CHAPTER 4

EVALUATING WHAT WORKS AND MANAGING FRUSTRATION WITH WHAT DOESN’T

If we grow up fearing mistakes, we may become afraid to try new things. Making mistakes is a natural part of being human and a natural part of the way to learn. It’s an important lesson, at any time of life, but certainly the earlier the better. We all make mistakes as we grow, and not only is there nothing wrong with that, there’s everything right about it.

—Fred Rogers, host of the children’s television show Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood

You may have noticed that the weekly objective worksheets thus far are written in a very “all-or-nothing” manner. An individual either achieves total success on an objective, or they do not. As pointed out previously, all-or-nothing or black-and-white thinking can lead a person to focus solely on their failures unless they meet an objective 100%. But, in reality, progress matters, even if we don’t completely achieve the goal.

As you work toward your goals from week to week, you must think through the process and evaluate what works and what doesn’t. This includes examining both the behavioral coping strategies that you try (such as the ones in Part II of this book) and the cognitive process you are using (as discussed in Chapter 1). This practice ultimately assists you in knowing when and how to apply what skill for not only current but also future goals. Moreover, it will help you to remain confident and hopeful throughout your journey. Because of this, I include our fifth and final step: evaluating what works and managing frustration with what doesn’t.

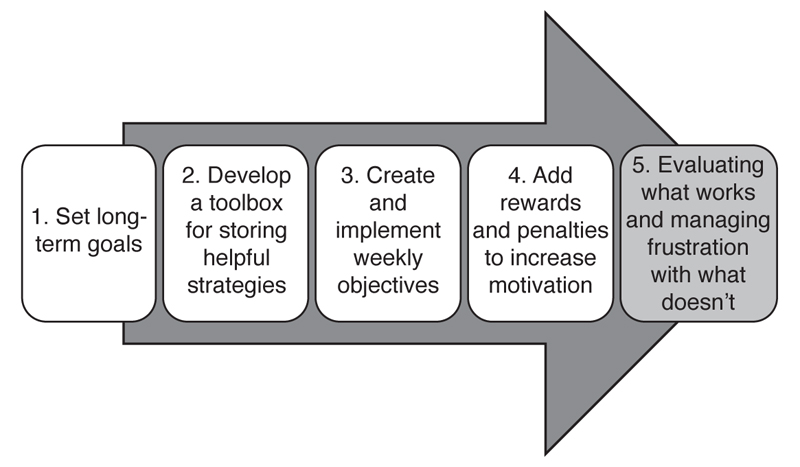

Steps for Achieving Your Goals

Long Description.

The flowchart contains 5 labeled boxes and develops from left to right as follows.

1. Set long-term goals

2. Develop a toolbox for storing helpful strategies.

3. Create and implement weekly objectives.

4. Add rewards and penalties to increase motivation.

5. Evaluate what works and manage frustration with what doesn't. This step is highlighted for discussion in the text.

Description ends.

QUIZ YOURSELF—DOES THIS SOUND LIKE YOU?

- Does it feel like you are just going through the motions, repeating the same (unhelpful) behavior patterns over and over?

- Do you feel like you are capable of so much more but don’t know what is holding you back?

- When asked “why” you did or did not do something, do you tend to think “I don’t know” or “I wasn’t thinking”?

- Do you see unmet objectives or goals as failures?

WHAT THE EXPERTS SAY

Psychologists have a fancy word to describe the evaluation of one’s cognitive strategies. Metacognition refers to higher order thinking that involves active regulation over the cognitive processes engaged in learning. Literally, it means “thinking about thinking.” To successfully move from a position of simply going through the motions, using external incentives to guide behavior, to a point at which you can internally monitor and control goal-directed behavior, you must actively think about the way you approach a given task, what works and what doesn’t in terms of helping you to complete it, and what you can change moving forward. Metacognition encompasses various cognitive processes, such as self-awareness, self-monitoring, and self-regulation (Knouse et al., 2005), which impact adaptive behavior in various environments. In various clinical populations, deficits in self-awareness of cognitive ability were shown to have a negative impact on everyday life (Rothlind et al., 2017), suggesting that metacognition may be particularly relevant in the clinical context.

One aspect of metacognition that is known to affect learning and coping is one’s mindset. Carol Dweck, PhD, of Stanford University, coined the term “growth mindset”—the belief that our brains have the ability to grow and develop, and that putting in extra time and effort will help them do just that. This is juxtaposed with a “fixed mindset,” or the belief that our qualities are fixed traits that can’t be changed. Research suggests that adults with ADHD may tend toward a fixed mindset about their abilities but will more likely see success in reaching their goals if they can adopt a growth mindset (Burnette et al., 2020).

Recent research on brain plasticity confirms the ideas of a growth mindset. The brain is far more malleable that we imagined, and connectivity between neurons can change well into adulthood. With new experiences, neural networks can strengthen existing connections, grow new ones, and speed up transmission. The strategies you practice as a result of this book can literally grow your brain. Taken together, mindfully evaluating your cognitive behavioral process to evaluate what works (metacognition) and buying into the idea that your brain can still grow new circuits and pathways (growth mindset) will ultimately help you maintain overall forward progress on your objectives and goals.

GETTING BACK ON TRACK: EVALUATING WHAT WORKS

To engage in metacognitive strategies, using the Week 1 worksheet you created previously, attempt to follow through with your first week’s objectives, and then think back on your week and give yourself a score with an explanation. You may want to use a counselor, coach, or buddy to fully examine your behavior, as the inherent conundrum in studying metacognition remains that a deficit in metacognition may be hard to detect if people are asked to evaluate themselves, as they would not be able to do so realistically if they indeed have a deficit in metacognition (Nelson & Narens, 1994). To evaluate your strategies, follow this process:

- First, review the previous week’s goals and whether they were met.

- If your goals were not met, think about why you were unable to meet them and whether consequences were enforced.

- If your goals were not met and consequences were not enforced, think about why this occurred and what needs to be changed so that it will not happen again.

- If your goals were met, think about why you were able to do this and whether rewards were carried out.

- If your goals were met and rewards were carried out, think about why this occurred and what needs to happen so that you can continue to be successful.

- If your goals were met but rewards were not carried out, think about why this occurred and what needs to be changed so that you can follow through on rewards.

- After thinking about the previous week’s goals, decide on the following week’s goals as well as the rewards and consequences for meeting or not meeting each goal.

As an example, take Addison’s very first objective of her first week: Decide on a planner or calendar system to use for LTG planning and purchase. Imagine Addison spent a good 30 minutes online researching and finding a great planner, decided on one, and then forgot to order it. With only the ability to say yes or no all the way, Addison is forced to choose 100% failure on her first objective. This option is not good for her confidence, and it is not completely rational. To give a more accurate and encouraging picture of her accomplishments, one final column has been added to the objectives sheet for the user to “score” their performance (Exhibit 4.1). In Addison’s example, considering all that she did do, it might make sense to score herself an 8 out of 10, 80%, or some other version of grading her accomplishments. And telling yourself you got an 8 out of 10 feels a whole lot better than telling yourself you failed to complete your objective.

EXHIBIT 4.1. Evaluating Addison’s Week 1 Objectives

Addison’s Week #1 Objectives |

LTG # |

Due date |

Reward and/or consequence |

Start of Week #2: Score yourself and reflect. Did any thinking errors occur? How can you reframe them? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Decide on a planner or calendar system to use for LTG planning and purchase. |

1 |

Friday |

Reward: Decorate planner with favorite photos. Consequence: Decorate planner with embarrassing photos of myself. |

8 out of 10. I was successful in ordering but not in time for it to arrive by Friday. Thinking error: Ignored the good and focused on not having it in time. Reframe: I am proud that I researched, chose, and ordered it! |

Review phone contacts and flag friends whom I would like to connect with. |

3 |

Sunday |

Reward: Favorite TV show on Sunday evening with a glass of wine. Consequence: No makeup to work on Monday morning. |

4 out of 5. I got through the letter T but forgot to finish. |

Take photos of my bedroom and bring to next session to review and explore organizing options. |

2 |

Wednesday |

Reward: Buy a new pair of earrings. Consequence: Clean bathroom well, including floor and shower. |

Took photos and remembered I forgot to bring them on my way to session. Thinking error: Fortune Telling. I thought coach would be disappointed in me. Reframe: I don’t know how the coach will feel. She might actually be proud of me for making progress. 5 out of 10. |

Put note on bedroom mirror that says, “Is there another way to think about this?” to start encouraging reframing of negative thoughts. |

4 |

Wednesday |

Reward: Have Alexa play my “happy” playlist while I shower. Penalty: Unplug Alexa until I do it! |

100%!! |

Addison was able to reach many of her weekly objectives set during the first 2 weeks of treatment. By focusing on her overall success, she felt encouraged to feel good about her achievements and tie her behaviors to her feelings and cognitions. When she wasn’t completely successful, she reviewed what she had learned from her struggles and reminded herself that her mind would grow as a result. Because of the growth mindset and positive framing of her small initial successes, Addison began to feel encouraged about moving forward. By having her set and (mostly) meet small objectives in the beginning, her counselor helped her to increase the likelihood that she would be successful in reaching those objectives, and, as a result, Addison gained confidence in the process and her abilities. Still, she expressed some concern for her capacity to “keep the momentum going,” so her counselor kept this in mind and helped her to continue to experience success.

Every few weeks, Addison and her counselor looked back at her long-term goals (LTGs) and discussed where Addison felt she had and had not made progress and whether she was on track with her weekly objectives as far as reaching her goals. When examining your own goals and objectives, you may realize that you have been unrealistic with your expectations and need to tone them down. Or you may feel you could do more. Fortunately for Addison, she found her goals to be realistic and achievable. For those who are not as positive, it is important to continuously reevaluate the small steps that should be taken toward realizing a bigger goal and celebrate small achievements. In treatment sessions, modeling a problem-solving strategy is imperative. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) counselors and coaches must consistently review previous plans, determine which are workable, and help clients like Addison to adjust goals or behaviors as needed.

Now you try. Using Exhibit 4.2, evaluate your weekly objectives from the last chapter.

EXHIBIT 4.2. Try It! Evaluate Your Week 1 Objectives

Week #1 Objectives |

LTG # |

Due date |

Reward and/or consequence |

Start of Week #2: Score yourself and reflect. Did any thinking errors occur? How can you reframe them? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

QUICK TIP: DAILY LOG OF GOAL-RELATED ACTIVITIES

Another tool for gaining further insight into your behavior is the daily log of goal-related activities (Exhibit 4.3). To use it, choose one or two objectives during the week and then document your behavior in relation to those objectives. This daily log helps you engage in metacognitive from a growth mindset perspective.

EXHIBIT 4.3. Try It! Daily Log of Goal-Related Activities

Specific actions/behaviors I planned to follow through with today |

Specific steps I took toward following through with set plans |

What helped me follow through with set plans? |

Specific steps I did NOT take toward following through |

What obstacles prevented me from following through? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

THE ROLE OF FEAR

Often, adults with ADHD begin to unravel when they hit a roadblock or their motivation starts to fade. Fear sets in, and they lose their momentum. When it comes to setting and reaching goals, fear expresses itself as avoidance and the powerful urge to either delay performing a task or wait for its expiration so that it no longer has to be dealt with. There are two types of fear in terms of task completion: fear of failure and fear of success. Former Swedish soccer manager Sven Goran Eriksson once said, “The greatest barrier to success is the fear of failure.” He was half right. Fear of failure can render a perfectly capable person completely helpless and inoperative. When it comes to fear, the difference between successful people and unsuccessful people is their view of feedback. Successful people take criticism as constructive. They accept that mistakes are going to be made, and they try to make fewer the next time. Unsuccessful people view criticism as personal rejection, a permanent fixture that prevents them from moving forward. If you allow fear to prevent you from completing tasks, the cluster of avoided tasks will increase over time. As outstanding tasks mount, you may become resigned, depressed, and immobile.

What Sven Goran Eriksson should have said is, “The greatest barriers to success are the fear of failure and the fear of success.” Fear of success may seem silly to some, but it can be just as debilitating as a fear of failure. People commonly fear success because of how it may change them or their circumstances. Think of the phrase “It’s lonely at the top.” Success can be isolating. Success can also change others’ expectations of you. You may believe that once you have shown a certain aptitude, you will be expected to perform at this level from then on. For example, if you put forth your best effort to complete a project at work on time and to perfection, sacrificing sleep and nutrition, will your boss expect you to do this for every project? If that is your belief, you may think it is better just to give a consistent mediocre performance. Or perhaps you fear that you won’t be able to repeat your success so it’s better to never succeed in the first place.

If you think you may fall into one of these two categories, ask yourself, “What am I afraid of?” In fear-motivated behavior, it is necessary to identify the fear to begin with. For example, an adult with ADHD who has struggled to find a job over an extended period of time may develop a fear of being rejected yet again. A college student with ADHD may put off completing their class project because of a fear of obtaining a high grade that their parents would expect her to repeat. A client named Joel had set a goal of taking time to assist his wife with the care of their children on weekends. For three weekends straight, Joel wrote in his planner to take the kids to the park from 12:00 to 4:00 on Saturday afternoons. For 3 weeks straight, Joel returned to sessions admitting that he had watched football instead, while his wife had watched the kids. After his counselor encouraged him to engage in metacognition and take a thoughtful look at why he was unable to complete this objective, Joel admitted, “I’m afraid that if I spend one Saturday with the kids my wife will enjoy her time off so much, she’ll want me to take them every Saturday, and I’ll never watch another college football game again.” If you believe you may have a deep-seated fear that is sabotaging your efforts to move forward, it may be best to talk to a trained therapist or counselor. For milder cases of fear, the strategies in Chapter 1 on cognitive reframing will help.

Let’s get back to our case example. Eventually, Addison, who had been very successful for the first several weeks, was unable to follow through with one of her objectives. I acknowledged this but did not focus too much on it at first. Instead, I let Addison continue talking through her other objectives and congratulated her on her successes. It was important that Addison continue to celebrate the positive strides that she had made and not become discouraged with minor setbacks.

Only after discussing the other objectives did I bring up the uncompleted objective. A failed objective can be a very valuable learning experience. By facing her fear and admitting that she was unsuccessful, Addison saw that the “world won’t end” and that she could continue to persevere in the face of failure. Understanding that you don’t have to start from square one and that one failure does not undo all of your success can be one of the most valuable lessons learned when working toward your goals.

GAINING INSIGHT

Evaluating what works is critical to gaining insight into your behavior. Many ADHD counseling and coaching clients feel that gaining insight into their behavior is the most important aspect of the treatment process (Reaser, 2008). On completion of ADHD coaching, a client named Alicia stated, “I came in thinking I needed to change a certain set of behaviors, and we ended up going in a completely different direction. It was more the way I approached life and thought about things.” Henry, too, felt that the insights he learned were “kind of a missing link” in his progress.

This is a great time to stop and add some of the tools that you have found helpful thus far to your toolbox. Perhaps you’ve highlighted some ideas that have jumped out at you as you have been reading. Write each one on an index card or record it electronically and put it in your toolbox. Or maybe you have learned something in the objectives you have written for yourself so far like what you thought was one step turned out to be five and you should, therefore, be aware of this tendency going forward.

At the end of our time working together, Addison shared with me some of her final thoughts about the goal-setting process and how she would use her new skills moving forward:

I got a lot just from the process of writing things down and thinking about my behaviors. What I plan to do at this point is write my objectives on my calendar. For example, “pay bill by this day” or “complete my paper by this day.” I will pick a day and a time and a specific moment when it has to be done. Not just like, “oh, this week sometime” or “soon.” That way, I can’t put it off. Something else I think I’ll take from it is the steps. Specifically, here is how I start. Here is the next thing I do. And I like to check things off and make lists so that is kind of fun, almost. I feel like I’m getting somewhere. So, putting things in small little chunks will probably work for me going forward. And I’ll continue to do that.

Regarding rewards and consequences, Addison learned this about herself:

I found that rewards were better motivators for me and help me to keep pushing forward. When I penalize myself, I start to hear the negative voices of my parents and teachers, which isn’t healthy. By ignoring the little mistakes rather than making a big deal of them, I tend to be much more successful overall.

Several months later, Addison emailed me the following note:

Hi!

I hope you are doing well!

Some updates I thought I’d share: I graduated on Friday with my graphic design degree and received an academic award! I was in the top three in my class, can you believe it?! I’ve also maintained the organization of my home office. Today is my fourth date with a really great person I met through one of the friends I connected with during treatment. Most importantly, I believe in myself again and am working toward some new goals while referencing my tool box! Just thought I’d share and say thank you!!

—Addison

SUMMARY

Here are the important points you will want to take away from this chapter. Use the following checklist to note the areas you have thoroughly studied. Leave the box empty if it is an area you would like to come back to and review further.

- I have used metacognition to better understand my behavior.

- I can define a “growth mindset” versus a “fixed mindset” and explain how each impacts my success.

- I have asked myself specific questions about my plan in regard to what works and what doesn’t work for me.

- I have used the daily log of goal-related activities to get a clearer picture and further insight into my behavior.