ONE

THERE'S NO PLACE LIKE HOME

On a bright July morning in 1912, a fifty-foot cabin cruiser named the Inlet Queen arrived at the settlement of Qualicum Beach on the east coast of Vancouver Island. Stepping out into the hot summer sun were Herbert Hall, his wife Margaret, and newborn infant daughter Miki. Watching from the newly painted deck was five-year-old daughter Idris.

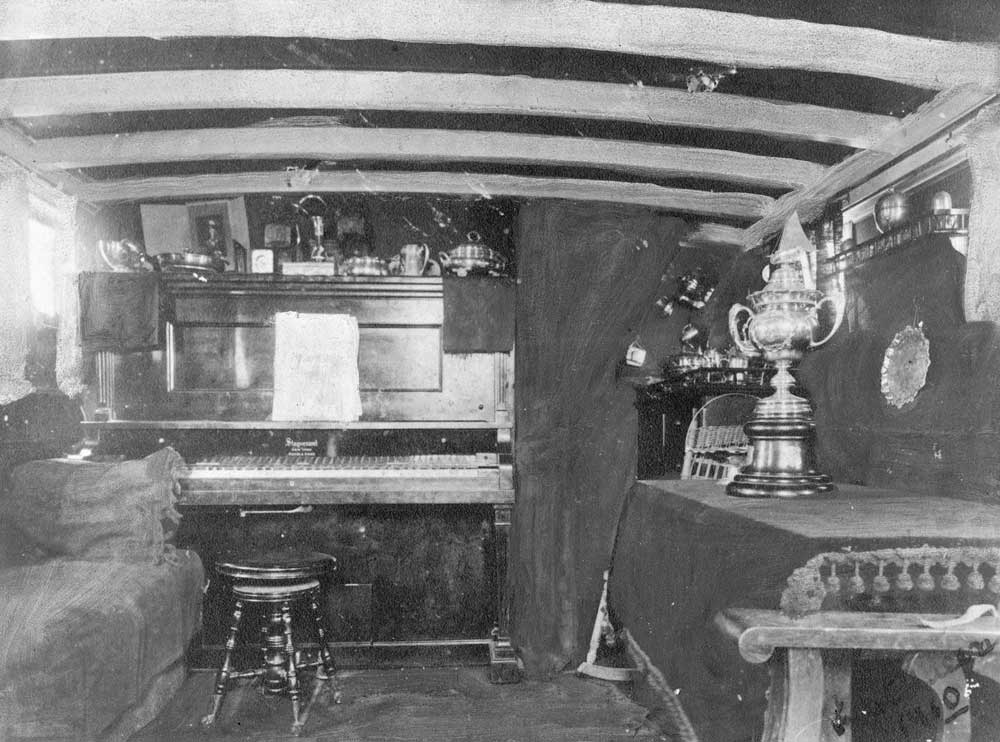

While her parents walked carefully around the small rocks and driftwood on the lip of their new property, Idris preferred to stay on the boat, combing her doll’s long blond hair. The cruiser had snug beds, a kitchen, even a living room complete with piano and gramophone. But most important of all, here they were together.

For as far back as Idris could remember, “home” was the place where she stayed put while her parents went off without her. At Grandpa Hedley’s house in North Vancouver, Idris was scolded for being too noisy, too rambunctious, and too present, while the other Hedley grandkids were doted upon, sung to, and read to. Most of her days were spent playing alone in her bedroom while the older cousins enjoyed the run of the house. By the time she was five, Idris had firmly associated the word “home” with separation.1 Travel, on the other hand, meant exciting times with the people she loved best. Travel brought treats and adventures and Daddy reading tales of Peter Rabbit. As far as Idris was concerned, they could keep on sailing forever. Why leave the lovely pleasure craft when solid ground meant staying put and the end of every good thing?

*

At the dawn of the last century, Vancouver Island was a lush rainforest paradise. Ancient fir stands stretched more than 400 feet into the air. Ravens and eagles circled the skies and kept watch over a misty, rolling landscape that plunged to a gentle sea dotted with seals and orcas. Europeans had been poking around since the 1840s, but few had actually settled. In 1900 hardly a thousand Caucasians inhabited the 5,000 square miles along the island’s east coast. But for the British, the Edwardian era of colonial expansion and opportunity was in full swing by 1905, and things were beginning to change.

Rumours of a railway from Victoria in the south to Port Hardy in the north drew settlers from around the world with the lure of newly arable land, plentiful natural resources, and the promise of well-paying jobs. Territory that had been populated by Coast Salish, Esquimalt, and other Indigenous peoples for millennia was suddenly crawling with Americans, Germans, Russians, Scandinavians, Chinese, Japanese, and most of all, English. The collapse of English agriculture in Great Britain, combined with a weak stock market and rapid urbanization, had removed the gilded sheen from the English upper classes. Landowners suddenly found themselves without tenants and, consequently, without a stable source of income. Estates that had belonged to families for centuries were being liquidated, their heirs flung out to the far corners of the British Dominion to prospect for new sources of wealth. One such Englishman was nineteen-year-old Herbert Cecil Victor Hall.

Herbert, or “Bertie,” was born June 26, 1887, at Tickhill, Yorkshire, and came from a well-known Nottinghamshire family that had once controlled vast properties. Herbert’s grandfather, Thomas Dickinson Hall, had served as the sheriff of Nottingham and Lord of the Manor of Whatton, a sizeable village. Herbert’s father had been a captain in the Boer Wars and had sent his sons to Haileybury Imperial Service College, a school once attended by Rudyard Kipling. For Herbert, however, the rigors of a service college were too constricting. Though he respected military tradition and understood the responsibilities of authority, he saw no place for such discipline in his own life. Schoolwork didn’t interest him nor did the conventional attitudes of his fellow students. He had few friends, and thanks to an injury suffered while riding on the Hertford Heath in 1903, he did not compete in any sports. Herbert dreamed of a more exciting, freewheeling sort of life. By his second year at the school, Herbert was regularly running afoul of school authorities, most seriously in the spring of 1905 when Housemaster A.A. Lea caught Herbert with “smoking materials.” By September, Herbert had left Haileybury and was at the Manor Farm Agricultural College at Garforth.2

After less than a year there, Herbert received a letter from an older brother regarding investment opportunities in Canada. Unlike England, Canada was bursting with chances to earn a fortune in farming, mining, logging, fishing, heavy industry, and especially real estate. A national railroad, the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), had been in existence for just twenty years, and by the early 1900s the trickles of westward immigration swelled to a flood. In 1906 Canada’s population was just over six million people, and of these, nearly a million had arrived in the previous ten years.3 It was, in other words, a nation waiting to be made.

Herbert quit the Manor Farm and set sail for Canada, where he would complete his education at the High River Agricultural School, just south of the city of Calgary. It was, at long last, his chance to set out on new adventures.

*

Herbert’s ship docked in Montreal in the early summer of 1906. He made his way west, by train, across the prairies. The High River School of Agriculture had been founded in 1903 by fellow Englishman Oliver Henry Hanson of Cambridge. Hanson was one of many English “agricultural experts” who came to Canada to train prospective farmers. He advertised his school as a place for young English gentleman farmers. Tuition was fifty pounds per annum and the course lasted two years. According to one source, “Hanson supplemented his income by imposing fines on his trainees for infractions such as being late for breakfast, not shaving and not having their hair combed.”4 By 1909 Herbert had left Alberta5 to settle in the town of Salmon Arm, British Columbia, a fruit and vegetable growing microclimate.

Salmon Arm was settled predominantly by English. The town boasted a country club, cricket matches, lawn bowling, and a soccer league. Herbert probably came to Salmon Arm to explore farming opportunities but instead wound up discovering an Englishwoman named Margaret Jane Hedley — tall, elegant, a few years his elder, with an exciting disregard for convention and a fondness for giant hats. She was, like much else in Herbert’s life, an unusual choice.

Unlike Bertie, however, Margaret was not to the manor born. The eldest of six children, she was raised in the coal country of northeastern England. Her father, James, had worked in the collieries, and although he had risen to the position of foreman, family life was frugal and luxuries scarce. Finding a long, tiring line of would-be suitors unappealing, Margaret made a life-altering decision. Marriage would have shackled her to the duties of a coal miner’s wife, the likes of which she had seen many of her female friends endure. Around 1901, at the age of twenty-two, Margaret found her own way out, taking a CPR steamship to Canada. Eventually settling in Winnipeg, she fell in love with a CPR employee named Robert Welch, who, ironically, hailed from a town barely 5 miles from Margaret’s birthplace. Five years later, on October 13, 1906, Margaret gave birth to a daughter. Idris Welch was born at 77 Hallet Street in the Selkirk district of Winnipeg. According to Idris’s birth certificate, her mother was Margaret Hadley and her father was Robert Edward Welsh.6 The certificate claimed that Margaret and Robert were married, but there is no record of the marriage.7 It was the beginning of a cascade of errors — sometimes accidental, sometimes wildly concocted — that would persist in official documents throughout Idris’s life. It’s unclear when the couple left Winnipeg to move west and settle in Salmon Arm, or even what finally became of Robert Welch (a piece of family correspondence between cousins suggests he fell off a ladder and broke his neck), but by 1908 Margaret Hedley was single again.8

Margaret Jane Hedley Hall, Aloha’s mother. Photo taken about the time of her marriage to H.C.V. Hall, British Columbia, 1919.

Photographs taken in Salmon Arm show a scowling, three-year-old blond girl seated on a horse-drawn wagon in the company of her mother and several adventurous-looking men with prodigious moustaches, all wearing their Sunday best. These were probably a series of wedding day portraits of Herbert and Margaret’s marriage that took place on October 16, 1909, in Herbert’s own home with local Baptist pastor H.P. Thorpe presiding.9

Baby photograph of newborn Idris Welch (Aloha), Winnipeg, Manitoba, October 1906.

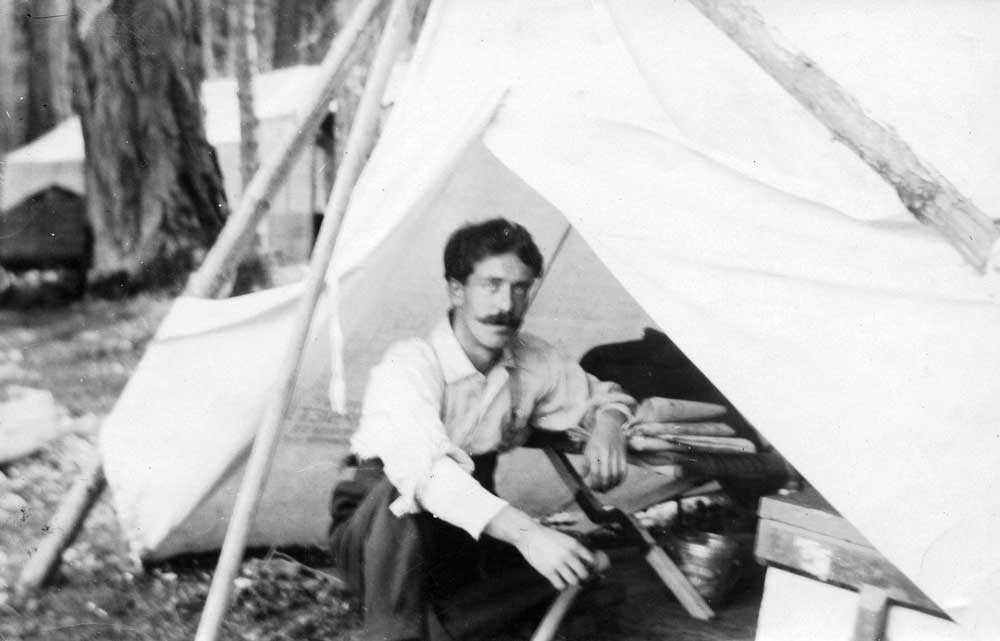

Herbert Hall in his canvas tent on the newly purchased Hall property on Qualicum Beach, Vancouver Island, British Columbia, 1914. While the plot of land was being cleared and the initial living quarters were being built, both he and Margaret stayed in the tent .

The ink had hardly dried on their marriage licence before they packed up and moved to the west coast of British Columbia. Margaret’s father had emigrated with the entire Hedley clan to the scenic slopes of North Vancouver and Margaret and Bertie decided that familiar family surroundings would benefit them all, especially a growing Idris.

North Vancouver was a thriving town of five thousand souls and had earned the nickname “the Ambitious City.” Herbert became a partner in a branch office of the Manitoba Fire Assurance Co. and was soon dabbling in real estate development, building single-family dwellings.

The decision to move west proved a good one. North Vancouver’s industries couldn’t hire fast enough and news of the good life attracted an influx of working-class families. Before long the Ambitious City became “the City of Homes.” The extended Hedley-Hall household was quite content.

However, the Halls were accustomed to being Lords of the Manor, and North Vancouver already had its established wealthy families. When rumours of a new railway line on Vancouver Island surfaced, Herbert saw his opportunity. The line from Victoria, north to Port Hardy would open vast stretches of prime real estate. New industries and settlements were bound to follow, just as they had done in Salmon Arm and North Vancouver.

With funds from the sale of their North Vancouver properties, Herbert bought heavily forested property along Vancouver Island’s east coast. Idris was left behind with her cousins and grandfather in North Vancouver, while Herbert and Margaret spent much of 1911 living in a canvas tent, clearing the most scenic part of a forty-acre promontory in Qualicum Beach. By early 1912 they had built a cabin to serve as a temporary home until the family manor could be constructed.

*

As it turned out, Qualicum Beach was the highlight of Idris’s childhood. The arrival of a little sister — baptized Margaret, but nicknamed “Miki” — provided Idris with a playmate, and in future years both sisters would treasure the memory of their time there: days spent exploring the forests or summers spent paddling “in the shallows (while) mum ‘dipped’ in her cumbersome bathing costume, sometimes even removing her stockings.”10 The sisters befriended the deer that braved human contact in exchange for crackers, apples, and on more than one occasion, their daddy’s beer. On sunny summer afternoons, Margaret would pack a picnic lunch and box up the gramophone. The trio would march down to the shingle beach, where they’d twirl their skirts and croon along to the hits of the day, especially, Idris recalled, the song “Beautiful Ohio.” One 78 rpm record contained ukulele music. Playing it would prompt Idris to begin a slow hula-style dance, wearing an imaginary grass skirt. Sometimes Margaret would play this record for dinner guests and ask Idris to “do your Aloha dance.”11

(L-R): Idris Hall, baby Miki and Herbert Hall enjoying their oceanfront property at Qualicum Beach, British Columbia, 1913.

Young Idris standing thigh-deep in the Salish Sea at the foot of the Hall family property, Qualicum Beach, British Columbia, 1913.

(L-R):Miki, their nanny, and Idris at the foot of the Hall family property on Vancouver Island, Qualicum Beach, 1914.

It wasn’t all flights of fancy and wooded kingdoms, however. Idris watched as her father applied his Haileybury and High River Agricultural School training. Forests were pulled down, timbers sawed and planed, and all that wood repurposed as buildings, fences, and signposts. Ranch land was created, the first schoolhouse erected, and a ribbon of road was laid along the coast to the huddle of shacks that served as the town centre. As his crowning achievement, Herbert worked with architects to design the Hall family manor, scheduled for completion in two years’ time. While the town around them sprouted into existence, Margaret and the kids tended the family gardens and readied the stable buildings for horses.

For Margaret, a life lived close to the land and sea was happily familiar. Although she had grown up in a mining community, she had often travelled to the North Sea coast on family outings. Striving to attain the trappings of a newly minted middle class, the Hedleys managed a few niceties, and as the eldest, Margaret benefited. While schooling was limited, as it was for most young women of the time, Margaret was able to learn equestrian skills and sailing, pursuits that made Vancouver Island — so dependent on horses and sailboats — feel like home.

For Idris, too, Qualicum Beach imprinted itself on her mind: this was, finally, home. No longer just one of the cousins, she was now part of a stable family — and one that was thriving in a vast and beautiful setting. Nothing could shake Idris from this idyllic life. Or so she hoped.

In April 1913 their boat, the Inlet Queen, sank during a promotional trip to Nitinat on Vancouver Island’s west coast. Maritime author J.A. Gibbs gives an account of what happened:

All went well till the Inlet Queen left dockside. Nasty winds were fanning the Strait of Juan de Fuca, and all the way to the Nitinat Coast the craft took a terrible pounding. The passengers became violently seasick. In crossing the Nitinat Bar, the craft ran hard aground and the passengers were forced to struggle ashore, sick, wet, and discouraged.

Despite the setback, including the total loss of the Inlet Queen, the real estate firm was persistent. They still planned a resort similar to those on the coast of southern England.12

Although the disaster did little to dissuade Herbert (after all, the Hall family motto was “persevere”), the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand in faraway Sarajevo was about to test the whole world’s perseverance.

The Hall family launch, Inlet Queen, docked at the foot of Victoria Harbour in front of the Empress Hotel. Note the square portholes. Victoria, British Columbia, 1915.

The interior lounge aboard the Hall family launch, Inlet Queen, Victoria, British Columbia, 1915.

*

England’s declaration of war on Germany caused skilled labour to vanish overnight. During the war’s first week, the Canadian militia requested that twenty thousand men sign up for service in Europe. One hundred thousand men responded. Herbert, whose military training made him a natural candidate, would have been expected to leave at once but Margaret begged him not to go. She reminded him how much he was needed in Qualicum Beach, not just by his wife and daughters but by the many families he employed. It was an excruciating decision for Herbert and he tarried through 1914, doing his best to mothball his numerous projects until the war was over, hopefully by Christmas. As 1914 passed, however, the news coming from Europe was cataclysmic. Germany had wiped out the Russians on their Eastern Front and had progressed so far into France they’d nearly captured Paris. The world was in shock, and the failure of the Allied forces to halt Germany was widely blamed on a lack of troops.

Studio photograph of Lieutenant Herbert Cecil Victor Hall, Durham Light Infantry, London, England, 1914.

Pressure to join the fight became a tidal wave that swept over Canada. War propaganda was everywhere. One famous poster asked women, “Is your ‘best boy’ wearing khaki? . . . If he does not think that you and your country are worth fighting for — do you think he is worthy of you?”13 It wasn’t long before businesses and entire towns were being run by wives and daughters, while the men signed up and were shipped to England for training and dispatch. For Herbert, raised in a military tradition and schooled at a college whose motto was, and continues to be, “Fear God, Honour the King,” the call of duty was eventually too powerful to resist.

On May 3, 1915, Herbert, now twenty-four, signed his attestation papers for the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF), committing himself to serve for as long as His Majesty King George V should see fit.14 He was commissioned as a private and placed in the 29th Battalion of the CEF, otherwise known as the Vancouver Battalion.15 He kissed his wife and daughters goodbye and just two weeks later was in Halifax where, on May 20 — amid a throng of rowdy recruits, many of whom had never fired a rifle — he boarded the SS Missanabie and sailed for England. In June the men of the Vancouver Battalion were sorted and sent for training in Romney Marsh, Kent, a flat, treeless expanse that simulated the denuded landscapes of rural Belgium, where Herbert would soon be assigned.

*

Herbert stayed with the Vancouver Battalion for less than six months before transferring to the 12th Battalion of the Durham Light Infantry (DLI), where he was tasked with overseeing the construction of new trenches and facilities and was the keeper of maps for his unit. In a few short weeks he had gone from building houses with sweet-smelling Canadian pine and cedar to piling limp sandbags in a pit and fortifying shelters with scrap timber and flattened tin cans. The British General Staff had a policy against making the trenches too liveable, based on the notion that comfort discouraged “the offensive spirit.”

In Qualicum Beach, Margaret did her best to keep up appearances. She wore her biggest hats to all the church functions, kept the horses well brushed, and made sure her girls’ dresses were neatly pressed. Inside, however, she was collapsing. As a child, her birth mother had died suddenly. Then, her first love had been killed in an accident.16 The thought of losing Herbert was more than she could stand. It certainly didn’t help that the teatime talk among the ladies from town was dominated by rumours from Europe: whole fields of infantry cut down in neat rows like wheat by German machine guns. Some women were astonished to hear the men were even fighting on Sundays and when it rained. According to one young woman, “Every boy I ever danced with is dead.”

Worse than the news from the front, however, was the lack of it. Letters from the front to Canada took as long as four months to arrive. It often happened that a cheerful missive would arrive from a soldier weeks after his family had received the telegram informing them of his death.

As the months ticked by, Margaret began to withdraw. She no longer wrote to the family in North Vancouver, especially since her brother, James, had also gone to war. She hired a nanny to watch and tutor the girls, much to Idris’s consternation. Although she didn’t understand the full scope of events, she was old enough to see that her mother was unhappy, that her beloved daddy was away, and that her comfortable life was under threat.

*

When a telegram arrived in early July 1916 saying that Herbert had been injured in France and was recuperating in England, Margaret made up her mind. The distance and the wait were simply too much. She and Miki packed their bags for England. Idris, however, would be left behind. Perhaps Margaret felt she would be safer in Canada or that she should continue her schooling or that she would be too big a handful to manage, given the situation. Whatever her reasons, Margaret made arrangements with a Victoria boarding school.17 For Idris, it was the start of yet another separation from her family, but also perhaps the first record of an error in her birthdate. Somewhere in the whorl of moving from North Vancouver to Vancouver Island, and from Qualicum Beach to Victoria, her birth year was changed from 1906 to 1908. It’s unclear whether Idris actually knew her true age — both dates crop up in documents spread across the years. This uncertainty about her birthdate would come to have serious consequences.

Herbert convalesced at the Cambridge Military Hospital in Aldershot. Miki and Margaret found Herbert in good spirits, though his right thigh had been littered with shrapnel during battle at the Somme.18 A photograph taken during an afternoon stroll around the hospital grounds shows Herbert leaning on his cane and smiling at the camera, while Margaret, in a pinstriped dress and large flowered hat, looks down at little Miki, wandering the overflow tents in her white frock. The expression on Herbert’s face is, unmistakably, fatherly pride.

Lieutenant H.C.V. Hall, daughter Miki, and Margaret, taken during Herbert’s convalescence from a wound suffered during battle, Aldershot, England, 1916.

While Europe was torn to pieces, Idris was waging her own kind of war. Unhappy to be confined in the school dormitories, she regularly escaped (usually to attend the cinema) and was placed under house arrest for pummelling a boy who called her a sinner. Later, when Herbert’s brother, Algernon, came to visit in his Ford Model T, she convinced him to teach her how to smoke. It appeared that Idris’s school career would turn out rather like Herbert’s. She was restless and she wanted to be with her family. So deep was her desire to get to England that, in later years, she claimed to have left Canada in January 1917, even describing life in a London cold-water flat with a collapsible Primus stove, the alarm of Zeppelin raids (one blast levelling Miki’s nursery garden), the clang and shriek of trains grinding into Victoria station, the sight of fresh troops departing Charing Cross, people kissing in public, and everywhere the “acrid reek of coal smoke, steam.”19 However, ship manifests plainly reveal that Idris was in Canada until after the war’s end.

*

Once Herbert was returned to the front, an uneasy routine settled upon Margaret and Miki through the spring of 1917. One of Herbert’s letters noted that the men were working non-stop, though Margaret could not have imagined how literally he meant it. The 23rd Division was part of a colossal mining operation at a place called Hill 60, near Ypres, Belgium, one of the most feared theatres on the Western Front. The project’s objective was to mine the whole of the Messines Ridge, occupied by the Germans. The rise, although hardly as high as a second-storey bedroom, was one of the few vantage points in the area, and any view of opposing trench lines was invaluable. For ten months Australian, Canadian, and British troops had rooted under the ridge and along a smaller opposing escarpment called the Caterpillar, laying mines. While the DLI 12th Battalion was not directly involved in tunnelling, they were responsible for defending the trenches and conveying explosives while the digging continued.

By early June the tunnelling was complete and the explosives in place. At 1:00 a.m. on June 7, 1917, the British moved to their jumping-off positions. At 3:05, the troops were instructed to lie flat on the ground. Five minutes later, close to a million pounds of explosives were detonated inside nineteen tunnels under the German front line. The result was a man-made earthquake that instantly killed ten thousand German soldiers. It shook the bed of British prime minister David Lloyd George at 10 Downing Street and rattled pint glasses in Dublin.20 It was the largest human-created explosion in history up to that time.

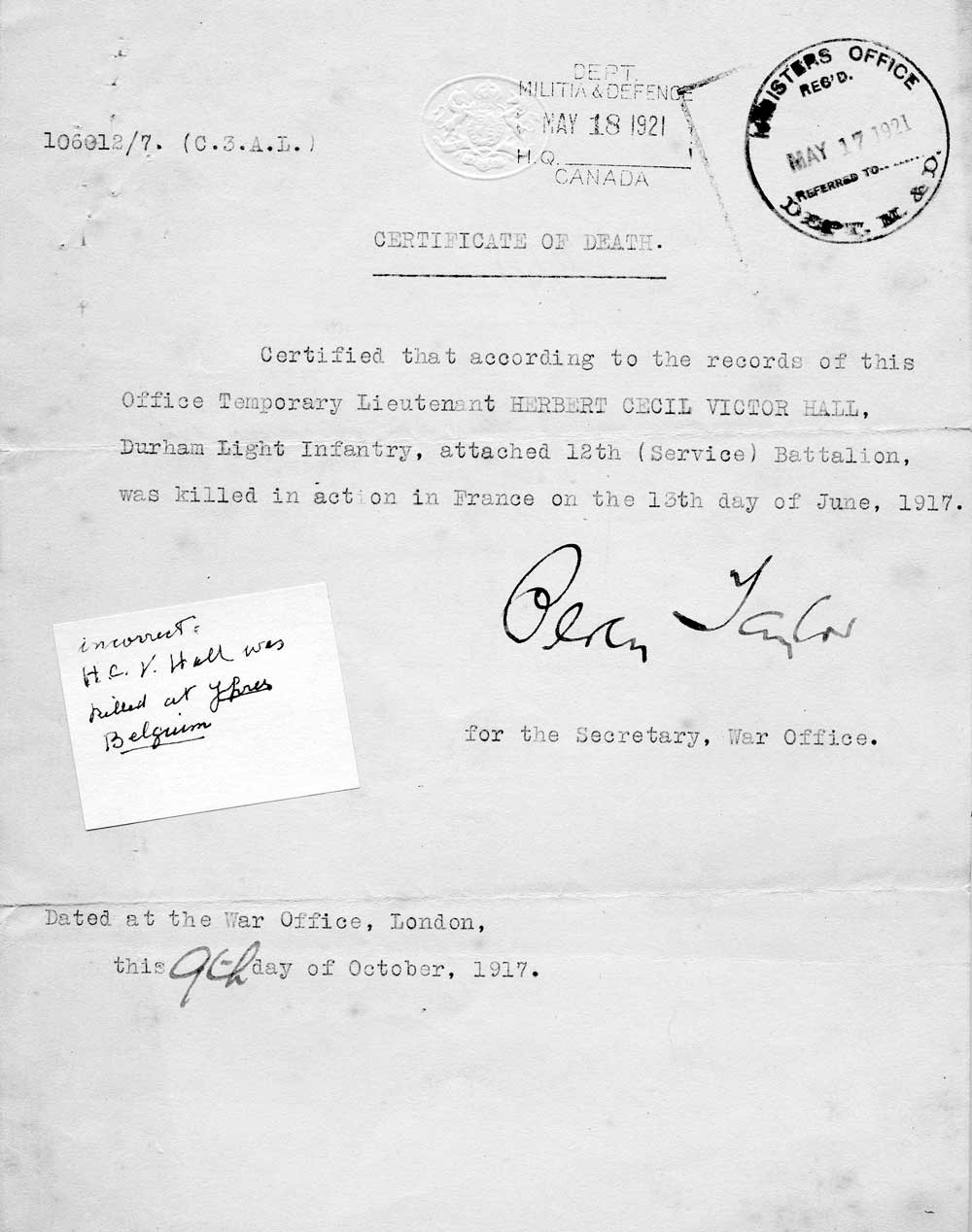

Following the blast, the left flank and most northerly unit was the 23rd Division. It was up to them to fight off what German resistance remained and secure the capture of Hill 60. On June 13, six days after the detonation of the mines, Herbert was working with two other officers on a construction detail in an area of Ypres called Battle Wood. Late in the afternoon, the 12th Battalion’s forward position came under German shelling. One explosion caused a trench wall to collapse. As soon as the dust settled, the troops scrambled over the debris towards shelter. Just as the last men were clearing out, another heavy shell fell directly into the trench, badly injuring two officers and vaporizing Second Lieutenant H.C.V. Hall. Bertie was gone. Not so much as a fingernail was recoverable. He was mentioned in dispatches “for gallant and distinguished service in the Field” and posthumously awarded a service medal.

Official British military ‘Certificate of Death’ for H.C.V. Hall dated October 9, 1917, but retrieved from Canadian archives in May 1921. Aloha’s own sticky note corrects the information, stating Herbert died in Ypres, Belgium, not France.

*

Margaret was bereft. In the weeks that followed, she tried her best to look after the family’s affairs, including the reading of her husband’s last will and testament. Documents had arrived from the family’s barrister in North Vancouver, stating that Margaret was to act as sole executrix to Herbert’s estate. According to the will, Herbert’s possessions in England were to be divided between his brothers, Henry and Algernon. This amounted to some dusty furniture, a few pictures, a gold watch, and a battered cigarette case. Herbert’s Canadian property and possessions would pass to his “beloved and faithful wife” Margaret, with the exception of the family silver, which he bequeathed to his daughter, Margaret Verner Hall, Miki. There was no mention of Idris at all.21

Idris had been too young to remember her birth father, Robert Welch. When Margaret and Herbert wed, she was barely three years old. The revelation contained in Bertie’s will forced Margaret to tell Idris the truth: Herbert had been her stepfather. Idris was numb with shock. Margaret told Idris to be strong. As the older sister, she needed to keep her chin in the air and a smile on her face. To set an example for her younger sister. Idris was by now ten years old, still not old enough to tell her mother to go to hell — that would come later.

The effect Herbert’s death had on Idris is evident in surviving photographs. Where once there had been a smiling, gregarious child, there was now a distant, hollow-eyed, vaguely angry young girl of indeterminate age.

The hand she had held on those long beach rambles turned out to be an empty glove. No wonder she had been left behind in Canada. No wonder she felt she had nowhere to belong and, once again, had no place to call home.