TWENTY-TWO

CLOSE QUARTERS AND FRIGID SEAS

In February 1932 the Winter Olympic Games took place at Lake Placid, New York. Crowds flocked to watch contestants from seventeen countries compete in speed skating, Nordic skiing, bobsleigh, ice hockey and, most popular of all, figure skating. Audiences gasped as Sonja Henie gave a flawless performance, sweeping her way to gold and into the record books. At only twenty years old, Henie had already won gold at the 1928 Olympics and five world championships. Newspapers gushed that “for perfection of figures, grace, showmanship, and mastery of the most difficult spins and jumps, there appeared to be no real competition for her.”1

Henie’s performance was the gloss on a very successful Olympics, but this was a rare patch of blue in an otherwise dark sky. Even during the games, front-page headlines blared alarm at the nation’s destroyed economy. In the time that Aloha and Walter had been away, nearly five thousand banks had collapsed, the nation’s productivity had fallen some 30 per cent, and industrial stocks had shed nearly 80 per cent of their value.2 By 1932 half of all workers in Cleveland, Ohio, were jobless. And in Toledo, Ohio, four out of five were jobless.3 Many blamed President Hoover for the nation’s economic woes and public anger would soon sweep him from office, replacing him with Franklin D. Roosevelt, the man who would become the longest-serving president in US history.

*

The economy in Mexico, though hardly robust, was faring better than America’s. After checking that their savings still existed in the US, Walter and Aloha elected to stay in Mexico for a while. Years later, Aloha would still wonder that among so many bank closures, their account in Florida was somehow intact.4

Using Nogales, Mexico, as their forwarding address, Aloha began contacting various offices of the Shell Petroleum Corporation in Seattle, St. Louis, Denver, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. Long a major sponsor of the expedition, they had used Shell’s distribution network to assist with the shipping of various pieces of equipment and collateral. This time Aloha asked that all available Wanderwell pamphlets (more than 35,000) be sent to Mr. F.M. Schlegel of the Shell Petroleum Company in Los Angeles. By late March, the Shell-sponsored pamphlets were concentrated in a Shell warehouse at 1298 Alhambra Avenue, and Aloha and Walter were ready to begin.

The original plan had been to work theatres all the way to Canada, collect the children, then return to Hollywood to edit the South America films. But given the “Hoover wagons” that lined California’s streets, Walter was leery about their chances of earning much. There were more beggars here than they’d seen in India, and the highways were lined with stands selling anything: teacups, shoe shines, scrap wood, empty milk bottles, rescued nails. He and Aloha decided to head for Canada first, then work their way back. At least this was the scenario that Aloha painted in her memoirs. But there was another major issue hounding them: those 35,000-plus pamphlets were evidence of another failed venture.

The latest pamphlet had been one of the largest and most descriptive of any the expedition had produced, and why not — Aloha and Walter had spent years travelling the globe, and now there were many WAWEC units scattered across it. This act of WAWEC franchising was a masterful feat of marketing, and they had every right to be proud. On the back cover of the warehoused pamphlet, Walter had advertised the “first WAWEC Jamboree.” It was a rallying cry to all WAWEC worldwide members to attend, and it was to be held at their “Camp Wanderwell” headquarters in Miami in December 1931. This would have been the first and largest collection of expedition crew members present anywhere and would be a confirmation of Walter’s long-held dream.

But there was a problem: it was now early 1932, and Walter and Aloha hadn’t attended. They couldn’t have; they had been stuck in South America, dealing with their failure to complete the continental crossing and sorting out the ramifications of their crew’s rebellion. For the founders of both the Wanderwell Expedition and WAWEC to simply not show up at their own convention would have raised holy hell among the hundreds of WAWEC members who had offered their trust (not to mention thousands of dollars in fees) in the cause. With this failure dogging them too, Aloha and Walter headed for Vancouver Island in British Columbia. It was the first time in the Wanderwell Expedition history that they did not stop in town after town to sell pamphlets and postcards or present their films. Their trip north to Canada looks very much like an extension of their lying low in Mexico.

*

On a sunny day in early June, the sound of crunching gravel sent six-year-old Valri Nell Wanderwell racing out through the front door of her grandmother’s house on Vancouver Island. Barefoot, she ran to the edge of the yard and watched the familiar car with its wonderful letters emerge from the forest trail leading to the house. After two years away, Mom and Dad were back and their arrival was certain to bring hugs, kisses, and presents.

From the porch, Valri’s five-year-old brother Nile, always more reserved than his vivacious sister, watched as the car doors opened and the grown-ups stepped out. Soon, the tall lady he knew was his mother had swept a giggling Valri up into her arms. Reaching into the car, his mother pulled out a white stuffed toy rabbit and gave it to Valri. Now Grandma and Tia-Miki were there too, hugging and shaking hands with the new visitors. Then the man dressed like a soldier strolled over and crouched down. He looked into Nile’s eyes and smiled, holding out his hand. On it was a small toy car, a blue racer, and a silver coin with a flying bird on it. The boy took the gifts and mumbled, “Thank you, sir.”5

Before long, the adults were sipping tea in the dining room. Aloha told tales of South America, recalling the Bororo tribe, their strange customs, their habit of living naked and swimming in piranha-infested rivers. She described the wonderful Junkers F.13 and the fuel leak that had sent them down. The footage, Aloha boasted, was unlike anything seen in theatres before. This film, when it was done, would cement her place in history. Miki sighed and said she was ready to get out and see something — like the sun. It had been a long dark winter in British Columbia.

“Well, why not come to Los Angeles?” Aloha suggested. The South America footage would take time to edit, so it would be lovely to have someone to help watch the kids. Perhaps Miki could even look into starting a career in Hollywood. It was decided.

*

After two weeks, they said goodbye to Margaret and headed south. In Seattle they added three new members and, much to Aloha’s disgust, purchased yet another car — a 1928 Cadillac. Among the new crew members was diminutive twenty-year-old Dorothy Dawn, a prettier version of Olga, who acted as backup driver and assisted with publicity. Another girl, sixteen-year-old Lynette Pollard, from nearby Tacoma, was unable to join the tour immediately but promised to travel to Los Angeles as soon as she was able to provide the $250 deposit required to join.

*

When Walter told Aloha of his idea to purchase a schooner for a South Seas expedition, she was speechless. Since their arrival in the United States, Walter had droned on about the need to shore up their finances, to proceed with caution, to redouble their efforts. Now he had purchased another car and wanted to squander what remained of their savings on a boat? What about her film? Editing alone would cost a fortune.

Walter explained that having a boat would safeguard their lifestyle and provide a ready means of generating income. More than that, he wanted it to be the headquarters of a new organization he would legally register: the International Police, Inc. Aloha was unmoved. Walter described how by incorporating the international police he would be setting a legally verifiable precedent for the idea and also have a more stable means of creating and preserving value from their travels. It was, he assured her, the logical next step in the evolution of the Wanderwell Expedition. From now on, the sole focus of the expedition would be to further the international police idea and its originator. It was, in other words, the end of Aloha as the face of the expedition.

On July 5 an Associated Press article noted that Captain Walter Wanderwell and his wife had arrived in San Francisco after driving from Buenos Aires. On July 20, the San Jose Evening News announced that Walter Wanderwell had returned to their city after a sixteen-year absence but that he wouldn’t stay long because he planned to “continue moving as long as he lives.”6

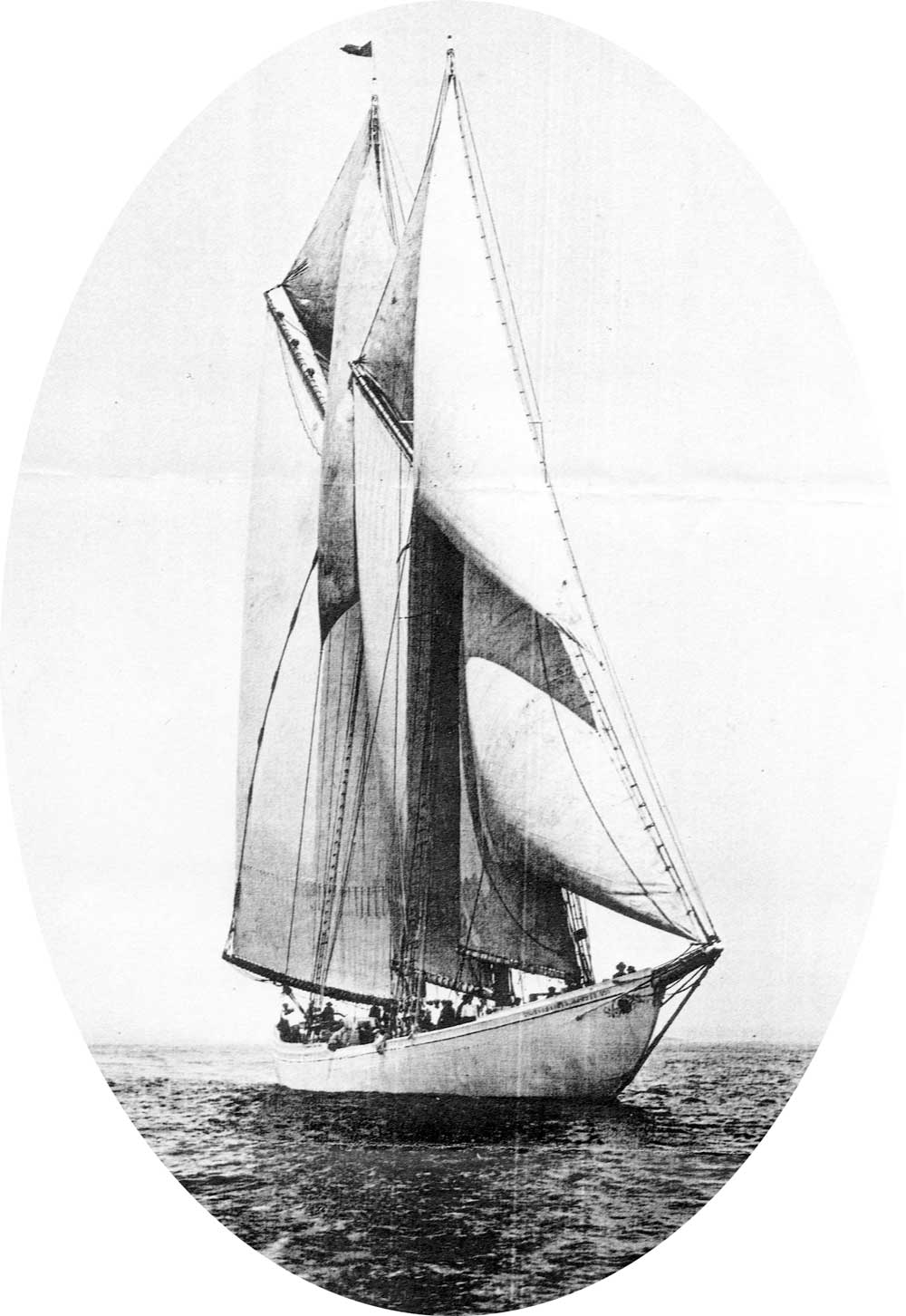

According to a postcard Walter sent to his brother Janec, the expedition was travelling with a Cadillac, a Ford, and a house trailer en route to Los Angeles. He wrote, “business here is very tight. Bartering is very popular now and especially for our own needs. Actual cash is extremely limited.”7 Yet he was also hopeful that a schooner named Carma would soon be ready for a trip to the South Seas. The Carma was a sleek, fast, 110-foot, two-masted schooner. Originally christened the Norma P. Coolen in Mahone Bay, Nova Scotia, in 1913, her early days were spent trawling the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, where she gained a reputation as one of the fastest ships in the area. Over the years she was owned by a procession of dreamers and schemers, each failing in their plans for the boat, thanks to malfunction or misfortune. One day, during a routine fishing trip, the ship was caught at the edge of a sudden violent storm. The captain trimmed the sails and attempted to head home with the day’s catch but was overtaken by the storm. A violent gust sent the main mast crashing to the deck where it killed the captain. Later, when Prohibition took effect, the Norma P. Coolen was sold to a French liquor syndicate that renamed her Cherie and began running booze between Canada, America, and the French islands of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon off the south coast of Newfoundland. Later, she became Carma. She was eventually seized by the US Coast Guard and sold at auction. The last owner had planned a trip to Vladivostok, but his plans were scuttled by Soviet red tape and the stock market crash.

Walter contacted the ship’s current captain, Haakon H. Hammer, and inquired about purchasing the ship for a South Seas cruise. Hammer said that the ship needed extensive repairs but that a group of Scandinavians had rented the boat to take fishing parties down to Mexico. The group had paid one month in advance and had promised to make required engine repairs. If Walter could wait for a month or two, the ship might suit his purposes. Walter agreed.

*

By August 11 the Los Angeles Times was reporting the triumphant arrival of the Wanderwell Expedition all the way from Buenos Aires, unaware they had already been to Canada and back again. Unsatisfied with their own “world’s record for touring,” the article explained how the expedition had come to Los Angeles to prepare for a “schooner trip to South Seas Isles and a journey through the eleven countries not already crossed by the intrepid organization.”8 The articles, clearly arranged by Walter, made no mention of a forthcoming film or of theatre engagements or of Aloha.

Aloha sniffed around Hollywood until she found suitable lodgings: two adjoining suites, located at the Arcady Apartments on the corner of South Rampart and Wilshire Boulevard. It was not an ideal location, but would do until they could find something closer to the film labs in Hollywood. For Aloha, the apartments were a place to sleep and to store the children while she worked. But rumours had begun to swirl. By some accounts, Aloha and Walter were no longer getting along and were in fact sleeping apart.9 She later said the second suite was occupied by former expedition members, including Eric Owen.

Whatever the climate of her relationship with Walter, Aloha’s infatuation with the world’s entertainment capital was undiminished. It was the place where things happened.

Particularly in 1932, the Summer Olympics. More than 100,000 people had flocked to the opening ceremonies of the Games of the X Olympiad, held at the Olympic Stadium (now called the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum). There was every reason to believe that the influx of visitors to the city could be a boon to the expedition’s sales of their newly revised pamphlets, but the apartments Aloha had rented were only a few blocks from the Chapman Park Hotel, where female Olympic athletes were being housed. The crush of reporters, tourists, and official traffic made driving next to impossible and badly hindered pamphlet sales: without a place to showcase the cars, the Wanderwells were just grifters in funny costumes.

When the games ended, Aloha set about editing her film. Mindful of the criticisms levelled at With Car and Camera Around the World, she made certain that she was not in every scene and that the story was more than just a gander at the Mato Grosso. The search for Colonel Fawcett, the downing of the plane, the jungle’s perils, and the “savage” Bororo tribe would supply enough drama to carry the story. But there was no doubting who the hero of the film would be, or of its greater purpose: this was Aloha’s best chance to become a star.

*

Aloha returned to her apartment one afternoon and heard shouting in the adjoining suite. Then a cry for help. She ran into the hallway and banged on the door. The noise stopped, and moments later, the latch fell and the door swung open. A dark-haired man stood at the threshold. Chairs and a table had been overturned. Two expedition members stood in a corner and near an open window she saw Walter, his hair ruffled and his clothing in disarray. Then “a man stepped from an adjoining room and I saw that it was Guy. Everyone was talking; someone said that Guy had demanded money that the Captain owed him. I heard the Captain say: ‘You can’t blackmail me; you can’t choke money from me that I don’t owe.’”10

Eyeing Aloha, Guy seemed to change his mind. He motioned to his friend and the four men brushed past Aloha and left. Appalled, Aloha insisted that Walter contact the police, or better still, the immigration authorities. But Walter refused. Straightening his tie, he said that Guy had demanded the mutinous declaration written in Panama, as well as the money he had paid to join the expedition. When Aloha worried that Guy might return, Walter shook his head. “Guy’s a young fellow, he’s hot-headed and later he’ll realize his mistake. If he is in the country illegally he will be caught sooner or later.”11

One of the men accompanying Guy that afternoon was the American aviator Edward Orville DeLarm.

*

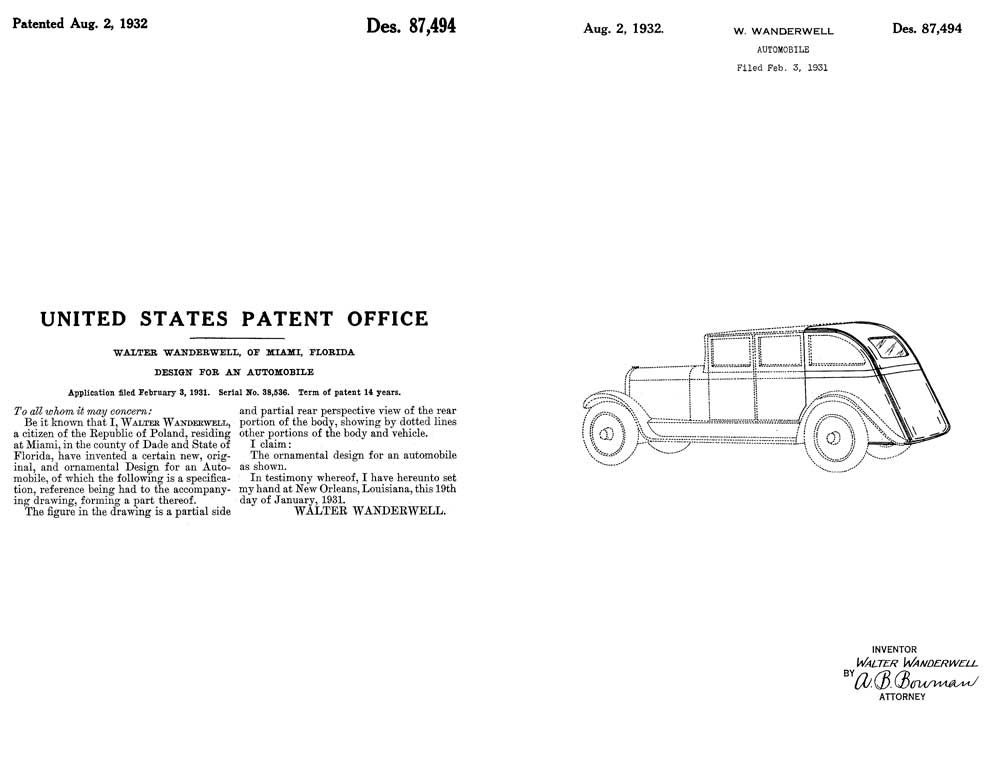

Towards the end of August, Walter learned that the US Patent Office had approved his claim to an “ornamental design for an automobile,” awarding him a patent for a term of fourteen years.12 The design showed a car with a rounded back, looking much like the sloped, aerodynamic cars that Cadillac would begin producing in 1934 and would evolve into a hallmark of 1930s automotive design. At about the same time, Walter began his submissions to the Division of Corporations of the State of California — the first step towards establishing the International Police, Ltd., a company that would be legally permitted to issue and sell shares.

Walter Wanderwell’s official papers for his aftermarket Speed Slope for automobiles, dated August 2, 1932.

The Wanderwell Expedition’s schooner Carma under full sail, Long Beach, California, November 1932. This picture was framed and sitting on Valri’s coffee table when the authors visited her in Honolulu.

While continuing to push forward, Walter heard that the schooner he intended to purchase had been seized off San Clemente Island, and its captain, a man identified only as Kollberg, arrested for transporting several hundred cases of whiskey, purchased from a Canadian boat in international waters.13 Walter scrambled to find a replacement ship but called off his search on September 18, when District Judge McCormick condemned the vessel and ordered it sold at auction to satisfy a fine of $2,200 — less than half the purchase price Walter had originally agreed to. The ship’s owner, Mr. W.L. Doyle, protested saying that Kollberg was not the ship’s owner, but the judge was unmoved and ordered the sale to proceed.

On the morning of October 5, a large crowd gathered at the county courthouse to attend the federal auction. Walter, Aloha, and the children pushed their way into a row of seats normally reserved for criminal trials. By the time United States Marshal Albert Sittel announced bidding on the former rum runner, Walter was wiping the palms of his hands on his thighs. This was by far the largest purchase he had ever attempted. The room fell silent as proceedings began. As promised, the bidding for the schooner opened at $2,200. Walter indicated that he would meet that price. The marshal then raised the price to $3,200. Walter waited nervously, but there were no takers. The Carma was declared sold, after just one bid, to Walter Wanderwell.

On October 7 the Harbor Shipping section of the Los Angeles Times announced that Captain Walter Wanderwell was seeking a crew of about twenty for a cruise to Tahiti “and away places.” Within days, applications were pouring in from as far away as New England. Some people offered to pay extra while others cited long and formidable lists of skills and qualifications. Walter soon realized he could charge far more than the original $50 they had advertised. The price was raised to $200 (enough to cover the boat’s entire purchase price) and planning for the expedition began in earnest.

Aloha suddenly had more to spend on the Bororo film, allowing for animated maps, proper film titles, and for the first time, a narrative soundtrack. It would be expensive but with a soundtrack, it would be possible to send the film into wide distribution, delivering her name to a multitude of new audiences while simultaneously freeing her from the stage.

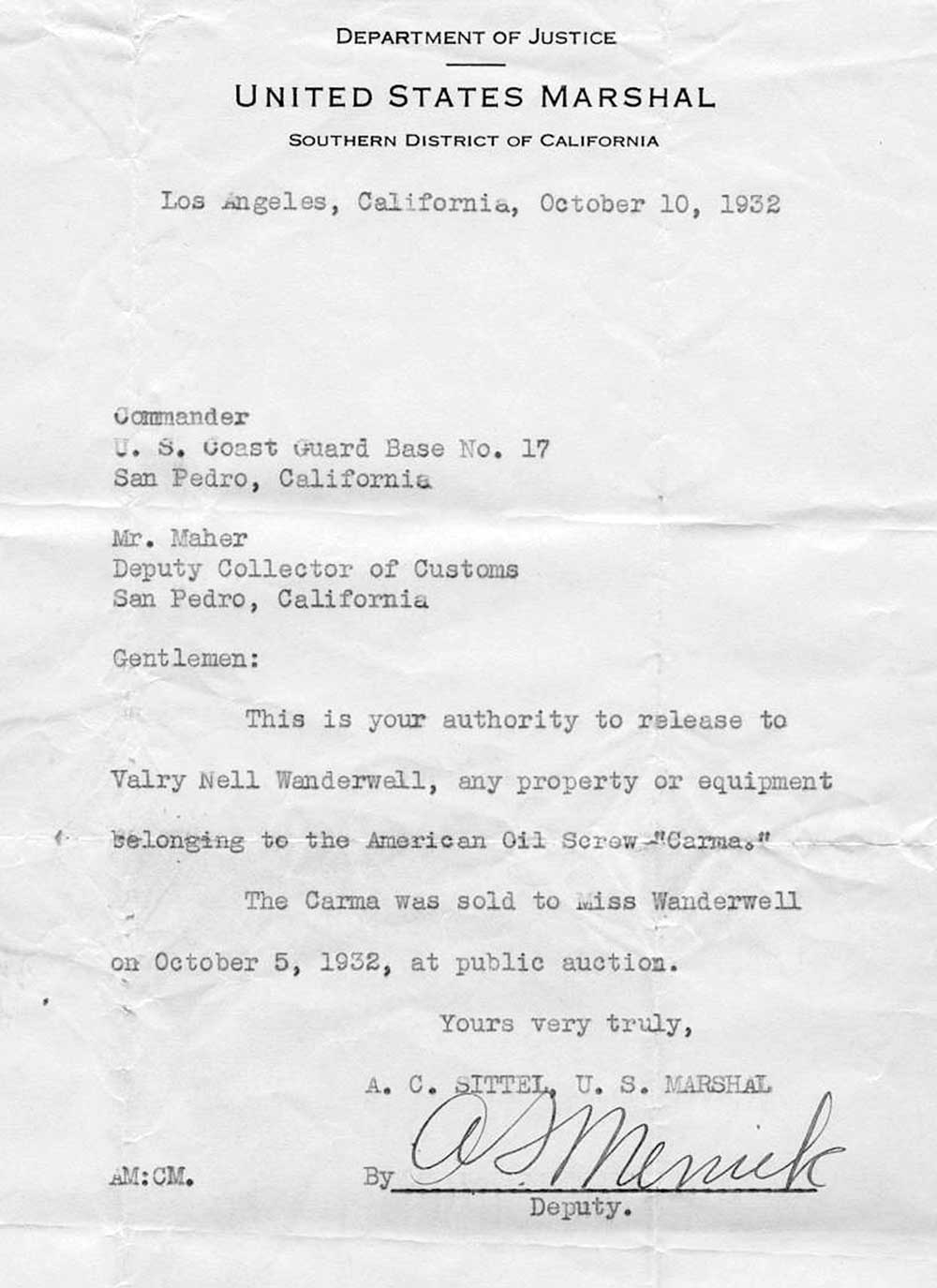

Three days after the Carma’s auction, Judge Paul John McCormick learned that Wanderwell was not an American citizen and, therefore, not legally entitled to purchase at government auction. The sale order was rescinded and Walter’s money returned. It didn’t take long, however, for Walter to untangle these latest knots. With the assistance of attorney David H. Cannon, he told the court that the boat had been purchased on behalf of his daughter, Valri. Naturally, those attempting to prevent the ship’s sale raised a howl of protest — who would buy a 110-foot schooner for a six-year-old girl? Nonetheless, on October 10, Judge McCormick ordered the sale to proceed. An article in the following day’s Los Angeles Times pronounced “Valry [sic] Nell Wanderwell . . . the youngest master of any vessel plying the Pacific Ocean, according to Deputy United States Marshal Minnick.”14

US Department of Justice letter releasing the Carma, purchased “illegally” only days earlier by Walter, into the hands of his daughter, Valri, the only American of the bunch, Los Angeles, California, October 10, 1932.

Coincidently, on the same day the court released the Carma, Walter received a letter from the Commissioner of Corporations informing him that the IP project was now legally registered in the state of California as International Police, Ltd. In the space of a few hours, the Wanderwells had set a new course for themselves.

*

Aloha’s reservations about the ship vanished once it actually became theirs. On a sunny morning, the Carma was officially released to Valri, in the care of her parents, and the family climbed onto the boat. “We loved [the Carma] from the first day,” Aloha said. “We thought it would give us the happiest days of our lives.”15

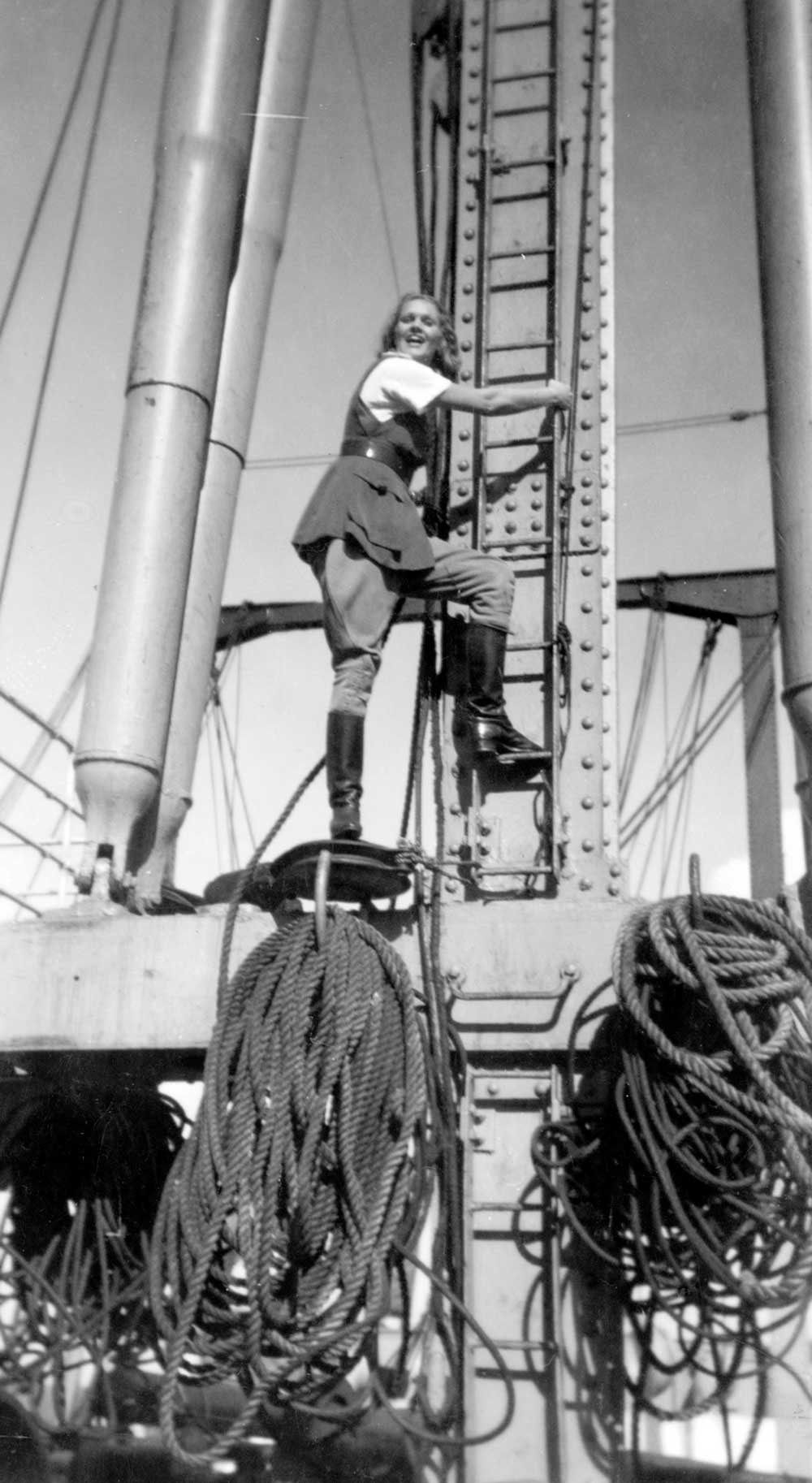

The Carma was taken to the P&O docks at the Long Beach Marina for a month-long refurbishment. The troublesome diesel engine would be overhauled, rotten timbers replaced, and the ship furnished. Within days, the Carma’s railings had been repainted a gleaming white and the words “International Police R.E.,” standing for the International Police Research Expedition, had been painted on the bow. A smiling Aloha posed for photographs with the children, looking out to sea from behind the wheel or grinning from high in the riggings.

While the boat was overhauled, Aloha and Miki rented an apartment in Hollywood closer to the film lab and paid visits to Hollywood studios and distribution companies. Walter began sorting and hiring new crew members.

*

On October 27, the first meeting of the shareholders of International Police, Ltd. took place aboard the Carma.16 Because neither Walter nor Aloha were American citizens, the organization’s founding members were listed as Carma crew members Eric Owen (president), Cuthbert Wills (secretary), and Cuthbert’s wife Elsa G. Wills (treasurer). Evidently, founding a company was not something six-year-old Valri was legally permitted to do. Cuthbert, called “Bert” by family and friends, was an English-born sailor, tall and lanky, with a pencil-thin moustache and a sceptical, mildly fastidious expression. He was a relative of Australian explorer William John Wills, who in 1860 led the first south-to-north crossing of Australia, from Melbourne to the Gulf of Carpentaria. A naturalized American, Wills had recently married Elsa, a girl from Guyana, and the Wanderwell Expedition was to mark the beginning of their adventuring life together.

Aloha about to climb into the rigging aboard one of the expedition’s many transoceanic ship excursions, undated.

Aloha’s plans were finally coming together too. In mid-November she met a young film executive named M.J. Kandel, president of Ideal Pictures Corp., a film distribution company with offices across the country. Kandel was interested in the Bororo film and even more interested to know that further films were forthcoming. In 1933 Ideal Pictures was about to release a documentary called A Jungle Gigolo, written by A. Carrick and F. Izard, about the trials of a man living on the island of Sumatra with more wives than he can support.17 Another drama called Found Alive told the story of a boy who had been hidden in the jungle during a messy divorce, only to grow up and discover the “lure of savage passions.”18 The Wanderwell films, with their exotic locations and thrilling sequences, would fit nicely into the company’s plans.

*

Of those who had applied to join the crew of the Wanderwell International Police Research Expedition, twenty were provisionally selected and fifteen might actually sail. Among the crew were the sisters Mary and Marian Smith of Rockmart, Georgia; Mary “Nellie” Parks, a twenty-six-year-old schoolteacher from Boston; and in a most bizarre piece of casting, an English nobleman, Lord Edward Eugene Montague, second son of the Duke of Manchester.19 Several members came as a result of ads placed in the Seattle and Portland newspapers, including James E. Farris, who would act as ship’s captain; his fiancée Ruth Loucks; and student sailor Jack M. Craig. The only familiar name was Eric Owen.

It was not long before federal officials were back causing trouble for the expedition. Following the US Marshal’s condemnation of the Carma as “about as seaworthy as a cardboard box,” naval authorities threatened to put a stop to the proposed expedition, citing the ship’s unseaworthiness and insufficient life-saving equipment.20 In fact, there was only one rowboat, hardly big enough for three people, never mind fifteen or twenty. Walter once again stepped in, revealing once more how careless he could be about the safety of his crew. He pointed out that he was not selling passage aboard the Carma, he was casting about for working crew members and, as such, they were all exempt from US transportation laws. Authorities were powerless to prevent the voyage from proceeding.

The charge that the ship was not seaworthy shook several crew members, including Aloha. She asked Walter to delay the trip and to purchase adequate life-saving equipment for the vessel. At the very least, Walter should chart a course that kept them close to land for as long as possible. Walter flatly refused. They would set sail for Hawaii, a crossing of more than 2,400 miles through open sea. There they would take film and earn money lecturing before continuing on to Polynesia, Tonga, Fiji, New Zealand, and Australia.

On November 29, Eric Owen and the Willses resigned their directorships with International Police, Ltd.

*

By Sunday, December 3, the Bororo film was nearing completion. A few scenes needed to be edited, some voice-overs added, and the titles completed; however, there was more than enough to show Ideal Pictures. Because it was Sunday, the film lab was closed, so Aloha travelled the 30 odd miles from Hollywood to spend the day on board the Carma, visiting the kids who were now living on board the vessel. Although the ship was hardly in pristine condition, it had come a long way since auction day. Broken furniture and empty boxes had been cleared out, all the rooms had been freshly painted, and new furniture installed where necessary. Each room was decorated in the style of a different country, reflecting the international flavour of the ship and her crew. A long table was installed in the galley and a piano and a gramophone were placed in the community room — shades of her stepfather’s Inlet Queen — along with a comfortable sofa, a divan, and a small library. Foodstuffs, tools, drinking water, cameras, pamphlets, a small printing press, thirty rifles, and ample ammunition had all been securely stowed below.

Late in the afternoon, while most of the crew continued cleaning and tinkering, Walter called Aloha to their cabin. She later said that he told her that one of his pistols was missing — a .38 calibre revolver. The gun had been in a locked chest, but the chest had been opened. Together they combed the ship and asked crew members if they had seen the gun. No one had. A number of crew members were sent into town by Walter to canvas pawn shops. After more than an hour of looking, they gave up. The pistol had vanished.

*

The following Tuesday, December 5, Aloha was back in Hollywood working on the film soundtrack. The Carma was still docked at Long Beach, ready, at long last, for her South Seas voyage. A fifteen-member crew had been selected, supplies and fuel had been gathered, and newspapers in Hawaii had been alerted to the expedition’s arrival sometime within the month, depending on wind conditions. All that was left was to repair the ship’s interior lighting, and for that an electrician had already been hired.

December’s arrival meant cooler temperatures even in Southern California, and by evening, a fog had crept over the coast, haloing the single light on the dock near the ship and magnifying the watery sounds of the harbor. There was nothing left to do aboard the Carma so most of the crew decided to go to a movie. Several new films were in theatres, including the Marx Brothers’ Horse Feathers and a Betty Boop short called I’ll Be Glad When You’re Dead You Rascal You, featuring a score by newcomer Louis Armstrong and his orchestra.

Four members stayed behind to watch over the ship and the kids. When Valri and Nile had been put to bed, Walter gathered with Ed Zeranski, Cuthbert Wills, Marian Smith, and Mary Parks in the ship’s galley, where they played rummy and discussed plans for the morning. At some point a discussion arose regarding the sailing distance between two ports, and unable to agree, Walter headed for the ship’s community room, presumably to retrieve a book or some maps. Shortly afterwards, a man appeared at the screened porthole outside the cabin. He asked the crew members where Captain Wanderwell was.

Wills stood up and walked to the galley door, where the fellow was now standing — a middle-aged man dressed in a long grey coat. Wills asked if he was the electrician.

Oddly, he replied, “No, but I know a lot about electricity.”21 Wills would later say the man spoke with a German accent. He asked again where the captain was. Wills led the stranger along the deck to the community room, where Walter was still looking for a map. The man thanked Wills and stepped inside. As Wills walked back to the galley he heard the captain greet the man in a tone that suggested surprise but familiarity.

Walter Wanderwell lays dead from a single bullet wound to his back, slumped against the divan of his stateroom on board the Carma, Long Beach, California, December 5, 1932.

In the galley, Wills re-cranked the phonograph, set the needle on “St. Louis Blues,” and resumed his seat at the card game. According to his later testimony, he had just picked up his cards when there was a shout from somewhere outside. Mary craned her neck to look through a porthole; perhaps there was a party in the harbor. But then there was a muffled pop followed by a high shriek so loud it seemed to come from just outside the door. Wills and Zeranski threw down their cards and raced from the cabin. They hurried up the ship’s ladder to look over the wharf. With only one light on the dock competing with the thick fog, they could see no one. Perplexed, they climbed down and combed the ship’s deck, looking for anything unusual, but all was in order. The children were still fast asleep, and the moorings were tight. Then Wills noticed that the door to the common room was ajar. Zeranski reached down to light the kerosene lamp, but even as his matchstick crackled to life it was clear that something was terribly wrong. The captain was sitting on the floor, slumped against the divan. Two streaks of blood ran down the back of his jacket, issuing from the spot, about mid-back, where a bullet had smashed its hole and tore through his heart. Wills and Zeranski rushed into the cabin. Captain Walter Wanderwell was already dead.