TWO

BRAINS, BEAUTY, AND BREECHES

By June 1919, seven months after the last shot, the war to end all wars finished with the signing of the Treaty of Versailles. That same month, after a lengthy train trip from Vancouver Island, Idris stood on the shuddering deck of the SS Melita, watching the ship’s propellers churn the cold Atlantic waters. She was twelve years old, and she was travelling solo to England. It had been three years since she had last seen her family. Never small for her age, Idris now stood at almost five seven. Her face had thinned and lengthened, revealing strong cheekbones, large, deep-set eyes, and full lips. The biggest change, however, was in her attitude. Idris had always been a high-energy child and boarding school had proved an intolerable prison of starched collars and chalkboards. The only thing that had made her dull life bearable was the cinema. On the silver screen, Hollywood’s stars led exciting and glamorous lives. And in 1919 no one was more glamorous, more adventurous, or more famous than Canadian actress Mary Pickford. Idris became obsessed with Pickford’s persona, copying her spunky style, her bravado, and her disregard for authority.

Idris’s ship departed from Montreal and sailed for eight days. Like Idris, many passengers were returning to salvage the scraps of their former lives or to claim the possessions of lost relatives. But there were other worries too. Since the war’s end, a new and vicious strain of flu was sweeping the globe, killing with incredible speed. An innocent sneeze at breakfast could mean approaching death by dinner. Governments scrambled to contain the disease — the state of Arizona outlawed handshakes and France made spitting a legal offence — but to little effect.1 On board the ship, many passengers wore masks throughout the voyage and avoided contact with others.

The ship’s manifest doesn’t record if anyone accompanied Idris, and there are no Halls or Hedleys listed on board. She may well have travelled alone. It is ironic that Margaret left her in Canada through the war, only to call her to England at the height of the most virulent illness the world had ever seen. According to those records, Idris was headed for Margate, Kent, to attend school, but this was never likely. As she wrote years later, “Mum had no desire to settle in England — she had become a colonial misfit among her own.”2

Idris arrived to the bustle and sooty air of Liverpool harbour on June 25. A day later, on the southeast coast of the country, she was reunited with an emotionally distant mother and a still playful, but bigger sister. Three years of separation had been, for all of them, a transformative time.

At first, Margaret was devastated and pined for the life she’d had with Bertie. But as the weeks passed her sadness turned to fancy, even consulting an astrologer to have her charts done. She came to believe it was possible that Bertie was not actually dead but only wounded or a prisoner of war or suffering from amnesia. Such things happened all the time. Without a body or even a personal effect to prove that he’d been killed, perhaps he was out there somewhere, smoking his pipe, twisting his moustache, waiting to be found.3 At the very least, she had to go to Belgium and see where he sup-posedly fell, to visit the grubby railway dugout where a small white cross marked his empty grave.

*

Idris arrived with her mother and sister at the Belgian town of Heyst-sur-Mer, or “Heist” as the locals called it. A summer holiday town, it was as relaxed as the towels that covered its wide sandy beaches. Postcards of the era show women in ankle-length skirts and children in striped bathing costumes frolicking in the surf or reading books under tipping umbrellas. But Margaret had not chosen Heist for its sand and surf. During the war, the town had been a German command post, a few miles from the terminus of the Western Front. This made it a convenient location from which to explore the fields where Herbert had fought.4 Margaret leased a four-level apartment that served as an annex to the Hotel des Bains, newly repaired after heavy German shelling destroyed much of the original façade. While Miki stayed with a nanny, Idris and Margaret spent two months taking day trips across northern Belgium, looking for Herbert. Nothing could have prepared them for the shattered landscape they encountered or for the mutilated veterans they found begging in the streets and train stations. As Idris would later recall, “Mum yet hoped for some miracle among shell-shocked drifting fugitive prisoners of war trudging westward, dazed, haggard, sometimes mindless.”5

Idris Hall (C) and Miki Hall (R) at the window of their apartments with unknown woman, Heist, Belgium, 1922.

Margaret’s fantasies might seem naïve, but the general public had only the vaguest ideas of what had happened during the war.6 The 1914 Defence of the Realm Act gave the British government sweeping powers to control citizen activities, especially regarding the communication of anything war related.7 For the duration of the conflict, virtually no stories indicating the true number of casualties or the horrors of battle were published in any newspaper in the British Dominion. It was feared that real images would shock the public and erode support for the war. The reality — the fields of rotting, mangled corpses, the undependable supply lines, the rat- and disease-infested trenches, the angry hopelessness of soldiers — was carefully guarded from entering the public imagination.8

Idris and younger sister Miki on the beach at Heist, Belgium, 1918.

A studio photograph of Margaret “Miki” Hall, age six, London, England, 1919.

By summer’s close, with no sign of Herbert, Margaret was again packing her daughters’ things into a large cedar-lined trunk. She and Herbert had talked about a “continental education” for the girls and this was her chance to fulfill that wish.9 The girls became boarders in the Catholic girls’ school Monastère des Bénèdictiones, Religieuses Françaises, two hours south of Heist in the town of Ooigem. Idris dreaded life in yet another boarding school, but at least this time Miki would be with her. The school was a collection of boxy, ivy-clad dormitories with orange tile roofs and a long, rectangular teaching hall, lined on one side by tall arched windows. In summer, the grounds could be beautiful, offering spacious green courtyards and the security of 20-foot-high brick walls. In winter months, however, the barren trees and dead grass made the grounds feel more like a cemetery.

From Margaret’s perspective, the school was ideal. A convent could offer all the opportunities of a secular boarding school, but at a much better price and with the possible added advantage of being strict enough to handle a tall twelve-year-old who enjoyed a good scrap and rolled her own cigarettes.

Idris (C, back row) and Miki (kneeling second from L, front row) in student class photo, Monastère des Bénèdictiones, Ooigem, Belgium, 1920.

Miki, the cherubic little girl who was as retiring as her sister was outgoing, settled in quickly. Photographs show a small, slightly plump girl with dark, bobbed hair and a round face. Everyone liked Miki, and it wasn’t long before she’d learned to “genuflect gracefully” and otherwise stay in the nuns’ good books.10 She learned French easily and was soon deemed ready for her First Communion. Idris’s experience was somewhat less positive.

Mine was a grudging progress, only belatedly acquired by din of Benedictine zeal. All innocent? Not I! Happily compliant? Not likely! Mother spoke of it as “a mind of her own” and did not deny me. I was promptly admonished with some acerbity, forbidden to shoot orchard apples with a slingshot, or to whistle. “Makes the Virgin Mary cry.” What a pity . . . . Problems faced in earlier schools began.11

The nuns labelled Idris uncorrectable, but that did not prevent her from gaining a degree of success and popularity.12 Idris noted the quiet rivalries that existed between the nuns and formed convenient allegiances. But there were genuine friendships too, most notably with the Mother Superior, Abbess Marie Pia, who recognized that Idris had her own kind of spirit. At the opposite end of the spectrum was Madame Headmistress, a “gross despot” who used her girth and booming voice to tyrannize students.13 Idris was one of the few who dared to defy “the Battle-Axe” and often suffered for it, though never with the severity visited upon the other girls. The nuns were only too aware of Idris’s close relationship with the Abbess (whom Idris referred to as “Mother of Leniency”) and measured their punishments. It could also be that Idris had discovered something that gave her a degree of power over her tormentors. She would later write, “In this rigid cloistered order, under vows of abstinence and chastity, only Headmistress was permitted to share her bedroom with another nun.”14

*

Idris turned thirteen that fall and, like Herbert, yearned for a life of adventure, not piety. Late at night, after the nuns had passed her door en route to their evening vigil, Idris lit a candle and lost herself in the contraband books she’d snuck into the convent after weekend visits with her mother: Kingston’s The Three Midshipmen, Conrad’s Java Sea tales, a stream of cheaply produced, serialized adventure tales for boys, and, of course, Silver Screen magazine.15

For Idris, the hair-raising adventure stories were inspirational. Before long, she was scrawling her own variations in a book she called her “fantasy journal.” There were tales of stormy sea adventures, of young girls overcoming despotic nuns, of true love threatened by blackmail, and of lovers separated by natural disasters and cruel parents. Whatever the crisis, there was always a swashbuckling heroine who bore an uncanny resemblance to Idris Hall. Idris shared her stories with some of the more wayward girls of the cloister. On free afternoons, during hikes along the gentle River Lys, Idris and friends would stop in the shade of ancient oaks to perform impromptu dramas based on her scripts.

*

At the school, both Idris and Miki contracted scabies. When Margaret heard of this, she promptly paid a visit to the headmistress, demanding that immediate measures be taken. Madame Headmistress coolly informed Margaret that, even in the presence of disease, the Benedictine Order did not take baths.16 There was a total prohibition on nudity: the girls could not even view their own bodies when changing. Bathing was never immersive, but done with a damp sponge under clothing.

This was not a complication that Margaret had anticipated. “You people,” she hissed, “must be the last holdouts for St. Jerome’s sanctimonious advice about female nudity. I’ll take cleanliness next to godliness!”17 She paid a quick visit to the Mother Superior and then to the convent’s patriarch priest, whom she plied with a five-star cognac. The next week two full-length zinc bathtubs were installed in the convent dormitories, for Miki’s and Idris’s exclusive use.

In the meantime, Margaret ensured her girls received proper medical attention. It was an experience Idris would never forget.

The cure became my first experience of standing totally nude before a man, a young Belgian physician. In the presence of my mother his gloved hands rubbed my body forcefully in every area with a stinking sulphur compound of Peruvian balsam seed benzoate. Standing head-level to him, anticipating every sensation, cringing inside . . . I stared wildly at Mum.18

*

Idris and Miki were permitted occasional trips to visit Margaret in Heist, where the trio spent lazy days wandering the wide beaches, collecting shells and stones, or visiting local cafés for treats of warm milk and petits fours. For Idris, though, half the adventure was getting to Heist. She no longer looked like a child and often attracted the attention of male passengers — a development that both frightened and fascinated her. Clattering rides north were spent keeping one eye on her sister while coolly pre-empting men’s attempts to engage her in conversation. It was no different at home in Heist, where she regularly endured “vulgar Continental annoyances.” Even the owner of the hotel was prone to holding Idris’s arm rather too intimately.19 When Margaret noticed, she counselled her daughter to employ what she called the Frigid British Stare. “If it’s an impudent look,” she said, “just give your eyes the cool dismissal. If the bottom pinch is too marked, just kick ’em in the shins, ’arry!”20

Margaret will have known all about the attentions of men, even now. Margaret was a panther among tabby cats: an independent woman from the new world, accustomed to handling her own affairs and quick to dispense with civilities when bored or affronted. Her strong, tempestuous character was put on public display when, during an afternoon stroll, Idris and Margaret witnessed a peasant brutally goading a tired horse with a hayfork, blood oozing where the prongs had pierced.21 Spewing an invective of incomprehensible Frenglish, Margaret charged the bewildered farmer, snatched his pitchfork, and walloped his backside with it. Amused onlookers cheered her on.

*

In early 1921 Margaret abruptly announced that she would return to Qualicum Beach to “see what could be retrieved of the family fortune.”22 She had finally accepted that her vigil in Belgium was futile; Bertie was gone. Back in British Columbia, however, Margaret had to face the fact that almost all the family’s commercial land holdings had been auctioned off to pay for property taxes and her Canadian friends and the families of the men Herbert had employed could not, or would not, offer the beleaguered widow assistance. Go home to England, they told her, and forget about Qualicum Beach.23

Idris, meanwhile, was chafing with boredom. The world beyond the cloisteral walls was churning with excitement while she missed it all. Even in sleepy Ooigem there had been a thrilling procession of Marxists through the town centre. Fearing a revolution, shopkeepers had shuttered their windows, and churches had locked their doors. The nuns sent the girls to chapel to chant the rosary and pray for safety. Idris, however, watched from a third-storey window while passionate young men with “Gregorian voices” boomed the “Internationale” and waved banners. She had little concept of what the Communists stood for, but she understood that change was at the heart of their message — and that was something she could believe in.

Then, in a way she couldn’t have predicted, change arrived of its own accord. During some routine snooping, the headmistress discovered and read one of Idris’s fantasy journals. Its tales of violence, monastery intrigue, and wild plans for escape scandalized the sisterhood. Even Mother Superior could not quell the shock and outrage that Idris’s lurid stories provoked among the nuns.

According to her later accounts, Idris was summoned to the headmistress’s office where she was excoriated for, as her journal would later say, “conceiving such irrational events.”24 The diary had been her best friend and to see it so sneeringly violated was unbearable. She lunged to retrieve it, but the headmistress yanked the book from reach. Before Idris could stop herself, a fist shot out and crashed into the nun’s mouth, sending her sprawling in a puddle of black and white fabric. Shrieking expletives, Idris kicked aside the sister’s fallen rosary and plucked her precious journal from the floor.25

It is impossible to know if this account has been embellished since we have only Idris’s word for it, but it is true that Margaret received a cable from the Mother Superior of the Monastère des Bénèdictiones, explaining the discovery of the journal and the necessary disclosure of its contents — after all, it contained the girl’s avowed intention to run away from school. The nuns, she wrote, could no longer cope. Idris was to be expelled from the cloister. Margaret hastily leased the remaining Vancouver Island properties for logging and ranching. Together with her war widow pension, the funds would meet life’s expenses with little left over for luxuries. At this point, according to her daughter, she hardly cared. She was tired of hauling her unhappiness from shore to shore. She “cabled a sailing date for the French Riviera, imploring, ‘Patience ’till we meet!’”26 For her part, Idris vowed to be “très sage.”

*

In late April 1921, the sisters, now fourteen and nine, dressed in tweed capes and took a train to Paris, where they boarded an express for the French Riviera. The train came to a stop in Nice, where Idris and Miki tumbled out onto the platform, wide-eyed at the soft air and warm sun. The girls soon spied their mother and ran into her outstretched arms.

A large black taxi delivered the reunited family to the Villa Marie-Thérèse, a rustic thick-walled villa built in the late 1600s. There were large fireplaces, deep-set windows with rippling glass, and heavy doors on every room. For the girls, though, their new home’s best feature was the elaborate private garden, overflowing with citrus fruits, roses, orchids, and mimosas. It was a stage for fantasy, transformed during the summer into Peter Pan and Wendy’s Neverland, and, in view of the garden’s fig trees, the Garden of Eden.

Well, there is something wrong with that story. I (had) no sooner strung large leaves fore and aft across Miki’s bare betweens, than she began to scream, dashed for the pump, tearing off the apron. The back of those leaves was worse than poison ivy! The Written Word lost some of its power for us.27

Though Idris was content to spend the summer naked in the garden, Margaret wanted to keep the girls more productively occupied. She enrolled them both in ballet classes at the Victoria Cinema Palace under Madame La Sédova, formerly of the Imperial Ballet, and in equestrian practice with a Cossack ex-cavalry officer who had recently fled the Bolshevik bloodbath. Miki, it turned out, had a knack for horses, while Idris excelled at dancing. She was soon dreaming of a career on the stage.

At summer’s close, the girls were registered in the tiny Raspini Pensionnat de Demoiselles on the Rue de France, No 107.28 It was another convent school, run by two “gaunt as parchment”29 nuns. Idris steeled herself for another spell of regimented boredom, but consoled herself that at least this time she could spend weekends at home with her mother.

When school began, Idris was pleasantly surprised. In contrast to the banal uniformity of the Monastère des Bénèdictiones, students at the Raspini were ethnically diverse and culturally sophisticated. The school was also less strict than the Belgian cloister had been, with the unstated aim of “finishing” privileged girls in preparation for a successful marriage rather than a life of abstinent piety. In her journals, Idris noted a blond, olive-skinned Corsican, a “sultry” Romanian violinist who made her classmates swoon to Godard’s Berceuse de Jocelyn, several hot-tempered Italians, and above all, an American girl of uncertain ethnicity. Like Idris, Eliza was tall, outgoing, and looked older than her years.30 She introduced Idris to make-up, pedicures, ballroom dancing, wine, and urbane literature, especially the work of Madame de Staël. Eliza’s mother was a poet and a friend of the French writer, Colette. In later life, Idris wondered if Eliza was the model for Colette’s famous would-be courtesan in Gigi.31

*

No high walls surrounded the Raspini school, and students were afforded relative freedom, but Idris enjoyed more than most. She was given her own room and was permitted to leave the school on weekends to run errands for her mother, now less than an hour south by tram. It was a liberty Idris cherished and sometimes abused. Occasionally, on early evening trips home from a matinee or shopping at the Place Masséna, Idris would pass by the local bordello. “They were corpulent, painted — wore wigs, I thought. If daytime, we smiled at them and they smiled. Raspini girls recognized them all by sight but remained strictly aloof.” Margaret said she felt terribly sorry for these women, and Idris was shocked to learn that the girls there were legally and forcibly inspected for syphilis. Yet she was fascinated by them. “There was something about their mien,” she wrote. “Something about the way they walked.”32

Now fifteen, Idris was increasingly interested in fashion and conscious of the changes that time and ballet were effecting in her body. Margaret noticed the changes too, telling her that her shape “would never be better.”33 When a Côte d’Azur beauty contest was announced, Idris begged her mother to allow her to enter. The first prize was a picture contract with a well-known French company.34 In the end, Idris didn’t win, but the experience of being fawned over and admired whet her appetite.

Mother Superior, Miki, and Idris, age fifteen, at the Raspini Pensionnat de Demoiselles, Nice, France, 1922.

*

Idris was happier in the South of France than she had been in Belgium but still resented the drudgery of classes, homework, and school rules. Like Herbert before her, she longed for excitement and adventure. Then, in the spring of 1922, while on one of her many sorties from downtown Nice to the Villa Marie-Thérèse, she paused at the local aerodrome to watch the planes crisscross the tiny airfield and twist through the Mediterranean sky.35 She imagined herself in the cockpit, with goggles and scarf, climbing through the air, soaring over great distances.

And while Idris watched the planes, the pilots began watching her. Soon a handsome war hero named Marc Maicon36 strolled over and introduced himself. They chatted for a while and he offered to give Idris and her groceries a ride home — not in his Caudron G.3 airplane, but in his cherry red Peugeot sports car. She took one look at his wavy brown hair and big brown eyes and handed her groceries to Maicon.

By the time school recessed for the summer, rides home from the aerodrome were regular occurrences. With Margaret’s approval, Marc began teaching Idris how to drive. Naturally, Idris was soon infatuated. “Had (mum) been aware of my immediate captivation, things would have been quite different.”37 But it wasn’t just Marc that Idris was falling for. She loved the speed and mobility of driving. This was independence — and it didn’t hurt that these wheels came complete with a dashing owner. “I was to remember how the confines of a car, its reassuring purr and motion, breeds an extraordinary sense of isolation, intimacy . . . privacy.”38

Even if Margaret fancied that Idris might make herself a good catch with the war hero pilot, she likely had little sense of how rapidly things were really progressing. Idris’s journal recorded how with each meeting the caresses grew more insistent, the romantic talk more serious. During one lesson, as he leaned across Idris to help her steer, he proposed they find some place to be alone. Idris declined at first but eventually “agreed to go with him to a small villa near the aerodrome.”39 They drove to an out-of-the-way house where a plump matron showed them to a small room on the upper floor. After some initial awkwardness, he manoeuvred Idris to the single bed and began unbuttoning her shirt. He praised her smooth skin, her nascent curves, and blossoming breasts. “You should be wearing a soutien gorge,” he told her, “or those little tetons will begin to droop.” As he ran his fingers over her, Idris, not exactly sure what they were doing, began to giggle un-controllably.

Perplexed, Marc asked if it was her first time. “No, of course not,” she lied. But the giggles would not stop. Fearing the moment would be lost, Marc leaned over and kissed her. Although she was still in her skirts, he lay on top of her, pressing her legs apart. His motions had the desired effect. Perhaps surprised by these new sensations, her laughter trailed away. But soon, too, did l’aviateur. His pleasant movements ceased completely.

To Idris’s great shock, he seemed to be crying. He lifted his head. “Excuse-moi, cherie. J’ai . . . j’ai réjoui sans toi.” Idris hadn’t the slightest idea what he meant. “He has rejoiced without me?"40

*

In the fall, Idris and Miki returned to the Raspini where, as usual, Miki flourished and Idris chafed. In her journal, Idris describes being “tortured by strange yearnings” and frustrated that she and her mother could not “speak the same language.” Compounding matters, her friend (and co-troublemaker) Eliza had not returned to school from Paris. After the excitement of summer, school felt lonely and restrictive. Idris wanted something exciting to happen, but there was, she believed, nothing to look forward to.

Shortly after Idris’s sixteenth birthday, she was in her room at the Raspini, gazing through her window at the wide and inviting Mediterranean. White masts dotted the waters, a hundred specks, each connected to some ship, moving towards some glowing adventure she was not a part of. Depressed, she flopped on her bed and began leafing through Le Petit Niçois newspaper until an unusual article caught her eye: a “quixotic American, racing an automobile around the world” had arrived in Nice. According to the article, the Wanderwell Expedition was making movies of its travels and would be screening them the following evening at the Victoria Palace.41 An accompanying photograph showed the handsome expedition leader, Captain Wanderwell, wearing a kind of military uniform and leaning nonchalantly against a racy, fenderless, doorless roadster. Idris was intoxicated. The question was not whether she should sneak into town to see the show, but how.

The solution proved easy enough. “I had no conscience about cutting school — just advised La Directrice that Maman requested my absence. Then . . . I was out on the street, alone . . . at dusk.”42 She made her way to the Victoria Palace theatre and used her smile and swagger on an admiring doorman to let her in without paying.

In the crowded lobby, Idris studied photographs highlighting the ex-pedition’s adventures: American president Harding autographing the hood of the car, General Pershing shaking hands with Captain Wanderwell, a car dashing through Mississippi floods, the Prince of Wales saluting Wanderwell’s crew, which included, Idris noted, two females. The captain himself looked to be in his late twenties, blond, lean but muscular, with a square jaw and smiling eyes that expressed confidence and amusement. His uniform consisted of gabardine jodhpurs, black Pershing boots, and a jaunty field service cap.43 In no picture was anyone ever out of uniform.

A staged photo op of Walter with two unidentified girls in his party, London, England, October 1922. This was just prior to travelling to the South of France and meeting sixteen-year-old Idris Hall.

For almost an hour, “speaking in broad Yankee twang . . . sparked here and there with French words,” Captain Wanderwell treated his audience to the towering redwoods of California, the deserts of Mexico (including a visit with revolutionary Pancho Villa), the Florida Everglades, the engineering miracles of New York City, as well as scenes from Cuba, South Africa, South America, Scotland, and England before concluding with images of Paris filmed only days before.44 At that time, perhaps only Burton Holmes could offer audiences such a feast of world vistas.45

Idris was gobsmacked. Here, in the flesh, was a man living a life more adventurous than anything she had dared dream in her journals. After the show she snuck backstage, only to find that others had the same idea. “A line of fans already waited for the privilege of shaking hands with this young daredevil.” She pushed her way to the front of the queue but, “His dazzling smile overwhelmed me and I could only stammer, ‘My felicitations.’ ‘Ah, you speak English’, he said. ‘Great — come along.’”46

In the company of other fans, she followed the captain outside. There he signed autographs and answered questions about the aims of his expedition. He was, he said, engaged in a race around the world with another car. The goal was to see as many countries as possible before the next World’s Fair, scheduled to be in Chicago in three years’ time.47 The race had been nicknamed the “Million Dollar Wager” because the winner would be awarded all films, photographs, and other memorabilia from both teams, as well as, it was said, all rights to their use, the value of which would approach seven figures.

When he turned to sign Idris’s souvenir pamphlet, Wanderwell seemed to recall why he had invited her along. He snatched a newspaper from a nearby crew member and flipped to an interior page. He pointed to an ad at the top. “Right now, I’m looking for an interpreter,” he began, “and somebody who can act or sing.” Idris was momentarily stumped but then told him that she could dance, if that was any help. He smiled. She was invited to visit his hotel the next morning, the Normandie.

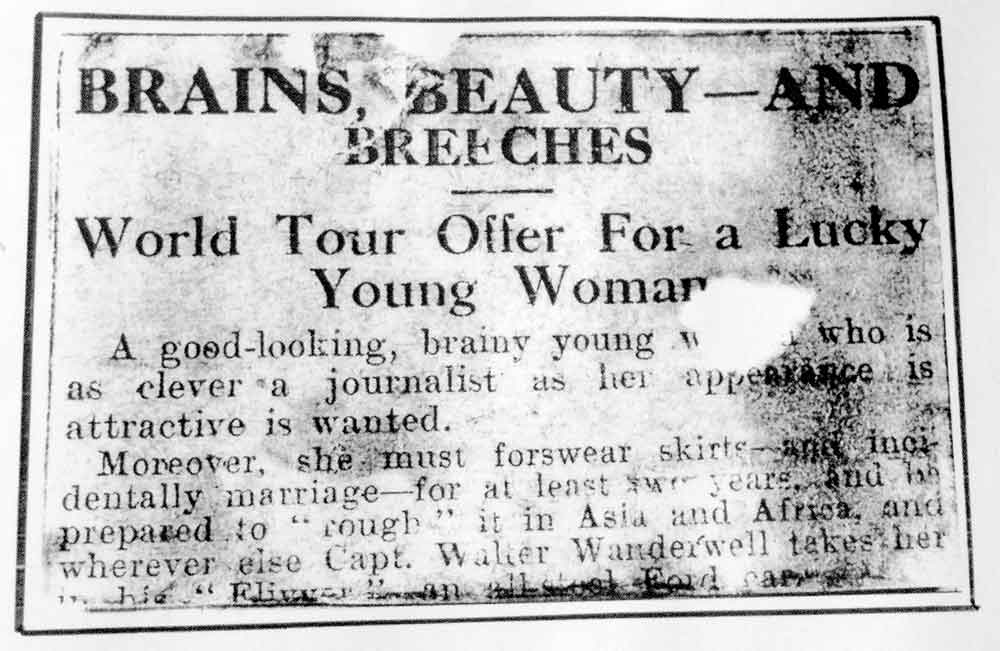

The original newspaper clipping that started it all. From the English-language Paris Herald, Walter Wanderwell seeks a young woman to join the Wanderwell Expedition, December 1922.

*

Idris walked back to the school, transfixed by the newspaper that Captain Wanderwell had given her.

World tour offer for lucky young woman

Captain Walter Wanderwell is seeking a lady secretary to join his world tour by auto. . . . A good-looking, brainy young person, who is as clever a journalist as her appearance is attractive. She must forswear skirts, and incidentally marriage, for at least two years. Be prepared to rough it in Asia and Africa, to record the adventures of the party, to learn to work before and behind a movie camera.48

This was everything she’d ever dreamed of. She imagined herself in the Wanderwell uniform, lecturing audiences, earning money and applause. Then, like cold water down her back, she imagined her mother. Somehow she had to make her mother see that further schooling was pointless. Somehow she had to convince her that she was ready to join an expedition that aimed to traverse, often for the first time, some of the most forbidding lands on the planet.