Christy Brzonkala, Doris Garcia, Jessica Gonzales, and Tracy Rexroat are a few of the many American women who have suffered greatly over the past twenty years from sex discrimination in its various forms. They have all turned to the law in search of justice, and they have all been denied justice—for pay discrimination, pregnancy discrimination, and gender-based violence.

Unlike most other countries in the world, the United States does not have a constitutional equality provision guaranteeing equal rights for women. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia has cynically affirmed, “Certainly the Constitution does not require discrimination on the basis of sex. The only issue is whether it prohibits it. It doesn’t.”1 Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg has expressed her wish to see this prohibition added to the Constitution and has publicly stated the hope that in her lifetime she will see women “get fired up about the Equal Rights Amendment.”2 The goal of this book is to help women and men get fired up enough about the absence of this fundamental human right to put it into the Constitution once and for all.

Alice Paul drafted the first Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) in the early twentieth century. She was one of the founders of the National Woman’s Party, which had worked for passage of the Nineteenth Amendment granting women the right to vote. Alice Paul was a Republican, but the National Woman’s Party was nonpartisan. Raised a Quaker, Alice Paul attributed her commitment to her faith. “When the Quakers were founded,” she explained, “one of their principles was and is equality of the sexes. So I never had any other idea . . . the principle was always there.”3 Alice Paul was among those who picketed outside the White House for women’s suffrage, starting in 1917. After months of what was one of the country’s first organized nonviolent civil actions for social change, she and other women demonstrators were arrested and imprisoned for “obstructing traffic.” They went on hunger strikes and endured forced feeding and beatings by prison guards. The brutality of this treatment increased public support for the cause of women’s suffrage, and in 1920 the Nineteenth Amendment was adopted.

Alice Paul, a founder of the National Woman’s Party, who first drafted the Equal Rights Amendment in 1923. (Courtesy of Records of the National Woman’s Party, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.)

Alice Paul then turned her attention to the Equal Rights Amendment, which was introduced in Congress in 1923 to ensure that not only suffrage but all rights would be guaranteed equally to women and men. Representative Daniel Anthony of Kansas, a nephew of suffragist leader Susan B. Anthony, introduced the bill.4 For more than twenty years after its introduction, the ERA was the subject of political debate and legislative deliberations, but it failed to galvanize support and never came to a vote in Congress. Early opposition came from some progressives, who feared it would do away with hard-won protective labor laws for women.

Over time, support grew slowly and the ERA was included in the political platforms of the Republican Party in 1940 and the Democratic Party in 1944. In 1946 the ERA came to the Senate floor for the first time, where it won a majority of votes but not the two-thirds required to pass a constitutional amendment. Beginning in the 1950s, support for both the proposed amendment and the principle of women’s equality grew steadily, reinforced by the passage of the Equal Pay Act in 1963 and the Civil Rights Act in 1964, as well as the growing political power of the women’s movement. Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon, Ford, and Carter all endorsed the ERA.

In 1970, Representative Martha Griffiths organized sufficient bipartisan support to get the ERA out of the House Judiciary Committee, despite the opposition of committee chair Emanuel Celler, using a rare procedural move known as a “discharge petition.” The House passed the bill by a two-thirds majority, but the Senate bill did not make it to the floor by the end of the session. In the next session of Congress, the ERA was passed decisively by both the House (354–24) and the Senate (84–8) on March 22, 1972, with a seven-year deadline for ratification by the states. Article V of the Constitution requires ratification of an amendment by three-fourths of the states (thirty-eight out of fifty).

The text of the ERA, which Alice Paul had rewritten in 1943 to replace her original wording, was a straightforward guarantee of legal equality for women and men:

Section 1: Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.

Section 2: The Congress shall have the power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.

Section 3: This amendment shall take effect two years after the date of ratification.

Initially states rushed to support the ERA. Less than one hour after its passage in Congress, Hawaii ratified the amendment. Within the first year, twenty-two states had ratified the ERA.5 Eight more states ratified it in 1973.6 However, a backlash then started to set in. In 1974, only three states ratified the ERA, and in 1975 only one state did so.7 Over the next four years only one additional state ratified the ERA, in 1977, bringing the total to thirty-five.8 Meanwhile, five states voted to rescind their ratification, starting in 1973, with more following suit in 1974.9 When it became clear by 1978 that the thirty-eight states needed for ratification would be very difficult to reach by the expiration of the seven-year time limit in 1979, legislation was passed by Congress to extend the deadline to June 30, 1982.

In 1980, the Republican Party dropped the ERA from its platform, and Ronald Reagan came out against it, although his daughter Maureen Reagan, also a Republican, continued to campaign intensively across the country for the ERA. During the three additional years before the extended deadline, not a single additional state voted to ratify the ERA despite mass mobilization by the women’s movement. Unions, religious groups, civic organizations, and trade associations all came together for the campaign—teachers, nurses, librarians, nuns, steel-workers, businesswomen, journalists, and more.

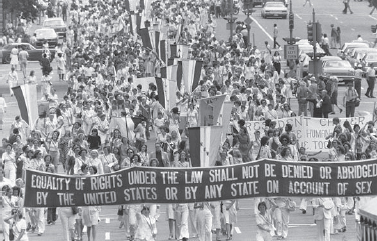

Like the suffragists who came before them, ERA supporters marched, picketed, fasted, and chained themselves to the gates of various halls of power. Presidents Ford and Carter issued a joint call for ratification. First Lady Rosalynn Carter actively supported ratification, and former First Ladies Betty Ford and Lady Bird Johnson participated in rallies organized by the National Organization for Women (NOW).10 Betty Ford served as co-chair of the ERA Countdown Campaign, together with the actor Alan Alda. There were close votes in North Carolina, Florida, and Illinois during this final push, but at the expiration of the extended ratification deadline in 1982, the ERA remained three states short of the thirty-eight needed to put it into the Constitution.11

Supporters of the Equal Rights Amendment march down Pennsylvania Avenue, August 26, 1977. (AP Photo)

Why was the decade-long effort from 1972 to 1982 to get the ERA ratified unsuccessful? In retrospect, what is striking is how very close to success it came. Several nationwide polls in 1981 and 1982 confirmed that a solid majority of Americans supported the ERA. State polls at the time, even in states that had not ratified the ERA, such as North Carolina, Florida, and Illinois, also showed consistent and solid majority support for the amendment.12 As Eleanor Smeal, president of NOW at the time, recalled, “We were just a handful of votes away from victory in three states.”13

For many people, the right-wing political activist Phyllis Schlafly was the face of opposition to the Equal Rights Amendment. She orchestrated anti-ERA activism through her organization, the Eagle Forum, and its STOP ERA offshoot, using fear tactics in an effort to mobilize women and men against the amendment. What were the fears at the time? Fear of women in combat, fear of unisex bathrooms, fear of gay rights, and the unimaginable prospect of same-sex marriage all fed the flames.

Although she herself was a lawyer, Phyllis Schlafly proclaimed that a woman’s place was in the home by her husband’s side, and she warned homemakers that they would lose the emotional and financial security of marriage. She announced proudly at meetings that she had permission from her husband to be present and whipped up venomous opposition to the ERA. In Illinois, where a three-week hunger strike just before the ratification deadline led to the hospitalization of some ERA supporters, anti-ERA women ate chocolate in front of the fasters and held signs with messages such as: “Evil, Rebellious, Agitators, the Communists, lesbians, and homosexuals, and those who work to destroy America and the right to be a true wife and homebuilder are for the ERA.”14

It’s hard to imagine today, more than thirty years later, that these fear tactics could be used with any effect and that they made putting equal rights for women into the Constitution so controversial in some states. Much has changed. Now, the growing number of women in the armed forces want the right to engage in combat and fear that their exclusion from combat, just recently overturned by the Department of Defense, is keeping them from reaching the highest levels of military rank. They want to be recognized for their service and sacrifice. Unisex bathrooms are everywhere and no longer can be used to inspire fear. Marriage equality for gay couples is increasingly recognized as a fundamental right, with support from the Supreme Court and legislation/litigation in a growing number of states. Last but not least, economic security in marriage has turned out to be way less secure than women thought when they campaigned against the ERA to preserve this illusion. Women are increasingly facing many obstacles to economic independence and security, which would more likely be helped rather than hindered by the ERA.

When talking to women and men about the ERA these days, one doesn’t find much argument against it. The resistance, if it exists, is more passive, and it is somewhat mystifying that Phyllis Schlafly drew support from any women for her vision of women as dependent and subservient. The women’s movement forged around the campaign for the ERA went on in the next thirty years to change the face of America and give women more power than they have ever had before. The 1980 slogan “We will remember in November!” sparked a growing recognition of the gender gap at the polls, and there has been a strong and steady increase in the numbers of women elected to political office, corporate boards, and other historically male-only institutions. In 1982 there were 23 women in Congress—by 2014, the number had more than quadrupled to 102.15

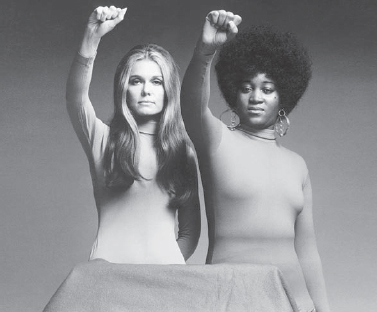

Activists Gloria Steinem and Dorothy Pitman Hughes, co-founders of the Women’s Action Alliance in 1971, who toured the country together to promote women’s rights. (Dan Wynn/Courtesy of Demont Photo Management)

In light of this progress, the question often asked is “Do we really need the ERA? What would it change?” Many Americans—72 percent, according to a 2001 poll—think equal rights for women and men are already guaranteed by the Constitution.16 This misconception is often followed by a renewed sense of outrage at the news that they aren’t. Many people seem to remember vaguely that the ERA “passed” without remembering that, for lack of ratification by just three more states, it failed to enter into force as a constitutional amendment. Very few people today argue against the ERA as a matter of principle. According to a poll in 2012, 91 percent of Americans think the Constitution should include equal rights for men and women.17 The principle of sex equality is one that has largely been established as a given.

Some believe that Phyllis Schlafly was a “front”—that behind her were the interests of insurance companies and other economic interests that opposed the ERA as a financial cost to them to be avoided. Both the United States Chambers of Commerce and the National Association of Manufacturers opposed the ERA. Now, to some degree, the Affordable Care Act has eliminated the discrimination against women that was embedded in insurance industry rates and practices, but only in the context of health insurance. Sex discrimination persists in pricing, wages, hiring, and pensions, just to name a few vitally important financial concerns for women. Most, though not all, explicitly discriminatory laws have been changed in past decades, yet discrimination against women in law also persists in various ways. The adverse impact on women of laws that are seemingly neutral has been well documented but not effectively addressed. We know that women are not yet really equal, whether it is the oft-cited 77 cents earned by women for every dollar earned by men, or the failure of the police to provide women with equal protection of the law as a matter of right in the context of domestic violence.

While many have looked to the Fourteenth Amendment for a remedy for sex discrimination, effective relief has been greatly limited by the way in which the Supreme Court has interpreted it. The Fourteenth Amendment was adopted in 1868 following the Civil War. It was intended to address racial discrimination in the aftermath of slavery by prohibiting states from denying any person “the equal protection of the laws.” Yet it was not until the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified in 1920 that women even had the right to vote, and it was only in 1971—more than a century after the Fourteenth Amendment came into effect—that the Supreme Court for the first time struck down a law under the Equal Protection Clause of this amendment because the law discriminated on the basis of sex. Moreover, the Fourteenth Amendment has been limited virtually from its beginning to state action by government and public officials, while so often sex and race discrimination result from private action by individuals. To the extent that there is federal legal protection from private acts of discrimination by employers and others, it is not constitutionally based on the Fourteenth Amendment.

And to this day, the Supreme Court uses a different and lower standard of review for sex discrimination claims under the Fourteenth Amendment than it does for claims of racial or religious discrimination. While racial and religious discrimination are subject to “strict scrutiny,” sex discrimination is subject to the lower standard of “intermediate scrutiny.” This means that for cases involving racial or religious discrimination, the courts will look to see whether the law under challenge is necessary to achieve a compelling governmental interest, while for cases involving sex discrimination, the courts will look to see whether the law under challenge bears a substantial relationship to an important governmental interest. The governmental interest need not be “compelling,” and the law that furthers this interest need not be “necessary.” It’s ironic, and telling, that the Supreme Court, in enforcing equal protection of the law under the Constitution, does so in a discriminatory manner, holding those who would discriminate on the basis of sex accountable to a lower standard than those who would discriminate on the basis of race or religion.

Even if the Supreme Court were to heighten its standard of review for sex discrimination cases, the Fourteenth Amendment would not be effective in addressing discrimination against women for other reasons. In 1974, the Supreme Court ruled that discrimination against pregnant women did not constitute sex discrimination, although the court recognized that only women could get pregnant. The court found that the exclusion of pregnant women from employment insurance benefits available to others unable to work temporarily did not constitute discrimination against women, disregarding the disparate impact this exclusion has on women.

More generally, systemic bias has not been considered by the Supreme Court to violate the equal protection guarantee of the Fourteenth Amendment unless the bias can be shown to have been intentional. This intent requirement leaves women with no legal recourse under the Fourteenth Amendment for many forms of discrimination, including unequal pay for equal work. Indifference to inequality and subconscious bias have had the same or even more harmful impact on women as intentional discrimination, but the Fourteenth Amendment has not effectively addressed this harm.

The courts have also failed to give women equal protection under the Constitution from discrimination by the police and other agents of law enforcement in responding to violence, leading at times to injuries and even fatalities that might have been avoided if the violence had been taken more seriously, as a violation of constitutional rights. And even though the Fourteenth Amendment guarantees equal protection of the laws, the Supreme Court has upheld a law that treats unmarried men and women citizens differently when it comes to granting citizenship to their children born outside the country.

Without effective constitutional protection from the Fourteenth Amendment for many forms of sex discrimination, and in the absence of an ERA, targeted federal legislation has been used to try to close the gaps, generally relying on the Commerce Clause of the Constitution. The Equal Pay Act of 1963; Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibits employment discrimination by employers with fifteen or more employees; Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, which prohibits sex discrimination in federally funded educational programs; the Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978; and the Violence Against Women Act of 1994 are just a few of these laws. While they have significantly helped women, these federal laws are not comprehensive, many are not fully inclusive, and one has been partially struck down by the Supreme Court for lack of a constitutional foundation. Most critically, none of these laws has the force of a constitutional amendment. That means they do not cover everyone and they can be rolled back at any time by a simple congressional vote. While the process of amending the Constitution is much longer and more complicated than the passage of federal legislation, in the long run the Equal Rights Amendment is a quicker and easier fix than trying to get Congress to pass and the courts to enforce specific legislation addressing each and every form of sex discrimination in the workplace, in schools, at home, and in the community.

In addition to simplicity and efficiency, the Equal Rights Amendment is also an important statement of principle that is much needed in the ongoing effort to move toward meaningful equality between women and men. The law is a formal expression of public policy that plays a critical role in advancing social norms. Laws articulate what we consider to be right and wrong, and can regulate, as well as influence, social conduct. Beyond the value of litigation in providing much-needed access to remedies for women who are discriminated against on the basis of sex, an Equal Rights Amendment will promote public understanding that all men and women are created free and equal in dignity and in rights, and should be treated as such.

Historically women have been treated as second-class citizens, in the United States and around the world—economically, socially, and politically as well as legally. Increasingly, as the women’s movement has grown in strength, governments have recognized and tried to address this discrimination. Yet, to the surprise of many Americans, the United States is one of only seven countries in the world (along with Iran, Somalia, Sudan, South Sudan, and two small Pacific Island nations, Palau and Tonga) that have not ratified the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). Known as the international bill of rights for women, CEDAW has been signed and ratified by 187 countries—virtually every country in the world except ours.

Ratification of CEDAW has not resulted immediately in sex equality in these 187 countries. However, it has given women and men in these countries a declaration of principle and a framework for legal action to translate this principle into practice. The failure of the United States to ratify CEDAW has made it particularly difficult for American women’s rights activists to advocate effectively for action in other countries to strengthen the law and implementation of women’s rights.

CEDAW was signed by President Jimmy Carter in 1980, more than thirty years ago, but it must be ratified by a two-thirds vote of the Senate to enter into force. In their ongoing effort to get the United States Senate to ratify CEDAW, women’s rights advocates have often been told that CEDAW would be a “back door” to the ERA because it prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex, and as a treaty under the Supremacy Clause of the Constitution, it would be considered the law of the land, protecting citizens in all states. While this has always seemed a more compelling argument for rather than against CEDAW, it is high time to go through the front door with the ERA and join the more than 139 countries in the world that have sex equality provisions in their constitutions and/or prohibitions of discrimination on the basis of sex.18

Eleanor Roosevelt chaired the United Nations Human Rights Commission that drafted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which was adopted in 1948 and which she considered one of her greatest accomplishments. She realized, though, that human rights go from local to global:

Where, after all, do universal human rights begin? In small places, close to home—so close and so small that they cannot be seen on any maps of the world. Yet they are the world of the individual person; the neighborhood he lives in; the school or college he attends; the factory, farm, or office where he works. Such are the places where every man, woman, and child seeks equal justice, equal opportunity, equal dignity without discrimination. Unless these rights have meaning there, they have little meaning anywhere. Without concerted citizen action to uphold them close to home, we shall look in vain for progress in the larger world.19

We cannot hope for our country to be a true global leader on women’s rights when we lack legal recognition of women’s equality rights, not only in our international legal commitments but even in our own Constitution.

Last but not least, why now? With so many pressing policy priorities and such a challenging political climate in which to get any legislation passed, is it foolish to think that this is a good time to regenerate the campaign for the Equal Rights Amendment and try to cross the finish line? No, and here is why it makes sense:

First, the ERA is and should be a truly bipartisan issue. Although often now seen as a Democratic Party issue, it was a Republican, Alice Paul, who first drafted the ERA in 1923 and the amendment was first supported in a party platform by the Republican Party. To highlight a common core value of fundamental human rights and be able to move it forward despite the gridlock elsewhere would help restore faith in our legislators and give them a chance to demonstrate their commitment to equality and justice for women across party lines.

Second, the ERA is and should be an issue for men as well as women, both having much to gain from greater equality between them. Old stereotypes are quickly being replaced by new challenges as men increasingly play a greater role at home and women increasingly play a greater role in the workplace. The law needs to catch up with this evolution, at a time when the ugly male chauvinism demonstrated by the opposition to the ERA in the 1970s has been replaced by welcome male enthusiasm for the ERA and deeper understanding that sex equality is good for men as well as women and families.

Third, the passage of state equal rights amendments by almost half of the states in our federal union has demonstrated that there is nothing apocalyptic about the ERA. The more than 139 countries around the world that have made some provision for sex equality in their constitutions have shown the same. To varying degrees, state amendments have succeeded in advancing sex equality beyond what the Fourteenth Amendment has been able to achieve. Meanwhile, as interpreted by the Supreme Court, the Fourteenth Amendment has blocked efforts to advance sex equality as much as it has promoted them, underscoring the need for an Equal Rights Amendment to the Constitution that will benefit women and men in all states.

Fourth, a new generation of young women and men who have little or no patience for inequality are ready to lead the charge for the ERA. They can benefit from, and build on the experience and wisdom of, the veteran activists who gave a decade of their lives to this cause from 1972 to 1982, and who hope to see it succeed in their lifetime. The new generation of ERA supporters brings youthful energy, fresh perspective, social media skills, and a renewed sense of urgency drawn from their impatience with the slow pace of progress—all of which make the movement for the ERA unstoppable.

This book, primarily through cases that have shaped the law as it is today, highlights women who have marshaled the courage to challenge sex discrimination they have faced in their lives. Their cases show how the law has failed to deliver them justice, and how it has undermined rather than strengthened efforts to remedy sex discrimination. Hopefully, you will come to understand why we need the ERA and you will join the growing effort to put equal rights into the Constitution, once and for all. It is long overdue.

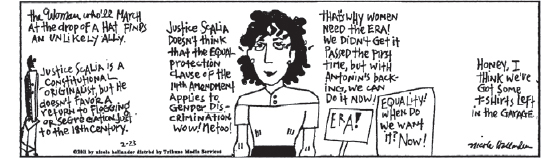

(Nicole Hollander)