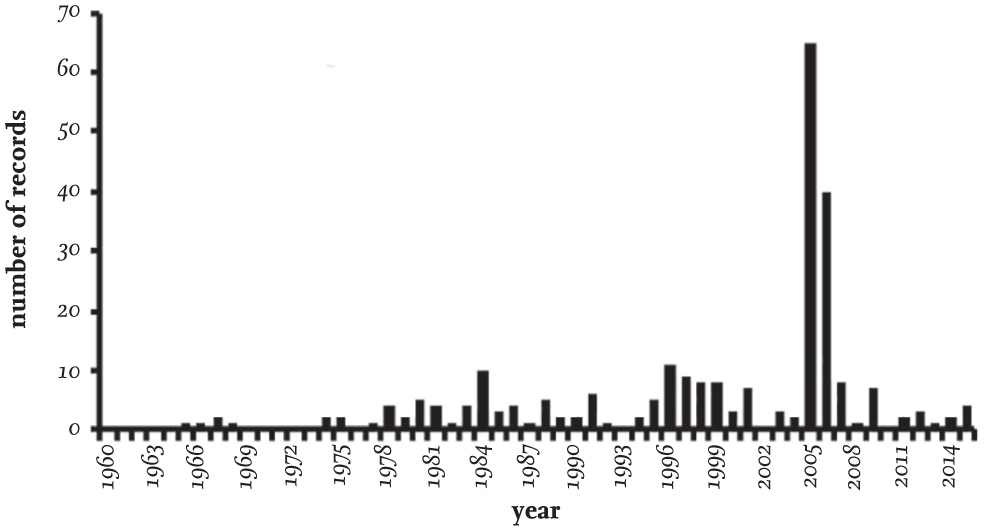

The first record of a Laughing Gull in Britain was in Sussex in 1923 and the second was not until 1950, after which it occurred more frequently. Sightings have been almost annual since 1974, and at least 200 have been recorded in Britain and 43 in Ireland. A large influx of at least 63 individuals occurred late in 2005 and 26 more were reported early in 2006, but there is no evidence that any of these birds stayed to breed. The peak of records occurs in November and about 40 per cent of those recorded have been adults. Numbers of Laughing Gull records have remained low in most years, with no indication of an increase recently apart from the one exceptional influx (Fig. 205). The species is increasing in North America, and the number of European records since 1974 probably reflects both this and the increase in observers.

The Laughing Gull consumes a wide range of foods, including fish and marine invertebrates. It also is attracted to food produced by human activities at beaches, car parks, sports areas and landfill sites, and it frequently engages in kleptoparasitism.

FIG 205. The number of records of Laughing Gulls (Leucophaeus atricilla) in Britain and Ireland from 1960 to 2015. Note the exceptional numbers recorded in the winter of 2005/06. Based on Rare Bird Alert reports and other sources.

Bonaparte’s Gull (Chroicocephalus philadelphia)

This is a small gull, just a little larger than the Little Gull, with a wingspan of about 80 cm. Its numbers are believed to be increasing on its breeding grounds, which extend across North America, from Alaska through Canada as far as James Bay. Most pairs nest about 3 m above the ground in trees growing on islands and at the edges of bogs, marshes and ponds, but they avoid densely forested areas. The usual clutch is three eggs. In winter, Bonaparte’s Gull moves south to ice-free rivers and lakes along both the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of North America, reaching the Caribbean and Mexico.

This species closely resembles a Black-headed Gull, but adults show a lighter underwing when in flight (Fig. 206). In summer plumage, it has a black head (not chocolate brown, as in the Black-headed Gull). The legs are pink. First-year birds are very similar to Black-headed Gulls of the same age, with minor differences in the distribution of dark feathers on the primary coverts in the wing (Fig. 207). In individuals of all age classes, the small bill is mainly, or totally, black.

FIG 206. Adult Bonaparte’s Gull (Chroicocephalus philadelphia) in flight. (Tony Davison)

FIG 207. First-year Bonaparte’s Gull (Chroicocephalus philadelphia). (Nicholas Aebischer)

The first record of a Bonaparte’s Gull in Britain was a bird collected on Loch Lomond in Scotland in 1850. Over the next 100 years, records increased to just eight but then began to increase markedly. By the end of 2017, there had been 245 accepted records in Britain and, by 2014, 76 in Ireland. In 38 of the 40 years since 1975, at least one sighting has been recorded (Fig. 208) and an appreciable proportion of these were found inland. The peak of records is from March to May, and more than half of those seen were birds in full adult plumage. The pattern of numbers recorded since 1960 contrasts with that of the Laughing Gull (Fig. 205), another species that breeds in North America. The magnitude of the increase in Bonaparte’s Gull records is so large that it cannot be explained by the increase in numbers of observers in recent years, and so must indicate a major increase in the numbers of birds visiting Britain and Ireland. In 2017, a pair bred in Iceland, and with increasing numbers occurring on the east side of the Atlantic, there is a possibility that breeding may occur in Europe, particularly if the present trend continues.

FIG 208. The number of British records of Bonaparte’s Gull (Chroicocephalus philadelphia), 1960 to 2015, showing a marked increase in records starting about 1986. A smoothed trend line is indicated. Based on reports of scarce migrant birds in British Birds, Rare Bird Alert and annual county reports.

Insects make up the majority of food consumed by Bonaparte’s Gulls during the breeding season, while in winter a wide range of invertebrates is consumed. Some feed on the ground on mudflats.

Franklin’s Gull (Leucophaeus pipixcan)

Franklin’s Gull is a North American gull that is similar in size to the Black-headed Gull and has a black hood in the breeding season, when it resembles the Little Gull or a small Laughing Gull (Fig. 209). It has more black on the wing-tips than the Little Gull and larger white wing mirrors when compared with adult Laughing Gulls. All plumage stages are similar to those of the Laughing Gull, but Franklin’s Gull has an appreciably shorter bill, which, like the legs, is bright red. Because of the early total moult of the primary feathers (see below), one-year-old birds closely resemble the adults (Fig. 210).

The species commonly breeds inland in colonies that can involve hundreds of pairs, and is found locally throughout the prairie provinces of western Canada and as far east as the Great Lakes and into the USA. It is the most abundant inland breeding gull in North America, and in this respect is the equivalent of the Black-headed Gull in Europe. It nests on the ground and on floating vegetation in marshes and along inland lakes; the usual clutch is three eggs.

FIG 209. Adult Franklin’s Gull (Leucophaeus pipixcan) searching for marine invertebrates on tidal mudflats while wintering in South America. Note the conspicuous wing mirrors and partially black head. (Norman Deans van Swelm)

FIG 210. First-year Franklin’s Gull (Leucophaeus pipixcan) with a partially darkened head. Note the lack of wing mirrors. (Norman Deans van Swelm)

Franklin’s Gull winters along the Pacific coast of South America, from Guatemala to Chile. It makes a trans-equatorial migration, mainly avoiding the Atlantic Ocean coast of North America, which probably explains why few reach the eastern side of the Atlantic to Britain and Ireland.

The first record in Britain was as recent as 1970, when two individuals were found in Hampshire. A further 75 individuals were recorded in Britain up to 2017 and 17 more from Ireland by 2014. There was a maximum of 12 recorded in any one year in Britain (Fig. 211). The occurrences are spread widely throughout the year, with the fewest in September, and records peaked in 2005 and 2006. About 40 per cent of sightings are of adults.

FIG 211. The number of records of Franklin’s Gull (Leucophaeus pipixcan) in Britain since the species was first reported in 1970. A smoothed trend line is shown. Based on reports of scarce migrant birds in British Birds, Rare Bird Alert and annual county reports.

Franklin’s Gull is unique among gulls in that it moults its primary feathers twice each year and there are records of individuals in primary moult in every month of the year. If the existing data are correctly interpreted, the usual post-breeding moult of the primaries is slow and is spread over about four months, ending in late October, and so includes the period of migration to the species’ wintering areas in South America. A further moult of the primaries starts within a month of the completion of the post-breeding primary moult, and again it is in progress during migration as the birds return to the northern hemisphere, apparently being completed before most individuals begin nesting. Some first-time breeders retain the old outer primaries while breeding. There is considerable variation in the state of moult between individuals that have been collected on a similar date, perhaps reflecting an age difference.

It is not currently understood why Franklin’s Gulls require two primary moults each year. A second moult of the primaries is a considerable cost in terms of energy, and it is strange that moults are apparently in progress during both annual migrations. Whether the moult is suspended during the actual migration has not been determined. There is a need for more data from additional specimens, particularly from the wintering areas and during migration, and a comparison made with the unusual and complex primary moult in the Common Tern (Sterna hirundo), which has a similar migration pattern to Franklin’s Gull that also involves crossing the equator. The only suggestion that has been offered so far as to why there are two primary moults each year is that the feathers might deteriorate faster in the warmer weather and high solar radiation experienced by individuals throughout the year. However, this requires supporting evidence, as a double moult does not occur in those tern species whose annual migration also involves moving between the northern and southern hemispheres.

The diet of the Franklin’s Gull includes a broad spectrum of food during the breeding season, including many freshwater insects and small fish. It some areas it frequently follows ploughs on farmland to catch the worms, insects and mice that are disturbed, but it rarely attends landfill sites. It is assumed that it takes similar food during its migrations and in its wintering areas, where it searches for marine invertebrates on mudflats and may consume fish more frequently.

Ring-billed Gull (Larus delawarensis)

Ring-billed Gulls breed only in North America and have increased markedly in numbers following persecution in the nineteenth century, much as the Herring Gull has done in Britain (here). It is probably the most abundant gull in North America, breeding mainly inland in Canada and the northern part of the United States, particularly around the Great Lakes. The species nests in both small and large colonies, some of which can reach several thousand pairs, on open, bare ground with scattered vegetation beside lakes, along rivers and on the coast. The typical clutch is three eggs. The gulls normally winter along the whole of the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of North America and around the Great Lakes.

The adult Ring-billed Gull looks like a slightly large Common Gull, but differs in having a broad black band across the whole of the bill near the tip, while the Common Gull’s bill is entirely yellow in the summer and has an indistinct black band in winter (Fig. 212). The adult Ring-billed Gull has a yellow iris, while the Common Gull has a dark brown eye. Immature individuals are very similar to Common Gulls of the same age, and both have dark-tipped bills and a dark eye, but there are minor differences, such as the shade of grey on the wings and the pale legs. The Ring-billed Gull tends to have a stouter bill than the Common Gull, but the sex difference in bill depth makes this an unreliable character, with male Common Gulls having similar-shaped bills to female Ring-billed Gulls.

The Ring-billed Gull was first recorded in Europe when two individuals marked as nestlings in North America were recovered in Spain, one in 1951 and the second in 1965. The first confirmed British sighting was in 1973, when two were present in Swansea Bay, Wales, and the first Irish record was reported in 1979. Thereafter, there have been many records in Britain, with at least 11 in 1980, 16 in 1981, 31 in 1982, 27 in 1983 and 65 in 1985, with a peak of 103 in 1992 (Fig. 213). Most birds were seen between November and April. A nestling ringed in June 1980 at Lake Champlain, New York state, USA, was found dead at Doochary, County Donegal, on 28 December 1981.

FIG 212. Adult Ring-billed Gull (Larus delawarensis). (Tony Davison)

The large numbers of recent records arise, in part, when observers become alerted to the possibility of the species’ presence in Europe. There was a large influx in the 1980s and early 1990s, with some birds staying on eastern side of the Atlantic for several years and raising the possibility that they might remain for many years. One bird returned annually to Gosport in Hampshire for 12 successive winters, and another visited Westcliff-on-Sea in Essex for at least eight winters, but where they spent each summer is unknown. The species continues to be recorded annually in Britain and Ireland, but in lower numbers than in the 1980s. Between 2004 and 2017, the numbers of adults recorded in Britain have declined, with an average of about 15 records each year. In contrast, numbers of first-year birds have declined less markedly, and because of their age, these must be new arrivals from North America each year. Since 2010, first-years have formed the majority of records in Britain (Fig. 214).

FIG 213. The annual number of sightings of (a) first-year and (b) older Ring-billed Gulls (Larus delawarensis) in Britain from 1990 to 2015. Redrawn from White & Kehoe (2017).

FIG 214. The percentage of first-year Ring-billed Gulls (Larus delawarensis) among the annual records in Britain, 1990–2015. A trend line has been fitted to the data points. Redrawn from White & Kehoe (2017).

There are about 15 records each year from Ireland and many records from countries along the west coast of Europe, extending from Spitsbergen to Spain, and the Ring-billed Gull is now by far the most frequently recorded North American gull visiting Europe. It is also the most likely North American species to colonise Europe. So far, no breeding records of pairs of Ring-billed Gulls have been reported in Europe, but in 2004 one adult was seen paired with a Common Gull in a colony in County Down, Northern Ireland, and reared a hybrid chick that year (this was ringed as a Common Gull chick, but when seen as an adult in 2008, its plumage suggested that it was a hybrid). In 2009 and 2014 a Ring-billed Gull was present at a nest in a Common Gull colony in Scotland, but its mate was not seen. In 2016 it was paired with a Common Gull and shared incubation of two eggs at the same colony. Despite this, from 2000–16 there have been a reduced number of sightings of this species in Europe, and the likelihood of this species breeding regularly in Europe has decreased for the time being.

Records of Ring-billed Gulls have become so extensive in Europe that there is a possibility that a change occurred in the migration pattern of part of the population during the 1980s, which resulted in small numbers of adults regularly wintering in Europe. The occurrence of the same individuals wintering at the same locations in different years suggests that either these birds remained in Europe, or that they were making a regular annual migration and deliberately crossing the Atlantic to winter in Britain and other countries along the western coast of Europe. If this is the case, the recent decline of records of adults would suggest that those individuals involved are dying and are not being replaced.

The food of this species is similar to that of Common Gulls, comprising mainly invertebrates and occasional fish caught in intertidal areas or on pastures. In addition, the birds frequently obtain food rejected or dropped by humans at car parks in shopping complexes and near fast-food stores. Individuals in North America have been reported feeding on berries during the autumn and winter. Ring-billed Gulls do not appear to visit landfill sites in Britain, although large numbers frequently do so in North America.

Glaucous-winged Gull (Larus glaucescens)

Adult Glaucous-winged Gulls resemble a faded version of the Herring Gull, with the wing-tips reduced to shades of grey rather than being black (Fig. 215). The breeding range of this species extends around the North Pacific Ocean, from the Commander Islands in the east, through the Aleutians, the Pribilofs and the south Bering Sea, to Alaska and south-east to Oregon in the west. It winters from the Bering Sea to northern Japan and Baja California.

Currently, there are only three British and one Irish record of the species, which breeds far from Europe. The first record in Britain was in December 2006, when a third-winter bird was trapped and ringed at Gloucester landfill site. This individual was subsequently seen in March 2007 in Carmarthen, Wales, and then returned to Gloucester, and was last recorded at Beddington, London, in April of that year. A second bird was reported in north-east England in 2008, and a third individual was recorded in 2016 in County Cork, Ireland. In 2017 an adult was found on Fair Isle. There have also been two previous records of Glaucous-winged Gulls in the Western Palaearctic, one from the Canary Islands and the other from Morocco.

FIG 215. Glaucous-winged Gull (Larus glaucescens). Note the dark grey primaries. (Dick Daniels, carolinabirds.org)

Unfortunately, the Glaucous-winged Gull frequently forms mixed breeding pairs with other species of gulls, and hybrids have been reported with the Western Gull (Larus occidentalis), Slaty-backed Gull (L. schistisagus) and American Herring Gull, while some Glaucous Gull × American Herring Gull and Glaucous Gull × Herring Gull hybrids have occurred in North America and Iceland. All of these hybrids can look very like Glaucous-winged Gulls, and it is often difficult – if not impossible – to be sure that individuals found outside their normal range are not hybrids.

American Herring Gull (Larus smithsonianus)

Herring Gulls breeding in North America have long been regarded as a subspecies of the Herring Gulls that breed in Europe (Larus argentatus smithsonianus), and the American Ornithological Society still treats them as such. However, in 2007 the British Ornithological Union changed its classification and raised the American Herring Gull to full species status.

The American Herring Gull breeds in Canada, from the west coast to Baffin Island and Newfoundland, and in the USA in Alaska, the Great Lakes and the northern part of the Atlantic coastline. Dispersal in winter is limited, with some individuals moving only to the southern states of the USA or to Mexico, while others remain in their breeding areas.

FIG 216. First-year American Herring Gull (Larus smithsonianus). (Phil Jones)

American Herring Gulls are more readily identified and separated from their European equivalent in their first year of life, and they tend to be darker than European birds of the same age. In addition, they have virtually no white on the tail, while the rump is dark and shows less contrast (Fig. 216). The head tends to be lighter, with a clear demarcation from the darker upper breast. Only 3 per cent of European records of American Herring Gulls to date involve adults and 70 per cent are first-winter birds, suggesting that either older birds are more difficult to identify outside of their normal range or that young birds disperse further.

The first record in Britain was in 1994 on Merseyside, and by 2017 records had increased to 33, while 96 sightings have been reported in Ireland. The records are mainly between December and March, and most are from the Irish coast and the west coast of England. There is only a single record on the east coast of England. Records peaked between 1996 to 2008. To date, there have been no ringing recoveries of an American Herring Gull in Europe, so movements to Europe cannot be confirmed. The nearest was an individual captured in the Atlantic Ocean 400 km off the coast of Spain in November 1937.

A large adult Herring Gull recorded in May 2008 at Chew Reservoir in the Peak District was repeatedly seen by gull experts Andy Davis and Keith Vinicombe, who ‘confirmed beyond any reasonable doubt that the bird was an American Herring Gull’ (Davis & Vinicombe, 2008). While preening, the bird dropped a feather, which was recovered and sent for DNA analysis to Gareth Jones; the subsequent analysis confirmed that the bird was not an American Herring Gull after all.

The problem with the Chew Reservoir sighting and other similar cases is that the observers and those suggesting key characters have often failed to appreciate the variation that exists within European Herring Gulls, American Herring Gulls and hybrid gulls. Adult American Herring Gulls are unlikely to be safely distinguished in the field in Europe unless new and infallible characters are identified, while immature individuals with characteristics believed to be the American species may be only a small proportion of those moving to Europe from North America. On the other hand, those reportedly identified may not be actually reared in America. As of now, the best that can currently be achieved is to qualify claims of American Herring Gulls recorded in Europe with the word ‘probably’ unless these sightings involve ringed individuals.

RARE VISITORS FROM SOUTHERN EUROPE AND NORTH AFRICA

Azores Herring Gull or Azorean Yellow-legged Gull (Larus argentatus atlantis or L. michahellis atlantis)

The taxonomic positions of the large gulls breeding in the Azores, Madeira and the Canary Islands have been confused for many years. The birds were initially considered a subspecies of the Lesser Black-backed Gull and named Larus fuscus atlantis by Jonathan Dwight in 1925. Individuals breeding in the Canary Islands and on Madeira were reported to be slightly different from those in the Azores, and so some proposed that subspecies atlantis should include only those birds breeding in the Azores. However, by restricting the distribution, it would leave the problem of identifying the birds breeding in Madeira and the Canaries.

Others authors, such as Charles Vaurie, treated atlantis individuals as a subspecies of the Herring Gull, Larus argentatus atlantis, and more recently some have regarded the birds as a subspecies of the Yellow-legged Gull and so should be named Larus michahellis atlantis. To complicate matters further, others suggest that the atlantis birds should be given full species status as Larus atlantis. A paper on the status and identification of the atlantis group appeared in British Birds in 2017, discussing its acceptance as a subspecies that has occurred in Britain. This is based on four well-recorded sightings in England in 2005, 2008, 2009 and 2017 all of which were accepted by the BOU Records Committee in 2016 and 2018.

The photographs accompanying the British Birds paper show two adults and draw attention to the heavy bill. But these birds are almost certainly males, as females have less substantial bills, although this sex difference is not mentioned. Comments that the birds looked powerfully built and heavy-headed ignored sex differences common to all large gull species. I doubt if individual adult females and males can be identified outside of their breeding range. How much variation exists in the extent and duration of the intense head streaking, and does this overlap with other large, yellow-legged gulls?

The reference to the four-colour bill as a criterion for identifying atlantis gulls is not reliable, as this is also seen in some three- and four-year-old Herring Gulls, while the shorter legs and very pale iris are not convincing differences justified by actual measurements. Uncertainty about the 13 Irish records that have been accepted also applies. This subspecies is at the limits of field identification and, if it does indeed occur in Britain and Ireland, a great many individuals (particularly females) will surely go unidentified and fail to be recorded. For certain identification, more extensive ringing is required in the Atlantic islands where the birds breed.

RARE VISITORS FROM EASTERN EUROPE

Caspian Gull (Larus cachinnans)

The Caspian Gull is a large gull that was regarded as a subspecies of the Herring Gull until 2007. Its distribution has often been confused with that of the Yellow-legged Gull, although only some adults have yellow legs. It breeds further east in Europe than the Yellow-legged Gull, mainly around the Black and Caspian seas, and as far east as Kazakhstan and China. It has recently spread further north and west in Europe, with small numbers now breeding in Poland, Switzerland and eastern Germany, where the Yellow-legged Gull also occurs. It frequently forms mixed breeding pairs with Yellow-legged Gulls at some of the European breeding sites.

The Caspian Gull (Figs 217 & 218) is difficult to identify in the field and is a species for the specialist with experience of large gulls. In 2014, the BOU retrospectively accepted the description and photographs of a Caspian Gull seen in 1992 on Radipole Lake in Dorset as the first British record. A nestling said to be of this species, ringed in Switzerland in 1997 and captured at a landfill site in Gloucestershire in November 1999, became the second record. This was followed in November 2007 by a first-year bird ringed at Rainham landfill site in Greater London as a Herring Gull, which had its ring number read in a colony of Caspian Gulls breeding near Minsk in Belarus almost seven years later. Two nestlings that were colour-ringed in Poland in 2008 and 2009 as Caspian Gulls have been seen at three different localities in southern England. However, Yellow-legged Gulls also bred in this Polish colony and so possible confusion over identity may occur when ringing takes place.

FIG 217. A possible second-year Caspian Gull (Larus cachinnans) (left) with two third-year Lesser Black-backed Gulls (Larus fuscus). (Alan Dean)

FIG 218. Immature gull identified as a Caspian Gull (Larus cachinnans), but could be confused with an immature Great Black-backed Gull. (Alan Dean)

Many, but not all, Caspian Gulls have long, slender bills and sloping foreheads that are less smoothly curved than in most Herring Gulls. The neck often appears longer than in the Herring Gull and the eyes of adults are often dark (but not always so). Many individuals appear to have longer legs than Herring or Yellow-legged gulls. The shade of grey on the back and wings is within the range of European Herring Gulls, particularly those breeding in northern Scandinavia, and black markings on the outer primaries also overlap with the variation present in Herring Gulls (and hence this is not the reliable character suggested by some). In late autumn, adult Caspian Gulls often have pure white heads, but a few European Herring Gulls are similar (although most have acquired dark streaks by this time of year). First-year Caspian Gulls often have paler heads than European Herring Gulls of the same age. There is still insufficient information about variation within this species, but the head and bill shape of the smaller female appears to be less pronounced and so it is more readily confused with European Herring Gulls. All of the characters mentioned are helpful aids, but not totally reliable in confirming the identification of all individuals seen in the field. A further problem lies in separating adult Caspian Gulls with pink legs from the large, dark subspecies of European Herring Gulls breeding in northern Scandinavia, which regularly winter in Britain.

Records of Caspian Gulls in Britain and western Europe as a whole have increased dramatically since 2000, as they have in the West Midlands (Fig. 219), mainly as a result of observers being alerted to the possible presence of the species. Most British records have been from south-east England and the Midlands, and only a few have been recorded in Scotland. Most records in the West Midlands and elsewhere are in the period October to February (Fig. 220), which is also when large, dark-winged Herring Gulls from northern Scandinavia are present and occur inland in Britain.

FIG 219. The number of individuals believed to be Caspian Gulls (Larus cachinnans) recorded annually in the West Midlands up to 2010. Data from Dean (n.d.).

FIG 220. The months in which individuals believed to be Caspian Gulls (Larus cachinnans) were first recorded in the West Midlands, based on records from 1999 to 2010. Data from Dean (n.d.).

Caspian Gulls breed on flat ground alongside lakes and reservoirs, not on cliffs as do many other species belonging to the Herring Gull complex. Their diet is similar to that of Herring Gulls, and many of the recorded individuals have been encountered inland in Britain at landfill sites and roosting on reservoirs.

Audouin’s Gull (Ichthyaetus audouinii)

This is a medium-sized gull, the adults of which have a distinctive bill that is dark red with a pale tip (Fig. 221). Fifty years ago, Audouin’s Gull was considered to be one of the rarest gulls in the world, but its numbers have increased dramatically and are now believed to exceed more than 40,000 adults. It is endemic to the Mediterranean, with small numbers breeding in the eastern Mediterranean in Croatia, Turkey and Cyprus, and many now also breed in the western Mediterranean, particularly in the Chafarinas Islands off the coast of Morocco and in the Ebro Delta in north-east Spain. The species is migratory, with the main wintering areas along the coast of north-west Africa, from Morocco to the Gambia. Despite the large numbers now breeding in the Ebro Delta, there are still few records in France and Britain.

Audouin’s Gull is one of the rarest gulls recorded in Britain and has not been reported from Ireland, despite breeding as close as Spain in rapidly increasing numbers. The first British record was of a second-year individual seen at Dungeness, Kent, on 5–7 May 2003. Up to 2017, only eight more individuals were reported, all from the south and south-east coast of England between May and October.

FIG 221. Adult Audouin’s Gull (Ichthyaetus audouinii). (Tony Davison)

The gull’s diet comprises mainly fish, for which it sometimes forages at night, and fishing waste from commercial boats. The Pilchard (Sardina pilchardus) is probably the most frequently taken fish species. In the past, Audouin’s Gull was rarely reported inland and scavenged less than other gulls, but there is evidence that it is becoming more frequent inland in Spain, where it is particularly attracted to feeding in rice fields.

RARE VISITORS FROM THE MEDITERRANEAN AND BLACK SEA

Slender-billed Gull (Chroicocephalus genei)

The Slender-billed Gull is a medium-sized gull that breeds in Turkey and the Black Sea area, across to Kazakhstan, Afghanistan and Pakistan, and in small numbers around the Mediterranean Sea. Numbers have increased in recent years and breeding has spread to Italy, Spain and the Mediterranean coast of France. In 2010, an inland colony was discovered in Algeria.

Adult Slender-billed Gulls resemble Black-headed Gulls, but they do not have a black head at any time of the year. The elongated head shape is very characteristic, and includes a longer bill and often a long neck (Figs 222 & 223); it has a particularly light-coloured eye. The legs are relatively long, and are pale in immature birds and deep red in adults. The birds often dive to capture fish and also search for food on the ground.

This is indeed a rare gull in Britain, with only 10 records to date. The first confirmed sighting was in Sussex in 1960, and the second was in the same county in 1963. No further birds were reported until 1971, when two were seen. There was then a 16-year absence, until two were seen together at Cley in Norfolk in 1987. A further gap of 12 years without a record followed, until a single bird was recorded in Kent in 1999 and two more in the following year, one in Kent and the other in Norfolk. There were then no other accepted records until 2014. The British records are spread from April to August, and are all from the south of England, with none so far recorded in Scotland, Wales or Ireland. The species migrates south to the north-east coast of Africa and into the Indian Ocean, and immature birds often remain within this wintering area. The British records are far less numerous than those for several gull species that breed much further away in North America.

FIG 222. Adult Slender-billed Gull (Chroicocephalus genei). (Pep Arcos)

FIG 223. Adult Slender-Billed Gull in flight (Chroicocephalus genei). (Pep Arcos)

RARE VISITORS FROM ASIA

Great Black-headed Gull or Pallas’s Gull (Ichthyaetus ichthyaetus)

This species has been commonly called the Great Black-headed Gull for at least 150 years, but the less informative but shorter name of Pallas’s Gull has been applied by some since 2000. It breeds in the south of Russia, from the Sea of Azov to the Volga River at Saratov, and in Turkestan and Mongolia. It migrates to the eastern Mediterranean, Saudi Arabia and India, and is rare in western Europe, where the few records are presumably of vagrants. It is surprising that this large gull does not wander more frequently to western Europe, but its main wintering area is to the south and east of its breeding area, and it is even uncommon over most of the Mediterranean.

The large size of the adults, combined with their yellow legs, black head and heavy bill, make them unmistakable in the breeding season. First-year birds have a black tip to the otherwise entirely white tail and are likely to be confused only with immature Great Black-backed Gulls or Yellow-legged Gulls.

There are only a few British records. An adult was shot off Exmouth, Devon, in May or June 1859 and its skin is now in Exeter’s Royal Albert Memorial Museum. An individual was reported in Sussex on 4 January 1910 by H. Walpole-Bond, and an adult male was shot in Kent in June 1915 after it had been seen there in May. Another individual was then seen at Bournemouth, Hampshire, in November and December 1924 and the record was accepted at that time by British Birds, while a single bird was seen on several days in March 1932 at Cromer, Norfolk. These early records were not subjected to rigorous validation at the time, and without detailed descriptions as evidence to back them up, only the 1859 record is now currently accepted. There have been no Irish records, although there was a single record in Norway in September 2014.

The Great Black-headed Gull feeds on fish, crustaceans, insects and small mammals.

RARE VISITORS FROM THE PACIFIC

Slaty-backed Gull (Larus schistisagus)

The Slaty-backed Gull breeds in the northern Pacific on Hokkaido in Japan, in north-east Siberia and south to the Korean Peninsula. Its range has been extended recently to western Alaska, where breeding was first recorded in 1996 within a colony of Glaucous Gulls. There is evidence that its numbers are increasing in some areas and there are currently just over 200,000 adults of this species. Individuals move south in winter to north-east China, the Korean Peninsula and Taiwan, but there are a number of records from North America of vagrants and, most surprisingly, 16 individuals have been recorded in Newfoundland since 2006.

Adults resemble a large Lesser Black-backed Gull, with a slate-grey mantle and pink (not yellow) legs. The most important characteristic of the adult is a string of white tips to the primaries, described as a string of pearls. Immature birds can be confused with those of several other gull species, and claims of sightings in Europe of individuals in their first two years of life are unlikely to be accepted.

The species was added to the British list in 2016, based on one adult seen and photographed at three locations: Rainham in London, and Hanningfield Reservoir and Pitsea, both in Essex, in January and February 2011. A second bird was reported from Ireland in February 2014. These followed the first European record, from Lithuania, in 2008 (and, likely, the same bird was seen in Latvia in 2009). In 2012, individuals were recorded in Iceland, Belarus and Finland. These records are of a gull species that, when in Europe, is at the maximum distance from its main breeding area.