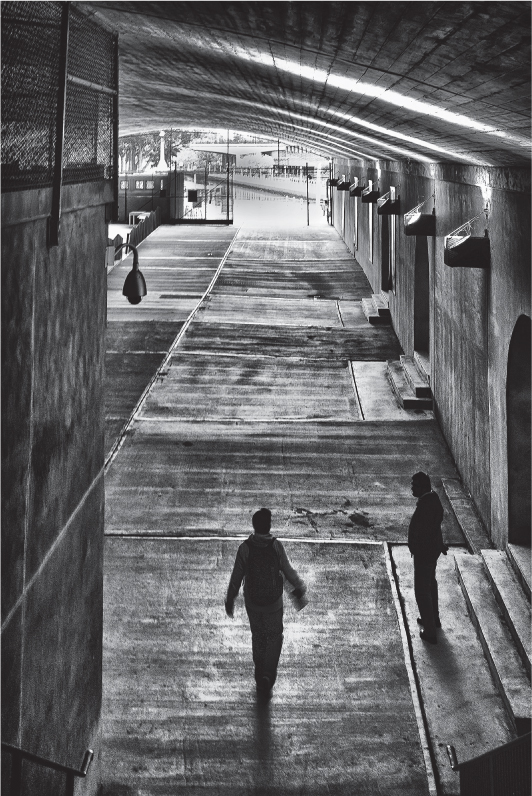

Rendezvous – Philip Rice (pjr)

The Shooting Menu settings are the most-used functions in the camera. Spend time carefully learning about each of these selections because you’ll use them often. They affect how your camera takes pictures in all sorts of ways.

The following is a list and overview of the 25 items found on the D610 Shooting Menu:

• Reset shooting menu – Restores the factory default settings in the Shooting Menu for the currently selected User setting.

• Storage folder – Selects which folder subsequent images will be stored in on the memory card(s).

• File naming – Lets you change three characters of the image file name so it is personalized.

• Role played by card in Slot 2 – Allows you to select how the camera divides image storage between Slot 1 and Slot 2.

• Image quality – Selects from seven image quality types, such as JPEG fine or NEF (RAW).

• Image size – Chooses whether to shoot Large (6016 × 4016, 24.2 M), Medium (4512 × 3008, 13.6 M), or Small (3008 × 2008, 6.0 M) images.

• Image area – Chooses if the camera automatically selects DX mode when a DX lens is mounted (Auto DX crop) and if it will shoot in FX (36 × 24) or DX (24 × 16) mode.

• JPEG compression – Selects Size priority or Optimal quality for your best JPEG images.

• NEF (RAW) recording – Sets the compression type and bit depth for NEF (RAW) files.

• White balance – Chooses from nine different primary White balance types, including several subtypes, and includes the ability to measure the color temperature of the ambient light (Preset manual).

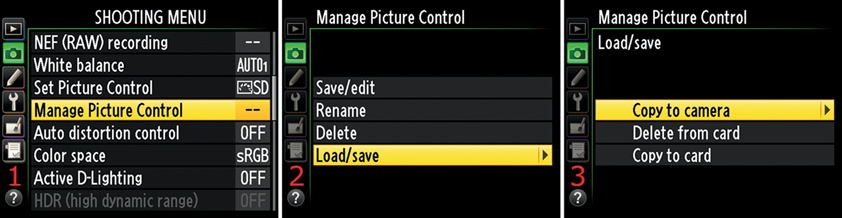

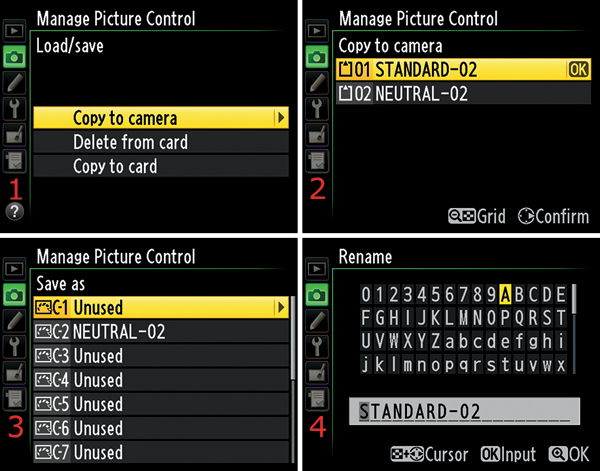

• Set Picture Control – Chooses from six Picture Controls that modify how the pictures look.

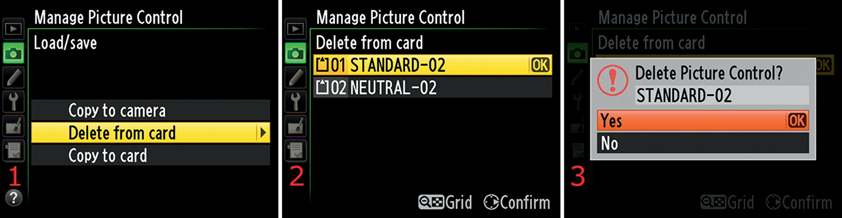

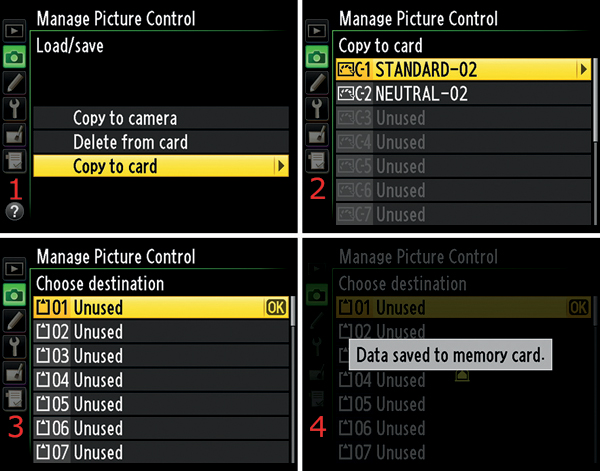

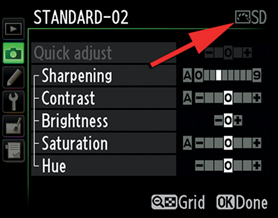

• Manage Picture Control – Saves, loads, renames, or deletes custom Picture Controls on your camera’s internal memory or card slots.

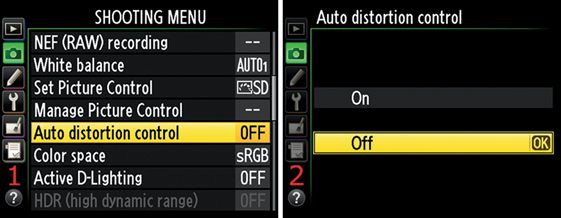

• Auto distortion control – Causes the camera to look for barrel and pincushion distortion and attempts to automatically correct it. Recommended for G and D lenses only.

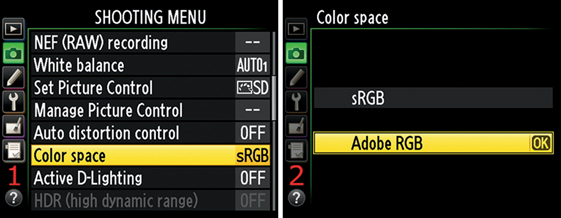

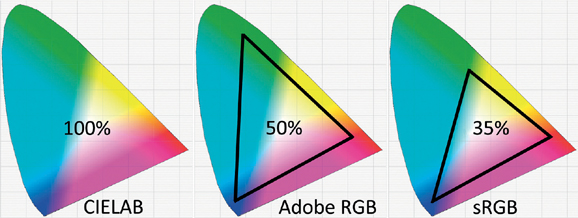

• Color space – Selects the printing industry standard, Adobe RGB, or the Internet and home use standard, sRGB.

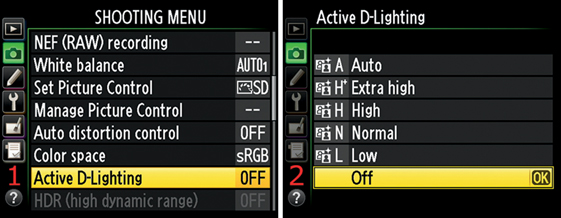

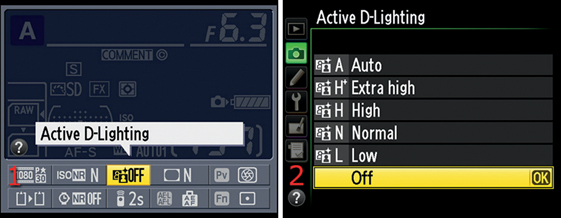

• Active D-Lighting – Allows you to select from several levels of automatic contrast correction for your images. The camera itself will protect your images from a certain degree of under- or overexposure while extending the camera’s dynamic range.

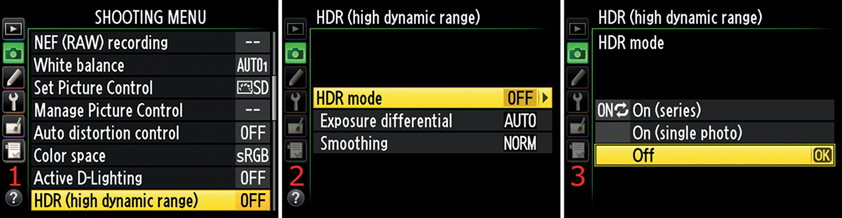

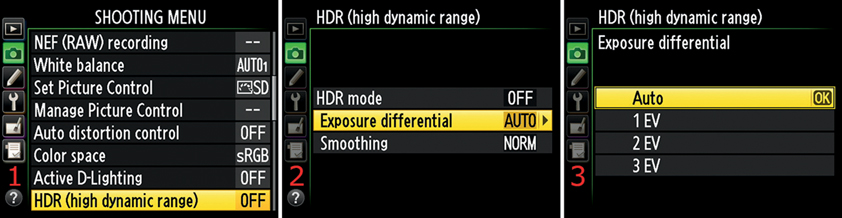

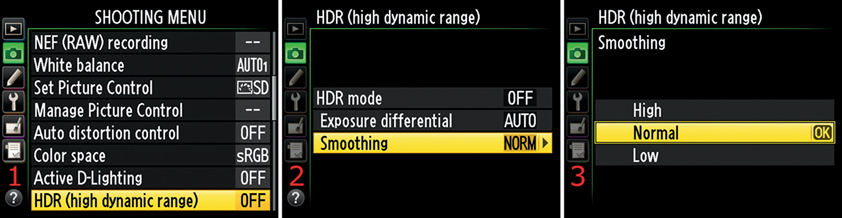

• HDR (high dynamic range) – Allows you to control the overall contrast in the image to provide a wider dynamic range by automatically combining—in the camera—two pictures taken at different exposures. Each image can have from 1 to 3 EV difference in exposure.

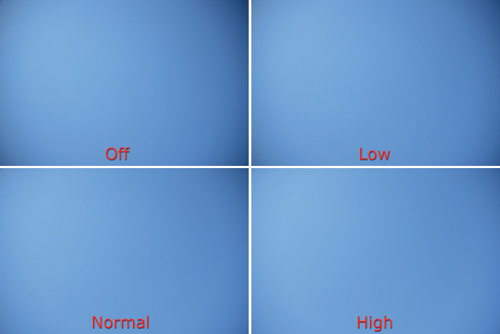

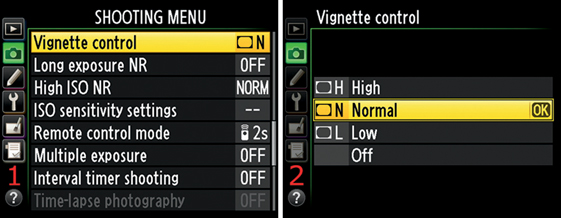

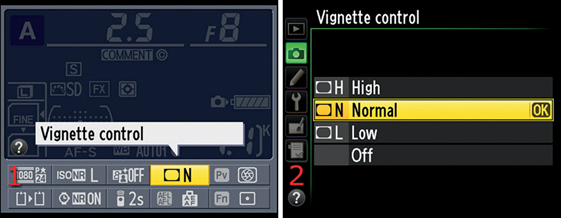

• Vignette control – Lets you automatically remove the darkening at the corners and edges of pictures taken with wide-open lens apertures.

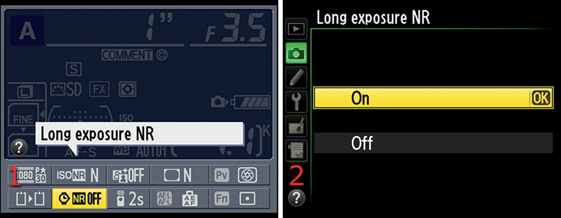

• Long exposure NR – Uses the black-frame subtraction method to significantly reduce noise in long exposures.

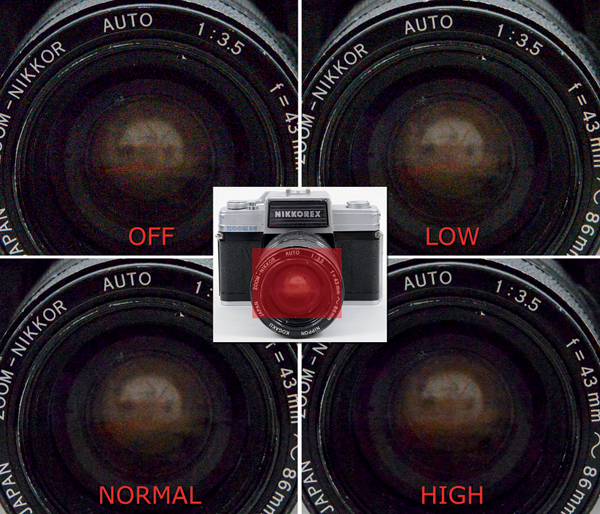

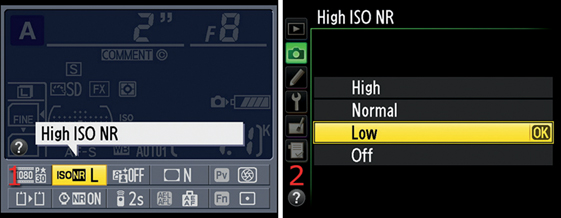

• High ISO NR – Uses a blurring method, with selectable levels, to remove noise from images shot with high ISO sensitivity values.

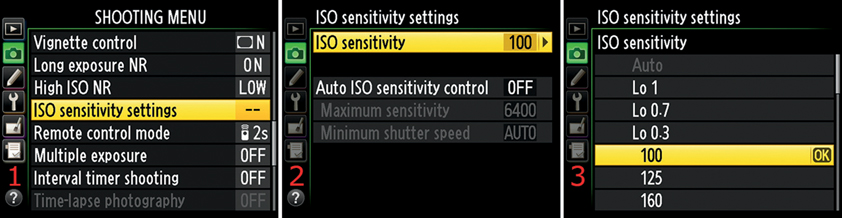

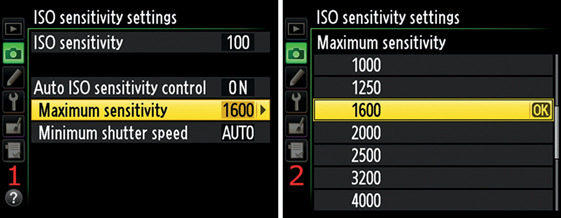

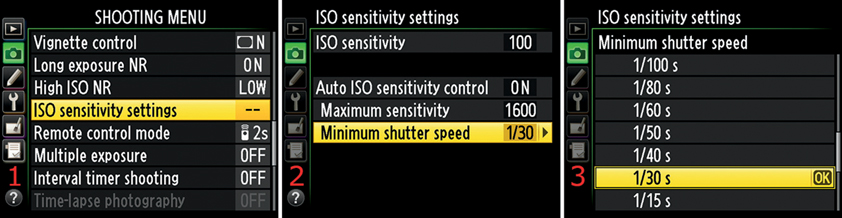

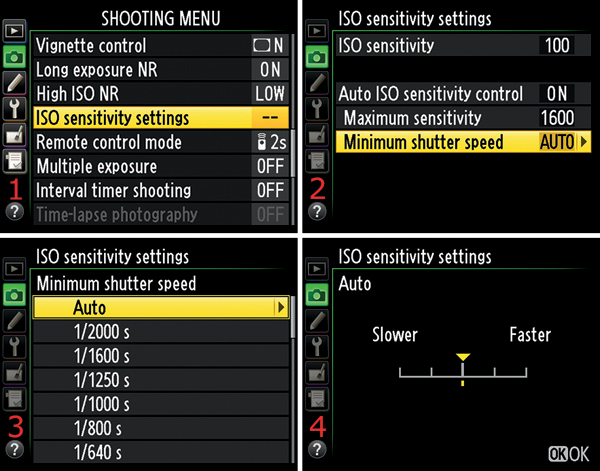

• ISO sensitivity settings – Allows you to select the camera’s ISO sensitivity, from ISO 50 (Lo 1) to ISO 25,600 (Hi 2), or you can let the camera decide automatically.

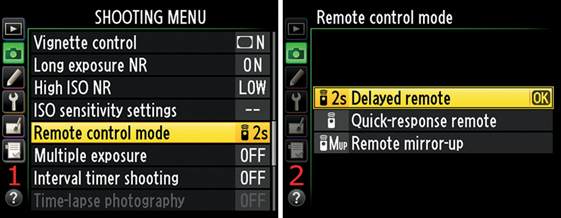

• Remote control mode – Gives you remote control of your camera so you can use a Nikon ML-L3 wireless remote to control the camera in various ways, including mirror-up shooting. This control can be used to replace a standard release cable.

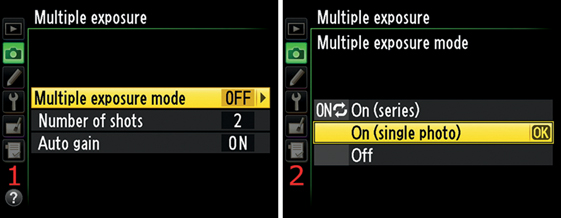

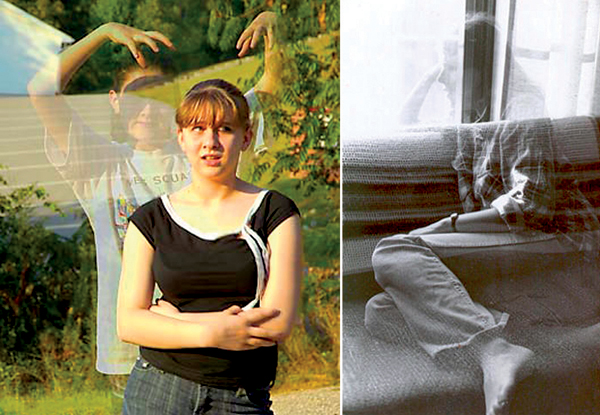

• Multiple exposure – Allows you to take more than one exposure in a single frame and then combine the exposures in interesting ways.

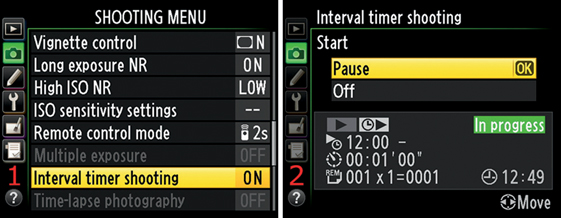

• Interval timer shooting – Allows you to put your camera on a tripod and set it to make one to several exposures at customizable time intervals.

• Time-lapse photography – Similar to Interval timer shooting, except more movie oriented. Allows you to make a time-lapse movie with the options selected in Shooting Menu > Movie settings. Shooting things like a time exposure of a flower opening, clouds moving across the sky, or star trails is easy with the D610.

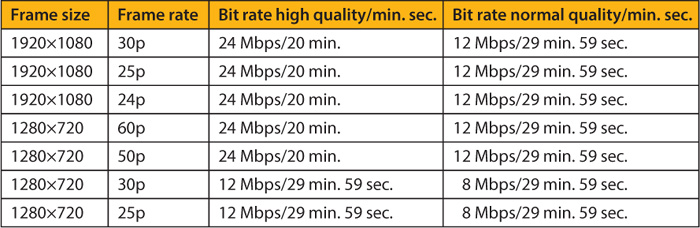

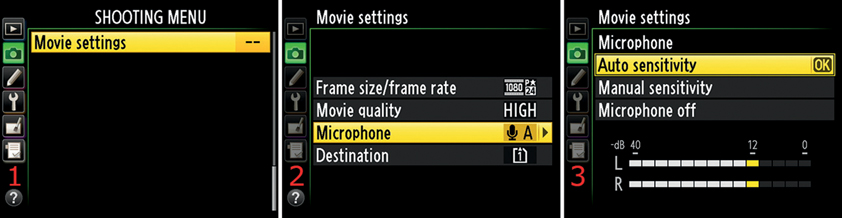

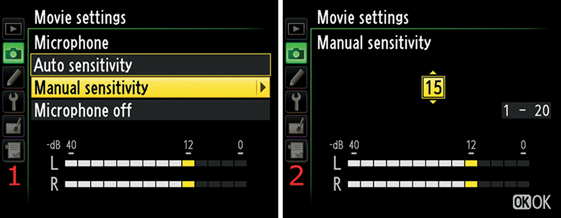

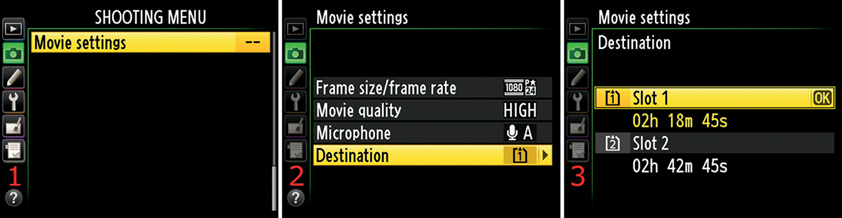

• Movie settings – Sets the Frame size, Frame rate, and Quality of the video stream in Movie mode. Also selects how the Microphone works and the Destination card slot for movies.

Each of these items can be configured and saved for later recall by using the two available User settings on the D610 Mode dial (U1 and U2).

(User’s Manual – Page 81)

User settings U1 and U2 are memory locations to which you can assign specific camera configurations that you would like to save for future use. Let’s briefly discuss how U1 and U2 work (more information can be found in chapter 5, Setup Menu).

Figure 3.0 – U1 and U2 user settings

If you configure your camera’s internal settings in a particular way and want to save that setup, simply go to the Setup Menu and select Save user settings > Save to U1 [or U2] > Save settings. This is optional, in case you don’t want to use U1 and U2 on the Mode dial (figure 3.0). However, it is a very convenient way to configure your camera for specific shooting situations so you can change setups quickly.

For instance, with my D610, I set user setting U1 as my high-quality setting. I shoot in NEF (RAW) Image quality with Lossless compressed and 14-bit depth in NEF (RAW) recording, Adobe RGB Color space, ISO 100, and Neutral Picture Control.

U2 is my party setting. I use JPEG fine Image quality with Size priority in JPEG compression, sRGB Color space, ISO 400 with Auto ISO sensitivity control set to On and Maximum sensitivity set to 800, and SD Picture Control.

The two user settings on the Mode dial allow you to store a lot more than just Shooting Menu items. They can also store a specific configuration for many other settings, such as the Custom settings in the Custom Setting Menu, exposure modes, flash, compensation, metering, AF-area modes, bracketing, and more. Nikon has given us a powerful and flexible way to configure our cameras for specific shooting needs.

We’ll discuss the detailed configuration of these two settings in the chapter titled Metering, Exposure Modes, and Histogram under the subheading U1 and U2 User Settings. For now, just keep in mind that you can save the settings you make to the upcoming Shooting Menu items in a cumulative way within user settings U1 and U2 on the Mode dial. After you configure many aspects of your camera, you can save the changes with Setup Menu > Save user settings > U1 (or U2) > Save settings.

You can make changes to the camera’s settings at any time outside of the U1 and U2 Mode dial positions with no effect on the two user settings. When you select U1 or U2 on the Mode dial, those settings outside of U1 or U2 will be overridden—but not overwritten—by your chosen user setting. In other words, if your camera is configured in a certain way for general use outside of the two user settings, and then you select U1 or U2, the user settings do not overwrite the current configuration. Instead they toggle the settings you’ve saved in U1 or U2. When you exit U1 or U2, the camera reverts to however it was previously configured outside of the user setting.

Basically, you can configure the camera in up to three separate ways: U1 and U2, and however you have the camera configured outside of the two user settings.

There are several Shooting Menu options that cannot be stored and saved in the user settings:

• Storage folder

• File naming

• Manage Picture Control

• Multiple exposure

• Interval timer shooting

These five Shooting Menu functions are independent of the user settings that you can save. If you modify one of these five functions, it will function the same way no matter what user setting you have selected. We will discuss how to save user settings in the chapter titled Setup Menu, under the subheading called Save User Settings.

Now, let’s examine how to configure the camera’s Shooting Menu settings.

(User’s Manual – Page 214)

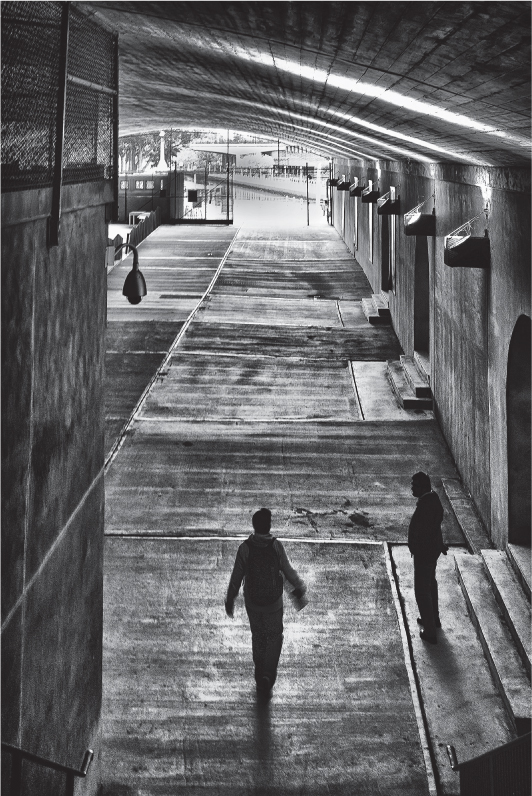

Press the MENU button on the back of your D610 to locate the Shooting Menu, which corresponds to a green camera icon in the toolbar on the left side of the Monitor (figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1 – The Shooting Menu is the camera’s most often-used menu

We’ll now examine each of the settings on the Shooting Menu. Have your camera in hand, and maybe even the User’s Manual if you are interested in what it says about certain settings (page numbers provided). Remember that it’s entirely optional to use the User’s Manual. This book is a comprehensive reference, but sometimes I like to get an alternate view. The User’s Manual, although somewhat dense, is still a good reference.

If you take time to think about and configure each of these settings at least once, you’ll learn a lot more about your new camera. There are a lot of settings to learn about, but don’t feel overwhelmed. Some of these settings can be configured and then forgotten, and you’ll use other settings more often. We’ll look at each setting in detail to see which ones are most important to your style of shooting.

(User’s Manual – Page 214)

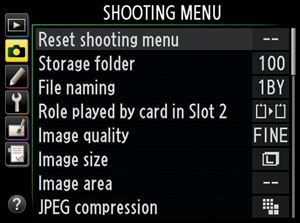

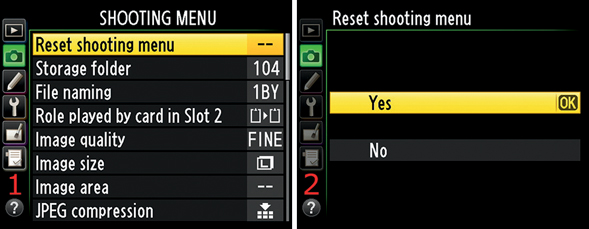

Be careful with this selection. Reset shooting menu does what it says—it resets the Shooting Menu, only for the currently selected user setting (U1, U2, or outside the user settings), back to the factory default configuration (figure 3.2). If you have U1 selected on the Mode dial, it resets only U1, and so forth.

Figure 3.2 – Reset shooting menu

This is a rather simple process. Here are the steps to reset the Shooting Menu:

1. Select Reset shooting menu and scroll to the right (figure 3.2, screen 1).

2. Choose Yes or No (figure 3.2, screen 2).

3. Press the OK button.

Note: This function resets all Shooting Menu functions, including the five settings that cannot be saved in a User setting: Storage folder, File naming, Manage Picture Control, Multiple exposure, and Interval timer shooting. This may be a problem if you have carefully configured one of the five settings and then you answer Yes to Reset shooting menu because your settings will be lost.

Interval timer shooting will warn you with a screen that says, This will end interval timer shooting. Ok? You can select No to stop the reset action.

Settings Recommendation: This is an easy way to start fresh with a particular User setting since it’s a full reset of all the values, including the five special settings. I use this when I purchase a preowned camera and want to clear someone else’s settings or if I simply want to start fresh. If you use any of the five nonsaveable settings regularly, be aware that Reset shooting menu will reset them.

(User’s Manual – Page 215)

Storage folder allows you to either create a new folder for storing images or select an existing folder from a list of folders. The D610 automatically creates a folder on its primary memory card called something similar to 100ND610. The folder can hold up to 999 images. You’ll see the full name of the folder only when you examine the memory card in your computer—check in the digital camera images (DCIM) folder on the memory card.

When the camera senses that the current folder contains 999 images and you take another picture, the new image is written to a new folder that is a seamless continuation of the previous folder. The first three digits of the new folder name is increased by one. For example, if you are using a folder named 100ND610, the camera will automatically create a new folder called 101ND610 when you exceed 999 images in the original folder.

If you want to store images in separate folders on the memory card, you might want to create a new folder, such as 200ND610. Each folder you create can hold 999 images, and you can select any folder as the default by choosing Storage folder > Select folder from list (discussed in the next subsection). This is a nice way to isolate certain types of images on a photographic outing. Maybe you’ll put landscape shots in folder 300ND610 and people shots in 400ND610. You can develop your own numbering system and implement it with this function.

When you manually create folder names, you may want to leave room for the camera’s automatic folder creation and naming. If you try to create a folder name that already exists, the camera doesn’t give you a warning; it simply switches to the existing folder. Let’s look at how to create a new folder with a number of your choice, from 100 to 999 (100ND610 to 999ND610).

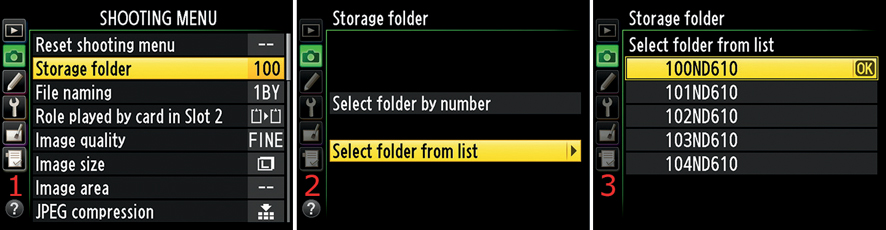

Figure 3.3 – Storage folder – Select folder by number

Here are the steps to manually create a new folder:

1. Select Storage folder and scroll to the right (figure 3.3, screen 1).

2. Choose Select folder by number and scroll to the right (figure 3.3, screen 2).

3. You’ll now see a screen that allows you to create a new folder number from 100 to 999 (figure 3.3, screen 3). Create your number using the Multi selector, then press the OK button.

Settings Recommendation: You cannot create a folder numbered 000 to 099; I tried! Remember that the three-digit number you select will have ND610 appended to it and it will look something like 101ND610 or 301ND610 when you have finished. After you have created a new folder, the camera will automatically switch to it.

What if you want to simply start using an existing folder instead of making a new one? You may have already created a series of folders and want to switch among them to store different types of images. It’s easy with the following screens and steps.

Figure 3.4 – Storage folder – Select folder from list

Use the following steps to select an existing folder:

1. Select Storage folder and scroll to the right (figure 3.4, screen 1).

2. Scroll down to Select folder from list and scroll to the right (figure 3.4, screen 2). If this selection is grayed out, there is only one folder on the memory card. You’ll need to create a new folder with the instructions found in the previous section.

3. You’ll see the available folders displayed in a list that looks like the one shown in figure 3.4, screen 3. Select one of the folders from the list. I happen to have six folders—100ND610 to 105ND610—on my current memory card.

4. Press the OK button. The camera will switch back to the Shooting Menu main screen, with the new folder number displayed to the right of Storage folder.

All new images will be saved to this folder until you exceed 999 images in the folder or manually change to another folder. One note of caution: If you are using folder 999ND610 and the camera records the 999th image, or if it records image number 9999—the Shutter-release button will be disabled until you change to a different folder. Nikon warns that the camera will be slower to start up if the memory card contains “a very large number of files or folders.”

Figure 3.4.1 – Three folder conditions: Screen 1, no images (no folder); Screen 2, folder empty; Screen 3, folder partially full

Note: There is also a fourth condition—not shown in figure 3.4.1—that displays an icon of a full folder, which means there are 999 images in the folder or it contains an image numbered 9999. You cannot write any more images to a folder when it is full.

If you try to write to a folder containing an image ending with the number 9999, you could cause the camera to lock its Shutter-release button until another memory card is inserted or the current card is formatted.

Settings Recommendation: As memory cards get bigger and bigger, I can see a time when this functionality will become very important. Last year I shot around 150 GB of image files. With the newest memory cards now hitting 256 GB, I can foresee a time when the card(s) in my camera will become a months-long backup source.

I don’t use the Storage folder very much, but I will in the near future. This is a good function to learn how to use!

(User’s Manual – Page 216)

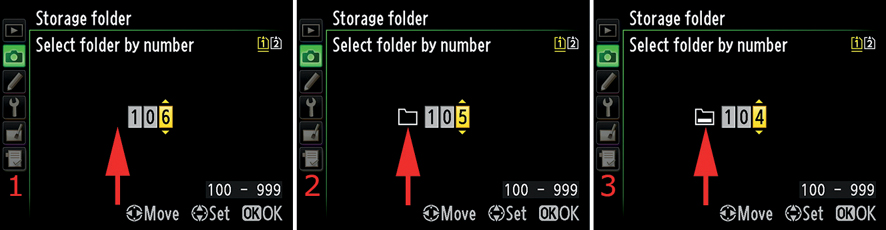

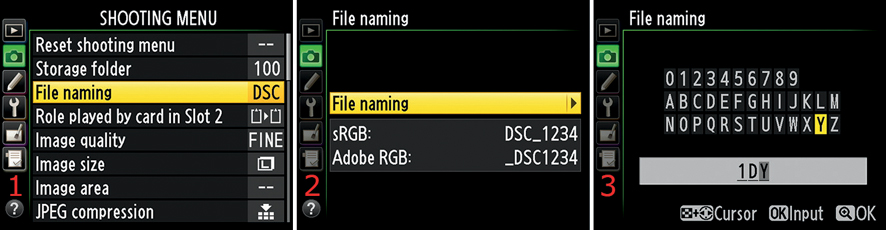

File naming allows you to control the first three characters of the file name for each of your images. The default is DSC, but you can change it to any three alphanumeric characters.

The camera defaults to the following File naming for your images:

• When using sRGB Color space: DSC_1234

• When using Adobe RGB Color space: _DSC1234

You can see that depending on which Color space you are using, the camera adds an underscore to one side of the three characters (figure 3.5, screen 2).

I use this feature in a special way. Since the camera can count images in a File number sequence from 0001 to 9999, I use File naming to help me personalize my images. The camera cannot count higher than 9,999. Instead, it rolls back to 0001 for the 10,000th image.

When I first got my D610, I changed the three default characters from DSC to 1DY. The 1 tells me how many times my camera has passed 9,999 images, and DY is my initials, thereby helping me protect the copyright of my images in case they are ever stolen and misused.

Since the camera’s image File number sequence counter rolls back to 0001 when you exceed 9,999 images, you need a way to keep from accidentally overwriting images from the first set of 9,999 images you took. I use this method:

• First 9,999 images |

1DY_0001 through 1DY_9999 |

• Second 9,999 images |

2DY_0001 through 2DY_9999 |

• Third 9,999 images |

3DY_0001 through 3DY_9999 |

See how simple it is? This naming method shows a range of nearly 30,000 images. Since the D610’s shutter is tested to a professional level of 150,000 cycles, you will surely need to use a counting system like this one. My system works up to only 89,991 images (9,999 × 9). If you use this counting system and start your camera at 0 (0DY_0001 through 0DY_9999), you can count up to 99,990 images.

If Nikon would give us just one extra digit in the image counter, we could count in sequences of just under 100,000 images instead of 10,000 images. I suppose that many of us will have traded up to the next Nikon DSLR before we reach enough images that this really becomes a constraint. On my Nikon D2X that I’ve used since 2004, I’ve shot close to 40,000 images.

Custom setting d7 File number sequence in the D610 controls the File number sequence setting. That function works along with File naming to let you control how your image files are named. If File number sequence is set to Off, the D610 will reset the four-digit number—after the first three custom characters in File naming—to 0001 each time you format your memory card. I set File number sequence to On as soon as I got my camera so it would remember the sequence all the way up to 9,999 images. I want to know exactly how many pictures I’ve taken over time. We’ll talk more about File number sequence in the chapter titled Custom Setting Menu.

Here are the steps to set up your custom File naming characters:

1. Select File naming from the Shooting Menu and scroll to the right (figure 3.5, screen 1).

2. Select File naming and scroll to the right (figure 3.5, screen 2).

3. Use the Multi selector to scroll through the numbers and letters to find the characters you want to use. Press the OK button on the D610 to select and insert a character. To correct an error, hold down the Playback zoom out/thumbnails button and use the Multi selector to scroll to the character you want to remove. Press the Delete button to delete the bad character.

4. Press the Playback zoom in button to save your three new custom characters. They will now be the first three characters of each image file name.

Now you’ve customized your camera so the file names reflect your personal needs.

Settings Recommendation: I discussed how I use the three custom characters in the beginning of this section. You may want to use all three of your initials or some other numbers or letters. Some people leave these three characters at their default. I recommend using your initials, at a minimum, so you can easily identify the images as yours. With my family of Nikon shooters it sure makes it easier! If you use my method, be sure to watch for the images to reach 9999 and rename the first character for the next sequence of 9,999 images.

(User’s Manual – Page 96)

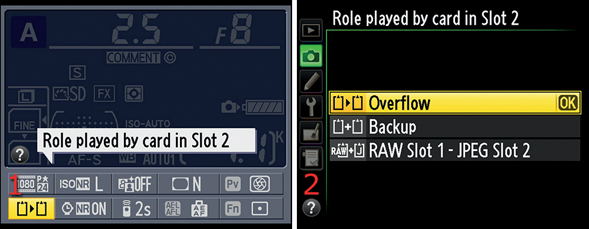

Role played by card in Slot 2 is designed to let you control the flow of images to the camera’s memory cards. You can decide how and to which card(s) the camera writes image files. Slot 1 is the top card slot when you open the Memory card slot cover, and Slot 2 is on the bottom.

Here is a description of the three ways you can configure the Role played by card in Slot 2 setting:

• Overflow – Have you ever gotten the dreaded Card full message? If you select Overflow, it will take a lot longer to get this message. Overflow writes all images to the card you have selected under Primary slot selection. Then when the card in Slot 1 is full, the rest of the images are sent to the card in Slot 2. The image number shown on the Control panel and in the Viewfinder will count down as you take pictures and they are written to the card in Slot 1. When the image count nears zero, the camera will switch to the card in Slot 2, and the available image count number on the Control panel will increase to however many images will fit on the second card. It is not necessary to use the same size card when using this function. The camera will merely fill up all available space on both cards as you take pictures.

• Backup – This function is a backup for critical images. Every image you take is written to the memory cards in Slot 1 and Slot 2 at the same time. You have an automatic backup system when you use the Backup function. If you are a computer geek (like me), you’ll recognize this as RAID 1 or drive mirroring. Since your camera is very much a computer, a function like this is great to have. Be sure that both cards are of equal capacity or that the card in Slot 2 is larger than the card in Slot 1 when you use this function. Otherwise the capacity shown on the Control panel and in the Viewfinder will be reduced. Since the camera will write a duplicate image to each card, the smallest card sets the camera’s maximum storage capacity. When either card is full, the Shutter-release button becomes disabled.

• RAW Slot 1–JPEG Slot 2 – If you like to shoot NEF (RAW) files, this function can save you some time. You’ll have a JPEG for immediate use and a RAW file for post-processing. When you take a picture, the camera will write the RAW file to the card in Slot 1 and a JPEG file to the card in Slot 2. There is no choice in this arrangement; RAW always goes to the primary card and JPEG always goes to the secondary card. This function works only when you have Shooting Menu > Image quality set to some form of NEF (RAW) + JPEG. If you set Image quality to just NEF (RAW) or just JPEG fine—instead of NEF (RAW) + JPEG fine, for example—the camera will write a duplicate file to both cards, like the Backup function.

Figure 3.6 – Role played by card in Slot 2

The steps to choose the Role played by card in Slot 2 are as follows:

1. Select Role played by card in Slot 2 from the Shooting Menu and scroll to the right (figure 3.6, screen 1).

2. Choose one of the three selections discussed previously (figure 3.6, screen 2).

3. Press the OK button.

You can also open the Role played by card in Slot 2 screen by using a menu selection from the Information display edit screen, as shown in figure 3.6.1.

Figure 3.6.1 – Role played by card in Slot 2 from the Information display edit screen

Simply press the Info button twice to open the Information display edit screen. Select the Role played by card in Slot 2 icon (figure 3.6.1, screen 1) and press the OK button. Now, follow steps 2 and 3 that accompany figure 3.6.

Settings Recommendation: When I’m out shooting for fun or for any type of photography where maximum image capacity is of primary importance, I select Overflow. This causes the camera to fill up the primary card and then automatically switch to the secondary card for increased image storage. If I’m shooting images that I cannot afford to lose, such as at a unique event like a wedding or a baptism, I often use the Backup function for automatic backup of every image.

If I want both a RAW and JPEG file, I use the RAW Slot 1–JPEG Slot 2 function. This lets me have the best of both worlds when card capacity is not a concern, and it gives me redundancy, like Backup. In a sense, RAW Slot 1–JPEG Slot 2 backs up your images; they are just in different formats. I use each of these selections from time to time, but my favorite is Overflow.

(User’s Manual – Page 93)

Image quality is simply the type of image your camera can create, along with the amount of image compression that modifies picture storage sizes.

You can shoot several distinct image formats with your D610. We’ll examine each format in detail and discuss the pros and cons of each as we go. When we’re done, you’ll have a better understanding of the formats, and you can choose an appropriate one for each of your shooting styles. The camera supports the following seven Image quality types:

• NEF (RAW) + JPEG fine

• NEF (RAW) + JPEG normal

• NEF (RAW) + JPEG basic

• NEF (RAW)

• JPEG fine

• JPEG normal

• JPEG basic

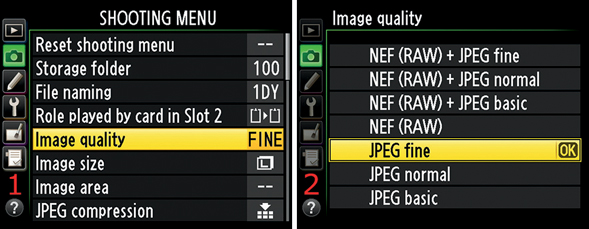

The steps to select an Image quality setting are as follows:

1. Select Image quality from the Shooting Menu and scroll to the right (figure 3.7, screen 1).

2. Choose one of the seven Image quality types. Figure 3.7, screen 2, shows JPEG fine as the selected format.

3. Press the OK button to select the format.

Figure 3.7 – Choosing an Image quality setting with menus

You can also use the QUAL button (Playback zoom in button) to set the Image quality (and size). The steps are as follows:

1. Hold down the QUAL button (figure 3.8, image 1).

2. Rotate the Main command dial to change the Image quality (bottom red arrow in figure 3.8, image 2). Also use the Sub-command dial (top red arrow in figure 3.8, image 2) to change the Image size.

3. Look at the Control panel to see the Image quality and Image Size values change. The bottom red arrow in figure 3.8, image 3, shows the quality (e.g., RAW, FINE, RAW+FINE), and the top red arrow shows the size (L, M, S).

4. Release the QUAL button to lock in the settings.

Figure 3.8 – Choosing an Image quality setting with external controls

Let’s look at each of these formats and see which ones you might want to use regularly. We’ll go beyond how to turn the different formats on and off and discuss why and when you might want to use a particular format. Even though the Image quality list shows seven different entries, the camera really shoots in only two formats: NEF (RAW) and JPEG.

The first three selections on the Image quality list (figure 3.7, screen 2) allow the camera to take a NEF (RAW) file and a JPEG fine, normal, or basic file at the same time. Fine, normal, and basic indicate three levels of compression that are available for the JPEG format. When you press the Shutter-release button with one of the three NEF (RAW) + JPEG Image quality modes selected, the camera creates a RAW file and a JPEG file and writes them to the memory card(s) as separate files. To understand how they work, we’ll examine the NEF (RAW) and JPEG formats.

The Nikon NEF proprietary format stores raw image data directly onto the memory card. Most of the time photographers refer to a NEF file simply as a RAW file. These RAW files can easily be recognized because the file name ends with NEF. This image format is not used in day-to-day graphics work (like the JPEG format), and it’s not even an image yet. Instead, it’s a base storage format used to hold images until they are converted to another file format ending in something like JPG, TIF, EPS, or PNG. Other than the initial compression—as selected in Shooting Menu > NEF (RAW) recording—NEF stores all available image data and can easily be manipulated later.

You must use conversion software—such as Nikon ViewNX 2, Nikon Capture NX2, Adobe Photoshop Lightroom, or Adobe Photoshop—to convert your NEF-format RAW files into other formats. You can download the latest version of the free Nikon ViewNX 2 and all sorts of Nikon imaging software from the following Nikon website:

http://support.nikonusa.com/app/answers/detail/a_id/61/~/current-versions-of-nikon-software

The Nikon CD that comes with your camera contains Nikon ViewNX 2, which you can use immediately for RAW conversion. However, I recommend using the link to the Nikon website for downloading the latest version. Alternately, you can install Nikon ViewNX 2 from the Nikon CD and then click the Help menu, where you will find a link to check Nikon’s website and update the software, if needed.

There are also several aftermarket RAW conversion software packages available. Do a Google search of “Nikon RAW conversion software” for a listing.

Before you shoot in NEF (RAW) format, it’s a good idea to install your RAW conversion software of choice so you’ll be able to view, adjust, and save the images to another format when you are done shooting. You may not be able to view NEF files directly on your computer unless you have RAW conversion software installed.

Some operating systems provide a downloadable patch or codec (coder-decoder) that lets you see NEF files as small thumbnails in the file manager software (e.g., Windows Explorer or Mac OS X Finder).

Do a Google search on these specific words to start your search for available codecs: “download Nikon NEF RAW viewer.” You will find free codecs for Windows 7 and 8, Vista, XP, and Mac OS X. However, be careful that you don’t go to a website that promises the moon and delivers malware instead.

Nikon lists a free codec for Windows 7 and 8 (32 and 64 bit), Windows Vista (32 and 64 bit, Service Pack 2), and Windows XP (32 bit only, Service Pack 3) at this website:

http://nikonimglib.com/nefcodec/

Note: There are also reliable third-party companies, such as Ardfry Imaging LLC (http://www.ardfry.com/nef-codec/), that offer various 32- and 64-bit RAW codecs for a small fee.

Unfortunately, there is a greater selection of codecs for Windows than for Mac. However, with so many software developers out there, things change constantly.

The Nikon CD that came with your camera contains software for both Mac OS X and Windows. Nikon ViewNX 2 RAW conversion software is supplied free with the D610, but Nikon Capture NX2 requires a separate purchase. Capture NX2 has become my favorite conversion and post-processing software, along with Adobe Photoshop.

Now, let’s talk about NEF, or RAW, quality. I use the NEF (RAW) format most of the time. I think of a RAW file like I thought of my slides and negatives a few years ago. It’s my original image that must be saved and protected.

It’s important that you understand something very different about NEF (RAW) files. They’re not really images—yet. Basically, a RAW file is composed of black-and-white or sensor data and camera setting information markers. The RAW file is saved in a form that must be converted to another file type to be used in print or on the web.

When you take a picture in RAW format, the camera records the image data from the sensor and stores markers for how the camera’s color, sharpening, contrast, saturation, and so forth are set, but it does not apply the camera setting information to the image. In your computer post-processing software, the image will appear on-screen with the settings you initially configured in your D610. However, these settings are applied temporarily for your computer viewing pleasure.

For example, if you don’t like the white balance you selected at the time you took the picture, simply apply a new white balance and the image will appear as if you had used that setting when you took the picture. If you initially shot the image using the Standard Picture Control and now want to use the Vivid Picture Control, all you have to do is apply it—with Nikon ViewNX 2 or Nikon Capture NX2—before the final conversion and it will be as if you used the Vivid Picture Control when you first took the picture.

This is quite powerful! Virtually no camera settings are applied to a RAW file in a permanent way. That means you can apply completely different settings to the image in your computer software and it will appear as if you had used those settings when you first took the picture. This allows a lot of flexibility later.

NEF (RAW) is generally used by individuals who are concerned with maximum image quality and who have time to convert the images. A conversion to JPEG sets the image markers permanently, and a conversion to TIFF sets the markers but allows you to modify the image later. Unfortunately, the TIFF format creates very large file sizes.

Here are the pros and cons of NEF (RAW) format:

• Allows the manipulation of image data to achieve the highest-quality image available from the camera.

• All original details stay with the image for future processing needs.

• No conversions, sharpening, sizing, or color rebalancing will be performed by the camera. Your images are untouched and pure!

• You can convert NEF files to any other image formats by using your computer’s much more powerful processor instead of your camera’s processor.

• You have much more control over the final look of the image since you, not the camera, make the final decisions about the appearance of the image.

• A 12-bit or 14-bit format provides maximum color information.

• Not often compatible with the publishing industry, except after conversion to another format.

• Requires post-processing with proprietary Nikon software or third-party software.

• Larger file sizes are created, so you must have larger storage media.

• There is no industry-standard RAW format. Each camera manufacturer has its own proprietary format. Adobe has developed a generic RAW format called digital negative (DNG) that is becoming an industry standard. You can use various types of software, such as Adobe Lightroom, to convert your RAW images to DNG if you desire.

• The industry standard for home and commercial printing is 8 bits, not 12 bits or 14 bits.

Now, let’s examine the most popular format on the planet: JPEG.

As shown in figure 3.7, screen 2, the D610 has three JPEG modes. Each mode affects the final quality of the image. Let’s look at each mode in detail:

• JPEG fine |

Compression approximately 1:4 |

• JPEG normal |

Compression approximately 1:8 |

• JPEG basic |

Compression approximately 1:16 |

Each JPEG mode provides a certain level of lossy image compression, which means that it permanently throws away image data as you select higher levels of compression (fine, normal, basic). The human eye compensates for small color changes quite well, so the JPEG compression algorithm works very well for viewing by humans. A useful thing about JPEG is that you can vary the file size of the image, via compression, without affecting the quality too much.

Here are details of the three JPEG modes:

• JPEG fine (or fine-quality JPEG) uses a 1:4 compression ratio. If you decide to shoot in JPEG, this mode will give you the best-quality JPEG your camera can produce.

• JPEG normal (or normal-quality JPEG) uses a 1:8 compression ratio. The image quality is still very acceptable in this mode. If you are shooting at a party for a 4 ×6-inch (10 ×15 cm) image size, this mode will allow you to make lots of images.

• JPEG basic (or basic-quality JPEG) uses a 1:16 compression ratio. These are still full-size files, so you can surely take a lot of pictures. If you are shooting for the web or just want to document something well, this mode provides sufficient quality.

Note: It’s hard to specify an exact number of images that a particular card size will hold. My D610 reports that 151 lossless compressed NEF (RAW) images will fit on an 8 GB memory card, yet when the card is full I often have more than 300 images. With the higher compression ratio of JPEG files, it is even harder to predict exactly. The complexity within a scene has a lot to do with the final compressed file size. That’s why the camera underreports the number of images it can hold. You’ll find that your memory cards will usually hold many more images than the estimate presented by the camera.

The JPEG format is used by individuals who want excellent image quality but have little time for, or interest in, post-processing or converting images to another format. They want to use images immediately when they come out of the camera, with no major adjustments.

The JPEG format applies your chosen camera settings to the image when it is taken. The image comes out of the camera ready to use, as long as you have exposed it properly and have configured all the other settings appropriately.

Since JPEG is a lossy format, you cannot modify and save a JPEG file more than a time or two before compression losses ruin the image. A person who shoots a large number of images or doesn’t have the time to convert RAW images will usually use JPEG. That encompasses a lot of photographers.

Nature photographers might want to use NEF (RAW) since they have more time for processing images and wringing the last drop of quality out of them, but event or journalist photographers on a deadline may not have the time for, or interest in, processing images, so they often use the JPEG format.

Here are the pros and cons of capturing JPEG images:

• Allows for the maximum number of images on a memory card and computer hard drive.

• Allows for the fastest transfer from the camera memory buffer to a memory card.

• Compatible with everything and everybody in imaging.

• Uses the printing industry standard of 8 bits.

• Produces high-quality, first-use images.

• No special software is needed to use the image right out of the camera (no post-processing).

• Immediate use on websites with minimal processing.

• Easy transfer across the Internet and as email attachments.

• JPEG is a lossy format.

• You cannot manipulate a JPEG image more than once or twice before it degrades to an unusable state. Every time you modify and save a JPEG image, it loses more data and quality because of data compression losses.

Some shooters use the three Image quality settings, shown in figure 3.7, screen 2, that save two images at the same time:

• NEF (RAW) + JPEG fine

• NEF (RAW) + JPEG normal

• NEF (RAW) + JPEG basic

These settings give you the best of both worlds because the camera saves a NEF file and a JPEG file each time you press the Shutter-release button. In NEF (RAW) + JPEG fine, my camera’s 8 GB single-card storage drops to about 180 images since it stores a NEF file and a JPEG file for each picture I take.

You can set Shooting Menu > Role played by card in Slot 2 to write the NEF (RAW) file to one card and the JPEG file to the other. You can use the NEF (RAW) file to store all the image data and later process it into a masterpiece, and you can use the JPEG file immediately with no adjustment.

The NEF (RAW) + JPEG modes have the same features as their stand-alone modes. In other words, a RAW file in NEF (RAW) + JPEG mode works like a RAW file in NEF (RAW) mode, and a JPEG file in NEF (RAW) + JPEG mode works like a JPEG fine, normal, or basic file without the NEF (RAW) file.

Which format do I prefer? Why, RAW, of course! But it does require a bit of commitment to shoot in this format. NEF (RAW) files are not yet images and must be converted to another format for use. Once converted, they can provide the highest quality images your camera can possibly create.

When shooting in RAW, the camera is simply an image-capturing device, and you are the image manipulator. You decide the final format, compression ratio, size, color balance, and so forth. In NEF (RAW) mode, you have the absolute best image your camera can produce. It is not modified by the camera’s software and is ready for your personal touch. No camera processing allowed!

If you get nothing else from this section, remember this: by letting your camera process images in any way, it modifies or throws away data. There is a finite amount of data for each image that can be stored in your camera, and later in your computer. With JPEG, your camera optimizes the image according to the assumptions recorded in its memory. Data is thrown away permanently, in varying amounts.

If you want to keep all the image data that was recorded with your images, you must store your originals in RAW format. Otherwise you’ll never again be able to access that original data to change how it looks. A RAW file is the closest thing to a film negative or transparency that your digital camera can make. That’s important if you would like to modify the image later. If you are concerned with maximum quality, you should probably shoot and store your images in RAW format. Later, when you have the urge to make another masterpiece out of the original RAW image file, you’ll have all of your original data intact for the highest-quality image. (Compressed NEF loses a little data during initial compression, but Lossless compressed does not. I use Lossless compressed. These RAW compression types will be considered in an upcoming section called NEF (RAW) Recording under the subheading Type.)

If you’re concerned that the RAW format may change too much over time to be readable by future generations, you might want to convert your images to TIFF or JPEG files. TIFF is best if you want to modify your files later. I often save a TIFF version of my best images in case RAW changes too much in the future. Interestingly, I can still read the NEF (RAW) format from my 2002-era Nikon D100 in Nikon ViewNX 2. Therefore, I think we are safe for a long time with our NEF (RAW) files.

Settings Recommendation: I shoot in NEF (RAW) format for my most important work and JPEG fine for the rest. Some people find that JPEG fine is sufficient for everything they shoot. Those individuals generally do not like working with files on a computer or do not have time for it. You’ll use both RAW and JPEG, I’m sure. The format you use most often will be controlled by your time constraints and digital workflow.

If you have been shooting in NEF (RAW) + JPEG mode with a single memory card inserted in the camera, the D610 will display only the JPEG image on the Monitor.

Also, NEF (RAW) images are always Large images. The next section will discuss Image size, which applies only to JPEG images. There are no Large, Medium, and Small NEF images. All RAW files are the maximum size for their format (FX or DX).

Finally, you may want to investigate the Retouch menu > NEF (RAW) processing function, which allows you to create a JPEG file from a NEF (RAW) file, in-camera, with no computer involved.

(User’s Manual – Page 95)

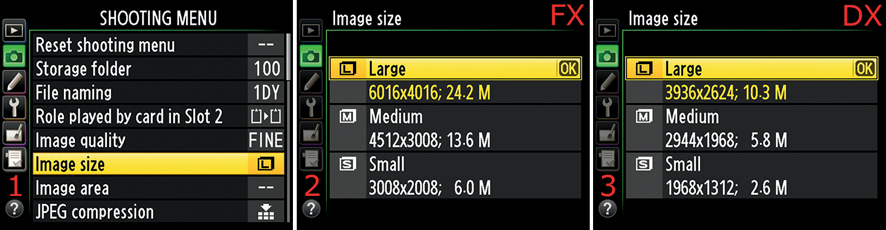

Image size lets you shoot with your camera set to various megapixel sizes. The default Image size setting for the D610 is Large, or 24.2 M (M = megapixels, shown elsewhere as MP). In FX Image area mode, you can change this rating from 24.2 M to 13.6 M or 6.0 M (figure 3.9, screen 2), or even smaller in DX Image area mode. Image size applies only to images captured in JPEG fine, normal, or basic modes.

If you’re shooting with your camera in any of the NEF (RAW) + JPEG modes, it applies only to the JPEG image in the pair. Image size does not apply to a NEF (RAW) image. This setting is relatively simple since it affects just the megapixel size of the image. Here are the three settings under Image size that are affected by the selected Image area, discussed in the next section:

• Large |

(6016 ×4016; 24.2 M) |

• Medium |

(4512 ×3008; 13.6 M) |

• Small |

(3008 ×2008; 6.0 M) |

• Large |

(3936 ×2624; 10.3 M) |

• Medium |

(2944 ×1968; 5.8 M) |

• Small |

(1968 ×1312; 2.6 M) |

Figure 3.9 – Choosing an Image size

The steps to select an Image size are as follows:

1. Select Image size from the Shooting Menu and scroll to the right (figure 3.9, screen 1).

2. Choose one of the three Image size settings. Figure 3.9, screens 2 and 3, show Large as the selected size. You will see only one of these last two screens, according to how you have Image area configured (next section). Screen 2 shows the Image size for FX Image area, and screen 3 shows the Image size for DX Image area.

3. Use the Multi selector to select a size and press the OK button to choose the size.

You can also use the QUAL button to set the Image size (and quality):

Figure 3.10 – Choosing an Image size setting with external controls

1. Hold down the QUAL button (figure 3.10, image 1).

2. Rotate the Sub-command dial (top red arrow in figure 3.10, image 2) to change the Image size. Also, rotate the Main command dial to change the Image quality (bottom red arrow in figure 3.10, image 2).

3. Look at the Control panel to see the Image size and Image quality values change. The top red arrow in figure 3.10, image 3, shows the size (L, M, S), and the bottom red arrow shows the quality (RAW, FINE, RAW+FINE, etc.).

4. Release the QUAL button to lock in the settings.

I’m not very interested in using my 24.2 MP camera to capture smaller images. However, there are reasons to shoot at lower megapixel sizes, such as when a smaller-resolution image is all that will ever be needed or if card space is at an absolute premium.

Setting the Image quality to JPEG basic, the Image size to Small, the Image area to DX mode, and the JPEG compression to Size priority allows the camera to capture 10,300 images on an 8 GB card. The images are 2.6 MP in size (1968 × 1312 = 2,582,016 pixels, or about 2.6 MP) and are compressed to the maximum level, but the card can hold a lot of them. If I were to journey completely around the earth and I had only one 8 GB memory card to take with me, I could use these settings to document my trip well because the camera could store more than 10,000 images on one card.

Note: As previously mentioned, Image size applies only to JPEG images. If you see Image size grayed out on your camera Monitor, you have NEF (RAW) format selected.

Settings Recommendation: You’ll get the best images with the Large (24.2 M) Image size. The smaller sizes won’t affect the quality of a small print, but they will seriously limit your ability to enlarge your images. I recommend leaving your camera set to Large unless you have a specific reason to shoot smaller images.

(User’s Manual – Page 89)

Image area is a convenient built-in automatic crop of the FX image to a smaller size. The FX (3:2) area is 36 ×24mm, and the DX (1.5x) area is 24 ×16mm. If you need this particular image area, you will be familiar with the industry-standard DX format. Figure 3.10.4 shows the DX format graphically.

The camera can automatically switch to DX mode when it detects that you have mounted a DX lens, or you can set the camera so it stays in the FX format unless you select DX. You will use Auto DX crop to make that decision.

Here are the results of each of those choices:

• On – If Auto DX crop is set to On, the camera will automatically switch formats when you mount a DX lens.

• Off – Setting Auto DX crop to Off means the camera will ignore the lens you have mounted and stay in FX format; it will usually vignette or leave dark edges on the images you take with most DX lenses.

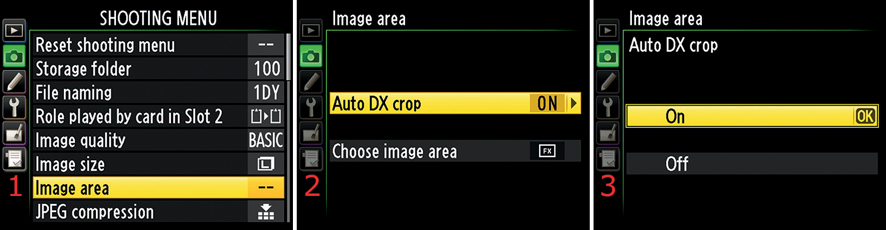

Figure 3.10.1 – Choosing Auto DX crop

Use the following steps to select Auto DX crop:

1. Select Image area from the Shooting Menu and scroll to the right (figure 3.10.1, screen 1).

2. Choose Auto DX crop and scroll to the right (figure 3.10.1, screen 2).

3. Select On or Off (figure 3.10.1, screen 3).

4. Press the OK button to save the setting.

Now, let’s take a look at the two Image area sizes by examining pictures I took in both formats. These two images are of my rebuilt 1940s-era Agfa Isolette III folding rangefinder camera, with its cool new red bellows (120 roll film format).

Figure 3.10.2 – The two Image area formats

I did not vary the camera position so you can see how the change in Image area affects the size (crop) of the subject (figure 3.10.2). Note that the crop of the DX mode drops the resolution of the image from 24.2 MP to 10.3 MP.

The following is a detailed list of specifications for the two available image areas, including sensor format crop (mm), Image size, pixel count, and megapixel (M) rating:

• Large – 7360 ×4912 – 36.2 M

• Medium – 5520 ×3680 – 20.3 M

• Small – 3680 ×2456 – 9.0 M

• Large – 4800 ×3200 – 15.4 M

• Medium – 3600 ×2400 – 8.6 M

• Small – 2400 ×1600 – 3.8 M

Now, let’s see how to select one of these Image area formats for those times when you need to vary the Image area crop.

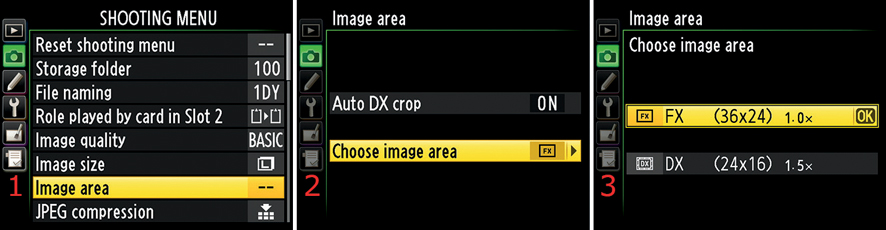

Figure 3.10.3 – Choosing an Image area format

Use the following steps to select one of the Image area formats:

1. Choose Image area from the Shooting Menu and scroll to the right (figure 3.10.3, screen 1).

2. Select Choose image area and scroll to the right (figure 3.10.3, screen 2).

3. Select one of the image area crops. FX is selected in figure 3.10.3, screen 3.

4. Press the OK button to save the Image area setting.

There are two ways the Nikon D610 can show you the boundaries of the DX mode frame in the viewfinder. The first is a simple rectangle boundary frame for the exact size of the DX crop, and the second is by graying out the edges of the frame surrounding the DX crop (figure 3.10.4).

Figure 3.10.4 – DX mode shown in the FX-sized Viewfinder

Figure 3.10.4, screen 1, shows the default behavior of the Viewfinder in DX mode. A rectangular frame shows the DX area crop. Anything outside that frame is not seen in a DX image. It is a true 10.3 MP crop out of the center of the 24.2 MP FX sensor.

Figure 3.10.4, screen 2, shows an alternate way the camera can display the DX crop. You will see this grayed-out area surrounding the DX crop, instead of the rectangular outline, if you have set Custom Setting Menu > a Autofocus > a4 AF point illumination to Off. Of course, that means your AF points will never illuminate, which may be undesirable in some circumstances, such as with low ambient light pictures.

Most people simply leave a4 AF point illumination set to On and remember not to let any of their subject stray outside the DX crop rectangle. That’s the way I do it. I’d rather have my camera’s AF points flash when I press the Shutter-release button halfway so I can find which AF point I am using. However, if you use DX crop often, you may want to use the grayed-out Viewfinder for DX mode shooting.

When you shoot in Live view modes, the Monitor automatically shows the entire FX or DX mode image without any frames or graying.

Note: You can assign a feature called Choose image area to a camera button, such as the Fn or Preview button. Then you can adjust the FX or DX Image area mode on the fly without using the Shooting Menu. We will consider how to make the assignment in the next chapter, Custom Setting Menu, in the sections for Custom settings f2 Assign Fn button and f3 Assign preview button.

Settings Recommendation: Being a nature shooter, I normally leave my camera set to FX, the largest image area. If I need a little extra reach, I may switch the camera to DX mode for convenience, although I could also simply crop the image later in the computer. If you shoot a lot of wildlife or sports and can use a 10.3 MP DX image, you may choose to use DX mode more often to get the extra reach without taking time to crop later.

(User’s Manual – Page 94)

JPEG compression allows you to further fine-tune the compression level of your JPEG images. The JPEG format is always compressed. The Image quality settings for JPEG images include fine, normal, and basic. Each of these settings compress the file size to a certain level.

As discussed previously, a JPEG fine file has a 1:4 compression ratio, JPEG normal has a 1:8 ratio, and JPEG basic has a 1:16 ratio. A JPEG file is smaller than a RAW file.

The size of JPEG files will normally vary when the subject in one image is more complex than the subject in another image. For instance, if you take a picture of a tree with bark and lots of leaves against a bright blue sky, the JPEG compression has a lot more work to do than if you take a picture of a red balloon on a plain white background. All those little details in the picture of the tree cause lots of color contrast changes, so the JPEG file size will naturally be bigger for the complex image. In the balloon image, there is little detail in the balloon and the background, so the JPEG file size will normally be much smaller.

What if you want all your JPEG images to be the same approximate size? Or what if file size doesn’t matter to you and quality is much more important? That’s what the JPEG compression menu allows you to control. Let’s discuss the two settings:

• Size priority – This compression setting is designed to keep all your JPEG files at a certain uniform size. This size will vary according to whether you selected JPEG fine, normal, or basic in the Image quality menu. Image quality controls the regular, everyday compression level of the JPEG file, and Size priority tweaks it even more. How does it work? With Size priority enabled, the camera software has a target file size for all the JPEGs you shoot. Let’s say the target size is 9.5 MB. The D610 will do its best to keep all JPEGs set to that particular file size by altering the level of compression according to content. If a JPEG file has lots of fine detail, it will require more compression than a file with less detail to maintain the same file size. By enabling this function, you are telling the camera that it has permission to throw away however much image data it takes to get each file to the 9.5 MB target. This could lower the quality of a complex landscape image much more than an image of a person standing by a blank wall. Size priority instructs the camera to sacrifice image quality—if necessary—to keep the file size consistent. Use this function only for images that will not be used for fine art purposes. Otherwise your image may not look as good as it could.

• Optimal quality – This setting doesn’t do anything extra to your images; the camera simply uses less compression on complex subjects. In effect, you are telling the camera to vary the file size so the image quality will be good for any subject—complex or plain. Instead of increasing compression to make an image of a complex nature scene fit a certain file size, the camera compresses the image only to the standard compression level based on the Image quality you selected (JPEG fine, normal, or basic) to preserve image quality. Less image data is thrown away, so the image quality is higher. However, the file sizes will vary depending on the complexity of the subject.

Figure 3.11 – Choosing a JPEG compression type

The steps to choose a JPEG compression type are as follows:

1. Select JPEG compression from the Shooting Menu and scroll to the right (figure 3.11, screen 1).

2. Choose Size priority or Optimal quality. Figure 3.11, screen 2, shows Optimal quality as the selected compression type.

3. Press the OK button.

Settings Recommendation: I normally use Optimal quality when I shoot JPEGs because the JPEG format uses lossy compression, and I don’t want the potentially heavier compression of Size priority to lower the image quality even more. The only time I use Size priority is when I’m shooting what I call “party pics.” When I’m at a party shooting snapshots of friends having a good time, I’m not creating fine art and will never make an enlargement greater than 8 ×10 inches (20 ×25 cm), so I don’t worry about extra compression. In fact, I might welcome it to avoid storing larger-than-needed images on my computer hard drive.

Using Size priority lets the camera use maximum compression to maintain the JPEG compression ratios. Your images may not have those precise compression ratios if you use Optimal quality—especially with complex, detailed subjects.

(User’s Manual – Page 94)

NEF (RAW) recording is composed of two menu choices: Type and NEF (RAW) bit depth. Type is concerned with image compression, and NEF (RAW) bit depth deals with color quality. We’ll look at both of these choices and see how your photography can benefit from them.

In previous sections we discussed how JPEG files have different levels of compression that vary the size of a finished image file. NEF (RAW) also has compression choices, though not as many. The nice thing about the RAW compression methods is they don’t throw away massive amounts of image data like JPEG compression does. NEF (RAW) is not considered a lossy format because the file stays complete, with virtually all of the image data your camera captured.

One of the NEF (RAW) compression methods, called Compressed, is very slightly lossy. The other, Lossless compressed, keeps all the image data intact. Let’s discuss how each of the available compression methods works.

Although there are two NEF (RAW) formats available, you see a single NEF (RAW) selection on the Image quality menu. After you select NEF (RAW), you need to use Shooting Menu > NEF (RAW) recording > Type to select one of the two NEF (RAW) compression types:

• NEF (RAW) Lossless compressed (20–40 percent file size reduction) – The factory default for the NEF (RAW) format is Lossless compressed. According to Nikon, this compression will not affect image quality because it’s a reversible compression algorithm. Since Lossless compressed shrinks the stored file size by 20 to 40 percent—with no image data loss—it’s my favorite compression method. It works somewhat like a ZIP file on your computer; it compresses the file but allows you to use it later with all the data still available.

• NEF (RAW) Compressed (35–55 percent file size reduction) – Before the newest generation of cameras, including the D610, the Compressed mode was known as visually lossless. The image is compressed and the file size is reduced by 35 to 55 percent, depending on the amount of detail in the image. There is a small amount of data loss involved in this compression method. Most people can’t see the loss since it doesn’t affect the image visually. I’ve never seen any loss in my images with the Compressed mode. However, I’ve read that some people notice slightly less highlight detail. Nikon says the Compressed mode uses nonreversible compression, with “almost no effect on image quality.” However, after you’ve taken an image using this mode, any small amount of data loss is permanent. If this concerns you, then use the Lossless compressed method. It won’t compress the image quite as much (20 to 40 percent instead of 35 to 55 percent), but it is guaranteed by Nikon to be a reversible compression that does not affect the image. Evidently, most of the small compression loss occurs in the brightest parts (highlights) of the image, which contain most of the image data.

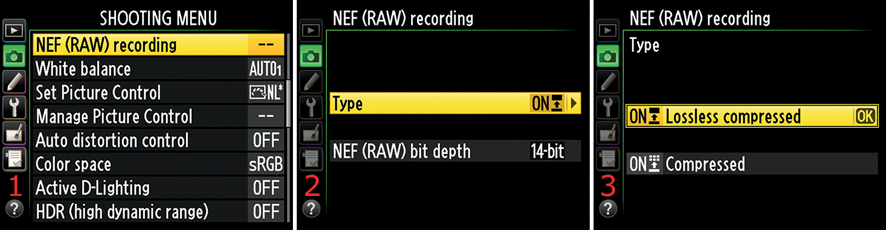

Figure 3.12 – Choosing a NEF (RAW) recording compression type

The steps to select a NEF (RAW) recording compression Type are as follows:

1. Select NEF (RAW) recording from the Shooting Menu and scroll to the right (figure 3.12, screen 1).

2. Choose Type and scroll to the right (figure 3.12, screen 2).

3. Select a compression method from the Type menu (figure 3.12, screen 3). I chose Lossless compressed.

4. Press the OK button to save your selection.

An image with a large area of blank space, such as an expanse of sky, will compress a lot more efficiently than an image of, for example, a forest with lots of detail. The camera displays a certain amount of image storage capacity in NEF (RAW) modes—about 151 images on an 8 GB card.

In the two NEF (RAW) compressed modes, the D610 does not decrease the image capacity counter by one for each picture taken. Instead, it decreases the counter approximately every two shots, depending on how well it compressed the images. When the card is full, it might contain nearly twice as many images as the camera initially reported it could hold. Your D610 deliberately underreports storage capacity when you are shooting in either of the NEF (RAW) compressed modes because it can’t anticipate how well the compression will work on each image.

Settings Recommendation: I’m concerned about maximum quality along with good storage capacity, so I shoot in Lossless compressed mode all the time. It makes the most sense to me since it produces a file size close to half the size of a normal uncompressed RAW file (if you could create one with the D610, which you can’t). More expensive Nikon cameras can create uncompressed RAW files, although there’s no point when a Lossless compressed file retains all data and is stored on your computer hard drive at close to half the size.

I haven’t used Compressed mode much since Lossless compressed became available in Nikon cameras a few years ago. Even though I can’t see any image quality loss, it bothers me that it’s there, if only slightly. The extra 10 or 15 percent compression is not worth the potential small data loss to me. If I were running out of card space but wanted to keep shooting RAW, I might consider changing to Compressed temporarily. Otherwise it’s Lossless compressed for me!

NEF (RAW) bit depth is a special feature for those of us concerned with capturing the best color in our images. The D610 has three color channels, one for red, another for green, and the last one for blue (RGB). The camera combines those color channels to form all the colors you see in your images. Let’s talk about how bit depth, or the number of colors per channel, can make your pictures even better.

With the D610, you can select the bit depth stored in an image. More bit depth equals better color gradations. An image with 12 bits contains 4,096 colors per RGB channel, and an image with 14 bits contains 16,385 colors per RGB channel. In lesser DSLR cameras, the color information is limited to 12 bits. If you do not fully understand what this means, take a look at the Channel and Bit Depth Tutorial following this section.

The D610 has the following two bit depths available: 12 bit (4,096 colors per channel) and 14 bit (16,385 colors per channel).

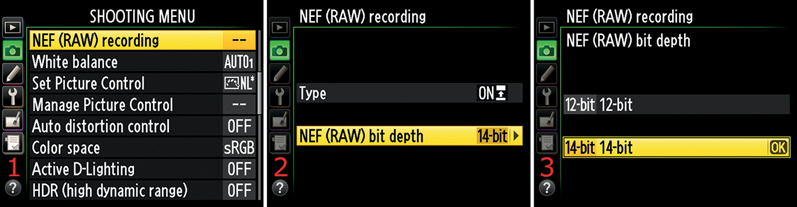

Figure 3.13 – Choosing a NEF (RAW) bit depth

The steps to choose a NEF (RAW) bit depth are as follows:

1. Select NEF (RAW) recording from the Shooting Menu and scroll to the right (figure 3.13, screen 1).

2. Select NEF (RAW) bit depth and scroll to the right (figure 3.13, screen 2).

3. Select 12-bit or 14-bit from the NEF (RAW) bit depth menu (figure 3.13, screen 3).

4. Press the OK button to save your selection.

Settings Recommendation: Which bit depth setting is best? I always use 14 bit because I want all the color my camera can capture for the best possible pictures. If you read my bit depth tutorial in the next subsection, you’ll understand why I feel that way. My style of shooting is nature oriented, so I am concerned with capturing every last drop of color I can.

There is one small disadvantage to using the 14-bit mode. Your file sizes will be 1.3 times larger than they would have been in 12-bit mode. There is a lot more color information being stored, after all.

What does all this talk about bits mean? Why would I set my camera to use to 14-bit depth instead of 12-bit depth? This short tutorial explains bit depth and how it affects color storage in an image.

An image from your camera is an RGB image, where each of the three colors—red, green, and blue—have separate channels. If you’re shooting in 12-bit mode, your camera will record up to 4,096 colors for each channel, so there will be up to 4,096 different reds, 4,096 different greens, and 4,096 different blues. Lots of color! In fact, almost 69 billion colors (4,096 × 4,096 × 4,096). If you set your camera to 14-bit mode, the camera can store 16,384 different colors in each channel. Wow! That’s quite a lot more color—almost 4.4 trillion shades (16,384 × 16,384 × 16,384).

Is that important? Well, it can be, since the more color information you have, the better the color in the image—if it has a lot of color. I always use the 14-bit mode. That allows for smoother color changes when a large range of color is in the image. I like that!

Of course, if you save your image as an 8-bit JPEG or TIFF, most of those colors are compressed, or thrown away. Shooting a JPEG image in-camera (as opposed to a RAW image) means that the camera converts the image in a 12- or 14-bit RGB file to an 8-bit file. An 8-bit image file can hold 256 different colors per RGB channel—more than 16 million colors (256 × 256 × 256).

There’s a big difference between the number of colors a camera captures in a RAW file and the number captured in a JPEG file (16 million versus 4.4 trillion). That’s why I always shoot in RAW; later I can make full use of all those extra colors—if the subject contains that many shades—to create a different look for the same image.

If you shoot in RAW and later save your image as a 16-bit TIFF file, you can store all the colors you originally captured. A 16-bit file can contain 65,536 different colors in each of the RGB channels, which is significantly more than the camera actually captures.

Many people save their files as 16-bit TIFFs when they post-process RAW files, especially if they are worried about the long-term viability of the NEF (RAW) format. TIFF gives us a known and safe industry-standard format that will fully contain all image color information from a RAW file.

It’s important that you learn to use your camera’s histogram so you can examine the various RGB channels at a glance.

We’ll discuss the histogram in an upcoming chapter titled Metering, Exposure Modes, and Histogram. In the meantime, please look at figure 3.14, which shows the histogram screen on your camera and its RGB channels.

Figure 3.14 – RGB histogram screen

We talked about this screen in the chapter titled Playback Menu. However, I want to tie this in here to help you understand channels better. The histogram displays the amount and brightness of color for each of the RGB channels.

In figure 3.14 you can see four small histograms on the right side of the screen. The bottom three histograms represent the red, green, and blue color channels, as can easily be seen.

The white histogram on top is not an additional channel. It is called a luminance histogram, and it represents a combined, weighted histogram for the three color channels (green 59 percent, red 30 percent, and blue 11 percent). It is also known as a brightness histogram. In reality, even though all the color channels influence the luminance histogram, much of its information comes from the green channel. Notice that the luminance histogram and green channel histogram are very similar.

In digital photography we must use new technology and learn lots of new terms and acronyms. However, by investing a little time to understand these tools, we’ll become better digital photographers.

(User’s Manual – Page 115)

White balance is designed to let you capture accurate colors in each of your camera’s RGB color channels. Your images can reflect realistic colors if you understand how to use the White balance settings. This is an important thing to learn about digital photography. If you don’t understand how White balance works, you’ll have a hard time when you want consistent color across a number of images.

In this section we will look at White balance briefly and learn how to select the various White balance settings. This is such an important concept to understand that an entire chapter—titled White Balance—is devoted to this subject. Please read that chapter very carefully. It is important that you learn to control the White balance settings thoroughly. A lot of what you’ll do in computer post-processing requires a good understanding of White balance control.

Many people leave their cameras set to Auto White balance. This works fine most of the time because the camera is quite capable of rendering accurate color. However, it’s hard to get exactly the same White balance in each consecutive picture when you are using Auto mode. The camera has to make a new White balance decision for each picture in Auto. This can cause the White balance to vary from picture to picture.

For many of us this isn’t a problem. However, if you are shooting in a studio for a product shot, I’m sure your client will want the pictures to be the same color as the product and not vary among frames. White balance lets you control that carefully, when needed.

Figure 3.15 – Setting White balance to Auto1 – Normal

The steps to select a White balance setting are as follows:

1. Select White balance from the Shooting Menu and scroll to the right (figure 3.15, screen 1).

2. Choose a White balance type, such as Auto or Flash, from the menu and scroll to the right (figure 3.15, screen 2).

3. If you choose Auto, Fluorescent, Choose color temp., or Preset manual you will need to select from an intermediate screen, shown in figure 3.15, screen 3. Auto presents two settings: Auto1 – Normal and Auto2 – Keep warm lighting colors. Fluorescent presents seven different types of fluorescent lighting. Choose color temp. allows you to select a color temperature manually from a range of 2500 K (cool) to 10000 K (warm). Preset manual (PRE) shows the stored White balance memory locations d-1 through d-4 and allows you to choose one of them. If this seems a bit overwhelming, just choose Auto1 – Normal for now. The chapter titled White Balance will explain how to use all these settings.

4. As shown in figure 3.15, screen 4, you’ll now arrive at the White balance fine-tuning screen. You can make an adjustment to how you want this White balance to record color by introducing a color bias toward green, yellow, blue, or magenta. You do this by moving the little black square in the middle of the color box toward the edges of the box in any direction. If you make a mistake, simply move the black square to the middle of the color box. Most people do not change this setting.

5. After you have finished adjusting (or not adjusting) the colors, press the OK button to save your setting. Most people press the OK button as soon as they see the fine-tuning screen so they don’t change the default settings for that particular White balance.

You’ll also find it convenient to change the White balance settings by using external camera controls:

Figure 3.16 – Setting White balance with external controls

1. Hold down the WB button, which shares functionality with the Help/protect button (figure 3.16, image 1).

2. Turn the Main command dial (figure 3.16, image 2) as you watch the WB icons change on the Control panel (figure 3.16, image 3).

3. Release the WB button to lock in your choice.

Settings Recommendation: Until you’ve read the chapter titled White Balance, I suggest that you leave the camera’s White balance set to Auto1 – Normal. However, please do take the time to understand this setting by reading the dedicated chapter carefully. Understanding White balance is especially important if you plan to shoot JPEGs regularly.

(User’s Manual – Page 129)

Set Picture Control allows you to choose a Picture Control for a shooting session. Nikon’s Picture Control system lets you control how your image appears in several ways. Each control has a specific effect on the appearance of the image. If you ever shoot film, you know that there are distinct looks to each film type. No two films produce color that looks the same.

In today’s digital photography world, Picture Controls give you the ability to impart a specific look to your images. You can use Picture Controls as they are provided from the factory, or you can fine-tune Sharpening, Contrast, Brightness, Saturation, and Hue.

We’ll discuss how to fine-tune a Nikon Picture Control later in this section. In the next section we’ll discuss how to save a modified Picture Control under your own Custom Picture Control name. You can create up to nine Custom Picture Controls.

I’ll refer to Picture Controls included in the camera as Nikon Picture Controls since Nikon does too. You may also see them called Original Picture Controls in some Nikon literature. If you modify and save a Nikon Picture Control under a new name, it becomes a Custom Picture Control. I’ll also use the generic name of Picture Control when I refer to any of them.

The cool thing about Picture Controls is that they are shareable. If you tweak a Nikon Picture Control and save it under a name of your choice, you can then share it with others. Compatible cameras, software, and other devices can use these controls to maintain the look you want from the time you press the Shutter-release button until you print the picture with a program like Nikon Capture NX2.

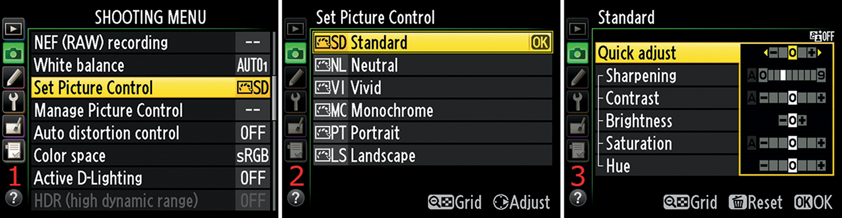

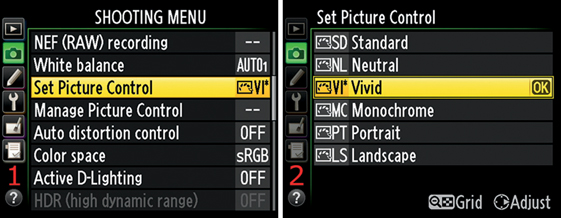

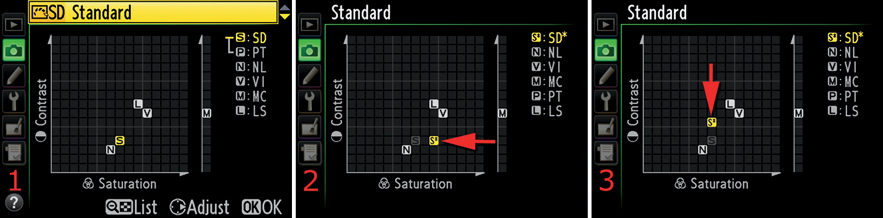

Figure 3.17 – Choosing a Picture Control with the Shooting Menu

The steps to choose a Picture Control, using the camera’s Shooting Menu, are as follows:

1. Select Set Picture Control from the Shooting Menu and scroll to the right (figure 3.17, screen 1).

2. Choose one of the Nikon Picture Controls from the Set Picture Control screen (figure 3.17, screen 2).

3. At this point, you can simply press the OK button and the control you’ve chosen will be available for immediate use. It will show up as a two-letter name in the Shooting Menu next to Set Picture Control. You can see this in figure 3.17, screen 1, where SD is displayed to the right of Set Picture Control.

4. You can also modify the currently highlighted control by scrolling to the right (figure 3.17, screen 3). This will bring you to the fine-tuning screen. You can adjust the Sharpening, Contrast, Brightness, Saturation, and Hue settings by scrolling up or down to select a line and then scrolling right or left (-/+) to change the value of that line item. This is entirely optional. When you are finished, press the OK button.

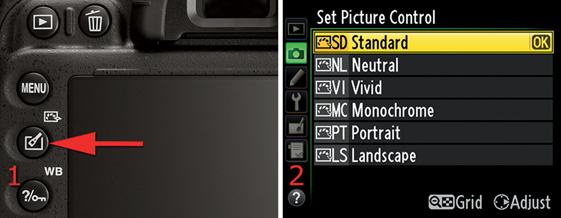

You can also select a Picture Control by using a combination of the external Picture Control/Retouch button and the Set Picture Control menu that pops up when you press it (figure 3.17.1).

Figure 3.17.1 – Choosing a Picture Control with the Picture Control/Retouch button

Use the following steps to choose a Picture Control with the more direct external method:

1. Press the Picture Control/Retouch button (figure 3.17.1, image 1).

2. Select your preference from the Set Picture Control menu with the Multi selector (figure 3.17.1, screen 2).

3. Press the OK button to lock in your choice.

Either of these two methods work well. The more direct external method of using the Picture Control/Retouch button is preferred by most D610 owners.

What if you want to modify a Picture Control by changing its sharpness, contrast, brightness, saturation, or hue? Figure 3.17, screen 3, shows the settings to change any of those values.

If you do choose to modify a control, it is not yet a Custom Picture Control because you haven’t saved it under a new name. Instead, it’s merely a modified Nikon Picture Control. We’ll discuss how to name and save your own Custom Picture Controls in the upcoming section called Manage Picture Control.

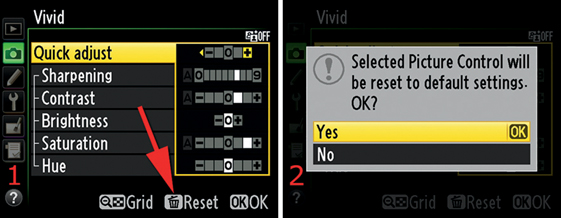

Screens 1 and 2 of figure 3.18 show an asterisk after the Vivid Picture Control (VI* – Vivid). This asterisk appears after you have made a modification to any of the Picture Control’s inner settings, such as Sharpening or Contrast. The asterisk will go away if you set the control back to its factory default configuration.

Figure 3.18 – The Vivid Picture Control has been modified

Note: You can reset a Picture Control by pressing the Delete button when you are in the Quick adjust screen shown in figure 3.17, screen 3.

Now, let’s take a closer look at the Picture Control system. As shown in figure 3.17, screen 2, and figure 3.17.1, screen 2, there is a series of Picture Control selections that modify how your D610 captures an image:

• SD – Standard

• NL – Neutral

• VI – Vivid

• MC – Monochrome

• PT – Portrait

• LS – Landscape

Each of these settings has a different and variable combination of the following settings:

• Sharpening

• Contrast

• Brightness

• Saturation

• Hue

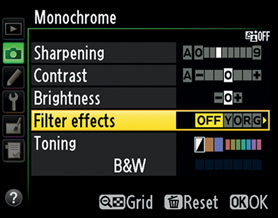

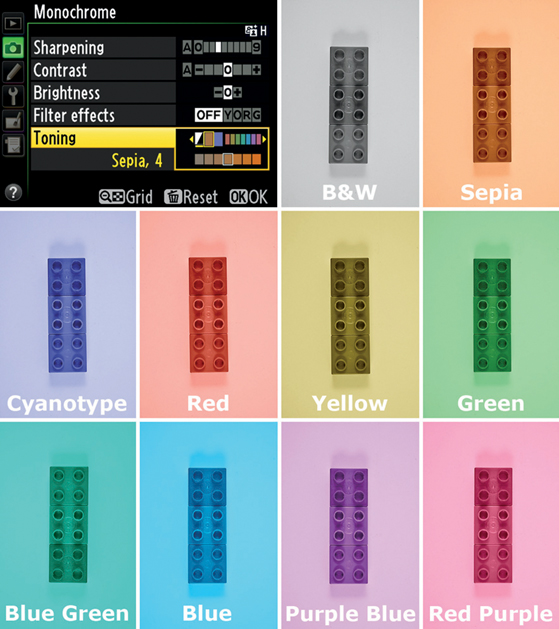

• Filter effects (MC only)

• Toning (MC only)

You can select one of the controls and leave the settings at the factory defaults, or you can modify the settings and completely change how the D610 captures the image (figure 3.17, screen 3). If you shoot in one of the NEF (RAW) modes, the D610 does not apply these settings to the image permanently; it stores them with the image so you can change them during post-processing in your computer. If you shoot JPEG, the camera immediately and permanently applies the settings you’ve chosen. Let’s examine each of the Picture Controls.

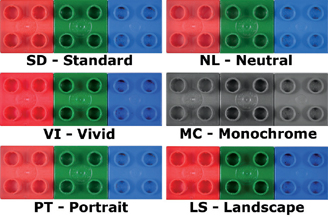

Figure 3.19 provides a look at the differences in color saturation and shadow with the various controls. Due to limitations in printing, it may be hard to see the variations. Saturation and Contrast depth increases within these Picture Control choices, in this order: NL (low), SD (medium), VI (high).

Figure 3.19 – Red, green, and blue with all six Picture Controls

The following is an overview of what Nikon says about Picture Controls and what you will see in figure 3.19 with the various controls.

• SD, or Standard, is Nikon’s recommendation for getting “balanced” results. They recommend SD for most general situations. Use this Picture Control if you want a balanced image and don’t want to post-process it. The control has what Nikon calls “standard image processing.” It provides what I would call medium saturation, with darker shadows to add contrast. If I were shooting JPEG images in a studio or during an event, I would seriously consider using the SD control. I would compare this setting to Fuji Provia or Kodak Kodachrome 64 slide films.