Jerash, Irbid & the Jordan Valley جرش & اربد & غور الاردن

Jerash

Ajloun

Irbid

Abila (Quwayliba)

Yarmouk Battleground

The Jordan Valley

Mukheiba

Umm Qais (Gadara)

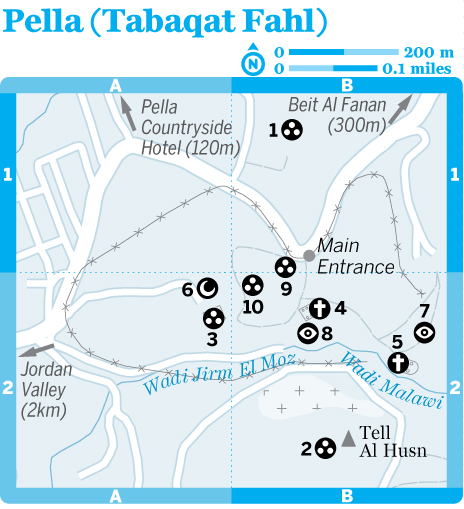

Pella (Tabaqat Fahl)

Salt

Jerash, Irbid & the Jordan Valley جرش & اربد & غور الاردن

Why Go?

The north of Jordan is sometimes overlooked by visitors, but this is a region rich in ancient ruins and biblical associations, all set in rolling countryside that’s ablaze with wildflowers in springtime.

The epic Roman city of Jerash is the north’s big hitter, a world-class destination without the crowds. Its contemporary, Gadara in Umm Qais, is smaller but has a tremendous setting overlooking the Sea of Galilee in Israel and the Palestinian Territories. Even better, Umm Qais is at the forefront of Jordan’s community-tourism scene, with everything from hiking and cooking classes to beekeeping on offer.

Ajloun Castle, atop an imposing hill, and the well-preserved Ottoman town of Salt offer insights into Jordan’s Islamic history, while you can get close to nature at Ajloun Forest Reserve, and hike the paths of the locally run Al Ayoun Trail, sleeping in village homestays to meet the people of this fascinating area.

When to Go

A A wonderful time to visit the northern part of Jordan is in spring (March to mid-May), when the black iris, the country’s national flower, makes a shy appearance along roadsides and a profusion of knee-high wildflowers spills across the semi-arid hillsides.

A For culture vultures, the hot summer months of July and August bring music and poetry to Jerash’s Roman ruins during the town’s Festival of Culture & Arts.

A From early November to January, subtropical fruits ripen in the Jordan Valley, while the region’s hill towns shiver through winter.

Jerash, Irbid & the Jordan Valley Highlights

1 Jerash Wandering the colonnaded streets and admiring the impressive theatres of a Roman provincial city, one of the most spectacularly well-preserved such sites in the Middle East.

2 Ajloun Forest Reserve Hiking along shady trails in one of the prettiest nature reserves in the country.

3 Ajloun Castle Enjoying the sweeping views from this dramatic hilltop castle, one of Jordan’s most impressive Islamic structures.

4 Umm Qais Taking in Roman ruins and enjoying the town’s community-tourism projects, from cooking classes and beekeeping to hiking and mountain biking.

5 Al Ayoun Trail Walking through the countryside along this locally run hiking trail and sleeping at village homestays.

6 Salt Ambling by traditional Ottoman houses in this souq town close to Amman.

History

The name ‘Gilead’ crops up from time to time in northwestern Jordan. This was the biblical name of the region, defined by the sculpting waters of the Yarmouk River to the north and the once-mighty Jordan River to the west. The hills of Gilead have been occupied since antiquity and were home to the Roman Decapolis. Largely established during the Hellenistic period, these city states flourished along the boundaries of the Greek and Semitic lands. The Romans transformed them into powerful trading centres – the torch-bearers of Roman culture at the furthest reaches of the empire.

If you’re wondering where these cities are today, chances are you’re walking on them. Northern Jordan is the most densely populated area in the country, home to the major urban centre of Irbid as well as dozens of small towns and villages that have largely engulfed many of the ancient sites. With a bit of amateur investigation, it’s easy to make out the tells (mounds) and archaeological remains of the Decapolis, scattered among Gilead’s rolling hills. If you haven’t the time or inclination for such sleuthing, head for Umm Qais (Gadara), Pella and especially Jerash, where there are enough clues among the standing columns, amphitheatres and mosaic floors to conjure the full pomp and splendour of the Roman past.

Nature Reserves

There are two reserves in the north of Jordan, both encompassing rare woodland. Ajloun Forest Reserve is the more developed of the two, with excellent hiking trails and accommodation options. Dibeen Forest Reserve is a popular spot for weekend picnics. Not strictly a nature reserve, but worth checking out, is the Royal Botanic Garden at Rumman.

8Dangers & Annoyances

This region is bordered by Israel and the Palestinian Territories to the west and by Syria to the north. Given the sensitivity of relations between these countries, a bit of discretion is advised when travelling near the Yarmouk or Jordan Valleys. There are many checkpoints, particularly around the convergence of those two valleys near Umm Qais, so it is imperative to carry your passport and, if driving, your licence and car-rental details. Don’t hike too close to either border. Avoid taking photographs near the border area – this includes photographing the Jordan River near checkpoints.

8Getting There & Away

Amman is the gateway to the north, so most public transport from other regions transits through the capital, though there are connections from Madaba and Aqaba directly to Irbid. There are two border crossings in the north with public transport to Israel and the Palestinian Territories – the King Hussein (Allenby) Bridge and the Sheikh Hussein (Jordan) Bridge. It is not possible (or safe) to cross into Syria. By car, you can enter the region via Jerash from Amman or along the Jordan Valley from the Dead Sea.

8Getting Around

Compared with other parts of Jordan, the north is well served by public transport. Minibuses link most towns and villages (and the main city of Irbid), and run at irregular intervals along the Jordan Valley. A bit of patience is required as you wait for buses to fill up, and you can forget trying to establish the ‘correct fare’ (however, no journey in the north is likely to cost more than JD1). Driving in the region is very rewarding, but it requires a few navigational skills, as promising rural roads often lead to dead ends because of steep-sided wadis.

Shuneh Al Janubiyyeh is a junction for public transport along the Jordan Valley and the King Hussein Bridge, as well as for the Dead Sea.

Jerash & Around

Often referred to as the ‘Pompeii of Asia’, the ruins at Jerash (known in Roman times as Gerasa) are one of Jordan’s major attractions, and one of the Middle East’s best examples of a Roman provincial city. Remarkably well preserved through the centuries by the dry desert air, Jerash cannot fail to impress.

Although the ruins are the undoubted key attraction in the area, there is more to Jerash (which also comprises a thriving modern town) and the surrounding area than just the ruins. Nearby Ajloun, for instance, has a grand castle and offers hiking trails, picnic opportunities, community engagement and places to buy fresh fruit from the surrounding hillside orchards. As such, although Jerash is usually visited as a day trip from Amman, there’s more than enough of interest in the area to warrant at least one overnight stop.

Jerash جرش

![]() %02 / Pop 50,750 / Elev 618m

%02 / Pop 50,750 / Elev 618m

Arriving in the modern town of Jerash, with its provincial streets and small market gardens, you see little to suggest its illustrious past. But the moment you cross from the new town into the ancient city, its boundary marked by the imposing Hadrian’s Arch, it becomes apparent that this was once no ordinary backwater but a city of great wealth and importance.

While the Middle East contains other surviving Roman cities that boast similar architectural treasures, the ancient ruins at Jerash are famous for their remarkable state of preservation. Enough structures remain intact for archaeologists and historians, and even casual visitors, to piece together ancient life under the rule of an emperor.

History

Although inhabited from Neolithic times and settled as a town during the reign of Alexander the Great (333 BC), Jerash was largely a Roman creation, and the well-preserved remains of all the classic Roman structures – forum, cardo maximus, hippodrome, nymphaeum – are easily distinguishable among the ruins.

Following Roman general Pompey’s conquest of the region in 64 BC, Gerasa became part of the Roman province of Syria and then a city of the Decapolis. Over the next two centuries, trade with the Nabataeans (of Petra fame) flourished, and the city grew extremely wealthy thanks to local agriculture and iron-ore mining. In the 1st century AD the city was remodelled on the grid system, with a colonnaded main north–south street (the cardo maximus – one of the great highlights of the site today) intersected by two side streets running east–west.

The city was further enhanced in AD 106 under Emperor Trajan, and the triumphal arch at the far southern end of the city (through which the site is accessed today) was constructed in 129 to mark the important occasion of Emperor Hadrian’s visit. Jerash’s fortunes peaked around the beginning of the 3rd century, when it attained the rank of colony and boasted a population of 15,000 to 20,000 inhabitants.

The city declined following a devastating earthquake in 747, and its population shrank to about a quarter of its former size. Apart from a brief occupation by a Crusader garrison in the 12th century, the city was completely deserted until the arrival of the Circassians from Russia in 1878. The site’s archaeological importance was quickly recognised, sparking more than a century of excavation and restoration and the revival of a new town on the eastern flank of the ruins.

1Sights

Jerash is cleaved in two by a deep, cultivated wadi. Today, as in the days of the Romans, the bulk of the town’s inhabitants live on the eastern side. The walled city on the western side, graced with grand public monuments, baths and fountains, was reserved for administrative, commercial, civic and religious activities. The two were once linked by causeways and processional paths, and magnificent gates marked the entrance. Today, access to the remains of this walled city is through the most southerly gate, known as Hadrian’s Arch or the Arch of Triumph. There’s a ticket office where you can also buy souvenirs, sunhats and cold drinks.

The site covers a huge area and can seem daunting at first, especially as there’s virtually no signage. To help the ruins come alive, engage one of the knowledgeable guides (JD20) at the ticket checkpoint to help you navigate the main complex. Walking at a leisurely pace, and allowing time for sitting on a fallen column and enjoying the spectacular views, you can visit the main ruins in a minimum of three to four hours.

Roman Ruins of JerashArchaeological Site

(map Google map; JD8, with Jordan Pass free; ![]() h8am-4.30pm Oct-Apr, to 7pm May-Sep)

h8am-4.30pm Oct-Apr, to 7pm May-Sep)

The ruined city of Jerash is Jordan’s largest and most interesting Roman site, and a major tourist drawcard. Its imposing ceremonial gates, colonnaded avenues, temples and theatres all speak to the time when this was an important imperial centre. Even the most casual fan of archaeology will enjoy a half-day at the site – but take a hat and sunscreen in the warmer months, as the exposed ruins can be very hot to explore.

map Google map; There’s no better way of gaining a sense of the pomp and splendour of Rome than walking through the triumphal, 13m-tall Hadrian’s Arch at the entrance to Jerash, built to honour the visiting emperor. From here you can see a honey-coloured assortment of columns and walls, some delicately carved with acanthus leaves, some solid and practical, extending all the way to a pale view of hills in the distance – just as the Roman architects intended.

The gateway was originally twice this height and encompassed three enormous wooden doors.

WORTH A TRIP

JORDAN’S ROYAL BOTANIC GARDEN

Aiming to showcase Jordan’s surprisingly varied flora, the new Royal Botanic Garden (RBG; www.royalbotanicgarden.org; Rumman) highlights best practice in habitat conservation. The site, which overlooks the King Talal Dam, spreads over 180 hectares, with a variation in elevation of 300m, allowing it to reproduce Jordan’s main habitat zones – pine forest, oak forest, juniper forest, the Jordan Valley and freshwater wadi. Check the website for access details, as the garden only erratically opens to the public.

map Google map; Dedicated to Artemis, the goddess of hunting and fertility and the daughter of Zeus and Leto, this temple was built between AD 150 and 170, and flanked by 12 elaborately carved Corinthian columns (11 still stand). The construction is particularly impressive given that large vaults, housing temple treasure, had to be built to the north and south to make the courtyard level. The whole building was once clad in marble, and prized statues of Artemis would have adorned the niches.

If you visit on a partly cloudy day, you’re in for a treat, as the sandstone pillars of the temple light up like bars of liquid gold each time the sun comes out. It’s a magical sight, and magic – or a sense of the world beyond – was exactly what the architects of this gem of a building would have been trying to capture in their design.

Alas, the edict of Theodorius in AD 386, permitting the dismantling of pagan temples, led to the demise of this once-grand edifice, as it was picked apart for materials to construct churches. The Byzantines later converted the site to an artisan workshop for kitchenware and crockery. In the 12th century the structure was temporarily brought back to life as an Arab fortification, only to be destroyed by the Crusaders.

If your energy is starting to flag, this is a good place to turn back. You can descend through the temple’s gateway, the propylaeum. If you want to get a sense of the complete extent of Jerash, head towards the North Gate for further views.

map Google map; Whatever the light and whatever the weather, the forum, with its organ-pipe columns arranged around an unusual oval-shaped plaza, is always breathtaking. It’s one of Jerash’s undisputed highlights. This immense space (90m long and 80m at its widest point) lies in the heart of the city, linking the main thoroughfare (the cardo maximus;) with the Temple of Zeus. It served as a marketplace and the main locus of the city’s social and political life.

Today it still draws crowds, with Jordanian families picnicking and site guards napping among the columns. And what superb columns they are! Constructed in the middle of the 1st century AD, the forum is surrounded by 56 unfluted Ionic columns, each made from four solid cuts of stone that appear double in number because of their shadow. The plaza itself is just as spectacular, paved with extremely high-quality limestone slabs. The slabs, which increase in size as they radiate from the middle, create a sense of vortex that draws your eye to the centre point. To appreciate this effect fully you need an aerial view, which can be gained from climbing the steps to the Temple of Zeus.

map Google map; As you enter the South Theatre through a wooden door between the arches, there’s little to suggest the treasure encased by the plain exterior. But then you emerge into the upper seating area… Built between AD 81 and 96 and once housing 5000 spectators in its two storeys of seating (only one tier of which remains), the theatre is almost perfect.

Sit in row 30 of the 32 rows of seats (if you can read the Greek numbers) and you’ll see how the elaborately decorated stage is just a foreground for the backdrop of ancient and modern Jerash. The light at sunset melts the stage surface. Cue music? That’s provided by the visitors who whisper experimental choruses and the members of the Jordanian Scottish bagpipe band who, with less subtlety, blast sporadic tunes to the four winds to illustrate the excellent acoustics.

The theatre comes into its own during the Jerash Festival of Culture & Arts, when it proves as worthy a venue today as it was for the ancients 2000 years ago.

map Google map; Though most of it has collapsed, this temple has imposing 15m-high columns that are some of Jerash’s most dramatic. The thick walls of the sanctum still stand, giving a clear view of how the original temple would have looked in its prime.

The tumble of columns in front of the temple speak to the destructive power of the earthquake that levelled Jerash in the 8th century.

THE DECAPOLIS

The Roman commercial cities within modern Jordan, Syria, and Israel and the Palestinian Territories became known collectively as the Decapolis in the 1st century AD. Despite the etymology of the word, it seems that the Decapolis consisted of more than 10 cities, and possibly as many as 18. The league of cities served to unite Roman possessions and to enhance commerce in the region. In Jordan, the main Decapolis cities were Philadelphia (Amman), Gadara (Umm Qais), Gerasa (Jerash) and Pella (Taqabat Fil), and possibly Abila (Qweilbeh) and Capitolias (Beit Ras, near Irbid).

Rome helped facilitate the growth of the Decapolis by granting the cities a measure of political autonomy within the protective sphere of Rome. Each city operated more like a city state, maintaining jurisdiction over the surrounding countryside and even minting its own coins. Indeed, coins from Decapolis cities often used words such as ‘autonomous’, ‘free’ and ‘sovereign’ to emphasise their self-governing status.

The cities may have enjoyed semi-autonomy, but they were still recognisably Roman, rebuilt with gridded streets and well-funded public monuments. A network of Roman roads facilitated the transport of goods from one city to the next, and the wheel ruts of carriages and chariots can still be seen in the paving stones at Umm Qais and Jerash. The so-called imperial cult, which revolved around mandatory worship of the Roman emperor, helped unify the cities in the Decapolis while simultaneously ensuring that its residents didn’t forget the generosity of their Roman benefactors.

Wandering the streets of the ruined cities today, it’s easy to imagine life 2000 years ago: the centre bustling with shops and merchants, and lined with cooling water fountains and dramatic painted facades. The empty niches would have been filled with painted statues; buildings clad in marble and decorated with carved peacocks and shell motifs; and churches topped with Tuscan-style terracotta-tiled roofs.

The term Decapolis fell out of use when Emperor Trajan annexed Arabia in the 2nd century AD, although the cities continued to maintain connections with one another for a further 400 years. Their eventual demise was heralded by the conquest of the Levant in 641 by the Umayyads. Political, religious and commercial interests shifted to Damascus, marginalising the cities of the Decapolis to such an extent that they never recovered.

map Google map; Jerash’s superb colonnaded cardo maximus is straight in the way that only a Roman road can be. This is one of Jerash’s great highlights, and the walk along its entire 800m length from North Gate to the forum is well worth the effort. Built in the 1st century AD and complete with manholes to underground drainage, the street still bears the hallmarks of the city’s principal thoroughfare, with the ruts worn by thousands of chariots scored into the original flagstones.

The 500 columns that once lined the street were deliberately built at different heights to complement the facades of the buildings that stood behind them. Although most of the columns you see today were reassembled in the 1960s, they give an excellent impression of this spectacular thoroughfare.

There are many buildings of interest on either side of the cardo maximus, in various states of restoration and ruin. A highlight is the northern tetrapylon, an archway with four entrances.

map Google map; Built about AD 165 and enlarged in 235, the beautiful little North Theatre was most likely used for government meetings rather than artistic performances. Originally it had 14 rows of seats, with two vaulted passageways leading to the front of the theatre, as well as five internal arched corridors leading to the upper rows. Many of the seats are inscribed with the names of delegates who voted in the city council.

Like many of the grand monuments at Jerash, the North Theatre was destroyed by earthquakes and then partially dismantled for later Byzantine and Umayyad building projects. However, in recent years it has been magnificently restored and still maintains a capacity of about 2000 people. The theatre may not have been used for performances, but there’s still plenty of rhythm in the design details, with round niches, inverted scallop shells, and exuberant carvings of musicians and dancers at the base of the stairs.

map Google map; Two hundred metres north of the hippodrome is the imposing South Gate, which was likely constructed in AD 130 and originally served as one of four entrances along the city walls. Along the way you can see how the Roman city, then as now, spilt over both sides of Wadi Jerash, with most of the residential area lying east of the wadi. The visitor centre is on the right before the gate; hire a guide here.

One square kilometre of the city is encased by the 3m-thick, 3.5km-long boundary walls. Don’t forget to look up as you pass under the South Gate: like Hadrian’s Arch, the columns bear elaborately carved acanthus-leaf decorations and would once have supported three wooden doors. Framed by the archway is the first hint of the splendour ahead – the columns of the forum start appearing in ever greater profusion as you walk towards them.

map Google map; Built sometime between the 1st and 3rd centuries AD, this ancient sports field (244m by 50m) was once surrounded by seating for up to 15,000 spectators, 30 times the current capacity, and hosted mainly athletics competitions and chariot races. Recent excavations have unearthed the remains of stables and pottery workshops, plus indications that the site was used for polo by invading Sassanians from Persia during the early 7th century.

In recent years the hippodrome has hosted chariot races and reconstructions of Roman military manoeuvres, but falling tourist numbers since the Arab Spring have put these on ice for now.

(map Google map; ![]() %02 631 2267;

%02 631 2267; ![]() h8.30am-6pm Oct-Apr, to 5pm May-Sep)

h8.30am-6pm Oct-Apr, to 5pm May-Sep) ![]() F

F

Before you finish exploring ancient Jerash, visit this compact museum and visitor centre just above the forum. It houses a small but worthwhile selection of artefacts from the site, such as mosaics, glass, gold jewellery and coins found in a tomb near Hadrian’s Arch. Almost as good as the exhibits is the view the hill affords of Jerash, ancient and modern, spread across either side of the town’s defining wadi.

Courtyard of the FountainMonument

map Google map; This ancient fountain was once fed by a local reservoir. When it was dedicated to Dionysus, it was alleged that the god would turn its water into wine, the better to celebrate him. The paved portico of the fountain still dominates the scene.

LookoutViewpoint

Near the South Theatre, this viewpoint offers a panorama of the forum and beyond – one of the first opportunities to truly take in the size of Jerash.

map Google map; Built in AD 150, this is the monumental gateway to the Temple of Artemis. It was originally flanked by shops.

map Google map; Built in AD 162 over the remains of an earlier Roman temple, the Temple of Zeus was once approached by a magnificent stairway leading from the temenos (sacred courtyard). Today, lizards sun themselves in the cracks of pavement, oblivious to the holy sacrifices that used to take place here. Positioned on the summit of the hill, the temple towers above the city. Despite erosion and earthquakes, enough of this once-beautiful building remains to allow visitors to understand its former importance.

A path leads from the temenos to the temple, via a welcome stand of trees. You can pause here for a panorama of the forum and a small hill of pines. As you walk from the trees to the temple, notice the intricate friezes of floral and figurative motifs unearthed by French excavations. The delicacy of the design contrasts strikingly with the massive size of the building blocks that comprise the temple’s inner sanctum.

map Google map; On the western side of the cardo maximus is the elegant nymphaeum, the main ornamental fountain of Jerash, dedicated to the water nymphs. Built about AD 191, the two-storey construction was elaborately decorated, faced with marble slabs on the lower level, plastered above and topped with a half dome. Water cascaded into a large pool at the front, with the overflow pouring out through seven carved lions’ heads.

Although it’s been quite some time since water poured forth, the well-preserved structure remains one of the highlights of Jerash. Several finely sculpted Corinthian columns still frame the fountain, and at its foot is a lovely pink-granite basin, which was probably added by the Byzantines. At one point the entire structure was capped by a semi-dome in the shape of a shell, and you can still make out the elaborate capitals lining the base of the ceiling.

map Google map; The vaulted passageway under the courtyard of the Temple of Zeus is a good starting point in Jerash’s ancient city. When your eyes become accustomed to the gloom, you’ll see a superb display of columns, pediments and masonry carved with grapes, pomegranates and acanthus leaves. This is the place to brush up on the three main column styles: Doric, Ionic and Corinthian.

Take a look at the model of the Temple of Zeus, as it will help to recreate the ruins in your mind later.

map Google map; Built in about AD 115, the North Gate is an impressive full stop at the northern limit of the Jerash ruins. Commissioned by Claudius Severus, who built the road to Pella, it still makes a fine, if somewhat neglected, frame for the cardo maximus, which stretches in all its glory along the entire length of the ancient city.

If you’ve reached the North Gate, you deserve a pat on the back because very few visitors bother to walk this far.

map Google map; Marking the intersection of the cardo maximus with the south decumanus, this four-pillared structure is in good repair.

map Google map; Jerash’s Eastern Baths lie outside the gated city on the other side of the wadi in the modern town. They are lit up at night and are interestingly juxtaposed with a modern mosque, though only real archaeological enthusiasts need seek them out.

map Google map; At the eastern end of the south decumanus is a modern mosque, a reminder of how Jordan has embraced many religions over the years and continues to tolerate different forms of worship to this day.

map Google map; The unassuming walls of these buildings don’t look especially noteworthy, but they’re interesting for adding another level of historical accretion in Jerash, this time from the Islamic Umayyad period.

map Google map; Little remains of this church apart from the twin colonnades (picturesquely overgrown with wildflowers in spring) and the apse, which overlooks the Courtyard of the Fountain.

map Google map; These ruins of a former church are one of the only sites in Jerash to have a few fragments of Byzantine mosaic in situ.

Church of St John the BaptistRuins

map Google map; The circular ruins of this church contain patches of original floor mosaics.

map Google map; This archway with four entrances was built over the intersection of Jerash’s cardo maximus (the main north–south axis) and the north decumanus (an east–west street). Rebuilt in 2000, it was probably designed as a gateway to the North Theatre.

(map Google map; Macellum) On the western side of the cardo maximus is the agora, where people gathered for public meetings around the central fountain.

map Google map; On the eastern side of the cardo maximus lie the earthquake-stricken remains of the Western Baths. Dating from the 2nd century AD, the baths were once an impressive complex of hot (calidarium), warm (tepidarium) and cold (frigidarium) baths. In Roman times, public bathing fulfilled the role of a social club and attracted a wide variety of people, who gathered to exchange news and gossip as well as to enjoy music, lectures and performances.

The Western Baths represent one of the earliest examples of a dome atop a square room.

Church of St Cosmos & St DamianusChurch

map Google map; When Christianity became the state religion under Emperor Constantine in 324, all Roman monuments that were tainted by so-called pagan practices were abandoned. These structures were subsequently pilfered for building materials as Roman cities competed with one another to build glorious churches and cathedrals. A total of 15 churches lie among Jerash’s ruins, with the Church of St Cosmos & St Damianus (look for a complex with four bulbous columns and a thick outer wall) one of the best preserved.

Consecrated in 533 in memory of twin brothers – both doctors, who devoted themselves to the care of the poor and the needy, and who were martyred during the reign of Diocletian – the church boasts the best-preserved mosaics at Jerash. Stand above the retaining wall and you can clearly make out zoomorphic figures, geometric designs and medical symbols. Some of the mosaics from this church are now housed in the Museum of Popular Traditions in Amman.

Continue up the hill and just before you reach the great temple in front of you, sit on the stone sarcophagus nearby and survey the view: this is one of the best vantage points in Jerash, showing the extent of the ruins from North Gate to Hadrian’s Arch.

WORTH A TRIP

Festivals & Events

If you happen to be in Jerash in July or August it’s worth catching a show in one of its Roman theatres. Since 1981, the city has hosted an annual Festival of Culture & Arts (www.facebook.com/Festival.Jarash), which features an eclectic array of performances, including plays, poetry readings, opera and musical concerts from around the world.

Events are listed in English in the official souvenir news sheet, the Jerash Daily, printed every day of the festival, and the English-language newspapers published in Amman. Tickets cost around JD10 for events in Jerash. There are also more formal events in Amman, including at the Roman theatre downtown. Since the events change from year to year, it’s best to check online regarding the location of ticketing venues. Several bus companies, including JETT, offer special transport to Jerash, which is useful as public transport usually finishes early in the evening.

map Google map; South of the nymphaeum, an elaborate staircase rises from the cardo maximus to Jerash’s only cathedral. Little more than a modest Byzantine church, it was constructed in the second half of the 4th century on the site of earlier temples. At the height of its glory the cathedral consisted of a soaring basilica supported by three naves and it boasted a magnificent portal finely decorated with elaborate marble carvings. It’s a fascinating insight into the many periods of Jerash’s history.

map Google map; The south decumanus at Jerash once served as the Roman town’s main east–west axis. At the eastern end is the modern mosque. Take the left fork from the street’s western end up to what might be termed ‘Church Hill’, where a number of ancient churches lie in ruins. The path that runs between the South Theatre and the Temple of Artemis offers a good vantage point of the south decumanus’ double colonnade stretching to the south.

4Sleeping

Many people visit Jerash as a day trip from Amman, but an overnight stop is more rewarding. However, with only one hotel in the middle of the town, and only one other place to stay nearby, it’s important to book ahead. If you have a car, Ajloun has more accommodation and is only about a 20-minute drive away.

Olive Branch ResortHotel $$

(![]() %02 634 0555; www.olivebranch.com.jo; s/d/tr from JD37/52/63, campsites per own/hired tent JD10/12;

%02 634 0555; www.olivebranch.com.jo; s/d/tr from JD37/52/63, campsites per own/hired tent JD10/12; ![]() W

W![]() s)

s)

Around 7km from Jerash on the road to Ajloun, this hilltop hotel is situated amid olive groves and pine trees. Refurbished rooms are neat and spacious, some with balconies, others in a separate annexe below the gardens. Country fare is served in the airy restaurant.

Unstructured camping is possible in the grounds. Call ahead for bookings, as the hotel is popular for NGO and business retreats.

(map Google map; ![]() %07 7779 3907; s/d/tr/penthouses from JD25/40/50/70;

%07 7779 3907; s/d/tr/penthouses from JD25/40/50/70; ![]() W)

W)

The only hotel in Jerash boasts a spectacular location overlooking Hadrian’s Arch. Breakfast is served on the rooftop terraces, boasting a panoramic view of the Temple of Artemis to the west and Jerash’s market gardens to the east. A range of private rooms with shared bathrooms are humble but spotless; the host’s hospitality makes up for the simple amenities.

5Eating

Modern Jerash is a bustling town with several outdoor markets, as well as a smattering of kebab and falafel shops. There’s a string of no-fuss restaurants on the main street opposite the entrance to the ruins, but there’s only one place to buy refreshments inside the ruins proper.

Jordan House RestaurantBuffet$$

(map Google map; buffet JD7; ![]() h8am-9pm;

h8am-9pm; ![]() W)

W)

Serving a comprehensive buffet between 11am and 5pm, this friendly establishment at the entrance to the Jerash ruins is a good place for a Turkish coffee before starting out, and a fresh lemon and mint drink over lunch on your return.

(map Google map; ![]() %02 635 1437; buffet JD8;

%02 635 1437; buffet JD8; ![]() hnoon-8pm)

hnoon-8pm)

The only restaurant inside the Jerash ruins, this is a welcome stop for weary visitors. Located near the South Gate, it attracts large volumes of tourists, but service is quick and efficient, and it serves alcohol. The lunch buffet and barbecue is more conducive to an afternoon nap than a jaunt round ancient Jerash, but it’s tasty nonetheless.

![]() oLebanese HouseLebanese$$$

oLebanese HouseLebanese$$$

(![]() %02 635 1301; www.facebook.com/LebaneseUmKhalil; meals JD10-18;

%02 635 1301; www.facebook.com/LebaneseUmKhalil; meals JD10-18; ![]() h11am-1am;

h11am-1am; ![]() v)

v)

Nicknamed ‘Umm Khalil’, this rambling restaurant, a 10-minute walk from Jerash’s centre, has been a national treasure since it opened in 1977. On offer are plenty of sizzling and cold mezze and freshly baked bread, as well as superior salads and mouth-watering grills. If you can’t decide what to sample, try the set menu for a selection of the best dishes.

The indoor and outdoor seating gets busy with local families after 9pm.

6Drinking & Nightlife

Jerash isn’t a place for nightlife, although Lebanese House serves alcohol – a few drinks and plates of mezze make for a very pleasant evening.

8Information

Maps

Published by the Jordan Tourism Board, the free Jerash brochure includes a map, some photos and a recommended walking route. It can be found at the visitor centre in Jerash.

Anyone with a particular interest in the history of Jerash should pick up one of three decent pocket-size guides: Jerash: The Roman City, Jerash: A Unique Example of a Roman City or (the most comprehensive and readable) Jerash. All three are available at bookshops in Amman. Jerash by Iain Browning gives a more detailed historical account.

Tourist Information

Near the South Gate, the visitor centre has informative descriptions and reconstructions of many buildings in Jerash, as well as a good relief map of the ancient city. The site’s ticket office map Google map (![]() %02 635 1272) is in a modern souq with souvenir and antique shops, a post office and a semi-traditional coffeehouse. Keep your ticket, as you’ll have to show it at the South Gate.

%02 635 1272) is in a modern souq with souvenir and antique shops, a post office and a semi-traditional coffeehouse. Keep your ticket, as you’ll have to show it at the South Gate.

Toilets are available at the site entrance (inside the souvenir souq), at Jerash Rest House and at the visitor centre.

It’s possible to leave limited luggage at Jerash Rest House, for no charge, while you visit the site.

8Getting There & Away

Jerash is located approximately 50km north of Amman, and the roads are well signposted from the capital, especially from 8th Circle. If you’re driving, note that this route can get extremely congested during the morning and afternoon rush hours.

From the North Bus Station (Tabarbour) in Amman, public buses and minibuses (800 fils, 1¼ hours) leave regularly for Jerash, though they can take an hour to fill up. Leave early for a quick getaway, especially if you’re planning a day trip.

Jerash’s bus and service-taxi station is a 15-minute walk southwest of the ruins, at the second set of traffic lights, behind the big white building. You can pick up a minibus to the station from outside the visitor centre for a few fils. From here, there are also plenty of minibuses travelling regularly to Irbid (JD1, 45 minutes) and Ajloun (500 fils, 30 minutes) until around 4pm. You can normally flag down the bus to Amman from the main junction in front of the site to save the trek to the bus station.

Transport drops off significantly after 5pm. Service taxis sometimes leave up to 8pm (later during the Jerash Festival) from the bus station, but this is not guaranteed.

A private taxi between Amman and Jerash should cost around JD20 each way. From Jerash, a taxi to Irbid costs around JD15.

Dibeen Forest Reserve محمية غابات دبين

Established in 2004, this nature reserve (www.rscn.org.jo/content/dibeen-forest-reserve) ![]() F consists of an 8-sq-km area of Aleppo pine and oak forest. Managed by the Royal Society for the Conservation of Nature (RSCN), Dibeen is representative of the wild forests that once covered much of the country’s northern frontiers but which now account for only 1% of Jordan’s land area. Despite its small size, Dibeen is recognised as a national biodiversity hot spot and protects 17 endangered animals (including the Persian squirrel) and several rare orchids.

F consists of an 8-sq-km area of Aleppo pine and oak forest. Managed by the Royal Society for the Conservation of Nature (RSCN), Dibeen is representative of the wild forests that once covered much of the country’s northern frontiers but which now account for only 1% of Jordan’s land area. Despite its small size, Dibeen is recognised as a national biodiversity hot spot and protects 17 endangered animals (including the Persian squirrel) and several rare orchids.

There are some short marked (but unmapped) hiking trails through the park. In March and April carpets of red-crown anemones fill the meadows beneath the pine-forested and sometimes snowcapped hills. Most trails are either small vehicle tracks or stony paths, some of which continue beyond the park’s boundaries. The area is very popular with local picnickers on Fridays, and litter is a problem. The park is only usefully accessed by car. Follow the signs from Jerash and expect to get lost! Keep heading for the obvious hillside woodland as you pass through nearby hamlets and you’ll eventually stumble on the entrance.

Ajloun عجلون

![]() %02 / Pop 9990 / Elev 744m

%02 / Pop 9990 / Elev 744m

It may look a bit rough around the edges, but Ajloun (or Ajlun) is founded on an ancient market town and boasts a 600-year-old mosque with a fine stone-dressed minaret. Most visitors, however, don’t come to exper-ience this chaotic little hub and its limited attractions: they come for the impressive castle perched atop a nearby hill, where it has commanded the high ground for nearly 1000 years.

With the biblical site of Mar Elias and one of Jordan’s best nature reserves in the vicinity, Ajloun makes a good base for a couple of days of exploration. It’s also reasonably close to Jerash (30 minutes by minibus, 20 minutes by car), offering alternative accommodation and making a rewarding weekend circuit from Amman.

1Sights

![]() oAjloun CastleCastle

oAjloun CastleCastle

(Qala’at Ar Rabad; JD3, with Jordan Pass free)

This historic castle was built atop Mt ‘Auf (1250m) between 1184 and 1188 by one of Saladin’s generals, ‘Izz ad Din Usama bin Munqidh (who was also Saladin’s nephew). The castle commands views of the Jordan Valley and three wadis leading into it, making it an important strategic link in the defensive chain against the Crusaders and a counterpoint to the Crusader Belvoir Fort on the Sea of Galilee in present-day Israel and the Palestinian Territories.

The castle was enlarged in 1214 with the addition of a new gate in the southeastern corner, and once boasted seven towers as well as a 15m-deep dry moat. With its hilltop position, Qala’at Ar Rabad was one in a chain of beacons and pigeon posts that enabled messages to be transmitted from Damascus to Cairo in a single day. The rearing of pigeons is still a popular pastime in the area.

After the Crusader threat subsided, the castle was largely destroyed by Mongol invaders in 1260, only to be almost immediately rebuilt by the Mamluks. In the 17th century an Ottoman garrison was stationed here, after which it was used by local villagers. Earthquakes in 1837 and 1927 badly damaged the castle, though slow and steady restoration is continuing.

Note that there is a useful explanation in English just inside the main gate, and a small museum containing pots, snatches of mosaics and some intriguing medieval hand grenades. Apart from this, nothing else in the castle is signposted, although not much explanation is needed to bring the place to life, especially given that the views from these lofty heights are nothing short of spectacular.

The castle is a tough 3km uphill walk from the town centre, but minibuses very occasionally go to the top (about 100 fils). Alternatively, take a taxi from Ajloun (JD1 to JD2 each way). The visitor centre and ticket office is about 500m downhill from the castle entrance; there’s a small scale model of the castle on display here and, perhaps more usefully, clean toilets.

The Jordan Trail: Ajloun to Fuheis

Distance 60km

Duration Four days

Ajloun Castle provides a dramatic starting point for this section of the Jordan Trail. The route begins amid pine forest and olive groves as you hike down along the cliffs of Wadi Mahmoud to the village of Khirbet Al Souq, The following day leads you to the spectacular King Talal Dam and its reservoir. Country tracks take you towards Rmeimeen, a typical village in this area, with its mosque and church side by side. You’re briefly shaken from rural life as you rise up from the valley to cross the main highway at Al Ahliyya, but it’s a reminder that you’re near your reward for finishing this section of the trail: a cold beer at Jordan’s only microbrewery, Carakale, in Fuheis.

This section of the trail is particularly good for wild camping. Visit www.jordantrail.org for route maps, GPS waypoints and detailed breakdowns of daily hikes.

Mar EliasArchaeological Site

(![]() h8am-7pm Apr-Oct, to 4pm Nov-Mar)

h8am-7pm Apr-Oct, to 4pm Nov-Mar) ![]() F

F

This little-visited archaeological site, believed to be the birthplace of the prophet Elijah, gives you just the excuse you need to explore the countryside around Ajloun. To be honest, it’s not a spectacular site by any stretch of the imagination, though it’s worth visiting for its religious and historical significance.

4Sleeping

There are two hotels on the road up to the castle, either of which is a good option if you want to enjoy the sunset from the castle ramparts.

Ajloun HotelHotel$

(![]() %02 642 0524; s/d JD27/35;

%02 642 0524; s/d JD27/35; ![]() W

W![]() s)

s)

This is a handy option for an early morning visit to the castle, as it’s located just 1km down the road. There’s a comfortable lounge area in the foyer, and decent basic rooms. Choose a top-floor room for grand views of the countryside.

Mountain Castle HotelHotel$

(![]() %07 9565 6726, 02 642 0202; s/d from JD28/38;

%07 9565 6726, 02 642 0202; s/d from JD28/38; ![]() W)

W)

This busy little hotel boasts a gorgeous garden terrace of flowering jasmine, grapevines and roses – enjoying your meals here will be a highlight of your stay. The decor is a tad tired and the furnishings on the minimal side, but there are expansive views from many of the rooms.

5Eating

There are a few places for a snack and a drink at the entrance to Ajloun Castle. You can pick up supplies in Ajloun’s grocery stores, supplement your rations with freshly picked fruit from the many roadside fruit stands, and head into the surrounding hills for a picnic.

Abu Alezz RestaurantJordanian$

(Abdallah bin Hussein St; meals JD2-4; ![]() h10am-9pm)

h10am-9pm)

Near the main roundabout, this restaurant has cheap and tasty standard Jordanian fare, including grilled chicken, hummus and shawarma (meat sliced off a spit and stuffed in a pocket of pita-type bread with chopped tomatoes and garnish).

BarhoumJordanian$

(Abdallah bin Hussein St; meals JD2-6; ![]() h10am-9pm)

h10am-9pm)

In central Ajloun, and handy for grilled meats, hummus, salads and the like.

8Getting There & Away

Ajloun is approximately 75km northwest of Amman and 30km northwest of Jerash. The castle can be clearly seen from most places in the area – if you’re driving or walking, take the signposted road (Al Qala’a St) heading west at the main roundabout in the centre of Ajloun. The narrow streets of the town centre can be horribly congested at times.

From the centre of town, minibuses travel regularly to Jerash (800 fils, 30 minutes), along a scenic road and Irbid (JD1, 45 minutes). From Amman (JD1, two hours), minibuses leave half-hourly from the North Bus Station.

Ajloun Forest Reserve محمية غابات عجلون

Located in the Ajloun Highlands, this small (just 13 sq km) but vitally important nature reserve (![]() %02 647 5673; www.wildjordan.com; per day JD2.500) was established by the RSCN in 1988 to protect oak, carob, pistachio and strawberry-tree forests. The reserve also acts as a sanctuary for the endangered roe deer, as well as wild boar, stone martens, polecats, jackals and even grey wolves. The landscape of rolling hills and mixed forest is lovely, especially if you’ve been spending a few too many hours in Jordan’s deserts or congested capital.

%02 647 5673; www.wildjordan.com; per day JD2.500) was established by the RSCN in 1988 to protect oak, carob, pistachio and strawberry-tree forests. The reserve also acts as a sanctuary for the endangered roe deer, as well as wild boar, stone martens, polecats, jackals and even grey wolves. The landscape of rolling hills and mixed forest is lovely, especially if you’ve been spending a few too many hours in Jordan’s deserts or congested capital.

The RSCN has developed a good network of hiking trails, with a variety of paths suited to hikers of all fitness levels. At the edge of the reserve, the villages of Orjan, Rasoun and Baoun have linked together in a community-tourism initiative to promote hiking in the area with their own Al Ayoun Trail; they also offer homestays with local families.

WORTH A TRIP

Community Tourism on the Al Ayoun Trail

The villages around Ajloun have been at the forefront of developing community-tourism projects in Jordan. At the heart of this is the 12km Al Ayoun Trail, linking the three villages of Orjan, Rasoun and Baoun to the ruins at Mar Elias, and managed by the cooperative Al Ayoun Society. The scenery is delightful, but the real point is to enable visitors to hike through the villages and interact with the community, stopping for tea, tasting fresh bread and produce, and meeting farmers with their animals. This makes taking a local guide an essential part of the experience; you can expect to pay around JD50, knowing that 100% of the money stays in the community. The Al Ayoun Society has also helped several families set up their houses as homestays. There’s no better or more enjoyable way to learn about the local area. Talk to lead organisers Eisa Dweekat and Mohammed Sawlmeh to make arrangements for both walking and homestays.

For extended hikes in the area, including in Ajloun Forest Reserve, to Ajloun Castle and as far away as Pella, pick up a copy of Di Taylor and Tony Howard’s excellent Walks, Treks, Climbs & Caves in Al Ayoun, Jordan. It offers 20 routes lasting from two hours to two days, with detailed maps and GPS waypoints, as well as information on rock climbing and caving in the area.

1Sights

The Royal Society for the Conservation of Nature (RSCN) supports a number of community projects in and near the reserve to help develop new sources of income for the local population. These small-scale, high-value projects include three workshops that produce olive-oil soap, screen-printed items and traditional Jordanian cuisine, all of which can be purchased on-site or in the reserve’s Nature Shop. The three workshops are free to visit. Pick up a map from the visitor centre before you set out – it’ll call ahead to make sure they open up for you.

House of CalligraphyWorkshop

(Orjan; ![]() hby appointment via Wild Jordan)

hby appointment via Wild Jordan)

You don’t have to be a linguistic scholar to enjoy the dynamic rhythms of Arabic script. Reinforcing Islamic heritage, the women in this workshop aim to educate visitors about Arab culture, and there’s even an opportunity to try your hand at calligraphy as you use a reed to write your name in Arabic.

Biscuit HouseWorkshop

(Orjan; ![]() hby appointment via Wild Jordan)

hby appointment via Wild Jordan)

Delicious Jordanian delicacies are prepared for sale in RSCN Nature Shops in this cottage-industry kitchen. With an on-site cafe selling locally produced herbal teas, olive-oil crisps, and molasses and tahini sandwich cookies, it’s tempting to stay until morning.

Soap HouseWorkshop

(Orjan; ![]() hby appointment via Wild Jordan)

hby appointment via Wild Jordan)

Ever wondered what pomegranate soap smells like? Local women demonstrate the art of making all kinds of health-promoting soaps using natural local ingredients and comprising 90% pure olive oil. Pomegranate is one of a dozen exotic fragrances.

2Activities

Ajloun is great walking country. In addition to a spur of the Jordan Trail, there are lots of local hikes leading from Ajloun Forest Reserve. It’s important to arrange return transport at the visitor centre before you leave on any hike except the Roe Deer and Rockrose Trails. Trails are maintained by the RSCN and each has a specific hiking fee. For most trails, a guide (included in the fee, along with the reserve entrance fee) is compulsory.

An excellent local-tourism cooperative, Al Ayoun Society (![]() %07 9682 9111, 07 7973 4776; www.facebook.com/alayounsociety), based in Orjan village can arrange guides for the Al Ayoun Trail as well as homestays in Orjan and Rasoun. Taking its guides on the trail is one of the best ways to discover the Jordanian countryside and village life.

%07 9682 9111, 07 7973 4776; www.facebook.com/alayounsociety), based in Orjan village can arrange guides for the Al Ayoun Trail as well as homestays in Orjan and Rasoun. Taking its guides on the trail is one of the best ways to discover the Jordanian countryside and village life.

Roe Deer Trail

If you’re just stopping by for the day, the 2km, self-guided Roe Deer Trail is included in the reserve entrance fee. It starts from the accommodation area, looping over a nearby hill – past a 1600-year-old stone wine press and lots of wildflowers (in April) – and returning via a roe-deer enclosure.

Soap House Trail

This guided 7km trail (three hours, JD16.500) combines a visit to the reserve’s oldest strawberry tree with a panoramic vista at Eagle’s Viewpoint. Descending from the 1100m lookout, the trail leads through evergreen woodland to the Soap House, where enterprising women make natural olive-oil soap.

Orjan Village Trail

A guide is needed for this rural 12km trail (six hours, JD26 including meal) that weaves alongside a brook, passing poplar trees and orchards. The olive trees at the end of the hike date back to Roman times. The trail is open April to October only.

Rockrose Trail

This scenic 8km trail (four hours, JD16.500) involves some steep scrambling and requires a guide. The route passes through heavily wooded valleys, near rocky ridges and alongside olive groves and offers sweeping views of the West Bank. The trail is open April to October only.

Prophet’s Trail

Terminating at the archaeological site of Mar Elias, where it’s said the prophet Elijah was born, this 8.5km guided route (four hours, JD22 including packed lunch) winds through fig and pear orchards. At Wadi Shiteau the trail plunges into a dense forest of oaks and strawberry trees.

Ajloun Castle Trail

With prior arrangement, it’s possible to continue hiking from Mar Elias for another 9.5km through Wadi Al Jubb to Ajloun Castle – a tough extra four hours over rough and steep terrain. The trail is ‘donkey assisted’, which helps considerably on the difficult final ascent towards the castle

4Sleeping & Eating

There are two choices: stay in the Ajloun reserve itself, or at a homestay in one of the nearby villages. The Al Ayoun Society can arrange meals with families in the local homestays if you contact it in advance.

![]() oAl Ayoun HomestaysHomestay$$

oAl Ayoun HomestaysHomestay$$

(![]() %07 9682 9111, 07 7973 4776; www.facebook.com/alayounsociety; homestays around JD20-40)

%07 9682 9111, 07 7973 4776; www.facebook.com/alayounsociety; homestays around JD20-40)

The Al Ayoun Society is a local community-tourism initiative that can arrange home-stays in the lovely rural village of Orjan near Ajloun, where a stream, olive groves and ancient poplars make a pleasant change from the dusty hills of Ajloun. Several families offer their houses as B&Bs, where you’re guaranteed a warm welcome and delicious home-cooked food.

Ajloun Reserve CabinsCabin$$$

(![]() %02 647 5673; s/d/tr with shared bathroom from JD82/93/105, deluxe cabins s/d/tr JD105/116/128)

%02 647 5673; s/d/tr with shared bathroom from JD82/93/105, deluxe cabins s/d/tr JD105/116/128)

These rustic cabins with terraces overlooking a patch of forest make for a delightful retreat. Regular cabins share environmentally sound composting toilets and solar-heated showers; the stylish deluxe cabins are en suite. Lunch and dinner are available by reservation in the tented rooftop restaurant, though you can always cook for yourself on the barbecues. Bring plenty of mosquito repellent in summer.

Rooftop RestaurantJordanian$$$

(![]() %02 647 5673; buffet JD14)

%02 647 5673; buffet JD14)

Meals are available in this tented rooftop restaurant at Ajloun reserve if you give them some notice. From the rooftop, check out the great views of snowcapped Jabal Ash Sheikh (Mt Hermon; 2814m) on the Syria–Lebanon border.

8Information

At the entrance to the reserve is a modest visitor centre (www.wildjordan.com; ![]() hdawn-dusk) with a helpful reception where you’ll find information and maps on the reserve and its flora and fauna. There’s also a Nature Shop selling locally produced handicrafts.

hdawn-dusk) with a helpful reception where you’ll find information and maps on the reserve and its flora and fauna. There’s also a Nature Shop selling locally produced handicrafts.

You should book accommodation and meals in advance with the RSCN through its Wild Jordan Center in Amman. If you’re planning to take a guided hike, you must book 48 hours ahead. Guided hikes require a minimum of four people and start at JD9 per person, depending on the choice of trail.

8Getting There & Away

You can reach the reserve by hiring a taxi from Ajloun (around JD6, 9km); ask the visitor centre to book one for your departure. If you’re driving, the reserve is well signposted. Take the road from Ajloun towards Irbid and make a left turn by a petrol station 5km from Ajloun towards the village of Ishfateena. About 300m from the junction, take a right and follow the signs to the reserve, which is next to the village of Umm Al Yanabi.

Irbid & Around

Jordan’s far-flung northern hills were once popular with those heading overland to Syria, but these days see relatively few travellers. This is a shame as the region’s rolling hills and verdant valleys are home to characterful rural villages, country lanes overrun by goats, and ubiquitous olive groves among whose ancient trunks lie the scattered remains of forgotten eras.

And then, of course, there is Irbid. This thriving university town is generally overlooked by visitors, despite some national treasures; in this densely populated part of the country, Irbid is a key place in which to feel the pulse of modern Jordan.

All minibuses, in whatever village you find them, appear to make a beeline for Irbid, from where connections can be made to almost anywhere in the country. With a car, it’s possible to visit the remote battleground of Yarmouk or the ruins of the Decapolis city of Umm Qais as a day trip from Irbid.

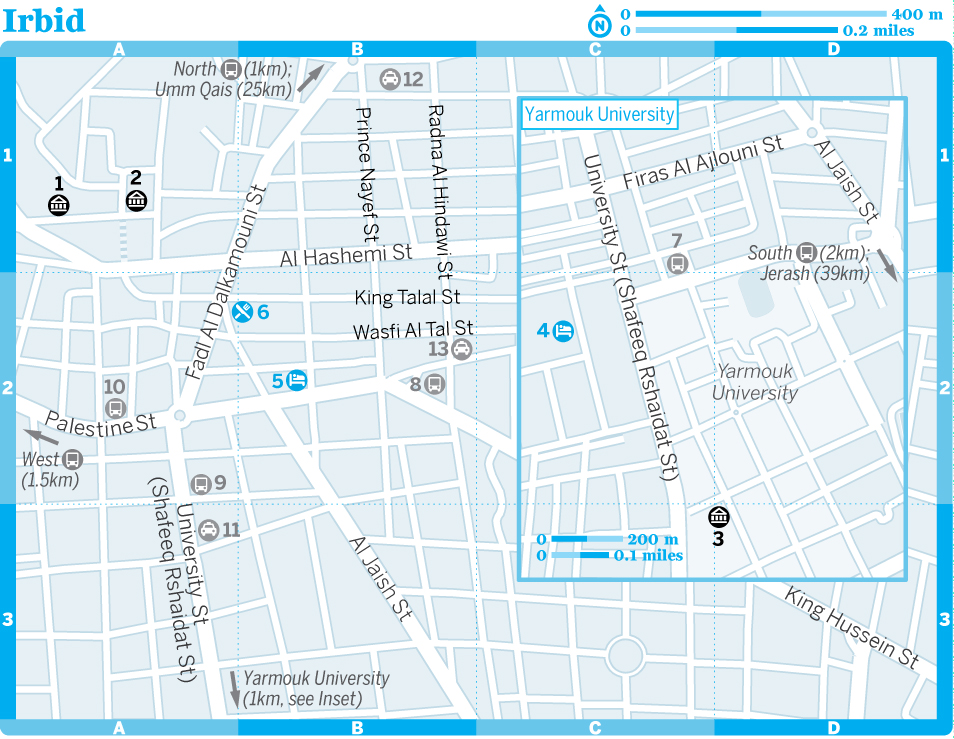

Irbid إربد

![]() %02 / Pop 502,700 / Elev 582m

%02 / Pop 502,700 / Elev 582m

Jordan’s second-largest city is something of a glorified university town. Home to Yarmouk University, which is regarded as one of the most elite centres of learning in the Middle East, Irbid is in many ways more lively and progressive than staid Amman. The campus, which is located just south of the city centre, is home to shady pedestrian streets lined with outdoor restaurants and cafes. Since the start of the crisis in Syria, Irbid has taken in large numbers of refugees, who live in the city itself or in the extensive camp on the outskirts.

Historians and archaeologists have identified Irbid as the Decapolis city of Arbela. The area likely predates the Romans, with significant grave sites suggesting settlement since the Bronze Age. Aside from the tell lying at the centre of town, however, there is little evidence today of such antiquity.

Irbid

8Transport

1Sights

(map Google map; ![]() %02 724 5613; Al Baladia St; JD2, with Jordan Pass free;

%02 724 5613; Al Baladia St; JD2, with Jordan Pass free; ![]() h8am-6pm)

h8am-6pm)

Located in a stunning old villa of basaltic rock that’s located just behind the town hall, this museum is an interesting diversion. Built in 1886 by the Ottomans, the building is typical of the caravanserai established along the Syrian pilgrimage route, with rooms arranged around a paved internal courtyard. It was used as a prison until 1994 and now houses a delightful collection of local artefacts illustrating Irbid’s long history.

Museum of Archaeology & AnthropologyMuseum

(map Google map; ![]() %02 721 1111;

%02 721 1111; ![]() h10am-1.45pm & 3-4.30pm Sun-Thu)

h10am-1.45pm & 3-4.30pm Sun-Thu) ![]() F

F

This museum features exhibits from all eras of Jordanian history. The collection opens with 9000-year-old Neolithic statuettes found near Amman, covers the Bronze and Iron Ages, continues through the Mamluk and Ottoman occupations, and closes with modern displays on rural Bedouin life. One of the highlights is a reconstruction of a traditional Arab pharmacy and smithy. The Numismatic Hall has some fascinating displays on the history of money over 2600 years. All displays are labelled in English.

(map Google map; ![]() h9am-5pm Sun-Thu)

h9am-5pm Sun-Thu) ![]() F

F

Set up to host occasional cultural events, Beit Arar is located off Al Hashemi St in a superb old Damascene-style house. The rooms are set around a courtyard paved with volcanic black stones, and there are photo displays on Arar, one of Jordan’s finest poets, as well as some of his manuscripts.

4Sleeping

There’s little pressing reason to stay in Irbid, which is fortunate, as the hotel standard is not high.

(map Google map; ![]() %02 724 5955; omayahhotel@yahoo.com; King Hussein St; s/d JD24/32)

%02 724 5955; omayahhotel@yahoo.com; King Hussein St; s/d JD24/32)

Decent value for money, this budget hotel boasts satellite TV and fridges, as well as large picture windows overlooking the heart of the city. The friendly proprietor is kind and helpful, and solo women will feel comfortable here. Rooms towards the back of the property and away from the main road are a bit quieter.

(map Google map; ![]() %02 727 5515; s/d/tr from JD35/40/55;

%02 727 5515; s/d/tr from JD35/40/55; ![]() i

i![]() s)

s)

Located near the campus of Yarmouk University, off University St. Rooms are spacious but tired. The hotel has a popular cafe and restaurant.

5Eating

University St has the greatest congregation of eating spots, all patronised by students. The fare’s pretty standard, but the real attraction is the evening vibe: after 9pm the streets swell with crowds looking for a good night out and seeming to find it on the promenade between roundabouts.

The street market sells all manner of fresh fruit from northern orchards.

Clock Tower RestaurantJordanian$

(map Google map; Al Jaish St; meals JD3-5; ![]() h8.30am-11.30pm)

h8.30am-11.30pm)

The name of this popular local is written in Arabic, but as it’s right next to the clock tower and has a huge spit of shawarma roasting in the window, it’s hard to miss. There’s a family seating area upstairs for a bit of peace and quiet, and the Jordanian staple dishes are cheap, cheerful and delicious.

(map Google map; pizza JD2.500; ![]() h10am-midnight)

h10am-midnight)

Downstairs from the Al Joude Hotel, this is one of the most popular gathering places for Irbid’s cool set. Styled along the lines of a Western-style coffee shop, the News Café is warm and inviting, offering coffee, milkshakes, pizza and other snacks. It’s off University St.

(map Google map; King Hussein St)

Self-caterers and would-be picnickers should head to this supermarket near the Omayah Hotel; it has a good selection of local produce, including the region’s justifiably famous olives.

Al Joude Garden RestaurantJordanian$$

(map Google map; mixed-grill meals JD5-10)

Students, visiting parents and local families crowd into the courtyard outside Al Joude Hotel to sip fresh fruit juices and smoke a strawberry shisha (water pipe). The waiters are kept in a constant state of rush in this teeming venue as they are summoned for hot embers and top-ups of Turkish coffee – expect long waits for food orders. It’s off University St.

6Drinking & Nightlife

Irbid has its share of grungy bars, where the testosterone is on tap as much as the beer. Stick to the student-friendly coffee shops if you want a more genial night out.

8Getting There & Away

Approximately 85km north of Amman, Irbid is home to three main minibus/taxi stations.

From the North Bus Station (Tabarbour), there are minibuses to Umm Qais (45 minutes), Mukheiba (for Al Himma; one hour) and Quwayliba (for the ruins of Abila; 25 minutes); fares are between 400 fils and JD1.

From the large South Bus Station map Google map (new Amman bus station; Wahadat), air-conditioned Hijazi buses (JD2, 90 minutes) leave every 15 to 20 minutes between 6am and 7pm for Amman’s North Bus Station. There are also less comfortable buses and minibuses from Amman’s North Bus Station (less than JD1, about two hours) and plenty of service taxis (JD1). Minibuses also leave the South Bus Station for Ajloun (45 minutes) and Jerash (45 minutes); fares are around 800 fils.

From the West Bus Station map Google map (Mujamma Al Gharb Al Jadid), about 1.5km west of the centre, minibuses go to Al Mashari’a (45 minutes) for the ruins at Pella, Sheikh Hussein Bridge (for Israel and the Palestinian Territories; 45 minutes) and Shuneh Ash Shamaliyyeh (North Shuna; one hour); fares are between 800 fils and JD1.200.

8Getting Around

Getting between Irbid’s various bus stations is easy, with service taxis (200 fils) and minibuses (100 fils) shuttling between them and the centre. Service taxis and minibuses to the South Bus Station can be picked up on Radna Al Hindawi St; for service taxis to the North Bus Station, head to Prince Nayef St. For the West Bus Station, take a bus from Palestine St, just west of the roundabout.

The standard taxi fare from the centre (Al Bilad) to the university (Al Jammiya) is 500 fils; few taxis use meters in Irbid.

A minibus from University St to the university gate costs 200 fils. There are also service taxis, or it’s a 25-minute walk. There’s a stop on Abdel Qadir Al Tall St for minibuses and service taxis back downtown.

Irbid’s traffic is notoriously bad. If you have a car, be aware that the congestion, one-way roads and lack of parking can make driving a stressful experience.

Abila (Quwayliba) (ابيلا (قويلبة

Lying 10km north of Irbid, between the hills of Tell Abila and Tell Umm Al Amad, are the remains of the Decapolis city of Abila (![]() hdaylight hours)

hdaylight hours) ![]() F. Largely unexcavated, the site isn’t set up for visitors, but you don’t need a guide to find the Roman-Byzantine theatre or the scattered remains of columns from the markets, temples and baths. Buses leave from Irbid’s North Bus Station for Quwayliba (less than JD1, 25 minutes), near the site; ask the driver to drop you at the ruins.

F. Largely unexcavated, the site isn’t set up for visitors, but you don’t need a guide to find the Roman-Byzantine theatre or the scattered remains of columns from the markets, temples and baths. Buses leave from Irbid’s North Bus Station for Quwayliba (less than JD1, 25 minutes), near the site; ask the driver to drop you at the ruins.

Yarmouk Battleground

If you have a car and are intrigued to know why all roads out of Irbid seem to lead to Yarmouk battleground, follow the signs northeast towards the village of Saham Al Kfarat. The site is of great significance to Muslim Arabs, as this was where, on 12 August 636, an army of 40,000 Arabs confronted 125,000 Byzantine fighters and emerged victorious.

A lot of blood was spilled that day, with 4000 Arabs and 80,000 of their adversaries killed, and the battleground remains something of a pilgrimage site even now. The signposted road from Irbid leads not to the battleground itself but to a spectacular viewpoint, high above the Yarmouk River, which marks the border with Syria. The battle took place in the valley below, but from this vantage point it’s easy to see how the disciplined, motivated, mobile and homogeneous Arabs, united by faith and good leadership, were able to overcome the mercenary Byzantine groups. The latter, who had no belief in the fight, lacked strategy and were ill-disciplined, and they were particularly disadvantaged by their heavy armour – as can easily be imagined on a hot August day as you look down at the steep, sun-parched hillsides opposite the viewpoint. The viewpoint, which has an interpretative plaque and a monument but no facilities, is not accessible by public transport. By car, it’s a 30-minute drive from Irbid; don’t give up on the signs – they’re just widely spaced. A shortcut to Umm Qais is signposted halfway between the viewpoint and Irbid.

The Jordan Valley

The Jordan Valley and the hills that surround it are well worth exploring for the scenery, archaeological sites in Pella and Umm Qais, and community-tourism projects in the latter, overlooking the Sea of Galilee in Israel and the Palestinian Territories. The valley has supported human settlement since antiquity, sustained by the rich soil that to this day makes farming a logical pursuit. Visitors will be struck by the contrast between the olive-growing hillsides and the subtropical Jordan Valley; they will also probably note the heavily policed border with Israel and the Palestinian Territories, which runs along the length of the river. The valley has been the site of conflict for centuries and it’s still a sensitive area, as disputes about territory give way to concerns over water.

The Jordan Valley is easily accessible from Amman, so many people visit as a day trip. However, Umm Qais has one of the most charming guesthouses in the country, making a longer visit to the area more feasible. Umm Qais has the best eating options in the area. You can also stop at roadside stalls and treat yourself to some fresh local produce straight from the farm.

8Getting There & Away

There’s plenty of public transport plying the valley from village to village, with Irbid as the main hub. With a car, however, it’s considerably easier to make side trips from the valley floor (which is well below sea level) to places of interest above sea level, such as the ruins at Pella or the bustling town of Salt. It takes about 1½ hours to drive the full length of the valley.

The valley has two of Jordan’s three border posts with Israel and the Palestinian Territories: at the King Hussein and Sheikh Hussein Bridges. Even if you’re not crossing, don’t forget your passport to show at the numerous police checkpoints.

The Jordan Valley

Forming part of the Great Rift Valley that runs from Africa to Syria, the fertile valley of the Jordan River was of considerable significance in biblical times, and is now regarded as the food bowl of Jordan.

The hot, dry summers and short, mild winters make for ideal growing conditions, and (subject to water restrictions) two or three crops are grown every year. The main ones are tomatoes, cucumbers, melons and citrus fruits, many of which are cultivated under plastic.

The Jordan River rises from several sources, mainly the Anti-Lebanon Range in Syria, and flows south into the Sea of Galilee, 212m below sea level, before draining into the Dead Sea. The actual length of the river is 360km, but as the crow flies the distance between its source and the Dead Sea is only 200km.

It was in the Jordan Valley, some 10,000 years ago, that people first started to plant crops and abandon their nomadic lifestyle for permanent settlements. Villages were built and primitive irrigation schemes were undertaken; by 3000 BC produce from the valley was being exported to neighbouring regions, much as it is today.

The Jordan River is revered by Christians, mainly because Jesus is said to have been baptised in its waters by John the Baptist at the site of Bethany-Beyond-the-Jordan. Centuries earlier, Joshua is believed to have led the Israelite armies across the Jordan River near Tell Nimrin (Beth Nimrah in the Bible) after the death of Moses, marking the symbolic transition from the wilderness to the land of milk and honey.

Since 1948 the Jordan River has marked the boundary between Jordan and Israel and the Palestinian Territories, from the Sea of Galilee to the Yarmouk River.

During the 1967 war with Israel, Jordan lost the West Bank, and the population on the Jordanian east bank of the valley dwindled from 60,000 before the war to 5000 by 1971. During the 1970s, new roads and fully serviced villages were built and the population has now soared to more than 100,000.

Mukheiba المخيبة

![]() %02 / Pop 1500 / Elev -130m

%02 / Pop 1500 / Elev -130m

If you’re staying in Umm Qais or visiting the Yarmouk Battleground viewpoint, you may be interested to descend to the hot springs of Al Himma in the village of Mukheiba. At the confluence of the Yarmouk and Jordan Rivers, you can gain a good idea of the battle site from the ground, although access to the site proper is currently restricted.

Several of the hikes and bike tours offered by Baraka Destinations in Umm Qais visit Mukheiba and include access to the hot springs.

8Getting There & Away

Mukheiba marks the northernmost reach of Jordan’s portion of the Jordan Valley, 10km north of Umm Qais. The town can be reached via a scenic road (with checkpoints – carry your passport) giving views of the Golan Heights and the Sea of Galilee across the border in Israel and the Palestinian Territories. Public transport is not reliable here, so you’ll need your own vehicle.

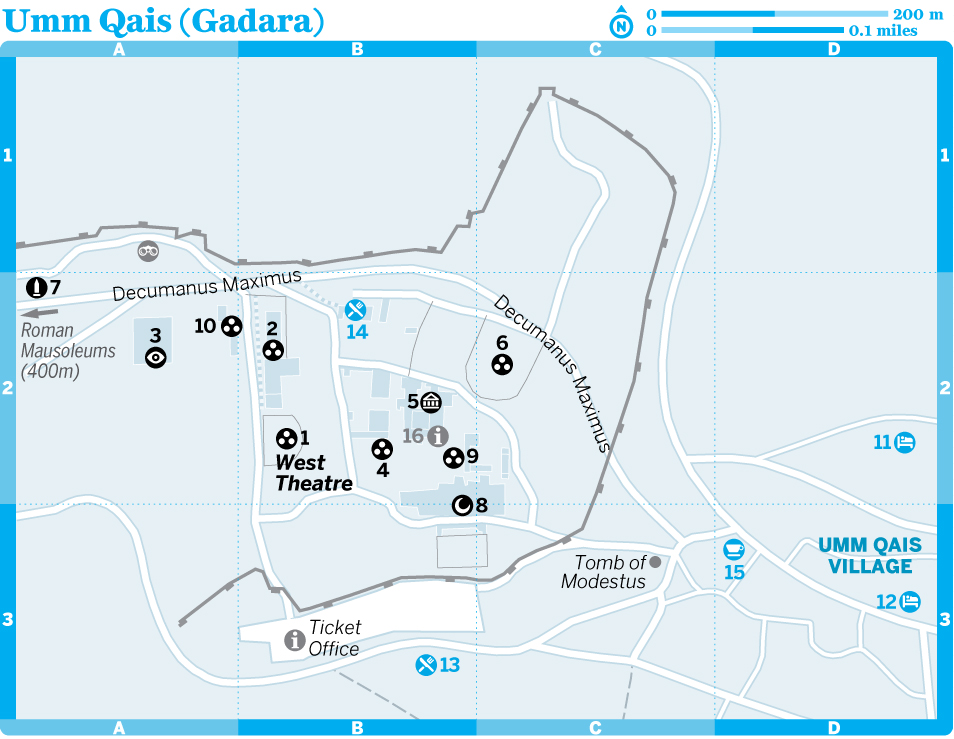

Umm Qais (Gadara) أم قيس

![]() %02 / Pop 6100 / Elev 310m

%02 / Pop 6100 / Elev 310m

In the northwestern corner of Jordan, in the hills above the Jordan Valley, are the ruins of the Decapolis city of Gadara map (JD3, with Jordan Pass free), now called Umm Qais. The site is striking because of its juxtaposition of Roman ruins with an abandoned Ottoman-era village, as well as its tremendous vantage point, with views of three countries (Jordan, Syria, and Israel and the Palestinian Territories), encompassing the Golan Heights, Mt Hermon and the Sea of Galilee.

According to the Bible, it was here that Jesus performed the miracle of the Gadarene swine: casting the demons out of two men into a herd of pigs.

Today Umm Qais is at the forefront of community-tourism development in Jordan, and it’s worth staying a night or two to enjoy an increasing array of options, from hiking and biking to beekeeping, foraging and cooking classes.

History

The ancient town of Gadara was ruled by a series of powerful nations, including the Ptolemies, the Seleucids, the Jews and, from 63 BC, the Romans, who transformed the town into one of the great cities of the Decapolis.

Herod the Great was given Gadara following a naval victory and he ruled over it until his death in 4 BC – much to the disgruntlement of locals, who tried everything to put him out of favour with Rome. On his death the city reverted to semi-autonomy as part of the Roman province of Syria, and it flourished in various guises until the 7th century when, in common with other cities of the Decapolis, it lost its trading connections and became little more than a backwater.

The town was partially rebuilt during the Ottoman Empire and many structures from this period, built in the typical black basaltic rock of the region, remain well preserved alongside the earlier Roman ruins. The Ottomans used the town as a tax-collection centre. They called it M’keis, but a 1960s government census mistook the local accent of residents and transcribed the town’s name as Umm Qais, which has stuck with official sanction ever since.

In 1806 Gadara was ‘discovered’ by Western explorers, but excavation did not commence in earnest until the early 1980s. Considerable restoration of the Roman ruins has taken place, but this involved the removal of families who had lived in the ruins for generations.

1Sights

map Google map; Entering Umm Qais from the south, the first structure of interest is the well-restored and brooding West Theatre. Constructed from black basalt, it once seated about 3000 people. This is a place to sing or declaim a soliloquy – the acoustics are fantastic.

Lookout PointViewpoint

This viewpoint offers tremendous vistas over Israel and the Palestinian Territories across the Sea of Galilee and the Golan Heights.

Decumanus MaximusRoman Site

Still paved to this day, the main road through the site once linked Gadara with other nearby ancient cities such as Abila and Pella. In its heyday, the road extended as far as the Mediterranean coast.

(map Google map; ![]() %02 750 0072;

%02 750 0072; ![]() h8am-6pm Sat-Thu, to 4pm Fri)

h8am-6pm Sat-Thu, to 4pm Fri) ![]() F

F

Housed in Beit Russan, the former residence of an Ottoman governor, this modest museum is set around an elegant and tranquil courtyard of fig trees. The main mosaic on display (dating from the 4th century and found in one of the tombs) illustrates the names of early Christian notables. Another highlight is the headless white-marble statue of the Hellenic goddess Tyche, which was found sitting in the front row of the West Theatre.

map Google map; West along the decumanus maximus are the overgrown public baths. Built in the 4th century, this would once have been an impressive complex of fountains (like the nearby nymphaeum, statues and baths, though little remains today after various earthquakes.

Tomb of ModestusTomb

The thick stone doors of this Roman tomb outside the main archaeological area still swing on ancient hinges. Nearby are the less notable tombs of Germani and Chaireas.

map Google map; The North Theatre is overgrown and missing much of its original black-basalt stones, which were recycled by villagers in other constructions, but it’s still fun to clamber about.

map Google map; The shells of a row of shops remain in the western section of what was once the colonnaded courtyard of the Basilica Terrace.

map Google map; This public water fountain, once a two-storey complex with a large covered cistern, has niches for statues of the water goddesses.

map; Surrounding the museum are the comprehensive ruins of an Ottoman village dating from the 18th and 19th centuries. Two houses, Beit Malkawi (now used as an office for archaeological groups) and the nearby Beit Heshboni, are still intact. An Ottoman mosque and the remains of a girls’ school are also worth a cursory visit if you choose to amble around the derelict lanes. The village was inhabited until the 1980s, when the residents were evicted to allow archaeological excavations at Gadara.

map Google map; A bit of imagination is needed to reconstruct the colonnaded courtyard of the Basilica Terrace, the western section of which housed a row of shops. The remains of a 6th-century church, with an unusual octagonal interior sanctum, are marked today by the remaining basalt columns. The church was destroyed by earthquakes in the 8th century.

map Google map; This small mosque, no longer consecrated, is at the heart of the old Ottoman village of Umm Qais.

Roman MausoleumsTomb

The decumanus maximus continues west of the main site for 1km or so, leading to some ruins of limited interest, including baths, mausoleums and gates. Japanese and Iraqi archaeologists are currently excavating here. Most interesting is the basilica built above one of the Roman mausoleums. You can peer into the subterranean tomb through a hole in the basilica floor. The sarcophagus of Helladis that once lay here can be seen in the Museum of Anthropology & Archaeology in Irbid.

4Sleeping