A full chapter is devoted to Pilates, as it has become a popular and successful conditioning program. If teaching is done correctly, a certified Pilates instructor can effectively lead a person or class through a workout with attention paid to injury prevention, correct body placement, and focused muscle work. The psoas is very involved, sometimes to a fault. The instructor must cue the student properly, explaining the neutral spinal curves and not forcing the flattening of the lower back into the surface. Using “naval to spine” is only an image that helps engage the abdominals and psoas to fall toward the spine, then lengthen; compression is not the goal. If the core is forced into its depths, there will be no freedom of movement. It takes practice to find the necessary quality of motion that allows flow without restriction. It is a lifelong process.

Why Pilates?

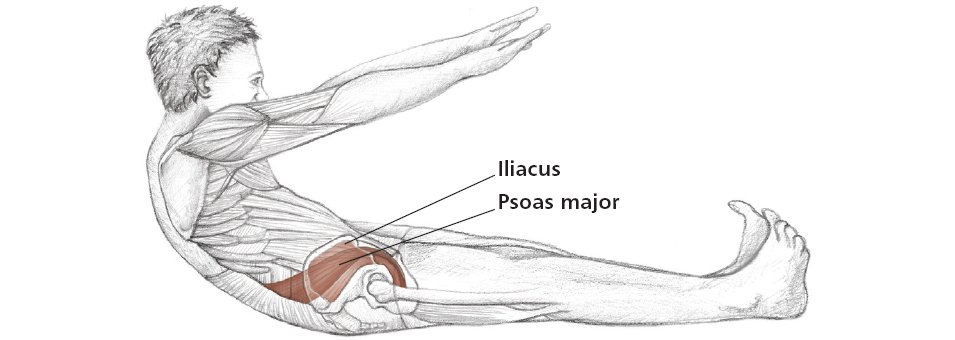

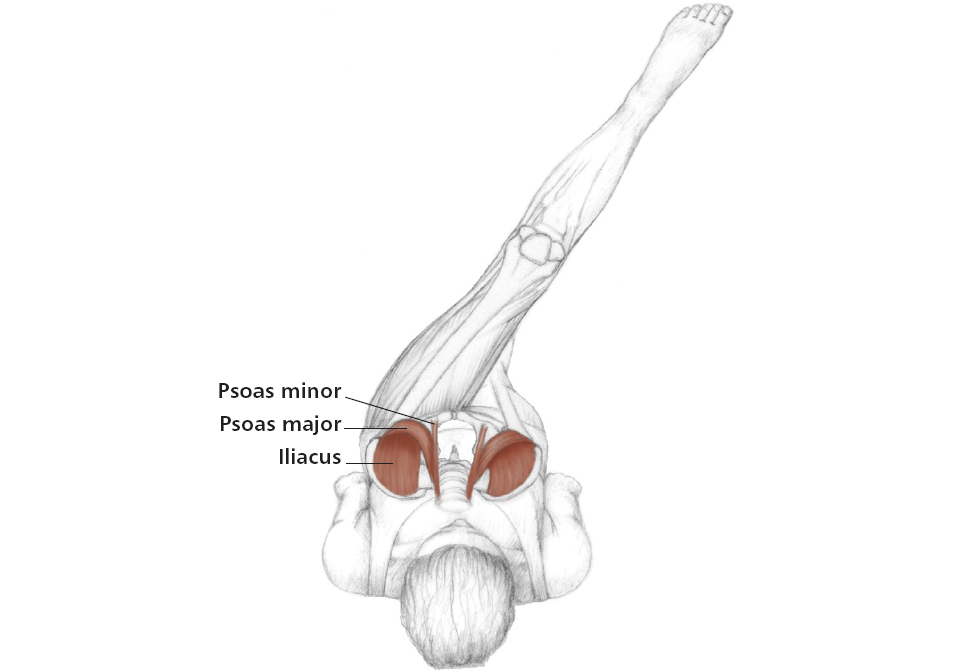

A Pilates workout is based on concepts of body alignment (in general posture as well as during the exercises), muscle balance or lack thereof, strength, and flexibility: all areas the psoas is a component of, depending on the movement. This section will concentrate on the mechanical role of the psoas in relation to specific “classical” Pilates mat exercises.

Almost all Pilates work includes hip and spinal flexion/extension, which the psoas can be part of, not solely, but integrally. It is known as a hip flexor because it is connected with the iliopsoas muscle group, and has a lumbar spine attachment, where its role is still debated. But the psoas is mostly involved in Pilates work because of its link from the upper to the lower extremity. This makes it a central core muscle along with the abdominals, quadratus lumborum, and other spinal extensors; but it is the only one to connect to the leg. In all exercises these muscles must help each other do their jobs in relation to body movement and positioning. If the psoas has to be the only stabilizer, it will not be released enough to be receptive. When the pelvis is stable, the psoas can go about its “business.”

Pilates is an excellent workout program, with minimal drawbacks: biomechanically, there is a lot of hip flexion, and not as much stretch as most people believe. However, there is “length” presented in every exercise, which can compensate for this. There is also the possibility of too much core work. Overworked muscles tend to be tight, and the core needs to breathe.

Cueing the breath is essential in every exercise, as well as knowing the basic principles of mind/muscle control, a stable center, balanced flow, kinesthetic awareness, and moving without tension. Muscle endurance as well as strength is optimized when one does Pilates correctly, with precision and commitment. Find a Pilates instructor who understands this approach and has in-depth knowledge of the human body, without forcing the body into injury.

The Classical Beginner Pilates Mat Routine: Moving without Tension

Listed in order of presentation during a class, the following exercises indicate psoas work. Keep in mind, most Pilates floor exercises (except the Hundred) are repeated five or six times, with slower, controlled motion the emphasis.

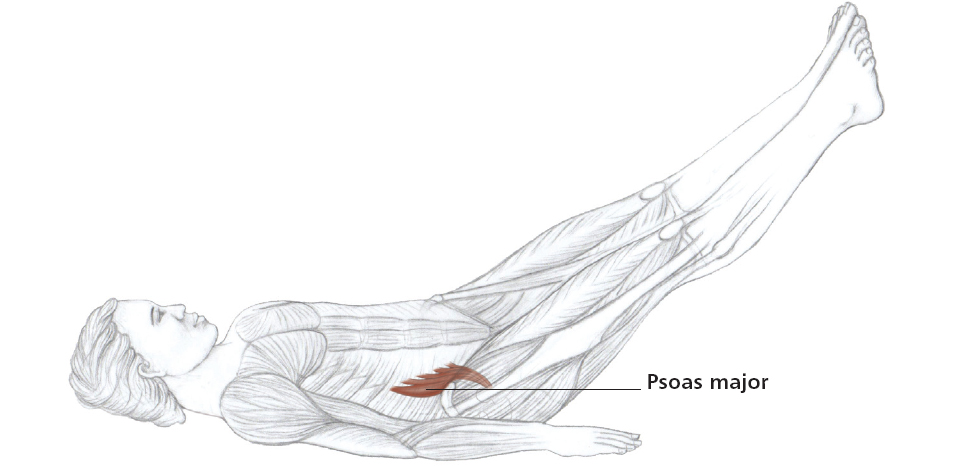

1.The Hundred: The psoas is strengthened minimally as both a hip and lumbar spine flexor, and a lower spine extensor, so it is one of the muscles engaged in this exercise. When the legs are straight, at a 90-degree angle, and the pelvis is fixed, the psoas helps stabilize the spine as well as work secondarily with the iliacus as the legs lower to 45 degrees. During the exercise the psoas also flexes the upper lumbar spine, along with the abdominals, and stabilizes the flexed position while the arms beat 100 times. Care should be taken not to flex the lower lumbar region, as the spine remains neutral.

The Hundred can begin as a Level I exercise if the knees are bent, and then be increased to the Level II version explained above (legs at 45 degrees).

Technique: Lie on back, then flex the spine with the feet either on or off the floor, knees bent (legs straight and/or lowered is more advanced); the position is held, and the “100” is how many times the arms pump (arms are held straight in at the sides of the body). This position also strengthens the anterior neck muscles.

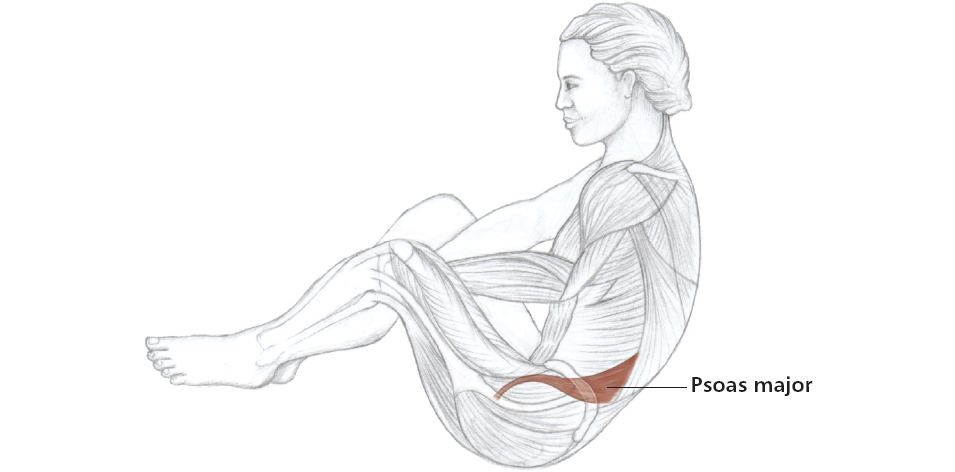

Figure 4.1: The Pilates Hundred, Level II.

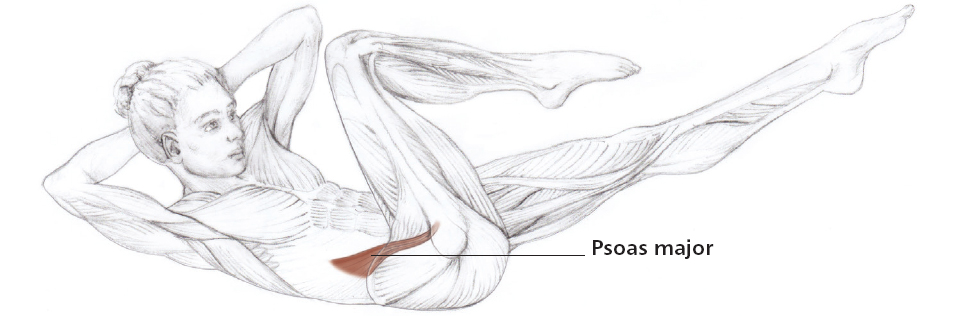

2.The Roll-Up: Another good psoas worker, the Roll-Up causes the psoas to contract harder during the second half of the exercise, when the abdominals begin to work less against gravity as the body lifts into more hip and spine flexion. There is a moment when the psoas sits back against the spine as it responds to the movement.

The Roll-Up is usually done at the beginning of a basic Pilates class, but after teaching for many years, this author feels a straight leg Roll-Up with arms reaching toward the front is actually an intermediate movement for many people. Begin with the knees bent, heels on the floor, and hands connected to the floor to aid the lower back and increase muscle awareness by allowing both sides of the body (and psoas!) to work equally as one rolls up. The roll back down is just as important.

If this is too easy and the back responds well, then the regular Roll-Up can be done with straight legs.

The illustration shows Level II, which can be accomplished only if the abdominals, psoas, and integral muscles are strong enough.

Figure 4.2: The Roll-Up, Level II. Press shoulders down and back as the arms reach forward.

Given that the psoas muscles are responsible for so much, they can actually become overworked and too fatigued. The most important concept to remember is that the psoas needs to function correctly in all its roles, without limiting it to strength and tightness.

3.Single Leg Circles: This one is interesting from a psoas point of view. The spine is stabilized by the spinal extensors, abdominal engagement, and the floor. The psoas helps at the lumbar area. The upper leg, at 90 degrees, circles across, down, out, and up, completing the actions of hip adduction, extension, abduction, and flexion (this equals circumduction); rotation can also be added. The psoas major acts as a minimal mover at the hip joint as part of the iliopsoas muscle group, and stabilizes the spine.

Figure 4.3: Single Leg Circles.

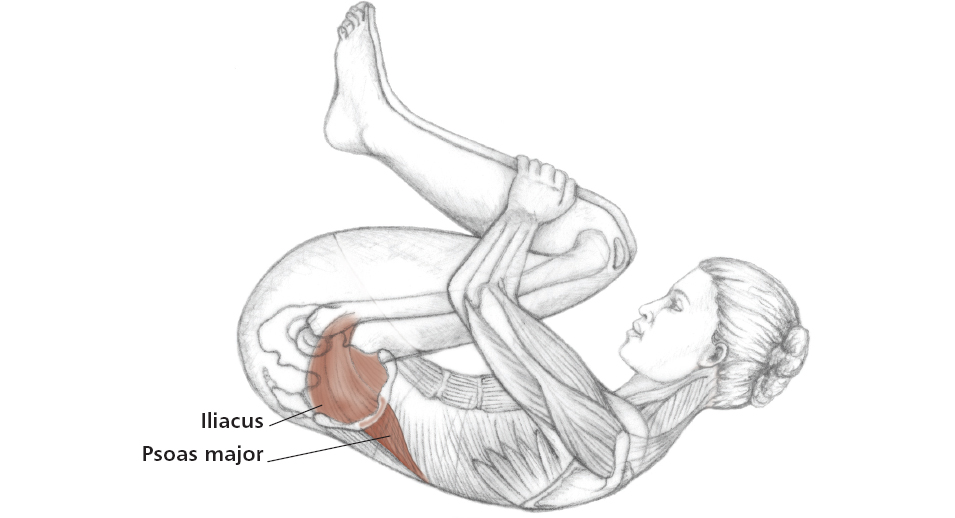

4.Rolling like a Ball: Using a complete hip and spine flexion position, the focus of this exercise is control of the position as one rolls through the lower to mid spine on the mat. Though fun to do, some spines are just too bony or injured to be rolled on, so use caution if it is uncomfortable. The psoas works as a stabilizer, especially when balancing just behind the sit bones. The work increases on the way up from the roll to a balanced position.

Figure 4.4: Rolling like a Ball.

The next five (5 to 9) exercises are called the abdominal series. Each exercise is done 5–8 times, with even flow throughout the repetitions.

5.Single Leg Stretch: The psoas will work as a weak hip and partial spine flexor, but mostly engages as it is challenged when switching from one leg to the other. This is a Level I exercise, where concentration is on the core; hip work is secondary.

Figure 4.5: Single Leg Stretch.

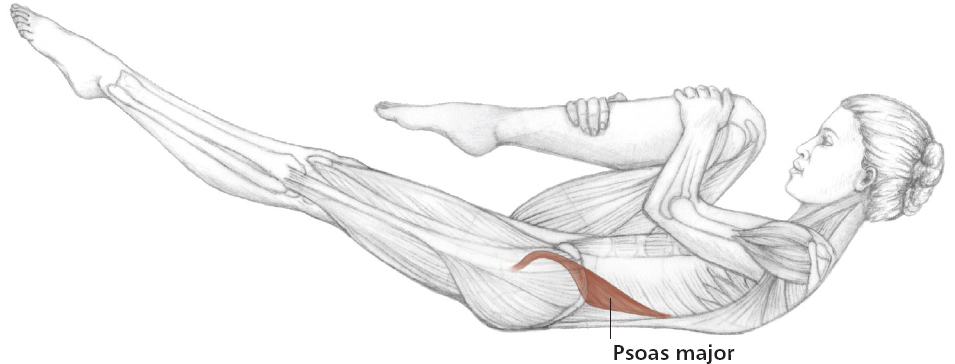

6.Double Leg Stretch: This exercise is a more difficult version of the Single Leg Stretch, as both legs are extended away from the body at the same time, without use of the arms. This advanced leverage system makes the psoas work hard as a connector while the abdominals stabilize. It is a difficult exercise if the abdominals and psoas are weak.

Figure 4.6: Double Leg Stretch.

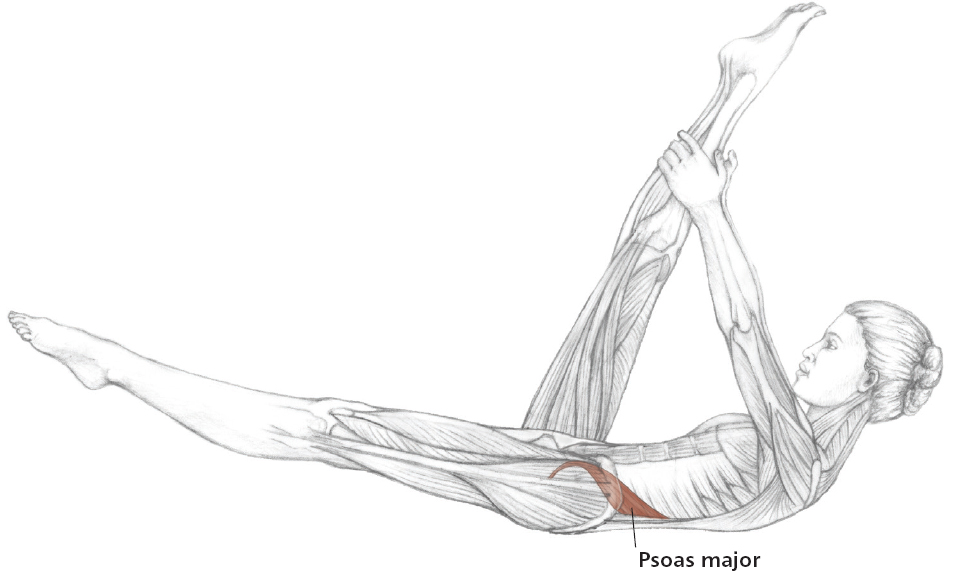

7.Scissors: This is useful as a hamstring stretch, but the psoas is also engaged to a small degree in both flexion and stabilization of the hip and spine as one switches the legs. Releasing the arms forward instead of holding the leg will increase the challenge of the exercise.

Figure 4.7: Scissors.

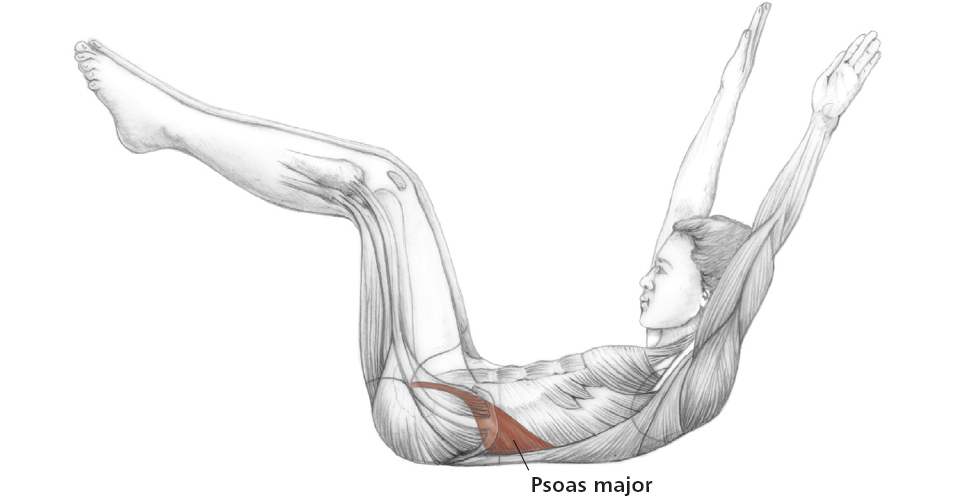

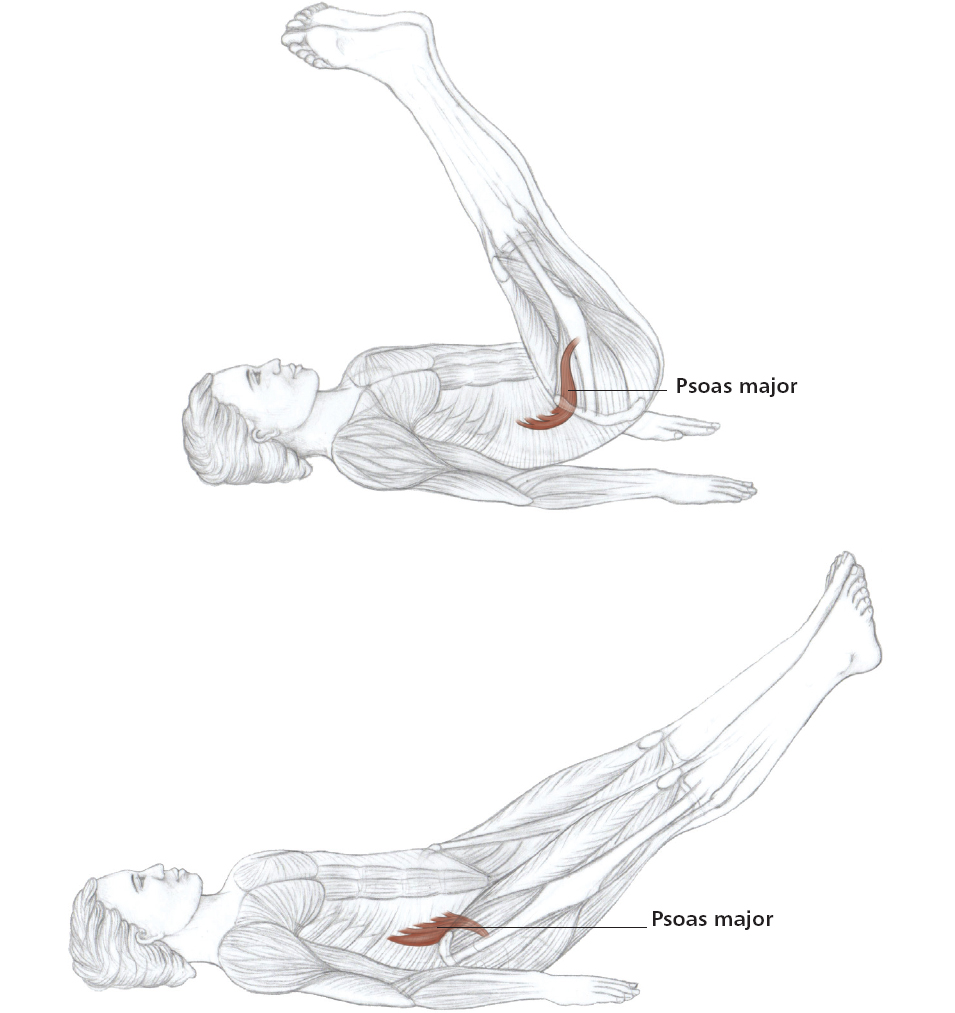

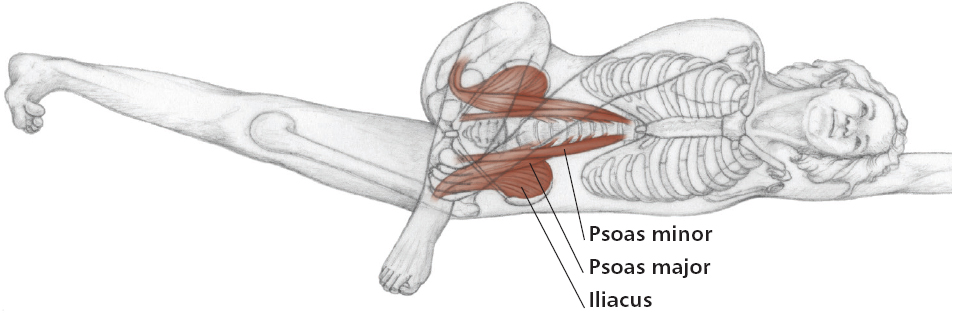

8.Leg Lowers: The name describes the movement. Lowering the legs from a 90-degree position works the psoas as a stabilizer of the lumbar spine, and raising the legs back up contracts the entire iliopsoas muscle group as well as other hip flexors; working against gravity with the weight of both legs is not easy to do. To aid the lower back, bend the knees slightly as a Level I exercise, and cushion the sacral area with the hands underneath. Try to keep the spine neutral. The head and arms can be raised off the floor for added resistance.

Figure 4.8: Leg Lowers.

9.Crisscross: This is another psoas worker, but focuses more on the oblique abdominal muscles. The psoas acts as a stabilizer of the lower spine and as a flexor of the hip, although minimal. It will engage as a deep core muscle while the person switches from one side to the other. Do not pull on the neck with the hands; lightly touch the back of the cervical area with the elbows out, not in.

Figure 4.9: Crisscross.

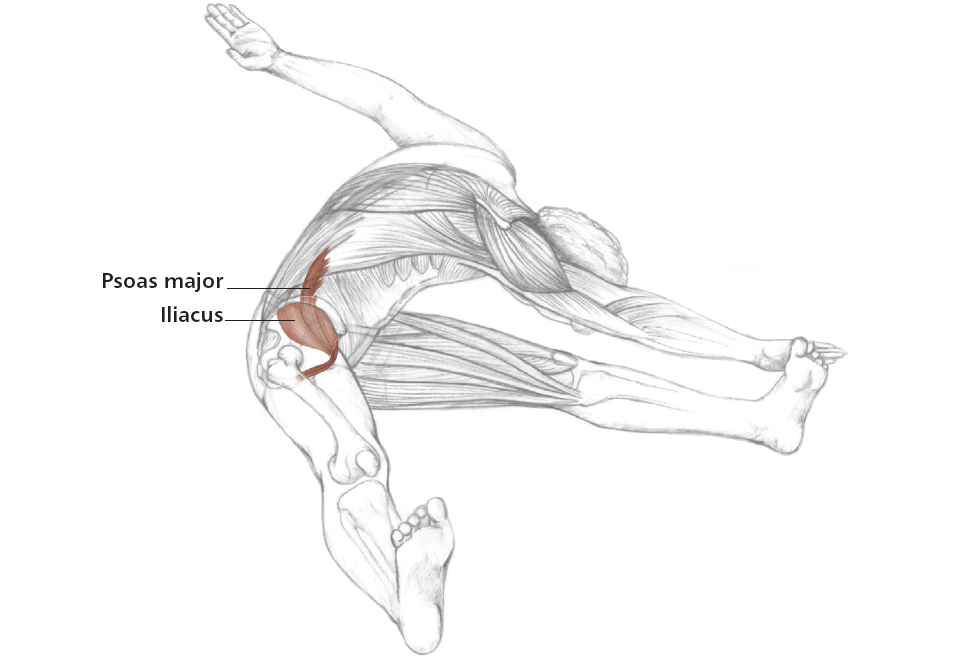

10. Spine Stretch: In the Spine Stretch there is hip and spinal flexion, which can activate the psoas, but the spine extends against gravity in the second half of the exercise back to the vertical position. The psoas will mostly engage along with the transversospinalis muscle group to support extension of the spine on the way up from the flexed position. Sitting with the back against a wall will aid in awareness; keep the shoulders down as the spine extends.

Figure 4.10: Spine Stretch.

Notice up to this point there has not been much stretch indicated for the psoas area and one is almost halfway through a classical Pilates mat class. This author would do the following stretch at this point.

Figure 4.11: Purvottonasana (Upward Plank Pose).

11. Corkscrew: The psoas is a main worker throughout this exercise, as a stabilizer at some positions and as a mover at others. A difficult exercise for most people, it involves circling the legs together as the head, spine, and pelvis remain stable on the floor. If possible, the hips can lift at the end of a circle, engaging not only the psoas but also the deep pelvic muscles. The Kegel move (Chapter 2), which is a “squeeze” of the sit bones toward each other, can be done here if the hips are lifted at the end.

Taking the legs below 45 degrees toward the floor is not advised, and placing the hands under the sacrum will aid the lower back.

Figure 4.12: Corkscrew.

12. The Saw: This is similar to the spine stretch, with rotation of the spine added, where the psoas works great as a stabilizer and extensor of the lumbar spine against gravity. This is one of the most specific exercises in the Pilates system, where full attention must be paid to alignment, positioning, and core control of the entire movement; it is not about reaching the toes.

Figure 4.13: The Saw.

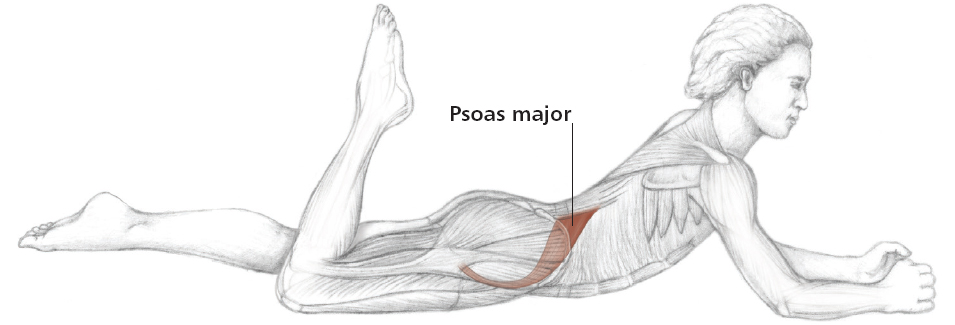

13. Swan Prep: Finally a psoas stretcher! The first half of this exercise emphasizes the raising of the upper extremity while the lower half remains on the floor. This will elongate the front of the hip where the psoas is located distally. The psoas also helps stabilize the lower spine.

The second part of the exercise is to raise the lower extremity while the upper half remains on the floor, which also stretches the psoas at the front of the hip. Its supporting action at the lumbar spine is working as well.

Figure 4.14: Swan Prep.

14. Single Leg Kicks: The psoas is slightly stretching at the front of the hip as one lies prone, propped up on the elbows, while the knees alternately bend. The core muscles, especially the abdominals and upper psoas, support the lower spine when engaged.

Figure 4.15: Single Leg Kicks.

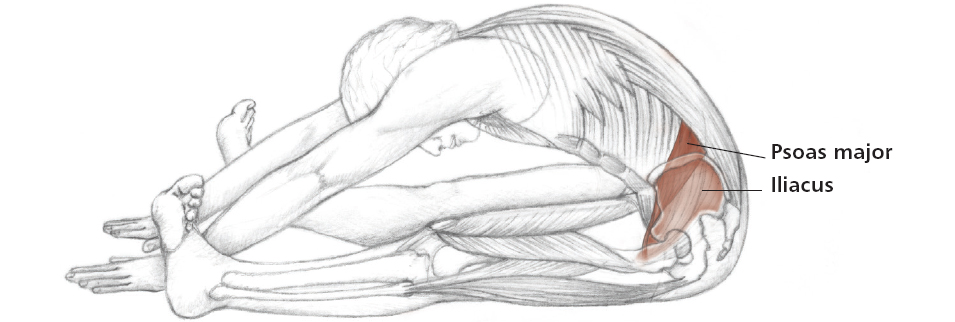

15. Child’s Pose: One of the few resting poses in the Pilates beginner mat class, it stretches the lower spine by elongation of the muscles, which includes the upper portion of the psoas. It is a released position.

Figure 4.16: Child’s Pose.

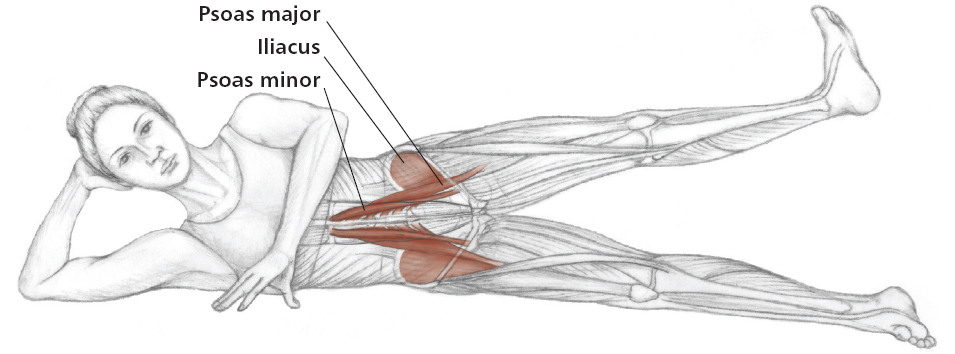

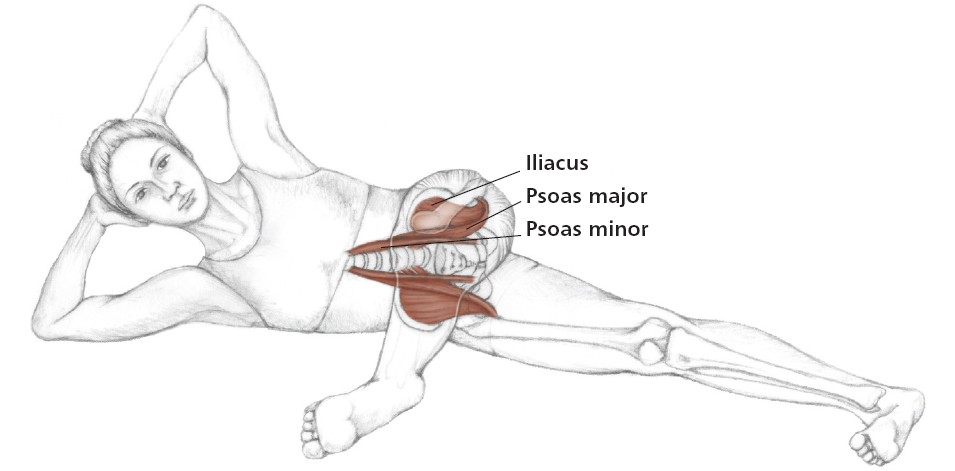

The psoas major helps with core stabilization in the following exercises. The arm position for any side-lying exercise is: Level I, head rests on outstretched bottom arm with top hand in front of chest; Level II: Lift torso and rest on bottom forearm extended in front, or as shown in Figure 4.17; Level III is shown in Figure 4.18. Five leg repetitions are usually done slowly in each exercise.

16. Side Leg Lifts: This exercise focuses on actions at the hip joint that the psoas is not active in, such as abduction and adduction. If the leg is externally rotated, it might incorporate the psoas to a small extent, for example as shown in the illustration below. Add circling the leg for more challenge and work.

Figure 4.17: Side Leg Lifts.

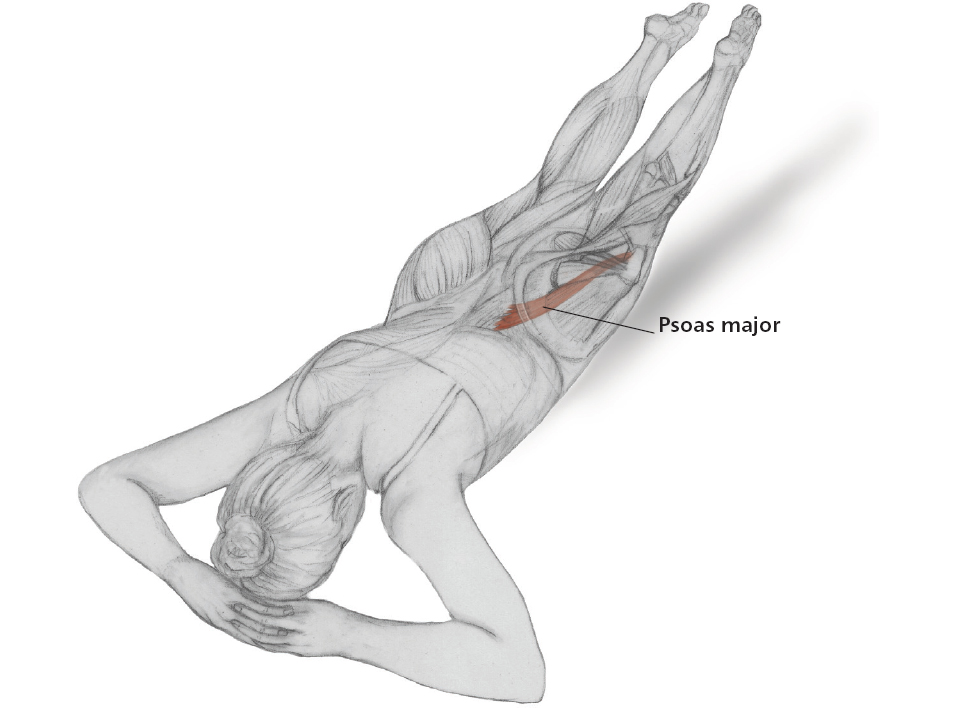

17. Side Leg Kicks: This one is great for the psoas, as it works to keep the torso stable, while helping as a hip flexor. While lying on the side, the top leg kicks forward twice (hip flexion), then lengthens to the back, extending the hip. This last action stretches the psoas.

Figure 4.18: Side Leg Kicks.

18. Bottom Leg Lifts: With emphasis on the bottom leg lifting up against gravity, the hip adductors are strengthened. The psoas works more as a stabilizer during spinal extension.

Figure 4.19: Bottom Leg Lifts.

Stretches: Two stretches that could be done here are the Half-Bridge Stretch (for the front hip flexors such as the iliopsoas) and the Crossed-Leg Stretch, overleaf, (for external hip rotators, gluteals and ITB, and lower spine extensors).

Figure 4.20: Half-Bridge Stretch.

Crossed-Leg Stretch: Another classic stretch is the Crossed-Leg Stretch. Lie on the back, cross the ankle of the worked leg over the other knee, and pull the bottom thigh to the chest with both hands.

Figure 4.21: Crossed-Leg Stretch.

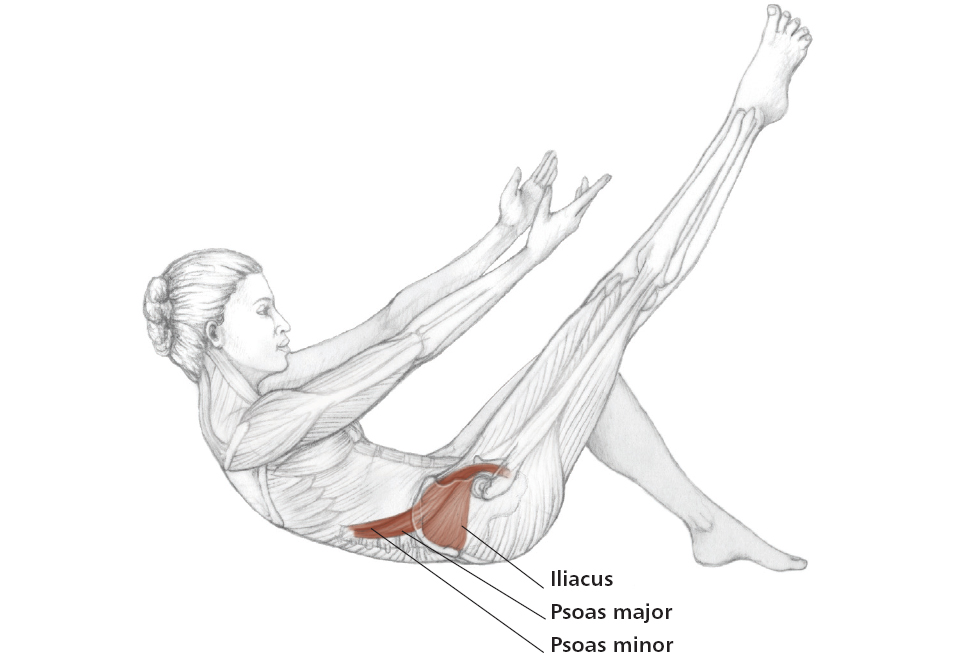

19. The Half-Teaser: Since this is a beginner mat routine list, the regular teaser is usually too difficult for novices. In Level I, do not extend both legs while lying on the floor – just one, raised to knee height; keep the other leg bent, with the foot out on the floor. Squeeze the thighs together as you roll up and down, slowly and with control. Switch legs after 3 repetitions.

This exercise is a psoas worker on the straight leg side, and stabilizer on the bent knee side.

Figure 4.22: The Half-Teaser.

20. The Seal: From a sitting position, the hips are flexed as well as the spine, with the hands holding the outside of the ankles, and the knees out to the sides, with the heels pulled in. The psoas will act as a stabilizer and core muscle throughout most of the exercise. Roll back and up through the spine three times, clapping the feet for fun at the top and bottom of the rolls. (Similar to 4. Rolling like a Ball on page 58, with outward hip rotation incorporated.)

Figure 4.23: The Seal.

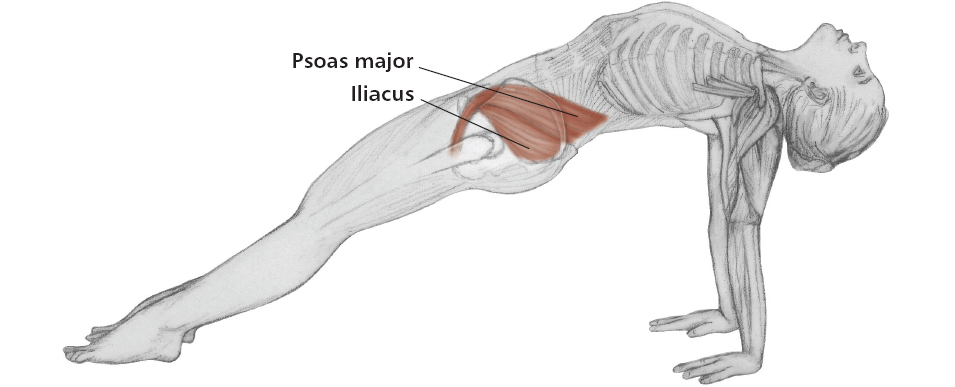

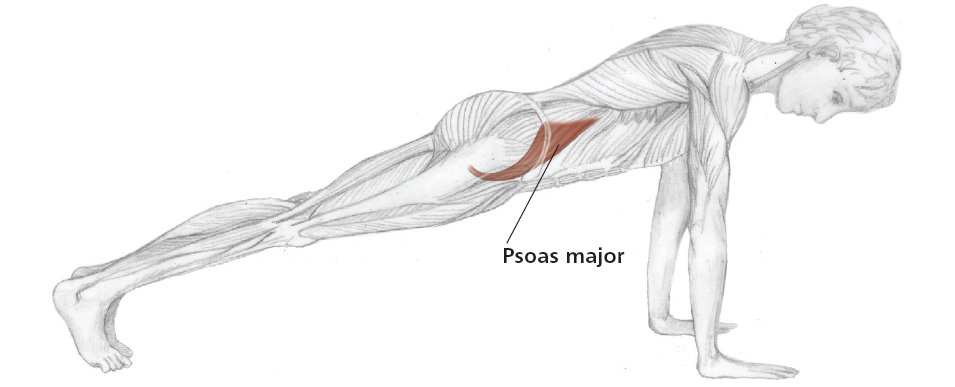

21. The End: From a standing position, roll down to the floor with the knees slightly bent, walk out on the hands, and assume a front support position. Push-ups can be added. Walk hands back to feet while engaging the core and trying not to bobble. Roll back up. The psoas helps stabilize the core throughout.

Figure 4.24: The End.

To reiterate, the psoas can only maintain a healthy response if other core muscles are engaged properly. Too much stress during repetitive exercise will result in imbalance and exhaustion.

A Note about Pilates Equipment

Pilates Machines

The machines used in a Pilates workout can range from the Reformer only, to others such as the Wunda and High Chairs, the Trapeze, the Cadillac, the Ladder and Hump Barrels, the Pilates Stick, the Tower, and more. A fully trained Pilates personal instructor is essential as a guide while one completes a full routine. This is an intense, concentrated workout that incorporates the psoas as both a stabilizer and a mover in most exercises. Care must be taken, as in the Pilates mat class, to focus on correct muscular effort so the psoas is not overworked.

Other Equipment

The use of Pilates rings, bands, balls, blades, ropes, rollers, ped-o-pulls, and so on are advantageous because resistance is added to challenge the workout. Original physical integrity learned in a basic mat class, and maintained, can aid anyone when equipment is added.

This author suggests that Pilates work is effective, but not in and of itself.

A routine of Pilates conditioning, along with yoga and walking or swimming, or even light weight training, is a great way to achieve a balance without sensitive body mechanisms being disrupted by added force or impact.