C Experiment on: Preference for Material or Treatment of Two Popular Songs among Twelve Subjects*

Material vs. Treatment

Introduction

In a market situation where the names of bands and band-leaders seem to count for more than whatever they play, and where they are trademarked according to the so-called style (»King of Swing«), this style of presentation of whatever it may be appears to play a greater role than ever before. It is not too difficult to see how the development of light popular music leads to this particular concept of style. The stock arrangements of the hundreds of mass-produced and standardized hit tunes which flooded the market then as now tended to cause all dance bands to sound alike. And so the dance men started using special arrangements, identifying their individuality and the individuality of their orchestra with the characteristics of the arrangements played. The increase of the importance of arrangements in recent years expressed the growing need for a belated individualization of the material which otherwise would be indistinguishable. The actual songs which are clothed in this style seem to play a less important part. This study is based upon the idea that people today are more concerned with the perfection of the machinery and the way something is transmitted than with the music itself. (This tendency is not confined to light popular music. It can be found in serious music listening as well. This is indicated by the usual stress laid upon names of soloists, conductors and orchestras in serious concerts instead of emphasizing the programs.) In swing, however, there is in a sense more justification for this behavior. Here the material is rather inconsequential and not very characteristic. Frequently, as in the »St. Louis Blues« and the »Tiger Rag«, the melodic material is thoroughly inconsequential and this very characteristic allows a variety of treatments. Now, this very prevalence of style over material in »swing« is the effect of standardization. In every dance type not only is the basic rhythm rigidly defined, but also the meter, number of bars, and even the harmonic proportions. Moreover, a number of these dance types imitate one given pattern of one particular successful hit. Furthermore, in view of the mass sales of sheet music and records, it is necessary that the basic material of a hit – that is, the melody and corner harmonics – must be extremely simple, and this again limits any sort of invention. This leads to complete triviality; but that would endanger the chances of success for a piece of music because it can be kept in mind only if it is distinctive in some way. Paradoxically, the consideration of popularity means a threat to that very popularity. So, since these fundamentals of the material cannot be altered, the only possible escape is to make this material more distinctive by the manner of its presentation, by embellishing and ornamenting it without touching its fundamental simplicity which remains preserved in the music the listener receives when he buys the sheet music. Therefore, any spontaneity of musical invention to be found in light popular music lies in the treatment and not in the material. It is not accidental that real musical experts in light popular music are to be found not among the so-called composers but among arrangers and sometimes band-leaders and bands soloists.

In addition to this tendency to emphasize the treatment of light popular tunes, there is a second tendency. One of the essential functions of modern light popular music seems to be that of upholding the impression of immediacy – of fostering the illusion that the music is improvised, spontaneous, constantly changing and entirely free of the bonds of standardization. This illusion cannot be produced by the material but only by the treatment. For obviously if the material itself were handled in this manner, it would lose the very standardized character which is the presupposition for its success. (Still, the success of song-hits cannot be understood only in terms of standardization or non-standardization. These terms must be properly related before we can arrive at a complete understanding. It may be defined preliminarily as music which is fundamentally standardized, but apparently non-standardized.) Then, too, since the material is fixed and not spontaneous, it is impossible to make it sound spontaneous and improvised, so this must be done by its presentation. The absorption of older feudal or negro tendencies in modern light popular music serves really to create this illusion.

We must add, however, that the freedom of improvisation, variation and the like in swing varies greatly. Although we admit that a certain amount of real improvisatory jamming still exists, it still seems fairly certain that they are much more frequently fixed and pre-determined than the listener is made to believe, if they are not in fact actually written down. Furthermore, the freedom of improvisation is greatly limited by the standardized framework of the music. One of the results of the rigid definitions of the harmonic cornerstones of a melody and its rhythmical length has been the working out of new standards among the anti-standard improvisations, and the constant recurrence of certain formulae for improvisations. The advocate of the spontaneity of light popular music will probably call these recurring formulae the »swing style«. Since, however, they are bound to the limitations of the standardized pattern, and not to the spontaneity of the improvisation itself, we refrain from calling them the »style«, and prefer instead the term, »treatment«,a since we consider the former term entirely unsuitable for swing.

Since a preponderance of treatment over material can be found in the music, it should accordingly be expected that people will therefore respond more strongly to the treatment than to the material. The issue, however, is much more involved than it appears on the surface. Only a pure empirical investigation can settle it because there are strong counter-tendencies to those which we have outlined here, which grow out of those tendencies that we have just mentioned. We become able to cope with them by a closer analysis of the implications of the increase in the importance of treatment over material. From the start the difference between material and treatment must not be handled as if it were clear-cut, and the weight of the treatment must not be over-rated.

On the surface, the treatment may appear comparable to the variation technique in serious music. But this is not so, even of the jammed swing treatment. Here the material is not actually »developed«; it is merely disguised. The arranger does not aim at drawing consequences from the given material as much as he hides it and plays the game of asking the listener, »Where is it now?« It is a sort of musical hide-and-seek. The fundamental proportions are not changed and the jammed choruses are mere circumscriptions of the basic material which remains the same and which remains obvious. Apparently the Goodman record of »Avalon« (used in our experiment) is exempt from this rule, especially in the piano chorus where the basic harmonies are maintained. But this exemption is deceptive. The freedom of the harmonic treatment in the Goodman version does not mean that the harmonic scheme of the music is developed, that it becomes broader, more dynamic or more differentiated. It is much more similar to an aberration. One of his jobs is suspending the musical scheme for a few bars, leaving the listener helpless: but then he very soon returns to it. The aberrations of the Goodman version are concerned with the arbitrary playing of false notes and similar devices so prevalent in swing more than with an attempt fundamentally to develop the basic material by variations. He is just pulling his listener’s leg.

This has certain consequences for the whole question of treatment vs. material. Strictly speaking, we cannot speak of treatment, but only about »make-up« in the same sense that a woman’s face remains fundamentally the same in spite of the rouge on her cheeks and lips and the mascara on her eyelashes. Now, if the treatment is only »make-up« the importance of the underlying material is probably greater than we might expect. It would be wrong to say that a man prefers the makeup on the face to the face itself. It would be equally wrong to say that listeners prefer treatment to material. Correctly phrased, the question would ask, »Do they prefer made-up material to non-made-up material?« The question of treatment vs. material, then, holds good only within these limitations which adequately consider the importance of the invariants of swing practice – that is, the triviality of the basis of the entire treatment.

It seems more reasonable to consider the question of »makeup« vs. »non-make-up« because at first sight it seems that the higher musical tide chooses treatment automatically – that is, swing – whereas the lower, more primitive type chooses material – that is, sweet.1 Now, the range of musical understanding of our subjects does not follow this assumption (as we shall show later). One of the possible explanations of this inconsistency is the question of caliber. That is, even more sophisticated and pro-swing listeners prefer a sweet number which is well done to a swing number which is only average. But there may be a different, and perhaps a more deep-reaching explanation. If the treatment is really a mere disguise of something fundamentally unaltered, then just the more advanced musicians or musical experts who react to our question may sometimes be ready to prefer the »thing itself«, no matter how primitive, to a version which makes it appear more than it really is without changing it. If we assume that the progressive attitude in modern architecture is that attitude which is critical of ornamentation, we may assume that, paradoxical as it sounds, the »sweet« people are more modern than the »swing«, in this sense, or at any rate could be more modern because they are more hostile to a false veneer and prefer a musical product adequate to the musical content. This could explain the fact that musical experts do not necessarily show a positive response to swing even though it seems to display a higher degree of musical expertness.

There is a last possibility which, although it does not come out as a result of this experiment, may be shown by a more refined experimental set-up. This possibility is clearly connected with the problem of the rubato. A generally accepted sign of higher musical taste is the absence of any rubato, that is, any modification of the musical ground beat. Part of the contempt of swing fans for old-fashioned adherence to sweet is based upon the fact that »sweet« people are considered to be too fond of rubato. Jitterbugs call it »schmalz«. (This is particularly evident in the Guy Lombardo-style.) But the question of the rubato is not quite so simple. Certainly the criticism of rubato is justified to a great extent. The people who approve of it display a lack of musical discipline and a preference for their private emotions (which in most cases are simply residues of past conventions, long since disappeared). Nevertheless, this type – primitive, undisciplined and musically inadequate as it may be – still displays in his rebellion against the iron ground beats which are the sacred rule of the swing fan, a spontaneity and immediacy which has disappeared from the field of swing, remaining only in the pseudo-form of improvisations which must fit the rhythmical schedule at the beginning and at the end. Possibly some part of certain person’s reactions against swing (the reactions of completely naive people as well as musicians who can no longer stand the swing machine) is based upon this very rebellion and grows out of their spontaneity. It may be that they hate the mutilation of freedom in swing, no matter how doubtful their own concepts of freedom may be. In this respect the so-called sentimental light popular music may preserve trends which could be considered, from a sociological viewpoint, more progressive than the general trends of swing. It is significant that practically all established norms of our music life today agree in their contempt for the rubato and the bad taste of sweet. Our theory, a priori strongly in favor of the underdog, is very much inclined to defend the lowest type of light popular music, namely sentimental music. Still, oppositional motives of this sort may be found wherever the sweet type prevails, and the interpretation of the conflict between material and style certainly should not overlook these tendencies.

There is an additional factor, though, which comes into play. The question of material vs. treatment is not simply a question of the tune and its simple harmonization on the one hand, and its embellishment or jammed version on the other. In this sense, it is a question of two »styles«. Light popular music today does not consist only in the different types of swing and syncopated music. There is another type of treatment which fundamentally renounces the idea of presenting material in a more interesting fashion by altering it; instead, it sticks as closely as possible to the material and attempts to make it attractive merely by the quality of sensual sound colors. Although it borrows the sound colors partly from swing, it is on the whole the heir of older types of salon music from which it has borrowed that essentially sentimental character which we have already mentioned in the discussion of the rubato question. This type of music shows its connection with that other, more decisive trend of modern light popular music by a certain colorfulness and richness at which it constantly aims. We are speaking of the type of sweet music expounded today mainly by Guy Lombardo and André Kostelanetz. The music in principle sticks to the material which it presents with the sound colors but never with the rhythm of swing.

Insofar as this »treatment« is characterized principally by the emphasis laid upon the material, the question of material vs. treatment coincides to a certain extent with the question of sweet vs. swing. Our experiment has tried to combine both viewpoints.b

Some finer reservations ought to be made without which the experiment, isolated as itis, couldlead to premature inferences. First of all, the styles of different bands are much more similar than they are advertised to be or than they and the swing fan wants himself and others to believe. The importance of varying tastes and selecting between the styles, too, is probably less than most people would guess. The listener regulating his radio-dial is led to believe that in the last analysis it depends upon his whim which band or which style he listens to. As a matter of fact, however, the whole mechanism of plugging, the similarity between the music offered to him and all the ways of establishing current values which are at the disposal of the large organizations, determine him much more than he is aware. Even the very belief in the »difference« is a means of advertising a standardized product.c Today there is some doubt if musical instrumentalists who deliver mass products to the man in his home really care much about his taste as they make him believe in order to make him swallow their products more readily.

The problem of this experiment, then, was: What is the comparative importance of material and style of treatment and preferences for certain popular tunes?

The material used consisted of two popular songs which have lasted well, but which are not at present being featured. We chose »Avalon« and »The Russian Lullaby«. Each of these tunes has been recorded in swing style and sweet style. Thus four records were used: (for further information about them, cf. the feature analyses given in the interpretation of Experiment II, The Tape Study).

»Avalon« – sweet style – Lombardo

»Avalon« – swing style – Goodman

»Russian Lullaby« – sweet style – Garber

»Russian Lullaby« – swing style – Berigan

Twelve subjects were used. They were all from metropolitan areas, six males and six females, all between the ages of twenty and twenty-eight. Five of the twelve were of Jewish extraction, four were of German extraction and three were English. All had had highschool education, and some had had some college training. One subject, referred to in Table I as number ___,2 is a young public school music teacher. One subject, referred to in Table I as no. 12, may be considered a »swing fan«.

The procedure: The paired comparison technique was used in rating preferences for the four records. The records were presented in pairs. After each pair of records the subject indicated which of the two he liked best. The records were presented in the following order:

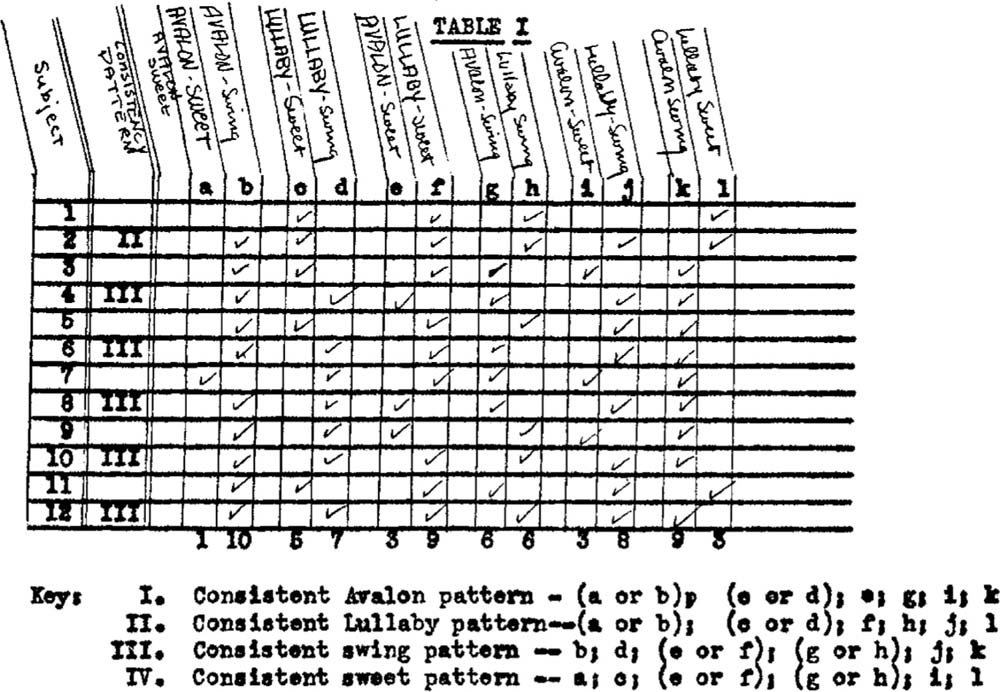

The results and interpretation: Table I shows the choices made by each of the twelve subjects after each of the six combinations of records.

The table is read as follows: Subject no. 2 shows consistency pattern no. II. According to the »Key«, given below the table, consistency pattern no. II shows a consistent preference for »Lullaby«. We may now check to see if subject no. 2 actually did show this pattern of preference. In the first group of two records, he may check either the first or the second record because neither is »Lullaby«. In the second group, he may choose either because both are »Lullaby«. In the third group, he must check the second record. In the fourth group he must check the second. In the fifth group he must check the second. In the sixth group he must check the second. Since subject no. 2 has checked in this fashion, he is said to have expressed a consistent preference for »Lullaby«.

Preferences for Swing and Sweet

By totaling checkmarks, we find that the sweet records were checked in 24 cases, and the swing records were checked in 46 cases. However, in column 3, both records are sweet, and in column four both are swing, so to get a total on preferences we must subtract 12 from each of these totals. Thus the sweet records were preferred in twelve cases (26%) and the swing records were preferred in 34 cases (74%). This result fits the main result of the study, that is, the prevalence of treatment over material. By its very nature swing demands a greater role from treatment, and sweet demands a greater role from material. However, we must make specific reservations at just this point. As we have pointed out, our subjects were all young people; the antagonism between swing and sweet takes the form of an antagonism between generations. The younger generation is usually inclined to prefer swing. They associate sweet with sentimentality, old-fashioned prejudices and even hypocrisy; while swing appeals to them for its »freedom«, a certain excessiveness, and even sex on the one hand, and on the other for its more sportive requirements – keeping the time while improvising, the tendency of the music to »test« the listener, which particularly impresses young people in this country. If we assume that this is a general trend among younger people, the result of this experiment as far as sweet and swing are concerned must be considered somewhat tautological. It only shows that young people react according to the reaction to be expected from young people. To make the experiment more valid in this respect it must be enlarged to include people of different ages. Another factor which might be reflected in this result is that our subjects were chosen from the metropolitan area. People growing up in rural conditions, who are more restricted, are likely to react more favorably to sweet.

(It will be noted that subject no. 1 failed to mark two of the pairs. This accounts for the total of 70 checks instead of 72.)

Preferences for »Avalon« and »Lullaby«

Now, by totaling in terms of tunes instead of sweet or swing, we find that »Avalon« was preferred in 21 cases (46%) and »Lullaby« was preferred in 26 cases (54%). For these figures columns 1 and 2 were, of course, omitted since no preference for tune was expressed here. This difference (8%) is very small, and considering the small number of subjects in our sample, almost negligible. Therefore we refrain from any definite interpretation here. From a purely musical viewpoint this difference is hard to understand, and since it is so small, we consider its validity highly doubtful. As a melodic curve »Avalon« is certainly more elaborate, richer and more distinctive than the »Lullaby«. Musically the latter is pretty poor and the only thing in its favor is its sentimental appeal. The experiment, however, has refuted the strength of this appeal since the majority of our subjects prefer anti-sentimental to sweet in general. The most plausible explanation here is that in our group, at least, the recognition value of the »Lullaby« was greater than of »Avalon«. Of course this cannot be viewed as a result of experiment, but only as a hint in the direction of future experiments on the problem of recognition value which we shall have to carry through later.

Consistency

Probably the most significant way of ascertaining which is dominant and which is recessive, in considering material and style, is to see which factor seems to dictate patterns of preference.

In order to do this, we must set up for key patterns. If the subject shows »Avalon« consistently, he would check either a or b, either c or d, and e, g, i, f, and k (see Table I). This pattern might be set up in more concrete form as follows:

»Avalon« – (a or b); (c or d); e; g; i; k.

The other three keys are set up in similar fashion:

»Lullaby« – (a or b); (c or d); f; h; j; l.

Swing – b; d; (e or f); (g or h); j; k.

Sweet – a; c; (e or f); (g or h); i; l.

Now, by studying the table in terms of these keys, we find that the »Avalon« pattern does not appear at any time. The »Lullaby« pattern appears once – subject no. 2. The swing pattern appears five times – subjects 4, 6, 8, 10 and 12. The sweet pattern does not appear.

Thus far, patterns of consistency have appeared in six out of the twelve cases.

In the case of subject no. 1, who did not indicate a preference in two cases, there appears to be a tendency toward the »Lullaby« pattern. Subject no. 1 had marked j as her preference in the fifth group but then erased the mark. If this may be counted as indicating a slight preference for j over i, we would have a »Lullaby« pattern in this case, since either a or b fit that pattern.

A coincidence is worthy of note. On the basis of very short acquaintance with the subjects, the experimenter assigned numbers to their test forms, giving the highest number to the subject who seemed to know the most about jazz music, and the lowest number to the one who seemed to know the least. The others, being ranged between. It would seem that when the papers were stacked in this way, evidence of consistency and taste would cluster around the high numbers.

Instead there appears a perfect distribution of consistency patterns throughout the sample. Subjects 1, 3, 5, 7, 9 and 11 do not show consistent patterns, and subjects 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 12 do show consistent patterns.

Limitations

Certain limitations of this study should be pointed out:

1.) As indicated under The Subjects, our sample was neither representative nor large enough to allow unreserved generalizations.

2.) The phonograph on which the records were played was not of excellent caliber. The faulty quality of the reproduction might have something to do with the preference for swing over sweet, since poor quality probably detracts more from sweet music than from swing, for a very simple reason. One of the major features of swing treatment is the rhythmical element, the interrelation between ground beats and cross rhythms. Now, the rhythmical element is not affected by the quality of the phonograph. In sweet, however, where no rhythmical issues exist, the actual stimuli – apart from the melody itself – consist almost entirely of the sound. The sound element is not isolated, either, but to a certain extent it also affects the harmonies upon which the swing versions are based. Now it is this very sound quality which is certainly distorted by poor phonographs. Thus the experiment has not been quite fair to sweet, and any repetition of the experiment will have to take the quality of the phonograph into consideration.

3.) At the beginning of the experiment, the complete record was played each time. However, it soon became evident that this process would be long and boring to the subjects. Consequently, two choruses from each record were played instead of the whole record. Two choruses seem to be the minimum, especially for a swing record, because one chorus is necessary to set the theme, and of course one jammed chorus is necessary to indicate the style of the soloist.

At this point we must be very critical of our own experiment. It is clear that the cutting down of the selections interferes with the experiment to a great extent, seriously endangering its validity. Some of the reasons may be stated. First of all, precise reactions take place only within the whole. To put it more cautiously, if they do not take place within the whole, we must start with the whole anyhow before being able to say anything about the role of the whole or the parts in determining the listener’s reactions. For example, we can correctly judge how an individual is impressed by the straight chorus and the jammed chorus only if we consider them as they are really related. It is possible that the listener to only the jammed chorus may dislike it because he lacks the melodic treatment. When he hears the straight chorus, however, and remembers the melody, he may enjoy the way it is modified, embellished, and even concealed. On the other hand, taken in itself, a tune may be meaningless, but may turn out to be quite pleasant for the listener when he sees the different purpose it can serve (for instance, in the »Tiger Rag« which we used in some other experiments). Thus the experiment would be much more valid if it were carried through with whole records instead of isolated parts. This tendency is reinforced secondly by the fact that the listener is more intent and listens with more concentration in the beginning than he does later on. (This experiment took almost two hours – a long time, particularly when we consider the limitations of the basic material consisting, as it did, of very simple and trite tunes.) This lowering of concentration is now furthered by the selection of parts. The reduction to parts, however, was necessitated because no subject would have listened to the complete recording again. But in listening only to parts, the listener does not take it as seriously as when listening to the whole. It is more like a rehearsal than a performance, and it was obvious that at the very moment we played only parts of the record, a relaxation took place among our sample. People started to talk, laugh, and the concentration which they showed at first dwindled. We had to choose between boredom (which would probably have created an aggressive mood among the subjects) and remaining patient, although on a lower level of concentration. We chose the second possibility but we must point out that as far as the objective results, and not just the subjective comfort of the subjects concerned, it was probably as disastrous as the first possibility would have been.

Now it is much easier to offer this criticism than to suggest any real improvement. For the value of the experiment consists mainly in the thoroughness of combinations helping us to check any possible reaction of the listener. If we consider it our task to keep the whole experiment on the same level, as long as it may take, then we must necessarily renounce the idea of playing the whole selection all the way through. As a substitute, we tentatively suggest that when the experiment is repeated, both tunes should be played in the simple sheet version on the piano. This would be sufficient to give the audience a rough orientation to the whole piece. But on the other hand, the difference between the piano and the record sound, and the difference between the treatment on the records and on the simple sheet version, would exclude any possibility of confusing the whole, heard in a piano version, with the record version. It is most unlikely that they will prefer what they hear on the piano to the stuff they get in the actual experiment. It is more difficult to select the parts from the records. It certainly would be no good to offer them continually the beginning and the first jammed chorus which would tire them very soon; and it would also be bad to continually select the beginning and the end of each record where the disproportion between the thematic material and the treatment would be too obvious. We must consider here the fact that the repetition as a whole works against the material and in favor of the treatment. That is, people become bored much sooner with the melody that can very easily be recognized when it is played in its simplest sooner than when they are presented with jammed choruses which sometimes (as in the case of the Goodman »Avalon«) present them with rhythmical difficulties which take longer to overcome even for trained musicians. Thus, the mere fact of repetition acts in favor of treatment which, as far as the experiment goes, is very hard to overcome. The best procedure seems to be this: the material should be played to the subjects on the piano, and after they are familiar enough with it, a chorus should be selected. This chorus should maintain the material clearly enough, but not in too primitive a form; yet, on the other hand, some of the more extreme jammed choruses should not be used.

One thing, however, could be said in favor of such a procedure. The advantage of swing over sweet, which is shown by the tendency of the material to become more characteristic than the treatment, is not specific to this experiment but works the same in practice. It would not be astonishing to find that the real reason for the preference for swing over sweet is this very same element which is so hard to exclude from our experiment. If this is true, if the material itself necessarily proved boring and the treatment itself necessarily proved interesting, then it could not, and should not be excluded from the experiment. The only thing is to handle the question fairly and give sweet, especially the material, the best chance possible. This is the reason for choosing a modified jammed version of the experimental selection.

4.) The difference between the range of styles is much greater, probably, than the difference between the caliber of the two tunes. Thus the dominance of style shown in the results might be attributed to the nature of the experimental data. However, the experimenters feel that, taken in general, the range of styles in jazz is comparatively large, and the range of difference between tunes is comparatively small. Therefore, the materials used are considered by the experimenters to be fairly representative of the field of jazz music.

Conclusions

After all the reservations stipulated in our discussion, the result of the experiment itself may be stated as follows:

1.) Style is more important than material in determining preference.

2.) Five subjects out of twelve showed perfect consistency in choice of favorites in terms of style.

3.) One subject out of twelve showed perfect consistency in choice of favorites in terms of tune.

4.) Swing was chosen over sweet in 74% of the cases.

5.) Consistency in taste does not appear to have any correlation with ranking of subjects in terms of »expertness in listening« (ranking according to subjective criteria of experimenters).