SIX

THE WORLD IS YOUR OYSTER

Aloha arrived in Paris with just one hundred francs in her pocket. She arranged to meet the captain at the Paris Ford Agency, where she was thankful they were “in the usual fishbowl crowd or I would surely have rushed up to him like a fool.”1 The agency had arranged a photo shoot to christen Wanderwell No III — Cap’s new creation and, as he spun it, the car that would represent the City of Light in the Wanderwell Around the World Endurance Contest, or WAWEC.2 He’d built the car himself, starting with the chassis of a 1917 Red Cross ambulance to which he added a host of new components, including a gleaming dashboard, floorboards, and headlights. Most remarkable, however, was the body. Instead of the light gauge steel used for Unit No II, he opted for aluminum. “The metal of future cars, airplanes, anything!” he crowed.3 His enthusiasm for the automotive uses of aluminum was prophetic. Major auto manufacturers would not start using aluminum components until the late twentieth century.4

Aloha was impressed. “She had sleek lines, lower sides, wider comfort, leg room. It was love at first sight.” Her enthusiasm doubled when the captain told her the car would be hers to pilot. “My very own Jolly-Boat. I quickly took an initial fling behind the wheel. She purred. . . . With muffler, her throb was smooth. [She was] built for derring-do.”5

Adding to Aloha’s excitement was the multinational crew the captain had assembled. There were two war veterans: one solidly built American named Eddie Sommers6 and a gangly German-Pole called Stefanowi Jarocki, former enemies who once “tossed grenades, fired at, cursed each other across the barbed wire. Now they united efforts in horizon chasing.” There was also a blond Dutch girl called Lijntje van Appelterre, more widely known as Mrs. Siki, wife of a French-Senegalese boxer known as Battling Siki. Siki had recently become the world’s first black light heavyweight champion, defeating Frenchman Georges Carpentier with a knockout punch.7 Convincing a celebrity wife to join the expedition was a stroke of marketing genius.

For Aloha, though, the most interesting new member was pretty seventeen-year-old Amanda Hoertig,8 “from South America, richly dark, handsome; she and I really hit it off together.”9 Amanda, who they’d nick-named “La Princesse,” had been Wanderwell’s interpreter since Bordeaux and quickly built a reputation as an artiste de hoopla, a free spirit with infectious energy and little regard for social norms. Even Cap, usually so serious, couldn’t help admiring her expansive effervescence. “Full of the joy of living,” he said, “uninhibited as a young puppy.”10

*

Aloha had only been in Paris a few days when Armstrong and Fate arrived, very dusty and thoroughly unmarried. Still, they were together, had delivered Unit No II in one piece, and were now “in Paris somewhere, preparing to build their own unit.”11

With both cars together, the captain wound up affairs in Paris and prepared to take his newly expanded show on the road.

When the captain announced the expedition was leaving for Belgium, Aloha refused to go along.

In spite of my enthusiasm about driving No III, I decided not to travel to Belgium again. . . . I really wanted to scoot off with La Princesse for a fling in Paris. She agreed — it was time for her sign off; Paree could be fun together. I knew Cap would disapprove. I told him that Mum wanted me home for a while. Then I wrote Mum that I was very busy (and) not to expect letters too soon, all’s well, tra la la . . .12

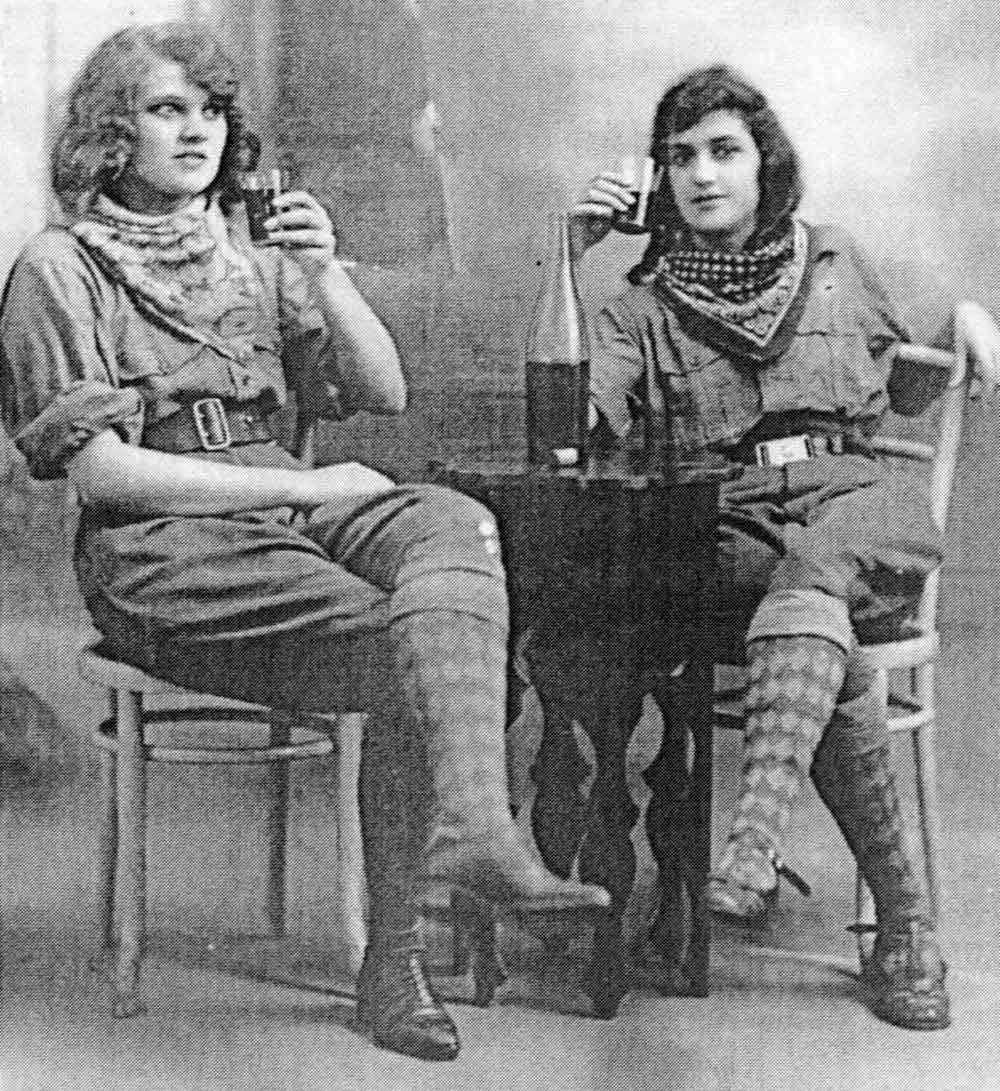

Aloha with girlfriend in Paris bistro.

On the loose in Paris, Aloha and Amanda shared a room in Montparnasse, subsisting on market food and the kindness of friends. Aloha managed to do a little modelling for the French fashion designer Molyneux, and helped a showman named Chief White Elk find engagements around the city.13 Most of Aloha’s time, however, was spent with Amanda, visiting cafés14 and markets, or arranging liaisons with various suitors.

She was a very dear buddy to me . . . a bit crazy about men, especially wealthy. Sometimes we didn’t see each other for days. . . . Seeing Paris from the rough side was much more adventurous than if lavishly chaperoned. It felt like sheer debauchery to have one’s own way entirely. . . . For posterity La Princesse and I had pictures taken a l’Apache15 seated at table with a bottle of vin rouge — explicitly going to hell-in-a-basket — Paris in the summer, at sixteen.”16

When the money ran out, a change in lifestyle ensued. La Princesse moved in with one of her lovers, to whom she’d become engaged, leaving Aloha to fend for herself. The experience was twice as expensive and half as interesting. Debauched and depleted, she was ready for the telegram that arrived from Holland. Captain wrote that the expedition was headed for Germany and he wanted her to come “at least for a few days . . . as my guest . . . can talk things over.” As Aloha put it, “I wanted to dash to him but my heart said I must go home to Mother and straighten myself out.”17

The problem was that she had no money to get to her mother, who had returned to her home in Nice. Her solution was to visit an acquaintance that Amanda had recommended. Nicknamed Old Brooklyn, La Princesse’s friend ran a successful business selling surplus war tires and was known to enjoy having the neighbourhood girls stop by for “lively chit-chat and sandwiches.” Aloha stopped in for lunch one afternoon and told him of her impending departure, adding that she needed five dollars. “Cheerfully he said ‘Ok’ and handed me out of the office . . . into a cubbyhole washroom. My God! I got the shock of my life! His pants ripped open, he was exposed in a flash!” According to her memoirs, Aloha rebuffed him with a loud no. “Red in the face, he flung open the door, shouting at the cashier, ‘Hell, give her five bucks.’ I picked up the note and walked out.”18

Aloha arrived in Nice and stayed just long enough to wash her clothes, enjoy some home-cooked meals, and otherwise recover from the exhausting improvisations of bohemian living. When she left this time, she told her mother, she would be gone for much longer.

*

In August 1923, Aloha stepped off a train in Amsterdam and was met by the captain. His “‘Old kid’ greeting of a slap on the shoulder jolted any sentimental idiotic impulses.” If she was disappointed by the platonic and joshing reunion, it was much worse when she arrived at the hotel and was met in the lobby by the new Dutch interpreter. “Petite, baby-faced Joannie van der Ray was very attractive in uniform.”19 Aloha gave her a crushing handshake and watched the reaction. “Her glance to Cap was for reassurance. I read a lot into that glance.”20 Cap had not mentioned the new and strikingly attractive crew member, nor that they were to be roomies.

The captain had secured visas for Germany at The Hague. Surviving passport documents set the date at October 11, 1923, expiring November 20, 1923.21 Perhaps more than any other destination in Europe, Germany attracted Wanderwell. Although Polish, he’d spent most of his school years in Alsace-Lorraine and Solschen, near Hannover. His German was as good as his Polish and better, by far, than his English.

In 1923 conditions in Germany were appalling. The war reparations required by the Treaty of Versailles led to hyperinflation and meant the average German was so impoverished that bread became an unattainable luxury. Rumours of starvation were widespread. Still, there was hope for change. A new and moderate chancellor, Gustav Stresemann, had come to power; he aimed to strengthen German democracy, repair relations with France, and free Germany from the heavy burden of the reparations. Now, Walter thought, might be the perfect time to promote his idea of an international police.

The expedition crossed the border at the town of Malden. Here, Belgian border guards escorted them through the dangerous buffer zone to the Rhine bridge crossing at Wesel, Germany. While the crew sat in the cramped darkness, listening to rain drum on the car’s canvas roof, Wanderwell entered the sentry building and spoke to the German guards. He drew attention to the “three pips” on his uniform and demanded they escort the cars to their commanding officer. To further assert his “rank,” the captain instructed the junior officer to carry his briefcase.

At the designated building Cap retrieved his satchel, and ordered the guard to wait outside. We watched anxiously but could see no movement in the pale light of the upstairs windows. Several minutes passed before Cap appeared, relayed his briefcase and stepped into the car. The guard assumed this imperious officer had obtained permission to cross.22

Cap used the same strategy at the town of Wesel and again at the customs house where the cars were finally allowed to enter Germany.

Impressive though he undoubtedly was, Wanderwell’s ability to overawe guards by the sheer force of his personality is a touch far-fetched. A better explanation for the expedition’s successful entry into Germany may have lain in the contents of the briefcase he was carrying. Years earlier, in the United States, Wanderwell had performed numerous questionable tasks for the German government that had attracted the attention of the US Bureau of Investigation. Walter’s relationship with the German government may have opened doors closed to anyone else.

The expedition made a beeline for the north central part of the country, hoping that if their “ruse was discovered we could be sent to the nearest exit — Poland. We had been twenty-four hours in wet clothes, no sleep, only one hot meal. We took turns at the wheel, except van der Ray.”23

The sights that greeted them as they rumbled north were depressing. In each town were long lines for food, bedraggled elderly, children in rags, and people subsisting on a barter system. The sights brought out old bitterness among the multinational crew; memories of the war died hard. Wanderwell stepped in.

Cap absolutely forbade making critical comments about the political situation. . . . [He] wanted us to learn to understand people — just as each of us had a war scar to outgrow, so also the 1914 Germans. “Individually, these are fine beings. Show them restraint and healing. Learn in a country; don’t spend your brains criticizing. . . . These Germans are hungry for friendly gestures from the outside world. They’ll whole-heartedly admire the sporting aspect, you’ll see.”24

What the captain didn’t realize, however, was that Aloha was more worried about the Dutch than the Germans.

I was very keyed up about the whole situation — the Expedition’s and my own. I felt sure our demure member of the voluptuous lips and come-hither eyes was just lying in wait to compound an untenable situation. On the job Cap treated us all without distinction — male, female. I simply had to outlast her.

It didn’t help that Aloha’s seventeenth birthday had come and gone with nary a notice.

In Hannover, shows were booked at the Dekla theatre, the city’s “number one show house.” Wanderwell handled the lecturing, managing to mix his dramatic travelogues with plugs for world peace and half-serious acknowledgements of local achievements. “If we get lost in the jungle, at least we’ll find Hannover’s worldwide Leibniz Biscuits,” he joked, shrewdly highlighting a German product that was universally loved. That mention alone earned them “a hundred pounds of biscuits, hardtack, gingerbread,” gifts that were “more valuable than their weight in paper marks.”25 Audiences at the Wanderwell shows were soon covered in crumbs as the Leibnitz company began distributing free samples, a move that further enhanced public goodwill. Local papers offered enthusiastic write-ups, praising their courage and willingness to travel without financial backing.

Inevitably, it wasn’t long before they attracted cement-faced, green-suited Polizei, because someone figured out that the cars had entered Germany without paying duty. After one evening’s show, Wanderwell was detained and the rest of the crew confined to the hotel. When he returned, Wanderwell gleefully announced that although the cars had been confiscated pending trial, they were permitted to continue their theatre appearances.

On the day of the trial, the crew gathered at the local courthouse. The captain entered his defence plea, describing the peaceful aims of the Around the World Expedition and their goodwill towards the German people. The judge was unmoved. He reiterated that the crew had “committed a grave offense, smuggling two automobiles across the frontier” and, closing his notebook, announced that they would be assessed a penalty “prescribed by our prewar statutes.” After much rustling of papers and mumbled discussions with his clerks, the judge read out a fine of 35,000 marks. The captain began to protest but was swiftly silenced.

The judge regarded Cap. “I wish you to understand, sir, I want you to remember this experience. The war has left our [country] bankrupt, unable to adjust even our laws to inflation. You are fined according to prewar values. You will pay only thirty-five cents . . . . Young man, reach into your pocket and hand me in American money, the value of five of your souvenir brochures.”26

Autographed photo of Aloha in front of Unit No IV, Europe, mid-1920s.

*

Cookies in tow, the expedition headed east to Berlin, the capital of the Weimar Republic and possibly the most culturally kaleidoscopic city in all of Europe at that time: Dada, Bauhaus, Jungian psychology, Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, Marlene Dietrich’s The Blue Angel, physics (Einstein was working at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute), Brecht and Weill’s The Threepenny Opera — all happened in Berlin in the 1920s. This creative ferment, however, took place against a backdrop of serious political and social upheaval. Liberal, modernizing forces were colliding with right-wing militants who remained outraged at the outcome of the Great War. The result was an existential uncertainty, or what one writer so vividly called a “voluptuous panic.”27 By the time the Wanderwell Expedition arrived in late October 1923, their cars crawling like “two tiny ants” beneath the imposing Brandenburg Gate, Germans were taking full advantage of the freedoms granted by the country’s new constitution.

However, both the constitution and its promised freedoms would shatter within a month of their arrival. While Aloha and Walter were preparing for performances in Berlin, on November 8 about 360 miles south in Munich, a charismatic leader and some followers stormed a political meeting and announced they had taken over the government. The unsuccessful Beer Hall Putsch, as it came to be known, resulted in more than thirty dead and injured and the imprisonment (and later trial) of its chief agitator, Adolph Hitler. The attempted coup made front-page headlines all over the world, disrupted an already fractious German economy,28 and helped put an end to a promising coalition government. As if to underscore her emphatic disinterest in all things political, Aloha’s journal entry from November 23 contains no hint of this volatile and historic event.

*

As in Hannover, the newspapers were generous. Lavish publicity led to the expedition’s biggest engagement yet: Berlin’s colossal Scala variety theatre, the largest in all Europe. According to Aloha, their shows played alongside the feature attraction, Lil Dagover in Seine Frau, die Unbekannte (His Wife, the Unknown) and nearly filled the theatre’s four thousand seats. As usual, the audience cheered and hissed according to their political biases, but the captain had devised a special speech to close the show.

As the curtain descended, cheers and good-natured guffaws nearly drowned out Cap’s voice. Abruptly a brilliant glare of spotlights flooded the super stage to reveal three almost dwarf khaki figures: Cap center, from either wing a young man marching toward him. Expectant silence gripped the audience.

In resonant voice, Cap, “Friends permit me to introduce Private Jarocki, a better man never fought for the Fatherland . . . and American Private Sommers who rallied to his flag at the age of fifteen. Once enemies, today staunch friends in a common cause . . . PEACE and (he usually had to yell it) GOODWILL!

It brought down the house!29

Not all Germans, however, welcomed the foreign visitors. Both cars were vandalized, flags stolen, masts broke and threats made against the crew, but during such a volatile time, they could not have been greatly surprised.

When it came time to negotiate payment, Walter refused cash — trying to convert it later would have been laughable. By the end of November 1923, 1.00 US dollar bought 4.2 trillion marks, a number that, as one author put it, destroys the possibility of any rational economic calculation.30 Instead, the expedition accepted goods in exchange for services.

*

With their popularity soaring, Walter found a local agent and booked the largest vaudeville house in Warsaw, their next destination. The crossing into Poland in late November 1923 was filled with pomp and ceremony. According the expedition’s logbook, the Polish embassy in Berlin had alerted border officials to the expedition’s arrival and had arranged for the presence of a contingent of Polish cavalry. Captain Wanderwell Pieczynski and Stefanowi Jarocki, the two Poles of the expedition, saluted the troops and removed the German flags from the hood of the car, replacing them with the Polish White Eagle standard.

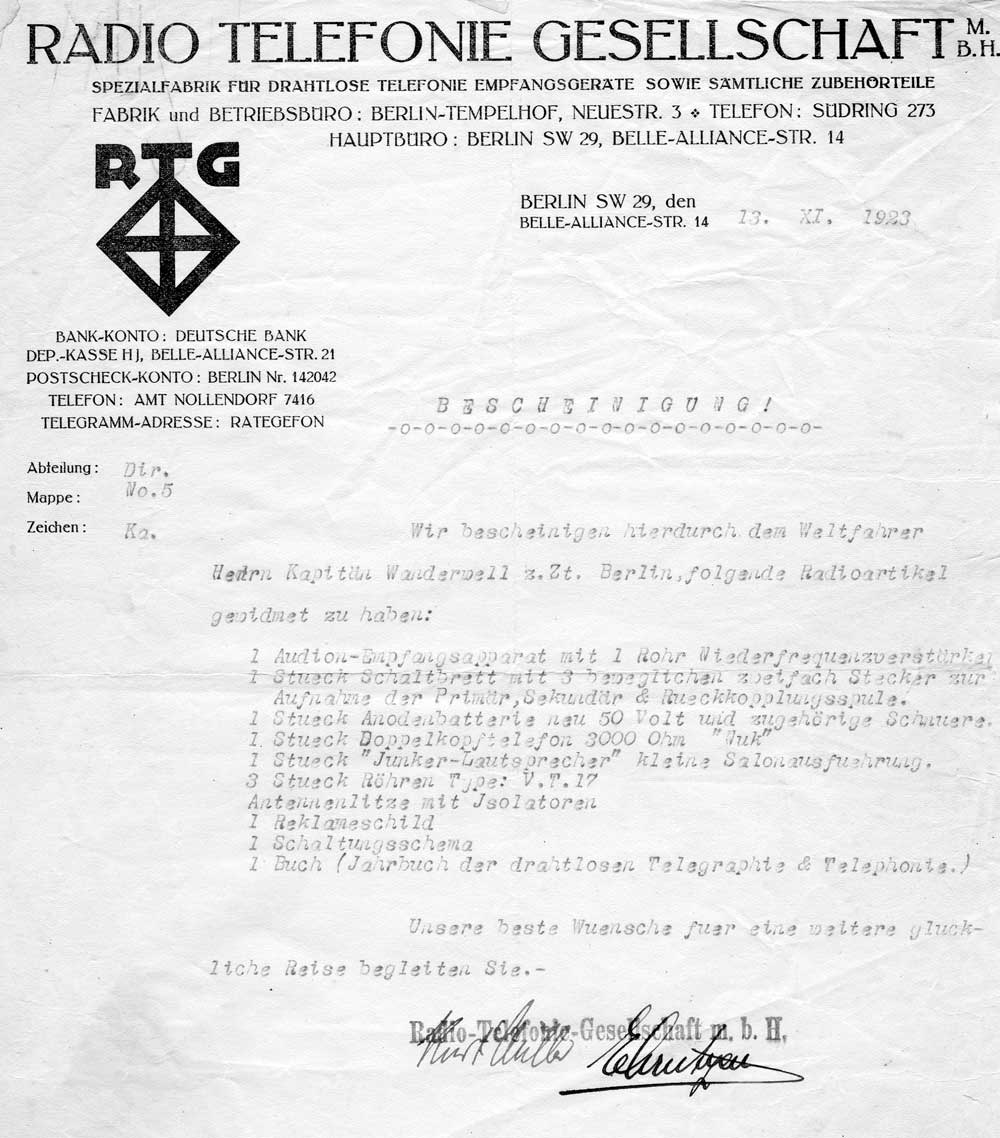

The original receipt for the “wireless” radio system Walter had installed in No II and bartered for in Berlin, Germany, November 13, 1923.

Aloha was thrilled to be racing through new territory, although the approximate 300 miles of road east to Warsaw were rough and the weather increasingly poor, fading from sun, to freezing rain and eventually snow.

We went bounding across the plains of Poland . . . through endless tiny mud-spattered villages [with] . . . small heavily-thatched roofs . . . whitewashed dwellings . . . wooden shuttered windows. Beside each [house] a well, its quaint protruding tall arm to raise and lower the bucket.31

To Aloha’s delight, Wanderwell had sent van der Ray to travel with Aloha in No III. “Cap and Sommers were in the lead, Van der Ray since being relegated to No III, no longer even a map reader. She was obviously unhappy.”32 Cap, on the other hand, was ecstatic. This was his first visit to Poland since his mother had died in 1917. In his absence, Poland had won its independence — the first time the Polish people were not a subjected spoil of war since 1795.

Partly frozen roads helped the expedition’s speed and they arrived, splattered and smeared, at Warsaw, shortly past noon. As Aloha tells it, they were met by a long line of ancient cars that formed a parade to guide them into town. The cavalcade drove through the suburbs of Warsaw, horns and sirens blaring, throngs of people shouting and waving, until they reached the military barracks at Saska Square, where they were escorted by “crack mounted officers . . . sabres and all.” When the caravan finally came to a halt they were “swamped by cameramen and reporters” and a band began playing Jeszcze Polska nie zginęła (“Poland is not lost as long as we live”).33

It was a lavish reception, arranged by Wanderwell’s two brothers, both members of the Polish military. Photographs show the captain with various dignitaries, including one taken at the headquarters of the Polish Automobile Club. Here, more than seventy immaculately dressed people crowded into one shot with the captain.

The expedition’s time in Warsaw was one long celebration. They played shows at the Cirque Warsawski, literally a ringed circus in which the cars drove around a sawdust track, intentionally backfiring, and the captain told tales of his voyages around the world. One newspaper, the Express Poranny, described Wanderwell as a champion driver, “world famous sportsman-Polack, the modern Marco Polo.”34

All was not sweetness and light, however. In between the celebrating and performing, Aloha and Van der Ray were warring. Aloha still struggled with her feelings for the captain and she was intensely jealous of van der Ray’s obviously physical relationship with him, referring to her as “The Vamp” and “Her Ladyship.” Wanderwell noticed the hostility and tried various tactics to promote harmony, initially ordering that the two always travel together, then revising to ensure they always travelled apart. Nothing seemed to work.

Van der Ray inevitably began to acknowledge that we were spoiling for a good fight. In spite of my determination to avoid open warfare, it seemed just a matter of time before some trivia would explode my despicable temper.35

A Christmas reunion with Walter, his brothers, cousins, and old friends. Walter is second from R, seated front row, Poland, December 1923.

By December 10, the expedition was in Kraków, where they prepared the cars for the difficult passage through the snowbound Carpathian Mountains to Romania. Tires were fitted for chains and blankets were fashioned for the radiators to prevent freezing. The crew purchased winter gear, including thick sheepskin jackets. Neither Unit No II nor No III had windows on the sides, only a canvas that could be tied down over the roof, offering minimal protection against wind, rain, and snow.

When the tour set off again, Wanderwell was splitting his time between the two cars and his two female crew members, much to Aloha’s distress. During the drive to Lwów (modern-day Lviv, Ukraine), she tried to work up the courage to express her feelings directly, but fell short.

I wished for the time when I could freely say, “This is not working, she or I must go,” but he was complimenting my snow driving, the expanded smile blasting me with his pugnacious vitality. I was numbed.36

*

Mid-December was an ambitious time to attempt a crossing into Romania. The expedition had only been on the road from Lwów a short time before snows became heavy. Despite the blanket covers, No III’s radiator froze. When No II stopped to assist, her engine stalled and refused to start again. “Nothing in the engines moved and the cars rapidly became white mounds in the vast white landscape.”37

Hardly six months after nearly dying of thirst and heat in a Spanish mountain range, Aloha found herself in danger of freezing to death in the foothills of the Carpathian Mountains. But luckily, a rural policeman discovered the stranded travellers and fetched military horsemen. The horses dragged the cars back to Lwów.

There was much guffawing among the riders poking fun at the poor cars, suggesting Cap hire mules to pull him around the world. Their officer kept pace beside me, joking and teasing in German. Presently he suggested Jarocki take No III’s wheel and I ride astride with him. We trotted off through the mists of flying snow.38

In town, the expedition was given beds at the local barracks. Wanderwell insisted the crew turn in early as he planned to make another attempt the following day. Aloha, however, had been invited to the opera by the rescuing officer, whom she identified as Lieutenant Walek Towarczyk of the Sixth Tank Corps. Sneaking out of the barracks like a schoolgirl, she was taken to visit the officer’s sister — who loaned her a gown — and then out for a thrilling evening of entertainment and drink. “What a night! Don’t know which I enjoyed more — the great performance or the excruciating excitement of outwitting Cap.”39

At the end of the evening, back in her Wanderwell uniform, Aloha was escorted to the barracks by Walek, only to find “Cap sitting against my door, fast asleep. It was so humiliating to have one’s self-esteem lowered in this way.” It was past four in the morning but Wanderwell was instantly awake, furious. In the tone of an outraged parent, he reviewed her offences.

Everything from his promise to mother to protect me, to the dangers of strange army officers and the evils of cafés chantants consumed most of his argument. Then he began . . . all his favourites: “Every man comes into this life with a shovel, some to dig a pit ever deeper seeing less and less, others to build a mound and climb to the heights of vision.” I was really getting the works! . . . “On this Expedition the work comes first!”

I was so offended I was unable to answer.40

In his anger, Wanderwell overlooked the real reason for her flamboyant insubordination: Joannie van der Ray. Aloha wanted to make Walter jealous by cavorting with a real officer, to see if her absence would provoke worry. Instead she saw only anger. And to make matters worse, it was probably van der Ray who had reported her absence.

Without pausing to write a farewell note, Aloha left the barracks and made her way to the train station where she used her expedition earnings to purchase a ticket to Vienna, and onward to Nice. More than adventure or even money, Aloha wanted to be appreciated — something that Walter Wanderwell, it seemed, would never offer her. Writing of the event decades later, one can still sense the intense emotion that fuelled her decision.

I just couldn’t brave the outfit any longer. I had to get home. “Love can wait” were the words I found. Hope that trollop finds the game not worth the coin. If you’re going to be a girl like that, at least one should be totally circumspect — however, gloating is one of its spices, no doubt.41