TWENTY-FIVE

ALIAS ALOHA WANDERWELL

It had been ten years since Idris Hall first met the dashing Walter Wanderwell, and she had happily traded her homebound life for the promise of fame and adventure at his side. But now her reel was empty again and the people who flashed across the screen were ghosts. In some ways, the decade had brought no changes at all: she was still free to drink and smoke (which she did), and she still had only the vaguest idea about what to do with her life. Her plans for the future had died with Walter.

With Guy’s acquittal, the Wanderwell name fell from the headlines. Theatre engagements dried up, Wanderwell units worldwide disbanded, and most of the automobiles that had once heralded the arrival of the “Great Expedition” were being sold for scrap. The crew of the Carma likewise dispersed. With the boat leased, there was no seafaring means for an expedition to travel. WAWEC and the International Police had ceased generating income, and what little cash Aloha had (mostly what had been on Walter’s person at the time of his murder) wouldn’t last long.

She had two cars, a trunkful of films, some camera equipment, and a bit of land in Miami. And two children. Aloha once again relinquished guardianship of Valri and Nile, placing each into separate foster homes. Aloha claimed it was to keep the children safe, but she had always been willing to leave them in other people’s care. Valri would later talk of being placed in an orphanage for a year and records show that she was placed under the guardianship of a couple named Keown, who would later lease the Carma.

Before Aloha could make plans for the future, a magnitude 6.4 earthquake shook Long Beach on March 10, killing 120 people and causing widespread damage. The scale of carnage did not match the Miami hurricane of 1926, but the city was brought to a standstill. Emergency crews arrived to distribute food and water in the town’s main park, while those left homeless were placed in hotels and churches and billeted in private homes. The few remaining theatre engagements Aloha had scheduled were cancelled and there was no prospect of new work. In spite of this catastrophic event, Aloha could count herself lucky; the home in which she was staying on Westbourne Avenue was undamaged and the Carma had not sunk.

*

By early April 1933 Aloha was in Los Angeles, signing a Declaration of Intention to become a United States citizen.1 As with so many of Aloha’s official documents, the declaration contains numerous bizarre inaccuracies, including claims that she had emigrated from Havana, Cuba, that she was twenty-five years old, that her “lawful entry for permanent residence” was at New York, New York, and that her son’s name was “Walter Wawec Nile.” Regardless, Aloha was permitted to stay in the country.

The Carma that had been leased to the circus operator arrived in Mexico only to be prevented from landing at Mazatlán by customs officials who insisted the ship pay a large deposit on the carnival equipment. The ship’s captain, Branson, was unable to pay the duties. The crew remained stranded for several weeks until, faced with starvation and a lack of drinking water, the government allowed members to land and accepted the carnival equipment as security for import duties, lighterage, and taxes. The next day, Captain Branson and the Carma disappeared from port, leaving the crew — including Miki and Eric Owen — to forage for food and accept the charity of the locals.2

With only her cars to rely on and her money dwindling fast, Aloha decided that the only path open to her was the one with well-worn grooves. “I steeled myself to examine sheafs [sic] of letters from persons anxious to help me start a new expedition. I picked out three people and we started.”3 One particularly interesting letter came from Captain D. de Waray of Colombia’s Legión Extranjera, or foreign legion. Unaware that Captain Wanderwell was no longer alive, Captain de Waray offered the organization’s services as “International Police Secret Service agents or Intelligence Officers.” The group comprised more than two hundred military-trained mercenaries, including British, French, German, Austrian, and American officers. Although the letter did not say exactly what kind of work they proposed to do, de Waray closed his offer “trusting that we may be able to work together for mutual benefit.”4 Two hundred well-armed mercenaries offering their services to an organization whose main goal was to disarm the world was nothing short of jaw-dropping. Aloha filed the letter away as a curious keepsake.

*

While Aloha sought a new beginning, Curly Guy fought with US immigration authorities and tried to cash in on his new-found fame. After posting a $3,000 bail bond (arranged by DeLarm), he was offered a role in a movie but the deal collapsed when authorities reminded the producers that Guy was not eligible for employment as he was not an American citizen. He also tried boxing, at which “he looked very capable — or at least he didn’t fall down every time he let one fly.”5 At his deportation hearing Guy claimed that he was, in fact, an American citizen, despite a birth certificate saying he been born in Wales. But Guy said his father had been born in San Francisco, thus qualifying him for citizenship. Conveniently, all San Francisco birth records from that era had been destroyed in the earthquake of 1906. To further bolster his case, Guy called on the testimony of Eddie DeLarm — but this time Eddie refused. Outraged, Guy threatened DeLarm, warning that he would “bump him off.”6 DeLarm begged the sheriff to appoint a bodyguard until Guy could be questioned. But just two days later the men had settled their differences, and Guy arrived in court to give testimony on behalf of DeLarm who was seeking damages from a former business partner. Incredibly, DeLarm was also in court facing a charge of possessing 16 gallons of illegal liquors — and not for the first time, it seems. DeLarm’s name had “figured in several sensational airplane liquor traffic affairs.”7 None of this had come to light during the Wanderwell trial.

Eventually, Guy was deported. Immigration officials allowed him to choose any destination he wanted, provided it was not contiguous to the United States. Either Guy misunderstood the terms, or he deliberately chose to play for more time. He picked Mexico. Bizarrely, the authorities agreed. However, while immigration agents were escorting Guy to the border, he gave them the slip during a routine bathroom break at a service station. He simply disappeared.8

Over the years, Guy would re-enter the United States many times, always under an assumed name, and frequently “doing business” with Eddie. In late 1936 police in Los Angeles were summoned to a disused warehouse by an anonymous caller claiming there were loud noises coming from inside. With weapons drawn, two officers found DeLarm and Guy hiding behind a false wall. They were both detained, and later Guy was once more deported.

In the summer of 1940, he and Eddie climbed an ornate stairway to the second floor of the Hotel Roosevelt in downtown Los Angeles and knocked on a door painted with the words “Canadian Aviation Bureau.” Soon both were flying new Hudson bombers to a small makeshift airstrip in North Dakota on the Manitoba border. On the Canadian side a wheat field had been ploughed under to form an identical landing strip. When the planes landed in North Dakota they taxied to the end of the runway and turned off their engines. A team of horses was hitched to the nose gear and the planes were dragged across the border into Manitoba, where they were refuelled and flown to Scotland.9 In 1940 the United States was officially neutral and had not yet joined the European war effort. While an international agreement stipulated that warplanes could not be flown beyond American air space, nothing was said about horses dragging them through a field.10

As part of the so-called “Ferry Command,” Guy and DeLarm flew dozens of aircraft across the Atlantic. DeLarm flew until September 11, 1941, resigning shortly after crash landing in a field near Sainte-Cécile-de-Masham, 25 miles north of Ottawa. Guy, however, continued his airborne activities, and shady past notwithstanding, he was enlisted to fly a top secret mission, ferrying Canadian Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King and Major General Georges Vanier (future governor general of Canada) to England for war meetings with Winston Churchill.11

Guy’s swashbuckling, adventurous life came to an end on another routine ferry flight to Scotland. On October 16, 1941, Guy radioed that his plane had been hit by enemy fire. According to one report, his last words were, “Ditching, tanks all empty, cheerio.”12 Eddie DeLarm, on the other hand, lived a long and healthy life, surviving many more adventures (and occupying many more column inches of newsprint) before dying of cancer at his home in Tucson, Arizona, on December 19, 1975.

*

Guy and DeLarm were, at the very least, opportunists who may have had more than a passing association with one or more American government agencies. At most, they were swindlers, hoodlums, and racketeers, but they were hardly alone. Almost everyone connected with the Wanderwell trial seems to have oozed corruption. District attorney Buron Fitts, who had forced Guy’s prosecution (only to later declare that he never thought he was really guilty), was indicted for bribery and perjury in 1934 after accepting payments from a real-estate promoter, purportedly in exchange for dropping a statutory rape charge.13 Fitts was also implicated in a sex ring the press dubbed “Love Mart” that offered virgin, underage girls to wealthy clients — mostly movie moguls. It was rumoured that Fitts was being paid a “retainer” by Louis B. Mayer of MGM, among others, so that many a Tinseltown star’s “indiscretion” never saw the light of day. Money followed influence and, in Fitts’ case, vice versa. The deaths of popular film director William Desmond Taylor, actress Thelma Todd, and director Paul Bern (Jean Harlow’s husband) are just three of the many mysteries that occurred during Fitts’s tenure that were never adequately nor officially explained.

On March 29, 1973, two men paid a half-hour visit to the now retired Fitts at his home. As they left, Fitts followed them to his driveway, got into his car and killed himself with a single shot to the head. Rather than assist the dying Fitts, the two men drove away. Some reports claimed the gun Fitts used was the same weapon used in the unsolved murder of William Desmond Taylor.14

Even the man who had originally fetched Aloha from her home in Hollywood, Detective Lieutenant Ralph C. Miller, did not escape unscathed. Within months of Walter’s murder, Miller was given a desk job and then fired from the force. The reasons for his dismissal were never made public, but according to news reports, an internal police investigation had linked Miller to a prostitution and smuggling ring involving several law enforcement officers.15

*

Aloha had been back on the road for only two months when word came that the Carma had been sold to a Mexican coffee magnate and renamed the Neutal. During a test run of the ship in early October, she struck a reef near Mazatlán and sank in shallow water. After a notorious run of twenty years, during which the vessel had been a rum runner, bankrupted several owners, and had seen the death of at least two people, the schooner was no more. Aloha immediately called her lawyer in Los Angeles and instructed him to reapply for guardianship of Valri. As one reporter observed, “The petition, if granted, would give the mother charge of the daughter’s estate of $1,100, representing money received from the sale of the schooner.”16

According to Valri, it took several weeks to locate her, since her temporary guardians had sent her to yet another foster home where her name was changed. With guardianship granted, and newly flush, Aloha continued her lecture tour across the United States, travelling in Unit No IV, the supercar Walter had purchased just before the National Air Races of 1930. Valri was placed into yet another foster home.

A short time later, while tanking up at a gas station outside Laramie, Wyoming, Aloha met a strikingly handsome youth named, of all things, Walter. He was fascinated by the car and its pilot, while she in turn was more than a little beguiled by his well-proportioned frame, thick wavy hair, strong jaw, and perfect smile. She invited him to attend her show that evening in town. The next day Aloha received a handwritten note:

Oct. 26, 1933

Dear Miss Wanderwell,

Since having met and talked with you, I have decided that life is too short to live in the same place all one’s life.

If I remember correctly, you said that you were planning on getting someone to travel with you. I would like to apply for that position, or do you think that I could fulfill the requirements? Saturday will probably be my last day on this job, so before making other plans, I would like to hear from you.

Hell, all one’s life is a trial, so you cannot blame me for trying. Can you?

Sincerely yours,

Walter Baker

By December 1933 Aloha, Walter Baker, and a crew of three young women had made their way to New Orleans, where they planned to lecture and sell pamphlets over the Christmas holidays. In an interview published on December 18, Aloha said that in a life like hers, a sense of humour was indispensable.

You can get along without a tropical hat or a pair of shoes . . . but you just can’t do without a sense of humor. When you’re drenched to the skin through four days of rainstorms, when you’re cold and hungry and weak from exhaustion, you’ve got to look at your experiences from the humorous side — else you won’t last . . . [A person must look for] all the good he or she can get out of every 24 hours.17

It was vintage Aloha, and as if taking her own advice, a newspaper notice appeared several days later.

Romance fluttered behind theater wings in New Orleans Thursday when it became known that Aloha Wanderwell, prominent figure in one of America’s thrilling unsolved murder mysteries, had eloped to Gretna and had married Walter Baker, a member of the troupe.18

The marriage was intended to remain secret, but the Wanderwell car had been spotted outside the residence of Judge G. Trauth. Curious reporters began snooping and eventually found the wedding licence, which stated that Idris Hall, twenty-five years old, widow of Walter Wanderwell, had married Walter Baker, twenty-one, of Wyoming (Aloha was in fact twenty-seven, and Walter was barely eighteen). Just one year and twenty-one days after the murder aboard the Carma, Aloha was married again. When asked about Walter’s murder, she refused to elaborate.

The murder is still as it always has been to me — an unsolved mystery.

“I had thought I would never marry again. But now, with the new world trip before us, everything seems so bright, and Walter and I are so happy.”19

The marriage was sudden. Not even Miki and Margaret knew of it. When Miki (who had made her way home from Mexico thanks to some of Aloha’s Mexican friends) read the news in a local newspaper, she sent a hilarious letter to her sister, telling her, “You should really have sent our maternal parent a wire like you did last time. She’s sort of old fashioned in a way and likes those little proprieties kept up.”20 At the letter’s close, Miki advised her sister to “be smart and get this one well insured, lambkin.” Walter No II was good insurance for Aloha in any event: with an American husband, she was free to stay in the United States permanently.

As for Miki, despite numerous trips via planes, trains, and ships (after her Wanderwell experiences she refused to travel by car), she would call Canada home for the rest of her life. Following a short stint in Victoria, where she worked as an artist’s model, she returned to Vancouver Island’s eastern coast and to land she received courtesy of her father’s veterans’ land grant.

Miki Hall sits on the deck of her summer encampment on the east coast of Vancouver Island, in Merville, British Columbia, 1958. She called this place “Happy Shack.” Windsong would be built just to the north of this spot in 1962.

Her property line ended at an easement leased by the Esquimalt & Nanaimo Railway (E&N) — land that was originally planned for the coastal railroad. Since it was waterfront and very desirable, people were allowed to squat on the land, so long as they maintained it. From the mid-1940s until the early 1960s Miki spent her springs and summers here — practically on the rocky beach itself — living first in a canvas tent erected on a wooden platform and then in a shed she called “Happy Shack.” The rest of the year she travelled or spent time with Margaret at her new home in Jamaica, where she moved in the mid-1930s. During the Second World War Miki joined the Royal Canadian Air Force, deciphering intercepted Japanese codes. Sometime during the war, she attracted the romantic attentions of a superior officer and the affair lasted throughout the war. Not long after the war, the officer admitted he was already married and would be returning to his wife, somewhere out east. Miki remained unmarried for the rest of her life.

The name and year of completion of Miki’s beloved Windsong home, hand-carved into the end of the hearth, April 2008.

Miki’s Windsong cabin on Vancouver Island. The hearth piece with the Hall family motto carved into it was once the mantelpiece in Margaret’s home on the Hall property in Qualicum Beach, Vancouver Island, British Columbia, 1962.

By 1961 the E&N had been completed further inland and had no more development plans for its coastal lease. The British Columbia government and the E&N decided to sell off the land and end squatting rights. Squatters like Miki, however, had the right to keep their land (and purchase more) if they could afford to build a permanent structure on the property. Thanks to her inheritance, Miki did have the money and she purchased several lots, eventually owning 78 acres, some with Aloha. Here she built a home that survives to this day. She christened it “Windsong” when it was completed in October 1962. Nestled against the seashore and backed by a high wall of thick forest, Windsong was a paradise where Miki could watch the ocean tides and befriend the local deer, with whom she shared her home-brewed beer.

Miki remained at Windsong until the last two years of her life, when illness forced her to move to town. She passed away in her Comox condominium on May 23, 1995, and her ashes were spread at sea, opposite her beloved Windsong. The new owners of Windsong added a two-bedroom structure, maintaining the look and feel of Miki’s original design, and they still call it Margaret’s Place — after the Wanderwell era, Miki had begun using her full name, Margaret.

Mother Margaret eventually left Jamaica (donating the property to the local Salvation Army, much to the family’s consternation) and returned for a time to Canada, where she sold off the remaining Qualicum Beach holdings. She came to an arrangement with an entrepreneurial educator named Ivan Knight, who was building the Qualicum Beach Boys School on the family’s former property: in exchange for selling the land, her grandson Nile would receive free education (plus room and board) at the school. Sadly, once the properties were sold, the patriarch of the family, Herbert Hall, was largely forgotten — so much so that local records contain no explanation of why a main street running through Qualicum Beach (and terminating at the former school property) is called Hall Road. Margaret Hall lived to be eighty-three, dying at Newport Beach, California, on November 20, 1961.

*

True to her word, Aloha continued travelling, lecturing, and film-making — working under the name Aloha Wanderwell and usually described as Miss Wanderwell. Her South America movie Aloha Wanderwell and the River of Death played in only a few theatres and earned very little money, but she persevered. She and Walter Baker toured throughout the United States during 1934 and, by the end of the year, had purchased an aircraft for a proposed flight around the world in 1935. In one of a series of articles she wrote for the Hearst newspaper chain, Aloha announced that she was in New York planning a “Wanderwell World Peace Flight.” It was a dramatic reassertion of her former husband’s ideas. “There is always tomorrow, with new adventures beyond the horizon, new friendships to make and perhaps new mysteries to encounter . . . Captain Wanderwell is gone but his way of life and his guiding hand stay with me.”21

But the flight never happened. By October she, Walter Baker, and Eric Owen were in China, giving lectures, catching crocodiles, posing for news photos, and attending hotel-sponsored soirées. In January 1936 they reached Indochina by car. One particularly memorable image depicts an arrestingly attractive Aloha in Siam (now Thailand), standing in front of her Ford Phaeton and cradling a clouded leopard kitten. Of all the photos ever taken of Aloha, this one may best sum up her professional persona: beautiful, fearless, and potentially dangerous.

Aloha holds a young clouded leopard in Siam (now Thailand), 1934.

In Sydney, Australia, Aloha struck lucrative advertising deals with Texaco, Ford, and Nivea and made dozens of appearances in theatres around the city and throughout the continent. In November 1936 Aloha and her new Walter reached Wellington, New Zealand, before proceeding to Auckland and, one month later, the Philippines. Somewhere along the way, Aloha had begun filing radio reports to be aired in the United States and in Britain via the BBC.

A story filed in February 1937 came from Calcutta, India, and Lahore, Pakistan. Two months later she was in Ceylon and two months after that back in Port Said and Egypt, where she revisited the pyramids at Giza. The travelling continued through Europe, England, and Scotland until December 1937, when after more than two years of travel, Aloha and Walter settled in Cincinnati. When not working on radio programs for the radio station WLW,22 Aloha spent much of 1938 writing books, one “In the Lap of the Gods,”23 featuring text by Aloha and photographs by Walter Baker, and another entitled Call to Adventure! Her radio stories eventually attracted the attention of NBC, with whom she created a radio series called “Adventures in Paradise” dramatizing (and fictionalizing) several of Aloha’s exploits.24

Aloha should have been famous, and yet, somehow, it eluded her. In the wake of Walter’s death, she relied on her ability to persevere. She stuck to what she knew and pursued it with relentless determination. But while she was a quick study and had an almost superhuman ability to endure, she did not possess the genius for self-promotion and reinvention that her late husband had demonstrated. With the notable exception of her work in radio, Aloha did not reinvent herself or her expeditions. Even her approach to filmmaking remained much as it had been in the 1920s — self-focused travelogues that offered some remarkable scenery but no sound.25 As late as the 1950s, when Aloha produced My Hawaii, she still had not embraced sound recording, believing, perhaps, that live presentations could do without. Instead, Her approach guaranteed that only a limited number of people would ever hear her remarkable stories. Theatrical distribution dried up, and while a handful of her travelogue contemporaries made the transition to television, Aloha never did. It was a fatal choice, condemning her to irrelevance and even casting her as a pathetic figure, unable to adapt.

*

Aloha’s book Call to Adventure! was published on November 22, 1939, by Robert M. McBride Publishers of New York, who decided to aim the title at young adult women. Much of Aloha’s text had been rewritten by a ghostwriter who, in the style of the day, heightened the drama while subduing the trials and tribulations. Aloha was appalled and would never again trust someone else to tell her story. The book received tepid reviews and soon went out of print. Aloha agreed to purchase the remainders from her publisher. Fatefully, Aloha was not home when the delivery of the books was made, so the boxes were left at the edge of her property. A short while later, city garbage trucks arrived and carted away the apparently discarded packages. The books were incinerated.26

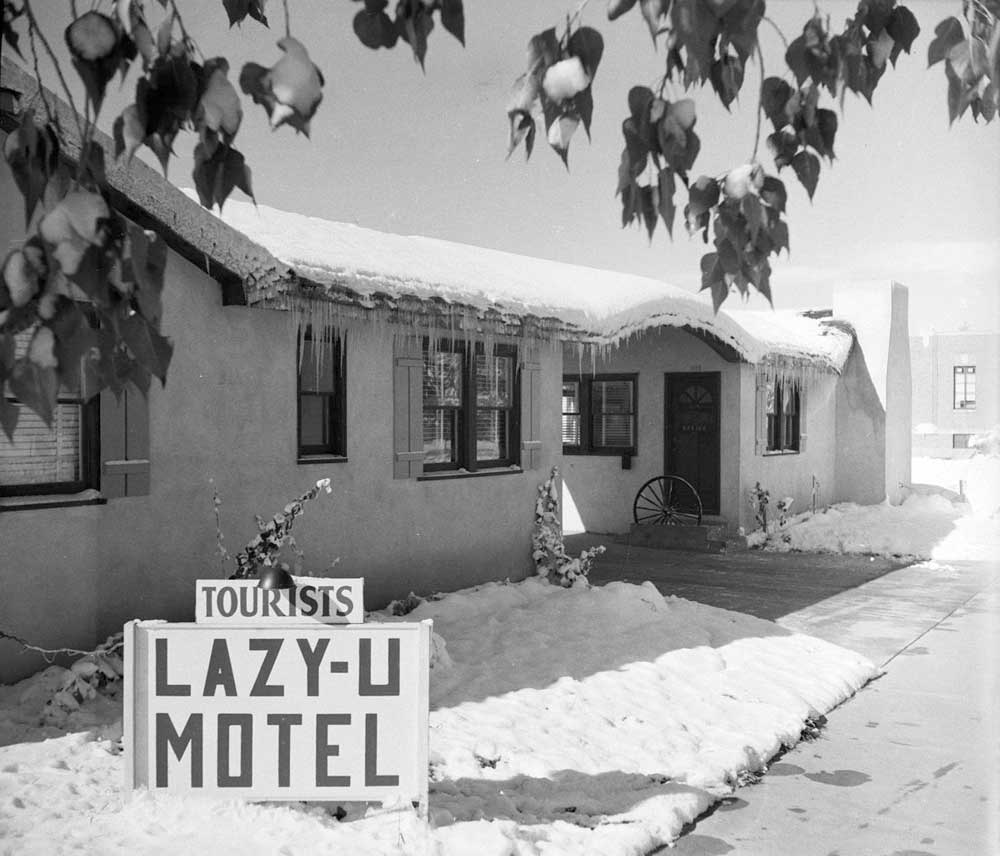

Aloha with Nile and Valri in front of their Lazy-U Motel, Laramie, Wyoming, 1943. Valri was by this time attending the University of Wyoming just across the road.

After Aloha married Walter Baker, they “retired” to Laramie, Wyoming, where they built Lazy-U, one of the first post–Second World War motor hotels in the West, 1946.

As the Second World War crept across Europe, Aloha’s ability to travel was curtailed. Her radio show ended, and except for the occasional engagement speaking at ladies’ groups, she made almost no public appearances. Realizing that the occupation of a wandering filmmaker was ill-suited to times of war, she and Walter moved to his boyhood home of Laramie, Wyoming, where they built the region’s first motor hotel, calling it the Lazy-U Motel. One of the motel’s more famous guests arrived in the 1950s. As well as teaching literature at Cornell University, Vladimir Nabokov was also an avid butterfly collector. The southeast corner of Wyoming is home to many different varieties of butterflies, and it attracted Nabokov and his wife Vera to the area — they lodged at the Lazy-U. When he wasn’t chasing butterflies, he continued his work on a book about a precocious, twelve-year-old girl named Lolita.

In 1941 Walter Baker legally adopted Valri and Nile, and they came to live at the Lazy-U in Laramie. Since 1934 Valri and Nile had been living with Margaret in Qualicum Beach, and then Victoria. For the first time in her life Aloha came to know her children and was surprised to discover that she enjoyed their company. Nile, now taller than both Aloha and Walter, demonstrated a keen creative streak, a stupendously sharp intellect, and an equally sharp temper. Valri, far more easygoing than her brother, had blossomed into beauty. A film taken in the early 1940s, when Valri was about sixteen, shows her swimming lengths in a large pool at a nearby friend’s ranch. This film needed no sound. While onlookers watch Valri swim, Aloha sits beneath a giant sun hat with an expression that looks very much like pride — and she was, after so much separation, fiercely proud of her children.

Valri attended the University of Wyoming in Laramie until 1945, when she transferred to the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque. Two years later she met and married her first husband, Louis Ruffin Jr. Valri would marry once more before meeting her third husband while modelling in Mexico. A Kodak executive named Melvin Lundahl, he would become the father of her three children: Margaret (also known as Miki), Leinani, and Jonathan. Valri was even more beautiful than her mother and, in her younger days, was a stage dancer, TV game show assistant, Mexican soap opera actress, and successful model appearing in countless magazines, including Vogue, and most famously as Pan Am Airlines Hawaii Clipper girl. Her blond hair and radiant smile continue to shine from vintage posters around the world.

Nile attended school in Wyoming and, during the war, was a member of the US Navy Seabees (or CBs, Construction Battalions) in the South Pacific. After the war, Nile settled in San Francisco, where he changed his name (to Jeffrey Baker27) and became an artist and art dealer, eventually specializing in studies of classical paintings. Nile never married but had one son, Richard.

*

By the 1950s Aloha had retired from the lecture circuit altogether. After Explorers of the Purple Sage, a film showcasing the cowboy life on Wyoming’s rugged expanses, Aloha would make only one more film, this one called My Hawaii. It was perhaps the best-crafted film she would ever produce. One particularly affecting scene shows Aloha standing with a bouquet of flowers at the rim of the Kīlauea volcano. With a sorrowful expression, she looks down at the flowers before allowing them to slip from her hands into the crater.

When the kids had gone, Aloha and Walter moved back to California, settling in Newport Beach where Walter became a developer specializing in adobe houses, including the one he built for Aloha. It was a grand two-level house on a quiet corner and had a large bay window in the upper-level living room facing west. Aloha often sat in a large cozy chair with her cat Sinbad, looking out at the boats in the harbour, the magnificent sunsets, and occasionally Santa Catalina Island would peek through the haze.

They earned a good income and spent most of their free time socializing with friends or attending horse races. Walter Baker was said to be exceptionally lucky and routinely attended races carrying rolls of cash exceeding $1,000. In later years, when the grandkids came to visit he would hand them each $100 and tell them to bet on whichever horse they wanted. Valri’s daughter, Miki, would recall winning $500 at the age of twelve, all of which he insisted she keep.28

*

As the years drifted by, Aloha began to feel that the best days of her life had been spent adventuring with Walter Wanderwell. She worried that their stories, photographs, films, and mementoes would soon be lost forever. For years she queried the Ford Motor Company, asking what had become of her beloved Unit No II, the car that had taken her so far around the world. Finally, in 1979, a letter came from the curator of the Henry Ford Museum. He wrote:

After a considerable amount of research by our registrar, we learned that this car was included in a group of old vehicles that Henry Ford decided in 1942 were of marginal historical importance. These vehicles were transferred to the Highland Park plant and eventually scrapped (for their metal content as part of the war effort). In subsequent years, many of us associated with the Museum have had occasion to express disappointment and dismay that such a decision was made, but it is a fact that we must accept obviously. We hope this information is of some help to you.29

After so many miles and so many years, the car that had carried their dreams of peace was melted down in the service of war. It was Aloha’s last link to the cars in which she had circled the globe. By 1970 not a single Wanderwell car was known to exist.30

For the next twenty years, Aloha continued to organize and annotate her collected materials, promoting them to film and historical archives, with limited success.31 Increasingly lonely, she wrote letters to contacts around the world, asking for translations of articles or follow-ups on what had happened to people she’d met along the way. At one point, overwhelmed and frustrated, she disposed of 200,000 feet of film. Then in 1989 a television producer from New York asked if she would agree to appear on camera to talk about her meeting with the famous American flyers who had been the first to circle the globe by air. Aloha said that not only would she be happy to appear, she could provide footage of their meeting in Calcutta. Producers were dumbfounded. Months later, at the age of eighty-three, Aloha made her first and only television appearance on the PBS series American Experience in an episode called “The Great Air Race of 1924.” Her appearance stirred some interest among documentary filmmakers, yet no projects came together. Some of her films were, however, placed with the Academy Film Archive and the Library of Congress.

Aloha and Walter Baker in the house that Walter built for them on Lido Isle in Newport Beach. Their cat, twelve-year-old Sinbad, sits at their feet, California, 1952.

By the early 1990s Aloha’s energy was beginning to wane, and following the death of her beloved sister Miki in May 1993, she seemed, finally, to have given up. Two years later, after more than sixty years of marriage, Walter Baker died too. Just then, however, word came from the National Automotive History Collection in Detroit that they were willing to accept her Wanderwell memorabilia (including almost five hundred photos and negatives) and would issue a tax receipt for $7,500 in return.32 Aloha rallied, writing an introduction to accompany the collection that was not so much a review of her intrepid career as it was a remembrance and tribute to Walter Wanderwell.

With clear affection and nostalgia, Aloha described the captain as “a man of originally Polish roots” but ultimately a citizen “of the universe.”

Gradually, the reader will discover the far, far deeper obsession and involvement of this truly extraordinary, charismatic man — imbued with his overwhelming esprit de corps, motivated by towering respect for the care and protection of body and soul, ever reflected in song, written word, film (the extension of spirit) and human contacts, who dedicated his life’s mind, effort, energy to the protection and expansion of universal intercommunication via technology . . . and by spirituality. . . .

One small but inciteful [sic] portion of the legacy of a very young man, very well named “Captain Walter Wanderwell.”33

Six months later, on June 3, 1996, just a few months shy of her ninetieth birthday, Aloha died of heart failure at Newport Beach. According to her wishes, she was not buried in the cemetery next to Walter Baker. Instead, she was cremated and her ashes scattered near Walter Wanderwell’s final resting place in the waters near Santa Catalina Island.

*

Aloha Wanderwell’s ability to rewrite her own history, exploit government bureaucracy, and confound her critics didn’t end with her passing. In what was perhaps a final grace note, her official California death certificate lists her date of birth once again as 1908 instead of 1906. And the Social Security number neatly typed into the corresponding document box belongs not to her, but to an African-American man named Carl Frazier, also deceased.