Litigating the Revolution |

5 |

Fashion has had a legal side for centuries. Powerful rulers once set limits on who could or could not wear certain finery and decreed that colors, badges, or hats be used to set certain groups of people apart as “others”—Jews, for example, who were required to wear yellow badges or pointed hats in parts of thirteenth-century Europe.1 The umbrella term for these edicts is “sumptuary laws”; one of my favorites, from medieval Spain, begins with “the king may wear anything he wishes.” Sumptuary laws reveal a great deal about a society—for example, which goods are highly valued (and therefore reserved for the élites) and also which groups may be considered a threat to the status quo. Amid the social turbulence of the Renaissance, wealthy merchants and their wives were often singled out as needing to be reminded of their inferiority to their high-born betters. Economist Thorstein Veblen observed in 1899 that in modern capitalism, wealth could be freely displayed by nearly everyone who has it, as a sign of socioeconomic superiority. But we still face restrictions in the form of dress codes, usually in schools or in the workplace, that attempt to enforce a uniform appearance or suppress potentially disruptive elements. These modern regulations have elements of social class (public schools with uniform dress codes tend to be in poorer districts), race (local ordinances against “saggy pants”), or gender (laws against cross-dressing and public indecency, dress codes that enforce gender stereotypes). Sumptuary laws don’t come from out of the blue: they are a reaction by the powerful to undesirable behavior from their “inferiors.” The rampant and dramatic changes in gender expression that emerged in the 1960s met with just such resistance, leading in some cases to the courtroom and sometimes even to prison. The litigious heat generated by long hair, short skirts, and women in pants is strong evidence that these were far from trivial issues for the parties involved. The fact that we are still arguing about the same principles, though in different clothing, is part of the ongoing legacy of the 1960s.

In nearly every case the defendants in these legal cases were what young people at the time would have labeled “the Establishment”: school administrations, employers, or the military. The plaintiffs were arguing from their less powerful positions as students, employees, or simply as individuals (men, women, minors, people of color). Each of these variables carries with it distinct arguments on the part of both the plaintiffs and defendants. Although the prohibition of pants for women and long hair for men is often mentioned in tandem, the two situations could not have been more different. Court cases involving male plaintiffs dominate the legal record. There were seventy-eight court decisions at the state level or higher about long hair in the United States between 1965 and 1978, compared with just six cases about girls or women wearing trousers. Longhaired boys and men experienced harassment and even violence, while women and girls wearing slacks or jeans might just be turned away from a restaurant or sent home from school to change outfits. Between the first court case concerning pants, in 1969, to the last, in 1973, trousers for women went from being a novelty to a wardrobe staple with a minimum of public outrage.

Chronologically, the legal record begins in 1964 with lawsuits involving minors challenging school dress codes: first longhaired boys and later both boys and girls with a more extensive list of complaints. In the 1970s there was an increase in the number of cases brought by adults concerning workplace restrictions. The legal arguments on both sides shifted over time as well.

For men and boys perhaps the most contentious and visible aspect of unisex fashion concerned not clothing, but hair. The British Invasion in popular music deserves much of the credit for the early trend toward longer hair for men. The long hair craze swept the United Kingdom before it arrived on American shores, propelled at first by the Beatles and soon after by scruffier groups like the Rolling Stones. None had originated the style; art school students such as John Lennon, Paul McCartney, and Mick Jagger had been sporting long hair for some time. The unisex effect was accentuated when British girls began adopting the same styles in the summer of 1964, either in imitation of the rock stars or to present a “his and hers” appearance when they were out with their boyfriends. There were skirmishes over long hair in schools, but overall the public reaction in the U.K. was nonchalant, with most people considering it as just another adolescent fad. Noting that long hair used to be associated with the upper class and close-cropped hair with the middle and lower class, adolescent psychologist Derek Miller pointed out that British teens were just bored and trying to stand out and that long hair was preferable to juvenile delinquency.2 Mick Jagger of the Rolling Stones detected the moral panic behind some of the criticism: “They seem to have a sort of personal anxiety because we are getting away with something they never dared to do. It’s a personal, sexual, vain thing. They’ve been taught that being masculine means looking clean cropped and ugly.”3

Beginning in 1963, newspapers in the United States reported numerous instances of boys, some as young as nine, being barred from school for having long hair. Most of these confrontations ended with a quick trim. In a parochial school in New Hampshire, the administrator actually loaded eighteen students on a school bus and delivered them to a local barber. A smaller group of students defied the rules and ended up facing school or district hearings. The well-publicized story of fifteen-year-old Edward T. Kores Jr. of Westbrook, Connecticut, ended with Kores transferring to a private school after he lost his appeal to the state education commission. His father, a carpenter, at first vowed to “fight this in the court,” but the family eventually decided against that course of action.4

The trouble escalated in fall 1964 when boys started showing up at school with a summer’s growth of hair. It would seem that most school systems were caught unaware, without a true dress code, just vague guidelines about neatness. Newspaper accounts of similar events started popping up across the country. Most cases were resolved with a quick trip to the barber or brushing the boy’s bangs off his forehead. But eventually a few ended up in local courts. Perhaps the significant detail to note about these cases is that because the boys were minors they had to have the support of their parents in order to take it to the legal level.

The number of hair resisters who took the next step—suing the schools in state-level courts—was smaller still. The earliest such case involving hair was Leonard v. School Committee of Attleboro (Massachusetts), which began with the first day of classes on September 9, 1964, and went all the way to the state supreme court, which upheld the school’s right to dictate the appearance of students. George Leonard, already a professional musician performing under the name Georgie Porgie, had argued that the school did not have a written dress code and that his long hair was vital to his career, but the court ruled that the principal had the authority to tell Leonard to get a haircut and to expel him if he refused. When he attended an Attleboro High School all-class reunion in 2013, he was greeted as a celebrity; to his classmates and the younger students at the school, he had been a hero.5 To some fans of freedom of expression, he still is: his entry at the Rhode Island Music Hall of Fame website claims, “Every kid who sports long hair, pink hair or a shaved head, or wears a nose ring, a tattoo or makeup, owes his right to do so to” the Pawtucket-born Leonard.6 Georgie Porgie and his band appeared at least once with the Cape Cod garage band the Barbarians, who recorded the 1965 hit “Are You a Boy or Are You a Girl,” the unofficial anthem of the long hair cause.

Are you a boy

Or are you a girl

With your long blonde hair

You look like a girl (yeah)

You may be a boy

You look like a girl

You’re either a girl

Or you come from Liverpool

(Yeah, Liverpool)

You can dog like a female monkey

But you swim like a stone

(Yeah, a rolling stone)

You may be a boy (hey)

You look like a girl (hey)

You’re always wearing skin tight

Pants and boys wear pants

But in your skin tight pants

You look like a girl7

Signs that this was a more serious issue appeared almost immediately. The New York Civil Liberties Union went to the defense of high school boys with long hair in 1966, releasing a statement saying that dress codes disapproving of hairstyles were violating constitutional guarantees by punishing “nonconformity and expression of individuality.” That same year the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) wrote letters and memoranda to principals in three Philadelphia-area high schools asking them to rescind bans against hairstyles on the grounds that public schools have no authority to impose such regulations. The boys in two of the schools had directly appealed to the ACLU for help.8 In 1968 the ACLU issued recommendations regarding the academic freedom of secondary-school students and teachers. The twenty-two-page policy statement was six years in the making and included the following student rights:

To organize political groups, hold assemblies and demonstrations, wear buttons and armbands with slogans as long as these do not disrupt classes or the peace of the school

To receive formal hearings, written charges, and a right to appeal any serious violation conduct or charge

To dress or wear one’s hair as one pleases and to attend school while married or pregnant unless these things “in fact” disrupt the educational process

To publish and distribute student materials without prohibitions on content unless they “clearly and imminently” disrupt or are libelous

The authors of the statement argued that school administrators had often erred on the side of the need for order rather than the need for freedom in establishing and enforcing school rules. Titled “Academic Freedom in the Secondary Schools,” the statement was distributed in booklet form to all major education associations and available from all state ACLU affiliates.9

Dress code cases were working their way through the courts just as quickly, often with the assistance of ACLU attorneys. The first such case reached the U.S. Supreme Court in 1966, but the court refused to hear it. Three adult male students from the Richmond Professional Institute (RPI; now Virginia Commonwealth University) had brought the case, which involved an administrator requiring them to shave their facial hair and get haircuts before they could register for classes. The plaintiffs—Norman Thomas Marshall, Robert D. Shoffner, and Salvatore Federico—claimed RPI was denying them the rights of self-expression and to be left alone and insisted that the consequence, being barred from registration, was cruel and unusual punishment. The circuit court judge had ruled against them, finding the rule “reasonable and in no sense arbitrary” and necessary for the “preservation of discipline.”10

School administrators in many states had followed this case, as evidenced by the official comment about it from the High School Principals Association in New York: “The court statement to the effect that the question is one to be determined by common sense rather than by courts and [that] schools obviously have the authority to make rules on the matter express the views which we hope will now be adopted by our own superintendent of schools.”11 This last comment was a poke at Dr. Bernard Donovan, superintendent of schools in New York City, who, in the view of the principals association, had not only failed to support principals’ efforts to nip longhaired defiance in the bud but had also interfered with local authorities by stepping in on a case involving two students at Forest Hills High School in Queens.12 The sixteen-year-olds had been confined to the dean’s office during the school day for two weeks, and the New York branch of the ACLU had lodged a protest with the New York State superintendent of schools, who had not yet responded. Donovan had ordered principal Paul Balser to let the boys attend classes in the meantime, and the result was an immediate avalanche of protest from teachers and the parents’ association. Students interviewed by the New York Times had different views, however, ranging from disinterested (“It’s just a fad”) to defiant (“I don’t think they had the authority to tell you to get a haircut”). In an article in New York State Education (the teachers association journal), Donovan had condemned “punitive action” in dress code cases, giving the example of one principal who was standing at the school’s door with scissors, trimming hair. The tempest swiftly escalated, as the High School Principals Association sent a defiant letter to Donovan saying that in the absence of a policy from his office, they would construe his actions as applying only to Forest Hills High School. In the meantime they intended to “continue to maintain the kind of safety, dress and appearance regulations that will make our students presentable, teachable and employable.”13 In this and in similar cases all across the country, the Supreme Court’s refusal to render a decision seems to have to complicated the question and only keyed up the controversy.

Not everyone over the age of eighteen agreed with dress code defenders. A sharp-eyed reader responded to the principals’ statement with a letter to the editor of the New York Times that expressed the opposing view, one held by many parents and teachers: “I and some others interested in education and in doing things the American Way have discussed the situation in your city as elsewhere and have felt that Dr. Donovan rather than those principals which, given such exhibitions of their ‘up the down staircase’ mentalities, has acted to preserve common sense.”14 “Up the down staircase” is a reference to a best-selling memoir of a first-year teacher’s experiences in a New York City school overseen by an overzealous administrative assistant the author calls “Admiral Ass.” The battle lines in the culture wars were taking shape.

Most school and workplace conflicts over appearance were resolved without going to court, of course. A principal might warn dozens of longhaired boys that they faced suspension, and all or most would head to the barbershop, albeit reluctantly. Only a small minority of students, and their parents, chose to challenge dress codes legally. Still, the result was that nearly eighty such cases moved through the nation’s courtrooms between 1965 and 1978, thirty-five resolved at the federal district level and twenty at the appellate level, landing in every federal circuit except the second. Eleven such cases applied to the U.S. Supreme Court, but all were denied certiorari, with the result that the varying judgments in the lower courts established the legal precedent in each state.

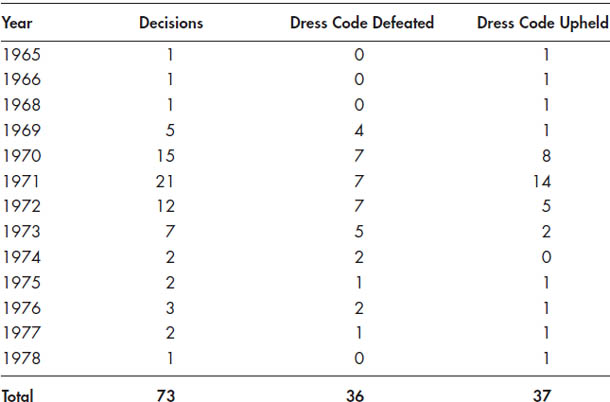

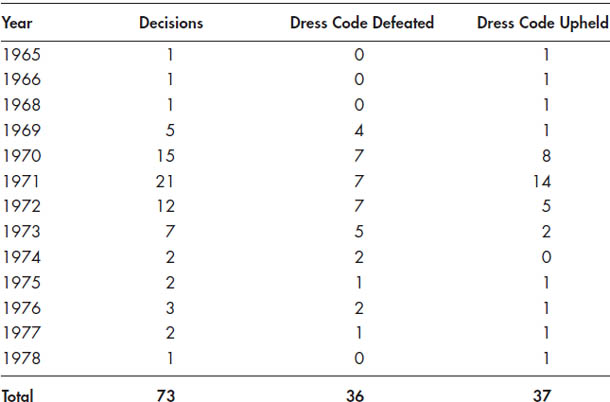

There were seventy-three long hair cases from schools or colleges decided by the courts between 1965 and 1978, (there were also workplace cases, which will be discussed separately); two-thirds of those were decided between 1970 and 1972. Frustratingly for all concerned, however, there was no clear trend in the decisions (see table 1). By the mid-1970s dress code fatigue was setting in. Some schools gave up. Teachers complained that dress code enforcement itself was more disruptive than long hair or girls wearing slacks. In some cases coaches and sponsors of extracurricular activities tried to make short hair a requirement for boys’ participation, but those rules, too, often proved controversial and, in the long run, unenforceable. In the end neither side won the legal battle, yet both claimed a sort of victory. Long hair cases fell off because long hairstyles became widely acceptable in mainstream culture, which was a kind of vindication for the advocates of the more liberal position. But the Supreme Court had clearly left the authority for dress codes with the states and the local school systems, so a great variety of rules persisted and dress code controversies have never completely subsided. A map of the states where dress codes were upheld in the majority of cases neatly overlays the maps of opinion on many other cultural issues. At the extremes the states within the jurisdiction of the Fifth Circuit (Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas) upheld the schools’ position in twelve out of fourteen cases. In contrast, the Second Circuit (Vermont, Connecticut, and New York) had only three dress code cases between 1965 and 1978 and ruled in favor of the students every time.

Plaintiffs in the long hair cases of the 1960s claimed that school dress codes violated their constitutional rights, citing the First and Fourteenth Amendments most frequently. Their First Amendment argument was that one’s appearance was protected speech. Dress codes that applied differently to students and adults, or to girls and boys, violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Other cases pointed to protections of the Third, Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, Eighth, Ninth, and Tenth Amendments. There appears to be no consistent pattern of the success or failure of these various arguments over the entire period, but students and their families found encouragement in the case of Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969), where the Supreme Court had ruled 7–2 that minor students enjoyed constitutional protections, including First Amendment rights.15 However, the Tinker case involved the banning of black armbands, which students wore to protest the Vietnam War, not school dress codes. Justice Abe Fortas, writing the majority opinion, was careful and clear to point out: “The problem posed by the present case does not relate to regulation of the length of skirts or the type of clothing, to hair style, or deportment.” His use of the phrase “the present case” left open the possibility that such regulations might also face a constitutional test. Justice Hugo Black, in his dissent, worried that “if the time has come when pupils of state-supported schools, kindergartens, grammar schools, or high schools, can defy and flout orders of school officials to keep their minds on their own schoolwork, it is the beginning of a new revolutionary era of permissiveness in this country fostered by the judiciary.”

Table 5.1. Court Decisions in School Long Hair Cases, 1965–1978

Tinker v. Des Moines did not open the door to riots in the schools, but it did open the floodgates on dress code cases. Students, their families, and attorneys saw an opportunity to broaden the narrow ruling, and administrators and school boards saw in the majority opinion some additional justification for school rules. The justices had agreed that freedom of speech was not unlimited and could be restricted out of concern for public safety or serious disruption. With this clearly in mind, dress code defenders increasingly cited the need to avoid “disruption” in their schools as a reason why outlandish or unusual hairstyles and clothing should be banned. The nature of these alleged disruptions ranged from amusing to disturbing. Teachers testified that the longhaired students distracted their classmates by “primping” or “flipping their hair.” There were also numerous accounts of violent encounters between “shorthairs” and “longhairs,” which are similar to the forced haircut story that surfaced during the 2012 presidential campaign, in which a teenage Mitt Romney and a few friends had pinned down a longhaired classmate and cut his hair.16 In nearly all of the examples of violent disruption, the shorthaired students were the aggressors and the schools had failed to discipline students who harassed longhaired classmates. In a few cases they found that teachers had initiated the harassment by singling out longhaired students for criticism. Rather than punishing the harassed students, one judge noted, “We are inclined to think that faculty leadership in promoting and enforcing an attitude of tolerance rather than one of suppression or derision would obviate the relatively minor disruptions which have occurred.”17

It was not just the rationales in the court decisions that were confusing the issue: the many defendants, plaintiffs, and witnesses expressed the multitude of reactions people experienced with regard to long hair. The courts also raised the question of whether the rules themselves were a source of disruption:

It is contended that disruption is caused by the very fact of disobedience to a school rule, whatever the content of the rule may be. If so, this consideration lends no support to the necessity for, or the rationality of, the rule itself. If the rule itself is unnecessary, those who promulgate it must accept the consequences of its violation.18

There is some uncertainty in our minds as to whether problems of behavior and discipline necessitated the dress code or whether the enforcement of the dress code merely contributed to the problems of behavior and discipline.19

This belief was underscored in Independent School District v. Swanson (1976) by the testimony an administrator from neighboring district who testified that his own district had abandoned dress codes because enforcement efforts had reduced schools to a “police state,” which was disruptive to education.20

Another argument that was popular with the school boards was the connection between long hair and other negative behaviors. The problem was that there was not always a correlation—some of the longhaired students were honor students or star athletes—and even when a longhaired student was chronically absent or tardy or had poor grades, there was no guarantee that a haircut would resolve the issue. Arguments based on hygiene or safety were quickly knocked down, because girls also had long hair and were allowed to participate in labs and sports as long as they took sensible precautions. If girls could tie their hair back around Bunsen burners, so could boys.

By the early 1970s the outcome of any particular case depended on the language of the dress restrictions themselves and the testimony of witnesses, not on case law and precedent. Some of the dress codes were laughably vague; at a time when fashions were changing so rapidly, what exactly differentiated “extreme” from “conventional” hairstyles? When the offending haircut of a high school student was shorter than that worn by teachers from his own school, judges were quick to take note.21

The most common counterargument advanced by the schools was also the most difficult to support with actual evidence: that long hair was associated with delinquency or antisocial behavior. The testimony of dozens of administrators in these cases comprises a composite stereotype of “longhairs” that grew weaker as long hair became more common, less unkempt, and more acceptable to the wider public. The judge in Thomas Breen’s case expressed his skepticism of the claims of the principal regarding the meaning of long hair on boys:

In apparent seriousness he testifies: that “extreme hair styling” on boys especially “symbolizes something that I feel is not in the best interests of good citizenship”; that “whenever I see a longhaired youngster he is usually leading a riot, he has gotten through committing a crime, he is a dope addict or some such thing”; that “anyone who wears abnormally long hair, to the decent citizenry, immediately reflects a symbol that we feel is trying to disrupt everything we are trying to build up and by we I mean God-fearing Americans”; that the students at his high school share his opinion “that long hair symbolizes revolution, crime, and dope addiction”; that in his opinion “wearing long hair is un-American” in this day and age; and that its symbolism renders long hair a distraction.22

School superintendent Dr. Raymond O. Shelton of Hillsborough (Florida) County Schools testified that in his experience “there is a direct relationship between appearance, an extreme deviant appearance, and conduct, and behavior.” He also believed studies had shown that such persons tended to underachieve, although he was unable to cite any such studies.23 In the case of Howell v. Wolf, in Marietta, Georgia (1971), administrators reported a lengthy list of undesirable traits associated with long hair:

[Unkempt boys] generally contributed to disruptive activities in the school, were constantly tardy and had a greater percentage of absenteeism than other students. They were generally poorer students and were not well prepared for classroom work. They often combed and shook their hair in class and would play “peek-a-boo” through the long hair hanging over their face, all of which was disruptive to other students and teachers. They would gather as a group in one corner of the class, talk among themselves and often sleep. They had even eaten candy and popcorn and consumed soft drinks during class.24

In Lambert v. Marushi teacher Charles Cassell offered his opinion that long hair and unusual dress made students appear “arrogant and overbearing.” Like many others with similar opinions, he was unable to cite an instance where long hair had actually been a disruption, other than occasional clashes between students, which were usually initiated by shorthaired boys.25

U.S. District Court Judge James B. Parsons, in his opinion siding with David Miller in his refusal to conform to school hair rules, points out,

It must be made clear from the outset that this is not a case involving a revolutionary type young man, who by bizarre attire, filth of body and clothes, obscene language and subversive-like organizational activity, seeks to wage war against the established institutions of the community or nation. It is not a case involving youth commonly referred to as “beatniks” or “hippies” or “yippies.” It is simply a case of a seventeen year old boy wearing hair substantially longer than that permitted by the school’s regulations.26

While the first few media reports attempted to cast long hair cases in schools as light, trivial news stories, the number of cases and the rhetoric used on both sides reveals that serious ideological differences were involved. These differences only deepened as the controversy spread and escalated. For the longhaired boys and their allies, the right to have long hair was just one front on the struggle for individual expression. The issue wasn’t a trivial matter of hair and clothes, but the right to self-expression or to live one’s private life as one pleased. It was no small matter to take a school system to court, not to mention moving up the chain of the judicial system. The plaintiffs deeply believed that they were in the right, that their personal choice of grooming and dress were protected by the Constitution, and that the school administration thus had no authority to dictate their appearance or to discriminate against people whose appearance they did not like. The defendants in these cases were equally convinced that longhaired students presented a dangerous defiance, a threat of anarchy.

Just as school regulations initially made no reference to boys’ hair length, trousers had often been absent from lists of prohibitions for girls. Both trends caught the authorities unaware. In the case of girls’ clothing there had been rules about skirt length and dress styles, which were interpreted later to mean proscribing pants when girls began to demand to be allowed to wear them. By the late 1960s pants were added to the list of explicitly forbidden items in most school systems. The language in the dress code for the Laurel Highlands School District in western Pennsylvania was typical in its vagueness:

Neat and conventional skirts and sweaters, skirts and blouses, or school dresses are required. Hemlines should not be too short, nor clothing too tight. Slacks and shorts are not to be worn unless specifically permitted for special occasions. Attractive hair styles, appropriate makeup, and a minimum of jewelry are suggested.27

It is no coincidence that the earliest court cases related to female students’ wearing pants date to 1969, when miniskirts had reached their shortest length. Several of the dress codes specified skirt lengths that seem rather short if the objective was modesty: four inches above the knee (Miller v. Gillis, 1969), mid-thigh (Carter v. Hodges, 1970), and six inches above the knee (Wallace v. Ford, 1972). As was pointed out in every case, trousers could not possibly be considered more distracting or immodest than a miniskirt; in one instance the dress code had been modified just before the school year began because no skirts or dresses long enough to meet the requirement could be found in the local stores. Faced with a choice between immodesty and informality, informality won.

As the 1970s wore on, dress codes became more detailed and, not surprisingly, more difficult to enforce. Rather than simply allowing girls to wear pants and leaving the specific style up to them, some school systems found that if they allowed culottes (a divided skirt), a girl would show up in a jumpsuit with wide legs, arguing that it was no different from long culottes. The Perryville, Arkansas, school district agreed to permit jeans made for girls on the condition that if they had a front zipper it must be concealed by a tunic or square-tailed blouse. This particular school district admitted to having difficulty interpreting its own dress code, having sent girls home for wearing a midi-skirt (six inches below the knee), a knickers suit (a suit with knee-length gathered trousers), and a jumpsuit while admitting the outfits had caused no classroom disruption and were not immodest in any way.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was written to guarantee access to education, employment, and public accommodation and is associated in most Americans’ minds with the end of racial segregation and discrimination. So what does it have to do with white boys wearing long hair? At first not very much. But with the help of the ACLU, attorneys for the plaintiffs in long hair cases made the connection almost immediately, arguing that minors—a group not explicitly included in the law—had the same civil rights as adults. The basic question, appearing over and over in the case law, was whether schools have the authority to limit the rights of minor students (in the 1960s the age of majority was twenty-one, explaining why a few of these cases included college dress codes).

Which is more modest, dress or pants? (Circa 1970). Butterick B5817.

Image courtesy of the McCall Pattern Company, 2014.

The school systems first justified dress codes by simply asserting their authority to set institutional rules, and for a few years that argument was successful. But beginning in 1969 attorneys for the students began to cite Griswold v. Connecticut (the landmark Supreme Court case that established the “right to privacy”) to counter the schools’ “because I said so” argument. The first case to connect Griswold and appearance made its argument in this manner:

The right of privacy is a fundamental personal right, emanating from the totality of the constitutional scheme under which we live. The hairstyle of a person falls within the right of privacy which protects his beliefs, thoughts, emotions and sensations, and the board of education has no legal ground to proscribe the hairstyle of a pupil when the board interferes with his right to self-expression in the styling of his hair. His right to style his hair as he pleases falls within the penumbra of the constitution which protects his right of privacy and his right to be free from intrusion by the government.28

Judging from their dogged pursuit of the issue, the ACLU clearly also believed that dress codes violated the First Amendment by limiting a students’ freedom of expression. In several cases local ACLU attorneys contacted students who had been suspended from school for dress code violations, offering their support soon after the stories appeared in the papers. Within a year or two long hair had made the transition from a popular teen fad to an iconic emblem of rebellion, nonconformity, and protest. Journalist Daniel Zwerdling, then a sophomore at the University of Michigan, noted the shift in meaning in a very prescient editorial published in November 1968. Arguing that the attention to hair and appearance was diverting attention from more serious issues, he pointed out that most young men grow long hair and beards, “imagining what the pretty girl in class will say,” not as a political statement. The overreaction of authority figures only served to create the very defiance they imagined when they saw the long hair and beards. At a time when the United States was waging both a Cold War against the spread of communism and a real war purportedly to defend democracy in Southeast Asia, the establishment’s reaction also exposed the hypocrisy of “railing against totalitarianism and insisting on conformity.”29 From my vantage point in the early twenty-first century, 1968 seems to be an excellent candidate for the year that long hair went from minor irritant to “freak flag.” The evening news was scary; against the backdrop of an escalating Vietnam War and attempted revolution in Czechoslovakia against the Soviet Union, student protest culture had spread from Europe to major universities in the United States. The emerging Black Power movement, impatient with slow progress and obstructionism in resolving inequality, made whites uneasy and opened a generation gap in African American homes. When Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy were assassinated within months of each other, it seemed the year could not get worse, but it was only half over. The riots following the King assassination and the violent confrontations between police and demonstrators outside the Democratic National Convention in August helped “law and order” candidate Richard M. Nixon win the presidency. Small wonder that any tendency to nonconformity, including looking like a hippie or a Black Panther (even superficially), was perceived with alarm and greeted with hostility.

Workplace dress code cases were far less numerous than school cases and appeared later. Between 1971 and 1979 there were twenty-nine rulings on dress codes in the workplace, all but three concerning men’s hair or facial hair. Unlike the even split in the school-related decisions, the courts ruled in favor of the employer twice as often as the worker when it came to workplace decisions. One striking aspect of these conflicts is class: most of the employees were lower-level clerical, service, or blue-collar workers.

Many of the long hair cases in workplaces came directly from the passage of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which banned discrimination in employment. Section 703(a) of the act provides:

It shall be an unlawful employment practice for an employer—

(1) to fail or refuse to hire or to discharge any individual with respect to his compensation, terms, conditions, or privileges of employment because of an individual’s race, color, religion, sex, or national origin; or

(2) to limit, segregate, or classify his employees or applicants for employment in any way which would deprive or tend to deprive any individual of employment opportunities or otherwise adversely affect his status as an employee, because of such individual’s race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.30

The plaintiffs in these cases argued that restrictions on men’s hair length or women’s wearing slacks were a form of sex discrimination. This ended up being a surprisingly thorny issue, since employers had always seen the need to impose grooming standards either for safety or other reasons, but now found themselves having to reconsider those standards in a more inclusive workplace.

It is deliciously ironic that all of this fuss was created over sex discrimination as a result of Title VII. Sex as a prohibited criteria for employment practice was added by Southern Democrats as a “poison pill” designed to block the passage of the act—unsuccessfully, as it turned out. In many of the sex discrimination cases where it was alleged that a person’s appearance had led to not being hired, the court relied on the regulations developed by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) to help them navigate exceptions. The problem lay in the meaning of the words “bona fide occupational qualification,” or BFOQ, meaning skills or attributes that are not considered illegal hiring standards if they are a legitimate requirement of the job. (For example, the ability to lift fifty pounds is a BFOQ for a furniture mover but not for a bank teller.) The EEOC recommends that the BFOQ exception be applied narrowly and that it be used to specifically prohibit a refusal to hire based on stereotyped characterizations of the sexes, or because the preferences of co-workers, employers, clients, or customers favor one sex or another. Probably the most prominent case of this was in the 1972 Fifth Circuit Court decision on Diaz v. Pan American World Airways Inc. The airline had refused to hire male flight attendants, claiming their customers preferred females. The airline attempted to justify the restriction because the airplane cabin was a “unique environment in which the psychological needs of the passengers are better attended to by females.” Pan American lost.31

There’s an interesting relationship between business dress codes and the public. In Fagan v. National Cash Register (1973) the court noted that the company’s grooming policy had been initiated because of specific customer complaints about the personal appearance of employees. Just as employers could require that employees wear certain uniforms and had the right to package their products and services in the most attractive way possible, the court reasoned, they should also have the right to “package” their employees through the use of dress standards.32 So in Diaz v. Pan American, while the airline could not discriminate against male applicants for the job of flight attendant even if females might be more appealing to the traveling public, the court did not say that stewards and stewardesses would have to be “packaged” by dressing alike. Requiring all flight attendants to wear skirts and have shoulder-length hair would not meet the standards of a BFOQ.

As with the school cases, the plaintiffs in workplace dress code cases sincerely believed that barring men from wearing long hair and women from wearing slacks were forms of discrimination based on sex. Where the courts agreed, they relied on the EEOC guidelines and held the employers to a fairly strict standard in determining if the dress code distinctions reflected a “bona fide occupational qualification.” In Willingham v. Macon Telegraph Publishing Co. (1975), a male employee was fired for his failure to get a haircut. He was processing food, and workplace policy required male employees to wear hats and females to wear hairnets. When Willingham’s hair grew too long to be covered by the hat, he asked if he could wear a hairnet. His request was denied, and he was subsequently fired because he wasn’t abiding by the dress code. The court found that the regulation was not purely for sanitation purposes, since contamination could be prevented by having men’s hair contained within a hairnet, so the insistence that men wear hats instead of hairnets was based on grounds other than sanitation. Decision for the plaintiff.33

In the case of Donohue v. Shoe Corporation of America (1972), a shoe store salesman was held to have been discriminated against on the basis of sex because he was fired for having long hair when his employers did not have the same requirements for saleswomen. The court was fairly strong in condemning the discrimination based on hair length, arguing the following:

In our society we too often form opinions of people on the basis of skin color, religion, national origin, style of dress, hair length, and other superficial features. The tendency to stereotype people is at the root of some of the social ills that afflict the country and in adopting the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Congress intended to attack the stereotyped characterizations of the people would be judged by their intrinsic worth.34

In Aros v. McDonnell Douglas Corporation (1972), the court ruled similarly, saying, “The issue of long hair on men tends to arouse the passions of many in our society today. In that regard the issue is no different from the issues of race, color, religion, national origin, and equal employment rights for women.”35

Opposing arguments often engaged in thought experiments that revealed much about the attorneys’ attitudes. For example,

[If] an employer required all employees to wear their hair in ponytail style, or required all employees to wear dresses, it could not be said that different standards were being applied to men and women. It seems obvious, however, that such requirements would discriminate in operation against male applicants and so would be prohibited. This illustration emphasizes the fact that Title VII should not logically be viewed to require males and females to be governed by identical appearance codes.36

Other judges ruled that if the plaintiff says his way of dressing is “expressing himself” or “doing his own thing,” then style of dress and grooming is an extension of his personality, which they separated from gender identity. Put this way, the rule would have nothing to do with sexual bias, and “refusing to hire a longhaired male is merely avoiding a personality conflict between employer and applicant.”37 Employers were well within their rights, most of the courts agreed, in establishing dress codes to enforce a pleasing, uniform appearance as long as the rules did not prevent a class of people (men, women, African Americans) from being able to gain employment.

The evolution of the civil rights movement into the Black Power movement in the late 1960s further complicated questions of gender-appropriate grooming by intersecting them with expressions of racial identity. The popularity of the Afro hairstyle had little impact at the high school level, since the dress codes usually defined the proper hair length in terms of where it reached around the ears and collar. The Afro style made a much bigger stir in the military, though only very briefly. In 1969 airman August Doyle was court-martialed for disobeying an order to cut his Afro and was sentenced to three months of hard labor, fined sixty dollars a month during that time, and demoted. By the time he was released, however, the regulations had been relaxed.38 African American women opting for Afros also experienced criticism and discrimination, as in the case of stewardess Deborah Renwick, who thought her three-inch natural style conformed to the United Air Lines requirement for short hair. The airline grounded her, and she agreed to trim her hair to just two inches, but she was still dismissed. Eventually, like Airman Doyle, she won: outraged black leaders and professionals organized a boycott and she sued the airline for a million dollars. United Air Lines backed off, offered to rehire her with back pay and a cash settlement, and agreed to revise its grooming guidelines to be more inclusive.39

The cases involving African American plaintiffs offer particularly rich insights into interaction between gender and other factors as cultural constructions and social realities. Since the 1970s the case law involving dress codes has been disproportionately dominated by attempts by school or workplace authorities to control the appearance of people of color or members of minority religions. Few as they are, the very earliest cases reveal the constriction of available options for racial and other minorities and the increasing likelihood that their transgressions will be punished more severely.

The complete text of Title IX of the Education Amendments Act of 1972 reads,

No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.40

The passage of Title IX is largely remembered today for improving access to sports for girls and women. But Title IX was also used, along with the Fourteenth Amendment, to support boys’ claims that regulations on hair length discriminated against them by treating them differently from girls. Many of these cases were decided by the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) and later the Department of Education rather than through the courts. The first court case to be decided on this basis was Jacobs v. Benedict (1972) in the Ohio Appellate Court. The sex discrimination argument essentially eliminated the “safety” defense for banning long hair on male students. It is clear from some of the testimony that the authorities had initially thought that requiring boys to wear hairnets or to tie their hair in ponytails would shame them into getting haircuts, only to find, to their chagrin, the boys had no objection to those accommodations.41 But the Title IX argument was not always persuasive, especially in more conservative courts; in Trent v. Perritt the Fifth District Court reasoned that the law and the proposed HEW guidelines about gender discrimination that were being circulated did “not require that the recipient erase all differences” between boys and girls, and that requiring boys—but not girls—to have short hair was not discriminatory.42 In the long run the arguments against long hair were defeated indirectly; because Title IX opened home economics and shop classes to all students, the real requirements of safety and sanitation prevailed. In these settings all longhaired students regardless of sex needed to keep their hair under control by any means, including ponytails, hairnets, or bobby pins.

The military academies offered a different challenge under Title IX, because their dress codes—uniform clothing and grooming standards—were originally designed only for men. When the U.S. Military Academy at West Point admitted the first women in 1975, there was a flurry of attention in the press as to what they would wear and how their hair would be cut. The academy’s administration had worried publicly that women would not fit in, being unprepared for the discipline or the tough standards of West Point. But once the female students were accepted, the school held a fashion show to show how the classic uniform would be adapted. Their hair would be a short bob, not completely shorn, and women cadets would be issued purses. (This was necessary because the women’s uniform had six fewer pockets than the male version.) They would also wear bras, the school reported reassuringly. Instead of the tailcoat, the dress uniform jacket was modified to be straight in the back and worn with a knee-length skirt, not trousers.43

Title IX did have an impact on athletic clothing; predictably, it was quite different for boys and girls. For male student athletes it could be used to battle team dress codes requiring short hair and conservative dress. Uniformity and discipline were especially valued by athletic coaches, who were often the last holdouts, requiring athletes in football, tennis, and other sports to adhere to restrictive dress codes even when the rest of the students at the school were exempt. There was a rash of coach resignations in the early 1970s at both the high school and college level, with some coaches taking a dim view of the schools overriding their authority. The athletic director at a San Francisco–area high school predicted darkly, “This is the beginning of the end of all athletics.”44 Having so many professional and Olympic athletes dress contrary to school standards was also a blow to these restrictions. In every sport, students could point to examples of outstanding athletes with long hair, mustaches, and flashy personal wardrobes.

The situation for female athletes had been so appalling before Title IX that the immediate effects were not so much in terms of style as simple access. Even at wealthy schools, girls’ teams made do with old uniforms while the boys’ teams got new ones every year. Many girls’ sports did not have uniforms at all, much less warm-up suits and team footwear. Instead, they wore the same one-piece gym suits used for physical education. By requiring that teams have equal access to funding, Title IX ensured that girls’ and women’s teams were properly equipped for the first time. This had a ripple effect in the active sportswear market in the years and decades to come, as the number of women who had played sports in school jumped into the millions, many of them continuing to participate and complete long after graduation.

The legal battles prove two things: personal decisions about appearance are far from trivial matters, and the establishment dearly wanted to control the emerging culture. The role of gender norms in the long hair controversy was very different for men and women. The court decisions tended to skitter around the direct question of gender roles, preferring instead to emphasize the schools’ demand for order and discipline. Even this emphasis was gendered: the testimony of the authorities expressed a conviction that conformity and submission to rules is especially necessary for boys and young men. The dress codes themselves reinforced this distinction. Girls’ dress codes placed a premium on modesty; boys’ regulations were more likely to mention “conventional” standards. The Perryville, Arkansas, administrator in Wallace v. Ford testified that the objective of the codes was to prevent girls from wearing “revealing or seductive” clothing and boys from wearing “bizarre” clothing.45 West Point admissions officer Col. Manley Rogers was concerned that newly admitted female cadets were not ready for the rigors of the academy because, “You tell a 12-year-old boy about the need for discipline and tough training and he will understand; the girls have not been conditioned in that way.”46

For boys and men the dominant expectation was that males, especially those in subordinate positions, should respect and follow authority. Aspersions on their masculinity, such as the common suggestion that “you can’t tell boys from the girls,” were patently false but nevertheless used as a method of coercion and control, in an attempt to shame a shaggy-haired boy into compliance. My own reaction to hearing the phrase was amusement: it marked the commentator as an uncool, unhip square. My male peers were similarly unimpressed. When science teachers required them to wear hairnets in labs, the boys shrugged and donned the hairnets. At the restaurant where I worked after college, the male servers—all members of the same rock band—complied with regulations by wearing matching shorthair wigs and thought the whole fuss was pretty amusing.

There were clearly times when disapproval escalated to physical violence. Anti–long hair sentiment seems to have run especially high among football players, who appeared regularly as the antagonists in harassment and forced-haircut anecdotes. How much of this was the result of locker room and sideline rhetoric that accused boys of being “sissies” or “faggots” if they did not meet expectations? A North Shore Junior High School football coach, in an article in the Texas High School Coaches Association magazine, said that coaches should ban “individuals that look like females,” noting that long hair is “the sign of a sissy.”47 It took high-profile examples to counter these stereotypes; Olympic swimmer Mark Spitz is credited with breaking the long hair barrier for many athletes, probably in part because of the popularity of his door-size poster among young women. While the shorthair establishment tried to frame the issue as masculinity versus effeminacy, young men reframed it as “new man versus old man.”

Olympic swimmer Mark Spitz, 1972.

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution/Art Resource, New York.

Girls who violated dress codes were usually just sent home to change or actually given a change of clothes to wear, but they seldom faced suspension or expulsion, even for repeated violations. Boys were threatened with more serious consequences. It could be argued that clothes were easier to change than hair, but the disparity in the number of legal cases and the severity of the punishments suggest that the real underlying issue was resistance to authority. One measure of the importance of conformity and submission to authority in postwar masculinity is the narrow range of styles available to men and boys. The institutional reaction to nonconformity, as seen in the dozens of hair cases, is even more powerful evidence.

Besides concerns about female modesty and male compliance, the main objection to both male and female fashions of the late 1960s was that they were too casual. That was clearly the problem with girls wearing pants to school or women wearing them in the workplace. It was also the objection raised to jeans in general. The same rising tide that eliminated hats and white gloves had also swept away the barriers between clothing for work and leisure. The sense that the social fabric was loosening elicited different reactions from different people. Some found the new standards not just more comfortable but a sign of greater individual freedom of expression and thought. To others it marked the decline of civility and social standards that had provided a different kind of “comfort”—the assurance that stems from a society regulated by clear rules and standards.

Note that I resisted the temptation to associate these perspectives with particular age groups. If this had been a truly generational battle, there would be no culture wars today. The baby boomers would have won simply by outliving the opposition. But the many examples of conflict, even violent confrontation, between shorthaired and longhaired students suggest otherwise. Adults who defended men’s right to wear long hair found themselves characterized as either heroes or traitors. Consider the case of new headmaster Robert Thomason at Horace Mann, an all-male private school in New York, who announced the suspension of the dress code to a standing ovation from the 545 students at a school assembly, but then faced opposition from parents and alumni.48

In the end all of the Sturm und Drang over appearance ended in a stalemate, on the national level. The U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear dress code challenges again and again, in 1968 (Ferrell v. Dallas), 1969 (Breen v. Kahl), 1970 (Jackson v. Dorrier), 1971 (Swanquist v. Livingston, King v. Saddleback), 1972 (Olff v. East, Freeman v. Flake), and 1973 (Lansdale v. Tyler, Karr v. Schmidt, New Rider v. Board).49 The most eloquent defender of the civil libertarian side came from Justice William O. Douglas, who dissented from the denial of certiorari in nearly every case and thought the court should have heard the cases. Writing in his 1968 Ferrell v. Dallas opinion that a nation founded on the Declaration of Independence should allow “idiosyncrasies to flourish, especially when they concern the image of one’s personality and his philosophy toward government and his fellow man,” Douglas added,

Municipalities furnish many services to their inhabitants, and I have supposed that it would be an invidious discrimination to withhold fire protection, police protection, garbage collection, health protection and the like merely because a person was an offbeat, nonconformist when it came to hairdo and dress as well as to diet, race, religion, or his views on Vietnam.50

In his 1971 Freeman v. Flake dissent, Justice Douglas noted, “Eight circuits have passed on the question. On widely disparate rationales, four have upheld school hair regulations . . . and four have struck them down,” which he believed to be a compelling reason why the Supreme Court should take up the case.51 Instead, the highest court let the widely divergent case law in each circuit set the precedent for their respective regions. Across the nation people on both sides believed they had won when in fact the basic conflict between personal expression and community standards has never been resolved.