the legal price in £ of an ounce of gold in coin in London, and

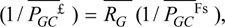

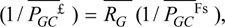

the legal price in £ of an ounce of gold in coin in London, and  the legal price in Fs. of an ounce of gold in coin in Hamburg, the par of exchange

the legal price in Fs. of an ounce of gold in coin in Hamburg, the par of exchange  computed on gold was given by

computed on gold was given by  hence:

hence:It is also forgotten, that from 1797 to 1819 we had no standard whatever, by which to regulate the quantity or value of our money. […] Accordingly, we find that the currency varied in value considerably during the period of 22 years, when there was no other rule for regulating its quantity and value but the will of the Bank.

(On Protection to Agriculture; IV: 222‒3)

When Ricardo made his first appearance in print in August 1809, England had been for twelve years in a monetary situation unprecedented in history. The bank note issued by the pivotal institution in the banking system – the Bank of England1 – was no longer convertible into coin since 1797, and in the second half of the first decade of the century the gold and silver coins had progressively been melted and exported. Apart from small copper coinage, the circulating medium was thus composed almost exclusively of inconvertible paper-money, including newly issued low-denomination Bank of England notes (£5 and under). This situation changed dramatically the English monetary system inherited from the eighteenth century (Section 1.1), while the international monetary relations with Continental Europe were disturbed by the Napoleonic wars (Section 1.2). As may be expected, this unprecedented situation that was marked by a fall in the internal and external value of the pound sterling gave rise to intense debates known in the literature as the “Bullionist Controversy” (Section 1.3). Three successive rounds may be distinguished in this controversy, the first one (1797‒1803) being without Ricardo (Section 1.4).2

1.1 The English monetary system at the time of Ricardo

The recoinage of silver coins in 1695‒1699 and the monetary reform of 1717, inspired by Isaac Newton then Master of the Mint, had firmly established the English monetary system on a bimetallic foundation: the monetary unit (the pound sterling, divided in 20 shillings of 12 pence each) was defined on the basis of an ounce of silver 222/240 (that is, 0.925) fine valued 62 pence and coined in “crowns”, while an ounce of gold 22/24 (that is, 0.91667) fine valued £3. 17 shillings 10½ pence was coined in “guineas” (of 21 shillings each). However, the monetary ratio resulting from this legal valuation – that is, the relative price of gold to silver in coin – equal to 15.21, was higher than on the Continent where it was at or below 15 (for details, see Shaw 1895). The consequence was that, in spite of the prohibition of exporting and melting the coin, the comparatively undervalued metal (silver) was exported and the comparatively overvalued one (gold) was imported. In the middle of the eighteenth century, silver was less and less brought to the Mint to be coined and England shifted progressively to a de facto gold standard.

The state of the gold coinage – the fact that guineas were worn or clipped – was all the more scrutinised since some authors (such as James Steuart) had shown that the “debasement” of the coin (their actual weight in gold being lower than their legal one) was responsible for the market price of an ounce of gold bullion being higher than the legal price of an ounce of gold in coin, so that the current value of the currency in terms of gold was below its official one. This situation became particularly acute in the 1770s when the alteration of the gold coinage was added to the already deteriorated state of the silver one. Inspired by Lord Liverpool, an Act of 1774 ordered the recoinage of the golden guineas. As for the silver coins, they were not recoined but became legal tender up to £25 only; above this sum, they were to be taken by weight and not by tale. Both measures reinforced the de facto gold standard.3 As we will see below, however, the question of whether the standard of money in England was actually silver or gold was still hotly debated in 1810 when the causes of the depreciation of the pound were discussed. The drying-up of the circulation of guineas and of silver coins in England – most of them having been fraudulently exported – raised in 1810 the question of the consequences of a circulating medium that was composed almost exclusively of Bank of England notes made inconvertible since 1797 and extended to low-denomination ones. This was the start of the Bullion Controversy (see below).

After the end of the Napoleonic wars in 1815, the stabilisation of the currency was looked for in the reform of 1816 that established the gold standard de jure, making silver coinage a token currency: the mint was closed for silver to the public and the Bank of England, only the government having access to it; silver coins became legal tender up to £2 only; and their current legal value (66 pence per standard ounce) was made higher than their mint price (62 pence) by a 6.45 per cent seignorage. Ricardo entirely approved this currency reform, as he declared in a speech before the House of Commons on 24 May 1819:

He thought it right here to pay the tribute of his approbation to the late excellent regulations of the mint. He entirely approved of making gold the standard, and of keeping silver as a token currency. It appeared to him to be a solid improvement in the system of our coinage.

(V: 16)

A new gold coin, the “sovereign” of £1, was issued on the basis of the legal price of £3. 17s. 10½d. per ounce standard, the “mint price” that was unchanged since 1717. As before it was coined without seignorage, but the mint continued keeping the metal during two months before delivering the coins, and this amounted practically to a coining charge of a little less than 1 per cent at the ruling interest rate.

In 1694 the Bank of England had been created as a device to salvage public finance: being a joint-stock company, it allowed raising funds to be lent to the Crown, which was no longer able to do so. The first role of the Bank was thus to manage the public debt, and it derived large profits from this activity – a question that would become controversial in the 1810s. Its secondary role was to become important: for the first time in the history of banking, it could issue bank notes not only against bullion (as the Bank of Amsterdam already did; see Gillard 2004) but also by discounting commercial bills; these notes were convertible into full-bodied (that is, undebased) coins. This innovation, coupled with the monopoly of note issue in a 60-mile radius around the City of London and the prohibition of any other joint-stock banking in England, made the Bank of England acquire a prominent position in the English monetary system in the second half of the eighteenth century (see Clapham 1944).

The banking system was three-tiered. Country banks issued notes outside the London area, by receiving gold or discounting bills. To guarantee the convertibility of their notes, they kept gold reserves deposited (at interest) in London banks or in the Bank of England vaults; they also kept a reserve of Bank of England notes, since their only legal obligation was to give Bank of England notes for their own notes on demand. According to Ricardo, the quantity of country-bank notes was consequently regulated by the quantity of Bank of England notes:

As the country banks are obliged to give Bank of England notes for their own when demanded […] the Bank of England is the great regulator of the country paper. When they increase or decrease the amount of their notes, the country banks do the same; and in no case can country banks add to the general circulation, unless the Bank of England shall have previously increased the amount of their notes.

(High Price; III: 87‒8)

In 1797, the suspension of the convertibility of notes into coin only applied to the Bank of England but the effect was the same for country-bank notes, since they remained convertible in Bank of England notes that were no longer convertible into coin.

The second tier of the banking system was composed of London banks, whose business was to receive deposits, operate transfers, and discount bills for coins or Bank of England notes – but not for notes of their own, because of the monopoly of the Bank of England on note-issuing in the London area. Like the Bank of England and the country banks, the lending activity of the London banks was subject to a maximum rate of interest of 5 per cent, a limitation imposed by the Usury Laws; in practice, however, this limitation was easily evaded, as testified by Ricardo when he was examined by the Select Committee on the Usury Laws on 30 April 1818:

It appears to me, from the experience which I have had on the Stock Exchange, that, upon almost all occasions they [the Usury Laws] are evaded, and that they are disadvantageous to those only who conscientiously adhere to them. […]

Question: In what manner evaded?

In the particular market with which I am acquainted, namely, the Stock Market, they are evaded by means of the difference between the money price and the time price of stock, which enables a person to borrow at a higher rate of interest than 5 per cent, if possessed of stock, or to lend at a higher rate, if the difference between the money price and the time price, affords a higher rate.

Question: Has that been acted upon extensively?

Very extensively; it is the usual and constant practice.

(V: 337‒8)

The gold reserves required by the activity of the London banks were kept at the Bank of England, which was the third tier of the system. Two consequences resulted from this institutional network. First, since London was the centre for foreign payments, any demand for bullion generated by them (in case of a negative foreign balance) was translated into an “external drain” of Bank of England metallic reserves, when it became more beneficial to obtain gold from the Bank of England through conversion of its notes than in the bullion market. Only “sworn-off gold” could be legally exported, that is, gold declared as previously imported. In fact, the prohibition of melting and exporting the coin was easily evaded, and it was not therefore an obstacle to an external drain. Second, any demand for gold coins originating at any level of the domestic monetary system ended up in an “internal drain” of Bank of England metallic reserves, because the vaults at Threadneedle Street were de facto the central safe of the system. Not only was the Bank of England supposed to provide on demand the metallic currency for which its notes were considered as substitutes (they were not legal tender until 1833): in times of emergency, it was also supposed to provide, thanks to an enlarged note-issuing, the liquidity that was urgently needed. The Bank of England had become the dernier resort (lender of last resort), as Sir Francis Baring would call it in 1797, when this need became crucial.

The problem was that this increasingly pivotal role of the Bank of England was not accompanied by a corresponding consciousness of that role by its governors and directors, who were more interested in the security of their own establishment than in the needs of the monetary and financial system as a whole, and consequently reacted to a gold drain and/or a financial panic by contracting instead of enlarging their issues. This counterproductive behaviour was observed during the crisis of 1793, when, although the exchanges were favourable – preventing any “external drain” – the outbreak of the war with France led to a financial panic which degenerated into a high demand of guineas and Bank of England notes. Forced by the legal convertibility of its notes to cash them, the Bank of England reacted by refusing to discount even good paper further, intensifying the panic that was only overcome by the Government announcing a massive issuing of Exchequer bills to relieve the liquidity pressure.

A new alarm occurred in 1795, when, after two war years, an explosive cocktail of financial transfers to the Continent, bad harvests in England, and expanded Government borrowing from the Bank of England led again to a drain of the latter’s metallic reserves. This combination of external circumstances and of domestic expansion of credit would pave the way for the later controversy between those who would explain the monetary crisis by external factors and those who would blame an overissue of notes. The Bank of England responded again to the pressure on its reserves by a proportional rationing of its discounts, and again this behaviour started a wave of bank and commercial failures over the country. In February 1797, rumours of a French invasion provoked a panic which led to a run on some country banks. Because of the structure of the banking system outlined above, the Bank of England experienced a heavy drain of its reserves, which was felt as threatening the existence of that central institution. On 26 February, a Council convened by Prime Minister William Pitt ordered the Bank of England to suspend cash payments of its notes until Parliament had deliberated on the subject; this order was confirmed by the “Bank Restriction Act” passed on 3 May and was to remain in force till 24 June. Extended by further Acts of Parliament, this unprecedented inconvertibility situation would in fact last until 1819 (and 1821 for the return to the pre-war parity of the Bank of England note and the coin), that is, way after the troubled times – the Revolutionary and later Napoleonic wars with France – which were directly or indirectly held responsible for it.

1.2 International monetary relations in Europe: London, Paris, Hamburg

As early as the sixteenth century there existed a monetary integration of Western Europe, thanks to the organisation by Italian merchant-bankers of a network of fairs on which foreign bills of exchange were actively traded (see Boyer-Xambeu, Deleplace and Gillard 1986, 1994a). This network evolved in the seventeenth and eighteenth century through the shift of power among bankers’ communities and financial centres (see Braudel 1981‒1984; McCusker 1978; Boyer-Xambeu, Deleplace and Gillard 1995). At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Europe provided the only example of an international system composed of three interconnected monetary zones, with two standards operating side by side in the system, and one superior bank4 in each zone: the Bank of England in a gold-standard zone (restricted to England), the Bank of France in a double-standard one (extending to southern Europe), and the Bank of Hamburg in a silver-standard one (extending to northern and eastern Europe).

Apart from special circumstances, international arbitrage on gold and silver did not operate through the barter of one metal for the other; bullion traders usually considered arbitrage between the market of one metal and the foreign exchange market. For example, the export of gold from London to Paris was financed by the sale of a bill in francs in London or followed by the remittance of a bill in pounds purchased in Paris. Thus, the working of the international monetary system under two standards depended on the relationship between the exchange rate for each pair of currencies and the corresponding commercial par of exchange for each metal (that is, the ratio of the market prices of that metal in the two countries). Although the working of this international bimetallism was jeopardized by the suspension of the convertibility of the Bank of England note and by the Napoleonic wars, it was never interrupted. It may thus be useful to give some indications about the foreign exchange and bullion trades between London, Paris, and Hamburg, since their characteristics appear in Ricardo, who was particularly aware of them (see Appendix 1).

In London, the operating mode of the bullion market and of the foreign exchange market had not changed much since the eighteenth century. The price of standard gold (916.66/1000 fine) and standard silver (925/1000 fine) bars was quoted and published on the metal markets every Tuesday and Friday. The course of the exchange was quoted the same days, for short and two-month bills with Paris and only two-month bills with Hamburg. By “short” exchange one meant the equivalent of today’s spot exchange, with a delivery in a few days. By “long” exchange (two or three months), one did not mean today’s forward exchange but the immediate payment of the bill purchased in one currency for the future delivery of the other currency. Such “long” foreign bill could be either kept in portfolio as any commercial paper or discounted in the foreign discount market when cash was needed there. In spite of the war, the exchange with Paris and Hamburg was quoted without interruption, but the range of variation of the exchange rate, constrained by the cost of sending gold or silver rather than a bill of exchange, was abnormally high during the war, because of the cost of smuggling the metal in breach of the blockade decreed by Napoleon (see Appendix 1). On the metal markets, silver was always quoted but the official quotation of gold was irregular until 1810.

The French monetary system was on a double standard and the franc was since 1803 defined on the basis of 3444.44 F per kilogram of pure gold and 222.22 F per kilogram of pure silver, giving the well-known monetary ratio of 15.50 (see Thuillier 1983). The alloy used to mint the actual coins being 900/1000 fine, they were legal tender for respectively 3100 F per kilogram of gold 900/1000 fine and 200 F per kilogram of silver 900/1000 fine. The public paid the cost of minting coins (a seignorage of 0.29 per cent on gold and 1.50 per cent on silver), so that the legal price of coined metal was higher than the legal price of bullion purchased by the mint (respectively 3434.44 F for pure gold and 218.89 F for pure silver). After the experiments of the Caisse d’Escompte (1776‒1791) and of the assignats during the Revolutionary period, the Banque de France was founded in 1800 and granted the monopoly of note-issuing in Paris in 1803 (see Plessis 1982‒1985; Leclercq 2010). It issued notes by discounting commercial paper already countersigned by other bankers. The discount rate was constrained by the legal maximum of 6 per cent, but the Bank of France invariably applied a uniform rate of 4 per cent. Its notes were convertible at par on demand into gold or silver coins, at its choice; it could also agree to cash its notes with a premium in coins of the metal chosen by the holder. In the Paris metal markets, the relative deviation (prime) was quoted and published daily per kilogram 1000/1000 fine of gold and silver by reference to a given rate (tarif du commerce) equal to the legal price of bullion purchased by the mint. The course of the exchange with London and Hamburg was quoted daily for one-month and three-month bills. The exchange with London was interrupted between 1806 and 1814 (but bills on Paris were quoted in London) and the exchange with Hamburg was always quoted. In the metal markets the regular quotation of gold and silver suffered only a few exceptions.

Unlike London and Paris, Hamburg was not the monetary and financial capital of an integrated State. Its importance in these two domains was due to the fact that it was a relay centre for payments between Western Europe and the partitioned Germanic territories, as well as Northern and Eastern Europe, especially Sweden and Russia (see Achterberg and Lanz 1957‒1958). The creation of Die Hamburger Bank in 1619, seventy-five years before the Bank of England, was an early manifestation of this relay role. Modelled after the Bank of Amsterdam, the Bank of Hamburg was a municipal deposit and transfer bank, which in addition had a monopoly on all foreign exchange transactions. All the drafts drawn and remittances made in Hamburg had to be accompanied with a book entry in the Bank of Hamburg. This institution did not practice discounting, nor did it issue bank notes and deal with public finance. Its operations were written in a special unit of account, the Mark banco, divided into 16 Schillinge containing 12 Pfennige each. This Mark banco was different from the current Mark, which had no role in the domestic or international wholesale trade: all the quotations at the Hamburg Exchange were made in Mark banco, except those for cereals and alcohol. Beginning in 1725, there was an official par value of 123⅓ current Mark for 100 Mark banco, but the premium between these two types of Mark was quoted daily for each of the principal coins (local or foreign) circulating in Hamburg. The existence of the Bank of Hamburg thus introduced a separation between silver by weight (whose accounting representation, the Mark banco, was used by big business through book transfers) and silver in coin (used in retail domestic transactions).

The Mark banco was defined as a silver weight. Starting in 1770, the Cologne marco of pure silver (233.855 grams today) was quoted at 27 Mark 10 Schillinge banco. The Bank of Hamburg received silver bullion at this price, and it gave back this metal at 27 Mark 12 Schillinge banco, thus making a profit of 0.45 per cent. Gold was quoted every Tuesday and Friday for a limited number of coins. The silver market reflected the rules applied by the Bank of Hamburg: bars of different degrees of fineness were quoted every Tuesday and Friday, with the differences in the quotations corresponding exactly to variations in fineness. Thus, there was a single market price for pure silver bullion, equal to 27 Mark 10 Schillinge banco (the price at which the Bank of Hamburg received deposits in bullion). Short and two-and-a-half month bills on London and two-month bills on Paris were quoted daily.

1.3 From Hume to the Bullionist Controversy

What monetary theory were observers equipped with when convertibility of the Bank of England note into coin was suspended in 1797? Breaking with the mercantilist tradition, it was mainly inherited from David Hume’s vision of an automatic adjustment mechanism of the aggregate quantity of money, which ensured the stability of its value. The following excerpt from Hume’s essay Of the Balance of Trade (1752) sums up the adjustment mechanism which ensures internal and external monetary stability:

Suppose four-fifths of all the money in Great Britain to be annihilated in one night, and the nation reduced to the same condition, with regard to specie, as in the reigns of the Harrys and Edwards, what would be the consequence? Must not the price of all labour and commodities sink in proportion, and every thing be sold as cheap as they were in those ages? What nation could then dispute with us in any foreign market, or pretend to navigate or to sell manufactures at the same price, which to us would afford sufficient profit? In how little time, therefore, must this bring back the money which we had lost, and raise us to the level of all the neighbouring nations? Where, after we have arrived, we immediately lose the advantage of the cheapness of labour and commodities; and the farther flowing in of money is stopped by our fulness and repletion. […] Now, it is evident, that the same causes, which would correct these exorbitant inequalities, were they to happen miraculously, must prevent their happening in the common course of nature, and must for ever, in all neighbouring nations, preserve money nearly proportionable to the art and industry of each nation. All water, wherever it communicates, remains always at a level.

(Hume 1752: 311‒2)

Applied to the symmetrical case of an increase in the quantity of money – the case that would be discussed during the Bullionist Controversy – this so-called price-specie flow mechanism worked for a pure metallic monetary system in the following way. Suppose that for any reason the quantity of money increases in a greater proportion than output. The Quantity Theory of Money predicts that the value of money will fall, and this will be reflected in increased money prices of all commodities produced nationally. At the ruling exchange rate, these commodities will become dearer than foreign ones, and the balance of trade will sooner or later become negative, depressing the exchange rate until it reaches the bullion export point. Then gold and silver coins will be exported or melted into bullion for export, and this will decrease the domestic quantity of money, reversing the movements of prices and consequently the balance of trade, until the initial situation is restored: “All water, wherever it communicates, remains always at a level.” This hydraulic conception introduced interdependence between the domestic value of money (inversely related to its quantity) and its external one (determined by the balance of trade). Because of this interdependence, the same stabilising mechanism, which relied on a quantity adjustment of domestic monetary circulation and a price adjustment of exports and imports, operated in any circumstance, whether exorbitant or common, and for whatever cause of disequilibrium, domestic (for example, an abnormal increase or decline in the quantity of money) or external (for example, a sudden negative or positive foreign balance).

This was not the opinion of James Steuart in An Inquiry into the Principles of Political Economy, published in 1767. Against Hume who praised the metallic basis of money because international flows of metal automatically eliminated any positive or negative foreign balance, Steuart explained the absence of self-adjustment by the inconveniences attached to metallic money. International transfers of precious metals, supposed to adjust the balance of trade, depended on the market prices of bullion in the various trading nations, which were affected by monetary factors such as the debasement of the coins by wear and tear and the existence of a seignorage on coining. A country could thus experience an outflow of bullion while the quantity of money was not in excess and the balance of trade not against her. Even worse, such outflow had a negative impact on the domestic market for credit: in a country like England where gold to be exported was obtained at the Bank of England against convertible notes, the fall in its metallic reserve led the Bank to reduce its discounts, and this resulted in a shrinkage of overall credit that hurt the economy. Rather than relying on a self-adjusting mechanism that was in fact prevented from operating by these malfunctions of metallic money, it was the task of the State to intervene actively so as to prevent outflows of bullion, by adapting the domestic monetary system (recoinage, imposition of a seignorage when there existed one in the other trading nations) and by paying the interest on the money to be borrowed by the Bank of England in Amsterdam in case of a temporary adverse shock on the foreign balance (for more details, see Deleplace 2015d):

If this be a fair state of the case, I think we may determine that such balances ought to be paid by the assistance and intervention of a statesman’s administration.

The object is not so great as at first sight it may appear. We do not propose that the value of this balance should be advanced by the state: by no means. They who owe the balance must, as at present, find a value for the bills they demand. Neither would I propose such a plan for any nation who had, upon the average of their trade, a balance against them; but if, on the whole, the balance be favourable, I would not, for the sake of saving a little trouble and expence, suffer the alternate vibrations of exchange to disturb the uniformity of profits, which uniformity tends so much to encourage every branch of commerce.

We have abundantly explained the fatal effects of a wrong balance to banks which circulate paper; and we have shewn how necessary it is that they should perform what we here recommend. There is therefore nothing new in this proposal: it is merely carrying the consequences of the same principle one step farther, by pointing out as a branch of policy, how government should be assisting to trade in the payment of balances, where credit abroad is required; and this assistance should be given out of the public money.

(Steuart 1767, II: 346; III: 370‒1)5

Steuart’s anti-Humean approach6 contrasted with that of Adam Smith in An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, published in 1776. The question is debated in the literature about whether Smith actually used Hume’s price-specie flow mechanism. It is, however, easy to see that Steuart’s emphasis on the fact that gold to be exported was obtained at the Bank of England could be introduced in the analysis of a mixed monetary system (of metallic specie and convertible bank notes) so as to preserve Hume’s conclusions. An abnormally great quantity of money could result from banks issuing an excess quantity of notes (overissue), but, if the notes were convertible, bullion exports would again correct the excess; these exports would now be fuelled by converting notes at the banks of issue rather than by gathering coins in domestic circulation. If the banks were sound – that is, if they kept enough metallic reserves – the adjustment mechanism operated as in Hume, the only change being that the aggregate quantity of money was reduced in its note component.

The 1797 crisis showed that, even if the banks of issue were sound, the adjustment mechanism could be at fault and require a radical and undesired change in the monetary system: the suspension of convertibility, which degenerated into an enduring fall in the value of the currency. This was a denial of the Humean approach and pressed for new debates.

The name “Bullionist Controversy” was coined (at an unspecified date) after the Bullion Report issued in 1810 by the House of Commons’ Select Committee “appointed to enquire into the Cause of the High Price of Gold Bullion, and to take into consideration the State of the Circulating Medium and of the Exchanges between Great Britain and Foreign Parts” (Cannan 1919: 3). The Bullion Report gave rise to a flurry of pamphlets and published letters,7 and, in accordance with the name given later to the controversy, their authors were categorised as “Bullionists” – those in favour of the report – and “Anti-Bullionists” – those against it.8 The questions raised by the report originated in the suspension of the convertibility of Bank of England notes in 1797 and had been already discussed as early as 1800. They would remain on the agenda until convertibility at pre-1797 parity was resumed in 1821. Therefore the “Bullionist Controversy” is usually considered as covering the whole period from 1797 to 1821.9 Following the editor of Ricardo’s Works and Correspondence, Piero Sraffa, I will also use the other name “Bullion Controversy” to describe the debates having occurred immediately around the Bullion Report, that is, from 1809 to 1811.10 Ricardo himself used the expression in a letter of 26 January 1818 to Hutches Trower:

Every thing that has since occurred has stimulated me to give a great deal of attention to such subjects: first, the Bullion controversy, and then my intimacy with Mill and Malthus, which was the consequence of the part I took in that question.

(VII: 246)

The Bullionist Controversy has been for many commentators the most important debate in the history of monetary thought of all time. For Viner (1937: 120), “The germs at least of most of the current monetary theories are to be found in it”, and for Hayek (1939: 37), it “may still be regarded as the greatest of all monetary debates”. Comparing two periods separated by more than one century, Schumpeter (1954: 692) notes:

The report of the Cunliffe Committee that recommended England’s return to gold at pre-war parity in 1918 displayed little, if any, knowledge of monetary problems that was not possessed by the men who drafted the Bullion Report.

Summing up the controversy, Laidler (1987: 293) concludes that “it is hard to think of any other episode in the history of monetary economics when so much was accomplished in so short a period”.

Bullionists versus Anti-Bullionists on two practical problems

If the questions debated during the Bullionist Controversy and the answers given to them had a long-lasting importance, the opposition between Bullionists and Anti-Bullionists was nevertheless framed in terms of the practical problems of the time. Two of them were central in the controversy. First there was the question of prolonging the suspension of convertibility or not. During the first and second rounds of the controversy – in 1800‒1804 and 1809‒1811 respectively – this question traced a dividing line between the two camps: the Bullionists answered in the negative and the Anti-Bullionists in the positive. During the third round – in 1819‒1821 – that question lost its importance, the great majority of the participants to the controversy favouring the resumption of convertibility; the dividing line then shifted to the question of the conditions in which this resumption should occur. The second practical problem central to the controversy also boiled down to a question: should the Bank of England be blamed for the bad state of the currency? Again during the first and second rounds the dividing line was clear-cut: the Bullionists answered in the positive and the Anti-Bullionists in the negative. This opposition remained during the third round, the only difference being that the context of the first two was inflationist, while that of the third was deflationist.

The positions held on these two practical problems – the advisability or not of the suspension of convertibility; the defence or critique of the Bank of England – give thus an indication on the camp to which a particular author belongs. The changing conditions from one round of the controversy to another and the fact that these problems interrelated with other practical ones and several theoretical issues make however the cartography of the Bullionist Controversy more complex. A sentence introduced by Ricardo in the second edition of his Principles of Political Economy, and Taxation sums up the central issue of the Bullionist Controversy:

It will scarcely be believed fifty years hence, that Bank [of England] directors and ministers gravely contended in our times, both in parliament, and before committees of parliament, that the issues of notes by the Bank of England, unchecked by any power in the holders of such notes, to demand in exchange either specie, or bullion, had not, nor could have any effect on the prices of commodities, bullion, or foreign exchanges.

(Principles; I: 353‒4)

The Bank of England and the uncompromising Anti-Bullionists maintained that the high price of bullion and the low exchange of the pound could never be produced by Bank of England notes being in excess. Ricardo and the uncompromising Bullionists maintained that they were always produced by such an overissue. The Bullionist Controversy was then bounded by these two extreme positions, most of the participants staying in the middle and arguing that, in principle, the high price of bullion and the low exchange of the pound could be explained by an excess note issue and other causes as well; they bended to a bullionist position when they considered that, in the circumstances of the time, the former factor was mainly operative, and to an anti-bullionist position when they denied that and stressed other causes.

The Bullionist Controversy was not then a steady and recurrent fight between two organised and permanent camps, because the emergence of its central issue implied relations with other secondary questions to be settled, and this left ample room for various, if not shifting or contradictory, opinions. However, on two particular occasions, when it was necessary to legislate on the monetary system, this variety of opinions did not preclude a clear-cut outcome. In 1811, the House of Commons rejected the report prepared by its Bullion Committee, which made a diagnosis and proposed remedies focusing on the necessity to regulate the note issue in view of resuming convertibility. That rejection was clearly a victory for the Anti-Bullionists. In 1821, Parliament decided on the restoration of the pre-1797 monetary system, including note convertibility into specie at the old parity and absence of any note-issuing rule. The Bullionists-versus-Anti-Bullionists reading key, manufactured under inconvertibility, no longer applied to the outcome of this debate on a regime with convertibility, although it still did in its uncompromising variant, which referred to both convertibility and inconvertibility: in 1821 as in 1811, the Bank of England won the field over Ricardo.

A central question: the role of note-issuing in monetary disorder

If the complexity of the interrelations between the central question of the Bullionist Controversy – the role of note-issuing in monetary disorder – and other questions somewhat obscures the historical account of the debates, it also explains the lasting theoretical influence of that controversy, because its analysis framed later monetary theory and policy. Before going through the successive rounds of the controversy, it may therefore be useful to delineate the interrelations between the various questions then debated.

The first question raised during the debates around the Bullion Report was: what was the exact state of the currency? Three tests were available: the rise in commodity prices, the high price of gold bullion, the low exchange rate of the pound. Each one raised specific difficulties. Assessing the rise in commodity prices implied first to distinguish between factors operating on all commodities and others specific to particular industries, and second to distinguish among the general factors between the real and monetary causes of variation. Bullionists usually maintained that the rise in prices was mostly general and had a monetary origin, while Anti-Bullionists insisted more on real factors, general (for example, war conditions) or specific (for example, agricultural conditions).

The high price of gold bullion was considered by Bullionists as signalling a depreciation of the currency, since gold was the de facto monetary standard. By “high” they meant a market price of bullion above the mint price of coined gold (£3. 17s. 10½d. per ounce of standard gold). The Anti-Bullionists objected that, convertibility having been suspended, gold was no longer the monetary standard, so that its price was not an indicator of the state of the currency. Bullion was then for them a commodity like any other, and its high price could be explained by real factors affecting the supply of and the demand for it, such as changes in the world production of the metal, demand on the Continent, domestic demand for hoarding purposes or for export (in the latter case, one had to look at the state of the foreign balance).

The low exchange of the pound raised first a difficulty of measurement. By “low” everybody meant: below the metallic par of exchange with the foreign currency considered. In contrast with the price of coined gold which was legally fixed – and could be used as the reference to ascertain the “high” price of gold bullion – there was no legal par of exchange and the benchmark against which to compare the observed exchange rate had to be computed on the basis of the metal weight contained in domestic and foreign coins. Technical difficulties then appeared: foreign coins might be debased, bear a seignorage, or have a fluctuating relation with the foreign money quoted on the exchange market (such as the Mark banco of Hamburg); moreover, the metal used as monetary standard might be different (London was on a de facto gold standard, Hamburg on a silver standard, Paris on a gold and silver one). A significant part of the literature during the Bullion Controversy was devoted to sort out whether and by how much the exchange was “low”. This was not only important to assessing the state of the foreign balance but also to explaining it. For Bullionists, a high price of bullion and a low exchange were two sides of the same coin, which reflected a depreciation of the currency; the divergence with a normal situation was then expected to be of the same order of magnitude with both indicators. For Anti-Bullionists, the two indicators had to be treated separately, since each one reflected the operation of specific factors; a significant difference between the measures of bullion being high and the exchange being low strengthened their position.

When, leaving aside commodity prices, attention could be concentrated on the high price of gold bullion considered as a monetary indicator and on the appropriately measured low exchange, some further steps were still needed to approach the central issue of the controversy. If the high price of bullion reflected the degraded state of the currency, then which currency? The Bullionists insisted that the depreciation concerned Bank of England notes, and they disqualified any influence of other circulating mediums: specie (which was not degraded, and would soon completely disappear from domestic circulation), country bank notes (whose quantity was ultimately regulated by Bank of England issues), credit instruments (which were not part of the currency). These disqualified elements were of course debated. As for the low exchange, its monetary interpretation by the Bullionists gave rise to the Anti-Bullionist objection that real factors provided the explanation, such as bad harvests in Britain (leading to abnormal food imports) and/or war transfers.

Finally, one could get to the central issue. If note-issuing by the Bank of England was suspected of being responsible for the depreciation of the currency, how did this occur? The Bullionists put forward two complementary elements. On the one hand, the check on overissue imposed by convertibility – notes issued in excess would return back to the Bank of England and drain its reserves, forcing it to contract the issues – had disappeared in 1797, freeing the Bank of England from any constraint. On the other hand, the Bank of England had not adopted the only note-issuing rule which could have prevented an overissue under inconvertibility, that is, watching the price of bullion and the exchange rate. The answer of the Bank of England and of the Anti-Bullionists who supported it was also twofold. On the one hand, there were plenty of examples, before and since 1797, of an expansion of the note issue being concomitant to a decline in the price of bullion and/or an improvement of the exchange, or the symmetrical situation, so that the alleged monetary indicators had to be explained by other factors, mainly the foreign balance. On the other hand, an overissue was impossible, as long as – which was the practice claimed by the Bank of England – notes were issued by discounting good commercial paper generated by actual activity – what would be later called the Real Bills Doctrine. If too many notes had been issued, it could then only be at the request of the government, for which the Bank of England was not to blame.

Not many participants in the Bullionist Controversy were able to grasp the interrelations between all these questions and to weave them into a consistent whole. Two figures emerge from that difficult exercise: Henry Thornton and David Ricardo.

Considering the novelty of inconvertibility in England and the negative evaluation of previous foreign experiments of the kind – such as the system of assignats in Revolutionary France – one would have expected the Bank Restriction Act of 3 May 1797 to generate immediate debates, but Sir Francis Baring’s Observations in favour of the suspension (see below) had no opponents. The main reason was that at first there were no adverse consequences of suspension. It was only in 1800 that the general price increase and the decline of the exchange rate of the pound led to the expression of diverging opinions. This was the first round of the Bullionist Controversy, which, considered from the point of view of analytical achievement, culminated with the publication in 1802 of Henry Thornton’s Paper Credit of Great Britain.

1.4 The first round of the Bullionist Controversy (1797‒1803)

The search for analytical foundations

In 1797 Sir Francis Baring, founder of the merchant bank wearing his name, published two pamphlets, Observations on the Establishment of the Bank of England and on the Paper Circulation of the Country, followed in the same year by Further Observations. He stressed the pivotal role of the Bank of England in the English banking system, especially when a run on country banks became contagious and jeopardised the system as a whole – the very situation which had led to the suspension of convertibility of Bank of England notes. In such a case, the responsibility of the Bank of England was to be the “dernier resort” in the money market – an expression borrowed from juridical French and which would later flourish in the literature under the phrasing “lender of last resort”. Baring was confident in the directors of the Bank of England for having performed that role in an appropriate way during the crisis of 1793‒1797. He nevertheless considered that the suspension of convertibility – which he found justified – called for improvements in the monetary system, such as the Bank of England notes becoming legal tender11 and their issuing being regulated. Baring’s positions in 1797 were thus a mix of what would later be anti-bullionist – the defence of the suspension and of the Bank of England – and bullionist – the necessity for guidelines for Bank directors’ behaviour. This ambivalence was an illustration of the absence of controversy at the time.

The beginning of the Bullionist Controversy is generally associated with the writing in November 1800 of Walter Boyd’s Letter to the Right Honourable William Pitt on the Influence of the Stoppage of Issues in Specie at the Bank of England, on the Prices of Provisions and Other Commodities; the letter was published in February 1801. William Pitt was then Prime Minister, and Boyd wrote to him to present his views about the inconvertible monetary system which was in force since 1797. According to Boyd, the crucial point was that, having been released from the obligation to reimburse its notes in specie, the Bank of England in its search for profits had increased the circulation of its notes by 30 per cent, hence the amount of the circulating medium since country banks’ issues and London banks’ deposits were limited by the availability of Bank of England notes. This overissue was responsible for the depreciation of the currency, which manifested itself in the general increase in prices. Although the exchanges resulted from various causes, it was likely that they had turned against the pound because of this excess circulation. The reason was that, while under convertibility the Bank of England was compelled to restrict its issues when it suffered an external drain, under inconvertibility it did not face such a drain and continued increasing its issues, fuelling the domestic depreciation and the deterioration of the exchanges. The solution to the bad state of the currency was thus to dispense with the forced paper-money which had been implemented since 1797 and to return to the discipline in the note-issuing behaviour of the Bank of England that had prevailed under convertibility.

In response, Sir Francis Baring published in early 1801 Observations on the Publication of Walter Boyd.12 He blamed Boyd for unduly weakening confidence in the Bank of England note. He recognised that the circulation of Bank of England notes had increased by 30 per cent in four years, but maintained that this by itself could not have produced the observed general price increase and unfavourable exchanges, which were the consequences of the war, not of Bank of England notes being issued in excess. He availed himself of the authority of Adam Smith and affirmed that notes issued by discounting bills on good security could not be in excess. The fact that Smith had considered a competitive banking system (like the Scottish one) under convertibility should have raised doubts about the relevance of the Real Bills Doctrine in a centralised system (like the English one) under inconvertibility, but this was nevertheless a widespread opinion – including among Bank of England directors and government officials – that would be long-lived, as testified by Ricardo’s later ironical remark in the quotation from Principles given above.

This opposition of views between Boyd and Baring thus reflected what would later be the dividing line between Bullionists and Anti-Bullionists. In these pamphlets, as in Boyd’s second edition of the Letter to Pitt in 1801 (which answered to Baring’s pamphlet), the controversy was, however, limited to the evaluation of the consequences of the increased circulation of Bank of England notes and to diverging opinions about the confidence which could be put in the directors of the Bank of England. The analytical foundations of the controversy were lacking. In particular, no test of the excess note issue, if any, was provided. Both Boyd and Baring contented themselves with the amount of the general price increase as being or not being a sign of that excess and with the observed absence of difference between prices of commodities quoted in coins and in Bank of England notes as being the proof that confidence in the notes had not declined.

This important analytical point of the test of an excess note issue was emphasised by Peter King, who published Thoughts on the Restriction of Payments in Specie at the Banks of England and Ireland in 1803.13 He stated that the depreciation of the currency should not be judged by the general increase in prices but by two “tests”: the increase in the market price of bullion and the decline in the exchange rate of the pound:

All commercial writers have therefore agreed in considering the market price of gold and silver as the most accurate tests of a pure or depreciated currency. […] Another test of a pure or depreciated currency of great importance, though in some respects less accurate than the former, is the state of foreign exchanges.

(King 1803: 26‒7)

The true test of the depreciation of the currency was thus the positive difference between the market price of the standard in bullion and its legal price in coin, and it was valid under both convertibility and inconvertibility. Ricardo would later praise this position in a pamphlet whose title expressed the same idea: The High Price of Bullion, a Proof of the Depreciation of Bank Notes (III: 51).

Another author contributed to the first round of the Bullionist Controversy on the bullionist side by introducing a statement which would have a great importance at the beginning of the second round, especially in Ricardo’s writings. In his Remarks on Currency and Commerce published also in 1803, John Wheatley stated that the unfavourable exchanges could have only one cause – excess of notes – contrary to common opinion that recognised the possibility of other causes besides this one. Following Viner (1937: 106), commentators thus usually label Wheatley an “extreme Bullionist” – a qualifier also given to Ricardo for the same reason.

Both King and Wheatley wrote their pamphlets as a critique of a book published in 1802, whose author – Henry Thornton – outstripped all participants to the first round of the Bullionist Controversy.

Thornton’s Paper Credit of Great Britain

The publication in 1802 of Henry Thornton’s An Enquiry into the Nature and Effects of the Paper Credit of Great Britain marked a breakthrough on the questions raised since the beginning of the Bullionist Controversy.14 In contrast with Hume’s vision that was the reference of the previous participants to the debates, according to which the same adjustment mechanism applied in any circumstance, a first contribution of Thornton was to make a distinction between various cases, which required different analyses. One should avoid confusing an external shock, which disturbed foreign economic relations, and a domestic one, due to a defect in the working of the monetary system. Moreover, one should separate normal times, in which the adjustments operated mechanically, and special circumstances, which might justify active interventions.

Two main sources of monetary instability may be distinguished in Thornton, and each one required an appropriate treatment. One was an exogenous disequilibrium, originating domestically (for example, a bad harvest), in foreign relations (for example, a war), or at either level (for example, a panic, provoked by a mistrust in a local bank or a fear of invasion). The problem was then to avoid a cumulative instability, and to minimise the effects of the shock until new exogenous circumstances made it disappear. Active interventions were then required: “To understand how to provide against this pressure, and how to encounter it, is a great part of the wisdom of a commercial state” (Thornton 1802: 143). Two elements pointed to the right direction, one internal and the other external. First, a contraction of the domestic circulation should be avoided, because it would impair the capacity of the exporting industries to restore the balance of trade when better times returned. As a consequence, “the bank ought to avoid too contracted an issue of bank notes” (ibid: 153), even though its gold reserves were diminishing because of the distress, and precisely to compensate the shortage of liquidity induced by the export of the metallic currency. Here lay the foundation of lending of last resort, which would be advocated by Walter Bagehot seventy years later:

For this reason, it may be the true policy and duty of the bank [of England] to permit, for a time, and to a certain extent, the continuance of that unfavourable exchange, which causes gold to leave the country, and to be drawn out of its own coffers: and it must, in that case, necessarily encrease its loans to the same extent to which its gold is diminished.

(ibid: 152)

Second, the depressive impact on the exchange of a trade deficit or of transfers abroad might be counteracted by capital inflows generated by foreign speculators who anticipated the return of the pound to its previous parity and wanted to acquire positions in that currency while it was temporarily weak:

The exchange is, in some degree, sustained for a time, which is thought likely to be short, through the readiness of foreigners to speculate in it; but protracted speculations of this sort do not equally answer, unless the fluctuation in the exchange is very considerable. If, for example, a foreigner remits money to London, at a period when the exchange has become unfavourable to England to the extent of three per cent., places it at interest in the hands of a British merchant, and draws for it in six months afterwards, the exchange having by that time returned to its usual level, he gains two and a half per cent. for half a year’s interest on his money, and also three per cent. by the course of the exchange, which is five and a half per cent. in half a year, or eleven per cent. per annum. But if the same foreigner remits money to England when the exchange has, in like manner, varied three per cent., and draws for it not in six months but in two years, the exchange having returned to its usual level only at the end of that long period, the foreigner then gains ten per cent. interest on his money, and three per cent. by the exchange, or thirteen per cent. in two years: that is to say, he gains in this case six and a half per cent. per annum, but in the other eleven per cent. per annum. If a variation of three per cent. is supposed necessary to induce foreigners to speculate for a period which is expected to end in six months, a variation of no less than twelve per cent. would be necessary to induce them to speculate for a period which is expected to end in two years. The improvement of our exchange with Europe having been delayed through a second bad harvest, it is not surprising that the expectation of its recovery within a short time should have been weakened in the mind of foreigners.

(ibid: 157)

In the first case considered by Thornton, capital inflows started when the exchange rate had fallen by 3 per cent: with the expectation of a 3 per cent gain when the exchange would return to parity six months later, added to 2.5 per cent interest on the investment in English short-term bills at 5 per cent yearly interest, the expected return was equal to 11 per cent per annum, enough to induce capital inflows (this was supposing that the interest rate abroad was below 11 per cent). In the second case, however, if the return to parity was expected only after two years, the expected return was only 6.5 per cent per annum, insufficient to trigger capital inflows. In such a situation, 12 per cent expected gain in the exchange were required, added to 10 per cent interest at a yearly rate of 5 per cent, to produce the same return of 11 per cent per annum as in the first case. This meant that the exchange rate could fall by 12 per cent before capital inflows were triggered and stopped this fall. The only way to limit the fall in the exchange rate to 3 per cent, as in the first case, was then to raise the yearly interest rate in England to 9.5 per cent. But this was impossible with the Usury Laws, which imposed a maximum interest rate of 5 per cent per annum. When two successive bad harvests delayed the return to parity during two years, the repeal of the Usury Laws would allow raising the discount rate of the Bank of England so as to attract foreign capital before the exchange rate fell too much. The importance of speculation – hence of the brake it put on the decline of the exchange and the export of gold – depended on two factors: the interest-rate differential between England and abroad (which was affected by the legislation on the maximum rate of interest), and the length of the period anticipated by foreigners for the return to parity. Here lay the foundation of uncovered interest parity (see Boyer-Xambeu 1994), which is part of modern common knowledge in international finance.

A completely different situation arose when the disequilibrium was endogenous to the domestic monetary system, for example in the case of an excess supply of bank notes. Now the threat to monetary stability was no longer an exogenous shock beyond the control of a “commercial state”, whose “wisdom” might only help to react to it. The aim was at improving the monetary system, in order to prevent the endogenous depreciation from appearing. The solution had then to be found elsewhere, and again two elements might help, one internal, the other external. First, in a system where the volume of bank notes issued was endogenously driven by the demand for them, which depended itself on the difference between the expected return on investment and the interest rate at which one could borrow from the bank, overissue might be avoided if the Bank of England was allowed to increase its discount rate as much as necessary (which required repealing the Usury Laws), and was strongly induced to do so (which justified a controlled monopoly of issue). Second, the external constraint imposed by gold bullion being “the larger article serving for the commerce of the world” provided a criterion to judge whether bank notes were or were not in excess. In a domestic monetary system where convertibility ensured that gold coins and bank notes were “interchangeable”, any excess supply of bank notes which depressed their value in terms of goods also depressed the value of the coin. If the purchasing power of bullion abroad remained unchanged – hence its purchasing power in England, which could not depart from its world purchasing power, because of international arbitrage – the double value of gold (lower in coin than in bullion) was reflected in its double money price in pounds (the market price of bullion being higher than the mint price).

By reducing the metallic circulation, this export of gold compensated the excess quantity of bank notes; hence it was a factor of monetary stabilisation (at the domestic level it depressed the market price of bullion and at the foreign one it rectified the exchange), unless the Bank increased its issues at the same time. Although the absolute level of these issues was impossible to determine, the excess of the market price of bullion over the mint price then provided a criterion for their required variation: they should be reduced whenever this divergence became abnormal.

An analytical conclusion emerged from the distinction between exogenous and endogenous sources of monetary instability. If both cases called for the repeal of the legislation imposing a maximum interest rate, they differed diametrically about the expected behaviour of the Bank of England: an exogenous shock might require expanding the issue (lending of last resort), while an endogenous fall in the value of money imposed contracting it.

This sophisticated analysis would allow Thornton to adapt his diagnosis and remedies to changing circumstances, without facing contradiction. In 1802, his analysis of the crisis of 1797 insisted on exogenous causes (bad harvests, war transfers), which had generated an adverse foreign balance: the causality ran from an external fall in the value of money (a decline in the exchange rate) to a domestic one (the increase in the market price of gold bullion). Instead of having contracted its note issue – precipitating the crisis15 – the Bank of England should have increased it and raised its discount rate to attract foreign capital, until unfavourable circumstances had disappeared. By contrast, as a co-author of the Bullion Report in 1810, Thornton would blame the Bank of England for having overissued in times of inconvertibility: the causality now ran from a domestic fall in the value of money to an external one, and the remedy was a contraction of the note issue and the resumption of convertibility (see below Chapter 2).

Thanks to its theoretical foundations, Thornton’s Paper Credit made thus bullionist and anti-bullionist arguments coexist. In contrast with the Bullionists Boyd, King, and Wheatley, Thornton did not blame in 1802 the Bank of England for having taken advantage of inconvertibility and issued in excess; he explained the bad state of the currency by external factors having generated an adverse foreign balance. His analysis of the effects of “a comparison of the rate of interest taken at the bank with the current rate of mercantile profit” (ibid: 254) nevertheless contained a powerful critique of what would long be a distinctive mark of Anti-Bullionism: the Real Bills Doctrine, according to which notes could never be in excess as long as they were issued by discounting bills generated by current production. Thornton pointed out that the supply of bills – hence the demand for notes – was not driven by the volume of goods under production but by the difference between the expected rate of return on the money borrowed and the actual discount rate at which the Bank of England monetised the bills – a point that would be emphasised by Wicksell nearly a century later when dealing with the relation between the natural rate of interest and the money rate of interest (see Wicksell 1934‒1935 [1901‒1906]). If this difference was large – a circumstance fostered by the legal maximum of 5 per cent imposed on the discount rate – the fact that the Bank of England only lent on good quality bills could not prevent the issuing of notes from being in excess, by comparison with what was required by the level of current production. This excess then pushed the market price of bullion upwards. Under convertibility, arbitrage triggered by the positive difference between the market price of gold bullion and the legal price at which the Bank of England was compelled to give specie for its notes led to a drain of its metallic reserves that forced the Bank of England to reduce its issues, thus correcting the excess. But this check on overissue disappeared under inconvertibility, and the depreciation of the currency then had no limit. This argument was consistent with a bullionist approach.

This ambivalence of Thornton’s Paper Credit contrasts with the tradition started by Hayek (1939) that considered that his later co-authorship of the Bullion Report marked an evolution towards a growing concern for “the dangers of a paper currency” (Hayek 1939: 56) and the necessity of a return to convertibility.16 The theoretical possibility of overissue was already present in Paper Credit, and Thornton would have no difficulty later basing on it his understanding of the situation discussed during the second round of the Bullionist Controversy. There is one Thornton indeed and it is all based on Paper Credit, but this book provides a unified theoretical foundation for both the defence of lending of last resort and the restriction of the note issue, under both convertibility and inconvertibility. The two speeches delivered by Thornton in 1811 before the House of Commons, where he defended the Bullion Report, are an illustration of that consistency. Thornton thus provides a link between the first and second rounds of the Bullionist Controversy. In this second round David Ricardo appeared.

Appendix 1: Ricardo on the bullion and foreign exchange markets

Ricardo was professionally involved neither in the bullion nor in the foreign exchange markets. However, his knowledge of their operations was sufficiently good to be used by him to invalidate the diagnoses made by his opponents and refute the arguments they derived from them. The following two examples are taken from the Bullion Controversy, one against Bosanquet, the other against Vansittart.

1. Ricardo contradicts Bosanquet on the rise of gold on the Continent

As illustrated by the title of his pamphlet The High Price of Bullion, a Proof of the Depreciation of Bank Notes, published in January 1810, Ricardo contended that the premium on gold bullion in the London market, as compared with the legal price of gold in coin, reflected entirely the depreciation of the Bank of England note (see below Chapter 2). After the publication of the Bullion Report in August 1810, which endorsed this view, Charles Bosanquet published in November of the same year Practical Observations on the Report of the Bullion Committee, in which he argued that the premium on gold bullion was not linked to the state of paper circulation in England, since the market price of gold bullion had risen on the Continent even more. The question of fact was thus whether this was true. In Reply to Mr. Bosanquet’s Practical Observations on the Report of the Bullion Committee, published in January 1811, Ricardo denied this alleged fact:

But the price of gold, we are told, has risen on the continent even more than it has here, because when it was 4l. 12s. in this country [England], 4l. 17s. might be procured for it at Hamburgh, a difference of 5½ per cent. This is so often repeated, and is so wholly fallacious, that it may be proper to give it particular consideration.

(Reply to Bosanquet; III: 195)

Ricardo did not deny that the price in English money of an ounce of standard gold was then in Hamburg £4. 17s. The practice in Hamburg was to quote gold in schillingen Vlams banco (“Flemish schillings” in Ricardo’s text; Fs. hereafter), each of them being divided in 12 groten and with 2⅔ schillingen Vlams banco being equal to one Mark banco of the Bank of Hamburg. £4. 17s. was thus the arbitrated price of an ounce of standard gold in Hamburg, that is, its price in Flemish schillings converted into English pound sterling at the ruling exchange rate applied to a bill drawn in Hamburg on London. This calculation was always made by the London bullion trader to determine the profit he could make

by sending an ounce of bullion to Hamburgh, and having the produce remitted by bill payable in London in bank-notes.

(ibid: 194)

The elements of the calculation were given by Ricardo:

This ounce of gold, which we are told we sell at Hamburgh for 4l. 17s., actually produces no more than 140 schillings 8 grotes, an advance only of 3 per cent. […] the currency of England […] being estimated on the Hamburgh exchange 28 or 29 Flemish schillings.

(ibid: 196)

One checks that the price of 140 Fs. 8 gr. (140.66 in decimals) is the equivalent of £4. 17s. (£4.85 in decimals) at the exchange rate of 29 Fs. per pound (140.66 / 29 = 4.85). To sum up: an ounce of standard gold was sold for 140 Fs. 8 gr. in Hamburg, the proceeds being “remitted by a bill payable in London” at the rate of 29 Fs. per pound, thus giving £4. 17s. This was a fact; how could it be explained? For Bosanquet, the explanation was to be found in the high level of the market price of gold bullion in Hamburg, not in London. For Ricardo the explanation was to be found in the low level of the exchange rate – a consequence of the depreciation of the Bank of England note in which a bill of exchange drawn in Hamburg was paid in London (“a bill payable in London in bank-notes”). His argument was as follows.

If the exchange had been at par (on this notion, see below the case against Vansittart), an ounce of gold bullion at the legal price in London of an ounce of gold in coin (£3. 17s. 10½d.) and exported to Hamburg would have been sold there for 136 Fs. 7 gr:

When an ounce of gold was to be bought in this country at 3l. 17s. 10½d., and the relative value of gold was to silver as 15.07 to 1, it would have sold on the continent for nearly the same as here, or 3l. 17s. 10½d. in silver coin. In Hamburgh, for example, we should have received in payment of an ounce of gold 136 Flemish schillings and 7 grotes, that quantity of silver containing an equal quantity of pure metal, as 3l. 17s. 10½d. in our standard silver coin.

(ibid: 195‒6)

The calculation is thus: at a mint ratio of 15.07, an ounce of standard gold is legally equivalent to 15.07 ounces of standard silver, which in Hamburg have a price of 136 Fs. 7 gr. Since, as observed above, the same ounce of standard gold was now valued at 140 Fs. 8 gr., this meant that the rise in the price of gold bullion in Hamburg had been 3 per cent (“an advance of only 3 per cent.”), much less than the rise of 18 per cent in London (£4. 12s. as compared with £3. 17s. 10½d.).17 Not only was Bosanquet wrong in his diagnosis – gold bullion had risen much more in London than in Hamburg – but the explanation of the acknowledged £4. 17s. price of gold bullion in Hamburg was to be found in the fall of the exchange rate: it now cost 24.5 per cent more (£4. 17s. as compared with £3. 17s. 10½d.) to remit the proceeds of the export and sale in Hamburg of an ounce of gold bullion than it would have if the Bank of England note in which the bill was paid in London had not been depreciated relatively to gold:

The currency of England being now depreciated, and being estimated on the Hamburgh exchange at 28 or 29 Flemish schillings, instead of 37, the true value of a pound sterling, 140 schillings 8 grotes, or 3 per cent. more than 136s. 7g. will now purchase a bill payable in London in Bank notes for 4l. 17s.; so that gold has not risen more than 3 per cent. in Hamburgh, but the currency of England, on a comparison with the currency of Hamburgh, has fallen 23½ per cent.

(ibid: 196)18

Ricardo concluded that, against Bosanquet, he had thus established:

The truth of my assertion, that it is not gold which has risen 16 or 18 per cent. in the general market of the world, but that it is the paper currency in which the price of gold is estimated in England, which alone has fallen.

(ibid)

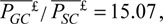

Ricardo did not say where the figure of 136 Fs. 7 gr. on which his calculation rested came from. The only indication he gave in the quotation above obscures the matter. One could believe that the exchange rate of 37 Fs. per pound, “the true value of a pound sterling”, is the par of exchange, that is, the rate that would apply in the situation where an ounce of gold bullion exported to Hamburg would exchange there for 136 Fs. 7 gr. But if £3. 17s. 10½d. exchange for 136 Fs. 7 gr., the rate of the pound is 35 Fs. 1 gr., not 37. That this rate of 35 Fs. 1 gr. was the par of exchange was confirmed by Ricardo himself in one of the observations he made on Vansittart’s propositions during the Bullion debate in May 1811 (see below):

The real par of exchange between England and Hamburgh when the relative market value of gold and silver, agrees with the relative mint value viz as 1 to 15.07, is 35/1.

(III: 417)

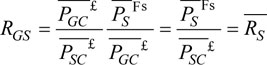

Checking the figures used by Ricardo requires a little calculation. First, one needs to correct a slight error made by Ricardo about the mint ratio (as shown in this quotation, he made the same mistake in his case against Vansittart). As mentioned in the text of Chapter 1 above, the mint ratio in England was 15.21 and not 15.07. The figure of 15.07 was obtained by dividing the legal price of an ounce of standard gold in coin (£3. 17s. 10½d.) by the legal price of an ounce of standard silver in coin (62d.). But one neglected thus that the fineness of standard gold (22/24, that is, 916.667/1000) was below that of standard silver (222/240, that is, 925/1000). Taking this difference into account gave a mint ratio of 15.21 instead of 15.07. One ounce of standard gold bullion was thus legally equivalent to 15.21 ounces of standard silver bullion, which contained 14.06925 ounces of pure silver, or, with one ounce = 31.1035 today’s grams, 437.6029 grams of pure silver. A Cologne marco (the unit of weight used in Hamburg) being equal to 233.855 grams, this gave 1.8713 marco, hence, with one marco of pure silver being valued 27 Mark 10 Schillinge banco by the Bank of Hamburg, 51.6935 Mark banco. On the basis of the equivalence between one Mark banco and 2⅔ schillingen Vlams banco (“Flemish schillings”), this gave 137.8665 Fs., that is, 137 Fs. 10 gr., instead of 136 Fs. 7 gr. as indicated by Ricardo. The difference is small (0.9 per cent) and may be explained by slightly different definitions of the measures of weight, the English ounce and the Cologne marco. This calculation thus confirms Ricardo’s knowledge of the practice of the time and still strengthens his conclusions: according to it, the rise in the price of gold bullion in Hamburg was actually 2 per cent (140 Fs. 8 gr. as compared with 137 Fs. 10 gr.), still lower than the 3 per cent acknowledged by him (140 Fs. 8 gr. as compared with 136 Fs. 7 gr.).

Another phrase by Ricardo shows that he was not only aware of the intricacies of the international bullion market but also of those of the foreign exchange market.19 One of the much-debated questions during the Bullion Controversy was the explanation of the acknowledged fact that the export of gold had accelerated during the past few years. The answer by Bosanquet was simple: since the price of bullion was 5½ per cent higher in Hamburg than in London, it was profitable to export it. Again, the monetary situation in England was not to blame, but the high price of gold on the Continent. This Ricardo denied, first because the cost of exporting gold in these troubled times was higher than the expected gain in price, and second because this expected gain was actually smaller than the percentage difference between the prices of gold bullion in Hamburg and London:

The exporter of an ounce of gold purchased here at 4l. 12s. would at least have had to wait three months before he could have received the 4l. 17s. because after the gold is sold at Hamburgh the remittance is made by a bill at 2½ usances; so that allowing for interest for this period he would actually have obtained a profit of 4¼ per cent. only; but as the expence of sending gold to Hamburgh is stated in evidence to be 7 per cent., a bill would at this time have been a cheaper remittance by 2¾ per cent.

(Reply to Bosanquet; III: 198)

In Hamburg, the bills on London were “long”, meaning that they were paid in London after a period of two and a half months. The exporter of gold bullion had thus either to wait until the bill came due before obtaining the sum remitted from Hamburg, or to have the bill discounted in London if he preferred to get the money immediately after reception of the bill. In both cases, he faced a cost of interest equal to 1¼ per cent (5 per cent yearly interest during two and a half months plus a few days for intermediation). The expected profit was thus 4¼ per cent instead of 5½, still lower than the 7 per cent cost in transport and insurance of the metal. An export of gold by arbitrage was thus not profitable. A corollary was that any debt contracted in London for payment in Hamburg could be advantageously discharged by selling in Hamburg a bill on London at a 4¼ per cent discount, rather than by exporting gold at a cost of 7 per cent.

2. Ricardo contradicts Vansittart on the state of the exchange with Hamburg in 1760

The issue was here whether the greatly unfavourable exchange at the time of the Bullion Controversy was an unprecedented phenomenon – to be related to the inconvertibility of the Bank of England note, as contended by Ricardo – or had been observed in the past, under convertibility. During the debate in Parliament in May 1811, Nicholas Vansittart moved seventeen counter-resolutions challenging the Bullion Report (see below Chapter 2). The fifth one read:

That such unfavourable exchanges, and rise in the price of Bullion, occurred to a greater or less degree during the wars carried on by King William the 3d. and Queen Ann; and also during part of the Seven years war, and of the American war.

(III: 416)

In his manuscript “Observations on Vansittart’s Propositions respecting Money, Bullion and Exchanges”, Ricardo commented on that proposition:

During the seven years war the gold coin then the principal measure of value had become debased which will account for the price of gold having occasionally been as high as £4. 1. 6. The exchange was, though as low as 31.10 in 1760, never below the real par. The relative value of gold and silver was in the market at this time as 14 to 1. Gold was a legal tender in England and a pound sterling in gold was probably of less value in the market than the silver in 31/10 of Hamburgh. The real par of exchange between England and Hamburgh when the relative market value of gold and silver, agrees with the relative mint value viz as 1 to 15.07, is 35/1, – consequently when the relative value is as 1 to 14 the real par is 32/7. Now if we take into our consideration the debased state of the English coin in the year 1760 it is probable that the exchange when at 31/10 was really favourable to England.

(ibid: 417)