The Eastern Question

The complexities of the Eastern Question, which so troubled the chancelleries of Europe, were greatly exacerbated by the insurrections that rocked the Ottoman Empire from 1875. All the Great Powers had kept a watchful eye on events within the Empire, and none more so than Russia. In St Petersburg, as in other capitals, the possibility of the final disintegration of the Ottoman Empire was kept under constant review. For Gorchakov, and for Tsar Alexander II, there was a particular concern, and that was the destruction of the Black Sea Clauses of the settlement of 1856. Russian diplomacy had always had this as one of its objectives, and the Franco Prussian War of 1870 provided a golden opportunity.

Accordingly, on October 31 1870 the Russian government formally denounced the neutralisation of the Black Sea. It was not so much a decision born of a perception of military need; it was more a step taken to remove the humiliation of the Treaty of Paris. It found the signatories to that treaty in too weak a position to do anything about it. France could in any case do nothing. Bismarck, of course, with a war to win and always concerned to maintain Russia’s friendship, had no problem at all with the Russian objective, although he could have wished that the declaration had come later. His concern was that it might lead to a conflict between Russia and Britain, and it was for this reason that he proposed a conference. For Britain, the issue was the sanctity of treaties; Bismarck’s concern was sharpened by a threat from Lord Odo Russell that Britain would go to war to uphold a treaty with or without allies.1 Bismarck saw this as mere bravado, but it was an uncomfortable situation. On the other hand, an international conference, provided that it was excluded from consideration of the Franco Prussian war or its outcome, would defuse the situation. So it proved; with the tacit understanding that the Russian demand would be met if the declaration was withdrawn and the proposal put forward at a conference, the Great Powers agreed to meet in London. If this merely rubberstamped the inevitable outcome of the issue, it did nonetheless have the important consequence that the parties accepted the principle that the terms of an international treaty could not be arbitrarily changed by unilateral action.2

If the revision of the Black Sea clauses effectively reopened the Eastern Question, it was the events of 1875-6 in the Balkans which made it a question that must be answered. The problems facing the Christian Slavs of Bosnia and Herzegovina led to a tour in May 1875 by Franz Joseph of Dalmatia; it was, as was intended, seen as a gesture of support to the discontented Slavs within the Ottoman Empire. Meanwhile the Pan-Slavist party in Russia, with whose aims Ignatiev, the Russian ambassador in Constantinople, was certainly in sympathy, stepped up their support for the Slav populations of the Balkans. Throughout the Russian Empire charities were founded to provide funds for the relief of the mounting number of refugees that crossed Turkish borders into Austria-Hungary, Serbia and Montenegro.3

Misha Glenny has pointed out that the rise of Pan-Slavism, which united many strands of Russian society, had by the end of the 1860s become synonymous with the Orthodox Church. This, in turn, created dilemmas for the movement, not least when a dispute between the Greek and Bulgarian churches broke out. Ignatiev was the most prominent and most assertive of the Pan-Slavists; he was also the most ambitious, seeking for Russia the command of Constantinople and the Straits, and the unquestioned leadership of the Slavs. It was for Russia, not for the Slavs, that he wanted to see sweeping political change, as he explained:

Sooner or later… Russia must fight Austria-Hungary for the first place in the Balkans and for the leadership of Slavdom: only for the attainment of this task should Russia make sacrifices for the Slavs under Austrian and Turkish rule and be solicitous for their freedom and growth in strength. To aim merely at emancipating the Slavs, to be satisfied with merely humanitarian success, would be foolish and reprehensible.4

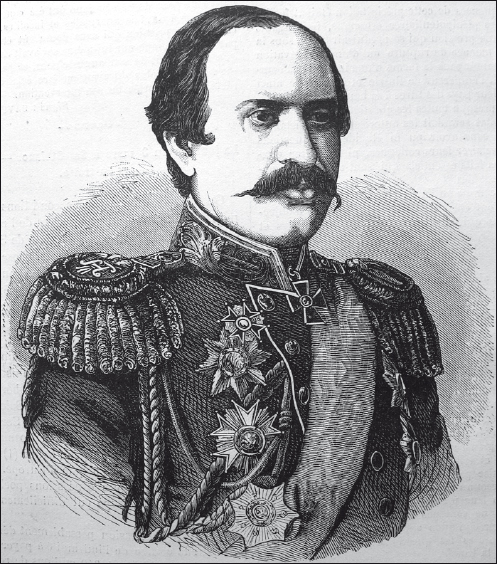

Ignatiev did not himself make Russian policy, although he influenced it substantially at times; there were others who took a much more conservative view, including his opposite number in London, Count Peter Shuvalov. Gorchakov’s position was somewhat between the two, and his direction of Russian policy was wholly pragmatic. Pragmatism also dictated the policy of Count Julius Andrassy, the onetime Hungarian rebel who became minister of foreign affairs in Vienna in 1871. The military leaders of the Dual Monarchy, whose influence over the Emperor was considerable, were unequivocal in their attitude to Bosnia and Herzegovina; for them, to annex the provinces was essential, for the protection of Dalmatia and to enable the constant unrest in the provinces on Austria-Hungary’s borders to be brought under control. Andrassy, whose first concern was to see the Ottoman Empire kept in existence as long as possible, did not want an increase of the Slav population of the Dual Monarchy, telling Gorchakov that annexations ‘would lead to the ruin of the empire and would therefore amount to suicide.’5 He could see all too clearly that the absorption of these provinces would be a meal that would prove completely indigestible. Only if the Ottoman Empire completely disintegrated would it be necessary for Austria-Hungary, as a defensive measure, to annex Bosnia and Herzegovina in order to deny them to Serbia.

Count Shuvalov, Russian Ambassador to Britain. (Russes et Turcs)

In Serbia, Prince Milan Obrenovic was of a much more conservative disposition than his predecessor Prince Michael; but although official Serbian policy was no longer irredentist, popular feeling certainly was, and by the time of the revolt in Herzegovina the national mood was militant in the extreme. As tension rose in the Balkans, therefore, Serbia could no longer be counted on not to intervene.

For Germany the Eastern Question had only a downside. Bismarck, who famously observed in December 1876 that there was nothing in the Balkans worth the healthy bones of a single Pomeranian musketeer, was concerned only to ensure that a balance was kept between Russian and Austria-Hungary, and was ready to agree to anything with which they both agreed. Britain, on the other hand, had a greater concern; in her case it was to preserve the existence of the Ottoman Empire, so that here at least there was a common interest with Austria-Hungary. From the British point of view it would be the tidiest solution for the Turks to suppress the insurrections on their own without involving the international community. Finally France, for her part, had no particular interest.

Andrassy, effectively taking the lead among the Great Powers, put forward a proposal on the part of the Three Emperors’ League that they should send their consuls into the affected provinces to endeavour to mediate. France, which objected to being ignored, was on August 14 invited to join the mission, as was Italy; and, albeit reluctantly, the British consul also took part. His view was that the trouble had been caused by Serbian agitation. The consuls heard much of the local grievances; but the rebel leaders wanted autonomy under a Christian prince or occupation by a foreign power until the grievances were resolved. This was unacceptable to Andrassy; and the Sublime Porte was not under any circumstances prepared to agree to this. Instead, a decree was published which promised alleviation of taxation, religious freedom and equality before the law, all of which had been promised before and never honoured.6

Next, Andrassy contemplated the imposition of a reform programme on the Ottoman government. Becoming aware of this, Abdul Aziz was determined to beat him to it by issuing his own programme for reform on December 12; he told Ignatiev that to allow foreign interference would be like committing suicide. However, this reform programme was merely a rehash of the former programmes, and Andrassy continued to work on his own plan, which he embodied in a note to the Great Powers on December 30. They all accepted it (although in Britain’s case only because the Turks asked them to) and it was formally presented to the Porte on January 31 1876. However, although the Turks found it broadly acceptable, the insurgents did not, regarding the reforms as inadequate and worthless without international guarantees. It was an outcome which came as no surprise to Bismarck, for one, and he had already begun to consider alternative ways in which the increasingly pressing issues might be resolved.

His first approaches, to Britain and to Russia at the beginning of January 1876, fell upon stony ground. Although Russell thought Bismarck’s desire for some understanding with Britain was sincere, he did not think that there was need for an immediate response; and Lord Derby, the Foreign Secretary, was content to let the matter rest. Gorchakov was also suspicious of Bismarck’s motive in offering to mediate as well as his suggestion that Bosnia go to Austria and Bessarabia to Russia; he preferred to deal directly with Andrassy. A further approach in February through Lord Odo Russell was met with still greater suspicion by Lord Derby. It was still widely believed that Bismarck was a wolf in sheep’s clothing, and that at this time dealing with him was extremely risky.7 On this occasion at any rate Bismarck was being misjudged; he sincerely wanted to see a settlement of the Eastern Question since above all he wanted to avoid conflict between Russia and Austria; if the reform plans were not going to succeed, his suggestion of some limited territorial rearrangement might achieve his object.

On May 11 1876 Bismarck met with Andrassy and Gorchakov in Berlin to make another attempt to produce a generally acceptable solution. Bismarck had had a premeeting with Andrassy, and had tried and failed to convert him to the notion of some partition arrangements; when Gorchakov joined them he had brought with him the hope of creating autonomous states. Andrassy would not wear that either; and in the end the Berlin Memorandum that emerged was effectively a restatement of the original Andrassy Note. It called for the Ottoman government to provide means for the resettlement of refugees, for these means to be distributed by a mixed commission, for Turkish troops to be concentrated in a few specified locations, for Christians to be allowed to retain their arms for the time being and for the consuls to monitor the reforms.

As before, France and Italy agreed; but this time Britain did not. Affecting to be offended by the manner in which the Memorandum was communicated – Disraeli complained that ‘England has been treated as though we were Montenegro or Bosnia’ – the British government feared that the proposals were designed for the ‘disintegration of Turkey.’8 Disraeli was pleased with himself, believing that in his rejection of the Memorandum he had driven a wedge between Austria and Russia.

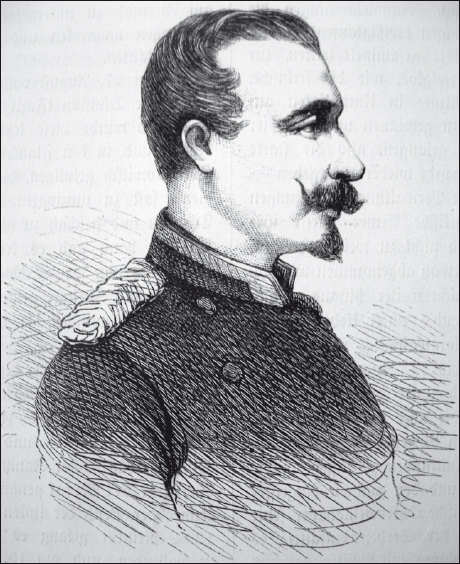

Lord Derby, Britain’s Foreign Secretary. (Fauré)

While all this was going on the situation within the Ottoman Empire was steadily deteriorating. On May 29 Abdul Aziz had been deposed, while in April the revolt had spread to Bulgaria. Then, at the end of June 1876 Serbia and Montenegro declared war on Turkey.

Serbia took this step in the teeth of the official advice from the Russian government. Immediately before the declaration of war the Tsar sent a message to Prince Milan urging him to preserve peace at any price, and warning that he would be left to his fate if he did not do so. But Serbia’s leaders were more impressed with the urging of Ignatiev that now was the time to take action.9

Command of the army was entrusted to the Russian General Mikhail Cherniaev, previously successful in Russian operations in Turkestan. Known as the ‘Lion of Tashkent,’ Cherniaev was an unfortunate choice. Although his capture of Tashkent in 1865 with less than two thousand men ensured that he was the hero of Russian imperialists, he was not a sound military commander. It was because of his championship of the Slav cause that he was selected, and his personality was unsuited to the demands which leadership of the Serbian army would make of him. One commentator observed:

Cherniaev was not a practical person – he lived in his imagination. He was always surrounded by a multitude of people who said yes to his fantasies and secured his trust. Like Don Quixote Cherniaev never recognised obstacles, he fought all his life against evil genii and giants … As a commander his qualities of will unquestionably predominated over his critical faculties, his heart over his reason.10

Emperor William I of Germany. (Illustrirte Geschichte des Orientalischen Krieges)

Cherniaev had arrived in Belgrade in May, and was followed by some 700 Russian officers as volunteers. In all it was estimated that some 4,000 Russian volunteers ultimately went to Serbia to take part in the war. As well as the provision of human resources in this way, the Russian organisations collecting funds in the Pan-Slavist interest were said to have transferred the equivalent of twenty million francs to Serbia. All this meant that the Russian government must prepare itself for the possibility of a great Slav victory, with all the uncertainties that this would create. Accordingly Gorchakov readily accepted the suggestion made by the Emperor William I that he should consult with Andrassy on a one to one basis to hammer out a joint programme of action in relation to the Serbo-Turkish conflict and its possible outcome.

Their meeting, at which they were accompanied by Tsar Alexander and the Emperor Franz Joseph, took place at Reichstadt on July 8. Their agreement was not reduced to writing, but essentially it amounted to an acceptance of the principle of non-intervention. If Turkey won, the status quo would be restored. Bosnia and Herzegovina were to be dealt with in accordance with the Andrassy Note and the Berlin Memorandum. If, on the other hand, Turkey was beaten, Serbia and Montenegro would gain some territory in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the rest of which would be annexed by Austria. Russia would recover Bessarabia and some territory in Armenia. If the Ottoman Empire collapsed altogether, Bulgaria and Rumelia would become autonomous, and also Albania (although this did not appear in the Russian note of the understanding). Greece would be allowed to make territorial gains. The deal pleased both sides; but it did not provide for direct Russian action in the Balkans, and this was in due course to appear a grave defect.

Serbian leaders hoped by their action in declaring war to promote a general insurrection across the Balkans; but neither Roumania or Greece responded, believing that it could not succeed without the active support of at least one of the Great Powers. This was not forthcoming, despite the conviction of Jovan Ristic, the Serbian Foreign Minister, that Russia could not remain passive. In this view he was sustained by a belief that the Pan-Slavs would define Russian policy.

Bulgarian refugees. (Ollier)

The original intention was that the Serbian army, some 130,000 strong, should concentrate for an advance on Nish, where the principal Turkish forces were located. The plan was revised because of the risk of Turkish attacks upon both eastern and western flanks of the advance, and the Serbian army was organised in four corps with a view to advancing on all fronts. This was a dangerous dispersal of force; there was a frontier line of over 120 miles. The Serbian high command had, it has been pointed out, totally failed to pay attention to recent military history, which had conclusively shown that the power of modern infantry weapons enabled good defensive positions to withstand heavy assaults, and that only well trained, highly disciplined and well equipped troops could succeed in the assault.11 The shrewd old Turkish leader Omar Pasha, who had watched Serbian manoeuvres for many years, thought that the peasant mass that constituted the army ‘would take to its heels after the first bullet had been fired.’

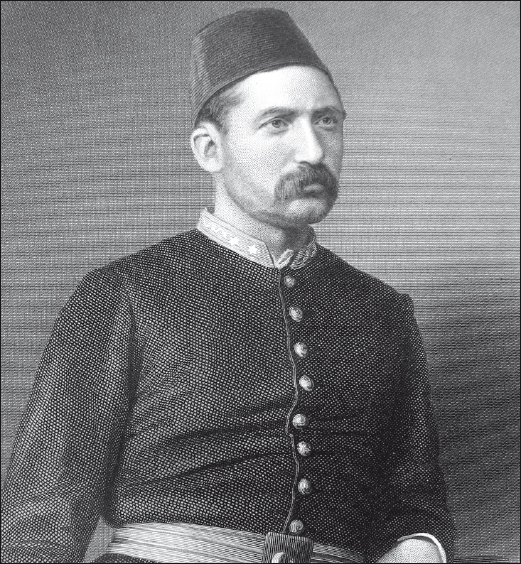

At first all seemed to be going well. The Serbs crossed the frontier and made ground at all points. By the end of July, however, the Turks, commanded by Suleiman Pasha, were in a position to counter-attack. Suleiman Pasha, aged only thirty-eight, had acquired a high reputation. He had fought in Montenegro, Crete and the Yemen, and had risen to be Director of the Military Academy at Constantinople. There, he was very much at the centre of power, and he had taken an active part in the deposition of Abdul Aziz. Now, with a large army of well-equipped and well-trained troops he drove back the Serbs at the end of July, capturing Knjazevac and Zajecar.

Suleiman Pasha. (Hozier)

Prince Milan lost his nerve completely, but was prevented by the government from seeking an armistice. Instead it was resolved to return to the original plan take to up a position in front of Nish, from where the Turks threatened Belgrade. For another month the Serbs, much better in defence than attack, held their positions. On September 1 however, at Alexinatz on the Morava river some seventeen miles north north-west of Nish, Cherniaev’s army was decisively defeated, and the road to Belgrade lay open. Even the most fervent nationalists now lost heart, and a ten day ceasefire was negotiated upon stiff terms insisted on by the Turks.

While this was being negotiated, the situation in Serbia began to change. The increasing flow of Russian volunteers, and the upsurge in pro-Slav activity in Russia, brought above a complete change in the public mood, both there and in Serbia. It was not something that the Russian government could ignore, and the Tsar made a speech after the Russian army manoeuvres that autumn in which he said he had tried to preserve peace, but that if the country’s honour was attacked he would know how to vindicate it.

All this immensely strengthened Cherniaev’s position, and at his urging the armistice, which had been briefly renewed, was allowed to lapse on September 28. The resumption of hostilities, however, ultimately brought the Serbs no better fortune. Fierce fighting on the River Morava culminated in the Battle of Djunis on October 29, when a Turkish offensive smashed the Serbian army and advanced towards Belgrade. Cherniaev, enraged by his defeat, cried out to every Serbian officer he could find: ‘Your Serbs all fled, and my Russians all perished!’12 Confronted with the obvious and total defeat of the Serbs, Russia intervened to demand another armistice, to which the Turks at once agreed. The Great Powers now proposed a conference in Constantinople to settle the terms of peace, which must necessarily include Montenegro, whose forces had succeeded in overrunning most of Herzegovina.

Bulgarians destroying a Turkish mosque. (Illustrirte Geschichte des Orientalischen Krieges von 1876-1878)

The war had been disastrous for Serbia. It is estimated that one sixth of her total population had been mobilised and that 10% of the male population was killed or wounded. The country’s economy completely collapsed. These sacrifices on the part of Serbia had not only failed to achieve their object; they never could have done so:

She was too weak and too unprepared to conduct the war with Turkey with any prospect of success. Even if she had overcome Turkey she could not have obtained Bosnia and Herzegovina, since they had already been allotted to Austria. But the significance of her entry into war lay not in its immediate result, but in the moral influence it had on the South Slavs, and in the further events it conditioned.13

In the immediate future, however, it was events that had already occurred in Bulgaria that were ultimately to determine the course of Balkan history.