Nature and/or Nurture? |

4 |

Where do masculinity and femininity come from? After all, it is fairly obvious that newborn humans have neither set of qualities. Yet by the time they are two or three years old children not only know the rules, but they also have become its primary enforcers, as any observer of a preschool playgroup can confirm. With the women’s movement challenging traditional female roles and popular culture offering a range of new expressions of modern masculinity and femininity, it seems inevitable that children would get swept up in the excitement and confusion. If nothing else, the link between adult and children’s clothing would mean that kids and grownups would wear similar styles. This clearly happened during the 1960s and ’70s, but there was something else at work too. Emerging scientific evidence pointed to gender roles being learned and malleable in the very young. This affected children regardless of where their parents stood on women’s rights or sexual morality. Given the drive to transform women’s roles and promote gender equality, it’s likely that if you were born between the late 1960s and the early 1980s, you experienced non-gendered child raising to some extent. If you didn’t wear your sibling’s hand-me-down Garanimals outfits, the kindergarten teacher might be reading William’s Doll to you at story time. Or you might be singing along to your Free to Be . . . You and Me record on your Fisher-Price record player, after watching Sesame Street, which featured Susan Robinson as a working woman who liked to fix cars in her spare time.1

Looking at children’s fashions we can see just how complicated the ideas and arguments were during this period. There were so many different popular beliefs about sex, gender, and sexuality, mixed with parental ambivalence, disagreement, and anxiety about the right way to raise children. In this chapter I describe changes in children’s clothing styles and place them in the context of the competing scientific explanations of gender and sexuality. I also address how well those were understood and accepted by the general public. As children of the unisex era grew up, their reaction to ungendered clothing became apparent in the ways they dressed their own children. Not that we are that much closer forty years later to knowing where gender comes from. We’re still arguing over gender, gender roles, sexuality, and sexual orientation. Whether the hot topic is marriage equality, the Lilly Ledbetter Act, or gender-variant children, beliefs about nature and nurture in determining our personal characteristics are fundamental to the arguments. Some of those beliefs are based on religion, others on science, but many of them are likely echoes of forgotten lessons learned in early childhood.

A note about the messiness of studying the history of childhood is in order. While studying gender expression in adult fashions can be complicated, the task is even more daunting when we turn to children’s clothing. Babies don’t pick their own clothing, which reflects adult tastes and preferences. After all, how many week-old Yankees fans are there, really? It’s not surprising, then, that of the 762 individual specialists listed in the Costume Society of America directory, only 19 report expertise in children’s clothing. In American consumer culture, children begin to have some say in what they wear when they are toddlers, between the ages of one and three years. Sociologist Daniel T. Cook has argued convincingly that American preschoolers have been consumers-in-training since the dawn of the twentieth century, which means that several generations of us have grown up to accept the spectacle of an adult arguing with a three-year-old over the relative merits of a tutu or a sundress for a trip to the mall.2 Our great-great-grandmothers would have brooked no such behavior: children wore what Momma bought or made, period. In short, beyond infancy it is hard to know the extent to which the wearers or their parents are driving trends in juvenile clothing. Children’s voices are missing from the popular history of the 1960s, and although it is possible to interview grownups about their childhood memories, the problem is that adults’ memories tend to be selective and influenced by later experience, hindsight, and nostalgia.

The most abundant source of information about children’s fashion is mail order catalogs from various time periods. Until the mid-1980s the retail giants in children’s wear were Sears, Roebuck and Company, Montgomery Ward, and J. C. Penney, who together accounted for a quarter of the infant and toddler market.3 The structure of the children’s clothing market beyond these big three department stores was similarly limited. Unlike women’s apparel, with its many designers, manufacturers, and retail outlets in all sizes, a significant proportion of children’s clothing was produced by a handful of companies. A few large manufacturers such as Baby Togs, Carters, and Health-Tex dominated the market, reaching consumers through local department stores or national chains. Pattern companies like Butterick and McCall’s were still important players as well, at a time when most women learned the rudiments of sewing in school. Home sewing enabled women to modify current fashions to their own tastes and abilities, giving them more choice than is available today. When I examined the trends in infants’ and children’s clothing for this period, I drew mainly on the plentiful images available in catalogs and pattern books, along with the observations of industry reporters such as Earnshaw’s. If your childhood was middle-class and mainstream, much of this will ring true.

Children’s clothing choices are not simply a matter of taste—a favorite color or cartoon character, a dislike for scratchy fabrics—they are also a way that children try on, rehearse, and express their burgeoning identities. Even two-year-olds have a rudimentary understanding of the prevailing gender rules. In fact it is striking to consider how complicated the “rules” are—far beyond pink for girls, blue for boys—and what an accomplishment it is that young humans master them over the course of early childhood.

In Pink and Blue: Telling the Boys from the Girls, I offer a more detailed description of these complex rules and how they have evolved since the late 1800s, which I will summarize here.4 The main point is that not only have the rules for boys and girls changed, but so has the definition of “neutral” clothing. Our traditional conception of gender may be a simple either/or binary, but the actual costumes and props with which we enact those roles are not. In addition to gendered clothing—designed according to shifting standards—there have always been other options, be they called “neutral,” “unisex,” or just “children’s.”

Before the twentieth century all babies wore long white dresses; slightly older boys and girls wore dresses and skirted outfits that were shorter and more colorful than baby dresses. Neither style indicated the child’s sex, because that would have been considered horribly inappropriate. Pants were considered so quintessentially manly that women and girls could not even wear underdrawers until the middle of the nineteenth century. The timing of a child’s graduation from baby to boy was a matter of taste and parental perception; the growth spurt that transformed the chubby toddler into a taller, leaner child was one sign that his masculine nature was about to manifest itself. Other parents might select their son’s first pants in time for his first day at school, or they might watch for signs of “manly” behavior before putting his dresses away. Parents in the 1880s did not believe that boys needed masculinity lessons any more than they needed instruction in crawling, walking, or talking. The advice was just the opposite: pushing a baby into boyhood too early was dangerous, because he might become sexually precocious.

Freudian psychology and social Darwinism replaced this long-held view that identity was innate (or “nature”), with the opinion that while sex may be innate, sexuality was learned—nature strongly influenced by nurture. They also mingled what we today would call gender—masculinity and femininity—with aspects of sexual orientation. As sexuality historian Hanne Blank points out, this particular “nature plus nurture” hypothesis has turned out to be an imperfect explanation, and the scientific evidence once used to support it has been largely discredited.5 There is, however, a stubborn cultural insistence on reducing complexity to binary choices (nature or nurture, male or female, masculine or feminine), which encourages even more stereotyped thinking. All men are not aggressive, all women are not passive; most gay men are not effeminate, and vice versa. Within the categories we have constructed there is huge variety, which binary, stereotyped thinking ignores.

One telling indication that these notions of gender had a cultural bias is the inconsistency with which gender-variant boys and girls have been treated. Science alone could not explain why “tomboyism” was an acceptable and even desirable stage in girls, but “sissyish” boys needed stern correction and psychological treatment. The homophobic subtext of the works of G. Stanley Hall and other child psychologists clearly indicates that unmasculine behavior in little boys was perceived as pathological while similar, unfeminine behavior in girls was “normal.”

Once nurture had been introduced as a factor in sexual development, the bulk of twentieth-century studies of gender development were devoted to trying to figure out how nature and nurture interacted and which was more powerful. In the meantime, parenting advice was constantly changing, as any woman can verify who lived near her own mom or mother-in-law when her children were small. Each generation had its own experts who published books and articles denouncing their predecessors as old-fashioned and unscientific and dictating new approaches to infant and child care. Attitudes about gender and sexuality were part of this turmoil. In the first half of the twentieth century, many people apparently held a composite belief that gendered behaviors were present in an immature form at birth and developed as the child grew but that sharp gender distinctions could wait. In their view baby boys were male but not masculine, although they contained the germ of masculine behavior. Babyishness would become boyishness as the child matured, inevitably ending in manliness. Male babies and small boys, not being physically mature enough to dress like men, wore clothes that were appropriate to their tender years and subordinate status. In those days decorative touches such as smocking and embroidery were as acceptable on a baby boy as they were on a girl. A male toddler’s long curls were charming and baby-like. To the extent that little boys’ clothing was distinguished from that of girls, it was along much subtler lines than that of older children and adults. Babies—even male babies—were fragile, vulnerable, and soft; strongly masculine clothing was just not suitable. The widespread use of pastel colors for infant furnishings reflects this view, as does the incorporation of details like rounded collars and puffed sleeves.

The ungendered children’s clothing of the nineteenth century was gradually discarded in favor of a complicated and regionally variable pattern of boy-girl symbolism. The iconic use of pink and blue, for example, spread unevenly throughout the United States between 1900 and the 1940s. As late as the end of the 1930s pink was a perfectly acceptable choice for baby boys in some parts of the South. Pastel pink and blue used together continued to be a traditional combination for baby gifts and birth announcements through the 1960s. Dresses for boys, on the other hand, went out of fashion fairly quickly. For toddler boys they were rare after 1920, although the use of white baby dresses for newborns continued into the 1930s and ’40s. By 1960 boys never wore dresses outside of a christening ceremony, and even under those circumstances suits with trousers or short pants often replaced dresses. On the other hand, overalls, pants, and shorts for girls became so commonplace that by the 1950s knit shirts and jeans were as neutral for American children as white baby dresses had been for their grandparents.

For the children of the 1950s and early 1960s who have no historical memory, the gender rules for clothing of that time were “traditional.” From their parents’ point of view, the more gendered styles for babies and toddlers were an innovation, as were the more masculine styles for little boys, complete with neckties and long trousers. For parents who preferred them there were still plenty of neutral choices for babies and toddlers. Compared to the styles available in our own recent times, there was actually considerably more leeway available in the ’50s and ’60s. Pink and blue had become nearly universal symbols of femininity and masculinity but lacked the moral imperative of modern “pinkification.” Like wearing green on St. Patrick’s Day, dressing baby girls in pink and boys in blue was a lighthearted custom, not a requirement. Other pastels—yellow, green, and lavender—were convenient and popular choices for baby shower gifts and for thrifty parents planning a large family and lots of hand-me-down clothing (or people who simply thought their baby looked best in those colors). Baby boys’ fashion had not yet acquired the “just like daddy” style and still might incorporate decorative elements that in another generation would be considered feminine. The spring 1962 Sears catalog offered embroidered, sleeveless “diaper shirts” in packages of three—all white or one each of pink, blue, and yellow—and dressy outfits for infant boys that were babyish, not at all manly (unless you count the tiny pocket and the mock fly stitching on the front of the underpants). Some girls’ clothing was sufficiently feminine that no boy could wear it, but boys’ styles tended to be so plain that they could be appropriate for girls as well.

Toddler clothing for dressy occasions was sharply gendered; party and holiday fashions featured pastel-colored Eton suits with short pants and bow ties for boys and frilly dresses worn over poufy underskirts for girls. But play clothes usually consisted of overalls and polo shirts for both boys and girls, with a few feminine styles included as “fashion items.” The lowest-price items, often sold in packs of two or three, were nearly always neutral styles, and the more gendered items were likely to be the most expensive. This reveals an important element of gendered clothing for children at a time when clothing was still relatively costly: neutral clothing was more economical in the short run (when first purchased) as well as in the long run (as hand-me-downs). But cost was not the only consideration. Had parents in the early 1960s believed as strongly in gendered clothing as did parents in the early 2000s, there would have been fewer neutral choices back then.

School-age boys and girls had a range of styles and colors to choose from within acceptable bounds of masculinity and femininity, but those limits still allowed for a range of expression, at least for girls. A sewing book in 1954 suggested a wardrobe of six to eight school dresses, two party or Sunday dresses, and just two pairs of “sturdy slax” [sic] for play.6 School dresses came in a variety of styles and colors to suit every taste from tailored to frilly. In every classroom girls’ gender expression ranged from tomboys in skirts and sweaters to “girly-girls” in ruffles and bows who had their hair set in pin curls every night, not just on Saturday. Boys’ fashions, once they were no longer in the toddler size range, tracked fairly closely to adult men’s clothing, with whatever expansions or contractions of cut and color they experienced.

Throughout the period, acceptable gender expression depended not only on the wearer but also on the context, especially the setting and the activity. Neutral clothing existed long before the term “unisex” appeared, particularly for younger children and for active play clothes for all ages. Pants, shorts, and overalls were widely available in infant and toddler sizes and for the most part were ungendered long before the unisex trend began. In fact, because the younger they are, the more ambiguous their appearance, babies and toddlers modeling play clothes in Sears catalogs of the 1950s and early ’60s were more “unisex” than adults could ever hope to be. The older the child, the fewer androgynous casual styles were available. Pants and shorts for girls sizes 7–14 featured more feminine details than those for younger girls: floral prints, decorative flourishes, and side or back closures. Only classic, Western-style jeans were neutral (right down to the fly front for both girls and boys), although “girls’ jeans” with side zippers were also available. Expensive, seldom-worn children’s items such as coats and snowsuits were made hand-me-down friendly by avoiding feminine or masculine details, but the lowest-cost items were also likely to be neutral. Dressy clothes were not only more gendered for all ages but also more likely to mimic adult fashions. The girls modeling the trendiest clothes also posed like grown women, underscoring the connection between those styles and the adult fashions on which they were based. Throughout the 1950s and ’60s, “dressy” clothing literally meant dresses for girls from infancy to adulthood. Party and holiday clothing was the most elaborate and also the most feminine and masculine. Between play clothes and dressy fashions lay school clothes, which meant dresses and skirts for girls, although they were offered in a range of styles from plain to fancy.

Styles for schoolgirls, Montgomery Ward catalog, Fall/Winter 1961.

Children’s jeans, Montgomery Ward catalog, Spring/Summer 1960.

Gender patterns in children’s clothing shifted between 1962 and 1979 in ways that parallel the changes in adult clothing. For most of the 1960s the postwar rules prevailed: younger children had more neutral options than school-age boys and girls. The dressier the occasion, the more gendered the clothing. The clothing for active play was decidedly “masculine” and located in the boys’ section of the catalog. A page from the fall-winter 1964 Sears catalog is typical. A boy and a girl are shown in jeans and striped T-shirts; no “boy” or “girl” versions are offered either in sizing or in style.

Like Victorian fashions, mid-century styles continued to mark age distinctions from infancy to adulthood, though with fewer rigid rules. No longer restricted to short trousers, toddler boys now enjoyed a greater range of colors and patterns than older boys and men. Younger girls’ fashions were shorter and more whimsically decorated than those for older girls and women. Party and holiday fashions for little girls featured frilly dresses worn over poufy underskirts, not child versions of women’s trends. Misses styles could be more revealing and more sophisticated than the Junior fashions designed for high school and college-age consumers. Different flavors of femininity were available depending on age and dating or marital status. Little girl femininity was dainty, pastel, and whimsical. Bigger girl femininity was ladylike and paid attention to current trends and to becomingness (colors that flattered the girl’s complexion, for example). Teenage clothing was trendier and figure-flattering, but not revealing. “Sexy” was for adult women.

Children’s play clothes, Montgomery Ward catalog, Fall/Winter 1960.

McCall’s unisex vest pattern, 1980. McCall’s M7269.

Image courtesy of the McCall Pattern Company, 2014.

The innovative styles popular with adults in the late 1960s were available for children, including pantsuits for girls, collarless or Nehru jackets for boys, and turtleneck sweaters and shirts for both. Many of the options for boys and girls were truly neutral, with no strong, preexisting gender significance. Most of the neutral styles were based on adult unisex trends, including hairstyles like the Afro and novelty items such as caftans, ponchos, and belted sweater vests. Styles such as turtleneck sweaters, T-shirts, sweatshirts and sweat pants, and jeans, which had been acceptable casual wear for both boys and girls for some time, became more popular and permissible for a wider variety of occasions. Some of these represented new classics, which have continued to be available ever since the 1970s. By the late 1970s feminized versions of once masculine or neutral styles were appearing such as turtleneck shirts with puffed sleeves or denim overalls with ruffled shoulder straps. Vests survived ungendered into the 1980s.

Unisex clothing and fashion for boys meant a kind of flexibility that had not been seen in several decades: more patterns in fabric, including floral prints and bright colors generally, and more embellishment, especially embroidery. These trends echoed similar freedom in men’s clothing, described in the previous chapter. Boys’ hairstyles became longer and longer and in many cases were quite similar to girls’ hairstyles.

One interesting feature of unisex clothing for children was not only the phenomenon of designers of girls’ fashions borrowing styles from the boys’ department but also girls actually buying boys’ clothes. Sears acknowledged this practice by including size conversion charts in the boys’ pages of its catalog. Earnshaw’s reported in 1978 that as much as 25 percent of “boys’” jeans and pants was actually sold to girls. The practice also apparently reversed, though not to the same extent; one manufacturer of girls’ stretch pants and tops increased his business when he realized that mothers were buying the comfortable, easy-care garments for little boys and started including boys in his ads. To further complicate the story, the manufacturer added a “boys’” line, which girls also began to wear.7 In the same year, some feminine elements started to make a comeback. Red, yellow, or green shortall (short overall) and overall sets in the spring 1978 Sears catalog featured ruffled straps and puffed-sleeve shirts.

The unisex trend reached every member of the family beginning in 1970 when the Sears catalog that spring featured six pages of “his and hers” styles for adults (in the men’s section) and “family styles” modeled by school-age children. Toddler play clothes for boys and girls had always been grouped together, but the unisex influence was visible in fashion-forward styles mimicking adult trends: collarless jackets, longer haircuts, and bright colors for boys and pantsuits for girls. There were fewer dressy, traditional gender-specific styles for children under size 14 as casual styles dominated the scene.

“Family” fashions, in the form of coordinates for adults and children of both sexes, had been popular since the end of World War II, perhaps as a celebration of the nuclear family. These styles in early 1960s Sears catalogs reflected current trends in colorways, whether for heathered neutrals or citrusy brights, but they were limited to a page or two. For boys and men these “his and hers” styles offered a rare respite from the limited range of appropriately masculine hues. Overall one of the most striking characteristics of all clothing between 1968 and 1978 is the explosion of color and pattern that assaults the eye in every magazine and catalog. From apparel for the tiniest babies to men’s suits, each page is a kaleidoscope of stripes, plaids, and prints in brilliant colors. For the first time in generations, older boys and men were enjoying colors and expressive patterns formerly considered effeminate, juvenile, or both. Pastels for babies and toddlers were “creeping into the background,” replaced by red, white, and blue and green, orange, and yellow.8 Orange, gold, and olive green dominated kitchens and closets alike in the early seventies, and bicentennial red, white, and blue was everywhere in 1976.

Pastel pink had become a nearly universal symbols of femininity by mid-century, but dressing baby girls in pink was still optional. For most girls pink was one choice among many, and pastels in general were clearly associated with warmer weather and dressier occasions as well as gender. Spring and summer fashions featured pastels and light colors while the fall-winter catalogs were full of darker, more saturated hues. The plaid cotton school dresses familiar to so many baby boom girls were seldom light in color because they had to stand up not only to recess but to penmanship lessons with real ink as well. From season to season the colors and fabrics in the children’s sections of clothing catalogs generally followed adult trends and patterns. If burnt orange was a fashionable color, the entire family wore burnt orange.

The details of clothing trends can be overwhelming; underlying rules and patterns can be frustrating to discern amid the contract flow of colors, shapes, and patterns. They also make for boring reading. Rather than recap the trends already described in the previous chapters for women and men, most of which were transferred directly to children’s clothing with little modification, what follows is a brief summary of changes in gendered and ungendered clothing for children from birth to puberty for the years 1962 to 1979.

Two of the “bedrock” rules from the previous decades did not change: the dressier the outfit, the more gendered it was, and it was perfectly acceptable for girls to wear boyish styles for play, or even clothing from the boys department. However, some of the key existing rules disappeared, including

• age separation (babies are not toddlers are not children are not teens are not adults)

• pants for girls are for casual wear only

• neutral styles for babies may include some otherwise feminine elements (floral prints, puffed sleeves, smocking, pink and blue in combination)

A new pattern emerged during this time that not only survived the 1970s but also persists today in an even more decided form. As the age separation rule faded, the distinction between “girly” feminine and “sexy” feminine dissolved and moved lower in the age range for girls. This began with preteen or young Junior styles aimed at girls in the 10–12 age range, but by the late 1970s they were evident in the 7–14 size range as well.

One last shift that occurred during this period was the boys’ equivalent of the peacock revolution. Like teens and older men, boys enjoyed a wider spectrum of colors, patterns, and styles and wore their hair longer and longer. Like the more mature styles, this trend showed signs of disintegrating after the mid-1970s.

All of these changes together resulted in more options from which to choose. This was true for gendered clothing, which was reimagined and expanded: more pants for girls, in styles ranging from boyish to fussy, and more expressive, colorful, and even flamboyant styles for boys. But the number and proportion of styles designed for both boys and girls—the neutral or unisex styles—also increased. As a result there was more choice than had been available for children before or since. The question remained, what to choose?

Unisex clothing could be dismissed as just another trivial fashion trend, except that it coincided with heightened scientific, popular, and political attention to the differences between men and women, including the sources and consequences of those differences. Much of the excitement boiled down to a very old question: Are we products of nature or nurture? Unisex clothing posed this question not only visually, to the observer, but also in a very intimate way to the wearer. Who was right? Erasmus, when he penned vestis virum facit (often translated as “Clothes make the man”), or Shakespeare, who observed, “Clothing oft proclaims the man”? The women’s movement introduced new urgency to the question of the origins of gender roles, along with a corollary: Is it possible to explore new social roles? Almost immediately there was a conservative reaction: just because new roles were possible didn’t necessarily mean they were desirable.

For many scientists these questions were already being answered by work suggesting that nature and nurture interacted, although in unknown ways. The either/or binary choice persisted in the popular mind, however, especially when it came to children and gender. Many parents (and psychiatrists) clearly held the view that biological sex, as indicated by a baby’s genitalia, was inextricably connected to gendered behaviors. Boys were expected to be loud, tough, and active; girls were dainty, cuddly, and gentle. Children, especially boys, who did not display appropriate characteristics and interests needed correction, whether in the form of parental discipline or professional therapy.

On the other hand, feminist parents, scholars, and educators argued that traditional masculine and feminine roles were the result of social and cultural pressure, not biology. Second-wave feminists were particularly interested in challenging the sexist beliefs and structures they believed were responsible for women’s lack of power and status. Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique, in particular, was an indictment of cultural notions of femininity marketed as natural traits. In the public square this translated into protests and political activity. But for many this desire for equality resulted in a more personal, long-term goal: a new generation of men and women raised to be unrestricted by gender stereotypes. The answer, it seemed, lay not only with adults as they struggled to break out of their traditional roles, but also with children, especially the very youngest boys and girls. The solution to sexism seemed to be early intervention, in the form of “unisex child-rearing,” a movement affecting even the youngest babies. The transfer of that newly coined term from pantsuits to parenting seems to signal a shift from the “frivolous” realm of trendy young adult fashion to the serious business of cultural transformation.

By the 1970s science and popular culture converged on a paradigm shift in parenting and education. What if femininity and masculinity were almost entirely nurtured? This would place the power for shaping children’s gender and sexuality in the hands of parents and educators; medical professionals and mass media would play important supporting roles. This moment was a long time coming, beginning with the first child psychologists who had challenged the nineteenth-century view that masculinity and femininity were innate but undeveloped in babies, and that such traits naturally emerged as the child matured, without the need for coaxing or direction. G. Stanley Hall and others had argued instead that, like intelligence or musical talent, sex roles (as they were then called) were subject to good or bad influences, neglect or cultivation. Scientific evidence that masculinity and femininity were all or mostly learned behaviors would not have made the stakes any lower or the parents’ task less important. In fact, as it turned out, believing that gender roles are mostly cultural only intensified those arguments over what masculinity and femininity should be.

The work of John Money in the 1950s and ’60s not only introduced the modern concept of gender but also popularized the belief that in the process of identity formation, biological sex was subordinate to gender—that is, the cultural expressions associated with sex. At that time the leading expert in the treatment of intersex children (those born with ambiguous genitals), Money separated the acquisition of gender identity into biological and social processes. The former, he argued, began at conception and proceeded through five stages before birth. Studies in the late 1950s had established the effects of fetal hormones on brain development, a phenomenon popularly referred to as “brain sex.” At birth the external genitalia identify the baby as a boy or girl, but then gender socialization takes over and becomes the more powerful influence.9

Before the reader gets too enthusiastic about his findings, I need to point out that Money has now been so discredited that his name serves as a warning for researcher hubris. Most of his fame rested on Man and Woman, Boy and Girl, a widely used college textbook coauthored with Anke Ehrhardt.10 Besides introducing and elucidating the very useful concepts of gender identity and gender roles to a generation of college students, Money and Ehrhardt’s book is best known for the story of John/Joan, an infant boy whose circumcision went terribly awry, leaving him with an irreparably damaged penis. The solution was surgical reassignment, conducted when the child was about a year and a half old, along with follow-up therapy and hormone treatments that Money claimed produced a well-adjusted girl. The fact that “Joan” had an identical twin brother gave additional weight to Money’s claim to have successfully created female gender identity in someone born male. In addition to this famous case, Money also published widely on his “successes” with hermaphrodite (intersex) babies, who were usually transformed into girls through surgery and hormones, accompanied by behavioral therapy.

In the decades since Money’s peak influence, follow-up studies of his patients have cast a huge shadow over these claims. Not only were they often unhappy with their female bodies, but as adults his patients rejected the feminine cultural patterns foisted on them. The feminized twin on whose story Money had built this reputation eventually chose surgical reversal of the operation and wrote his own story, As Nature Made Him: The Boy Who Was Raised as a Girl. Sadly, he eventually committed suicide in 2004 at the age of thirty-nine.11 In the meantime, despite the unhappy outcome of Money’s work, surgeries on intersex infants have continued to be common practice. Overwhelmingly, these babies are still recreated as females, because male-to-female surgery is generally easier than the reverse. This represents an extreme, rare effect of Money’s work, but his work also helped propel acceptance of the belief that gender identity is socially constructed. In fact the roles of nature and nurture in human development are still controversial.

For scholars the distinction between biological sex and the expressions, behaviors, and personality characteristics associated with biological sex served a very useful purpose, seemingly isolating the sociocultural aspects of human behavior from the presumably more universal biological traits. Biological sex was a given, nearly immutable; socially constructed gender was a dependent variable, subject to not only influence by social interactions and media but also, potentially, intervention by parents, teachers, and therapists. Separating the two forces also conformed to the trend for academic specialization. Geneticists, endocrinologists, and other life scientists could focus on the physical (sex), leaving gender to the social scientists. Behavioral scientists began to scrutinize how we acquire gender in early childhood, including patterns of nurturing and education. These investigations were driven not only by scientific curiosity but also by popular demand for definitive answers. The feminist movement and the sexual revolution had opened a Pandora’s box of questions and confusion about the most basic elements of human identity.

The same year that Money and Ehrhardt published their textbook, one of the most iconic fictional works of the unisex era appeared: Lois Gould’s short story “X: A Fabulous Child’s Story,” a tale of an “Xperiment” in gender-free child raising. It was published in Ms. in 1972 and was expanded into an illustrated children’s book in 1978.12 In the story a baby, named simply X, is born to two parents who have agreed to keep its sex a secret as part of a huge, expensive scientific experiment. They are given a thick handbook to help them navigate future problems from how to play with X to dealing with boys’ and girls’ bathrooms at school.

The challenges grow larger and thornier when X enters the gendered world of school. Although the boys and girls initially share their parents’ discomfort and insist on X’s acting like one sex or another, they eventually envy and then imitate its freedom in dress and play. Finally the angry parents of the other children demand that X be examined physically and mentally by a team of experts.

If X’s test showed it was a boy, it would have to start obeying all the boys’ rules. If it proved to be a girl, X would have to obey all the girls’ rules.

And if X turned out to be some kind of mixed-up misfit, then X must be Xpelled from school. Immediately! And a new rule must be passed, so that no little Xes would ever come to school again.

Of course, X turns out to be the “least mixed-up child” ever examined by the experts. X knows what it is, and “by the time X’s sex matters, it won’t be a secret anymore.” Happy ending!13

In an instance of science imitating art, “X: A Fabulous Child’s Story” inspired a series of real-life studies that explored the relationship between an infant’s sex (real or assumed) and the child’s interactions with adults. The earliest published study was 1975’s “Baby X: The Effect of Gender Labels on Adult Responses to Infants,” by Carol Seavy, Phyllis Katz, and Sue Rosenberg Zalk. In the experiment a baby dressed in a yellow jumpsuit was presented to adult subjects with instructions to play with the baby, choosing a football, a rag doll, or a flexible plastic ring. The technician running the study was under instructions to give no clues as to the sex of the baby. Subsequent studies became progressively complex. Sometimes the baby’s assumed sex was the variable, with the same infant given different names (Beth or Adam) and dressed in pink or blue, accordingly.14 Other studies explored when and how well children learned gender stereotypes or how adults’ use of these clues may or may not reveal their own beliefs about sex, gender, and appropriate behavior. Baby X research even trickled down to elementary school science fairs; two sixth-graders from my suburban Maryland neighborhood entered a project based on a trip to the local mall with a baby they dressed first in boys’ clothes and then girls’ and then recorded shoppers’ responses to each variation.

What we’ve learned from all of these studies is that children understand and can apply gender stereotypes well before they reach their third birthday. These studies also confirmed the belief that adults routinely look for and use gender clues in their social interactions with babies and toddlers, unconsciously communicating gender stereotypes at the same time. These “Baby X” studies, combined with the emerging narratives in popular works such as the children’s version of “X,”15 William’s Doll, Free to Be . . . You and Me, and Sesame Street, helped reinforce the feminist message that gender stereotyping was harmful to children.

One of the more subtle themes in Gould’s story is the unequal value of feminine and masculine traits. Given that her essential message is that children should be free of stereotyped behaviors and treatment, she was surprisingly dismissive of some feminine markers. For example, the Official Instruction Manual mentioned in the story offers the following directions for interacting with their new baby: “plenty of bouncing and cuddling, both. X ought to be strong and sweet and active. Forget about dainty altogether” (emphasis in the original). This ambivalence, if not hostility, toward femininity is an important part of the cultural climate of the early 1970s.

Gould also draws a picture of clothing and toy stores that is not entirely accurate. In the story the parents are faced with a highly gender-binary landscape that sounds more like 2012 than 1972, with sharply distinctive boy and girl sections in the store. In reality, clothing and playthings for babies and toddlers a generation ago included many more neutral options than are available today. So X is provided not with neutral things that actually existed at the time, but instead a selectively androgynous blend of “blue pajamas in the Boys’ Department and cheerful flowered underwear in the Girls’ Department.” In reality a baby in 1972 could have worn both blue pajamas and underwear in a floral print (Sears’ Winnie-the-Pooh nursery print had Pooh, Eeyore, Piglet, and flowers), and they would have been considered neutral! Gould also invents fantastic, gender-bending toys and books, such as a boy doll that cries “Pa-Pa.” X’s favorite doll is a robot programmed to bake brownies and clean the kitchen. When the other children decide that X is not weird, but cool, the message they get is that by playing with both boys’ and girls’ stuff, X is “having twice as much fun as we are.”

Finally, when the children decide to go to X’s house to play, they are all shown in identical red-checked overalls. “X: A Fabulous Child’s Story” tells us that some stereotypically feminine traits (daintiness) are undesirable, that children naturally desire both “boys’” and “girls’” things, and that the ultimate form of gender neutrality is uniformity with a masculine tilt. The X model of a “gender-neutral” world was masculine, like most of the unisex trend, with occasional touches of femininity to help boys be more nurturing and expressive. This aligns with much of the feminist opinion about dress in the late 1960s and ’70s, which cast traditional women’s clothing as limiting, objectifying, and disempowering while portraying men’s clothing, especially pants, as symbolically empowering rather than just more practical.

This fictional child and its scientific counterparts provided support and evidence for the cultural and social origins of gender roles, framing the “nature or nurture” debate in a manner that has provoked discussion in living rooms and conference rooms ever since. Evidence of this discussion can be found in popular magazines, often drawing on emerging (and contradictory) scientific opinion. A lengthy article in Newsweek in 1974 asked “Do Children Need Sex ‘Roles’?” and offered pro and con opinions from the psychiatric community.16 Psychiatrists advocating traditional gender roles argued that children were the victims of “militant women’s liberationists, overachieving fathers and . . . androgynous youth culture,” and warned that unisex child raising would lead to more sexually aggressive girls and more passive boys. Such a reversal would also result in a greater incidence of homosexuality, they hinted, clearly based on antiquated notions of the “causes” of same-sex attraction and the continuing belief that it was a mental illness, despite the recent change in the American Psychological Association’s (APA) official position. On the side of ungendered parenting were professionals who charged that the profession had long been in error when trying to adjust people to “the cultural status quo” rather than question the status quo itself. They also came armed with clinical experience and scientific research: psychologist Jeanne Humphrey Block offered evidence from her prizewinning research that adults who are raised to assume traditional roles are less satisfied with themselves. If the cultural roles were unhealthy or damaging—and subject to change—why not change them? The battling experts did agree on one point: it was fine to give baseball mitts to little girls and dolls to boys in early childhood, as long as it wasn’t part of an agenda to “destroy the child’s basic biological identity,” but children needed to arrive at a stable gender identity by the time they started school.17

The elephant in the room in many of these discussions was homosexuality, specifically the treatment of boys who exhibited signs of femininity. Not surprisingly, the scholarly literature addressed these issues much more directly than the popular books and articles, although Psychology Today and similar popular science magazines occasionally helped bring these studies to the larger audience. Reporting on the work of the Gender Identity Project at the University of California at Los Angeles in 1979, Psychology Today asked, “Does a boy have the right to be effeminate?” The clinical psychologists at UCLA had published an article on their work in helping “gender-disturbed” children (mostly effeminate boys, since being a tomboy created fewer social problems for girls) learn more androgynous gestures and speech. In this article, as in the Newsweek piece, the clinicians were pitted against the more theoretical psychologists, who opposed these interventions, which they felt sent negative messages to the boys about themselves and amounted to efforts to cure or prevent homosexuality. Ever since the 1973 APA reclassification of homosexuality, treating it in children was bound to be controversial. The UCLA team defended their work as not being aimed at preventing homosexuality, but helping children fit into their social environment. Once more the argument boiled down to whether the person or the culture needed to be fixed.18

By the late 1970s claims that gender was almost entirely a matter of nurture were being taken seriously by a wider public, but with surprising results. Useful as the concept of gender as separable from sex is, it introduced a messy new variable into popular notions about sex and sexuality. The idea that gendered behaviors are entirely cultural could be used by both feminists and antifeminists. For many conservatives and antifeminists, biological essentialism (biology is destiny) was replaced by cultural chauvinism: yes, gender roles are cultural, but the traditional (Western, Judeo-Christian, middle-class—take your pick) cultural norms are superior and should be preserved. If gender could be taught that still begged the question of which gender rules should be passed along to the young.

The most progressive parenting literature frequently advocated “unisex child raising,” applying the fashion term in a brand-new way. Unisex child raising included encouraging children to play with a variety of toys, modeling gender-free roles as adults by switching chores (Daddy cooks, Mommy mows the lawn), and choosing neutral clothing and hairstyles for the whole family. Public education also took a decidedly liberal position on gender stereotyping, promoting curricula and resources including a widespread adoption of Free to Be . . . You and Me for primary grades. A two-year study of gender stereotype “interventions” at a variety of grade levels convinced Marcia Guttentag and Helen Bray that undoing cultural training was possible, and they clearly believed that it was desirable. They were hardly radical in their advocacy; their goal was to “expand job and human opportunities” for boys and girls.19 Yet it is easy to see how this agenda would have seemed offensive and even threatening to parents and educators who believed in the moral rightness of traditional cultural norms.

For children’s clothing, unisex essentially meant more a wider range of colors, styles, and decoration for boys; fewer very feminine styles for girls; and more neutral choices for all. On the surface this was identical to trends for teenagers and adults, but the difference is in the effect. From tot lot to retirement we are engaged in a continual process of adjusting our appearance according to our inner sense of self and the accepted patterns of identity expression. Children engage in the process at the same time they are first acquiring identity, which, I suspect, makes a huge difference.

Children’s fashions of the early 1970s demand our attention with their bright colors and gender-defying styling. In some of these old pictures it really is impossible to tell the boys from the girls. For young children not yet in school, unisex fashions combined more neutral styles and a trickling down of adult fashions. As with clothing for newborns, pastels were rejected in girls’ clothing in favor of earth tones and bright primary colors. But a broader and deeper view reveals patterns that continued to follow old, established rules. Some of the “paradigm shifts” turned out to be mere fads. In the end unisex children’s fashion enjoyed a very brief popularity and somehow also ushered in an era when juvenile styles from babyhood on were more gendered than they had been in the early 1960s.

Girls’ clothing, beginning in the mid-1970s, began to regain feminine details that had been briefly discarded: ruffles, lace, puffed sleeves, and pastels. Yes, girls could wear pants to school, but pants were no longer perceived as exclusively masculine, and girls’ styles featured the same dainty and fussy details as girls’ dresses did. Consumers, parents and girls alike, who preferred plainer, more tailored styles found fewer and fewer options beginning in the mid-1980s. The plain T-shirts, overalls, and pajamas for children that once occupied several pages in the Sears catalog were reduced first to just a page or two and then to nothing except for a few yellow or green outfits for newborns. Boys’ brief flirtation with color and pattern ended along with the peacock revolution, replaced by athletic styles, the preppy look, and camouflage. This time not even the tiniest babies escaped gender labeling; prenatal ultrasounds made it possible for parents to furnish them with a completely gendered environment from the very start. It was as if a switch had been pulled and gender ambiguity in babies disappeared completely.

Of course for most children born after the mid-1980s this hyper-gendered world was traditional—the way things had always been. Although it is clear that our cultural landscape is subject to change, we tend to see the world we knew at four or five as the way it always was, even when we learn it was not. A little girl born in the late ’60s probably grew up wearing pants to school. Even if she learns that for generations this had been absolutely forbidden, she will never share the sense of rebellion and defiance her mother experienced when she wore jeans or a pantsuit in 1970. This sense of history colors what adults perceive as traditional, even when that “tradition” dates only to their infancy. They’ll look back at the clothing of their childhood and reassess those fashions through the lens of their own personal tastes and experiences. One woman may look at her grade-school class picture and feel nostalgia for plaid dresses; another remembers only cold knees. The boy with the gender-free wardrobe in the early 1970s may later recall the embarrassment of being called a girl; another may miss the bright colors and patterns.

Unisex fashion played out differently for children than for grown-ups. On adult bodies unisex clothing can accentuate physical differences, creating a pleasant sexual tension. Babies and preadolescent children often don’t look masculine or feminine, and dressing them in ambiguous clothing produces social discomfort. In a culture where “boy or girl?” determines our mode of address and interaction, an encounter with the unknown is fraught with anxiety for the onlooker. For children between three and six—old enough to know their own sex but not yet secure in its permanence—being mistaken for the wrong sex can be embarrassing or even frightening.

While the battle over the proper roles for men and women raged in the popular media throughout the 1970s, parents were left to clothe and raise their children with no clear agreement and confusing advice from the “experts.” The only common theme in the advice literature was the assertion that the stakes were very high; children’s future mental health and happiness were at stake. One thing is clear: people on both sides of the controversy seemed to agree on the tremendous power of the gender-shaping abilities of clothing. Feminist writers argued that traditional gendered clothing would make children repressed, rebellious, and unable to function in the new egalitarian society. More conservative voices warned that blurring the distinction between the sexes would confuse children, possibly even steer them into homosexuality.20

Future historians tracing the emergence of the American “culture wars” may not bother to look at children’s clothing, but they should. A longitudinal study of two hundred “conventional and unconventional” families beginning in 1974 identified a cluster of attitudes and behaviors in a subset of unconventional households the researchers labeled as “pronaturalism”—a preference for natural/organic food and other materials, emotionally expressive men, low-conflict parent-child relationships—that set them apart from, and often at odds with, more conventional parents.21 For a brief time in the 1970s, pronaturalist parents found their beliefs positively portrayed in the media and supported by public education and policy, or at least not deprecated. This changed with the emergence of the modern conservative movement and the “moral majority,” which dominated both culture and politics in the 1980s.

While the multitudes of clinical studies offered no satisfactory answer to the question of why some people are homosexual while others are not, parents attempting gender-free child rearing found their efforts resisted by their own children. Even advocates of nonsexist child rearing noted the stubborn persistence of sexist behaviors and beliefs. Consistent with their own conviction that gender was a product of nurture, they tended to place the blame on media and consumer culture, dismissing the possibility that daughters’ rejection of trucks and longing for frilly dresses had any basis in biology.22 But many parents, faced with rebellion, felt like Jesse Ellison’s mother, quoted in a 2010 article: “We all thought that the differences had to do with how you were brought up in a sexist culture, and if you gave children the same chances, it would equalize. . . . It took a while to think, ‘Maybe men and women really are different from each other, and they’re both equally valuable.’”23

In a 1981 journal article researcher Penny Burge reported that in her survey most parents supported nontraditional sex-role attitudes and practices.24 But this does not represent every parent. Just because Free to Be . . . You and Me won awards and sold millions of records, books, and videotapes does not mean its message won universal approval. A parent who read Psychology Today, Ms., Parents, McCall’s, or Good Housekeeping—or who even talked with other parents—would likely be familiar with the arguments for nonsexist child raising and unisex clothing but not necessarily persuaded by them. Feminists used the cultural construction of gender to push back on the claim that women had a natural inclination toward home and family. Conservative parents generally rejected unisex child raising along with other elements of feminist ideology, while less ideologically driven parents simply found gender-free clothing less appealing. Both categories of parents certainly had access to clothing choices other than gender-free throughout the era. Sears might not offer pastel toddler clothing, but specialty stores did, and in the 1970s many women still knew how to sew, which gave them even more options. And popular culture is complex and often contradictory: at the same time that girls were being encouraged to wear simple, modern styles, the television series Little House on the Prairie (1974–1982) and the nation’s bicentennial celebrations popularized and romanticized versions of historical girls’ dresses and women’s traditional roles.

Nonsexist child rearing, and with it unisex clothing for children, was supposed to transform our culture by limiting children’s exposure to stereotypes and preventing their acquisition of limited gender roles. Firm in their belief that gendered behaviors stemmed from nurture, not nature, progressive parents and educators launched a movement to reprogram boys and girls from birth to be completely free to express their “natural” selves. Much to their surprise, for many children their “natural selves” fell short of the egalitarian ideal. Unfortunately, all we have today with which to judge the success or failure of the unisex movement is anecdotes and subsequent history.

The anecdotes tell of failure after failure. My own son (born in 1986), as a toddler, used to bite his slice of cheese into the shape of a gun. Girls rejected trains and trucks and demanded Barbie dolls and nail polish. The stories go on and on. Are these behaviors really evidence that gender-free child rearing is a wasted effort, or do they suggest that gender is more complicated than originally thought? From the highly gendered vantage point of the early twenty-first-century children’s clothing department, kids’ unisex styles of the 1970s seem just a small blip in the steady transformation of infants and toddler clothing from ungendered to a nearly complete masculine/feminine binary. Yet that brief period has had lasting effects, including some unsettled issues that still vex us.

Not everyone follows fashion trends, but it is safe to say that unisex clothing options represented a controversial issue that thoughtful parents could not help but be aware of, even if they chose to disagree. Most of the unfinished business of unisex childrearing settled on the children of the 1970s, not their parents. Children, too, remember the clothing and their own reactions and preferences, and even if they rejected the gender ambiguity of the fashions, they absorbed the egalitarian messages of the unisex movement. Young women in the late 1980s and 1990s expressed a desire to “have it all,” not just in terms of career and family but also in terms of feeling pride in feeling female. This was not a simple matter to translate into actions. For example, no parents thought about sexual assertiveness when they encouraged their daughters to be less “dainty,” but by the late 1980s the popular media was bemoaning the sexualization of girls in their early teens. Was this the result of feminist influence and a sexually permissive culture, or an expression of young adolescent girls’ real nature, unencumbered by “old-fashioned” notions of feminine delicacy?

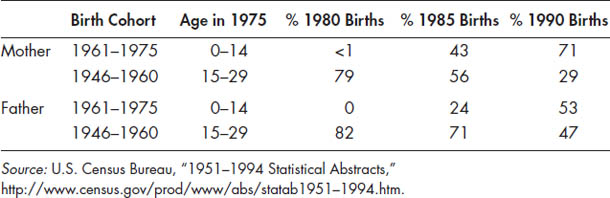

Table 4.1. Birth Cohort of First-time Parents, 1980–1990

One possible explanation for this shift is demographics. Between 1980 and 1990 the majority proportion of births to first-time parents shifted from baby boomers (b. 1946–1964) to Generation Xers (b. 1965–1982). This generational perspective matters because of the huge difference between being a twenty-three-year-old choosing gender-bending clothing for herself or himself in 1975 and having unisex clothing selected for you as a three-year-old. This suggests that the children of the ’70s became parents who were likely to prefer gendered clothing for their own offspring.

Even more striking, as the children of the 1970s became parents, they demanded even more stereotyped clothing and toys for their offspring than had existed in their childhood. Superficially, the explanatory pendulum seemed to have swung back toward “nature,” because this gender revival was justified as satisfying children’s innate preferences, with the anecdotal unisex failures providing the necessary proof. Yet the same parents placed no limits on their daughters’ ambitions; like their mothers, young girls seemed destined to have it all: girly clothes, spa parties, and soccer—with pink uniforms. Add to this equation the advent of prenatal testing that revealed the baby’s sex months before birth. Knowing only that fact about their unborn child, new parents seemed eager to embrace “traditional” gender in their preferences for clothing and nursery décor. Many of my baby boom sisters were horrified.

Something even more troubling has shown up in girls’ clothing since the revival of feminine designs: women’s clothing of the 1960s that essentially conflates femininity, youth, and sexual attractiveness has trickled down to girls’ clothing, first for young teens, then to the 7–14 size range, and eventually even younger. It is not so jarring to see skimpy clothes and flirty models in the Juniors section; it seems completely consistent with the spirit of fashion trends since the 1960s. But seeing seven-year-olds in bikinis, posing like beach bunnies, while in the same spirit, seems inappropriate to many adults. The modern controversies over sexy dressing in child pageants and the KGOY (kids getting older younger) trend have their roots in the sexual and gender revolutions of the 1960s.

Part of the appeal of adult unisex fashion was the sexy contrast between the wearer and the clothes, which actually called attention to the male or female body. A grown man in a brilliant pink sports coat can still appear very masculine, even with a long haircut, because his voice, body shape, and gestures also convey gender. If he sported sideburns and other facial hair, the contradiction between “feminine” clothing and “masculine” physique actually created the desired tension and novelty. Similarly, women in pants appearing in popular humor were usually depicted as more attractive because of the way that trousers emphasized their curves. Ironically, unisex fashions for adults did not really blur the differences between men and women, but instead highlighted them.

One significant tie to previous patterns was a continued distinction between clothing for very young children and adult clothing. Toddler boys enjoyed a greater range of colors and patterns than older boys and men, and toddler girl fashions were shorter and more whimsically decorated than those for older girls and women. Above the toddler age range, however, age markers were blurred. It was not just existing gender rules that broke down during the 1960s; older conventions about what was age-appropriate also crumbled. What had once been clear distinctions according to age became a much looser and more permeable set of options. One sign was a more juvenile turn to teenagers’ casual clothing, which became more colorful and playful. Minidresses on young women made them look like little girls, and the men’s hairstyles and collarless jackets popularized by the Beatles were strongly reminiscent of toddler boys’ classic Eton suits and long bangs. Through most of the 1960s unisex design was seen more in toddler clothing than in infants’ wear as adult styles mimicked children’s, which in turn reflected prevailing adult trends. This mutual influence resulted in adult clothing that was youthful and androgynous and children’s clothing that looked “sophisticated” because of its resemblance to adult fashions.

This trend prompted considerable discussion in the style press. Fashion writers and cultural critics noted the “little girl” trend for women’s clothing with some confusion. Was it asexual because it was immature, or was it super-sexy because of a “Lolita” effect, mimicking schoolgirl-themed pornography? There was no attention at the time to the implications for little girls wearing the same styles, but from a twenty-first-century vantage point, one can see the first outlines of early childhood sexualization in the baby doll dresses of young women.

It is worth considering that the relationship between girls’ play clothes and fashions for teens and adult women was not simply one of trickling down, but was also a result of “carrying over” childhood clothing as girls grew to women. For example, jeans and overalls had been part of girls’ playtime wardrobes for decades, and teenagers had been exchanging their skirts for dungarees after school since the 1940s. As rules of dress etiquette were discarded in the early ’60s—no more hats or white gloves—and lifestyles became more laid-back, jeans and other casual trouser styles increased in popularity among young adults. Or to look at it from a different perspective, children who had grown up in jeans and T-shirts in postwar America saw no reason to stop wearing them just because they had outgrown the playground.

In recent years scholars and popular authors have once more challenged the notion that masculinity and femininity are innate; they are also attempting to highlight the roles of media and consumer culture in defining and promulgating gender stereotypes. Despite their efforts, however, the issue seems no closer to being settled than it ever was. Every few months there is a new story about a boy who dresses like a girl, a girl who dresses like a boy, or a boy who likes pink nail polish that sets off a new round of claims, counterclaims, and controversy.25 Around the globe, parents attempting to raise ungendered children make the headlines, and their stories echo the messages of the unisex era.26 Nearly always the public reaction is mostly reminiscent of the adults in “X: A Fabulous Child’s Story”: anger, derision, and warnings of future confusion. But they also have their defenders, many of them parents of the same generation: the ones who grew up highly gendered in the 1980s and who are rejecting the binary and looking for new alternatives.

So is gender identity an effect of nature or nurture? Science tells us that the foundations for sexual behavior are laid down before we are born and also that human variation is vast and complex. Knowing that most boys behave in a particular way does not tell you how your son will behave, nor will it explain why your daughter might prefer Barbies or Transformers. The dominant professional advice for parents of gender-fluid or gender-creative children is to watch and wait; sometimes it’s a phase and sometimes it isn’t, and interventions with the goal of “correction” do more harm than good. History tells us that children can wear dresses or pants, and can wear pink or blue or both together, but that strongly gendered or gender-free clothing has an unpredictable effect, most of it not evident until they are grown. The clearest answer, for now, to the age-old question is nature and nurture, sympathetically, unpredictably.