“The excitement has now died down to a large extent, and much of the chagrin has vanished, too,” commented the Washington Post on the first anniversary of Sputnik. The five-part series, entitled “Sputnik plus One,” portrayed the American people as having recovered from the uproar that followed the first Soviet satellite a year before. Hanson Baldwin, writing in the New York Times, agreed, as he noted that public opinion was much less frantic a year later. In part, the Eisenhower administration had reassured the nation by the actions it had taken; in part, new issues such as the forced resignation of White House Chief of Staff Sherman Adams and a serious crisis in the Formosa Straits over Quemoy and Matsu had replaced the post-Sputnik concerns.

The belated American successes in space had helped reduce public anxiety. With ARPA and NASA, the Eisenhower administration had created vigorous new agencies to plan and conduct space activities. A year after Sputnik, the United States had caught up with and passed the Soviets in space, launching a total of four satellites (three Explorers and one Vanguard) compared to the three Sputniks. On October 4, 1958, three American satellites were still circling the earth, while only the last Sputnik remained in orbit. Yet the Soviets had used more powerful rockets, capable of delivering objects weighing as much as a typical American automobile into space; Sputnik III was eighty times heavier than Explorer III.1

In the all-important missile race, the American people still believed the Russians had a slight lead. A Gallup poll released on October 3, 1958, revealed that 40 percent of those questioned thought that the Soviet Union was “ahead in the field of long-range missiles,” compared with 37 percent who thought the United States led. Hanson Baldwin felt that the Russian lead had been exaggerated after Sputnik and that a year later “across the board the United States is probably abreast or ahead of the Soviet Union.” But he and others noted a sense of complacency within the administration and a tendency to give too much weight to budgetary concerns. Critics, notably Democrats, sensed that President Eisenhower had been hurt politically by the post-Sputnik concern over national defense; “his halo had slipped,” one commented. As a result Democrats were hoping to make significant gains in the upcoming congressional elections.

Education proved more difficult to evaluate. The Washington Post commented on the way that the “beep-beep-beep of Sputnik” had become “a rallying-cry for critics of American education.” But many felt that the National Defense Education Act was disappointing and that American schools a year later remained “more or less what they were.” At the same time, there seemed to be greater attention paid to “intellectual values” and encouraging signs of greater emphasis on the teaching of math, science, and foreign language at the expense of “frill” electives. Although some critics were hoping that the Russians would be the first to land a rocket on the moon in order to stimulate greater public efforts for education, a majority of Americans did not share this concern. A Gallup poll indicated that a surprising 68 percent felt that the United States had “a better educational program” than the Soviet Union, and only 19 percent disagreed.

Overall the American people seem to have regained their composure a year after the initial panic over Sputnik. “Some are indifferent,” commented the Washington Post, “perhaps a majority are complacent, but a vigorous minority are disturbed and apprehensive.” It was this lingering feeling that the United States had not done enough to meet the Soviet challenge that cast doubt on the nature of Eisenhower’s leadership. In all the post mortems on Sputnik, the question of whether the administration had done enough kept recurring. Hanson Baldwin referred to both “the limited imagination and the limited budget of our space program,” while Chalmers Roberts concluded “Sputnik plus One” with a wistful observation: “The great question today is: Will America get the leadership it needs?”2

Eisenhower’s determination to play down the feeling of a race with the Soviets became clear in his conduct of space policy in the fall of 1958. With NASA due to begin functioning on October 1, 1958, Killian began making preparations for the first meeting of the new Space Council in late September. Although it was to be modeled after the National Security Council, the president recommended that the new body meet only once a month, not weekly like the NSC. He told Killian that he did not want the members of the council to play too active a role; he viewed them as a board of directors whose job was simply to review and approve the policies set forth by NASA administrator Keith Glennan.

At the first meeting of the Space Council, on September 24, 1958, the president read a statement prepared by Killian that spelled out his views. “I shall look to this Council,” Eisenhower began, “for advice on the broad policy aspects of our national aeronautics and space program.” The group quickly agreed to meet once a month, primarily to listen to and comment on items presented by NASA Director Glennan. The council’s main purpose would be to clear up ambiguities in the space program, particularly by settling jurisdictional disputes regarding what would be considered peaceful space activities assigned to NASA as opposed to military projects to be retained by the Pentagon’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA).3

Most of the discussion centered on plans for a large rocket booster, in excess of one million pounds thrust, that would be needed for deep space flight such as sending men to the moon. ARPA had already asked Wernher Von Braun’s team at the Army Ballistic Missile Agency (ABMA) at Huntsville to begin designing such a huge booster. Von Braun began to develop plans to cluster eight Jupiter rockets together to achieve an engine capable of delivering more than a million pounds of thrust. Eisenhower expressed a preference for placing this key project under NASA’s control, but he agreed with the Space Council’s decision to let the two agencies try to work out their own arrangement, with the council to make the final decision if they reached a stalemate.4

On October 1 the White House released an executive order establishing NASA by giving it authority over three former NACA research laboratories as well as over most of the nation’s existing space programs, including ARPA’s Explorer satellites and planned moon probes as well as the Navy’s Vanguard effort. NASA was put in charge of the million-pound booster, but the question of shifting both the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) at Cal Tech and Von Braun’s ABMA from the army to NASA was left open for negotiation. The order also confirmed the transfer of $ 117 million from the Pentagon to NASA in the 1958 budget to pay for these space programs.5

The new space agency now was in charge of two of the nation’s three major space activities. The first, earth satellites, was already beginning to lose public interest now that the United States had overcome the initial Soviet advantage. Vanguard had achieved just one successful launch, a tiny three-and-a-quarter-pound sphere that was predicted to orbit the earth for two hundred years. After a seventh Vanguard attempt failed in late September, NASA suspended the program while it studied the reasons for the lack of success of the original American satellite effort. Despite a failure in August, NASA continued the Explorer program, which used Von Braun’s reliable Jupiter-C booster to send up satellites designed to gain more information about the risks and hazards astronauts would encounter in the first manned space flights.6

There was far more interest in NASA’s second area of responsibility, lunar probes to be conducted by the air force and the army. After the failure of the first moon shot in August, the president worried about how to “avoid undue suspense and expectations” when Glennan briefed the cabinet on October 9 on plans for a second lunar probe designed to place a television camera in orbit around the moon. Recalling wistfully the secrecy surrounding the wartime Manhattan Project, Eisenhower suggested referring vaguely to “space probes” and disguising the actual purpose of the flight “unless and until it should be a success.”

Pioneer I, launched by the air force from Cape Canaveral on October 11, proved to be a near miss that captured the public’s imagination. A four-stage rocket powered by a modified Thor with an eighty-five-pound instrumented pay load, the lunar probe performed well, reaching a top speed of 23,450 miles per hour and traveling nearly eighty thousand miles into space, thirty times farther than any of the Russian or American satellites. It went one-third of the way to the moon, missing its goal only because of a trajectory that was slightly too shallow to enable it to escape from the earth’s gravitational pull.

American space enthusiasts hailed Pioneer I as an “unprecedented shot.” “The all-important fact,” claimed Time, “was that the bird had plumbed the black beyond and had climbed to unheard-of-heights.” Missile-builder Simon Ramo put it more succinctly: “What we gained this weekend was a few seconds on infinity.” Life presented five pages of color pictures on Pioneer I, which it called “a priceless package of Liliputian instruments,” the product of the “best brains of the Air Force.” The editors talked of the important data gathered on the limits of the Van Allen radiation belts, which indicated that manned space flight would be possible. Despite the fact that Pioneer I did not reach the moon, Life called the launch “historic,” proclaiming that “its record-setting flight must be counted not a failure but a major triumph of man.”7

The near euphoria over Pioneer I quickly faded as subsequent American lunar probes failed to reach their goal. In early November Pioneer II, the final air force effort, climbed to an altitude of only one thousand miles before its third stage failed to ignite. Traveling at sixteen thousand miles per hour, the instrument package fell back into the earth’s atmosphere over Central Africa and quickly disintegrated. The army’s first effort at a lunar probe came in early December. Pioneer III, a sixty-ton, four-stage rocket powered by a Jupiter IRBM and carrying a thirteen-pound payload, fared better, traveling some sixty-six thousand miles into space but failing to go fast enough to escape the earth’s gravity. Like the first Pioneer, the army’s moon probe did bring back valuable information about the radiation belts surrounding the earth.

The public interest in these lunar probes reflected the desire to have the United States beat the Russians to the moon and thus wipe out some of the lingering aftereffects of Sputnik. American confidence suffered another setback in early January when Luna I, the first Soviet lunar probe, flew within thirty-two hundred miles of the moon before going into solar orbit. Despite the Russian failure actually to reach the moon, Luna I maintained the Soviet lead in space by becoming the first man-made object to escape the earth’s gravitational pull.8

ARPA, rather than NASA, retained control over the third U.S. space effort, the reconnaissance satellite, which Eisenhower felt was far more important than either scientific satellites or lunar probes. Worried that continued U-2 overflights of the Soviet Union might create an international incident, ever since the first Sputnik the president had looked forward to the day when American satellites would replace the vulnerable spy plane. He and his advisers had defended the high cost of the WS-117L program, allocating $186 million in the 1959 budget, nearly as much as the total for all NASA activities. Defense Secretary Neil McElroy had put the case for the reconnaissance satellite most forcefully, terming it “vital to the security of the United States.” “The prior warning which the reconnaissance satellite might well provide,” McElroy believed, “could save the country from heavy destruction in the event of a Soviet nuclear attack.”

Given the importance of a spy satellite to American security, the president decided in February 1958 to put the CIA in charge of the effort, now code-named Corona. The air force, operating under orders from ARPA, would develop a special Thor booster to place a CIA-designed capsule, complete with camera, into a polar orbit that would offer the best possible view of Soviet territory from space. As the time for the first launch neared, ARPA decided to give out a cover story to the press. On December 3, 1958, the Pentagon announced Project Discoverer, described as a “long-range satellite program aimed at placing mice, monkeys, then man in space.” Launched from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California rather than Florida’s Cape Canaveral, these satellites would weigh about a thousand pounds, lighter than Sputnik III but much heavier than the American Explorers. Despite the scientific cover, experts speculated that the California site would permit the launch of reconnaissance satellites that required a polar orbit.9

Members of the President’s Science Advisory Committee worried about what one termed the “political vulnerability” of the American spy satellite. O. G. Villard of the Space Science Board of the National Academy of Sciences objected to trying to pass off Discoverer as a purely scientific experiment. People were bound to learn its real purpose, he claimed, favoring instead a forthright policy of disclosing its reconnaissance mission. Another scientist suggested offering all the data gathered to the United Nations as part of a claim to a policy of freedom of space.10

The president was more concerned with the slow pace of Discoverer. The first flight, scheduled for January 1958, ran into technical difficulties and did not take place until late February. Meanwhile Eisenhower grew increasingly worried about the U-2 flights. Noting that the Russians were tracking these overflights with radar, he told his Board of Consultants on Foreign Intelligence Activities on December 22, 1958, that he wondered “whether the intelligence which we receive from this source is worth the exacerbation of international tension which results.” Two months later, he informed advisers pressing for more U-2 flights that he felt they represented “undue provocation.” “Nothing,” he added, “would make him request authority to declare war more quickly than violation of our air space by Soviet aircraft.” Referring obliquely to Discoverer, he said this project was coming along “nicely,” and he would prefer to avoid U-2 overflights until the “new equipment” was ready. Unfortunately, as Donald Quarles pointed out, the reconnaissance satellites would not be ready for another eighteen months to two years.11

Quarles was very accurate in his prediction. The early Discoverer flights met with difficulty after difficulty; first the satellites did not go into the proper orbit, then the air force had trouble capturing the film packages that floated back to earth by parachute. Finally, in August 1960, Discoverer flights 13 and 14 succeeded in taking very revealing pictures of Soviet territory. By that time, however, the international incident that Ike had feared had already occurred when the Soviets shot down Francis Gary Powers’s U-2 on May 1, 1960, leading the president to suspend the overflights. The success of Project Discoverer meant there was only a three-month gap in aerial surveillance of the Soviet Union; the spy satellite that Eisenhower had so strongly backed since Sputnik proved invaluable in protecting American security in the early 1960s, the period when the missile gap was supposed to be at its height.12

While NASA began to take control over all space activity except the spy satellite, two issues developed that required action by the Space Council. The first was the question of whether or not to transfer the army’s two space activities—the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the Army Ballistic Missile Agency—to NASA. Glennan thought he had worked out an agreement with Deputy Secretary of Defense Quarles for NASA to acquire both, but Secretary of the Army Wilber Brucker fought hard to hang onto the Huntsville operation. Leaks to the press, including a threat by Von Braun to quit if NASA took over his team, placed great pressure on the administration. The president expressed disgust at bureaucratic maneuvering and “the lack of any spirit of give and take” over this issue. Although he thought NASA should take charge of both activities, he accepted a compromise worked out between Glennan and Brucker that transferred the JPL to NASA but kept ABMA under army control for a year, with work on the million-pound booster at Huntsville to be done under contract to the space agency. On December 3, 1958, the Space Council formally accepted this solution.13

The second item on the agenda was a NASA request that Project Mercury, the plan for manned space flight, be given “highest priority.” In arguing for this step, as well as for a budget commitment of over $100 million in 1959 and 1960, NASA claimed that putting man in space was “the cornerstone on which true space exploration will be built” and was “of utmost importance to the national prestige in the eyes of the world.” In a meeting with Eisenhower prior to the formal Space Council session, Quarles and Killian both dissented on the designation of “highest priority” for manned space flight, claiming it would distort the entire priority system. The president also expressed reservations, preferring to save highest priority for “things of great importance or time-urgency.” The Space Council, nevertheless, voted on December 3, 1958, to grant Project Mercury “highest priority” in order to achieve manned orbital flights by mid-1960.

Despite this action, President Eisenhower was clearly reluctant to commit the United States to an all-out space race with the Soviet Union. Although he approved a substantial increase in NASA’s budget for 1960, from $240 to $370 million, he resisted a request by Glennan for an additional $125 million in early 1959 to develop a booster for manned flight to the moon in the 1960s. While admitting that we were in a contest with Russia for world prestige, he still felt “we must lay more stress on not going into debt by spending beyond our receipts.”14

The president’s personal reservations about manned space flight came out most clearly when he asked NASA to modify public statements on its goals. He urged “less emphasis” on ultimate applications and greater stress on “more limited objectives.” When Glennan asked him for permission to recruit members of the military for space flight, the president agreed but then asked the NASA chief not to publicize the astronauts, in order “to avoid generating a great deal of premature press build-up.” These words fell on deaf ears; soon NASA would embark on an extensive publicity campaign centering on the selection and training of the first Americans to venture into space. The president, however, remained skeptical of the space race between the United States and the Soviet Union that had begun with Sputnik. He gave ground grudgingly to the public and congressional pressure for space spectaculars, all the while ensuring that the American response included the spy satellite that he deemed essential to national security.15

Steady progress in the American missile program in the fall of 1958 appeared to justify the president’s deliberate response to the Sputnik crisis. The main focus was on the Atlas ICBM, scheduled for deployment before the end of 1959. The air force completed the first set of tests in September, with three successful flights of the first stage at a distance of six hundred miles. The first test of the two-stage Atlas at intercontinental range, however, ended in an explosion only eighty seconds after it left the launch pad. In October McElroy informed Eisenhower that on the second try an Atlas had “accomplished a significant milestone in that the full ICBM 5500 nautical mile range was achieved.” He added, however, that accuracy was still a problem; the dummy warhead landed twenty-four miles from the target area.16

The first fully successful Atlas test at its full range of sixty-three hundred miles in late November led to new assertions that the United States had met the Soviet missile challenge. Time praised both the Air Force and Convair, builder of the Atlas, for sticking to a “schedule that was programed for maximum effort long before Sputnik.” Claiming that the Atlas was close to becoming “a real operational weapon,” the magazine concluded that “Russia has no monopoly” on the ICBM and that the American missile program was “coming and coming fast.” U.S. News & World Report agreed, asserting that even before the most recent Atlas tests the United States possessed “a formidable arsenal” of missiles. “The U.S. is clearly superior to Soviet Russia in military strength today,” the editors boasted. “That superiority rests both in nuclear weapons and the means of delivering those weapons to a target.”17

The air force, however, did not want to rely exclusively on the first-generation Atlas ICBM. Within the Pentagon it fought hard for both the more sophisticated Titan, which could be placed in a hardened silo with its storable liquid fuel, and the Minuteman, the true second-generation solid-fuel ICBM. General Bernard Schriever, head of the Ballistic Missile Division, resisted attempts to slash the Minuteman budget in half or to terminate the Titan and use its funds to pay the high cost of Minuteman development. Schriever was able to defend his ICBMs from budgetary attacks by both the army and navy. He countered with a request to expand the Titan deployment from four to eleven squadrons and thus raise the planned ICBM force from 130 missiles to 200 by 1962. The Joint Chiefs forwarded this proposal to the White House, where it would be considered in the final deliberations over the fiscal 1960 budget later in the fall of 1958.18

Final testing and deployment of IRBMs also proceeded on schedule in the second half of 1959. Although both the Thor and Jupiter experienced failures in early tests, by December both missiles had been fired successfully. The army sent a Jupiter some fifteen hundred miles downrange, while the air force Thor went nearly as far. Neither missile, however, had yet achieved a high degree of accuracy. Nevertheless, the United States went ahead with plans to place four Thor squadrons in Great Britain and continued negotiations for Jupiter bases in other European countries, primarily Italy and Turkey.19

In September components of the first Thors began to arrive in England. By the end of the year, the air force had announced the arrival of all four squadrons, some sixty missiles, at the British bases, where they were within range of Moscow. Training of English crews who would fire the Thors under American command and control took another six months. Yet even when the first squadron became operational in June 1959, the Thors were rated at only 50 percent reliability. And they remained vulnerable to a Soviet first strike, since it took at least fifteen minutes to fill them with liquid fuel prior to launch.20

It was this inherent weakness of the IRBMs, together with the prospect of early ICBM deployment, that led Secretary of Defense McElroy to announce a surprising revision in American strategic policy in November 1958. Answering a question at a press conference on when the Pentagon would make a choice between Thor and Jupiter, he replied that both would be produced, but only in limited numbers. In view of the vulnerability of IRBMs to a Soviet first strike, he felt it would be unwise to deploy additional Thors and Jupiters since “we are coming closer to the time of the operational capability of the Atlas.” Two days later, however, the State Department, in an apparent effort to reassure the NATO allies, issued a statement saying that there was “no lessening” of the American intention of basing Thors and Jupiters in Europe. “The IRBM program,” the State Department affirmed, “is best suited to strengthening that part of the free world’s defenses which lie in Europe.”

McElroy was furious at what he considered unwarranted State Department interference in strategic policy. He called John Foster Dulles on November 17 to protest, saying he found it “strange for one Dept. to put out an interpretation of another Dept.’s press statement.” The secretary of state claimed it was done without his knowledge when he was out of town; he said he was “disturbed” and agreed that “it never should have happened.”21

The press quickly noted the rift between the Defense and State Departments. The initial American response to the apparent Soviet lead in the ICBM race signaled by Sputnik had been to rely on IRBMs in Europe to protect the NATO countries from Soviet missile blackmail, as well as to add to the American bomber deterrent before the Atlas and Titan ICBMs could be deployed. The editors of the Nation and the Reporter observed that it was the United States who had taken the initiative on placing IRBMs in Europe and that the NATO allies had been quite reluctant about accepting them, fearing that the American Thors and Jupiters would be a likely target for a Soviet nuclear strike. Both journals backed McElroy, stating that it made more sense for the United States to rely on ICBMs on its own territory to deter the Soviet Union. In contrast to the State Department, they believed that removal of the American IRBMs would reassure rather than alarm Europeans.

In the ensuing controversy, some observers began to question the wisdom of relying so heavily on missiles for deterrence. William J. Newman, a Boston University government professor, argued that it was dangerous to use missiles, which reached their targets within thirty minutes, to deliver nuclear weapons. B-52 bombers were much safer, since they could be kept on aerial alert and called back hours after an initial attack order. The early missiles, moreover, were notoriously unreliable and quite inaccurate. Carl Dreher, writing in the Nation, agreed with this assessment of the lack of precision and reliability of first-generation missiles. He also favored depending on bombers for the next few years until a more sophisticated second generation of missiles came on line, the Polaris and Minuteman. He stressed the very high costs of missiles compared to aircraft and bemoaned the “gargantuan” waste involved in building duplicate ICBMs, such as the Atlas and Titan. Yet it was the huge expense that doomed all efforts at making rational choices in the missile age. “So much money is invested in a single big missile,” Dreher pointed out, “that its discontinuance is inconceivable until at least a few units have been fired in a final demonstration of its obsolescence.”22

This criticism had little effect on the administration’s decision to make ICBMs the heart of the American nuclear deterrent. On October 4, 1958, the air force opened a second major American launch complex in California both as a missile test and training ground and as a site for the deployment of the first Atlas squadron. Located on the Pacific coast 170 miles northwest of Los Angeles, Camp Cooke, an inactive army post, became Vandenberg Air Force Base. Launch pads completed in the fall of 1958 were used to test Thor and Titan missiles while work continued on facilities to house both Atlas and Titan missiles when they became operational. The new base, boasted U.S. News & World Report in December, was “the world’s biggest and most elaborately equipped missile center.”23

One great advantage of Vandenberg over Cape Canaveral in Florida lay in the way it could launch satellites in a north-south polar orbit. Vandenberg became the home base for Project Discoverer, the spy satellite operation announced in December 1958. The president originally had hoped that Vandenberg would provide greater secrecy than Canaveral, where the press regularly observed all launches from beaches only a few miles away. In November the Pentagon press office informed the White House that reporters could follow all the Pacific launches from nearby public property. Reluctantly Eisenhower agreed to the same policy followed in Florida: “giving to the press the information that they could get in any event, but giving it to them in an orderly, embargoed way, and specifying that firings which would reveal classified information will not be open to press coverage.”24

The administration went ahead with plans to deploy the first Atlas squadron at Vandenberg, but it decided to place the other twelve ICBM squadrons at air force bases in the interior of the nation, primarily in the Great Plains region. Warren Air Force Base outside Cheyenne, Wyoming, received the second group of Atlas ICBMs, while future squadrons were programmed for bases in Idaho, Washington, Nebraska, Kansas, Colorado, and South Dakota. The first Atlas squadrons were completely exposed to enemy attack; subsequent ones were placed in concrete bunkers that offered some protection. The Atlas, which took more than ten minutes to be filled with thirty thousand gallons of highly explosive RP-1 fuel and liquid oxygen, could not be fired from hardened silos. The air force relied on dispersal for minimal protection against a first strike, placing the nine missiles in a squadron in three widely scattered groups. Titan missiles, using a storable liquid fuel, were programmed for silos hardened to withstand a blast of 100 psi, with each silo located several miles away from the next.

The need to protect American missiles from a Soviet first strike slowed down the projected deployment of the first generation of ICBMs. The widely spaced concrete silos created a huge engineering complex that required nearly three years to complete from the time construction began. The first Atlas squadron at Vandenberg was deployed on open launch pads in stages in 1959, beginning with three missiles in July and only six by the end of the year. Gradually the other sites were finished, with the second Atlas squadron becoming operational in Wyoming in September 1960 and the remaining squadrons in 1961 and 1962. By December 1962 the United States had deployed nineteen ICBM squadrons—thirteen Atlas and six Titan. Minuteman became operational in late 1962, and one thousand of these second generation missiles replaced all but fifty-four of the Titans by the end of 1965.25

It is now clear that there was no missile gap in the early 1960s. The Soviet Union deployed fewer than a dozen of its first generation SS-6 missiles by 1960, fewer even than the first American Atlas missiles at Vandenberg and Warren. The year 1962, cited by Joseph Alsop as the time of maximum danger when it was believed the Russians would have 1,000 ICBMs to only 130 for the United States, was the year of the Cuban missile crisis. By that time, there was a missile gap in reverse: The United States had about two hundred ICBMs compared to fewer than one hundred for the Soviet Union. Add the nine American submarines carrying 144 Polaris missiles, and the American retaliatory advantage became overwhelming in the early 1960s.26

Eisenhower had been right all along. The missile program that he had begun in 1955 provided more than an ample margin of security for the United States as it made the transition from B-52 bombers to long-range missiles in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The president had resisted the pressures of the Gaither committee and the Democratic opposition in Congress for massive increases in defense spending to ward off a mythic Soviet threat. Yet he had proved unable to convince either Congress or the American people that there was no danger. His stubborn insistence on trying to hold down defense spending spared the nation untold billions, but he did agree to increases that he felt were not truly necessary. Eisenhower deserves high marks for protecting the national security without overreacting; as a political leader, however, he failed to persuade the American people that they were safe from foreign danger.

The congressional election of 1958 confirmed Eisenhower’s inability to reassure a worried American electorate. His personal popularity, which had fallen to an all-time low of 49 percent in the Gallup poll in April, rose to 58 percent over the summer and then fell back to 56 percent by October. Despite the fact that more than half the people gave his presidential performance a positive rating, reporters pressed him hard on his administration’s achievements as the fall election approached. Asked at an October 1, 1958, press conference to comment on America’s military position on the anniversary of Sputnik, the president cited the four satellites the United States had put in orbit in the last seven months. On missiles, he claimed the Russians had a head start as a result of lethargy in the Truman years but that his administration had greatly narrowed their lead. “I believe we have the biggest, strongest, finest body of scientists,” he concluded, “amply armed with money to do the job, and that’s that.”

Some commentators thought that Eisenhower’s rather abrupt press conference remarks had ignored political realities. “What Ike misses was that it is his own leadership, his ability to dramatize the record, that is a key issue—perhaps the only real issue—in Election Year 1958,” observed Time. Samuel Lubell noted that the Republican candidates for Congress badly needed all the help the president could offer them in the midst of a recession that gave Democrats a great advantage. Although the outcome would probably turn on local issues, Lubell felt the GOP needed to draw upon Eisenhower’s personal appeal to many voters. The people still liked Ike, he commented, although he did detect “a deep concern that Eisenhower may no longer be the master of the White House.”27

One source of political weakness was the president’s insistence on stressing fiscal restraint at a time when the Democrats were calling for more spending, both to overcome the recession at home and match the Soviet challenge abroad. Asked about the 1960 budget in mid-October, Eisenhower said he was doing everything he could “to get it down to the last cent that I think is needed” for national security and safety, adding “I believe we are spending too much money.” Referring to Democratic campaign calls for greater expenditures, the president voiced his objection to the theory “that just money alone is going to make the United States greater, stronger both at home and abroad.” The same day, he complained to a Republican group that as a result of Sputnik Congress had voted for “additional sums” that were unnecessary and had led to a big deficit, which he vowed to eliminate in the future.28

Aware that he had to answer the charge that his administration had allowed the Soviets to open up a missile gap, Eisenhower began to prepare a campaign speech on national defense. He told his speech-writers to develop the theme that the Democrats had “completely neglected” missiles and that since 1955 the administration had worked hard to narrow the Russian lead. Usually reluctant to engage in political infighting, the president said he felt a tragic error had been made and that the Republicans had to be “almost barbed” in telling this story.29

In his basic campaign speech, given first in Los Angeles on October 20 and then repeated with only minor variations to audiences in Chicago, Pittsburgh, and Baltimore later in the month, Eisenhower strongly defended his record on space and missiles. Claiming that he had inherited a “missile gap” from Truman, who spent only $1 million a year on rockets, the president pointed out that he followed the recommendations of his scientific advisers in 1955 and gave both the IRBM and the ICBM “the nation’s highest priority.” “No effort, no talent, no expense has since been spared,” Eisenhower boasted, “to speed these projects.” “Today America—and all the world—knows that in less than four years we are rapidly closing the missile gap that we inherited,” the president concluded. “The Sputniks have been matched by Explorers, Vanguards, and Pioneers.”

At the same time, Eisenhower insisted on continuing his crusade against “wasteful government spending.” He denounced the pleas of Democratic critics for even greater expenditures for missiles and other weapons. Pointing out that these “self-styled liberals” call for both more spending and tax cuts, he asked, “Now, just how gullible do these spenders think Americans really are?” Above all, he stressed America’s nuclear superiority, stating that SAC’s striking power was “beyond imagination.” In running for office, he recalled, he had “promised a strong national defense.” “No matter what the political merchants of fear and defeat would have you believe,” he told the voters, “we have kept the promise.”30

Despite the president’s fervid appeals, the electorate gave the administration a stern rebuff. The Democrats won a sweeping victory, gaining thirteen seats in the Senate and forty-seven in the House and adding five governorships to control thirty-four statehouses. As a result, those whom the president denounced as irresponsible spenders would command a 62 to 34 vote margin in the Senate and 282 to 153 in the House. Speaking to his aides, Eisenhower admitted that the Democrats had scored a “sweep” of “devastating proportions.” He realized that the figures were so bad “that there are scarcely enough Republican votes to sustain a veto.” The only bright spot, he noted, was that the defeat might unify the Republicans and end the party feuding he had found so distasteful.31

Political commentators cited many factors that contributed to the Democratic victory. Local issues, as always, played a big role in the outcome: a rejection of Secretary of Agriculture Ezra Taft Benson’s policies in the farm states, right-to-work measures in several industrial states that brought out a heavy labor vote, and the recession, which took its toll on the party in power. Liberal analyst Carey McWilliams noted the lack of any commanding national issues and called it a “landslide in a vacuum.” Life claimed that personalities played a larger role than issues and took some solace in the success of moderate Republicans like Governor Nelson Rockefeller in New York and the defeat of Old Guard Senators William Knowland in California and John W. Bricker in Ohio.

Nearly everyone, however, viewed the outcome as a reflection of the loss of national confidence in Eisenhower’s leadership. The Wall Street Journal declared it was Ike “who had the sense of direction and lost it.” The Denver Post spoke of “weak, distracted and irrationalized leadership”; the Atlanta Constitution accused the president of being “indecisive, uncertain and hesitant”; the Providence Journal claimed that “dissatisfaction” with Eisenhower “was at the root of the results.” A GOP national committeeman from Utah expressed his disgust with the president’s “aloofness from politics,” claiming that “his attitude of being above it all has made us all just a bit ashamed to be politicians.” What seemed most important of all was Eisenhower’s inability to stem a growing feeling of national uneasiness, a feeling of what the Wall Street Journal termed “impending disaster.” Samuel Lubell attributed the loss of confidence in Eisenhower to “a sense that as a nation we are beset by problems which are slipping beyond our control.”32

The president understood that he had suffered a personal defeat. At his press conference the day after the election, he appeared tired and dispirited. “It was plain that the Democratic landslide had jolted Dwight Eisenhower badly—that he found it painful to talk about,” noted Time. The president tried to put the best face on the outcome, saying that he hoped that many of the Democrats shared his concern for fiscal integrity and would join him in doing what was “best for the country.” He pointed out that the deficit was approaching a record $12 billion for the current fiscal year and warned against the possibility of inflation. Regretting that the 1958 vote marked a “complete reversal” after his reelection just two years before, he still planned to oppose excessive spending and work for the fiscal soundness of the country.33

The president may not have known how difficult a time he would have in holding down spending in the 1960 budget. Even members of his own cabinet felt that Eisenhower was obsessed with economy measures. HEW Secretary Arthur Flemming, upset by the president’s insistence on a balanced budget at a cabinet meeting three days after the election, told a sympathetic John Foster Dulles that both the Congress and the people wanted more spending. Worried about the influence of conservatives like Secretary of the Treasury Robert Anderson, Flemming suggested that Dulles and Vice-President Richard Nixon try to help Ike see the need for more creative policies.34

Knowing that the Democrats in Congress were crucial to his goal of “holding the line on our expenditures” in the 1960 budget, the president allowed Secretary of the Treasury Anderson to arrange a private meeting with a fellow Texan, Senate Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson, on November 18. Eisenhower tried to solicit LBJ’s help in curbing some of the Democrats in Congress who favored “rapid expansion in a number of military programs.” Johnson replied that many Democrats would prefer cuts in foreign aid to hold down the deficit. When Eisenhower said that during his final two years in office “his single and only concern was the welfare of the country as a whole” and asked for Johnson’s “close cooperation” in holding down spending, LBJ was noncommittal. Johnson did suggest that the president consult with Richard Russell on defense issues, and he agreed to meet with Eisenhower from time to time in an effort to achieve bipartisan consensus.35

The outcome of the 1958 elections left Eisenhower in a difficult political position. There is no evidence that Sputnik or talk of a missile gap was directly responsible for the Republican defeat.36 Yet the Soviet satellite had begun an erosion of public confidence in Eisenhower’s ability to lead the nation amid the uncertainties of the new space age. The success in launching satellites and testing ICBMs helped restore some measure of pride in American technology, but few Americans seemed to share the president’s overriding concern with fiscal restraint. Fearful that the Russians might soon regain the lead with either a moon shot or a missile breakthrough, the voters had turned to the Democrats as a better bet to deal with the unknown dangers that lay ahead.

The 1958 congressional elections undermined Eisenhower’s determination to limit defense spending. Before the Democratic victory, he tried to persuade the Pentagon to hold the 1960 defense budget to a ceiling of $40 billion, just above the current level of military expenditures. Outraged by the high cost of new weapons—airplanes and missiles that cost as much as $23 million apiece—the president warned Joint Chiefs Chairman Nathan Twining on September 29 that the military must help him achieve a balanced budget. Russian moves in the Cold War, he suggested, included “efforts to make us spend ourselves into weakness.”

Eisenhower targeted the duplication of weapons, especially missiles with similar missions, as the best place to economize. He asked his aides to prepare a “graphic chart to illustrate those duplications.” The president kept pointing out the overlap between Thor and Jupiter IRBMs and Atlas and Titan ICBMs. As new weapons were developed, he explained in his postelection press conference on November 5, it was necessary to cut out the older ones “that they are displacing.” We could not, he added, “just pile one weapon and one system of weapons on another, and so in the long run break ourselves.” Later the same day he reiterated this point to a group of scientists, calling the budget situation “intolerable unless we are able to bring expenditures in line with receipts.” We had to find “a mechanism which will disclose and assist in the elimination of duplicating weapons systems,” he insisted.37

The Pentagon failed to heed the president’s warnings. Although Secretary Neil McElroy was able to pare down the original service requests to a total of $43 billion, this figure was still $3 billion over the president’s goal for 1960. Instead of cutting back the Titan as Eisenhower and others urged, the air force recommended increasing the number of ICBMs to be deployed by 1962 from 130 to 200 by adding seven additional Titan squadrons. The navy wanted a second nuclear-powered aircraft carrier without sacrificing the Polaris program that Congress favored. Even McElroy refused to make a choice between the Thor and the Jupiter, finally deciding to produce both but in smaller numbers than the original projection.38

Faced with this apparent impasse, in late November the president summoned both his economic and military advisers to Augusta, where he was spending the Thanksgiving holiday. Secretary of the Treasury Robert Anderson and Budget Director Maurice Stans informed the president that they could balance the 1960 budget at about $77 billion if defense spending did not increase. Stans submitted a memorandum in which he stated, “It is my strong recommendation that the Department of Defense be held to a level of $40 billion [in] expenditures,” adding that in his judgment this figure “will not significantly impair the security of the country.”

Events beyond the president’s control made it impossible for him to accept this advice. Nikita Khrushchev had just begun the second Berlin crisis by threatening to turn the Soviet zone of the city over to East Germany, an action the United States objected to adamantly. With the Democrats already calling for higher defense spending, the Pentagon could now argue that the intensified Cold War required increases rather than cuts in the military budget.39

Neil McElroy opened the Augusta meeting in a conciliatory way by pointing out that he had reduced the original Pentagon request to less than $43 billion in new obligational authority and to just under $42 billion in actual expenditures for 1960. This represented an increase of only $2 billion at a time of grave national crisis. He went on to make the case for adding seven additional Titan squadrons, for a total of two hundred ICBMs, and for expanding the navy’s Polaris program from five to nine submarines. His main concession to economy was cutting back the IRBM allotment from the authorized twelve squadrons to just eight, despite the objections of the State Department.

Anderson and Stans repeated their pleas for a $40 billion ceiling for the Defense Department. They pointed out that domestic agencies had cut their original requests from $42 to $36.5 billion; if the Pentagon would only match half these reductions, the administration could balance the budget. Eisenhower asked more pointed questions, wondering why the defense budget still included so many duplicate weapons. “How many times do we have to destroy Russia?” he asked. He particularly objected to the Titan, which he considered a costly and unnecessary duplication of the Atlas ICBM. McElroy introduced a political angle when he replied that the elimination of the Titan program would cost twenty-five thousand jobs and add greatly to the unemployment rolls.

Realizing that further discussion was futile, Eisenhower adjourned the Augusta conference with a request that the two opposing sides try to work out a compromise and present it at the next scheduled National Security Council meeting in Washington on December 4. Leaving the meeting, Nathan Twining said the president was angry at the military (“full of red meat,” he told Ann Whitman, Ike’s secretary) as he insisted they go at least part way to prevent a deficit. The next day, Eisenhower vented his anger at the air force for asking for what he termed “fantastic” sums for weapons “that were still in someone’s mind.” He objected above all to the idea of funding three different ICBMs—the Atlas, Titan, and Minuteman—simultaneously. He told McElroy that “the Air Force felt, unsoundly to him, that they had to develop, produce and procure weapons all at the same time.”40

John Foster Dulles, whose failing health would prevent him from attending the upcoming NSC meeting, still tried to back the president. He told Robert Anderson that he had urged Eisenhower to resist the “terrific amount of overlapping” in new weapons and to use the savings to prevent cuts in conventional forces. Dulles, known to the public as the architect of massive retaliation, had learned from experience, notably in the Formosa Straits crisis and the Lebanon intervention, the importance of “conventional forces which we use every day in our business.” Fearful that the Pentagon would reduce ground troops to save the new weapons, he warned that “if we have nothing but nuclear warfare, we will be in a bad spot.”41

When Eisenhower returned to Washington on December 3, 1958, Maurice Stans informed him that he could achieve a balanced budget for 1960 if foreign aid could be held to $3.5 billion and defense spending to $40.8 billion. The president, stressing his “strong desire for a balanced budget,” agreed to the cut in foreign aid and asked his aides to meet with McElroy to work out a deal “along these lines.” In effect Eisenhower wanted the Bureau of the Budget and the Pentagon to split the difference on defense spending.

The NSC meeting, which finally took place on Saturday, December 6, after a two-day delay, proved to be what Ann Whitman termed a “bloody” showdown that ended in a draw. “Apparently the Navy refused to give one inch,” she commented, “and if the Navy would not give in, neither would any other service.” McElroy presented the Defense Department recommendations for seven additional Titan squadrons, four more Polaris submarines for 1960 with three more planned for 1961 (a total of twelve), and for a reduction from twelve to eight IRBM squadrons in Europe—five Thor and three Jupiter. The president withheld comment but indicated he would approve if offsetting savings could be found in other Defense Department programs. He instructed Anderson and McElroy to meet over the weekend and reach agreement on a figure, telling Ann Whitman that if they did he would consider it a “miracle.”42

Eisenhower gave in on Monday, December 8, accepting a final sum of just under $41 billion for defense expenditures in 1960. While the increase in defense spending was only about $1 billion, the new budget figures that the president approved represented a significant increase in the size of American nuclear striking forces. The number of ICBMs planned for 1962 would go from 130 to 200, while the doubling of Polaris submarines would add 112 IRBMs, more than offsetting the reduction of 60 Thor and Jupiter missiles in Europe.

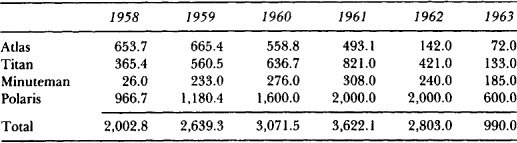

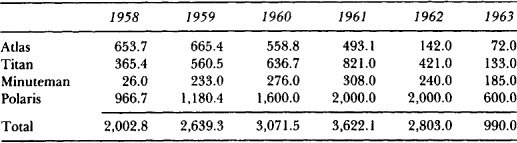

From Eisenhower’s standpoint, the most regrettable result was to build huge increases into future defense budgets. When the cost of Minuteman—which went up from just $26 million in FY 1958 to $276 million in 1960—was added in, the American ICBM budget would reach a peak of over $1.5 billion in 1961, with the accelerated Polaris program adding $2 billion more. Altogether the strategic weapons authorized by the Eisenhower administration would eventually cost the American taxpayer more than $15 billion (see Table 7).43

In giving his final approval, the president made clear his feeling of helplessness. He told Gordon Gray, who had succeeded Robert Cutler as national security adviser in the summer of 1958, that “if he were in charge [of the Pentagon] he felt that he could take $5 billion out of the Defense budget.” But since the military asserted that the programs they presented at the NSC meeting on Saturday “were essential to the national security, he had little choice but to approve them.”

TABLE 7: Table of Projected ICBM and Polaris Missile Costs (in millions of dollars)

The president was equally candid with McElroy, claiming that he had been “dragooned” into approving the Pentagon’s proposals. He expressed special distaste for the increase in ICBM squadrons, saying he still did not understand why “it was necessary to program” both Titan and Atlas missiles. He then made it clear to the defense secretary that “his approval was reluctant but was given only because he felt he had no choice.”44

One reason the president had not fought harder was his realization that, if he held the military in check during the budget process, the generals and admirals could simply have gone to Congress to ask for higher appropriations. On December 15, in a meeting with Republican congressional leaders, he went over the defense budget explaining the reasons for the increases and counseling moderation. But he admitted that, in this regard, “I’m still a reactionary.” Usually, he observed, in peacetime Congress gave the president less for defense than he asked for, but this year he expected the Democrats to insist on more funding than he thought reasonable. Urging the GOP leaders to help him hold the line, he concluded, “If anyone were to take the sum of all the estimates of requirements based on the aggregates of their fears, the result would be out of this world.”45

Thus the president knew that the nearly $41 billion figure that Anderson and McElroy finally compromised on for defense spending in 1960 was at best a minimum. In his final two years in office, Eisenhower would do all he could to hold back the tide of military expenditures, at times even refusing to spend the additional funds appropriated by Congress. Forced to ask for more than he felt was necessary for national defense, he still fought hard to achieve what he termed “security with prudence.” The vast sums spent for new weapons after Sputnik came in spite of rather than in response to Eisenhower’s strategic vision.46

On December 18, 1958, President Eisenhower made a dramatic announcement during a diplomatic dinner at the White House. The United States had just carried out Project Score, placing an entire Atlas missile into orbit around the earth; at four and a half tons, the fuel tank and engine of the rocket made it by far the largest object ever sent into space. More important, Score had put a 150-pound communications satellite into orbit, complete with a Christmas message to the world that would be beamed back to earth in the next day or two. The president took obvious pride in what he claimed “constitutes a distinct step forward in space operations.” His dinner guests shared in the mood of celebration. “Of course,” commented Ann Whitman, “everyone was elated.”

The next day the Score satellite broadcast the president’s recorded message to the entire world. “Through the marvels of scientific advance,” Eisenhower began, “my voice is coming to you from a satellite circling in outer space.” He went on to “convey to you and all mankind America’s wish for peace on earth and good will toward men everywhere.”47

The American press hailed Score as the final American answer to Sputnik. U.S. News & World Report headlined its story “4½-TON SATELLITE SHOWS WHAT U.S. CAN DO.” The editors pointed out that the latest edition of Jane’s All the World’s Aircraft ranked the United States ahead of the Soviet Union in air power and then concluded that the United States had clearly established “a lengthening lead in the space race.” Although Time admitted that sending a spent rocket into space was a stunt that served no useful scientific purpose, it nevertheless stressed the fact that Score proved that the United States had solved the critical guidance problem in launching the Atlas into orbit. The editors of Newsweek drew a contrast with the preceding year, when the Russians could boast of two Sputniks compared to the American failure to launch Vanguard. “Now the whole picture had changed,” they commented; “the ‘missile gap’ has been closed.”48

Critics were quick to point out the hollowness of these claims. The actual communications satellite that Score put into orbit weighed just over 150 pounds, far less than the 3,000-pound instrumented payload of Sputnik III. Orbiting the empty fuel tank and engine of the Atlas missile was a meaningless feat that failed to demonstrate any new technical capability. Calling Score “an extravagant propaganda stunt,” the New Republic argued that it wasted money desperately needed for genuine scientific research.49

In a sense, the critics were right. When Eisenhower first approved Project Score in August 1958, he insisted that it be kept absolutely secret, with no advance word to the press. Aware of the highly publicized failures of the first American satellite launches and moon shots, the president wanted to be able to control the public reaction. At the same time, he ordered the originating agency, ARPA, to play down the military’s role by turning the project over to NASA as soon as possible. And Eisenhower made sure that Killian was assigned general oversight of the project. The science adviser, in turn, informed the president at the outset that orbiting a spent rocket “does not represent a true technological advance vis-à-vis the Russians.” Therefore, Killian told Eisenhower, the administration “at all levels should refrain from playing up the ‘9,000 pounds in orbit’ aspect of this test.”50

In the year following Sputnik, however, Dwight Eisenhower had learned how much more important appearances were than reality when it came to space feats. In his public statements, he stressed the value of the 150-pound communication satellite in helping the people of the world exchange ideas and information rapidly. At the same time, he did nothing to discourage the euphoria of the press over the huge size of the orbiting Atlas. The American people, he had come to realize, were more impressed by spectacular deeds in space than by scientifically correct experiments.

The lesson of Sputnik was clear. The Soviets had won a sweeping propaganda victory by upstaging the United States and placing the first artificial satellite into orbit around the globe. Eisenhower had seen from the beginning that the real significance of this feat lay in demonstrating the feasibility of, and even offering a legal precedent for, a future reconnaissance satellite that could replace the vulnerable U-2. While the public worried about losing the space race and allowing the Soviets to open up a dangerous missile gap, the president concentrated on a prudent and limited expansion of American missile programs, a speedup in the reconnaissance satellite effort, a modest extension of federal aid to education in the name of national defense, and the creation of a civilian agency devoted to the peaceful exploration of outer space. Yet in achieving these goals, he had failed to quiet the fears of the American people that Sputnik represented a fundamental shift in military power and scientific achievement from the United States to the Soviet Union. Project Score was the president’s belated recognition that appearances were of primary importance in the new space age; during his last two years in the White House, Eisenhower would give as much weight to intangible factors such as world opinion and prestige as to missiles and spacecraft.