3

Parties, Stages, and Studios

Having established the places where daily hair preparation transpired—the quotidian spaces of bedrooms, barbershops, and parlors—we now turn to the places where the results were put on display. The social, celebratory purposes of these dramatic places reflect the same commitment as everyday places did to the aggregate, communal meaning ascribed to hair practices. Cultural geographer Yi-Fu Tuan’s concept that emotion infuses places is a useful framework as we consider the complex decisions women made about their appearance before presenting themselves in social settings, not least of which were the color and style of their hair.1 Social places served as venues for individual and communal performances, and, in turn, as cultural geographer Nigel Thrift says, the “urgencies and needs of performances produce and shape those places.”2 This chapter focuses on the ways that women’s decisions and considerations about their hair acted within and reacted to certain performance-based places. These include a Black performer refusing to wear a wig, a brunette actress dyeing her hair blond for a play, and a family of four posing for a tintype in a photography studio, documenting their appearance for posterity.

Parties and Stages

It is noon on New Year’s Day in New York, and the “artistes in hair” have been working since midnight to accommodate their clients before they begin their rounds of calling at friends’ homes. As James Dabney McCabe, author of Lights and Shadows of New York Life (1872), observed: “Of course those whose heads are dressed at such unseasonable hours cannot think of lying down to sleep, as their ‘head-gear’ would be ruined by such a procedure. They are compelled to rest sitting bolt upright, or with their heads resting on a table or the back of a chair.”3 McCabe sometimes exaggerates, but for upper-class white women who attended society events, displaying a proper hairdo was as requisite as wearing a fine outfit. Hairdressers put in many hours of work to meet the demand. Christmas Day, Thanksgiving Day, and the Fourth of July were also grand events, but in some circles, a Monday night dinner party at a friend’s home after the opera might require near-equal elegance. In high society, dressed hair signaled respectability, and unbound hair was a sign of disrepute because it was believed to be irresistibly alluring to men.4 The norm was for girls to wear their hair long or pulled back into a middle braid fastened with a bow or perhaps under a hat (see figs. 3.12, 5.2). When they reached their teens and were officially available for marriage, they began to bind and dress their hair. Wealthy families marked the occasion with a coming-out party that introduced the young woman to society. In her autobiography, Frances E. Willard, educator and founder of the World Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, quotes a vibrant entry from her girlhood journal describing the difficulties of the transition for her: “This is my birthday and the date of my martyrdom. Mother insists that at last I must have my hair ‘done up woman-fashion’. . . . My ‘back’ hair is twisted up like a corkscrew; I carry eighteen hair-pins; my head aches miserably.”5

The places in which social activities took place varied by class and race, and each had its own code of acceptable hairstyles. As guided by etiquette books, upper-class and middle-class white women adhered to the norm of having their hair fully prepared before stepping into social places, whether their own dining room with family members for breakfast, the parlor in which they entertained friends, a friend’s home, a department store, a museum, or an opera house.6 Having “smoothly-arranged hair” was one of the hallmarks of a lady, along with walking and speaking well, standing with proper posture, and acting politely.7 Etiquette books warned women against fussing with their hair after arriving at the destination. At a friend’s home, they should “avoid all such tricks as smoothing your hair with your hand, arranging your curls.”8 At a ball, they should “Be very careful, when dressing for a ball, that the hair is firmly fastened, and the coiffure properly adjusted. Nothing is more annoying than to have the hair loosen or the head-dress fall off in a crowded ball room.”9 Such guides make clear that social settings were performance places and that any adjustments needed to be made “off stage” in a dressing room that was stocked by the host with extra hairpins for guests.10 A misstep could condemn a woman as slovenly and unkempt.

Women in the public eye might become known especially for their hair, setting styles to which middle-class women could aspire. First Ladies, socialites, and actresses became hair icons, with their choices chronicled in magazines and newspapers and reproduced in cabinet cards. Throughout her years in the White House (1877–1881), First Lady Lucy Hayes was admired for her modest self-presentation, exemplified by her “shining mass of satin hair,” consistently worn in a tight, center-parted bun.11 In 1886, the fashionable twenty-one-year-old Frances Folsom of Buffalo, New York, married sitting president Grover Cleveland. Her short bangs, curled at center away from her forehead, and the rest of her hair pulled into a back knot swiftly earned the moniker “à la Cleveland,” and women across the country strove to copy the look, consulting the abundance of available images, many of them unauthorized (fig. 3.1).12 Her hairdresser that year was Joannes (John) Rochon, who owned a hairdressing and wig establishment on Fourteenth and Fifteenth Streets in Washington, DC. President Cleveland reportedly curtailed Rochon’s employment after learning that he apparently had abandoned his wife in Lyon, France, when he moved to the United States.13 Rochon remained in business well into the 1890s, however, advertising frequently and often claiming the title “Professor.” Frances Cleveland’s later hairdressers were also successful, as her styles (always with brown hair) were still making the papers in 1894 when she sported a “Diana knot” situated at the top of the head and with the front hair in a middle part (fig. 3.2).14

When Frances Cleveland introduced her new styles at state events in the White House and soirées throughout Washington, DC, elite guests saw and copied her hair, but so did middle-class U.S. women who read the press coverage in their local papers. Cleveland’s personal style inflected places well beyond the homes of government leaders, spreading throughout the country. Following Cleveland, socialites in major U.S. cities also experimented with novel styles, often gaining national attention. As the Arizona Republican reported in 1891: “There are few noted beauties among New York society women whose coiffures, no matter how seemingly natural, have not been the subject of careful study to themselves, their maids and the clientele of admiring hangers on who hover around the shrines of wealthy belles.”15 A few of the most notable were Amy Bend (“hair, of the lightest gold, as pale as wheat ears in moonlight and as fluffy as spun silk”);16 Sarah Lawrence “Susan” Endicott Roberts; and Florence Hamilton Davis, later Flora Curzon, Lady Howe.

Figure 3.1

Charles Milton Bell (U.S., 1848–1893). Frances Folsom Cleveland, 1886. Albumen silver print, 12 × 9 cm. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. Gift of Francis A. DiMauro (NPG.2007.292).

Figure 3.2

Anders Leonard Zorn (Swedish, 1860–1920). Frances Folsom Cleveland, 1899. Oil on canvas, 138.3 × 93.2 cm. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. Gift of Frances Payne (S/NPG.77.124).

In addition to its color and texture, the hair of women of high society was admired for its tasteful arrangements, most often described in the ways in which it was contained, including soft knots, tight braids, or compact coils. In nineteenth-century literature, undone hair carried associations of promiscuity or of fallen women, such as Mary Magdalene.17 Wisps or curls of hair escaping from a chignon could be considered unruly.18 Only on rare occasions was it acceptable for society women to wear their hair unbound and flowing in public. One of those times was when masquerading at a ball, wearing the costume of Ophelia from Hamlet or Juliet from Romeo and Juliet, for instance.19 Then the hair could extend well past the shoulders, taking a cue from performers like the British actress Ellen Terry, who wore her hair relatively undone when she played the role of Ophelia at the Lyceum Theatre, London, in 1878. On the same stage in 1888, she played Lady Macbeth, donning enormously long red braids beneath a crown. John Singer Sargent captured the dramatic look in a celebrated portrait of 1889, now at Tate Britain.20

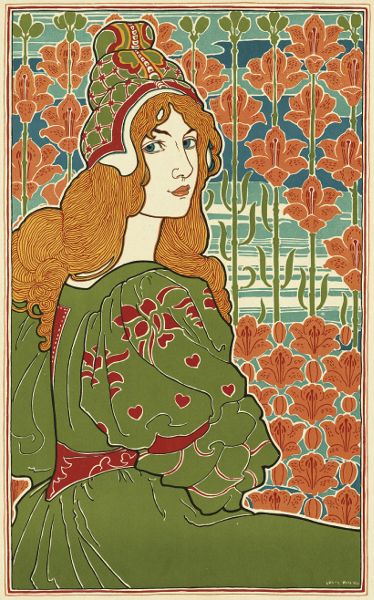

French actress Sarah Bernhardt frequently appeared on U.S. stages, and her image, like that of Ellen Terry, circulated widely in cabinet cards and in the press. Her “Titian hair”—red and curly or frizzy—delighted audiences and artists. It might be described as hanging in a “neglected manner” or “scattered,” but it also represented the freedom granted by the stage setting for how women could present themselves.21 Polish actress Helena Modjeska often arranged her hair to “float naturally over her shoulders,” as when she played Ophelia in Kraków in 1867.22 Certain parameters were maintained, though. For the role of Gismonda in the eponymous play by Victorien Sardou at the Théâtre de la Renaissance, Paris, in 1895, Bernhardt wore her hair at shoulder length, rather frizzy, with bangs (fig. 3.3). On the top of her head, depending on the scene, she alternated between wearing a faux orchid headdress, a Byzantine cap, and a large, round dark hat with white feathers. Czech artist Alphonse Mucha, who worked in Paris, captured the dreamy, classical look of the floral headdress for posterity in his Art Nouveau poster created for the opening (fig. 3.4). In the image, Mucha straightened Bernhardt’s hair considerably, drawing attention to it by depicting her left forefinger touching the ends. Théobald Chartran softened and lengthened her curls in his portrait of her in 1896.23 Mucha and Chartran were not the only ones to use artistic license with the Gismonda hairstyle. By 1900, the style was still holding the popular imagination. In February that year, Violet Lee Willing of Philadelphia, whose sister Ava Willing married John Jacob Astor IV, favored a style called “the Gismonda,” supposedly inspired by Bernhardt.24 However, images of the arrangement along with instructions of how to obtain it show a puffed, tripartite updo. Ornamentation might include ribbons, velvet, flowers, or gauze butterflies. Other than a sense of roundness and volume, the outcome hardly resembles Bernhardt’s original look, suggesting that society women deliberately tamed the style while retaining its name and association with one of the international stars of the stage.

Figure 3.3

Studio of Nadar (French, mid- to late 19th century). Sarah Bernhardt in “Gismonda,” 1895. Photograph (silver gelatin print), 14.5 × 10.5 cm. Image: Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

U.S. actress Maude Adams wore her hair at different lengths while performing. The prominent Sarony photography studio captured her looks from The Little Minister (Empire Theatre, New York, 1897) (figs. 3.5, 3.6) and Romeo and Juliet (Empire Theatre, New York, 1899),25 as did Pach Brothers and the Byron Company. Mucha later painted her as Joan of Arc, altering her long hair from brown to strawberry blond.26 Adams’s hair appears natural, even in the collage photograph showing three different styles, but some performers might use quantities of false hair to achieve stage-worthy looks.27 Actresses’ countenances were so well recognized from cabinet cards and posters that one newspaper article of 1893 about dress and beauty ran line drawings without a single caption providing a woman’s name.28 Actresses with top billing could sway the season’s hairstyles, despite the wishes of the premier hairdressers (coiffeurs in French). French actress Jane Hading was known for her naturally wavy and abundant red hair, so in 1886, when she opted for a simple Greek bandeau style that did not require much expertise, the coiffeurs were displeased.29 Italian opera singer Adelina Patti, who wore elaborate hairstyles on stage, lent her name to hair product testimonial advertisements for the Imperial Hair Regenerator Company.30

Figure 3.4

Alphonse Mucha (Czech, 1860–1939). Sarah Bernhardt as Gismonda at the Théatre de La Renaissance, Paris, 1895. Color lithograph print on paper, 216 × 75.3 cm. Image: Victoria and Albert Museum, London (E.261-1921).

Figure 3.5

Sarony photography studio (New York). Maude Adams as Lady Babbie in “The Little Minister,” 1897. Cabinet card (mounted silver gelatin print), 16.5 × 10.8 cm. Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Figure 3.6

Otto Sarony (U.S., 1850–1903). Maude Adams. Cabinet card (likely mounted platinum print), 1901. Courtesy of the Ringling Theatre Collection, Belknap Collection for the Performing Arts, Special and Area Studies Collections, George A. Smathers Libraries, University of Florida.

In the case of Sissieretta Jones (Matilda Sissieretta Joyner Jones), a U.S. Black woman who sang soprano on stages in the 1890s, we have a statement attributed to her with regard to her intention with her hairstyle. Jones, from Portsmouth, Virginia, wore her hair pinned back with curls in a front pompadour (fig. 3.7). This was the style she wore in front of national and international audiences, from Madison Square Garden to the White House and to the World’s Columbian Exposition. As reported in the New York Times, she refused to wear a wig, saying she “would not hide what I am even for an evening.”31 After the turn of the century, she wore a larger, rounded bouffant.32

The extent to which women followed the lead of stage performers varied. As mentioned above, upper-class white women might take the opportunity of a fancy ball to try an undressed look. At this type of ball, you could set your hair free for an evening. At Alva Vanderbilt and William Kissam Vanderbilt’s famously extravagant ball of 1883 at their new mansion on Fifth Avenue in New York, Alva dressed as a Renaissance duchess. Underneath a period headdress, her curly brown hair extended well past her shoulders. As Joan of Arc, Lucy W. Hewitt did the same at the party, her curls spilling out from an armorial helmet. Helen Bulkeley Redmond as the water nymph Undine and Charlotte Augusta Astor Haig as Night wore their straight hair flowing to their waists.33

Hair Color as Performance

Experimenting with unbound hair at fancy balls was one way that society women claimed license with their hair, perhaps emulating the freedom of actresses on stage. Another method was by altering their natural color. This manipulation, well-documented in the press, opens a lens onto how color and dye were perceived and to what degree nonactresses made their choices visible in society. Actresses’ natural shade versus a dyed variant fueled the gossip pages, as did Georgie Drew Barrymore’s blond locks (“so, they whisper”) in 1892.34 Life mused on actresses: “She is blonde, but she hasn’t been blonde so very long. On the stage, blonde hair means innocence and virtue; off the stage it doesn’t—at least, not always.”35 In Lights and Shadows of New York Life, James Dabney McCabe writes about a naturally blond dancer who dyed her extra hairpieces backstage: “her diamonded fingers were hard at work saturating some superb yellow tresses in a saucerful of colorless fluid, a bleaching agent for continuing the lustre of blond hair.”36

Figure 3.7

Napoleon Sarony (U.S., 1821–1896). Sissieretta Jones, ca. 1895. Albumen silver print, 14 × 9.7 cm. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC (NPG.2009.37).

In reality, the blond shade was never considered fully respectable or unrespectable. At any given time, some visual and written sources praise the shade on women, and others condemn it. In her book On Blondes, Joanna Pitman notes that Charles Dickens typecast blonds as innocents in his novels, while the Pre-Raphaelite painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti set them as femmes fatales.37 Literature scholar Edith Snook notes that the ideal woman in early modern England had an abundance of blond wavy hair, which became a marker of privilege.38 Carol Rifelj observes a spectrum of attitudes toward blonds, with some authors assigning the hue to temptresses and others to natural beauties.39 The Northern Italian Renaissance painter Titian often portrayed blond women both as allegorical figures and as courtesans. In the mid-nineteenth century, fair-headed Empress Eugénie of France set off a craze for flaxen hair by those emulating this noblewoman who married Napoleon III.40 Throughout the nineteenth century, Currier and Ives and other lithographers published color prints depicting their conception of types of ideally beautiful white women. Whereas “New York Beauty,” “Belle of Brooklyn,” and “Star of the South” were brunettes, there was also the “Beautiful Blonde” (fig. 3.8).41 Etiquette books might not moralize about the shade but rather focus on clothing colors that complement blond: “Pure golden or yellow hair needs blue,” writes one.42 As for Currier and Ives’s “Queen of the West,” she was a redhead (fig. 3.9).

Red hair had a longer history of correlation with danger and betrayal, including the biblical figure Lilith, the barbarians in Greek and Roman theater traditions, and Edouard Manet’s paintings with Victorine Meurent as model, often posing as a courtesan, as in Olympia (1863, Musée d’Orsay, Paris).43 The aforementioned Frances E. Willard’s autobiography offers a sense of the shame that could accompany red hair. As a child, she hated her “positively red” hair.44 Children would shout “red head” as an epithet at her, and her mother would not use the word “red,” preferring “bright colored.”45 Historian Ruth Mellinkoff explains that the negative associations with red hair stems from its classification as a “minority feature,” occurring in about 2 percent of people.46

But the Pre-Raphaelite painters in England famously celebrated redheaded beauties, accentuating their appeal to male viewers by portraying them with abundant, soft, and frequently unbound hair. Rossetti’s model Elizabeth Siddall popularized red hair, and two of his other models also had red hair—Fanny Cornforth, who became his mistress, and Alexa Wilding.47 In his paintings, they might comb, plait, or braid their thick red hair. For John Everett Millais’s painting Portia (1886), model Kate Dolan posed in a red sixteenth-century-inspired costume that redheaded actress Ellen Terry wore when she played the role. The influence of the Pre-Raphaelite painters’ penchant for Shakespearian, decorative, and allegorical scenes featuring redheaded women is seen in paintings by U.S. artists like Albert Herter. His Woman with Red Hair (1894) presents a profile view of a porcelain-skinned woman whose soft red hair is pulled into a low knotted bun. Curlier hair frames her face, which is topped by a black tiara, perhaps made of jet. The composition emulates Renaissance portraiture, while the abstract floral background exerts the decorative impulse of the late nineteenth century.48 Perhaps the most salient throughline from the Pre-Raphaelite influence appears in the proliferation of redheads starring in posters, advertisements, and other printed ephemera toward the turn of the twentieth century. Louis John Rhead, who created images for Prang and Company, Harper’s Bazar, and Century Magazine, among others, foregrounded redheads in his work (fig. 3.10).

Figure 3.8

Currier and Ives (U.S., 1857–1907). Beautiful Blonde, 1872–1874. Hand-colored lithograph, sheet 41 × 31 cm. American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts.

Figure 3.9

Currier and Ives, Queen of the West, 1877–1894. Hand-colored lithograph, sheet 45 × 35 cm. American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts.

In the context of the nineteenth-century United States, the Currier and Ives “Queen of the West” print (see fig. 3.9) shows that any strict connection between red hair and either villainy or unrestrained eroticism is overstated.49 This ideal type of redhead wears her wavy hair in a classical arrangement, center-parted with a gold and gemmed floral diadem and additional hair jewels. Her skin is pale white, and her cheeks are blushed, representing the epitome of white beauty in the period.50 Available at reasonable prices, Currier and Ives prints like this one brought ideal beauties, redheads included, into scores of middle-class homes. As one etiquette book reassured its readers: “No shade of hair is unlovely, if luxuriant and healthy in growth.”51 Writings in women’s diaries echo the sentiment that abundant hair signaled health and beauty and express concern and dismay when illness affects hair growth and texture.

Eliza Frances Andrews, an educator and botanist from Georgia, wrote that before leaving for a social engagement, she arranged her sister’s hair: “I fixed Metta up beautifully, though, and she was very much admired. Her hair that she lost last fall, from typhoid fever, has grown out curly, and her head is frizzled beautifully all over, without the bother of irons and curl-papers.”52 Hair figures prominently throughout Andrews’s journal. She frequently becomes wary of curling her hair only to have damp air flatten the spirals: “I am tired of frizzing, anyway, though it does become me greatly.”53 She had “false frizzettes” made up of her and Metta’s hair, but those would not stay curled either.54 At times she wished her hair was longer, and she freely commented on the hair of other women: one had “dull, coarse hair of an undecided color,” and another had “hair of a rich old mahogany color that I suppose an artist would call Titian red.”55 Advertisements for hair treatments split the difference between blonds, brunettes, and redheads but always emphasize healthy, lustrous locks.56

Figure 3.10

Louis John Rhead (U.S., 1857–1926). Jane, 1897. Color lithograph, 40 × 31 cm. Boston Public Library (2012.AAP.310).

Many hair products promised to restore gray hair to its original color, like Ayer’s hair vigor, or even prevent gray hair, like Hall’s vegetable Sicilian hair renewer. Despite the proliferation of these products, however, gray hair was not shunned on women who chose to wear their hair naturally, and hairstyles specifically for older women appeared on the pages and covers of Harper’s Bazar.57 A watercolor on ivory miniature by Laura C. Prather of an unidentified woman appears to celebrate the white hair of the sitter, the light source from the upper left shining on the right and center upsweeps of smooth hair and on her forehead (fig. 3.11).

Society women’s natural hair color was publicly known, so when it changed, gossip columnists took note. Alice Claypoole Vanderbilt had soft brown hair, Alva Vanderbilt’s was “ruddy bronze brown,” and Louise Vanderbilt’s was golden and gleaming.58 When in 1897, at the age of forty-four, Alva Vanderbilt (at this point named Alva Vanderbilt Belmont, having recently married Oliver Hazard Perry Belmont) dyed her hair to hide its silvers, the change warranted a three-paragraph item in the papers.59 In overstated terms, she was said to have changed her “almost raven black” hair to the costly “No. 4 chestnut,” now looking ten years younger and resembling more closely her daughter, the well-known beauty Consuelo, duchess of Marlborough. The cheekiness with which changes in hair color were parlayed reflects the continuing stigma against hair dyeing, which, as historian Steven Zdatny points out, lasted well into the twentieth century.60 Accordingly, the places where this process could happen were private rooms, their candor advertised by hairdressers like the aforementioned Christiana Carteaux, who advertised that one of her establishments in Providence, Rhode Island, had a separate room for hair dyeing.61 Likewise, Mrs. M. L. Baker of Philadelphia offered private rooms for hair dyeing and emphasized the safety of the black and brown dyes she used.62 In the 1860s, synthetic dyes began to be used as hair colorants, although the process of “blondining” to achieve blond hair seems to have retained the formula of applying ammonia, followed by hydrogen peroxide.63 Before then, plant- and animal-based dyes were used but might be supplemented by dangerous additions of lead or sulphuric acid. Books like Dr. Charles Henri Leonard’s The Hair: Its Growth, Care, Diseases and Treatment (1881), however, indicate that well after synthetic dyes were available, packaged and homemade concoctions often contained dangerous combinations of ingredients that could be poisonous if ingested or absorbed by the skin. They might include silver nitrate, lead oxide, lead acetate, copper sulphate, or iron rust.64 Leonard warns about keeping children away from the dyes.65 Another hair care book warned that packaged dyes did not always disclose their ingredients and should be checked carefully by the customer.66 In 1899, physical fitness proponent Bernarr Macfadden advised against any hair dyes, stating that most of them included lead, a point supported by medical publications.67 A safer, more durable dye would be invented by French chemist Eugène Schueller, founder of L’Oréal, in 1909.68

Figure 3.11

Laura C. Prather (U.S., 1862–1932). Seated Woman with White Hair, 1900. Watercolor on ivory, 10.1 × 7.6 cm. Worcester Art Museum. Gift of Lewis Hoyer Rabbage (1995.68.9). Image: © Worcester Art Museum, Massachusetts, USA/Bridgeman Images.

Portrait Studios

The portrait studio was a place where society leaders and actresses deliberated over just the right look and made their hair color and style choices eminently visible. Helen Ward, a hairdresser in Washington, DC, wrote about preparing the naturally blond hair of writer Amélie Rives Troubetzkoy for a portrait for her husband’s family. Rives’s second husband was Russian prince and painter Pierre Troubetzkoy. According to Ward,

That woman has driven me crazy three distinct times. She came to me three days in succession to get her hair dressed in the style of a Russian litterateur. She wanted it in a Psyche, and she was determined to have it wild. I lay awake till morning and dreamed it out in one minute after she arrived at daylight to get it done.69

An oil-on-canvas portrait by a leading painter could cost thousands of dollars and was meant to capture a person’s appearance for posterity. Even the wealthiest patrons commissioned only a few portraits over their lifetimes, so for women, the choice of hair and dress carried magnitudes of importance. John Singer Sargent could spend weeks planning and painting a portrait, as he notoriously did for Madame X, a portrait of Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau, in 1883 to 1884 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York).

For Mrs. Fiske Warren (Gretchen Osgood) and Her Daughter Rachel, the sitters visited Sargent’s temporary studio at Fenway Court, the palazzo that housed Isabella Stewart Gardner’s magnificent art collection (figs. 3.12, 3.13).70 Mother and daughter sit on ornate chairs and wear satin dresses in varying shades of pink. Sargent highlights their auburn hair from the upper right, their locks merging into one another’s. Fiske was thirty-two years old at the time, and her loose hairstyle is appropriate for her, an intellectual poet. She avoids an overly exaggerated pompadour bouffant so often seen at the turn of the century (see fig. 5.22). Eleven-year-old Rachel’s hair is pinned up only in the front, and the rest tumbles past her shoulders.

Figure 3.12

John Singer Sargent (U.S., 1856–1925). Mrs. Fiske Warren (Gretchen Osgood) and Her Daughter Rachel, 1903. Oil on canvas, 152.4 × 102.5 cm. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Gift of Mrs. Rachel Warren Barton and Emily L. Ainsley Fund (64.693). Photograph © 2024 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Figure 3.13

John Templeman Coolidge (U.S., 1856–1945). John Singer Sargent Painting Mrs. Fiske Warren and Rachel Warren, 1903. Photograph. Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston.

It was prudent to select a subdued or even outright traditional hairstyle rather than a seasonal fad so that the sitter would not regret the decision and attempt to call back the artist to adjust it. One New York writer warns of the expense incurred by a woman who wore a Langtry knot (after English actress Lillie Langtry): “fashions change, and when she took to bangs her portrait did the same.”71 Miniature watercolor-on-ivory portraits by reputable painters, although significantly smaller in size also required strategic hair choices (fig. 3.14; see also fig. 3.11).

Posing for a portrait in a photographer’s studio allowed for more variations in hairstyle. It could be a formal affair, and, as noted in chapter 2, hairdressers and photography studios made happy, profitable neighbors. In the early decades of daguerreotypes (images made on a silvered copper plate; introduced in the United States in 1839) and ambrotypes (images made on coated glass; invented circa 1854), which were unique creations that could not be reproduced, we see careful self-presentations with contained hairstyles (fig. 3.15). Although by the 1850s exposure times had been reduced from several minutes to under one minute and the risk of blurring the final image was no longer as dire, sitters often appear to be holding a preconceived pose. They were also seated in straight-backed chairs, possibly leaning into a metal head brace. They rarely smiled and wore dark clothing to increase the success of the final result, and it is difficult to detect emotion, though there must have been a great sense of anticipation. In the heyday of daguerreotypes, prices varied depending on the provider. Itinerant practitioners might charge less than a dollar for an image, whereas the renowned firm Southworth and Hawes in Boston (ca. 1843–1860) charged about $15.72 Robert Douglass Jr., a Black daguerreotypist in Philadelphia, charged about $5.73 The advent of the durable, less costly tintype in 1856 (about $1 per image) led to a relaxing of formality. Sitters could keep the dog in the shot, if they wished.74

Later in the century, commercial photography studios proliferated throughout the country, producing affordable paper photographs and cabinet cards that could be made in multiples. Stamped names and addresses on the front or back of the cards became an effective way to market a business’s services and show historians how pervasive the establishments were throughout the country, from small town to bustling metropolis. The tintype’s lower cost allowed people to make repeat visits to the photographer and document the growth of a family (and generational resemblances) over the years. Standard studio backdrops were painted on fabric and could be purchased from photography supply companies.75 They might show a distant landscape through a window, classical sculptures or ruins, or an architectural scene. Photographers took great care to match the sitters with an appropriate, albeit generic, background. For instance, a family wearing winter clothing would not be set against a summer meadow backdrop.76

Figure 3.14

Carl A. Weidner (U.S., 1865–1906) and Fredrika Weidner (U.S., 1865–1939). The Daughters of Heber Reginald Bishop (Elizabeth, Harriet, Mary, and Edith), ca. 1895. Watercolor on ivory, 9.5 × 7.6 cm. New-York Historical Society. Gift of the Estate of Peter Marié (1905.22). Image: © New-York Historical Society.

Figure 3.15

Glenalvin J. Goodridge (U.S., 1829–1867). Mrs. Glenalvin Goodridge (Rhoda), 1859. Ambrotype, 8.3 × 7 cm. Smithsonian American Art Museum, the L. J. West Collection of Early African American Photography.

Likewise, professional retouchers of photographs were instructed to be attentive to areas around the hair and to avoid creating an unnatural division between the scalp and where the hair falls on the neck or clothing, which could indicate a wig.77 Painting hair colors onto a black-and-white photograph entailed another set of detailed instructions, rivaling the recipes for homemade hair dyes, though with paint colors (burnt sienna, raw umber, a dash of sepia).78 The well-to-do Black family photographed by the Aultman Studio in Colorado in 1897 is set against a backdrop showing a contemporary building, perhaps meant to evoke a civic building or university (fig. 3.16). The three women of the family wear their hair pinned up, and their fine dresses suit the occasion.

Figure 3.16

Aultman Studio (Colorado). [Portrait of a family], 1897. Glass negative, 13 × 18 cm. History Colorado (93.322.318).

This chapter has examined how women strategized the presentation of their hair at parties, on stages, and in portraits taken in painters’ and photographers’ studios. Women contemplated how to present the style and color of their hair, knowing that their choices would be made visible to their peers either for an evening, in the case of a celebration, or for posterity, in the case of a portrait. The process of decision making before entering certain places speaks to how women’s thoughtfulness, deliberation, and, for Sissieretta Jones, refusal to wear her hair a certain way, held the potential to change how entire places looked and felt. Jones’s choice to wear her natural hair in a pompadour instead of under a wig meant that she brought more of her whole self to the stage in front of what was likely a mostly white audience. The viewers watched, while her natural voice and hair communicated back. Women used the medium of hair to express personality and infuse emotion into places, albeit within the communally constructed boundaries of decorum. There was a degree of self-determination in how women presented themselves that may be discerned by paying attention to their choices of hairstyle and hair color. The next chapter contends with places of labor, further emphasizing how a consideration of hair functioned not only in the workplace but also in the marketplace once the manufacturing and merchandising of hair products began to proliferate. Depending on class and race, the level of control over one’s hair and head coverings differed greatly in the two arenas.