TWENTY-THREE

At first Aloha thought the pounding came from somewhere in the house. But as her mind swam clear of dreaming, she understood it was the door. She looked across the room at Miki, who was sitting up too. Aloha grabbed her robe, slipped it on, and rushed into the hallway. The landlady was already at the landing, fumbling to unlock the door. As it swung open, Aloha could see a man who said something she couldn’t hear, but it was clear he was looking for her. The landlady turned to gape at Aloha. Across the street, lights popped on in the upper bedrooms.

*

Aloha would recall only a pastiche of impressions: the catastrophe implied by detective Lieutenant Miller’s manner, jamming into a car with as many as six plainclothes policemen, the wail of the siren as they crossed the intersection of Santa Monica and Western Avenue, the impression that paperboys were already on the streets yelling “Extra!” (when in fact no one in the press corps had yet heard of the murder), and especially the nauseating fear that left her unable to speak.

At the Long Beach police headquarters Aloha was taken to the office of the evening chief of police, where she was asked to take a seat. The chief closed the door. There was a pause as he considered how to proceed. Aloha asked for an explanation. Had the boat sunk? Was there a fire? Had someone been kidnapped? Finally, the officer said, “I am just a simple man and I can only put this to you in a simple way. Your husband, Captain Wanderwell, has been shot.”1 For a moment Aloha’s mind did not register the officer’s words. Walter was injured or missing or had almost been shot. But seeing the expression on the officer’s face, she understood.

When I gathered my wits, the second thought was for the children. He assured me they had been removed immediately from the yacht by the juvenile authorities and that I would see them there as soon as possible but first we would together and surrounded by both the Long Beach and Los Angeles officials return to the yacht.2

While she waited, the chief asked who she thought had killed her husband. But she had no idea. In tears, she explained that Walter had many friends and, naturally, a few enemies. He was headstrong and decisive and not everyone liked his manner. Members of his own crew, she revealed, had recently argued with him about the Carma’s seaworthiness. One member, Elsa Wills, had even threatened to organize a competing expedition to Mexico, on a boat that would sail. But these were professional disagreements, not blood feuds. She could think of no one on board the Carma who would have wanted to see Wanderwell dead.

The man sighed. He closed his notebook and asked Aloha to follow him. They travelled down a long hallway, past a throng of newspaper men, and turned into a small room. Inside was a table with a tray and what looked like strips of gauze. Aloha was asked to sit down. A man in a white coat and latex gloves told her to rest her hands over the metal tray. He explained that, simply as a formality, they needed to perform a paraffin test. Aloha did as asked but was not really listening as the investigator talked about nitrates and making a wax mold, the kinds of chemicals they would add, or the little blue flecks that might arise. What she did understand was that nitrates, if present, would suggest gunpowder.

After the test, they returned to the main office where Aloha was surprised to see the entire Carma crew now crowded into the precinct. At least two girls were in tears, while others looked at Aloha with a hand over their mouths. She was not permitted to speak to any of the crew but would be taken directly to the Carma.

Just as they were about to leave, Detective Miller appeared again. He sat down on the corner of a nearby desk and began telling her the story Cuthbert Wills had told, about a man at the porthole. In an instant, Aloha believed that she knew who Wills was describing. The man’s last name was Guy, she said. He was a British adventurer and former expedition member who had tried to rough up the captain as recently as two weeks ago. Then, with increasing certainty, she declared that Guy was “the only person living who might have done the shooting.”3

As soon as word of this slipped out of the room, the waiting newspapermen bolted for the telephones.

*

Aloha was taken to the Carma and her arrival caused a flurry of flashbulb explosions and a volley of shouted questions, but Aloha refused to speak to anyone except Detective Miller. He took her to the community room where Walter’s body had been found, a small stain of blood still visible on the floor. He asked if she noticed anything unusual, to which she replied, “Everything.” Looking down, however, something did catch her eye. She bent down and picked up Wanderwell’s flutophone, his small tin whistle. “The police did not seem much impressed by my discovery, yet I knew things about the Captain’s flutophone that they did not know. The Captain had loved to construct these little objects, he had made them all around the globe, he had presented them to rulers in India, Negro chiefs in Africa, little boys in New York. He could play a nice tune on his flutophone and he loved to teach other people to play them.”4 Most importantly, though, Aloha knew the captain had always kept the instrument clipped to his wallet. “The spot where I had picked up the flutophone was about ten feet from the cabin door.” From this, Aloha deduced that Walter had reached for his wallet at some point shortly before his death — perhaps to pay someone off — but had been unable to replace the whistle. Aloha asked the police if they had located her husband’s wallet, and if a letter, written in Spanish, had been found inside. She was told that his wallet had been found, but there was no letter. Walter had always carried Guy’s mutinous petition with him, and she found it odd that the letter should be missing. “I thought this was interesting and important but the police did not seem to share my view.”5

*

By morning the story was in all the newspaper headlines, causing a sensation. This story had it all: love, travel, murder, whispers of sexual impropriety, jealousy, smuggling, espionage, a beautiful and mysterious widow, a scion of British nobility, and a disproportionate number of young, attractive girls. Less than twenty-four hours after the murder, newspaper articles and radio reports were already quoting Secret Service information revealing that Wanderwell’s true name was Valerian Johannes Pieczynski, that he had been interned as a German spy during the war, and arrested in 1925 for impersonating an army officer.

The Associated Press ran stories that read like summaries printed on the backs of pulp novels:

Mutiny, an attempted strangling and a fatal shot in the back, fired in the darkened cabin of an adventure yacht, were the clews [sic] detectives were following tonight in the hopes of finding the killer of Capt. Walter Wanderwell.

Globe trotter, suspected spy, and untiring seeker of the bizarre in life, Wanderwell, when felled by an assassin last night . . . left a murder mystery as keen as any of the adventures he sought in life.6

The pitch of high drama often came at the expense of accuracy. Some articles claimed that Walter specialized in cruises for “landlubbers to remote places” or that he was married three times: first to a Canadian girl named Gilvis Hall, then to an American named Nell Miller, and finally to a French girl called Aloha Wanderwell.7 Some articles presented statements as facts that are never repeated again. A United Press article made the sensational claim that “the pistol was lying on the floor at his feet. Fingerprints of the group aboard were taken to compare with those found on the gun.” The article even quoted the chief investigator, misnamed Lieutenant Ralph C. Witler (it was Miller), as saying, “he hoped fingerprints on the gun would clear members of the party of suspicion.”8 The presence of a gun directly contradicts every other version of the story as reported by the press, the police, and Aloha herself.

The murder of a world-roving, oversexed, mystery man was an interesting story, but it wasn’t long before papers latched on to the living spouse, Aloha.9 The Los Angeles Times recalled Aloha’s arrest and described her underage “escapades” of 1925. The competing Los Angeles Record branded her the “Granite Woman” and printed a sketch of a chisel-featured, empty-eyed woman beneath which they invited readers to “catch the cold glint of bravery in the face of this ‘granite woman’ . . . [who] wants the world to know that she comes of solid stuff.” Although supposedly an appreciation of a young widow’s ability to keep her wits in a trying situation, the article implied a kind of monstrous frigidity that came from being the wife of a man “schooled in German sturdiness.”10

By December 8 newspapers had widened their focus to include interviews with, of all people, Nell, who was now Mrs. Nell Farrell. In one paper Walter’s former wife said, “Walter’s murder was a terrible shock. I haven’t the slightest idea who could have killed him, but undoubtedly he had enemies.”11 Not to be outdone, two days later the San Mateo Times reprised the theme on page one, announcing “Former Wanderwell Wife in S.M. Says Girl is Killer.” Here Nell insisted that, “A woman, a woman of one of his adventures murdered Captain Wanderwell. He had it coming, and someone was bound to get him sooner or later.” Describing him as “the eternal lover,” Nell sighed that Walter might have become a great man had it not been for women.

My life with him was one of constant problems, difficulties, getting him out of scrapes, leaving town in the middle of the night so I wouldn’t have to testify against him. There were innumerable seduction and betrayal charges, and he was just slick enough, as a rule, to talk himself out of each.12

She even claimed to know William Guy, declaring that he was “innocent of the crime. I am positive of that. I knew Guy and I know there was no motive for him to kill Captain Wanderwell. A woman is the one to look for.”13 Nell had retired from the road a few years earlier, but her assertion, true or not, made for good copy.

*

A man named Harry Greenwood, employee of a local gambling ship, had been at the Long Beach docks on the night of the murder and reported seeing a man who fit the description of the Man in Grey. When shown a selection of photographs, he immediately pointed to the picture of Guy that Aloha had supplied. Greenwood described him as “an extremely nervous man who rushed from the vicinity of the Carma to a point a block away from the craft.” The man had asked how to get to the city centre, but after being shown where he could catch a street trolley, opted to run the distance. This report, combined with descriptions of Guy’s threatening visits to Wanderwell, made him the prime murder suspect.

What investigators could not understand, however, was why the Carma’s crew seemed so reluctant to share details about what they knew. Every answer seemed hedged, every description couched in the vaguest of terms. Exasperated, another detective, Lieutenant Murphy, announced that “certain persons, for reasons best known to themselves, have been withholding information from the police.” He warned, “Unless this attitude is changed, I will demand a grand jury investigation to determine if a conspiracy exists to cover up evidence.”14

*

On the night of December 8, Los Angeles detective Lieutenant Joe Filkas paid a visit to a house at 2054 Blake Street, in a district known as the LA River Bottoms. With him were two men, one of them Carleton Williams, the lead crime reporter for the Los Angeles Times. The house they wanted to search was dark and, judging by its ramshackle appearance, unoccupied. The men walked quickly up the steps and then Filkas kicked in the front door and shined his light on the interior. There, lying on a sofa eating tuna from a can, was William Guy. Far from looking startled, however, he simply put his hands in the air and with the faintest trace of a grin said, “I know what you want — I’ve been expecting you fellows. But I didn’t kill Wanderwell. I just moved here a day or two ago because I knew I would be suspected. I was thinking of giving myself up — I think I would have done it tomorrow but you fellows beat me to it.”15 When asked why he had gone into hiding, Guy freely admitted that he was in the country illegally and had even voted in the last election.

After his arrest, Guy was taken, not to the police station, but to the headquarters of the Los Angeles Times, where he was questioned by Carleton Williams and other Times staffers until the early hours of the morning. Newspapers would soon trumpet Guy’s own version of events, protesting his innocence, admitting his hatred for Wanderwell, and incredibly, claiming that no less than six people could prove he was nowhere near Long Beach on the night of the murder. According to Guy, he had gone to bed at 8:30 p.m. the night of the murder at the home of his good friend, the aviator Edward Orville DeLarm. Though Guy didn’t know it yet, Eddie had been the third man in the police vehicle.

When reporters had finished with him, Guy was brought to the Long Beach Police Department, booked, and then stuffed into a car and driven to the port of Long Beach. Wills, Zeranski, and others still living on board the Carma were asked to state whether they thought the man they had in custody was the Man in Grey. Guy smiled his glossy smile and looked at Wills through the porthole. “You know, I’m not a first class murderer,” he said. All present felt “pretty sure” Guy was the assailant. “I wouldn’t want to put a noose around any man’s neck,” said Cuthbert Wills, “but I think he is the man.”16 The crew was temporarily uncertain because, they said, the man who had appeared at the porthole was moustachioed and spoke with an accent that suggested a trace of German. Detectives, however, noted that a razor and shaving cream had been found at the rented house, and Guy himself admitted he had recently worn a moustache and that he was fluent in German.17

Within hours newspaper headlines announced the capture of the Man in Grey. The crew’s positive identification appeared alongside Guy’s own explanation of his whereabouts and details of why he had so disliked Walter Wanderwell. In his version of events, there had been no mutiny, but Walter and Aloha had simply abandoned the expedition in Colón, Panama. When Guy heard that Walter and Aloha were in Los Angeles, he paid them a visit and asked for his $200 fee to be returned since he had not, as promised, been delivered to the United States. Walter refused, smashing a window with his fist and calling for police assistance.

The cover of the Los Angeles Record’s “Extra” issue from December 8, 1932, features headlines about the Wanderwell murder and Aloha’s role.

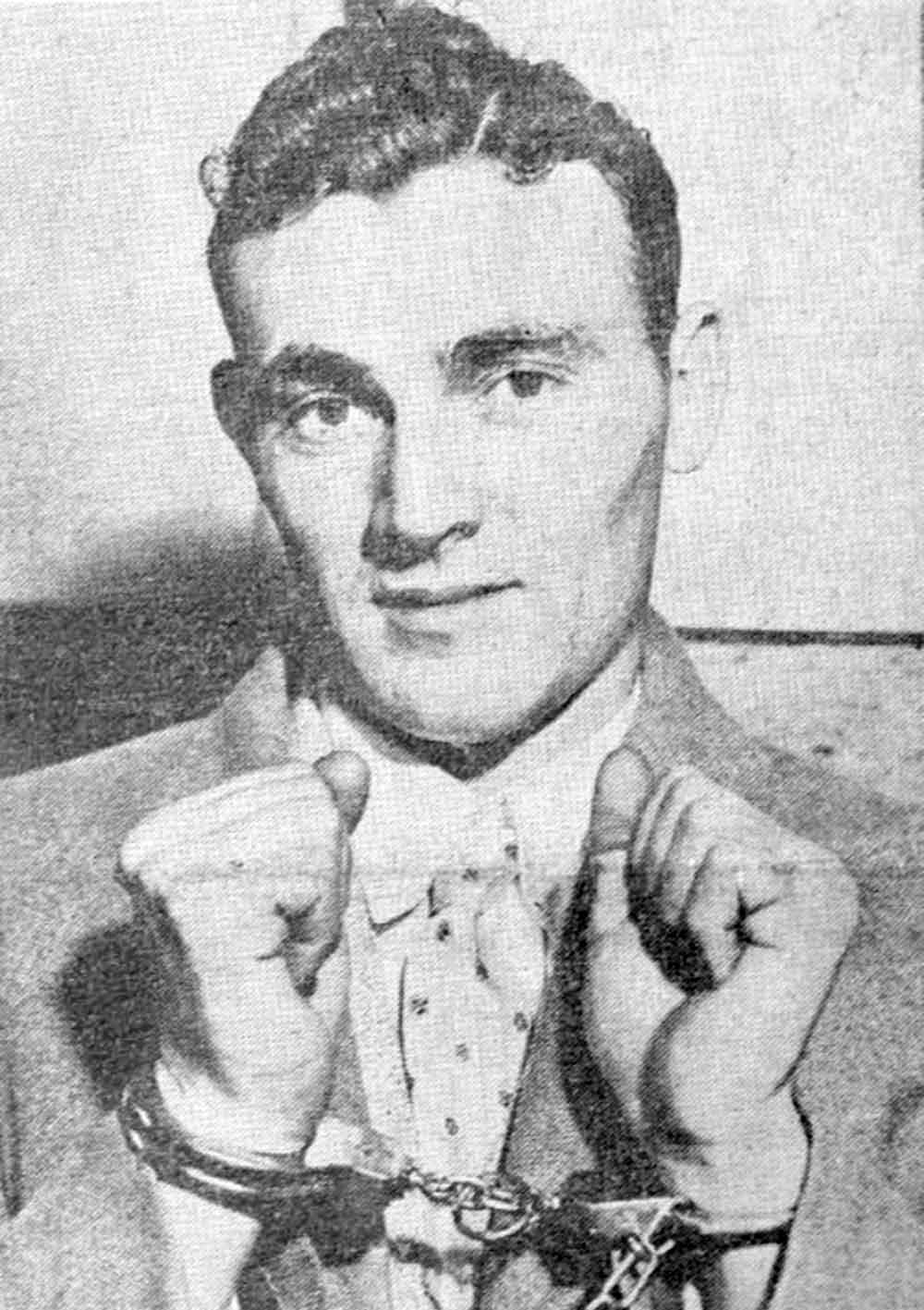

Circulated press photo of adventurer and defendant William James “Curly” Guy the day he was arrested and arraigned on first degree murder charges, Long Beach, California, December 1932.

*

Most of the Los Angeles–based dailies had crafted disparaging nicknames for Aloha, calling her “the Granite Widow” or “the Rhinestone Widow,” based on a necklace she had worn in the early days of the investigation. Ironically, it may have been a necklace of diamonds she had had made in Italy from stones she collected in Africa. And because crew members had been forbidden to speak to reporters, the press latched on to anyone remotely connected with the murder. One paper, desperate to heighten the drama, carried a front-page photo of the ship’s cat, Rasputin. A discouraged Long Beach policeman was quoted as saying, “If only this cat could talk.” The newspaper agreed, but noted that “Rasputin, with a cold, stony stare as icy as that of Aloha Wanderwell, the ‘Granite Widow,’ can’t put into words what he saw happen Monday night.”18

On December 8, 1932, the front page of the Los Angeles Record carried the headline “Murder Yacht Widow Breaks” and reported that Aloha “today broke under the strain of her husband’s murder and was reported in complete collapse.” Shortly after Guy’s arrest, police had asked Aloha to come to the station and confront the accused. Much to the press’s disappointment, Aloha reported that she was too ill for such a meeting. Earlier, a reporter had asked Miki how her sister could be so stoic. She replied that Aloha was working hard because everyone was depending on her. “If she did not act this way, the whole crew would go to pieces. There’ll probably be a big reaction later.”19

Despite the collapse of her personal life, Aloha had work to do. Voice-overs for the Bororo film had not yet been completed and an orchestra had already been booked — if she didn’t finish the recording, she would forfeit everything. So Aloha went to the Metropolitan Studios and narrated what turned out to be her last adventure with Walter Wanderwell. It was the worst performance she ever gave. Her voice, normally so lively and clear, was flat and muttering. She stumbled over her words but didn’t bother to correct them.

Aloha’s despondency did not go unnoticed. Douglas Fairbanks got in touch and reassured her that the best cure for a broken heart was to get working. He offered double billing with his latest picture Mr. Robinson Crusoe at the United Artists Theatre at Broadway and Ninth. Desperate for money, Aloha agreed. Walter had died without a will and their family funds were frozen until the estate could be settled. Within days, ads appeared for Fairbanks’s movie with an equally sized “special added sensation.” The specific wording of the ad, however, could not have been greatly encouraging: “The ‘Rhinestone’ Woman of the Hour! . . . Aloha Wanderwell In Person! . . . With Her Amazing Film ‘The River of Death’ Recording her last adventures with Capt. Wanderwell.”20

It was Hollywood voyeurism at its most shrill, but with Fairbanks’s help, Aloha was able to negotiate a generous fee. Engagements would begin on December 15 and run for a week. The ink was hardly dry on that contract before Aloha signed another with the Universal Service newswire to tell her life story. It was an opportunity to manage her image, while also raising interest in what the Wanderwell Expeditions had achieved through stories in short segments that would appear from December 12 to 15.

*

Circulated press photo of pilot and murder trial witness Edward “Eddie” DeLarm, Long Beach, California, January 1933.

Investigators continued their inquiry, looking for enough evidence to charge William Guy with murder. Subpoenas were issued for Eddie DeLarm and his wife, Isobel. Both claimed Guy was at their house at 325 Madison Way, Glendale, on the night of the murder — 30 miles from Long Beach. During separate questioning, however, Eddie and Isobel disagreed on when they had last seen Guy. Eddie stated that he “went to bed about 8 o’clock Monday evening, as near as I can remember. I think that Guy went to bed soon after. My wife remained up about an hour later. I don’t know whether Guy left the house or not.” Isobel wasn’t sure how late she’d seen Guy but asserted that “to the best of her knowledge” he was in bed when she retired at 9:00 p.m.21

Eddie denied that the Wanderwell case had been discussed with Guy the next morning. He said Guy had asked to borrow his (Eddie’s) Studebaker so he could look for a job. He “said he would return it to the Grand Central Airport, where I had my airplane in a hangar. I let him take the automobile and when I got to the airport about 10 o’clock the car was there and that was the last I saw of him.”22 According to Isobel, however, on the morning after the shooting, Guy and Eddie had driven away together at around 8:00 am.

Eddie told investigators he’d met Guy in Buenos Aires in December 1930 while “conducting some airplane flights.”23 He admitted that he had accompanied Guy on a visit to Wanderwell in August and that the incident had turned violent — directly refuting Guy’s claim. The most damaging reports, however, came from DeLarm’s mechanic, Ralph Dunlap, who had visited the DeLarm residence on the evening of the murder. He told police that Guy had been there and that he had even announced he was going to Long Beach, though he (Guy) refused to say why he was going.24

*

An inquest was held at 9:30 a.m. on December 9 at the Patterson & McQuilken Funeral Parlor. While crowds surrounded the premises, Aloha and members of the crew joined Long Beach police, William Guy, and state prosecutors to give testimony before a coroner’s jury. Carma crew member Marian Smith reiterated that she had seen the Man in Grey at the porthole, but now also added that she had seen him standing at the galley’s open doorway. “When the stranger came aboard the boat I saw him the first time as he halted momentarily at the doorway. . . . I had a good look at him at that time. A moment later I had another look at him when his face appeared at the porthole to the dining room. I am positive the man I saw is the man here.”25 After making her announcement, Miss Smith fainted.

Next were Cuthbert Wills, Ed Zeranski, and Mary Parks, all of whom agreed that Guy was the man who had visited the Carma Monday night. To everyone’s surprise, however, Deputy district attorney Clarence Hunt refused to allow a charge of murder to be brought against Guy. The reason, according to one reporter, was that, “Not once was the name of the suspect brought into the testimony.”26 The coroner’s jury, however, did agree that Wanderwell had died from “gunshot wounds inflicted by an unknown person on the ship Carma,” and that, “from the evidence produced we find the killing to have been with homicidal intent and we recommend further investigation.”27 In fact, evidence of powder burns on Walter’s jacket showed that he’d been shot from a distance of about six inches.

*

On the morning of Monday, December 12, Aloha was getting ready for the trip to Long Beach Harbor, where Walter’s funeral was scheduled to begin at 9:00 a.m. Before she could leave, however, the police were, once again, knocking on her door.

Deputy District Attorney Clarence Hunt questioned Aloha for more than two hours, forcing her to recount every aspect of the trip to South America, of Guy’s desertion and threats. What, exactly, was Guy’s motive for killing Walter? Why not just rob him or beat him senseless? When Aloha was finally permitted to leave, she stepped into the corridor and collapsed. According to the Associated Press, “Authorities said they had questioned Mrs. Wanderwell only about Guy’s past and his connection with the Wanderwells.” The article also noted, however, that “what was brought out during the questioning of the attractive blond widow and what caused her to falter and swoon into the arms of her sister was not made known by officers.”

The failure to bring a murder complaint against William Guy had become an embarrassment to the Long Beach police force. Aloha was brought to the station to extract as much information as possible to bolster their case. When they were done, warrants were issued for the arrest of both Eddie DeLarm and his mechanic Ralph Dunlap — as material witnesses for now, but with the possibility that they could be charged as accomplices to murder.

With Miki’s assistance and her head held high, Aloha left police headquarters, telling reporters only that she had a husband to bury.

*

The body of the slain Walter Wanderwell, traveller of the world’s long trails, went to an ocean grave under a brooding storm.

Cold rain fell, thick fog lay over the harbor, and a chill wind furrowed the waters as the little schooner, on which the adventurer had been shot in the back just a week ago, put out in an angry sea.28

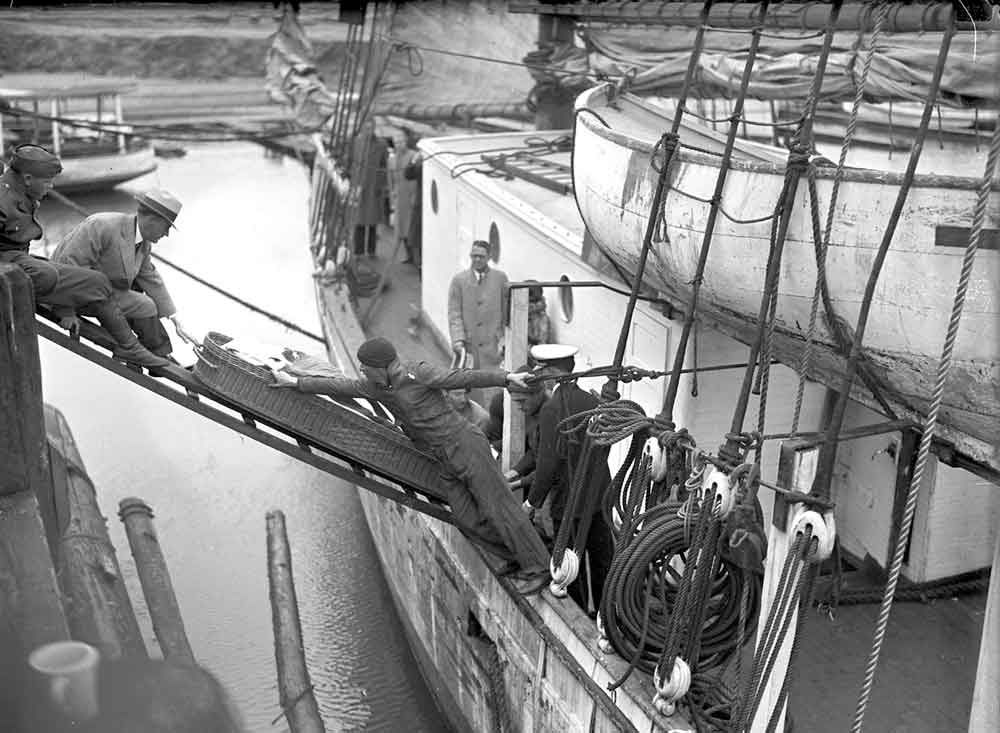

So the newspapers described the Carma’s sad trip into open waters. Befitting the proceedings, it was even snowing slightly. A crowd of men in long coats and fedoras had gathered at the dockside, waiting in the gusting rain for the widow to arrive. Walter’s body, laid out in a sea grass coffin and draped with the American flag, had been carried from the hearse and lowered to the deck of the Carma. Among those waiting, only Eric Owen wore a Wanderwell uniform.

When Aloha arrived, in uniform and with a black veil of mourning across her face, the procession began. In most photographs she looks frozen. One shot captures an expression verging on grief, her hand stretching to touch the sea grass coffin.

The seagrass casket containing the body of Walter Wanderwell is lowered onto the deck of his beloved Nova Scotia schooner, Carma, in preparation for his burial at sea, Long Beach, California, December 12, 1932.

The Carma motored several miles west towards Santa Catalina Island over choppy seas. Captain Farris, a tall handsome man with a booming voice, read out a short speech on Aloha’s behalf. He recalled Walter’s many achievements, the values he fought for, and the country he loved. Aloha stood next to the flag-draped coffin that rested on a plank pointing over the railing. Eric W. Owen stood beside her, bugle in hand, while just over her shoulder was Art Goebel. As the Carma heaved on the unsteady seas and the rain mixed with snow, the eulogy ended with a short quote from Walter’s favorite countryman, Joseph Conrad:

May the deep sea where he sleeps now rock him gently,

wash him tenderly, to the end of time.

Captain Farris closed his book, a seaman’s whistle sounded, and Eric Owen raised his bugle to play a final “Taps.” Attendants lifted the plank and Walter’s coffin slid into the water. A wash of bubbles frothed and dispersed as the casket receded into the sea. After a life on the road, a million vagabond miles, and who knows what else, Walter Wanderwell was gone.