Feminism and Femininity |

2 |

I turned thirteen in 1962. Before I graduated from middle school, three books hit the best-seller lists, each offering a completely different, competing view of what sort of woman I should try to be. Let the authors speak for themselves:

When a man thinks of a married woman, no matter how lovely she is, he must inevitably picture her greeting her husband at the door with a martini or warmer welcome, fixing little children’s lunches or scrubbing them down because they’ve fallen into a mudhole. She is somebody else’s wife and somebody else’s mother.

When a man thinks of a single woman, he pictures her alone in her apartment, smooth legs sheathed in pink silk Capri pants, lying tantalizingly among dozens of satin cushions, trying to read but not very successfully, for he is in that room—filling her thoughts, her dreams, her life.

—HELEN GURLEY BROWN, SEX AND THE SINGLE GIRL, 1962

The problem lay buried, unspoken, for many years in the minds of American women. It was a strange stirring, a sense of dissatisfaction, a yearning that women suffered in the middle of the twentieth century in the United States. Each suburban wife struggled with it alone. As she made the beds, shopped for groceries, matched slipcover material, ate peanut butter sandwiches with her children, she ferried Cub Scouts and Brownies, lay beside her husband at night—she was afraid to even ask herself the silent question—“is this all?”

—BETTY FRIEDAN, THE FEMININE MYSTIQUE, 1963

There are, of course, many women who have achieved a high level of happiness, but in many cases it is not the happiness of which they once dreamed, and it falls short of their goals. They feel a need for a richer, fuller life. They, too, need light and understanding.

—HELEN B. ANDELIN, FASCINATING WOMANHOOD, 1963

I hasten to say that although I didn’t read any of these books at the time, the ideas each author advocated swirled around me throughout my high school and college years. (And they are all still in print fifty years later, which is certainly telling.) Which women should I be? Helen Gurley Brown’s independent, sexy, young, single girl? Betty Friedan’s liberated woman with a career and perhaps an equally liberated husband? Or Helen Andelin’s domestic goddess, realizing her power by cultivating her femininity? When faced with a multiple-choice test, I turned it into an essay exam. Like many women of my generation, I tried a bit of each.

American women’s fashions in the 1960s and ’70s—and today—were the battlefield for these competing visions of the feminine. In this chapter I examine two main themes that emerged during this period in women’s clothing. The first is the desire for an independent existence that is equal in political and social status to men; the second is the very real drive to be sexual beings. Yet these were not separate strands at all. As we’ll see, unisex or androgynous dressing, while intended to level the playing field between men and women, was often perceived as sexually attractive as well, and sexually attractive clothing can be powerful. It is the very tension between these two impulses that helped drive fashion change during this period and that made it so very complicated.

Each of the three works that open this chapter had a different impact with a different audience. The Feminine Mystique is credited with launching second-wave feminism and routinely appears on lists of significant books for required reading. Sex and the Single Girl, in contrast, is listed on Amazon.com as a “cult classic,” and amateur reviewers on the site disagree whether it is a humorous period piece or the best advice book ever written. It not only helped Brown rebrand Cosmopolitan from housewifely to collegiate when she took over as editor of the magazine in 1965, but it also inspired new popular culture heroines, from a film version of the book, starring Natalie Wood, to the fashionista girlfriends of Sex and the City. All three books have sold millions of copies. The Feminine Mystique could boast three million copies sold by 2000 (in just less than forty years)—no small feat for a serious nonfiction title—but Sex and the Single Girl claimed two million sold in three weeks. Compared to both of these, Fascinating Womanhood was more of an underground success. Self-published in 1963, it sold four hundred thousand copies before Random House bought it and republished it in 1965. It really caught on as Andelin developed courses and teacher training that fed the conservative antifeminist movement in the 1970s. Total sales today have reached over two million.

Of these three books, The Feminine Mystique offers the least amount of fashion commentary or advice. Friedan was critical of the consumerist role of suburban housewives and, by extension, the preoccupation with fashionable clothing promoted by women’s magazines. She did, however, convey a sense of fashion being a frivolous feminine pursuit as opposed to the more serious pursuits of political power and legal careers.

In contrast, both Fascinating Womanhood and Sex and the Single Girl provide fairly specific advice on clothing choices, although Helen Gurley Brown goes into much greater detail; she devotes an entire chapter to clothing as opposed to just a few pages in Andelin’s book. Brown’s imagined reader was a young woman with lots of ambition but not a whole lot of money, so her advice focused on getting the most attractive looks for the least amount of money. She also argued that young women should please themselves with their clothing, not men, since if they appear confident and well put together, men will find them attractive regardless of the style. To round out the image found in Sex and the Single Girl, it helps to understand that the chapter preceding the one on clothes includes quite a bit of diet and exercise advice, and the chapter following dispenses makeup and hairstyling information.

In Fascinating Woman, on the other hand, a woman’s appearance is considered the reader’s first step toward regaining lost femininity. To look feminine, women must avoid any materials or styles that men wear unless they can be feminized through color, trim, or accessories. The main strategy is to emphasize the differences between women and men. Both authors agree that overly sexy clothing, or at least obviously sexy clothing, is undesirable. For Helen Gurley Brown, too-revealing clothing is low-class and attracts the wrong sort of man; for Helen Andelin, sexy clothing violates one of the most important rules of true femininity: a woman should be modest.

Imagine that the millions of readers of these three books constitute three categories of female consumers. Then consider the larger reality that these categories—feminists, “Cosmo girls,” and domestic goddesses—were neither exhaustive nor mutually exclusive. There were women who were “none of the above.” Consider, for example, the young lesbian who wants to succeed in her clerical job with a big firm and also dreams of love and romance with a woman. Then there were the countless women like me, whose heads spun with the options and possibilities and wanted a bit of each (or, in the cliché of the 1980s, “to have it all”).

Women had started wearing pants before the 1960s. First-wave feminists had challenged men’s exclusive right to trousers in the nineteenth century, winning small but significant victories: overalls and rompers for children’s play clothes and bloomers and knickers for women’s active sportswear. By the early 1960s trousers in many forms—jeans, capris, and shorts—were acceptable leisure styles for American women, particularly the young. Between 1965 and 1975 this acceptance pushed past existing boundaries into the workplace, the schoolroom, and even formal occasions, to the point that trousers were no longer considered masculine, but, rather, neutral garments. Although this change represented a fundamental shift in public attitudes and perceptions, it ultimately did not result in neutral clothing styles. By the late 1970s women’s trousers were acquiring feminine details and fit more closely to the hips and thighs, accentuating the sex of the wearer rather than creating a neutral effect. Once pants were no longer seen as inherently masculine, they simply became another vehicle for displaying the female body.

In medieval Europe trousers were underwear; men wore these tight-fitting leg coverings under their robes, and women did not wear them at all. Between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries, shorter and shorter robes and doublets revealed the legs, and eventually the buttocks, up to the waist, and men’s lower garments became important fashion items in their own right. Loose or skin-tight, knee-length or longer, trousers distinguished men from women and men from boys, who wore dresses from infancy until old enough to be “breeched” at six or seven years. Early advocates of equal rights for women took note of the relative freedom of men’s and women’s clothing and argued for dress reform to erase the restrictions of women’s fashionable dress. Corsets, layers of petticoats, and wide, sweeping skirts were all indicted as markers of women’s dependent and subservient status. Activists including Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Amelia Bloomer advocated adoption of simplified dress consisting of a knee-length dress over a pair of wide trousers based on those worn by women in the Middle East. They called it the “American Costume,” to emphasize their goal of emancipating women from the dictates of foreign designers, but it was popularly known as the Bloomer dress. It didn’t last long: it was introduced in 1851 and abandoned by Amelia Bloomer herself in 1859 when lightweight cage crinolines replaced heavy layers of petticoats as skirt supports. But the seeds had been sown; there is ample evidence that women continued to defy convention and put on trousers, whether for practical or political reasons. Early photography provides a wealth of images of women in pants as workers, soldiers, performers, and just for a bit of cross-dressing fun.1 In the struggle for women’s rights, wearing trousers was considered a subversive, even disruptive act, and cartoonists often depicted a post-suffrage future of mannish, trousered wives and hen-pecked husbands.

By the 1950s a woman in pants was no longer a cause for alarm or an object of ridicule, as long as she observed the new rules. Slacks, shorts, capris, pedal pushers, and other trouser variants were for leisure, not for school, office, or church. Women’s Wear Daily publisher John Fairchild declared in his 1965 book, The Fashionable Savages, that pants for women were fine “at home, [for] winter sports and the country, not in city streets,” a sentiment echoed by most designers and retailers.2 In a setting where either slacks or a dress could be worn, it was more “ladylike” to wear a skirt, and skirts were clearly preferred for grown women. A bowling manual for women in 1964 suggested “culottes, skirts and blouses, sports dresses and even slacks are suitable for lane-wear,” but only one adult woman in the entire book is shown in slacks. Only the girls are wearing slacks or shorts.3 Menswear tailoring was rare, images of Katharine Hepburn notwithstanding; most pants for women and girls were cut and styled differently from men’s. They were slimmer, with tapered legs and side or back zippers and few or no pockets. Panty girdles worn beneath slacks ensured the control and smooth line expected under all women’s clothing, even for active sports such as tennis.

But by 1965 the door had already been opened by some Paris designers, especially André Courrèges, whose August 1, 1964, show featured rock music and “pants, pants, pants,”4 while the venerable but still iconoclastic Coco Chanel offered flowing pants for home entertaining. Within a few years most designers were showing pants in some form, and pantsuits were rapidly gaining in acceptability. Some schools and workplaces were more resistant than others; nurses in Los Angeles won the right to wear tunics and pants instead of dresses in 1973, and other hospitals followed suit fairly quickly, since pants were clearly more practical than skirts. Banks and fine restaurants held out against pantsuits until the late 1970s. Jeans, as a subcategory of pants especially associated with leisure, were a special case for both men and women, so I discuss them separately when I get to unisex styles.

If unisex and the trend away from formality helped launch the fashion for pants, the surprise accelerant was controversy over skirt lengths. Ever since the introduction of the first miniskirts—which just grazed the knee, a length that hardly seems shocking today—women had faced some serious challenges. Some were practical: according to etiquette, bare legs were déclassé. Skirts called for stockings or, in the case of casual styles or school clothes, tights or knee socks. Tall girls quickly learned that the shorter the skirt, the more it was likely to reveal the gap between stocking top and garters. Tights and pantyhose solved that problem, although at first they were at least twice the cost of regular hosiery. (Never mind the fact that if you were above average height, tights and pantyhose were never long enough.) Tired of the uncertainty generated by pants and miniskirt controversies, the French fashion industry conspired to introduce mid-calf-length (midi) skirts in January 1970, in an attempt to force “wardrobe-killing change,” as Christian Dior had done with his 1947 New Look, which had rendered square shoulders and A-line skirts obsolete in a single season, replacing them with voluminous styles with a Victorian-revival sensibility. Women reacted angrily, interpreting the move as a reactionary attempt to shut down youth culture or to boss women around. For manufacturers and retailers the uncertainty over skirt lengths posed nothing but confusion; they responded by stocking more pants.5 Amid all of this controversy, many women began to see pantsuits as more tasteful, flattering, and modest than either minis or midis. Restrictions on pants evaporated in schools and workplaces across the county; in suburban Detroit the dress code for teachers was changed to permit pantsuits.6

There was some resistance from more conservative women, but even in those quarters slacks were more acceptable if they were feminine. Helen Andelin thought pants had their place (“sports, outings and mountain climbing”) but when worn in other settings they should be distinguished from men’s clothing in some way—color, trim, or accessories. Women who chose mannish clothing for activities such as yard work, she warned, would find themselves treated like “one of the boys,” which would upset the natural male-female relationship.

Perhaps the oddest source of anti-pants opinion was physician Robert Bradley, author of the popular book Husband-Coached Childbirth:

I strongly feel that the current rash of vaginal infections is related to women dressing in men’s-style clothing. I’m an old square who thinks women look graceful and feminine in long skirts with lace and frills to accentuate their femininity. Pioneer women wore long skirts with no underclothes—at least for working—and had far fewer bladder infections than modern women who wear slacks, especially tight, rigid denims, and panty hose. In addition, the exercises of squatting and tailor sitting can be performed so much more easily in a large, loose skirt than in tight-fitting slacks.7

Later studies found trousers innocent on all charges; instead the major culprits were nylon panties and pantyhose.8

Youthquake fashion was about more than style. It established a new standard of beauty: young, slender, and unabashedly sexy. Fashion models had been slender since the 1920s, but they had exuded a cool, mature elegance that matched the sophisticated environment of most haute couture salons. In the mid-1960s young designers such as André Courrèges and Mary Quant challenged this staid image, presenting their fashions on very young models—teenagers or women who looked like teenagers—who hopped or danced down the runway to loud rock music. As women quickly discovered, these new looks went beyond superficial style changes. There were also invisible shifts in sizing and basic pattern design that made a minidress not only look better on a young, slim body but fit better as well. If you were a fashion-conscious woman between 1964 and 1966, you might have wondered if you were gaining weight, but it wasn’t you that changed.

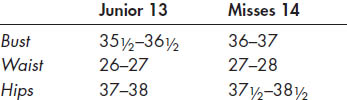

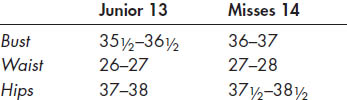

Women’s clothing sizes are not now, and never have been, standardized in the United States, though not for lack of trying. There was an effort in the 1940s and ’50s to develop a statistics-based sizing system that would be adopted by all manufacturers, but, as any woman who buys her own clothes knows, a size 10 from one manufacturer is not a size 10 from another (not to mention companies like Chico’s that have invented their own sizing systems). Catalog retailers and sewing pattern manufacturers were the most transparent in their sizing systems, in order to avoid costly returns and exchanges. The sizing charts from the Sears catalogs in 1964 and 1966 reveal some interesting changes in size categories and measurements. Women’s fashions were organized in three main sections: Junior (odd numbers), Misses (even numbers, usually up to 18 or 20), Women’s (even sizes above the Misses range), and Half Sizes (even numbers with a 1/2 added—for example, 141/2). These were distinct proportions as well as measurements. Size chart listings for a Junior 13 and a Misses 14 in the Sears spring 1966 catalog would have the following measurements:

An observant regular Sears customer in the lower end of the Junior or Misses size ranges might think she had gone up a size since her last purchase, but that was all. The 1966 waist measurements for both size ranges were slightly smaller in proportion to bust and hip, and the Junior styles included shorter skirts; lower, “hip-hugging” waistlines; and more trousers and pantsuits. Because the Junior sizes topped out at about a 38–39-inch bust, women who were larger had to shop in the Misses department, forgoing the hottest trends. This represented a significant shift in the center of gravity in the fashion world, where the teenage market had once been a small, specialized segment.

This shift was not limited to mass-market producers. In 1965 Vogue reported that the basic master patterns (called “slopers”) for the trendiest designers had also changed.9 Not only was “the look” slimly androgynous, but so was the body for which it was designed. The new ideal body had a small, high, wide-set bosom and slender, almost preadolescent hips. Accordingly, the revised patterns featured smaller, higher-cut armholes and higher bustlines. Sleeves were slimmer; pants and skirts were tighter at the hip. None of these changes would have shown in the size charts, but would be noticed in the dressing-room mirror. Short skirts; sleeveless dresses; and tight, hip-hugger pants demanded toned arms, knees, and legs. The author of the Vogue article offered helpful exercise advice to help readers achieve the required effect.10 Bicep curls and leg lifts wouldn’t help the girl with an hourglass figure, of course, or indeed anyone who wasn’t stick-thin. Designer Ruben Torres, predicting jumpsuits for the twenty-first century, declared that they were “for lean, sleek bodies.” What about women who didn’t measure up? the interviewer asked. Torres’s answer was, “Plastic surgery and, for those too old, some veiling, draped at the vital part.”11 It strikes me that if gender ambiguity was the object, unisex fashions were most effective on androgynous bodies. For adults, androgynous bodies come in essentially two varieties: skinny and fat. Skinny men and women could carry off the tiniest unisex styles—hip-hugger pants, for example—because our culture is comfortable with exposed slender bodies. Fat bodies—male and female—were excluded or hidden.

When Junior sizes had been intended for high school girls, their sexiness had been downplayed. The desired effect was fresh and maidenly: the chaste ingénue, not Lolita. But as the size range became more about style than age, the clothing became more revealing and the advertising poses more provocative, even in the pages of the Sears catalog. Women in their late teens and early twenties in the late 1960s were on the front lines of the sexual revolution, with some fairly consequential decisions to make about their lives and bodies. For starters there was the paradox of being encouraged to embrace your sexuality while not being a sex object. The Pill made sex without the fear of pregnancy a reality, but it did not erase the double standard. Intercourse before marriage, or even promiscuity, was judged more harshly for women than men, and wearing clothing that expressed one’s identity as a sexual being could be risky.

Another quandary was the contradiction between second-wave feminist ideology that beauty culture was an artificial distraction that limited women from achieving their full potential and the alternative view, found in both Cosmopolitan and Fascinating Womanhood, that fashion and cosmetics were valuable tools for a woman to get what she wanted. Was it better to “go natural” or embrace commercial enhancements? Didn’t that depend on your natural body and the extent to which it fit the ideal? What about women over thirty? Young mothers in their early twenties? Society women “of a certain age” who were used to dressing well and following trends? Marylin Bender of the New York Times detected this bias toward youth quite early, in 1964: “old maxims to the effect that life begins at 40 and elegance at 30 don’t hold true in fashion any more. The latest news from the Paris couture showings confirms the fact that it is no longer possible to age gracefully and still be in high style.”12 The new mod styles, with their skimpy cuts and juvenile attitude, were just for the young, and older women followed them at their peril. The miniskirt was especially problematic, as it moved from just above the knee to a few inches below the crotch. Women who a few years earlier would have considered trousers “unladylike” found tailored pantsuits a reasonable alternative to dresses in unfashionable lengths or trendy dresses that made them look foolish.

At the other end of the age spectrum were young teens or preteens. Standard sizing usually placed them in the 7–14 girls’ size ranges, but girls who were developing breasts in fifth or sixth grade often found themselves awkwardly stuck between girls’ and women’s fashions. Girls’ dresses were too short and the wrong shape; Junior and Misses styles might fit but often looked too mature. Sears’ clothing for “junior high girls” in the 1960s and ’70s gives us a glimpse into the early stages of age compression, or “kids getting older younger” (KGOY). This concept—younger and younger children adopting styles and products initially designed for an older age group—has been controversial for years. We might think of this today as thong underwear and colored lip gloss marketed to five-year-olds, but in the late 1960s and early 1970s it was a bit subtler. The Junior section of the Sears spring 1967 catalog featured popular model Colleen Corby (born in 1947) in an outfit that in style and sizing was aimed at young women about her own age, in the high school to college age range. Modeling separates in bright, bold stripes, Corby appeared in what had already become a typical “Junior” pose: a wide stride, as if the photographer caught her mid-frug. Both the A-line skirt and sleeveless dress are about three inches above her knee, in contrast to Misses styles of that season, which just skimmed the knee. Corby’s shoulder-length hair is in a long, off-center braid when she models the pants outfit. Every detail would match well with campus styles from 1967 to 1968. In 1970 Sears introduced a young teens line called “The Lemon Frog Shop,” sizes 6J to 18J, described as for girls from eleven to fourteen years of age. Colleen Corby, by then in her early twenties, is a featured model. The Lemon Frog styles include a midriff-baring top, hip-hugger pants, and mid-thigh-length micro-miniskirts worn with knee socks. Corby and the other models have their hair in pigtails or looped braids. Whether these styles looked little-girlish or sexy depended on both the wearer and the viewer. Even more problematic is the reality that from this point on, clothing for preteen girls could be both little-girlish and sexy.

“Natural beauty” was not achieved easily, even for women in their late teens and early twenties. Stiff, pointed bras and constricting girdles were out, but a smooth line under clothes was even more desirable when the clothes were made of slinky knit fabrics. Not everyone wanted to go braless—or could. Enter pantyhose, bodysuits, and soft-cup bras. Rudi Gernreich’s soft, unstructured “no-bra bra” was specifically intended for women who wanted to “fake the braless look.”13 Young girls in minidresses replaced both girdles and regular hose with pantyhose, including patterned styles that drew attention to the expanse of leg.

Slacks were revealing in new ways, especially if they were fashionably tight. Vogue’s fashion adviser noted the need for a panty girdle, or even pantyhose with a panty girdle over them, for “smooth thigh transition.” To be a woman, especially to be a lady, was to be restrained. Not just restrained physically by foundation garments and shoes but also restrained socially, economically, and culturally. However, although discarding girdles and bras gave women physical comfort, in some ways it gave them less freedom. After all, now the control was exerted through exercise and dieting.

One way to interpret this trend toward greater body consciousness is that it helped create a culture that redefined “fat,” by changing how clothes fit, and also marginalized fat women by rendering much fashionable clothing unwearable. But a closer look at the choices available also reveal how some trends could be used to dramatic effect by fat women, following the example of singer Cass Elliot of the Mamas and the Papas, a woman who, although she loved fashion, didn’t match designers’ vision of the new body yet managed to negotiate an image that was right on trend—and fabulous.

The Mamas and the Papas’ first big hit, “California Dreamin’,” was released in December 1965 and dominated the charts for the first three months of 1966. They represented not just a new sound, folk rock, but also a new look for groups. Instead of carefully coordinated costumes, they each wore what they liked. The look of the group seemed to symbolize a new, free way of living, each person absolutely idiosyncratic. From the beginning the star of the group was Cass Elliot, who was big in every way—big personality, big voice, and a big body. At just over five feet tall, the former Ellen Cohen from Baltimore was reported to weigh more than 200 pounds.

People who wrote about her found it impossible to ignore her size, which they mentioned directly, or metaphorically, as when Newsweek described her as “that volcano of sound.” As Time’s reviewer pointed out, former model Michelle Phillips’s willowy frame was a dramatic contrast to “Big Bertha” Cass. Of course no one ever gave the weight of the two “Papas.”

Stories of her life reveal a woman who especially loved glamorous, feminine styles. In high school Cass refused to dress according to the rules and was well known for her eccentric dress: Bermuda shorts paired with high heels and white gloves. A pre–Mamas and Papas boyfriend recalls that she always dressed impeccably and in a very feminine style, favoring big hats, pretty scarves, and flouncy dresses. When “Mama” Michelle Phillips opened the door to her New York flat and first laid eyes on Cass Elliot, she was also just starting to feel the effects of her very first hit of LSD. Seeing Cass in a pink angora sweater, great big false eyelashes, and hair in a bouncy flip, Phillips recalled, “I remember thinking, ‘This is quite a drug.’”14

Despite her public self-confidence, Cass was privately uncomfortable with her weight, which varied from 180 (after a particularly intense bout of dieting and diet pills) to more than 300 pounds over the course of her career. Still, she dressed herself enthusiastically and found plenty of styles she adored in the flowing lines and visual effusion of the mod and hippie eras. Relying on personal dressmakers, she created a blend of current styles—miniskirts, caftans, custom-made boots—and old Hollywood sparkle and glamour. She and Michelle had many of their stage looks created at the same Hollywood boutique, Profile du Monde, which specialized in made-to-order clothing from sari silks.15 In her solo career as well, Cass embraced Hollywood glamour. The performances began with Cass, in a beaded gown, being lifted onto the stage by an elevator. According to reviewers of her final appearances, in 1974 in London, she looked “glittering, stunning and magnificent,” “like a pink sunrise.”16

If she had lived, she would have joined the pantheon of super-size, glamorous female singers: Kate Smith, Aretha Franklin, and others. But instead she died at thirty-two, first attributed to choking on a ham sandwich, but then discovered to have been a heart attack, which the headline writers swiftly translated into “obesity.” But in her heyday with the Mamas and Papas, she received the lion’s share of the fan mail and was often surrounded after their concerts by young girls asking for her advice. In an era where “do your own thing” was a mantra for the young, Cass Elliott’s personal style showed that it could mean for the “rest of us” above a size six. Like her contemporary Barbra Streisand, she was not conventionally pretty. But as Esquire noted in 1969, “What Streisand did for Jewish girls in Brooklyn, Cass Elliot was doing for fat girls everywhere. The diet food people must have hated her the way nose surgeons are said to hate Streisand. While the Mamas and Papas were defining a lifestyle for their fans to emulate, Cass was redefining the concept of beauty among the young.”17

Cass Elliot epitomized the female archetype of “earth mother,” a label often applied to her (“Cass looked like the mother of all mankind,” “Earth Mother in a muumuu”18) that combines size and procreative power. Her solo debut album, “Don’t Call Me Mama Anymore,” was an attempt to shed both the “Mama Cass” moniker and the maternal image, but she was fighting an uphill battle when it came to the fashion industry. There is a long-standing relationship between weight and “motherliness” in women’s clothing; plus-size powerhouse Lane Bryant began with maternity clothes before expanding into “mature styles,” which also happened to run larger than the Misses range. Determined not to be left out of the Youthquake, Lane Bryant put on a fashion show in 1968 featuring above-the-knee skirts for “stout women.” The New York Times described the models as “fuller,” “chubby,” and “plump” but also as “motherly” and “grandmotherly.”19 A young, full-figured woman, frustrated by the matronly looks in the ready-to-wear marketplace, could look to celebrities like Mama Cass Elliot for inspiration.

Jeans were a childhood favorite. For many American kids, blue jeans were the play clothes of choice. Perfect for backyard games of cowboys and Indians, jeans were also often soft from years of wear if you were fortunate enough to have older siblings who broke them in. Sears catalogs throughout the 1950s and early 1960s displayed classic denim jeans in children’s sizes 2 to 6 or 7 without gender distinction. Baby boomers may have dressed like little ladies and gentlemen at school and on Sundays, but our freest times were in jeans.

Jeans were sexy. No sooner had we outgrown backyard games than we discovered the allure of jeans on young bodies. James Dean and Marlon Brando. Girls in jeans, looking tomboyishly cute. You bought them to just fit, shrank them to fit closer, and then let them adjust themselves to your body over months or years of wear. The marriage of jeans and rock music sealed the deal. Grown-ups hated them both, which made it even better. Jeans were a blank, neutral canvas. If the ad men had their gray flannel suits and ladies had their little black dresses, we kids had our jeans. New, dark indigo jeans were practically formal and could be paired with a sport coat, leotard top, or dashiki. Once they softened up and started to rip, they could be held together with patches, appliqué, or embroidery, or lead new lives as shorts, skirts, or even shoulder bags.

At first everyone was wearing basic dungarees, and that meant women were usually wearing men’s jeans. But that was soon to change. The first Gap store, selling just Levi’s jeans and records, opened in 1969 in San Francisco. The key to the store’s success, besides a savvy exploitation of the generation gap (thus the name) was that they carried every size that Levi’s made, guaranteeing a perfect fit for men and women. One of the biggest brands of the 1970s, the Ditto brand of jeans was created when owner Richard Jaffe realized that young women were buying young men’s jeans because they liked the fit and construction. So he created a line of jeans that were tagged with both men’s and women’s sizes. Then Ditto produced men’s pants (in construction) made for women to wear (curvy, with booty-emphasizing seams). By 1974 women and girls were buying 98 percent of Ditto’s production. The company’s ads were usually a close-up of a woman’s rear end with a man’s hand on or near it, emphasizing the cut of the jeans and the way it curved around the woman’s butt. In less than a decade, jeans had gone from masculine, to neutral, to gendered and sexy, which is pretty much the story of unisex fashion for women in a nutshell.

How was unisex fashion connected to the various strands of femininity, feminism, and sexual liberation that wove through women’s lives in the late 1960s and early 1970s? It is tempting to say that it was figment of high fashion designers’ imaginations, but designers do not work in a vacuum. They respond to what is happening around them, in the arts, in the street, in diners, and in four-star restaurants. What was in the air was change, with no clear future direction. Women, particularly white, middle-class women, had been moving toward greater equality and self-determination since the turn of the century. The seductive detour through the suburbs had been satisfying for some, but Betty Friedan had correctly detected growing dissatisfaction with its limits. Astute marketers sensed that some women were looking for new sources of self-actualization and fulfillment. Of course this disillusionment with the postwar American Dream did not extend to those who hadn’t yet achieved it, so the old messages needed to be revised, not totally discarded. America’s fascination with sex was pushing the boundaries in film and literature, and between Cosmopolitan and the Pill, the sexual double standard was being challenged. For women in particular the sexual revolution centered on the decline of premarital chastity and with it the delusion of “technical virginity,” which defined everything short of actual intercourse as “not sex.” The birth control pill made “free love” possible, the new music made it attractive, and the fashions made it visible.

The postwar babies were approaching prime fashion consumer age, creating opportunity and confusion for manufacturers and retailers. Both the sexual revolution and second-wave feminism were generationally based; the children were renouncing the world of their parents. In a market where half of the population was under the age of twenty-five, the sanest course seemed to follow the young. But that assumed they knew where they wanted to go.

The most futuristic versions of unisex demonstrate the limits of unisex dressing for women—for example, the costume designs for Star Trek (1966–1969), 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), and Space: 1999 (1975–1977). The body-hugging clothing assumed to await us in the future revealed the figure, making the wearer’s sex obvious. Women still wore body-shaping underwear, makeup, and jewelry; men did not (except for male aliens, apparently). Futuristic unisex was more practical, perhaps, but made physical differences even more apparent.

What about the other styles was considered unisex? Menswear influences, or downright appropriation of masculine signifiers such as neckties, had been a feature of women’s fashions for centuries. Although these trends multiplied during the late 1960s and 1970s, the final effect was not that women’s clothing became more masculine, it was that most of the elements they borrowed became either feminized (like jeans did) or were no longer considered masculine.

What the gender trends in women’s clothing reveal is the opening of a conversation about femininity—its definition, its desirability, its naturalness, and its expression—amid an even more serious discussion of women’s place in society. The profusion of options and rejection of old rules of propriety meant that women had more freedom to choose among an even greater abundance of options. About twenty years ago one of my doctoral students, a young woman from Korea, embarked on an independent study of American fashions of the 1970s. Having been a teenager in another country at the time, she had no memory of the period and relied entirely on Vogue magazine for her paper. While she did an excellent job of primary research, I realized that I had worn hardly any of the trends she identified. Consulting my personal photo albums, I realized why: I had made just about everything I wore, except jeans and T-shirts. Not only were my clothes home-sewn, but the patterns I used were also heavily modified, as I took the “do your own thing” dictum to heart. My fashion bible was not Vogue or Mademoiselle, but Cheap Chic.20 This 1975 guide to alternative fashion by Caterine Milinaire and Carol Troy was the Our Bodies, Our Selves of fashion for many women, offering inexpensive ideas for creating an individual style. In the 1970s my mother would ask me what the right hemline was “this year,” and there wasn’t one: it depended. Everything depended—on the weather, the occasion, and one’s mood.

The New York Times noticed this proliferation of choice in 1968, reporting so many different trends that the only common theme they could find was escapism. Some women’s clothing was dressy, glamorous, and exotic, but casual looks were invading places and occasions where they once had been prohibited. Hems ranged from micro-mini (a few inches below the crotch) to floor-sweeping “granny” length. The economy was booming, and consumers were buying—everything, it seemed. The new eclecticism was even showing up in rock ’n’ roll bands. The Beatles had abandoned their look-alike mod suits for an idiosyncratic mix of vintage, uniform, and Eastern styles. This stylish abundance—and confusion—lasted through the late 1970s. The August 1973 issue of Mademoiselle shows young women from various colleges wearing everything from houndstooth check pants, to jeans, to above-the-knee skirts, to maxi-skirts, to midi-length skirts.

This suggests a temporary shift away from something I call “personality dressing,” referring to the common women’s magazine trope that asks, “What kind of woman are you?” and then offers style and grooming advice based on the responses. For example, in 1965 Seventeen featured “Personality Types and the Clothes That Go with Them,” using the categories “dainty vs. sturdy,” “dramatic vs. demure,” and “dignified vs. vivacious” for three pairs of outfits.21 A fragrance ad from the same year offers just three choices: “romantic,” “modern,” and “feminine.”22 Clara Pierre, noticing the same trend, used the term “event dressing” for the new, more situational rules, but I think the term “moment dressing” is more descriptive.23 Which outfit came out of the closet depended not only on the occasion but also on the woman’s mood at the moment. Moment dressing was a sign that the essentialist view that women came in a few, easily categorized varieties was passé, at least for a while. Like the W-O-M-A-N in the Enjoli perfume commercial who could “bring home the bacon, cook it up in a pan, and never let you forget you’re a man,” the woman of the 1970s could do anything, or at least dress for anything.

All fashions end; that’s why they are called “fashions,” not paradigm shifts. It was inevitable that trends so generationally driven would change as the leading edge of the baby boom reached their late twenties and thirties. Careers replaced summer jobs, and suburban houses replaced dorm rooms. The economy tightened, and there was less money to spend on whimsical clothing, bringing classics back to center stage.

Although women had made significant gains in civil rights—equal opportunity in employment, Title IX opening up school athletics, the ability to establish credit and financial autonomy—second-wave feminists still felt they had unfinished business, but there were signs of public fatigue and, more seriously, backlash. In the nine years between the publication of The Feminine Mystique and the passing of the Equal Rights Amendment, while some women were raising their consciousness and reading Ms., significant countermovements had also gained strength. Blue-collar women, lesbians, and women of color were excluded by the feminist leadership’s emphasis on finding a place for women within the existing societal structure. These fissures within the women’s movement existed early on, at the ironically named Congress to Unite Women in 1969 and 1970. Appearances had something to do with it, just as they had during the first women’s movement in the nineteenth century. Amelia Bloomer, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and others had abandoned dress reform and the revolutionary outfits associated with it in the 1850s, because they were convinced the clothing was distracting from the “real issues” of women’s rights. Betty Friedan and others in the National Organization for Women leadership were afraid that activist lesbians, especially the more visible, “mannish-looking” ones, would attract too much hostility and negative press, thus hindering the movement.

Stereotypes are stubborn things. Just as the suffragists had been lampooned as pants-wearing Amazons for decades after the Bloomer costume disappeared, the popular image of the bra-burning, man-hating, hairy-legged feminist became lodged in the popular consciousness. Never mind that the bras in question (outside the Miss America pageant in 1968) were tossed in a trash can (along with mops and fake eyelashes), not burned. The July 1973 issue of Esquire, proclaiming on the cover “This Issue Is about Women,” is a snapshot of the male response to feminism. While including young journalist Sara Davidson’s straightforward history of the modern women’s movement and a thoughtful set of interviews with men who were sympathetic to the cause, the issue also included such choice pieces as a chart of the women’s liberation leadership titled “Women Who Are Cute When They Are Mad” and a satirical piece asking “What If . . . Gloria Steinem Were Miss America?”24 The answers:

People would say she won because she dated Bert Parks.

She would not have won Miss Congeniality.

Her talent would be a modern dance interpretation of the Bell Jar.

She would accept a $5000 wardrobe consisting of three dozen turtlenecks, a gross of T-shirts and 250 pairs of jeans.

She would wear purple aviator contact lenses.

She would still be a royal pain in the ass.25

Not all women were enthusiastic feminists, either. Some were devotees of Helen Andelin’s vision of power femininity, a movement that gained a political face with the emergence of the new conservative leader Phyllis Schlafly. Schlafly organized a STOP ERA movement that was instrumental in blocking or rescinding ratification of the amendment before the deadline in 1982. (STOP stood for Stop Taking Our Privileges, a reference to Schlafly’s contention that the ERA would end women’s protected status and result in women being drafted and everyone being forced to use unisex bathrooms.) Probably one of the most articulate expressions of intellectual opposition to women’s liberation was George Gilder’s Sexual Suicide (1973). Like many other critics, he argued that the prevailing culture exalted women and gave them a privileged place in society. But he also noted one of the basic problems with the liberation movement—and perhaps the social reform effort. He responds to a question posed by Nora Ephron in an article for Esquire: “What will happen to sex after liberation? Frankly, I don’t know. It’s a great mystery to all of us.” “Ms. Ephron is honest and right. The liberationists have no idea where their program would take us. The movement is counseling us to walk off a cliff, in the evident wish that our society can be kept afloat on feminist hot air.”26

Women’s fashions begin to reflect these changes in the early seventies as dresses made a comeback. When twenty-two-year-old Diane Von Furstenberg arrived in the United States in 1968, she found a chaotic, disappointing mix of “hippie clothes, designer clothes and drip-dry polyester.”27 There was nothing, she believed, for young mothers or working women, and she felt there was an untapped market for “simple sexy little dresses” that were comfortable, easy to care for, and figure-flattering. The result was her iconic knitted jersey wrap dress, which she modeled herself in a full-page ad in Women’s Wear Daily. The unstructured dress, with its modest length and sexy slit skirt and V-neck, was a gigantic success and was seen everywhere, whether in the original version or any of the many knock-offs, and is credited with wooing women away from pantsuits.

Influential as the wrap dress was, it was also well timed, not just great design. Women’s fashions were acquiring a vintage sensuality, propelled by nostalgia for the 1930s in popular culture and design. One barometer of this trend is Frederick’s of Hollywood, known in the 1960s mainly as a mail-order purveyor of hard-to-find lingerie items. Frederick’s claimed to have invented the push-up bra and offered not only a sexier selection of bras than Sears or Montgomery Ward, but also pasties, crotchless panties, padded girdles, and, in the late 1960s, sex toys and how-to manuals. The firm went public in 1972 and opened 150 stores in the next eight years, becoming a fixture in suburban malls. Competition was not long in coming; in 1976 Bloomingdale’s department store hired French photographer Guy Bourdin to create “Sighs and Whispers,” a lingerie catalog that created such a sensation that original copies sell today for hundreds of dollars. Women in skimpy, even scandalous undies populate the dramatically lit tableaux. They are not just lounging passively, but jumping and dancing. They even “flash” the reader, revealing see-through bras under filmy negligees. In 1977 Victoria’s Secret upped the ante with more sophisticated unmentionables, reminiscent of pre–sexual revolution boudoirs, but with a postrevolutionary frankness.

The final element in the shift in women’s fashion was the publication of Dress for Success for Women (1977),28 John T. Molloy’s sequel to his 1975 best-selling book for men.29 In his introduction he described the biggest problem facing women in the professional workplace: the lack of appropriate office styles for women with aspirations beyond the secretarial pool. The available choices were usually too casual and either too mannish or too sexy. Like the original men’s version of Dress for Success, Molloy’s advice was based on his own extensive research, most of it for businesses that hired him to provide guidance to their own employees. Since I’ve already admitted that I did not read any of the three most influential books for women published in the early 1960s, I’ll confess that for my research for this book I used my original paperback copy of Dress for Success for Women, purchased in 1978 when I was in graduate school. By the next year, every female grad student in my department owned a “success suit” as described by Molloy in the chapter by the same name: a blazer-style jacket and a skirt hemmed just below the knee, worn with low-heeled, plain pumps. My suit was deep maroon wool, one of his “approved” colors. Mass merchandisers lagged a bit in adopting the style; Sears and Montgomery Ward showed their first Molloy-style outfits in fall 1979. But they usually offered separate pieces, not suits, and always included matching trousers, an option Molloy did not endorse. “The pantsuit is a failure outfit,” he warned, except in female-dominated workplaces.30

By the late 1970s skirts and dresses were back for work and formal occasions, pants were uncontroversial (but had been feminized with colors and trims), and lingerie sales were up. But were these steps backward or forward? If you believed that dresses and sexy underwear were the tools of patriarchy, you saw retreat in these events. If you believed that clothing, including power suits worn with a lace-trimmed slip, was your ticket to the executive suite, you saw progress. If you believed that gender differences were a moral imperative, you would be very pleased that women were “dressing like women again.” The one permanent change was that the monolithic image of women had been shattered, or at least had a few cracks in it.

Fashion historian James Laver, observing the clothing of Great Britain in the early 1960s, mused, “When a woman becomes emancipated, you would think she would go in for an orgy of femininity. Instead she flattens her figure and cuts off her hair. She did it after World War I and again after World War II.”31 He found this behavior contradictory, but I don’t believe it is. Women’s rights movements have been, at least in part, a rebellion against the cultural construction of femininity, what Betty Friedan called “the feminine mystique,” probably because these supposedly innate characteristics of women—kindness, emotionality—have too often been used to define our place and then confine us within it. Trying to break away from that confinement means engaging with the cultural products that connect the female and the feminine, sex and gender. For clothing that can mean reassessing either the fashions we wear or the industry that creates and promotes them—or both.

Bras and beauty products were thrown in the trash at the 1968 Miss America pageant as a protest against the artificial construction of femininity, yet both lingerie and cosmetics are bigger business today than they were forty years ago. Cosmetic surgery, just in its infancy in the 1960s, has grown as the baby boomers have aged. Was fashion a form of oppression created and perpetuated by patriarchy or a pastime enjoyed by many women as a means of self-actualization? There have always been many views on fashion among feminist activists and thinkers. There is no single feminist perspective on fashion; there is a multitude. One of the oldest conflicts within the feminist movement has been the one between people who wanted to eschew fashionable clothing and those who believed it was an important form of personal expression.

How deep were the changes in women’s dress from this era, and how many of those changes persist today? Attempts to develop unisex clothing in the 1970s had about as much success as the Bloomer costume did in the 1850s. Doors were opened and new choices appeared, but it is difficult to argue that the cultural construction of femininity in 1980 was radically different from what it had been in 1960. Even though women had adopted pants, most preferred to wear trousers that fit their curves and were worn with blouses and sweaters that were designed for women, not men. Two changes appear to have been permanent: greater sexualization of clothing and the demise of many of the old rules of etiquette that had governed dress. These two trends were not unrelated. “Sexy” clothing had long been permitted or denied according to age, marital status, profession, and occasion as one element in a complex set of rules within broader gender codes. What was worn in the bedroom, ballroom, or bawdy house varied according to subtle standards learned through popular media. In 1963, movie streetwalkers such as those in Irma la Douce, were immediately recognizable because they wore exaggerated makeup in the daytime, boots when it wasn’t raining, and very short skirts. Ladies wore white gloves and hats and donned pants for only the most casual activities. By the late 1970s women had abandoned white gloves and hats and wore pants everywhere. Sandals, once considered strictly beachwear, appeared in offices across the country. Some of these rules had separated casual from formal, public from private, and girl from woman. They also helped to communicate one’s availability for flirtation or more. Without the rules were all females sexy? Did that become part of the basic job description for all girls and women? That may be one unintended legacy of the sexual revolution.