CHAPTER 6

ENHANCING SOCIAL RELATIONSHIPS

I know I’m a handful but that’s why you have two hands.

—Author Unknown

One of the key tasks of adulthood is developing and maintaining social relationships. We begin as children learning about relationships from our parents, practice friendships throughout adolescence, and lay the groundwork for adult friendships and intimate relationships. Hopefully, we will find our “soul mate,” commit to a long-term relationship, and enjoy the benefits of a lasting relationship with that person. We will also continue to maintain and nurture our friendships, as they will provide enjoyable times and emotional support throughout the ups and downs of our lives. The symptoms associated with adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) can, at times, help a person to develop friendships, but they can also make long-term relationships a challenge. In this chapter, I discuss the ways that inattentiveness, hyperactivity, and distractibility can get in the way of your social relationships. Then, I discuss how executive functioning is important to relationships. We help you figure out if you are realistic in your self-perception of your social skills. The how-to part of this chapter gives you suggestions for paying attention in conversations and teaches you how to make a listening plan. I also give you a list of general tips to improve your social relationships. Start by taking this quiz to see if this is a chapter that will help you out.

QUIZ YOURSELF—DOES THIS SOUND LIKE YOU?

- Do you blurt out things that you later regret?

- Do you tend to interrupt others when having a conversation?

- Do others complain that you don’t listen or that you forget what they’ve told you?

- Does your spouse or roommate complain that your space is always a mess?

- Do you forget anniversaries and birthdays, or do you remember but can’t quite seem to get a card or gift in time?

- Do others complain because you are never on time for dates or planned activities?

- Do you frequently lose your temper over something minor?

- Are you accused of being self-centered, even though you don’t think this is true of you?

WHAT THE EXPERTS SAY

Research has suggested that, beginning in childhood, those with ADHD have a difficult time with peer relationships. Children with symptoms of hyperactivity and impulsivity tend to show aggressive and disruptive behaviors. Their social skills, particularly when it comes to making friends, can be poorly developed. They seem to overwhelm other children by being excessively intrusive, abrupt, and inappropriate. Why do these behaviors occur? The reason is not clear, but some researchers think that children with symptoms of hyperactivity have a need to seek sensation. When there is no stimulation in the environment, they need to create some. As a result, they look for social disruption rather than smooth social interactions. Alternatively, children with more symptoms of inattentiveness tend to be more anxious and shier and to withdraw from others, which can lead to being neglected (as opposed to actively being rejected). Regardless of the symptoms, children with ADHD are more likely to be rated by peers as less popular, and they often rate themselves as feeling lonely.

Do these early social difficulties disappear? Somewhat, but not entirely. Adults with ADHD tend to have many more problems with friends than those without the disorder (Young et al., 2009). Adults with ADHD can have difficulties in understanding social cues and don’t seem to attune their behavior to other people (Murphy, 2005). Hence, they can be perceived as rude or insensitive. They can also be described as moody and have frequent mood swings, often changing from happy to sad with little obvious provocation. Some partners report that those with ADHD have very low frustration tolerance and tend to anger easily. There is a fairly high co-occurrence of depression with ADHD, which can be a strain on social relationships (Murphy, 2005).

Adults with ADHD tend to outgrow their childhood symptoms of hyperactivity; however, the symptoms of inattention and impulsivity tend to remain and can be problematic. Research on ADHD and marriage has shown that the rates of getting married are not different for those with ADHD, but unfortunately, satisfaction with one’s marriage tends to be lower. There is also evidence that separation and divorce rates are higher. One research study found that women were more likely to be supportive of male partners with ADHD and tolerant of their symptoms (Eakin et al., 2004). Alternatively, men were more likely to divorce their spouse or leave the relationship when they were involved with a woman who had ADHD. Studies have shown that, in general, adults with ADHD feel that they get angry easier, have temper outbursts, break up relationships over trivial matters, and have difficulties managing finances that lead to marital troubles. They also feel that they have a harder time keeping friendships. Why is this? Many relationship and marital problems can be related to what we know about ADHD.

Let’s look at the three core symptoms of ADHD and see how each one of these can cause problems with different aspects of adult relationships. First, let’s talk about inattention. Relationships are all about communicating, which generally revolves around having a conversation. Conversations require that you pay attention to the other person. If you have ADHD, you can usually do this for a short period of time or when the subject is really interesting, but when conversations are long, you may find that you easily lose focus. It’s kind of like listening to that biology lecture in school. There just seem to be other things going on in your head, and those other things can easily crowd out the other person’s voice. This can cause the other person to get annoyed or frustrated with you and even accuse you of not paying attention on purpose, as if you had control over it. When we work with clients in treatment, we always ask about their social relations. Many clients admit that their friends or partners complain that they never listen. Many have actually been referred to us for exactly that reason. A partner has gotten fed up and insists that they come to see us to help them learn how to pay attention.

Second, let’s consider hyperactivity. Adults with ADHD do not display hyperactivity in the same obvious, “bouncing off the walls” way as children with the disorder. Still, individuals with ADHD often have a hard time with activities that require them to sit still or focus for long periods of time, even those activities that they enjoy. They may become restless and need to move from one activity to another fairly frequently. Their partners may interpret this as a sign that the individual with ADHD is bored with them or does not care enough to participate in an activity that’s important to them. A common complaint might run along the lines of, “I went jogging with you yesterday when I didn’t really feel like it. Can’t you even sit through lunch with my friends without constantly checking your voicemail and then insisting you need to leave before I’ve even finished eating?” Sometimes, complaints turn into some variation of, “If you cared about me, you wouldn’t act that way.” Again, the other person seems to imply that you have control over your behavior and that if you cared about the relationship, you would just shape up!

Finally, impulsivity can be a strain on relationships. Do others complain that you talk too much and they can never get in a word edgewise? Do you sometimes say something that you think is funny or clever and realize later that it really hurt someone’s feelings? Do you sometimes buy things on a whim or make decisions without really thinking them through? Does it seem like the expression “What was I thinking?” applies consistently and exclusively to you? These are symptoms of impulsivity and an inability to inhibit behaviors. There doesn’t seem to be any lag or thinking time between the impulse and the action. An idea or behavior pops into your head, and, before you consider it, it’s been said or done.

Each of these difficulties can be traced back to the core symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. However, without realizing this, your partner or friends can misattribute your behaviors to not caring about your relationship, lack of consideration, or just not trying hard enough. They can become critical and blaming. This, in turn, causes you to try and justify your behavior. No one wants to feel bad, and trying to protect your self-esteem is a natural thing. So, you react by being resentful, blaming the other, and being unwilling to take responsibility for disagreements or problems. Do you see a vicious cycle here? Many times, it’s just easier to give up on the relationship and move on, without really learning from it.

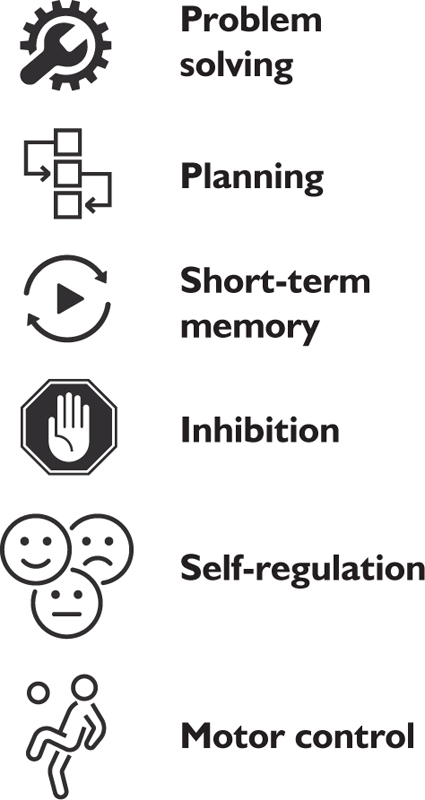

If we look at the science, we can begin to understand how difficulties in relationships make perfect sense. As I’ve stated previously, adults with ADHD have difficulties in areas that are referred to as executive functioning. Executive functioning can be thought of as the primary control center in the brain that underlies most of our behaviors. Executive functions can be compared with managers in a large business. They plan and delegate activities to personnel throughout the organization who get the different jobs done. These “jobs” include key activities such as problem solving, planning, short-term memory, inhibition, self-regulation, and motor control. When one or more of these basic jobs are not being carried out, difficulties can occur.

EXECUTIVE FUNCTIONING “JOBS”

Remember the previous quiz? Did you respond “yes” to blurting things out or interrupting? These behaviors would fall under the realm of inhibition, self-regulation, and motor control. How about forgetting things? This would fall under short-term memory. The concept of executive functioning is still being investigated. The exact categories change between different studies, with some scientists including additional functions. Also, it’s clear that not everyone with ADHD has deficits in all areas. One person with ADHD might have poor memory skills but be pretty good at inhibiting their motor impulsivity. Sometimes, this depends on whether you have the predominantly inattentive type of ADHD or the predominantly hyperactive–impulsive type of ADHD. However, executive functioning is a very important model in understanding ADHD and helps us explain how the “control center” in the brain can impact specific day-to-day behaviors that can have a tremendous impact on social relationships.

WHY IS BEING REALISTIC SO DIFFICULT?

There’s another mechanism called the positive illusory bias that has been studied in individuals with ADHD. This bias occurs when someone thinks they are better at doing something than is warranted by the evidence. For example, we frequently ask clients about driving a car. We ask them how many speeding tickets they’ve received, how many accidents they’ve been in, or if they’ve ever had their license taken away. We find that they are pretty good about answering these specific questions, which we call the evidence. Then, we ask them to give an overall rating of how good a driver they are. We refer to this as their self-description. We frequently find that they rate themselves as a very good driver, even though the evidence they’ve just given us doesn’t suggest that at all. We often find that the self-description is more positive than the evidence. We believe this type of responding is a characteristic of the positive illusory bias, in that they see themselves through rose-colored glasses. Research has supported this idea; those with ADHD are significantly more likely to give global self-ratings that are not supported by specific evidence. This can often happen in relationships. Adults with ADHD might really think that they are trying hard in a relationship, and so they are really blindsided when their partner criticizes them. Are they in denial, making things up, out of touch with reality? We don’t think so. We think they really believe what they are saying. Again, this disconnect between the evidence and the self-description seems to be a by-product of the executive functioning deficits, whereby those with ADHD just have difficulties with memory, sequencing, and logic. First, those with ADHD may not remember accurately what really happened or what they have done or said in the past. Second, they have a difficult time putting things in logical sequences. The result is a difficult time with self-appraisal.

Here’s another example of the sequencing difficulty. Adults with ADHD are frequently late for appointments, meetings, or classes. When asked to give an estimate of how long it takes them to do something—for example, get to class—they will give an estimate that is really not enough time. They might estimate 30 minutes. But if they are asked to estimate separately how long it takes to fix and eat breakfast (15 minutes), shower (10 minutes), get dressed (10 minutes), drive to campus (10 minutes), look for parking (5 minutes), and walk into their classroom (5 minutes) and the minutes are added up, the total is almost an hour. Are they intentionally misstating the time? No, of course not. But their executive-functioning deficits make it difficult for them to break down the task and do that sequencing all at once. So, they make a very global estimate that turns out to be inaccurate. Why does it seem to always be incorrect in the direction of underestimating time? Again, the reason is unclear. But there’s a good chance that the positive illusory bias comes into play again, and they really want to believe that they are able to do things quickly. Some researchers think that individuals with ADHD have gotten so much negative feedback that they try to cope with this by seeing themselves in a more positive light whenever possible. This self-protective behavior can be very adaptive. But you can see how this can have an impact on social relationships. Go back to Question 6 at the beginning of this chapter. Did you check “yes”? This difficulty in sequencing, along with a positive illusory bias, might help explain why you are frequently late for dates or planned activities.

CAN YOU RELATE TO THIS?

The following case describes a middle-aged couple, Fred and Eileen. Fred was diagnosed with ADHD in high school and is now 40. He reported no trouble with making friends, but he admitted to some trouble keeping friends. He had dated several young women in college and throughout his 20s, but the relationships never lasted long. Fred met Eileen through a dating app around his 35th birthday. While Fred was still living with roommates and spending money on entertainment, Eileen had saved and bought her first house with cash. Fred considered himself to be easygoing, fun-loving, and kind. He was extroverted and loved to party. He was always up for an adventure, such as learning to scuba dive, going extreme mountain biking, skiing a black slope his first time out, or taking a road trip with his buddies on a moment’s notice. Fred never had trouble finding friends to hang out with. When Eileen came along, he was sure she was “the one.” She had seemed immediately attracted to him, laughed at his zany humor, loved his sense of adventure, and told him he brought out the best in her. Eileen had confided that she was insecure about herself and couldn’t quite believe that someone like Fred would be interested in her. Fred admired Eileen’s stability. She kept him on track, kept him out of trouble, and was a wonderful listener.

After 3 years of marriage and the birth of their first child, Eileen sat Fred down at the dinner table and proceeded to tell him how she was “frustrated by his constant lying and manipulation” and that their relationship was “in peril.” After his initial confusion over Eileen’s statement, David managed to sputter, “But our relationship is fantastic! I never lie to you!” Eileen burst into tears and, between sobs, replied, “Of course, you think it’s fantastic! You weasel your way out of everything, and I am left to pick up the pieces!” She started with a long list of complaints. Fred thought only about himself. He forgot everything she told him, even really important things like her best friend’s baby shower that she had reminded him about five times. When he did remember to show up, he was always at least a half an hour late. It was like having a second child. She was tired of having to remind him about everything. She couldn’t rely on him to do anything for the baby. He was on his fourth job since college and used up half of her savings on business ventures that went nowhere. He always got excited starting new things, but when the excitement wore off, his enthusiasm fizzled. At home, too, he would start numerous projects but never finish them.

Eileen continued, “And you never pay any attention when I try to work on things! I’ve told you how much it upsets me when you forget a date or are super late, and you always promise to do better. But it never lasts more than a week! Remember on Friday, you promised to come home from work early to watch the baby so I could see my friends? I had to call you a half hour after you should have been home. And then, on top of it, you lie and say you had to work late!”

Fred countered, “I didn’t lie. I was working.”

Eileen jumped in, “Because you had to or because you forgot about me and your promise?”

As Eileen continued, Fred felt himself slipping away. He couldn’t focus on all this right now, and he tried to listen to her while thinking that he needed to call Sam and see if he wanted to go kayaking. Miraculously, Fred’s phone rang right at that moment, and he answered it quickly. It was one of the guys from work. Fred listened a minute, barely registering as Eileen stormed out of the room. When he was finished with the phone call, he thought about going after her but decided it would be useless. He would just mess things up and make it worse. Besides, she was being ridiculously unfair. Instead, he called his buddy Sam and suggested they get some dinner; anywhere was fine with Fred. He would deal with Eileen later.

Fred went to a bar with Sam, initially in a horrible mood. Over dinner, he told Sam about Eileen’s blowup, emphasizing how unreasonable Eileen was. Sam agreed. Fred felt much better, and, by the time they left the bar, he had pretty much returned to his normal cheerful state. Back at home, Eileen was cool and remote. Fred sensed that the conversation was not going well but proceeded to tell Eileen a long story about a funny incident at the restaurant that he was sure would make her laugh. Eileen was not amused, and, in fact, there was a long silence at the place where he expected her to laugh.

“What’s wrong?” he asked. “Are you still upset about earlier?” Eileen retorted that of course she was still upset. She couldn’t believe that he had gone out with Sam instead, but, of course, she retorted, that was just like him. She was clearly angry, and Fred felt himself losing control in return. He was trying to be pleasant, so what more did she want? He was doing all the work here; maybe it just wasn’t worth it. He was no good at relationships, and he always screwed them up. He was tired of constantly being criticized and nagged. He never got credit for the good things he did. Why bother trying to fix it?

COMMON SOCIAL TRAITS OF ADULTS WITH ADHD

This scenario illustrates many issues seen in the adult social relationships of individuals with ADHD. Fred has many positive traits and finds it fairly easy to make friends. His friendliness and outgoing nature are wonderful attributes. He is adventuresome and meets lots of new people through his many activities. He has dated quite a bit, and each new relationship starts out well. However, similar patterns soon emerge. Fred’s partners have common complaints: lack of attention, inability to finish things or taking an inordinately long time, forgetfulness, and chronic lateness. His communication skills are poorly developed, especially when it comes to conflict and resolving arguments. Because things are not generally resolved, old arguments simmer, just below the surface, and erupt easily. Arguments become more and more common, and Fred finds ways to escape, such as avoidance or hanging with his buddies. It is invariably a tearful parting, with the partner claiming to love him but just not being able to put up with his many issues. Although Eileen was able to deal with Fred’s shortcomings prior to caring for a child, his marriage was now headed for a similar demise.

Take a look at the executive-functioning tasks described previously. You should be able to see how many of these can be involved in the difficulties Fred is experiencing. Smoothly running control centers for problem solving, planning, short-term memory, inhibition, and self-regulation would have helped Fred tremendously as he attempted to respond to some of Eileen’s needs. So, let’s take a look next at how we can use some of those skills in a critical area of relationships.

GETTING BACK ON TRACK: BETTER COMMUNICATION SKILLS

Communication is a key to building good relationships. It is the foundation for getting to know someone, sharing experiences, and establishing the rules for how you will relate to one another. When you first meet someone, you quickly learn enough about the other to decide whether things will “click” and whether this is someone you might want to be friends with. How does that happen? How do you decide that some people are worth pursuing as friends and others are not? Think about your current friends. Think back to when you first met them and what led to you becoming friends with them. Maybe it was shared interests or merely being in the same situation at the same time. Maybe it was sports, college, a job, church, a club, or activity, or maybe you just met through common acquaintances. What was your common link? Did you actively decide that you wanted to pursue this person as a friend, or did you just drift into a relationship? No matter what the circumstances, your ability to communicate likely had an impact on your continuing relationship.

PAYING ATTENTION IN CONVERSATIONS

Think about the types of things you need to communicate with your partner or friends. Possibilities include household chores, social events, day-to-day activities in your life, gossip, or feelings. You may also need to learn how to do damage control when you’ve upset someone. When you have conversations, try to think about your communication style. Most people can classify themselves generally as a talker or a listener. Many times, individuals with ADHD are accused of talking too much and not paying attention. So, let’s focus on the skill of paying attention.

Step 1: Identify and Gather Evidence About the Issue

First, let’s just think about communication in general for a minute and divide this up into its positive and negative components. The positive aspect of your communication style might be that you are entertaining, funny, enjoyable to be around, or, perhaps, even the life of the party. You may be good at telling stories, very creative and dramatic, and have a great sense of fun and adventure. People may be attracted to you and enjoy being around you. But do you ever get the sense that you are alone in the midst of people? Do you sometimes feel that your relationships are superficial? There may be a negative aspect of your outgoing personality. You might be neglecting to let others talk and not paying attention to the needs of others, and so, your relationships might be a bit one-sided.

So, as a first step, let’s gather some evidence. Pick two or three situations during the coming week. Have “normal” conversations. Don’t do anything different except try to reflect on the conversations once you’ve finished. Each time, after the conversation is over, think about the definition of positive listening below and rank yourself on a scale of 1 to 5. Here is the definition of positive listening:

I paid attention. I can repeat specifics of the conversation. I remember specific things the other person asked me to do. I remember details, times, and dates of any plans made. I listened as much as I talked. I focused. My mind didn’t drift. I learned something about the other person such as something they did, how they felt, or something they want me to do. I think this conversation deepened my relationship with this person.

Now give yourself a 1-to-5 rating for positive listening, as follows, for how you listened in general, across the 2 to 3 conversations you monitored.

I think that, in general, I listened:

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

Not at all |

Somewhat |

Pretty Good |

Good |

Really Well |

Now, let’s try getting some outside confirmation. Think about your key relationships. Perhaps check out your rating by asking at least one other person to do rate you as well. You may not realize how your listening skills come across to others. Is your rating the same as the other person’s? Go back and read the definition of positive listening. What specific parts of the definition tend to be challenges for you? What parts do you think you do pretty well?

Step 2: Commit to Change

Using your previous data gathering, think about whether this is an area you want to change. The more you think you need to change, are motivated to change, and commit to wanting to change, the easier and more successful you will be. Did you or your friend identify any specific areas that might be a problem? Think of examples of how not paying attention in conversations might have gotten you in trouble with friends. Visualize a different you. How would that look? This can be part of your motivation to change. Would it make your life better? Would it improve your relationships? Would it improve how you think about yourself? What positive things might happen to your relationships if you became a better listener? Are there situations in which you do attend that have turned out well?

After thinking through these questions, make a commitment to changing your listening behavior. Write down some specific things you want to accomplish. Some can be very specific; others can be a little more general. Here are some examples:

- I want to remember appointments and plans I’ve made with my husband.

- I want my friends to know I care about their problems.

- I want my friends to think I’m a good listener.

- I don’t want to have to be reminded again and again of things people tell me.

Write your intended accomplishments in Exhibit 6.1. Prioritize them. Put the most important one first, as you are going to work on them one at a time. By writing these down, you have established a commitment to change. If you’re like many individuals with ADHD, the how-to is not usually the biggest obstacle. You’re probably pretty bright, and it’s probably pretty easy for you to identify areas and know that change is needed. It’s the motivation part that can be difficult. That’s why Step 2 of this exercise is so important. You’re probably used to people telling you what your problems are and how to fix them. You probably have lots of experience with parents or teachers giving you direction and being in charge of your “personality makeover.” But unless you take charge of the things you want to change, it will always be someone else’s responsibility, and you will just be the one who’s taking orders. By making up the orders and giving them to yourself, your motivation to change will increase dramatically.

EXHIBIT 6.1. Try It! Intended Accomplishments

1. _____________________________________________________

2. _____________________________________________________

3. _____________________________________________________

4. _____________________________________________________

5. _____________________________________________________

Step 3: Make a Listening Plan

Let’s start with the first item on your listening goals. First, you need to decide the best method for you to describe, chart, and remember your plan. You might choose to write it on a piece of paper and tape it to your bathroom mirror, you might write it on a whiteboard on your refrigerator, you might put it in a notebook that you review daily, or you might keep it on a note program in your laptop or phone. The only requirement is that you write it somewhere you can review daily. We’ll do a sample here, and you can model yours after that. For the sample, we’re going to choose the goal “I want to remember appointments and plans I’ve made with my wife.” We’re going to write the goal at the top of a piece of paper, and the paper is going to go on the bathroom mirror. Look at the sample listening plan provided in this chapter and fill in your own goal on your own plan.

Next, we’ll fill in a 1-week objective. This should be something we can accomplish in a 1-week time frame that relates to our overall goal. For our first attempt, it should be something we really think we can accomplish. We want to start fairly easily so we don’t get discouraged right off the bat. Our 1-week objective will be “I want to remember one important activity I’ve planned with my wife, and stick to it.” Choose your 1-week objective and write it down. It should be something that leads directly to your overall goal. Sometimes, your overall goal can be accomplished in a single week, so the goal and the 1-week objective will be the same thing. But, usually, it will take more than a single 1-week objective to reach your goal.

Next, we’ll fill in some short-term or daily objectives. These are the steps we need to take during the week that will lead up to the 1-week objective. Try to make them very specific, with each of them being a specific behavior. For example, we have four: writing down our activity and putting it in our planner, checking it daily, confirming the activity the day before, and setting a reminder alarm.

Finally, we’ll put in some rewards and consequences. These are really important, so don’t skimp here. If you have ADHD, you can come up with the goal and the behaviors easily. It’s the follow-through that gets you in trouble. You need to be motivated—so, let’s digress just a moment and review some ideas from Chapter 2 on motivation before we finish our listening plan.

Here, we will expand on the idea of motivation, as presented in Chapter 2, and explain how it relates to relationships. Motivation can be defined as an internal state or condition that energizes someone to engage in a behavior. The source of the motivation can be either external (I’ll do this job, so I’ll receive a paycheck on Friday) or internal (I’ll play the piano because I love the way it relaxes me). Motivation can also be described as positive, somewhat like a reward (the paycheck), or negative, such as avoiding a punishment (I’ll drive the speed limit so I don’t get a speeding ticket).

Research has shown that those with ADHD exhibit very different motivational styles. They tend to need more immediate motivation, and they seem to have a harder time creating internal motivation. Repetitive tasks are especially difficult without motivation, and individuals with ADHD are more likely to just stop or quit a task. Some scientists have concluded that those with ADHD have poorer general ability or cognitive skills than those without ADHD. But this is not entirely true. Many times, if the scientists actually measure the motivational level of participants in these studies, they tend to find that it’s the lack of motivation, rather than the lack of ability, that sets the ADHD participants apart from the non-ADHD participants. Why is this? Think back to the previous discussion on executive functioning. Motivation requires good short-term memory to keep in mind what the reward will be, it requires the ability to bridge delays and not lose focus, it requires attention to the task at hand, and it requires an internal self-talk that helps to regulate one’s behavior. All of these capabilities can be affected by executive-functioning deficits. So, the end result is that you have a very difficult time with self-motivation. You know how to do a task; you just can’t manage the follow-through.

If you think back to when you were in elementary or high school, you can probably remember times when parents or teachers served as your external motivators. Perhaps you were involved in a reward system in which you received points and then specific rewards for completing tasks—constantly reminded to complete your homework. Or maybe you were forced to study on a particular schedule or required to take assignment check-off sheets back and forth between home and school. Did you feel like you frequently had a parent or teacher looking over your shoulder and prodding (or perhaps nagging) you to do things? If so, you probably got used to this kind of external motivation (both to gain positive rewards and to avoid negative consequences). When you went away to college or lived on your own for the first time, did you have a difficult time providing that motivation for yourself? It probably felt great at first to be in charge of your own life, but you probably realized at some point that self-motivation is a tough thing for individuals with ADHD. Let’s get back to our listening plan and work on providing the motivation you need to complete the plan.

Look at the motivation section of the sample listening plan in Exhibit 6.2. You’ll see five motivators listed there. Notice that some are internal and some are external. You’ll also notice that some are positive and some involve avoiding negative consequences. You’ll need to experiment to see what types work best for you. The motivation that might work best for other people may have no effect on you. Some people reward themselves with money, shopping, watching TV, food, naps, exercise, trips, going out, checking Facebook, or just spending time on the internet. Others do things just because they know they will feel a sense of satisfaction from having done something well or correctly, but this may be difficult for you as an adult with ADHD. Finally, there are many negative reinforcements, many of which involve not disappointing someone else. It can be helpful to write several motivators on your plan so that if one doesn’t work, the others might. Look back over them and see if you can identify them as internal and external. Also try to identify positive rewards versus avoidance of negative consequences. Did you seem to have a preference for one particular type? It may be helpful to use your list of rewards and consequences from Chapter 2. Try the plan for a week.

EXHIBIT 6.2. Sample Listening Plan

|

Goal I want to remember appointments and plans I’ve made with my partner. 1-Week Objective I want to remember one important activity I’ve planned with my partner and stick to it. Short-Term Objectives 1. I want to write down our activity in my appointment book. 2. I want to review my appointment book every night right before I go to bed. 3. I want to review the activity with my partner the day before, and let them know I’ve remembered it. 4. The day of our activity, I want to put a reminder in my cell phone, and have it beep me 10 minutes before I need to start. Motivation 1. My partner will be happy with me (external positive result). 2. I’ll feel better about myself (internal positive result). 3. I’ll also reward myself by setting aside $10 and spending it on anything I want if I meet my 1-week goal (external positive result). 4. I’ll penalize myself by not watching American Idol on TV next week if I don’t follow through on my plan (external negative result). 5. My partner and I will get in an argument if I don’t follow through (external negative result). Modify Plan I forgot the planned activity with my partner. I reviewed this list to see which thing went wrong. I put the activity in my calendar, but then didn’t check it or do anything else on the plan. I bought flowers, apologized, and showed my plan to let them know I’m trying. I’m doing the same plan next week, but, this time, I’m putting a big reminder on my laptop that says LOOK AT YOUR CALENDAR BEFORE YOU CHECK EMAIL. I’m also changing my rewards and putting in some more external rewards. |

Step 4: Evaluate and Modify

How did the plan work? If you were successful, what things seemed to make it work? Build on those things and proceed to your second goal, filling in all the steps the same way you did for your first goal. If you were not successful, what were the obstacles? Was the goal too difficult to expect immediate success? What do you need to change? The objectives? The motivators? Don’t give up. Think this through, talk with the person or persons involved in the plan, and see if you can get some feedback from them. They might have a very different perspective from yours. Modify and redo the plan, and try it for another week. Just working on the plan, whether or not you are immediately successful, will help you to think through your behaviors. Remember, this is under your control, and just the process of going through the steps can help train your mind to eventually do this more naturally. Ultimately, you want to reach the place where you’re doing automatically what your mom or teachers did for you in terms of making plans and encouraging you to be motivated. That’s what self-regulation is all about. And by letting important people in your life know that you are taking active steps to improve your relationships, they will perceive you differently. They might let go of that misperception that you don’t care or you’re not willing to change.

QUICK TIPS: IMPROVING SOCIAL RELATIONSHIPS

After reading this chapter, you might want to do some additional work on your own. Here are some additional tips:

- Make a list of your positive traits. There are lots of reasons why others like you. Focus on those!

- When talking, look the other person directly in the eye. It will help you to focus on what they are saying.

- Practice repeating back what someone has just said to you in a conversation (“So, you’re worried that you might be fired because the boss is jealous of your skills?”). This will help you focus on the conversation, remember what’s important to the other person, and let that person know you are listening.

- Pay attention to body language. Get used to guessing what someone is “saying” when they blink, cross their legs, tighten their lips, fold their arms, laugh nervously, look away, squint, or suddenly quit talking.

- Try to stop what you’re doing when someone starts talking to you. Don’t look at the computer, read the paper, or watch TV while trying to have a conversation.

- Make a conscious effort to stop talking regularly in a conversation and let the other person have a turn. Learn to ask questions to draw the other person out.

- Try to look for natural pauses in a conversation before you jump in. At the very least, wait until the end of the sentence.

- Avoid making major decisions without doing at least one of the following: wait overnight, make a list of pros and cons, or check out your plan with someone else.

- When you start a household task and think you’re finished, ask yourself, “Am I really done? Did I put away my stuff? Clean up after myself? Put things back where they belong?”

- Always try to add appointments, dates, anniversaries, meetings, and tasks in a calendar and check this daily.

- When figuring out how long it will take you to get somewhere, avoid being late by breaking down your estimate into pieces (getting ready, driving, stopping for gas, or parking).

- Be aware that your partner, spouse, or friends can’t read your mind. Tell them specifically what you want or need or mean.

- Do nice things for the important people in your life.

- Frequently remind yourself of your spouse’s or partner’s positive qualities. Either write them down in a journal or actually tell them.

- Develop interests and passions. You’ll be much more enjoyable in a relationship if you like your life and don’t depend on your partner to make you happy.

SUMMARY

Here are the important points you will want to take away from this chapter. Use the following checklist to note the areas you have thoroughly studied. Leave the box empty if it is an area you would like to come back to and review further.

- I understand the areas of difficulty in my social relationships and how ADHD impacts my social behavior.

- I can appreciate how the positive illusory bias might help explain why I am not always realistic or accurate in my self-appraisals.

- I have practiced positive listening and paying attention.

- I have learned many brief tips that can be especially helpful in improving social relationships.