Palliative medicine and symptom control

Miriam J Johnson, Gail E Eva, Sara Booth

Introduction and General Aspects

Palliative care is the active total care of patients who have advanced, progressive, life-shortening disease. It should be based on needs and not diagnosis, and is required in non-malignant diseases as well as in cancer (Box 3.1).

The goal of palliative care is to achieve the best possible quality of life for patients and their carers by:

• managing physical, psychological, social and spiritual problems so as to provide excellent symptom control

• enabling patients to be cared for and to die in the place of their choice

• enabling the acceptance of death as a normal process when life-prolonging treatments no longer improve or maintain quality of life

• providing the opportunity to say goodbye and bring closure.

Who provides palliative care?

A hallmark of palliative care is the multiprofessional team, as single professionals cannot provide the breadth of necessary expertise. The emotional demands of working in this area require team support to enable balanced, compassionate and professional care.

All healthcare providers should have basic palliative care skills and access to a specialist palliative care (SPC) team. They should be aware of the services that the local SPC teams can offer and recognize when referral is appropriate. A problem-based approach to disease management will ensure that patients and carers obtain access to appropriate support services, including SPC, and will avoid an either/or approach (‘either curative treatment or palliative care’).

Good communication between members of the healthcare team, and between patient and carer, underpins the successful management of advanced disease and end-of-life care. Effective liaison between the hospital, primary care and hospice is also essential.

When should palliative care needs be assessed – problems rather than prognosis?

Early assessment of needs, with SPC referral if required, is crucial to achieving the best outcome for rehabilitation and for maintaining or improving quality of life for both patient and carer. Palliative care is most effective when it is included as part of routine care as soon as possible after diagnosis, alongside disease-specific therapy, such as radio/chemotherapy for cancer or cardiac medication for heart failure. Early referral links palliative care with quality-of-life improvements; positive associations increase the likelihood that patients and families continue to use palliative care services when they need them over the course of the illness. In cancer, there is good evidence that integrating palliative care and anti-tumour treatment soon after diagnosis reduces long-term distress and increases survival in selected cases.

If palliative care is seen only as relevant to the end-of-life phase, patients who have non-malignant disease are denied expert help for complex symptoms. Timely management of physical and psychosocial issues earlier in the course of disease prevents intractable problems later (Box 3.2).

What are the patient's needs and what is the patient's understanding?

The causes of a patient's symptoms are often multifactorial, and a holistic assessment is central for optimum management. Assessment of the patient's understanding of the disease, understanding their future wishes and acknowledging their concerns, will help the team plan and implement effective support. Patients will have differing needs for information, and will deal with ‘bad news’ in different ways. A sensitive approach, respecting individual requirements, is crucial.

How can patients use palliative care services?

Changes in the provision of SPC services have been forced by the increase in the number of patients who survive malignant disease, as well as recognition of the needs of patients who have non-malignant disease. Many patients will use SPC services for a limited period (weeks to months) for complex problems to be addressed, and then are discharged. They have the opportunity for re-referral if help is required later.

Symptom Control

Good palliative care integrates the control of symptoms with appropriate non-pharmacological approaches, such as anxiety management and rehabilitation (see p. 36).

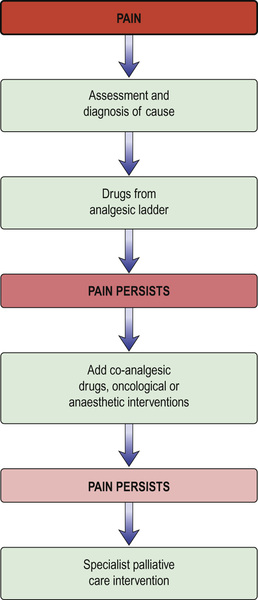

Pain

Pain (see also pp. 818–820) is a feared symptom in cancer. At least two-thirds of people with cancer suffer significant pain. Pain has a number of causes, and not all pains respond equally well to opioid analgesics (Fig. 3.1). The pain is related to the tumour either directly (e.g. pressure on a nerve) or indirectly (e.g. due to weight loss or pressure ulcers). It may result from a co-morbidity such as arthritis. Emotional and spiritual distress may be expressed as physical pain (termed ‘opioid irrelevant pain’) or will exacerbate physical pain.

The term ‘total pain’ encompasses a variety of influences that contribute to pain:

• Biological: the cancer itself, cancer therapy (drugs, surgery, radiotherapy).

• Social: family distress, loss of independence, financial problems from job loss.

• Psychological: fear of dying, of pain, or of being in hospital; anger at dying or at the process of diagnosis and delays. Depression can stem from all of the above.

• Spiritual: fear of death, questions about life's meaning, guilt.

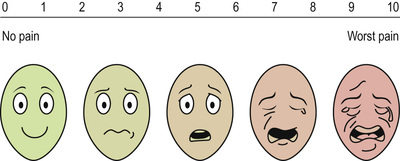

A visual analogue scale for pain can be used (Fig. 3.2).

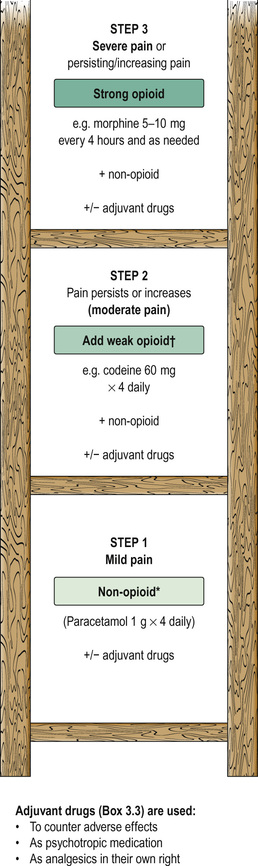

The WHO analgesic ladder

Most cancer pain can be managed with oral or commonly used transdermal preparations. The World Health Organization (WHO) cancer pain relief ladder guides the choice of analgesic according to pain severity (Fig. 3.3, Box 3.3).

If regular use of optimum dosing (e.g. paracetamol 1 g × 4 daily for step 1) does not control the pain, then an analgesic from the next step of the ladder is prescribed. As pain has different physical aetiologies, an adjuvant analgesic may be needed in addition: for example, the tricyclic antidepressant amitriptyline for neuropathic pain (see Box 3.3).

Strong opioid drugs

Dose titration and route

Morphine is the drug of choice and, in most circumstances, should be given regularly by mouth. The dose should be tailored to the individual's needs by allowing ‘as required’ doses; morphine does not have a ‘ceiling’ effect. If a patient has needed further doses in addition to the regular daily dose, then the amount in the additional doses can be added to the following day's regular dose until the daily requirement becomes stable: a process called ‘titration’. When the stable daily dose requirement has been established, the morphine can be changed to a sustained-release preparation. For example:

The starting dose of morphine is usually 5–10 mg every 4 hours, depending on patient size, renal function and whether a weak opioid is already being given.

If there is significant renal dysfunction, morphine should be used in low doses and should not be given in continuous dose regimens (e.g. by subcutaneous infusions) because of the risk of metabolite accumulation (it is renally excreted). In renal impairment, an alternative opioid (e.g. fentanyl) can be given transdermally (e.g. 72-hour self-adhesive patches) or by subcutaneous infusion.

N.B. A word of caution about opioid transdermal patches: serum levels do not change quickly with transdermal patches, and they are also cumbersome to titrate in patients with escalating or unstable pain. They should be kept at a stable dose, and a more dose-responsive preparation used to gain pain control.

If a patient is unable to take oral medication due to weakness, swallowing difficulties, or nausea and vomiting, the opioid should be given parenterally. For cancer patients who are likely to need continuous analgesia, continuous subcutaneous infusion is the preferred route.

Both doctors and patients may have erroneous beliefs, such as the fear of addiction, which mean that adequate doses of opioids are not prescribed or taken. However, iatrogenic addiction is very rare, with the risk being <0.01%; the adverse effects and morbidity from uncontrolled pain are much higher.

Side-effects

The most common side-effects are:

• Nausea and vomiting. These can usually be managed or prevented with antiemetics (such as metoclopramide). Some antiemetic solutions for injection can be combined with an opioid for continuous subcutaneous infusion, e.g. haloperidol or metoclopramide; always check compatibility data.

• Constipation. This is common and should be anticipated with administration of a combination of stool softener (e.g. macrogols) and stimulants, either separately or in one preparation. Naltrexone is a peripherally acting opioid receptor antagonist that is used if response to other laxatives is poor.

If side-effects are intractable, a change of opioid is often helpful.

Toxicity

Confusion, persistent and undue drowsiness, myoclonus, nightmares and hallucinations indicate opioid toxicity. This may follow rapid dose escalation and responds to dose reduction and slower retitration. It may indicate pain that is poorly responsive to opioids and the need for adjuvant analgesics.

Antipsychotics such as haloperidol may help settle the patient's distress whilst waiting for resolution of toxicity. Some patients will tolerate an alternative opioid such as oxycodone better, or an alternative route such as subcutaneous injection.

Adjuvant analgesics

The most commonly used adjuvant analgesics are described in Box 3.3. Other treatments, such as radio/chemotherapy, anaesthetic or neurosurgical interventions, acupuncture and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), may be useful in selected patients.

Regular review is necessary to achieve optimal pain control, including regular assessment to distinguish pain severity from pain distress.

Gastrointestinal symptoms

Anorexia, weight loss, malaise and weakness

These result from the cancer-cachexia syndrome of advanced disease and carry a poor prognosis. Although attention to nutrition is necessary, the syndrome is mediated through chronic stimulation of the acute phase response, and tumour-secreted substances (e.g. lipid mobilizing factor and proteolysis-inducing factor). Thus, calorie–protein support alone gives limited benefit; parenteral feeding has been shown to make no difference to patient survival or quality of life.

Management is supportive unless the patient is fit enough for and responds to anti-tumour drugs. Specific therapies such as eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), fish oil, cyclo-oxygenase (COX) inhibition with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and antioxidant treatments are used.

Advice from a dietician is helpful. Some patients benefit from a trial of a food supplement that contains EPA and antioxidants. Megestrol may help appetite but weight gain is usually caused by fluid or fat. The drug is also thrombogenic and is of little benefit and should therefore not be used.

Corticosteroids were recommended as appetite stimulants and are still commonly used. However, the weight gained is usually caused by fluid, and muscle catabolism is accelerated leading to a proximal myopathy. Any benefit in appetite stimulation tends to be short-lived. Thus, corticosteroids should be limited to short-term use only.

Nausea and vomiting

Nausea and vomiting are common, and often due to use of opioids without antiemetics such as haloperidol 1.5 mg × 1–2 daily or metoclopramide 10–20 mg × 3 daily.

When nausea and vomiting are associated with:

• Chemotherapy. Patients should have an antiemetic, starting with metoclopramide or domperidone, but if the risk of nausea and vomiting is high, give a specific 5-hydroxytryptamine3 (5-HT3) antagonist, e.g. ondansetron 8 mg orally or by slow i.v. injection.

• Chemical causes e.g. hypercalcaemia. Haloperidol 1.5–3 mg daily is the first choice. Metoclopramide is also a prokinetic and therefore useful for emesis due to gastric stasis or constipation. Cyclizine 50 mg × 3 daily is also used.

• Any cause of vomiting. It may be necessary to start antiemetic therapy parenterally by continuous subcutaneous infusion to gain control. If the patient has gastrointestinal obstruction, this route may need to be continued.

Gastric distension

Gastric distension due to pressure on the stomach by the tumour (squashed stomach syndrome) is treated with a prokinetic: for example, domperidone 10 mg × 3 daily.

Bowel obstruction

Metoclopramide is helpful but to be avoided in complete bowel obstruction, where an antispasmodic such as hyoscine butylbromide is preferred. A dose of 60–120 mg/24 hours s.c. is usually recommended, but much higher doses (300–480 mg) may be needed as parenteral hyoscine butylbromide can be rapidly inactivated in humans.

Octreotide (a somatostatin analogue) is commonly used in bowel obstruction to try to reduce gut secretions and the volume of vomitus, but a recent randomized controlled trial failed to show any benefit over placebo. Ranitidine may have a role in reducing gastric secretions.

Physical measures, such as a defunctioning colostomy or a venting gastrostomy, may be helpful. Occasionally, a lower bowel obstruction is resolved with insertion of a stent, or transrectal resection of tumour in selected individuals. Steroids shorten the length of episodes of obstruction, if resolution is possible.

In advanced disease, patients should be encouraged to drink and take small amounts of soft diet as they wish. With good mouth care, the sensation of thirst is often avoidable, thus sometimes preventing the need for parenteral fluids unless otherwise indicated.

Respiratory symptoms

Breathlessness

Breathlessness remains one of the most distressing and common symptoms in palliative care, causing the patient serious discomfort. It is highly distressing for carers to witness. Full assessment and active treatment of all reversible conditions, such as drainage of pleural effusions, or optimization of treatment of heart failure or chronic pulmonary disease is mandatory. In advanced cancer, breathlessness is often multifactorial in origin and many of the contributory factors are irreversible (e.g. cachexia), so a ‘complex intervention’ combining a number of different treatment strategies has the greatest impact. Aspects of breathlessness management are summarized in Box 3.4. Intractable severe breathlessness in a patient who is dying may require sedation in order to provide comfort but more invasive interventions are usually avoided. Non-invasive ventilation (NIV) has been shown to alleviate distressing dyspnoea and is also associated with a reduced opioid requirement; this may be helpful in selected patients.

Breathlessness with panic and anxiety

Patients often experience a panic–breathlessness cycle and fear dying during an acute episode of breathlessness. This is unlikely in chronic disease, unless there is an acute complication, and reassurance will help. The perception of breathlessness is mediated by the central nervous system and can be modulated by thoughts and feelings about the sensation. Education about breathlessness and exploration of psychological precipitators or maintainers can reduce its impact.

Measures to alleviate breathlessness

Non-pharmacological approaches, such as using a hand-held fan, pacing or prioritizing activities to maximize activity within limitations, breathing training and anxiety management, are helpful, along with a tailored exercise programme (Box 3.5). There is no evidence to suggest that oxygen therapy reduces the sensation of breathlessness in advanced disease more than just cool airflow. A hand-held fan should be used before oxygen, unless the latter is indicated by significant hypoxaemia or disease management. Opioids, used orally or parenterally, can palliate breathlessness. If panic/anxiety is significant, a quick-acting benzodiazepine such as lorazepam (used sublingually for rapid absorption) is useful.

Cough

Persistent unproductive cough can be helped by the antitussive effect of opioids (e.g. morphine). Excessive respiratory secretions can be treated with hyoscine hydrobromide 400–600 µg every 4–8 hours but does give a dry mouth. Glycopyrronium is also useful by subcutaneous infusion of 0.6–1.2 mg in 24 hours.

Other physical symptoms

People with cancer may develop other physical symptoms caused by the tumour directly (e.g. hemiplegia due to brain secondaries) or indirectly (e.g. bleeding or venous thromboembolism due to disturbances in coagulation). Symptoms may also result from treatment, such as lymphoedema following treatment for breast or vulval cancer, or heart failure secondary to anthracycline or trastuzumab therapy. The principles of holistic assessment, reversal of reversible factors and appropriate involvement of the multiprofessional team should be applied.

Lymphoedema

The pain and disabling swelling associated with lymphoedema can be alleviated through complete decongestive therapy (CDT), a treatment that employs a massage-like technique and comprises manual lymphatic drainage, compression bandaging and gentle exercise. Diuretics should not be used. Referral to a specialist lymphoedema therapist or nurse is useful.

Fatigue

Fatigue is a significant and debilitating problem for palliative patients. It has physical, cognitive and affective components; unlike normal tiredness, it is not relieved by usual sleep or rest. An assessment for reversible contributory factors, such as anaemia, hypokalaemia or over-sedation due to poorly optimized medication, should be undertaken. Management strategies are:

• non-pharmacological: relaxation, sleep hygiene, resting ‘pro-actively’ rather than collapsing when exhausted, and planning, pacing and prioritizing daily activities

• pharmacological: low-dose methylphenidate (central nervous system stimulant), or short-term corticosteroids used in conjunction with the SPC team, may help.

Loss of function, disability and rehabilitation

Some of the most pressing concerns include increasing physical frailty, loss of independence, and perceived burden on others. Evidence suggests that functional problems are not routinely assessed, and not as well managed as pain and other symptoms. Rehabilitation can:

• contribute to patients' quality of life by providing strategies for managing declining physical function and fatigue, and by offering resources that might make life easier for patients and carers (e.g. equipment or a wheelchair)

• support patients' adaptation to disability, helping them to increase social participation and find fulfilment in everyday living

A referral to physiotherapy or occupational therapy is helpful for patients whose ability to carry out daily activities is compromised by illness or its treatment. However, it must be remembered that effective rehabilitation is a team effort and is not solely the domain of nursing and allied health professionals. Doctors also have a major role to play in attending to functional problems and fatigue; they should not see these as inevitable, unavoidable and insoluble.

There is a need to take into account changing performance status as well as changes in goals and priorities. It can be helpful to identify short-term, achievable goals and focus on these. Most patients wish to remain at home for as long as possible and to die at home, given adequate support. Patients' community rehabilitation needs should not be neglected.

Psychosocial issues

Depression is a common feature of life-limiting and disabling illness, and is often missed or dismissed as ‘understandable’. However, it may well respond to the usual antidepressant drugs and/or to non-pharmacological measures such as cognitive behavioural therapy, increased social support (e.g. day therapy) and support for family relationships. Such interventions can make a big difference to the patient's quality of life and ability to cope with the situation.

Extending Palliative Care to People with Non-Malignant Disease

The principles of palliative care can be applied throughout medical practice so that all patients, irrespective of care setting (home, hospital or hospice), receive appropriate care from the staff looking after them and have access to SPC services for complex issues. Some principles are outlined in Box 3.6. Patients who have chronic non-malignant disease, such as organ failures (heart, lung and kidney), degenerative neurological disease and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection:

• have a similar or greater symptom burden than people with cancer

• may live longer with these difficulties

• benefit from a palliative care approach with access to SPC for complex problems.

There may be a less clear end-stage of disease but the principles of symptom control are the same: holistic assessment, reversal of reversible factors and multiprofessional support.

Patients who have non-malignant disease may have very close relationships with their usual team, and an integrated approach is essential to allow optimization of disease-directed medication as well as palliation. People with non-malignant disease may live for years with a difficult illness and so their palliative care needs to differ in some respects from that of cancer patients (Box 3.7). However, symptom management is largely transferable, with some exceptions and extra complexities as outlined below.

Throughout the course of the illness, careful open discussion of possible future options is essential. Early discussion of difficult choices is as helpful for patients who have non-malignant disease as it is for those with cancer, and these discussions are ideally held when the patient is relatively well and outside an acute episode. Discussions delayed until the crisis of acute admission may lead to acceptance of an invasive treatment that is later regretted by the patient.

Heart failure

There are special considerations with respect to cardiac medication in advanced disease:

• Drugs that are commonly used in palliative care but usually contraindicated in heart failure, such as amitriptyline and NSAIDs, may be appropriate when the patient is dying.

• Sudden death is more common than in patients who have malignancy and a patient may have an implanted defibrillator in place. If present, these devices should be reprogrammed to pacemaker mode in advanced disease because they have not been shown to improve survival in severe heart failure and it will be distressing for patient, carer and staff if the defibrillator discharges as the patient is dying.

• Peripheral oedema can become a major problem and more resistant to diuretic therapy; careful balancing of medication regimens is therefore required. Ultimately, symptom relief is prioritized over renal function.

• Medications should be rationalized to reduce polypharmacy, e.g. ceasing drugs prescribed to reduce long-term secondary risk (e.g. statins) and continuing drugs that help symptom control (including angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, which benefit symptoms as well as survival). Beta-blockers may have to be stopped if the patient can no longer maintain non-symptomatic hypotension.

Regarding statins, a recent randomized trial of withdrawal versus continuation of statin in those thought to be in the last year of life showed no detrimental effect on quality of life with withdrawal.

Chronic respiratory disease

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

COPD is the most common chronic respiratory disease. Patients may live increasingly restricted lives for years, rather than the months or weeks that are common once someone with cancer becomes breathless. Patients usually reach late middle age or old age before becoming very disabled, and an elderly spouse often has to carry significant physical burdens.

Because of the risk of dependency, falls and memory problems, non-pharmacological approaches to anxiety are more appropriate than benzodiazepines (see Box 3.5 ). Short-acting benzodiazepines should be reserved for severe panic episodes.

Palliative care breathlessness services can be very helpful for those unable to comply with pulmonary rehabilitation. Emergency admissions to hospital for non-medical reasons are often due to anxiety and the support offered by community palliative care services working with respiratory teams can help prevent these.

Other chronic respiratory diseases

Other chronic respiratory illnesses that often require palliative care include:

• Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. This has a trajectory similar to that of cancer, with rapidly developing breathlessness and cough. The breathlessness of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis is particularly frightening but may respond well to opioids; early access to hospice services is particularly relevant to help with symptom control and anxiety.

• Cystic fibrosis. Patients are teenagers or young adults who usually have known their respiratory team all their lives. An integrated team involving SPC clinicians ensures good symptom control and provides useful support when difficult decisions have to be made about treatments (e.g. lung transplant), as well as offering psychosocial care to the family.

• Primary pulmonary hypertension. Patients are often young and treated far from home in specialist centres. They require symptom control in close consultation with the medical team, and it is essential for any dependent children to receive the care they need.

Ventilatory support (see pp. 1163–1167)

For many patients who have respiratory failure, non-invasive ventilation (NIV) has superseded the use of intermittent positive pressure ventilation (IPPV) on intensive therapy units. However, there are patients who are likely to need IPPV during admission for an acute exacerbation. For some of this group, life has become burdensome, rendering the net benefit for this procedure less or negligible. These patients should be put in contact with hospice services when they are relatively stable (not during acute exacerbations), anticipating an alternative place of admission in the event of subsequent deteriorating health.

Opioid titration in non-malignant respiratory disease

In non-malignant respiratory disease, opioid titration may need to follow a different pattern from that used in malignant disease, in which many patients are already on opioids for pain control before they develop breathlessness. Some clinicians recommend a cautious approach for these chronically breathless patients who have non-malignant disease, but the evidence indicates that those with adequate renal function may safely be started on 5–10 mg modified release morphine, given appropriate monitoring. Constipation can be a problem (see p. 34) but recently naloxegol (a pegylated derivative of the µ-opioid receptor antagonist naloxone) has been shown to be helpful without reducing the analgesic effect of opioids.

Renal disease

All care for patients who have end-stage chronic kidney disease (CKD) is directed towards maintenance or improvement of renal function. Prescribing is complicated, particularly if patients are receiving dialysis. Care must be taken not to cause renal damage inadvertently with potentially renotoxic medication, and close liaison with the renal team is mandatory.

In patients who have CKD, co-morbidities such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes or osteoporosis may cause greater problems than the renal disease. Those with a fluctuant course of symptoms, such as the 25–33% who have coexisting cardiac disease, bear disproportionately greater physical and psychological burdens.

Patients who are on dialysis

Patients attend three times per week (and receive social support from this). Thus additional attendance at a hospice day therapy service may be too tiring. If further support from SPC services is needed, then outpatient clinics, community support (for patient and/or carer) or even admission may be more suitable.

Withdrawal of dialysis

Withdrawal of dialysis is necessary if the effort of attendance becomes too great when there is little improvement in quality of life and the impact of other co-morbidities becomes intrusive.

If there is no residual renal function, survival after withdrawal of dialysis is likely to be a few days at most. In contrast, patients who have some residual function (usually those who have had dialysis for only a few weeks or months) may live for months or even a year after withdrawal. Patients and carers need to understand these differences in order to make informed choices.

Patients who are not on dialysis

Maximizing and preserving remaining renal function are critical considerations in deciding which medications can or should be prescribed:

• Medication that accelerates loss of renal function may markedly reduce survival in patients who can live on very little remaining renal function.

• The renal impact of both dose and drug choice must be taken into account. For example, morphine and diamorphine metabolites accumulate in end-stage renal dysfunction; thus strong opioids such as alfentanil or fentanyl should be used instead.

Close liaison with the medical team is essential for drug prescribing.

Neurological disease

People who suffer from chronic degenerative neurological diseases have a considerable burden of palliative care needs, including:

• difficulties in swallowing (e.g. in motor neurone disease)

• loss of mental capacity – the ability to understand, weigh up, come to a decision and communicate that decision.

Ideally, discussions regarding the patient's wishes should take place in advance, if the patient is able to do this, so that these can be supported.

Motor neurone disease

Motor neurone disease is usually rapidly progressive, often requiring hospice support. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (see p. 213) feeding may be required. In addition, if ventilatory failure develops, nocturnal NIV may be offered. Patients and their carers need to understand:

• why this treatment has been offered (to prevent hypercarbia and morning headache and confusion)

• when this treatment will be withdrawn (when it is no longer helping to maintain or improve quality of life in the face of advancing disease).

Patients need to be given a clear understanding of what alternative symptom control will be offered at withdrawal.

Multiple sclerosis

Pain is often prominent in multiple sclerosis because of muscle spasm; patients may become too disabled to attend outpatient clinics and then receive very little surveillance. Hospice day therapy service, rehabilitation and support for the family can make a huge impact on quality of life.

Dementia

Dementia-related palliative care needs arise in the context of neurological conditions that:

• tend to occur in older people (Alzheimer's disease and multi-infarct dementia)

• also affect younger people (e.g. Parkinson's disease, multiple sclerosis, Huntington's disease).

It is often difficult to ascertain whether these patients are in pain. An assessment tool that assesses behavioural response to pain, such as the Abbey and Doloplus, which uses vocalization (e.g. groaning), facial expression (e.g. frowning), change in body language (fidgeting, rocking), behaviour change (e.g. confusion, refusing to eat) and physical changes, can be useful.

Dementia poses special problems with respect to inpatient palliative care. For example, in the UK, many hospice inpatient units will not accept mobile patients who have dementia because the patient's safety cannot be guaranteed. However, they will care for those at the end of life with other SPC needs – for example, a distressed young family – or pain, and will often support other services by providing advice on symptom control.

Palliative Care of the Frail Elderly

People worldwide are living longer as diseases, both communicable and non-communicable, are better managed. However, the palliative care needs of older patients often go unrecognized and are therefore under-treated. The physiological effects of ageing itself are compounded by co-morbidity, polypharmacy and unhealthy lifestyles. These factors lead to a higher mortality than expected, a heavy symptom burden and shortened life expectancy, compared to those who remain in good health at the same advanced age. Recognition of and attention to the care of these patients can improve outcomes by encouraging carers to produce individual care plans for the elderly frail.

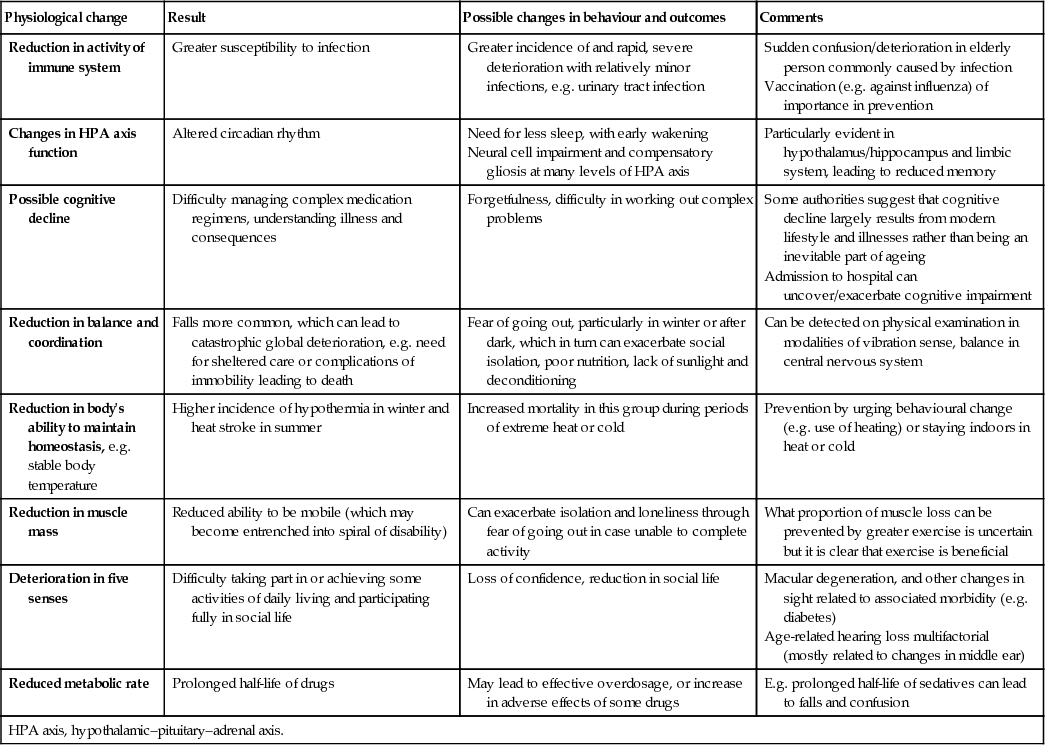

Frailty is an emerging syndrome in the elderly. It has many definitions but can be thought of as a state of extreme vulnerability with ‘a progressive physiological decline in multiple organ systems’. This leads to a marked loss of function, loss of physiological reserve and an increased vulnerability to disease and death. There are a number of physiological changes that are associated with normal ageing (Box 3.8), as well as the cumulative impact of chosen or imposed ‘unhealthy’ ways of life and chronic pre-existing diseases. The proportion of detrimental changes that can be prevented or ameliorated by different behaviour earlier in life, or by supporting people to maintain healthy habits into older age, is debatable. Box 3.9 shows the ‘five ways to wellbeing’, which, if practised with other public health teaching on moderate alcohol intake, maintenance of a healthy weight and rejection of smoking, would help to preserve health and activity as life advances.

Frailty, however, implies vulnerability to a loss of function in many areas. There are a number of scoring indices for frailty. The Fried Frailty Score assesses:

• weakness (decreased hand grip strength)

• physical inactivity (low energy expenditure)

• weight loss (body mass index <18.5 or >5% weight loss in the last year).

A score of 3 or more defines frailty, although slow walking, low physical activity and weight loss, as well as cognitive impairment, were independently associated with disability and a poorer prognosis.

Assessment of the frail elderly person presenting in a medical setting

The frail elderly person may present acutely to medical services in a number of different ways. It is essential for there to be an individual focus on improving and/or maintaining the current quality of life. As there is a high mortality in this group, all care of the frail elderly person can be considered ‘palliative’. A central tenet of palliative care is to assess the presence and severity of symptoms and to elicit the patient's priorities for future management. This will identify frail adults. Thus acute hospital admissions provide an opportunity to begin discussions with patients and their families about their preferences for future care. Treatment should be offered on the basis of individual need and potential for benefit for that individual, rather than chronological age. The aims of assessment and management are to:

• identify and treat reversible causes of decline

• detect and control troublesome symptoms and form individualized treatment plans

• screen for weight loss, pain, dyspnoea, falls, depression and insomnia

• assess severity of frailty and identify those with worse prognostic indicators (see above)

• communicate to the patient and the family the prognostic implications of frailty, its likely course, and available support.

Context of the consultation

Care with regard to the setting and conduct of the consultation is necessary to enable individuals to tell their story and make their wishes clear. Assessment may need to be phased to obtain all the necessary information and should involve the multidisciplinary team, as medical and social care needs can often not be differentiated; one is only possible when the other is implemented effectively.

The following are questions to ask:

• Is the individual frail elderly person being treated in a dignified way? Are they being called by their title and surname, and not a diminutive? Are people shouting at them or belittling them? Are they dressed, covered up, sitting comfortably and/or adequately supported if in bed?

• Does the patient have problems with hearing or sight? Do they have particular communication needs, e.g. a quiet side room to avoid background noise, help with their hearing aid (is it in? is it working?), assistance finding their glasses.

• Do they need help with information to support their use of drug treatment or understanding of their illness?

• Have they come from home or somewhere else? Does this setting suit them or is it now part of the problem (see Box 3.8)?

A full assessment of mental capacity is necessary. In those who are unable to provide their own full history, details should be sought from other sources of information such as:

• those looking after them in their nursing or residential home

• their relatives who support them to live independently/with whom they live.

Ensure that you know whom to contact for advice if you have any doubts about the individual's ability to make informed decisions for themselves. Always take advice from a senior clinician if you have doubts.

Management of the frail elderly person

Following the comprehensive assessment, an early priority is to reverse what is reversible; rehabilitation should be provided, again tailored to the individual's potential for improvement or adaptation.

• Treat symptoms. Investigation and treatment of known medical problems should be appropriate for the individual (Box 3.10). Investigation and management of any new disease will follow the general principles as for other age groups but remembering that the frail elderly will have a high mortality in the year after admission.

• Discuss the future sensitively. Discussions about wishes for future care are complex with anyone who has life-threatening disease. They may not see themselves that way and assumptions should not be made about what frail elderly individuals want or how they view their health status. They may not feel that they are particularly ill or even that they have a poor prognosis, despite having reached a great age. General medical management needs to be integrated with symptom control. The SPC team should be contacted for advice or involved with management when there are difficulties with this or with complex discussions with the individual or their family.

• Review the drug chart. One feature of frailty is that patients are often taking large numbers of drugs, some of which may be causing disabling adverse effects without any immediate benefit for that individual's quality of life. Reviewing every drug with the patient may be very helpful in lessening symptom burden and may help reduce confusion and sedation.

In summary, palliative care should be available to everyone on the basis of need. It is frequently not offered to the frail elderly and symptoms are known to be both under-detected and under-treated in this group. Ensure this does not happen when you are caring for a frail elderly person. Contact the palliative care team for advice, even if referral for transfer of care is not necessary.

Care of the Dying

Most people express a wish to die in their own homes, provided their symptoms are controlled and their carers are supported. However, patients die in any setting and so all healthcare professionals should be proficient in end-of-life care.

Reports of inadequate hospital care have led to the development of integrated pathways of care for the dying. Pathways act as prompts of care, including psychological, social, spiritual and carer concerns in those who are diagnosed as dying. The latter is a decision reached by a multiprofessional team through careful assessment of the patient and exclusion of reversible causes of deterioration.

Do not attempt resuscitation (DNAR) orders

• The resuscitation status of every patient should be discussed by senior doctors at the time of admission and the decision documented in the notes.

• Many hospitals have specific DNAR forms. Deciding a person's resuscitation status is a careful balance of risk versus benefit. The patient's co-morbidities and pre-morbid quality of life should be taken into account.

• The patient and family should be involved in this discussion, and the medical reasoning behind the decision explained. If the patient requests that cardiopulmonary resuscitation is not performed in the event of cardiopulmonary arrest, those wishes should be respected.

Remember that a decision not to resuscitate a patient is not the same as the decision to withhold other treatment. A patient who is not for resuscitation may still be eligible for antibiotics, fluids, endoscopy and even surgery. Management should remain positive, allowing the patient to die free of distress and with dignity.

Care of the dying tools

The Liverpool Care Pathway (LCP; Box 3.11 ) has come in for a great deal of criticism. It is a four-stage end-of-life tool designed to transfer the standard of hospice care of the dying into the hospital (see Box 3.10 ). Now adapted for any setting, it was the most commonly used pathway for care of the dying in the UK and is still in use in several other countries.

The LCP has provision for departures from the ‘prompts of care’ – for example, discontinuation of intravenous antibiotics or parenteral fluids – if a clinical need can be demonstrated. The patient is reviewed regularly (at least daily). Occasionally, the patient improves whilst on the pathway and can be returned to usual care if this is deemed more appropriate by the clinical team. For those who do not improve, the LCP prompts advanced prescription of medication to ease the symptoms most likely to arise in the dying phase (pain, breathlessness, nausea, agitation and excess respiratory secretions) to allow timely action.

Engagement with family and carers is vital, and it should not be assumed that they will recognize or understand the signs of imminent death. The LCP has supportive information leaflets that carers should find useful.

UK national hospital audits have assessed and monitored the level of care documented against the standards set in the LCP. However, following some well-publicized errors of implementation of the tool in the UK in 2013–2014, and in the face of a lack of randomized controlled trial evidence to support its use, the LCP was withdrawn and replaced by individual care plans outlined by the Leadership Alliance for the Care of Dying People. Since then, a cluster randomized trial of the LCP in cancer patients has reported no significant difference in overall quality of care, but did show improvements in coordination of care, treatment with dignity, family self-efficacy, and respect and information and decision-making.

Significant websites

http://www.cancerresearchuk.org UK charity

http://www.cuh.org.uk Breathlessness information

http://www.macmillan.org.uk UK patient organization

http://www.palliativedrugs.com Palliative drugs information

http://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/journal/palliative-medicine Palliative medicine