Eleven

Alias Walter Wanderwell

Walter was not the man Aloha — nor anyone else — thought he was. In April 1917, during the Great War, he had been arrested by the local Atlanta constabulary and handed over to the federal Department of Justice, who kept him detained under suspicion of being “an agent of a foreign power” — a spy. Walter was grilled by federal agents convinced they had caught him in the act of collecting crucial intelligence and transmitting it back to Germany. Walter denied spying. The attorney general for the state of Georgia, acting under the direct auspices of the president of the United States, took over the interrogation.

The interviews he conducted are illuminating and are some of the few documents that show Walter without Aloha’s colouring lens. They shed some light upon Walter’s “activities,” both real and suspected, but are still perplexing. Some even predate his first marriage to Nell and the beginning of the Wanderwell Expedition in 1919.

*

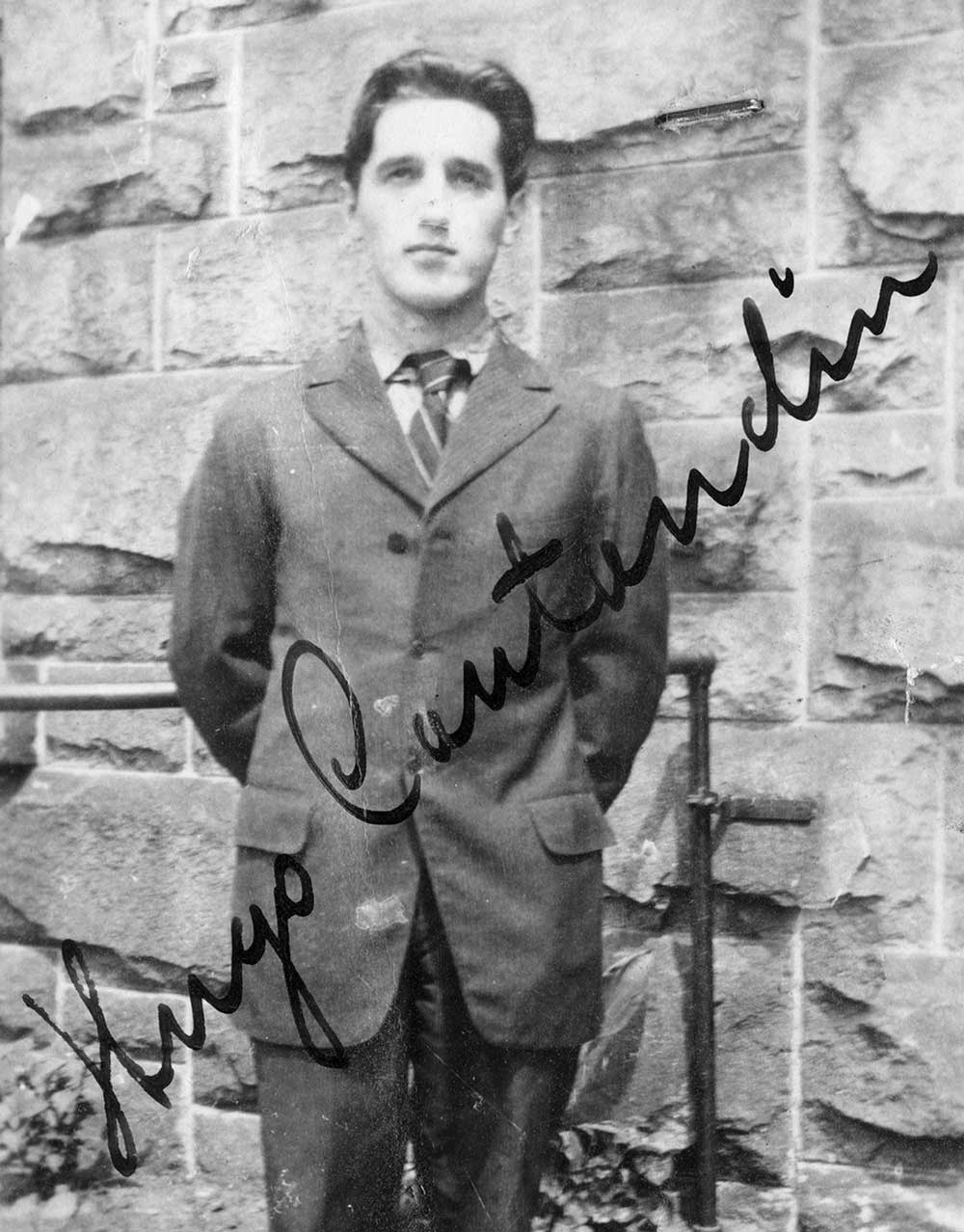

Bureau of Investigation file photo of “hiker” Hugo Coutandin, Walter’s companion, after arraignment as a possible spy and incarceration in the infamous Fulton County Tower jail, Atlanta, Georgia, 1917.

Hooper Alexander, the US district attorney for Northern Georgia, could hardly keep up with the directives flooding in from superiors. War with Germany looked likely, and its possibility was churning up the biggest panic since the Civil War. Citizens were ready to surrender their rights and liberties in order to safeguard the country’s political and social order — indeed, they were demanding it. Political trials swelled,1 and anyone with a funny-sounding accent might be reported to authorities as a potential spy. County jails and state penitentiaries overflowed with “hyphenated Americans”: German-Americans, Irish-Americans, Russian-Americans, as well as many foreign nationals. The vast majority of those arrested were in the United States legally. Many had been in the country for more than twenty years. They owned homes, ran businesses, and were active in their communities.

Two men who claimed to be on a “walking trip” across the country had been arrested in Atlanta. Their names were Hugo Coutandin and Walter Wanderwell. At least one of them, Wanderwell, had been arrested several times before,2 and he was wanted elsewhere in the US to face civil charges relating to the Mann Act. It was this charge — defined as transporting a female across state lines for immoral purposes — that ultimately gave Alexander the legal right to hold Wanderwell indefinitely. And Alexander was keen to hold on to Wanderwell. Aside from maps and photographs of strategic coastal facilities in Florida, Georgia, and the Carolinas, authorities also found among the hikers’ effects a “portable” two-way radio (telegraph) and two cameras. Unlike many recent detainees, preliminary information gained through the questioning of these two prisoners, and witnesses to their debatable activities, gave sufficient cause to suspect that they actually were engaged in some form of espionage.

On March 27, Alexander received instructions from US Attorney General Thomas W. Gregory advising that it would be “desirable to hold all parties if possible, using any local legislation, the Mann Act, or any statute which may be applicable.”3 Gregory’s Espionage Act had just failed passage in the Senate and he was in no mood to see more potential agitators slip from his grasp. President Woodrow Wilson was equally annoyed, proclaiming, “There are citizens of the United States . . . born under other flags but welcomed by our generous naturalization laws to the full freedom and opportunity of America, who have poured the poison of disloyalty into the very arteries of our national life . . . [T]he hand of our power should close over them at once.”4 Less than a month later a presidential order arrived:

April 21, 1917

United States Attorney, Atlanta Georgia,

By order of the President of the United States, acting under proclamation and regulations as to alien enemies, issued April sixth, nineteen seventeen, you are ordered to arrest and detain, through the United States Marshal, at the usual place of confinement in your District, the following German alien enemies, on the ground that their presence in your District at large is to the danger of the public peace and safety of the United States: Walter Pieczynski and Hugo Coutandin.

Such persons shall be held until further order of the President.

—Gregory5

*

Alexander, a tall man whose goatee, deep-set eyes, and prominent brow gave him an imposing look, spent his day in a small interrogation room of the Fulton County Tower, an antebellum structure used as the Atlanta city jail. Walter Wanderwell sat in front of him. As promised in the morning paper, the storms and tornadoes of recent days had given way to warm, sunny weather and made it necessary to place a small oscillating fan on the room’s desk. The buzz-hum of the fan and the clacking of a secretary’s stenotype machine filled the pauses as the fifty-nine-year-old attorney questioned his twenty-two-year-old subject in detail.

Q. Well, now, let’s talk with very great frankness to one another.

A. Thank you.

Q. You know why you are held?

A. Yes.

Q. You are a German?

A. Yes.

Q. And you understand very well that you are suspected —

A. (Interrupting) Of being a spy.

Q. Something of that sort; that you are not in this country innocently but co-operating in some way with the German Government and against the interests of this country . . . .

A. Yes.6

Walter Wanderwell, or Valerian Johannes Pieczynski, was born in Thorne, Germany, on December 5, 1895. For most of its history, Thorne had been at the heart of the Polish kingdom but had come under German control in 1793, when the city was annexed by the kingdom of Prussia as a hedge against expanding Russian influence. Wanderwell’s family was often transferred from one town to another, dragged along by his father who was a veterinary surgeon in the kaiser’s army.

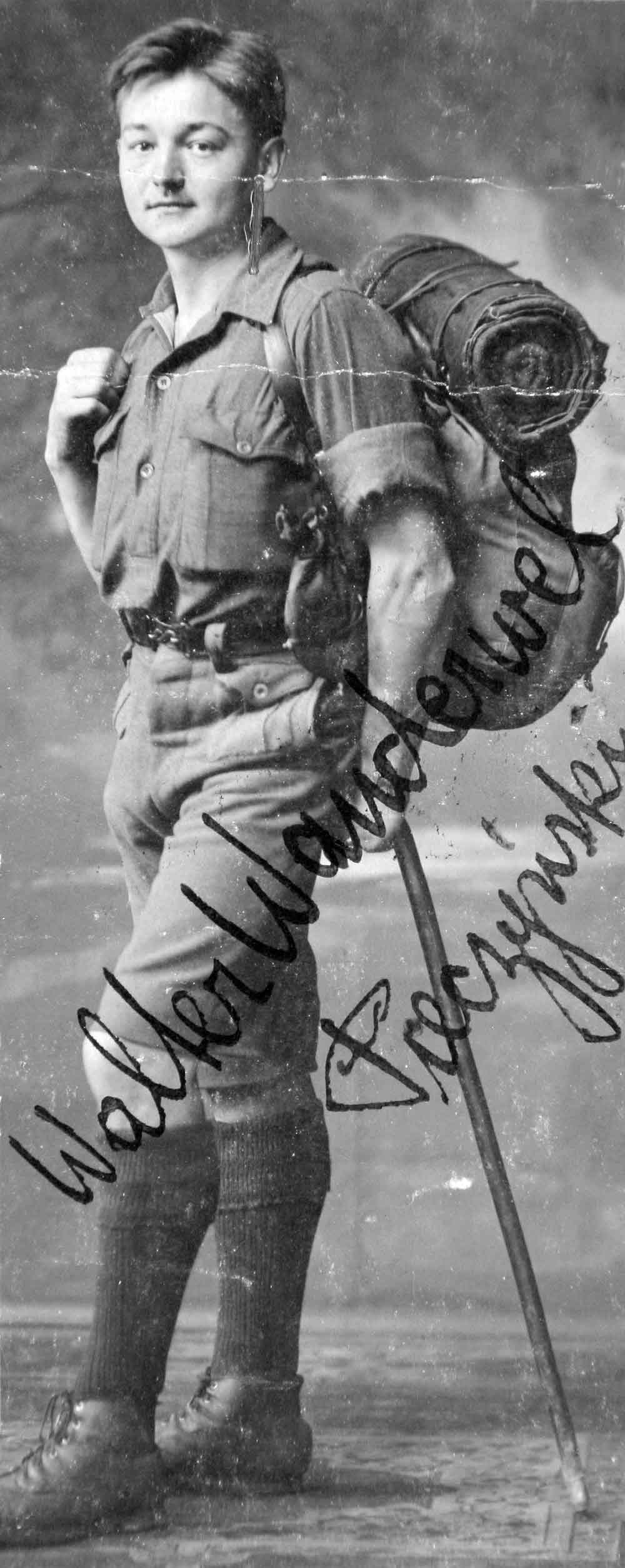

Q. In what regiment?

A. He was transferred from one regiment to another. Altogether in the German Army twenty-nine years.

Wanderwell told of growing up in Alsace-Lorraine and Posen and Schlösschen, though he could not provide exact dates. He had attended school, mostly in Posen, until he was “going on 17” and had been a member of the Wandervögel — a German pathfinder organization similar to the Boy Scouts, though placing more emphasis on harmony with nature than survival skills. Before the Great War and in the postwar years before the rise of the Nazis, thousands of young people in hiking shorts and colourful costumes could be seen hiking around the German countryside with banners flying, guitars and rucksacks slung on their backs, in search of a better way of life — exactly what Wanderwell was claiming to do when he was arrested in Atlanta in March 1917. Early photographs of Wandervögel members show them wearing uniforms that bear a striking resemblance to Wanderwell’s own uniform — and it was clear that the name “Wandervögel” was the inspiration for his own pseudonym.

A very young Valerian Johannes Pieczynski (a.k.a. Walter Wanderwell) with one of his elder brothers, Posen, Poland, circa 1890s.

A studio portrait of thirteen-year-old Valerian, Posen, Poland, 1900.

But Alexander was not interested in arcane German youth movements. He wanted to know why, at sixteen, Wanderwell had tried to enter the German army in 1911, especially since he professed to have no sympathy for the German people. Wanderwell responded with plainspoken enthusiasm.

I was made crazy by stories of Navy life. I was very adventurous . . . I desired to see other countries, to see the world; that is why I (eventually) became a sailor. They (the Navy) did not accept me because I was nearsighted.

After asking Wanderwell to repeat that he was turned down by the German army, Alexander made a sudden change of tack.

Q. Have you ever been to Cardiff?

A. Yes, Cardiff, South Wales.

Q. When?

A. I don’t know the year, but I was there on a Norwegian sailing ship. I will give you an account of my story, one after another. They didn’t accept me in the German Navy, and I was so desirous to go to sea that, when they did not take me in the Navy, I went on one of those merchant vessels, where they give the boys training.

The exchange marked the first time that Wanderwell and Alexander vied to steer the course of the conversation, as well as the first time that Alexander demonstrated he already knew quite a bit about Wanderwell’s history.

A publicity photo of a young Walter Wanderwell found amongst US military intelligence files, circa 1915.

Q. Did you go on the Norwegian ship “Cambus Kanetta”?7

A. Yes, an old English ship, and that ship was registered under the Norwegian flag. I signed on as ship’s boy.

Wanderwell described his first voyage from England, down through the South Atlantic and around Cape Horn to Antofagasta, Chile. He claimed to be in Chile on April 14, 1912, when news came that the Titanic had sunk. He would have been 16½ years old. He told Alexander that he sailed on the “Cambus Kanetta” for eleven months, including three months in Balboa, Spain, loading and unloading the ship. Given that Balboa is a hamlet of about twenty houses in the hills of northwest Spain, it seems Wanderwell was actually referring to the northern port city of Bilbao. It’s unknown if this error is Wanderwell’s or Alexander’s. Obfuscation was a habit that Walter maintained throughout the interview (and indeed through his life): long-winded explanations, bloated with superfluous detail that managed to omit essential dates and facts.

Alexander asked about Wanderwell’s four brothers, whether they were in the German army, whether his father was still alive. He asked for more details about Wanderwell’s sailing career. Wanderwell said he’d worked on routes around the globe, including trips along Africa’s Gold Coast to Lagos and the Niger River, where he travelled inland to deliver goods to the British colonies. Often there were unexpected layovers, such as two months in the Canary Islands waiting for a new ship propeller, when Wanderwell was able to do some “sightseeing” and learn a bit of the language.

While sailing to the Spanish port of Huelva, a telegram informed the crew that Austria had declared war on Serbia.

Q. When you left Huelva where did you touch next?

A. Baltimore, Maryland, United States.

Q. Do you know the date?

A. I was on the ship until ready to leave the harbour. It was twenty-five days across the Atlantic. In Baltimore, Maryland — we didn’t know anything of the war; the ship didn’t have any wireless outfit. When we reached the shores of Maryland the American pilot came aboard with the news that there was war declared between Austria, Germany and England, France and all the nations, and we didn’t believe it — thought it was a joke.

Wanderwell said he’d demanded to be paid off in Baltimore and only got his money after threatening legal action. He never did provide the date of his arrival but instead made a statement that clearly surprised his questioner.

A. We went to the German Consul in Baltimore and reported ourselves there, and did not know what to do.

Q. Reported for what?

A. Reported for service.

Q. Military duty?

A. Yes. That is our duty, to report to the German Consul, but the main reason was to get our money from the ship.

As Wanderwell told it, because he had never served in the German army and did not have a passport, he was excused from enlisting. Alexander seemed unconvinced.

Q. You landed there about the 18th of August [1915]?

A. Something about that time.

In Baltimore, Wanderwell signed on to a ship called the Sark, Norwegian again, and sailed to Alexandria, Egypt. According to Wanderwell, he got the job because he could speak “Norwegian and Russian and Polish, and especially Polish.” En route to Egypt, while passing through the Strait of Gibraltar, the ship was confronted by a British torpedo boat.

The commander hollered, “Where are you bound for? Any Germans or Austrians on board?” We were sitting on deck, on the hatch, so scared they would take us to a concentration camp, we didn’t know what they were going to do. I put everything I had, German newspapers and everything, overboard on the other side — put things in the ventilators . . . . Nobody wanted to be German then.

It turned out that none of the Germans aboard had served in the army and all were under military age, so the commander made them promise that they would not leave the ship until it returned to Baltimore.

Q. Then you went on to Alexandria?

A. Yes.

Q. Did you get off the ship in Alexandria?

A. Yes, on permission of the Captain . . . . We went there in the Red Light District to have a look . . . .

Q. Didn’t you promise the British Commander of the torpedo boat you would not land?

A. We promised not to leave the ship before we reached the United States . . . . The British authorities came aboard and asked us practically the same questions, and gave us a special pass for every man to go ashore.

Alexander seemed appalled at the nerve of the sailors to disembark in Alexandria but decided not to pursue it.

Q. Where did you go from Alexandria?

A. We had to pass many submarines, French, and from Alexandria we went clean back to the Straits of Gibraltar again.

Q. Sure?

A. Yes.

Q. Didn’t you stop at Algiers?

A. Algiers?

Q. Yes.

A. I was in Algiers with the “Germanic.”

For once Wanderwell seemed surprised by Alexander, although he quickly grasped the question’s origins.

Q. Did you ever tell anybody you were in Algiers?

A. Yes; later on I met this hiker. I never intended to make any globe-trotter of myself, but the newspapers asked me, and I told them I had been in Africa. I made these stories — didn’t make them, but generally the newspapers made more than there was to it. I have never been in Algiers after the war.

Pouncing on Wanderwell’s sudden discomfort, Alexander asked other questions concerning tall tales, harmless or otherwise.

Q. Did you ever tell anybody that when you were in Egypt and Algiers you got through by having false papers?

A. No.

Q. Never told anybody that?

A. Told Enden I signed on as a Russian.8

Q. You really didn’t have any passports?

A. No. A sailor did not need a passport at that time. At the beginning of the war the situation was not so strict. If I had wanted to spy I could have done so.

Alexander was understandably sceptical and asked Wanderwell to name the master of the Sark, which he did. Then he asked if Wanderwell had visited the German consul in Buenos Aires. He had. Then he asked again:

A. Yes, but that was before the war.

Alexander knew that German agents had been operating in Chile at precisely that time, and the United States’ response led, ultimately, to the establishment of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Wanderwell denied having been in Chile during the war.

Q. Did you ever go by land from Chile to Buenos Aires?

A. No.

Q. Ever tell anybody you did?

A. I have told all kinds of stories when I was making lectures and talks.

Q. You were just “stuffing them?”

A. I have told them much of my adventures. Another boy traveled across on land on foot. He told me much about his trip from Valparaiso to Buenos Aires. I intended to make that trip with him.

Q. What was that boy’s name?

A. I don’t know . . . .

Q. Do you know the date when you were in Buenos Aires?

A. No.

Knowing it would be possible to check the story against shipping records, Alexander focused on establishing Wanderwell’s arrival in America.

Q. Did you quit the “Sark” in New York?

A. Yes.

Q. Do you know the date?

A. No.

Q. February two years ago?

A. Yes, that is when it was. I have it on my papers . . . .

Q. Did you report to any Consul at New York?

A. No, not after that time; I had so much interest for America.

This, again, was a potentially volatile line of questioning. In 1915 German officials in New York — including the head of the office of Germany’s War Intelligence Centre — had been caught producing forged passports that allowed Germans to leave the United States for Europe. Then, in July 1915, the German commercial attaché in New York, Heinrich Albert, forgot his briefcase while stepping off a train. By the time he turned to retrieve it, a US Secret Service agent was sprinting down the 50th Street Station platform with the briefcase tucked under his arm. Inside were receipts for funds transferred to German-American and Irish-American organizations aimed at influencing American public opinion. There was also evidence that Albert had funded a munitions plant in Bridgeport, Connecticut.9 The discoveries had outraged the president and solidified American public opinion that Germany was working against the welfare of the United States. Author Chad Millman wrote about the mood at that time:

The California Board of Education banned the teaching of German in public schools because it was a language that disseminated “ideals of autocracy, brutality and hatred.” Local libraries threw out German books, and the Metropolitan Opera stopped performing German works. Restaurants renamed sauerkraut “liberty cabbage” and hamburgers “liberty sandwiches.” A Minnesota minister was tarred and feathered after he was heard praying with a dying woman in German.10

Wanderwell’s mere presence in New York during those months was enough to cast him in a suspicious light.

During the spring of 1915, Wanderwell worked on ships sailing along the Eastern Seaboard of the US, the Gulf of Mexico states, the Caribbean, and Cuba. Then in July 1915 he applied for US citizenship at New York.

Q. When you applied for citizenship you took an oath?

A. Yes.

Q. You said you would give up the German Emperor?

A. Yes.

Q. Said you would have nothing else to do with him?

A. Yes.

Q. Would not obey him?

A. No.

Q. Did you mean that?

A. Yes.

Q. You were going to become an American citizen?

A. Yes.

After more than an hour of questioning, Alexander was approaching the crux of his case against Wanderwell. Although he claimed to have nothing more to do with German authorities, Alexander could demonstrate that Wanderwell had, in fact, visited numerous German officials. In Chicago, Wanderwell had met with the consul on several occasions and was known to have discussed leaving the United States.

Q. Never made any effort to go to Vladivostok?

A. No. An attaché of the German Consul tried to help me, and wrote a letter to show to the German authorities.

Alexander’s interest in Vladivostok was more than passing. In 1915 German agents connected with German consular offices in San Francisco, Chicago, and New York had been placing bombs onto ships loaded with munitions. The ships sailed from Tacoma, Washington, to Vladivostok. That Wanderwell was linked to Vladivostok at that time must have seemed curious.

By March 1916 Wanderwell had given up sailing. His right foot had been broken in an accident at New York Harbor and in order to relieve the stiffness brought on by three months in hospital, he began hiking. He set out from New York along the newly completed Lincoln Highway, the nation’s first transcontinental road for automobiles. From New York he walked 90 miles to Philadelphia, then struck out west towards Chicago, selling postcards and lecturing at German clubs along the way. In Chicago, Wanderwell tried to see the German consul but met, instead, Carl Ludwig Duisberg, an attaché. Duisberg was not willing to give Wanderwell any money, which was sometimes the custom, but he did hand him a letter of recommendation to the German consul in San Francisco, Baron E.H. von Schack.

Q. Didn’t you tell Ludwig you had made all kinds of efforts to get back to Germany?

A. Yes.

Q. Was that the truth?

A. No.

Q. What did you tell him about going to Vladivostok?

A. That was an effort to get that letter, that recommendation. He told me I could get an opportunity to go from San Francisco to Vladivostok, but I did not want to go there. I never had an intention to go there.

Carl Ludwig Duisberg Jr. was well known to the US government and had been watched for some time. His father was the head of Bayer AG and would eventually found IG Farben.

Letters of recommendation in hand, as well as some private mail for the German officials’ friends on the west coast, Wanderwell struck west for Salt Lake City, where he arrived in the fall of 1916.

Q. Did you meet a man in Salt Lake City by the name of Lutzig?

A. Yes, that is the man that took us along in the automobile to San Francisco.

Q. Who was he?

A. He was traveling in an automobile from New Orleans. He comes from Berlin. His wife is German too . . . .

Q. I don’t think I ought to ask you anything about anything you did about that woman. That might put you in the hole, and you had better not testify against yourself.

A. I don’t know if I have done anything wrong, but I would like to tell the truth.

This, presumably, is a reference to one of Wanderwell’s Mann Act misdemeanours, and prosecution of those charges would keep him off the streets for a while. But if Wanderwell really were engaged in espionage, it would be foolish to focus on hanky-panky while ignoring his espionage efforts. There was something fishy about Wanderwell’s activities in San Francisco. Alexander asked Wanderwell if he had visited Baron von Schack, but he denied it, claiming the consul was sick.

Q. Do you know where Von Schack is now?

A. No.

Q. Did you know he had been prosecuted out there?

A. No.

Q. Did you know he is in prison?

A. No.

In February 1916 von Schack and two other German consular officials were indicted for plotting a military expedition against Canada from within the United States. But they also had planned the bombing of ships bound for Vladivostok and took part in an elaborate, multinational plot known as the Hindu–German Conspiracy, which aimed to foment a pan-Indian rebellion against the British Raj during the First World War (and thereby draw forces from Europe). The plot was part of countless conspiracies taking place at the time, including the Black Tom explosion in 1916 — the most destructive terrorist act on American soil prior to 9/11.11

Shortly past midnight on July 30, 1916, German agents snuck into a section of the New Jersey harbour called Black Tom and set fire to a row of railway cars carrying ammunition that was parked next to a barge packed with munitions bound for the war in Europe. Within half an hour, bullets inside the cars exploded, making it impossible for firefighters to approach the flames. Soon the barge itself was alight, and at 2:08 a.m., the munitions detonated, smashing a temporary crater in the harbour waters before raining down in a deadly storm of water, wood, and blazing shrapnel. The explosion flattened large swaths of Jersey City and was heard as far away as Maryland. Windows shattered throughout Manhattan, water mains burst in Times Square, and the torch on the Statue of Liberty was pulverized. When a second explosion occurred at 2:40, firemen working on fireboats dropped to their stomachs to dodge the flying bullets and aimed their hoses blindly over the sides of their boat.12

One of the German agents eventually convicted of the bombing was Polish-German Lothar Witzke, a.k.a. Pablo Waberski. It’s possible that Alexander had Witzke in mind while questioning Wanderwell — especially since Witzke had been interned in Valparaiso, Chile, but had somehow managed to escape around the time Wanderwell was also in Chile. The real bombshell, however, was that Wanderwell’s name appeared in Witzke’s notebook.

By the fall of 1916 Wanderwell was heading east again, through Arizona and New Mexico in the company of two Germans — a small man named Fritz Gluckler and another whom Wanderwell did not name. At each town they would “hunt up the German heads” to arrange speaking engagements, sell postcards, and take photographs. In El Paso, Texas, they crossed the border to Mexico, where they were arrested under suspicion of being American soldiers. The German consul intervened and they were released. American soldiers had been slipping across the Mexican border looking for Pancho Villa, who had sacked the town of Columbus, New Mexico, earlier in the year. A German arms purchaser by the name of Felix A. Sommerfeld was suspected of having helped to provoke the attack — on the assumption that if the United States started a war with Mexico, it would stay out of the war in Europe. Alexander likely did not know that Felix Sommerfeld, like Lothar Witzke and Walter Wanderwell, came from Posen, Poland.

After several visits to Juárez, Wanderwell stayed at an American military camp near El Paso. At San Antonio, Walter’s travelling companion, Gluckler, was arrested and interrogated but released the following day. The experience terrified Gluckler, although Wanderwell insisted that legal troubles were just part of the adventure, another interesting story they could add to their lectures. While his companions denounced the xenophobic Americans, Wanderwell insisted that there was nothing to fear and, as if to underscore it, tried to see the governor of Texas at Austin. He succeeded. Governor James “Pa” Ferguson signed Wanderwell’s book and said he had also travelled through the southwestern United States as a young man, drifting from place to place and learning what the country was really about. It helped him decide what he wanted to do in life.

Since leaving California, Wanderwell claimed to have earned over a thousand dollars hiking around, a staggering amount in 1916. He had robust bank accounts in Miami, New York, Chicago, and England. But, according to Aloha’s later memoir, the war also played a role in the group’s success. German communities welcomed them as minor heroes: the brave German adventurers who struck out to see the world despite its troubles. Throughout the United States, Germans felt conflicted about the war, wanting on the one hand to support their new home but also feeling that Britain, France, and Russia had been unfairly aligning against Germany for years. The press’s depiction of bloodthirsty Germans bayoneting babies for sport sent many tempers boiling over. Inevitably, some Germans were radicalized.

Wanderwell’s travelling companions grew increasingly nervous until Gluckler decided it was too dangerous to continue hiking, believing they would surely be arrested as spies.

Q. Why did he say they would arrest you as German spies?

A. We were arrested along the road, held, searched.

Q. Where?

A. In other places.

Q. What other places?

A. In El Paso. He was, for instance, held in El Paso.

In fact, Wanderwell had been arrested in at least four US cities, a detail he was careful to omit, not realizing, perhaps, that Alexander already knew. At Christmas 1916 Wanderwell reached West Palm Beach, where he befriended a German named Hugo Coutandin. Before long, the two men were hiking and lecturing together, promoting the idea that they were racing around the world on a bet. Wanderwell, perhaps to deflect American suspicions, began introducing Coutandin as a Frenchman.

Q. You say he is French?

A. French descent. His forefathers were French; like I am a Pole.

Wanderwell and Coutandin visited countless German organizations in towns throughout central and north Florida. In Gainesville they were made honorary members of the Boy Scouts of America and were keen to play up the association as much as possible, “on account of these difficulties.” Then, in St. Augustine they stopped to take some photographs.

Q. What pictures did you take there?

A. Nothing but snapshots; nothing that could have looked suspicious.

Q. What pictures did you take in Saint Augustine?

A. All kinds.

Q. Was there a wireless station in Saint Augustine?

A. Oh yes, that is right. That is the only point in the whole thing where they could get me for a German spy. We came to Saint Augustine and I had my camera along and took pictures of the old Fort, and tried to take pictures of the “Fountain of Youth.” There was a lighthouse there and . . . I went up to (it), and the man told me we could take pictures . . . . I said, “Can we take a picture of the wireless station?” He said, “They might think you are German spies.” I said, “I am English.” But that picture was spoiled, and I never got anything out of that picture.

Wanderwell’s story couldn’t have done much for his case, especially since he suddenly claimed that Fritz Gluckler, who had supposedly left the tour in West Palm Beach, was with them when they took photographs of the wireless station. What Alexander did not say was that he possessed the testimony of Mrs. C.F. Fowler of Waterloo, Iowa, who claimed to have met Wanderwell at a wireless station in Jupiter, Florida, (236 miles south of St. Augustine) at 2:00 a.m. When she asked him what he was doing there he told her he needed a match. Alexander also knew that among Countandin’s belongings was a portable two-way radio, a strange (and heavy) item for a backpacker to carry.

Q. And you think you are not a German spy?

A. I think I am not. I know you are mainly holding me because you think I am a German spy. That is why I want to tell you anything you want to know. I am not a German spy, and not afraid to stand up for it. I am only afraid because they might accuse me of breaking a law I do not know anything about . . .

Q. Didn’t you go to the West Coast to go to Vladivostok?

A. No; I said that to sympathize with the Germans. I am for the German people and say the German system is all right, but I say militarism is a thing of the past. I am only for one thing. I think there will come a time when the nations will come together to have a Peace League. The President of this country started that, and I think they will come to that agreement.

Wanderwell returned to his cell at the Fulton County Prison and Alexander took the stairs back to his office, where he sat at his desk for a long time, organizing his thoughts. Through his window he could see the dome of the Georgia State Capitol building blazing in the late afternoon sun. The US Attorney General was awaiting a report outlining Alexander’s impressions of Wanderwell and Coutandin. It was a curious case to be sure, especially since the folks in Washington weren’t telling all they knew about Wanderwell. In the grand scheme, the charges against Wanderwell were fairly minor: some letters couriered, a Mann Act violation, and some snapshots of wireless stations in Florida. And yet Alexander had received no less than ten wires directly from the US attorney general, several from the assistant attorney general, who in turn was working on information provided by Bruce Bielaski, chief of the Bureau of Investigation of the Department of Justice. One wire about Wanderwell seemed to have come from President Wilson himself. For some unstated reason, Washington wanted Wanderwell and Coutandin.

Alexander interviewed Hugo Coutandin two days later and prepared his reports for Washington, taking into account the country’s likely entry into the war in Europe. His letter to the US attorney general, dated April 12, 1917, (six days after the US entered the First World War) observed:

In the main both of them tell a fairly consistent story. As I stated, however . . . there are some conflicts between them, many of them apparently not of a serious character, and yet difficult to reconcile . . . . Wanderwell has admitted to me that many of the stories which he has told in different places are untrue, though he has offered very plausible explanations in regard to the same . . .

As I stated in my telegram and in my previous letter, I have not been able to ascertain enough about any of these parties to lay any serious foundation for a charge against them, and on the whole I am rather disposed to believe that their motives are innocent. The Special Agent of the Bureau of Investigation, however, who has collaborated with me more or less in this work seems to be very much of the opinion that these men are all seeking information for the benefit of the German government, and I cannot feel that it is entirely safe just now to turn them loose.

The best opinion I can form in the matter is that it would be better to take them out of the hands of the civil authorities and detain them for the present in a military prison of some sort and until such time as the War Department may feel it safe to discharge them.13

Wanderwell and Coutandin were removed to a military camp at Fort McPherson and by September 1917 both had been placed on supervised parole, though officials were careful to keep them apart (Coutandin successfully lobbied for “house arrest” with relatives in Chicago). Wanderwell remained on parole, working with engineers at the Battle Hill Sanitarium just outside Atlanta, until his parole was cancelled on April 13, 1919. By August 1919 Wanderwell had married Nell Miller and was preparing to drive around the world on a bet. In the grandest of ironies, the car that Walter and Nell began their adventure in had been hand-fashioned by German POWs incarcerated next door to Walter’s prison. The send-off in Atlanta was attended by hundreds, including Governor Hugh M. Dorsey of the State of Georgia.14