‘Had Keynes begun his first few chapters with the simple statement that he found it realistic to assume that modern capitalistic societies had money wage rates that were sticky and resistant to downward movements, most of his insights would have remained just as valid . . .’

P. Samuelson, 19631

‘. . . expectations, since they are informed predictions of future events are essentially the same as the predictions of the relevant economic theory.’

J. F. Muth, 19612

By the mid-1970s the Keynesian episode was over, though some fragments were rescued from the wreck. In the following years, economics reverted to its pre-Keynesian origins. ‘Everything that Keynesians took as policy targets’, writes Orsola Constantini, ‘were now taken to be necessary characteristics of a well-organized economic system.’3

Why did this unravelling happen? The accepted answer is that the reaction against Keynesianism was triggered by the failures of Keynesian policy in the 1970s, in particular to control the inflation produced by its commitment to full employment. But in fact the reaction against Keynesianism had been biding its time for many years among those economists who had never accepted Keynes’s theory and had acquiesced only reluctantly in Keynesian policy. It can be traced back to the compromise that had launched the Keynesian revolution.

In the neo-classical economic models, full employment was assured by wage and price flexibility. Economists even before Keynes had recognized that these mechanisms were partially inoperative, because ‘frictions’ – business and union monopolies, fixed wage contracts, unemployment benefits and other government interferences – impeded them. Hence some ‘classical’ economists were willing to support public works, or countercyclical policy, to maintain employment, while preserving models of the economy that assumed full market adjustment.

Keynes produced a model which had nothing to do with the existence of such institutional obstacles to wage and price adjustment. What he aimed to show was that, even without these frictions, a market economy would not be optimally self-adjusting. There was no ‘automatic tendency’ for the rate of interest to fall sufficiently to employ all intended saving, nor for real wages to fall sufficiently to employ all those looking for work. Whether or not equilibrium or market-clearing prices for saving or work existed, they were not known, or knowable, to those whose decisions determined prices in the market. In a competitive market system, uncertainty attaching to such prices was inherent and ineradicable.

The counterattack started not with a rejection of Keynesian policy prescriptions, but with an assault on Keynes’s theory. In essence, the non-Keynesians invented new arguments to show why flexible moneywages would always maintain full employment.4 Since, unfortunately, wages were not flexible, Keynesian policy could be justified on political, efficiency and, perhaps, human grounds. One had only to assert that, with (unexplained) time-lags in the price-adjustment process, any policy which averted a slump was good. This was the essence of the truce between Keynes and the Classics. They carried off the theoretical honours, he won the policy war.5

The origins of the attempt at synthesis can be traced back to the Oxford meeting of the Econometric Society in September 1936, which started the mathematicization of Keynes’s General Theory. At this meeting, John Hicks presented his ‘classroom gadget’ – the IS/LM (investment-savings, liquidity-money) model – which he published in the June 1937 issue of Econometrica.6 Hicks reduced the General Theory to a multi-equational system that yielded a Walrasian full employment solution in the absence of restrictions on the movement of interest rates and wages (the neo-classical case) or a quantity-adjusted equilibrium if wages and interest rates were fixed (the Keynesian case). He did not say which was more likely.

The IS/LM apparatus was not a theory, it just provided different ways of arranging possibilities. In Hicks’s own view, which came to be widely accepted, Keynes’s ‘general’ theory was a ‘special’ case of the more general neo-classical theory, with restrictions imposed on the movement of wages and interest rates. Given such price ‘stickiness’, choice of policy instrument depended on the slope of the schedules: Keynesians emphasized situations where monetary policy is relatively ineffective, because of liquidity preference, and investment is relatively unresponsive to changes in interest rates. They preferred fiscal to monetary policy because it acted directly on the components of demand.

Alan Coddington calls the IS/LM model ‘an analytical receptacle of quite astonishing versatility and resilience within which even the antagonists in protracted controversies have been able to find a common framework for their disputes’.7 According to Warren Young it became ‘the conceptual manifestation of the quest for continuity and certainty’, providing the authorized means for economics students to digest the General Theory.8 It is through this mathematically elegant paradigm, reduced to a famous diagram, that those developing and applying Keynes’s ideas were led to understand them. (For the IS/LM diagram and explanation, see Appendix 7.1, p. 203.)

By the 1950s, Paul Samuelson had written that economists had ‘worked toward a synthesis of whatever is valuable in older economics and in modern theories of income determination. The result might be called neo-classical economics and is accepted in its broad outlines by all but about 5 per cent of extreme left wing and right wing writers.’9

The neo-classical synthesis was predicated on two contradictory beliefs: belief in the optimizing agent, and belief in wage and price rigidities. The former preserved the neo-classical structure of microeconomics, while the latter provided the rationale for interventionist policies to offset collapses in investment. There was now a logical gap between microeconomics and macroeconomics, since wage stickiness and the resulting persistent unemployment is inconsistent with individual optimizing behaviour. Keynes had set out to fill logical gaps in the classical theory. Classical economists now started to complain that Keynesian models were not properly grounded in microeconomics: they lacked incentives like market prices to push the human puppets this way and that; labour supply was assumed to be fixed; household savings were assumed to be dependent only on current income; business investment was deemed to depend on expected sales rather than on profitability. It was a ‘demand-determined’ world view, which left hardly any scope for supply adjustments. None of this mattered much against the background of the huge demand-deficiency of the 1930s. It became much more important in the high employment economy of the postwar years.

The revolt against the Keynesian policy orthodoxy is popularly, and rightly, associated with the Chicago economist Milton Friedman. However, Friedman built on an undercurrent of dissatisfaction with the Keynesian approach to economic policy which had started long before Keynesian policy failures gave it political voice.

The origins of an organized ‘counter-orthodoxy’ – the intellectual and political reaction to the post-war consensus – can be traced back to the 1938 ‘Colloque Walter Lippmann’, a conference arranged by the French philosopher Louis Rougier to discuss Lippmann’s 1937 book An Enquiry into the Principles of the Good Society. It was at the colloquium that the German economist Alexander Rüstow coined the term ‘neo-liberalism’ to describe the intellectual movement that sought to reboot the ‘classical’ liberalism of the pre-Great Depression era, and which had begun with debates in the universities of Vienna, Freiburg and Paris and the LSE. The neo-liberal target was totalitarianism, as manifested in National Socialism and Bolshevism. Keynes should have been an ally of these neo-liberals, but the large dose of interventionism he deemed necessary to support a market economy led them to view Keynesianism in effect, if not in intention, as an ally or at least a stalking horse for the totalitarianism they were fighting. The neo-liberal solution to the ills of laissez-faire was not to insert government, but to embed the market economy in a constitutional, rule-bound order (hence the German Ordoliberalismus) which guaranteed free competition and denied the state discretionary power to modify market processes. A social safety net should be provided ‘outside the market’ for victims of economic or personal misfortune.

Keynes’s relationship to this defence of classical economics comes out very clearly in his response to Hayek’s Road to Serfdom (1944). Hayek’s argument, in a nutshell, was that ‘once the free working of the market is impeded beyond a certain degree, the planner will be forced to extend his controls until they become all-comprehensive’. Hayek did not attack Keynes by name. But he certainly had him in his sights as the intellectual leader of those who ‘believe that real success [in combating economic fluctuations] can be expected only from public works undertaken on a very large scale’. Hayek did not accuse such economists of the coercive intent of the totalitarians. But he argued that if governments were determined not to allow unemployment at any price and not to use coercion, the result would be increasing misallocation of resources and rising inflation. He warned that ‘we shall have carefully to watch our step if we are to avoid making all economic activity progressively more dependent on the direction and volume of government expenditure’.10

Keynes responded to Hayek in a letter of 28 June 1944. He congratulated him on having written ‘a grand book . . . morally and philosophically I find myself in agreement with virtually the whole of it; and not only in agreement, but in a deeply moved agreement’.

However, he had three objections. First,

you admit . . . that it is a question of knowing where to draw the line. You agree that . . . the logical extreme [of laissez-faire] is not possible . . . But as soon as you admit [this] you are done for . . . since you are trying to persuade us that so soon as one moves an inch in the planned direction you are necessarily launched on the slippery path which will lead you in due course over the precipice.

Secondly, Keynes rejected, on prudential grounds, Hayek’s belief that depressions had to be allowed to run their course. This, he said, ‘would only lead in practice to disillusion with the results of your philosophy’. In effect, Keynes accused Hayek of putting economic ideology ahead of statecraft. It was Hayek’s policy, not Keynes’s, which endangered liberalism, by threatening to provoke revolution.

Thirdly, Keynes denied that the totalitarian slide would occur in societies with robust traditions of freedom and democracy. ‘Dangerous acts can be done safely in a community which thinks and feels rightly, which would be the way to hell if they were executed by those who think and feel wrongly.’11 This is a strong, but static dictum. What it ignores is Hayek’s claim that the stock of ‘right feeling’ can be depleted by government policy: it is not independent of the acts being done. It then becomes a matter of judgement as to which set of economic and social practices is most likely to preserve the moral values that Hayek and Keynes shared.

The debate, as we can see, was about a fundamental question: was Keynesianism (and, more broadly, social democracy) an antidote to totalitarianism or the thin end of the wedge? Here one can say that Keynes won the major argument, but lost the minor one. Keynesianism as a policy nowhere led to serfdom, but it did lead to inflation.

The Road to Serfdom was the inspiration for the Mont Pelerin Society founded by Hayek in 1947. An early member of the society was Milton Friedman. Friedman was not in the business of synthesis, but of counter-revolution. He attacked Keynes’s doctrines in order to demonstrate the futility of Keynesian policies. He recalled that:

During my whole career, I have considered myself somewhat of a schizophrenic . . . On the one hand, I was interested in science qua science, and I have tried – successfully I hope – not to let my ideological viewpoints contaminate my scientific work. On the other, I felt deeply concerned with the course of events and I wanted to influence them so as to enhance human freedom. Luckily, these two aspects of my interests appeared to me as perfectly compatible.12

This is disingenuous. The motivation for his work was thoroughly political. Friedman restated neo-classical economics in order to expel the expanded Keynesian state from the economy. Shrinking the state was the scarcely avowed aim of his economics.

Friedman believed that market incentives were normally effective. This meant that economies were normally stable at what he called their ‘natural’ or ‘equilibrium’ rate of unemployment. Government interference in the structure of market incentives was the chief cause of their rocking motion. In their efforts to minimize unemployment – in Friedman’s terms, to reduce it below its ‘natural rate’ – Keynesian governments pumped too much money into the economy, feeding misperceptions about prices, which fed inflation. They then tried, somewhat ineffectually, to stop the inflation by incomes policy, which destroyed price-adjustment mechanisms in the labour market. Governments should therefore be tied down like Gulliver, to rules that severely limited their discretion to expand the money supply at will. This was very much in line with Hayek, and can be traced back to Ricardo.

Friedman stuck firmly to the neo-classical micro-foundations. These showed that persistent mass unemployment was impossible. He went beyond the neo-classical synthesizers by claiming that inflexible price behaviour was not a sociological datum, but was caused by government interference with the working of the credit and labour markets. He thus had his own explanation for the otherwise unexplained lags in the price-adjustment mechanism. Technically, Friedmanism was an attempt to reunify orthodox microeconomics and the new macroeconomics by emasculating macro-policy to the barest minimum.

Friedman’s monetarism harked back to the golden age of the Quantity Theory of Money, which had inspired the efforts of the monetary reformers of the 1920s, including Keynes himself. The economy would not normally misbehave – or seriously misbehave – if money was kept ‘in order’. To put it another way, if the quantity of money was right, there would be the right amount of spending. The success of governments in disturbing the economy for political ends showed the power of money; now that power had to be harnessed by an independent central bank to prevent it from disturbing the economy.

Friedman developed and broadened his onslaught on Keynesian doctrines through a sequence of interrelated arguments running from the 1950s to the late 1960s. By 1968 his artillery was fully assembled. He won a Nobel Prize in 1976 for his achievement in the ‘field of consumption analysis, monetary history and theory, and stabilization policy’. The effect of his attack was to destroy most of the Keynesian case for demand-management.

His ‘permanent income hypothesis’ (1957) was part of his claim that market economies were normally self-adjusting to full employment. Keynes’s consumption function made spending depend on current income only. This meant that temporary shocks exert a strong influence on aggregate demand. In Friedman’s view, this exaggerated the effects of fluctuations in demand. He modelled rational, forward-looking individuals as smoothing their consumption over their expected permanent (lifetime) income.13 This had the consequence that, in a downturn, spending fell less than current income: expecting their incomes to fall only temporarily, people would use up their savings or borrow on the strength of their ‘normal’ earnings, expecting to rebuild their savings or pay back their debt when ‘normal’ times returned. There was correspondingly less need for the government to increase the budget deficit or (say) redistribute income to those with a higher propensity to consume. Spending out of permanent income kept the economy nearer full employment.14

At the heart of Friedman’s monetary theory was his restatement of the Quantity Theory of Money (1956):15

PQ = f(M)

P = g(M)

where P is the price level, Q is output, f is a function of money in the short-term, and g a function of it in the long-term. In the short-term, changes in money can affect output, but ultimately a change in the quantity of money will lead to a proportional change in the price level.

Friedman took the strategic decision to base his case on what he called ‘the stable demand function for money’. This meant denying the existence of Keynes’s ‘speculative demand for money’. Friedman claimed that Keynes’s restriction of portfolio choice to money and bonds was unjustified. Portfolio choice was a choice between money and all utility-yielding forms of wealth, not just bonds. Because there was an opportunity cost to holding money (it yielded no interest), cash balances would always be kept at a minimum. People would use any surplus cash they had to buy shares in companies or real estate. The extended theory of portfolio choice thus confirms the assumption of the ‘simple theory’ that, faced with a surplus or deficit of money, people would aim to restore their real balances by increasing or reducing their spending. This restores the money multiplier and the link between money and prices.

In two gigantic books, Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960 (1963)16 and Monetary Trends in the United States and in the United Kingdom (1982),17 Friedman and Anna Schwartz attempted to verify Friedman’s restatement of the QTM empirically. Their double conclusion was that the velocity of circulation – the speed with which a unit of money changed hands – remained remarkably constant across cycles, and that in all cases of cyclical fluctuations the change in the broad money stock preceded the change in money incomes. The econometrics, and consequently the conclusions, of Friedman and Schwartz were heavily criticized by Hendry and Ericsson.18 Inevitably, the empirical examination was inconclusive: it always is. Friedman was not unduly worried.19 Like Keynes, he understood that the best economics could do was to wring ‘reasonable conjectures from refractory and inaccurate evidence’.20

The Friedman–Schwartz view that the Great Depression of 1929– 32 was caused by the failure of the Fed to prevent the collapse of the money supply has become orthodox. It influenced Ben Bernanke, Chairman of the Federal Reserve Board from 2006 to 2014, and the policy of quantitative easing adopted to meet the 2008–9 recession. In addition, just as the depression was caused by the central bank printing too little money, so inflation was due to the central bank printing too much money: ‘inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output’.21

Next in Friedman’s line of fire was the Keynesian stabilization theory. This was demolished by replacing Keynes’s ‘uncertain expectations’ by ‘adaptive expectations’. Adaptive expectations postulates that people learn from experience; namely, they learn that monetary expansion leads to inflation. This means that monetary policy cannot peg either interest rates or the rate of unemployment for more than very limited periods.

Regarding the first, Friedman maintained:

let the higher rate of monetary growth produce rising prices, and let the public come to expect that prices will continue to rise. Borrowers will then be willing to pay and lenders will then demand higher interest rates . . . every attempt to keep interest rates at a low level has forced the monetary authority to engage in successively larger and larger open market purchases.22

In his Presidential Address to the American Economic Association, entitled ‘The Role of Monetary Policy’ (1968), Friedman mounted a frontal assault on the Keynesian Phillips Curve, the view that there existed a stable trade-off between inflation and unemployment.23 We have seen that, as an empirical hypothesis, the Phillips Curve started to collapse towards the end of the 1960s, as the ‘trade-off’ worsened, producing simultaneously rising inflation and unemployment. The key mistake of the Keynesians, said Friedman, was that they assumed that wage bargainers had fixed price expectations (appropriate perhaps for the nineteenth-century world of long-run price stability, but obsolete for inflationary times). This inevitably led to the conflation of the short-run effects of monetary policy with the long-run. Lower unemployment could only be obtained if wage inflation lagged behind the actual inflation rate. However, pronounced inertia in face of continuous experience is contrary to the microeconomic theory of optimization. Rather, it was reasonable to assume that people adapted their behaviour to the experience of inflation.

Thus, if the government, in order to reduce unemployment, causes aggregate demand (or, in Friedman’s terms, the money supply) to grow faster than the economy’s productive capacity, the first effect will be to stimulate the economy; but the ultimate result will be to raise prices with no effect on employment or output. This is because workers will initially accept additional employment at the higher nominal wage brought about by the stimulus, without realizing that firms will in turn raise their prices, eroding workers’ gains in real-wage terms and thus reducing their willingness to work back to the level it had been before. People base their inflation expectations on inflation in the previous period. As a result, the inflation caused by the government’s stimulus becomes ‘built in’ to workers’ expectations. (See Appendix 7.2, p. 205, for a more thorough account of adaptive expectations and Friedman’s expectations-augmented Phillips Curve.) In all this, Friedman was simply echoing David Hume two centuries previously. Employment can be increased by monetary means only if increased inflation is unanticipated. But workers cannot be fooled for ever.

In developing this argument, Friedman introduced the idea of a unique ‘natural’ or ‘equilibrium’ rate of unemployment, which he defined as that rate which is consistent with stable prices (economists started talking about the ‘non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment’, or NAIRU). This embodies ‘the actual structural characteristics of the labour and commodity markets, including market imperfections, stochastic variability in demands and supplies, the cost of gathering information about job vacancies and labour availabilities, the costs of mobility, and so on’.24 Since the natural rate of unemployment is unknowable, it seemed reasonable to say it is the rate which establishes itself in the absence of unforeseen shocks, of which the chief is erratic monetary policy. If the equilibrium rate of unemployment is socially unacceptable, the remedy is not to inflate the money supply, but to undertake structural reforms to reduce ‘market imperfections’. As we can see, what was being reinstated was the neo-classical idea that an unimpeded market always produces a Walrasian full employment equilibrium. Friedman would provide the theoretical rationale for the ‘supply-side’ policies of Thatcher and Reagan in the 1980s and the ‘structural adjustment’ policies later advocated by the IMF as a condition for loans to needy countries.

Although monetary policy (and, even more so, fiscal policy, which operates with ‘long and variable lags’) is ruled out as a short-term regulator of business activity, monetary policy comes into its own as a stabilizer of prices. To combat inflation, governments should limit the rate of money growth to the rate of productivity growth. The sole object of monetary policy should be price stability, or at least a constant inflation rate. This was not to be done by discretionary monetary policy, which gave rise to ‘money illusion’, but by adopting a money rule such as that the money stock would increase at fixed rate, k per cent each year, this corresponding to the trend growth rate. The money rule would be set independently of the business cycle, but it would keep the economy ‘growing to trend’. If such a rule were to be adopted, fixed exchange rates would have to be jettisoned. Only a floating, market-determined, exchange rate would secure the necessary autonomy of monetary policy.

Thus, Friedman explains how the ‘first and most important lesson that history teaches about what monetary policy can do . . . is that monetary policy can prevent money itself from being a major source of economic disturbance’. ‘There is . . . a positive and important task for the monetary authority . . . to use its own powers so as to keep the machine in good working order.’ Monetary policy should

provide a stable background for the economy – keep the machine well oiled . . . Our economic system will work best when producers and consumers, employers and employees, can proceed with full confidence that the average level of prices will behave in a known way in the future – preferably that it will be highly stable.25

Friedman’s work clearly had huge anti-Keynesian policy implications. The four main ones are as follows:

1. Friedman restated the Quantity Theory of Money, the theory that prices (or nominal incomes) change proportionally with the quantity of money.

2. As a result of this, macro-policy can influence nominal, but not real, variables; i.e., the price level, but not the employment or output level.

3. Friedman argued that inflation was always and only a monetary phenomenon. It was the total money supply in the economy which determined the general price level; cost pressures were not independent sources of inflation, they had to be validated by an accommodating monetary policy in order to get away with a mark-up-based price-determination strategy.

4. Friedman’s permanent income hypothesis suggested that it is households’ average long-run income (permanent income) that is likely to determine total demand for consumer spending, rather than fluctuations in their current disposable income as suggested by the Keynesian consumption function.

As is clearer in retrospect, Friedman exploited to the full the paradox of government. The Keynesian revolution introduced the state as the stabilizer of a volatile system. How ironic, Friedman said, that the state should be the main destabilizer of the system!26 The ills which Friedman diagnosed were the result of state interference with natural market forces: the lesson first preached by economists in the eighteenth century.

At the time, many saw Friedman’s achievement as a vindication of the progressive nature of economics. His model had enabled him to predict stagflation, leaving the Keynesians flat-footed. The holes in his intellectual clothes became apparent only later. His ‘permanent income’ consumption function assumed that, as well as being improbably far-sighted, consumers had adequate savings and access to credit to cushion their consumption in downturns. His attack on Keynes’s speculative demand for money failed to recognize the role of money as a store of value. His restatement of the Quantity Theory of Money, despite its ‘proofs’, by no means disposed of the problem of causation which had dogged it since its inception. He assumed, rather than proved, that monetary policy alone could have prevented the Great Depression. His adaptive expectations theory failed to explain the acceleration in the rate of inflation between 1968 and 1974.

In essence, his restatement of the QTM, while more qualified than what he called ‘the simple theory’, reproduced its three main weaknesses: belief in the exogeneity of money; belief in a stable demand for money; and belief in the independence of monetary and real events. These were all to be tested to destruction when monetarism moved from the drawing board to policy.

Friedman’s weaknesses were overlooked because his theory served an ideological purpose. First, and foremost, it indicated that the inflation problem could be overcome without resort to controls over wages, prices and profits, and the implications of such controls for a free economy.27 Control of the money supply left the price system free. It just needed some experts in central banks with the right model of the economy.

Secondly, monetarism suggested a political economy argument for cutting down state spending. Keeping money well behaved would be easier the smaller the share of state spending in national income, because the more of national income that governments spent, the more likely they were to resort to financing their spending by printing money. The political right latched on to Friedman as a way of attacking the growing role of the state. Monetarism was to become the way to link popular dissatisfaction with high taxation, and the suspicion that the welfare state was being abused by ‘scroungers’, with the other great source of anxiety, inflation.28

Friedman’s wit and eloquence would never have overcome Samuelson’s self-assurance had not events conspired in his favour. It was the emergence and persistence of stagflation that turned conjecture into explanation, and explanation into experiment. Monetarism became fashionable because it was not the incumbent philosophy in a time of crisis; it had been exhaustively promoted by the neo-liberal thinktank complex and its influential supporters in and out of government; and its theory seemed to make sense of stagflation.

With inflation running at over 10 per cent in the developed world by the late 1970s, monetarism moved swiftly from the drawing board to active service. Following the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates in 1971–3, governments gave up interest rate targeting and credit controls and ‘chose to guide [their] policy for the economy as a whole by the behaviour of the quantity of money and by nothing else’.29 Unfortunately money refused to behave in the way Friedman said it should. ‘By the start of the 1990s economic policy had gone back to being guided by a range of indicators; and if central banks were given clear instructions they were in terms of inflation rather than money supply targets.’30 Short-term interest rates were the main inflation (or more broadly, aggregate demand) control mechanism: a monetary rather than fiscal version of Keynesian demand-management.31

Tim Congdon has usefully distinguished between American-style and British-style monetarism as it was tried out in the 1980s. Friedman believed that the monetary base – notes, coins and the cash reserves of commercial banks – was the best indicator of future changes in the total money stock, and consequently of the future rate of price increases. Total money stock included bank deposits. Empirical studies were held to demonstrate a ‘reasonably stable ratio between reserves to deposits over the long-run’32 (the money multiplier in a fractional reserve banking system). Since the quantity of cash was fully under central bank control, it was argued that ‘changes in the quantity of cash, reflecting central bank operations’ determined the level of bank deposits and, hence, of the money supply’.33 This is a straightforward QTM argument, exactly the same as Keynes’s in 1923. By varying the supply of bank reserves, the central bank can determine the total quantity of money in the economy and, therefore, the long-run price level.

The relationship between British-style monetarism and the QTM is less clear. British monetarism concentrated on the direct control of credit (‘broad money’) through short-term interest rates. With high inflation, real interest rates were negative. In the British view it was government borrowing to reduce unemployment which fuelled inflation, and therefore the deficit which government borrowing caused had to be eliminated. By 1974, Public Sector Net Borrowing stood at 9.6 per cent of GDP. Nigel Lawson, Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1983–9, promised in 1978 to ‘restore budget balance discipline’ as part of monetary control.

The two different versions of monetarism were tried out between 1979 and the early 1980s in the USA and Britain respectively, with pretty disastrous consequences. In 1979, Paul Volcker, the new Chairman of the US Federal Reserve Board, faced with an upsurge in inflation, switched Fed policy from targeting interest rates to targeting money. The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) ‘would seek to hold increases in the monetary base . . . to amounts just sufficient to meet monetary targets . . . recognising that such a procedure could result in wider fluctuations in the shortest term money market rates’.34 The Fed would sell government securities in the bond market. This would reduce the cash reserves of commercial banks, forcing them to raise interest rates. Influenced by the newly fashionable theory of rational expectation (see below, p. 194), Volcker hoped that this open-market policy would reduce inflationary expectations sufficiently to allow a rapid fall in the long-term bond rate, thus avoiding, or at least mitigating, the employment and output costs of bringing down the inflation rate.

It did not turn out like this. Inflation fell from 11 per cent to 4 per cent between 1979 and 1982, but at the cost of the worst recession since the Great Depression of the 1930s. Short-term interest rates shot up to 21 per cent, ruining not only many American businesses, but also developing countries, which now had to refinance their borrowed petro-dollars at a much higher rate of interest. Inflationary expectations, as measured by bond rates, remained above monetarist forecasts for much longer than Volcker had expected. In 1982, monetarism American-style was abandoned, but Volcker was hailed as the man who had broken the back of American inflation. Unemployment came down from 11 per cent in 1982 to 5 per cent in 1990. Ironically, the worst effects of the Volcker recession were offset by the huge budget deficits Ronald Reagan ran to finance his arms build-up against the Soviet Union.

The British experiment with broad money monetarism, which ran from 1980 to 1984, fared little better than the narrow money monetarism of the US. In the budget of 1980, Chancellor Geoffrey Howe presented the medium-term financial strategy (MTFS), which called for a phased reduction in the growth of the money stock, to be made possible by a phased reduction in the public sector borrowing as a share of GDP. The government expected that the announcement of the monetary targets would lower the inflationary expectations of wage-bargainers, enabling prices to come down with only a moderate increase in unemployment. It did not work this way. With the failure of the money supply figures to behave as required, Thatcher and Howe resorted to monetary and fiscal shock therapy. A bank rate of 17 per cent drove up the exchange rate, already strengthened by North Sea oil revenues. Superimposed on this was a savagely deflationary budget in 1981, which took £4 billion out of the economy when unemployment was already rising – the first time since 1931 when, with output rapidly falling, budgetary policy was tightened. Its message was clear: Keynesianism would not be reactivated, whatever the unemployment cost. This cost was heavy. Between 1980 and 1982 unemployment rose from 5 per cent to 10 per cent, as bad as in the 1920s, and went on creeping up until 1986, hitting 3 million. In a letter to The Times of 30 March 1981, 364 economists, including the future Governor of the Bank of England, Mervyn King, predicted that government policy would ‘deepen the depression, erode the industrial base of our economy and threaten its social and political stability’. However, almost before the ink was dry on the letter, economic recovery started, with output growing by 3.3 per cent a year on average over the following six years. At the same time, inflation fell from 17.8 to 4.3 per cent. A fall in short-term interest rates to 5 per cent by mid-1980s led to a housing boom.

In both cases, the strategy of credible gradual disinflation broke down, with inflation being reversed by shock therapy which imposed a huge cost on output and employment. Analysts pointed to the instability of the demand for money. Both the 1970s and 1980s saw continued enormous swings in velocity, which made money growth a poor predictor of future prices and income. Charles Goodhart enunciated his famous ‘law’ that any established relationship between money and prices breaks down as soon as the attempt is made to exploit it for control purposes. But the flaw lay with the new monetary theory itself: there was never sufficient belief in the pronouncements of the monetary authorities to make disinflation a relatively painless exercise. In an interesting retrospective piece, David Laidler partly retracts his earlier support for the medium-term financial strategy. He argues that when transitioning to a lower average rate of inflation and nominal interest rates, the demand for money will rise (the inflation tax on holding money is lower), so money growth should be slowed more gradually. In his view, the failure to recognize this was responsible for the depth of the 1980s recession.35 By contrast, Patrick Minford argues that the gradual disinflation policy would have been too slow to be credible: it was the ‘sharp monetary squeeze’ (i.e. on ‘narrow’ money) imposed by the government in 1980 and 1981 which broke the back of inflation.36

The policy failures of monetarism led the Fed and the Bank of England to abandon the attempt directly to control monetary aggregates. Inflation targeting became the default position. Its great advantage was that it bypassed the interminable debates about whether money was exogenous or endogenous, whether one should try to control narrow money or broad money, what the transmission mechanism was from money to prices, etc. All one had to do was deploy old-fashioned bank rate policy plus new-fangled management of expectations. In 1993, Alan Greenspan, Volcker’s successor as Fed Chairman, announced that all monetary targets were to be dropped. The Fed then used openmarket operations to influence the federal funds rate, announcing a desired target for inflation and instituting rule-type behaviours to provide consistent signals to markets. (This became standard practice until 2012, when it adopted an explicit inflation target under Ben Bernanke.)37 The European Central Bank, established in 1997, was also given an inflation target, to be achieved by varying short-term interest rates. In Britain, targeting of money was discontinued in 1985. The British government briefly sought to discipline its unruly economy, first by shadowing the deutschmark, then by making sterling a member of the European Monetary System, but after a speculative attack on the over-valued pound forced it out of the Exchange Rate Mechanism in 1992, it followed the American lead. Initially, the inflation target was set in the range of 1–4 per cent. In 1997, the incoming Labour government, fearing that this was too loose to anchor inflationary expectations properly, especially as politicians still controlled interest rate setting, transferred control of monetary policy to the Bank of England, giving it a 2.5 per cent Retail Price Index inflation target (later reduced to the 2 per cent Consumer Price Index target we have today).

The monetarist experiment was over. What survived were the two main reasons for setting up independent central banks: to get as much economic policy as possible out of the hands of vote-seeking politicians, and to find an effective way of controlling inflation. These coalesced in the idea that interest rate policy should be taken out of the hands of governments. By 2005, thirty ‘independent’ central banks, led by New Zealand’s, were ‘targeting’ inflation. (The New Zealand plan had been to tie the salary of the central bank’s governor, Donald Brash, to the bank’s inflation performance, but this proved impracticable.)

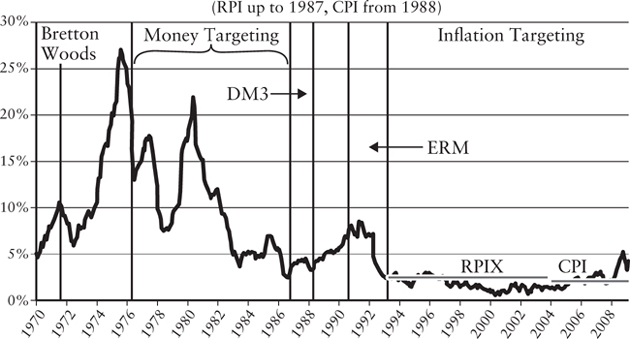

Figure 16 shows the start of money targeting in the UK in 1976. Inflation remained high and variable: it averaged over 12 per cent a year in the 1970s and nearly 6 per cent a year in the 1980s. The inflation record improved dramatically when inflation targeting was announced in 1992. The same pattern was seen the world over.

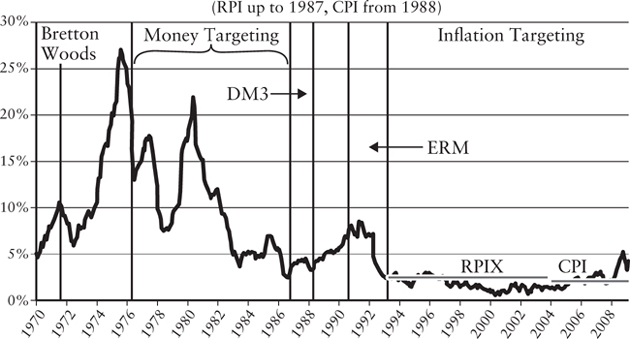

Was it inflation targeting that ‘conquered’ inflation? Much depends on the weight one attaches to the fluctuating price of energy over the period 1973 to 1983.

Figure 16. UK monetary policy and inflation38

Figure 17. Oil prices and UK CPI ination39

The two large spikes in oil prices in 1973–4 and 1980–82 were followed by peaks of inflation. The fall in the oil price in the mid-1970s and the early 1980s were followed closely by falls in the inflation rate. Again we have a correlation, but the causal direction is debatable. In consequence, the question of how big an influence monetary policy has on the inflation rate is no further to being decisively answered now than it was when economists and bankers debated the causes of inflation during the Napoleonic wars.

The fact that inflation in industrial countries came down worldwide in the 1990s, irrespective of the type of counterinflation policy chosen, and has never again reached the heights of the 1970s, strongly suggests that changes in the structure of the world economy, rather than deliberate changes in policy, played the key part in the result. If there is no inflationary pressure it is child’s play for a central banker to keep inflation low. On the other hand, if there is a tendency towards deflation, there is little monetary policy can do on its own to reverse it. This lesson had to be learned all over again in the years following the collapse of 2008–9.

The interesting question is whether inflation could have been brought down at lower cost in unemployment. The answer is surely yes, with a better mix of policies than were politically available in countries like Britain, one of the worst hit by both inflation and unemployment. As the Treasury had pointed out in 1944, and as Kaldor had realized in the 1960s, continuous full employment required the right allocation of supply as well as the right level of demand. The simple inversion of Say’s Law – ‘demand creates its own supply’ – proved to be as insufficient as its original.

The fiscal consequence of monetarism was to remove the budget as a tool of short-run demand-management. This removed the Keynesian rationale for budget deficits.

However, the Reagan Administration was much more relaxed about deficits than its Thatcherite colleagues in Britain. On the one hand, following the Friedman doctrine, the US Treasury saw no causal connection between public deficits and inflation. The second reason was much more important: Reagan had been elected on a programme of cutting taxes and increasing defence spending. The enactment of both, together with the Volcker recession, caused the deficit to rise from 2.8 per cent of GDP in 1980 to 6.3 per cent in 1983. The tax cuts and increased military spending amounted to a big Keynesian demand boost. But in the post-Keynesian world this ‘Keynesian effect’ could not be acknowledged. Instead, the large deficits were justified on ‘supply-side’ grounds.

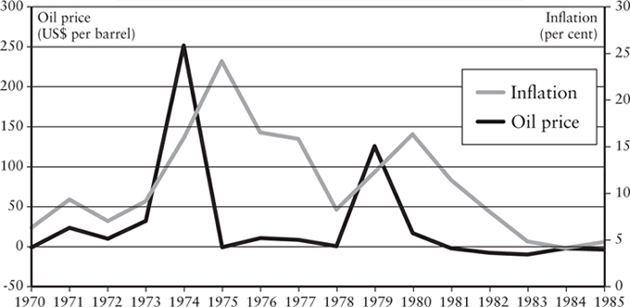

Figure 18. The Laffer curve

The famous Laffer curve, supposedly drawn on a napkin by the economist Arthur Laffer at a boozy dinner in 1974, suggested that tax reductions would have positive supply-side effects. The logic was simple. Government revenue must be zero at a tax rate of 0 per cent, and also at a rate of 100 per cent, since no one would then bother to work. There must, however, be an intermediate rate at which revenue is maximized. The supply-siders’ big idea was that, within a range, if taxes are reduced, people will work harder, productivity will go up, and the economy will grow faster. That people might choose to cash in their higher post-tax incomes in the form of leisure, or work harder to maintain their accustomed living standards if their taxes went up, was alien to the mentality of the supply-side enthusiasts. Their simplistic story, devoid of any empirical evidence, fed the illusion that tax cuts would be self-financing.40 We see the same story being reenacted under Donald Trump.

The British Treasury never bought into Laffer-type arguments; additionally, British anti-inflationary policy was much more closely linked to public spending cuts. Geoffrey Howe’s 1981 budget marked the arrival in Britain of what later became known as ‘expansionary fiscal contraction’. This claims that fiscal consolidation, while bearing down on inflation, will produce recovery by lowering interest rates and improving the profit expectations of the private sector. The roots of this über-Austrian idea lay in Italy – at the School of Economics at Bocconi University of Milan founded by the former President of the Italian Republic Luigi Einaudi. Einaudi, who had argued for constitutional rules banning fiscal deficits, came to influence a large cohort of Bocconi students who, in turn, rose to the heights of the global economics profession: Alberto Alesina, Silvia Ardagna, Guido Tabellini and Roberto Perotti.41 Thirty years after Howe’s 1981 budget, the works of these Bocconi School economists provided the academic justification for the sweeping austerity measures adopted by European governments after the collapse of 2008–9.

In Britain, Nigel Lawson, Howe’s successor as Chancellor from 1983 to 1989, was the intellectual force behind the destruction of the last vestiges of the Keynesian fiscal constitution. In 1980, he wrote that ‘Monetarism, after all, is really rather obvious. It is Keynesianism, which seems to stand everything on its head, which is the difficult and esoteric doctrine.’42 One of the assumptions of the old QTM inherited by the new monetarism was that, with stable prices, the real economy would be cyclically stable at its ‘natural’ rate of unemployment. In his Mais Lecture of 1984, Nigel Lawson said: ‘It is the conquest of inflation, and not the pursuit of growth and employment, which . . . should be the objective of macroeconomic policy. And it is the creation of conditions conducive to growth and employment, and not the suppression of [inflation] which . . . should be the objective of microeconomic policy.’ Reduction in the ‘natural’ rate of unemployment required not boosting demand, but labour market reforms to boost supply.43

Like the Victorians, Lawson believed in annually balanced budgets. He rejected the idea of a capital budget financed by borrowing, or indeed any relevant distinction between capital and current budgeting. In his memoirs published in 1992, Lawson writes:

Behind this criticism [that his Treasury had conflated current and capital expenditure] is a lingering belief that capital spending is either superior to current spending, or at least safer to finance from borrowing. This really will not do. The current/capital distinction does not have the same meaning in the public as in the private sector.44

Hence his objective was zero borrowing.45A large part of the capital budget was abolished by privatizing state assets. In addition, employment subsidies were ended. Between the 1960s and 1980s, public investment fell from 7 per cent to below 1 per cent of GDP, where it remained for most of the 1990s. There was an attempt to rein in social spending. In 1988, in the wake of a boom and large-scale privatizations, Lawson declared that ‘in this Budget, I have reaffirmed the prudent policies which have brought us unprecedented economic strength . . . I have balanced the Budget.’46 He not only balanced his budget, he was able to cut taxes and repay debt: the epitome of a successful Victorian Chancellor. But this was a unique achievement in eighteen years of Conservative rule, and was not repeated for another ten years.

The effect of the Lawson counterrevolution was to denude fiscal policy of macroeconomic significance. Macroeconomic stabilization was left to monetary policy just as it had been at the beginning of the century. In order to meet its money supply and, later, inflation targets, the central bank had to tighten monetary policy if the government expanded its deficit. This robbed the latter of any short-term stimulative effect. Only a year after the triumphant 1988 budget, however, the Conservatives had to soften their tough year-on-year balancing objective. As the Lawson boom ended in bust, and with it a big increase in the budget deficit, the aim switched to ‘balancing the budget over the medium term’. We have reached the era of Gordon Brown and his fiscal rules.

Friedmanism was just the start of a wholesale unravelling of the Keynesian system of thought. Monetarism was soon refined by the ‘rational expectations hypothesis’ (REH). The REH was the analytic core of what came to be called ‘the new classical macroeconomics’. This built on the deceptively simple, common-sense idea, shared by Keynes and Friedman, that people’s beliefs about the world influence their behaviour. It was economists’ task to provide economic agents with true beliefs – true models of the economy – to help them make the best of their situation. Keynes wrote the General Theory to refute the Treasury View; Friedman restated the Quantity Theory of Money to falsify the Keynesian view. Both ‘models’ of reality were intended to change people’s beliefs about how economies worked and therefore their expectations concerning the effects of policy. Now it was the turn of Robert Lucas, a former student, then colleague, of Friedman’s at Chicago University. Lucas brought rational expectations into macroeconomics in 1972. He was a logical extremist. His aim was remove what he saw as a conceptual flaw – though others might see it as a lingering sense of realism – in Friedman’s theory of adaptive expectations.47

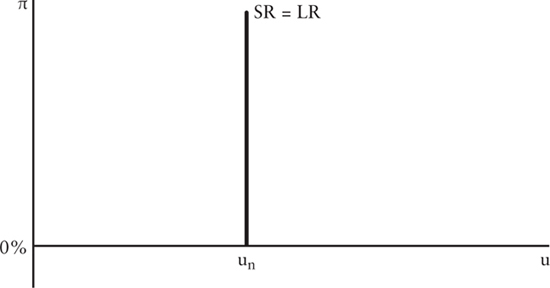

Lucas accepted Friedman’s argument that policymakers’ attempt to exploit the Phillips Curve trade-off between inflation and unemployment caused the trade-off to disappear. This is because it led to changes in the behaviour of the relevant economic agents. Friedman has agents learning from, and adapting their behaviour to, changing market signals, but with an inevitable lag because it takes time to change expectations and the contracts based on them. Lucas simply abolished the lag. Rational agents should be able to process all available information efficiently in forming expectations. The Phillips Curve is vertical in the short-run as well as in the long-run, as agents instantaneously adapt their expectations in accordance with ‘the model’.

Lucas carried this thought to its logical conclusion, by arguing that all policy conclusions drawn from large-scale econometric models of the type favoured by Keynesians were useless for forecasting purposes, because economic time-series are non-linear.48 Persistent attempts to exploit correlations for control purposes lead to behavioural changes. This was an attack on the very idea of macroeconomic policy: optimization by individuals should be the only theoretical foundation for macroeconomic models; and transparent rules the only foundation for economic policy. This second formula sought to return monetary policy to the rule-bound era of the gold standard. It was only if monetary policy was completely predictable that it would have no real effects. (See Appendix 7.2, p. 205, for a more detailed account of rational expectations theory.)

The rational expectations revolution led to Real Business Cycle (RBC) theory. RBC theory accepted that economic fluctuations can be caused by supply (for example, technological) shocks as well as monetary shocks, but sought to incorporate short-run dynamics into a properly micro-founded inter-temporal general equilibrium framework. Business fluctuations were the ‘efficient’ results of optimizing agents responding to supply-side ‘shocks’. The general purport of this class of models was that economies are always at full employment, since fluctuations in output are fluctuations in Friedman’s equilibrium rate of unemployment, not deviations from it.49 Of course, there may be unemployment, but this is voluntary. The reductio ad absurdum of this view was that an economy experiencing 50 per cent unemployment could be at full employment! Lucas is a good example of the flaw which Keynes detected in Hayek: ‘how, starting with a mistake, a remorseless logician can end in Bedlam’.50 The mistake was the theory of rational expectations itself. By 2003, Lucas was confidently claiming that ‘the central problem of depression-prevention has been solved for all practical purposes’, which invites the retort that one can always prevent depression by denying its existence.51

The idea that fully rational and informed agents were choosing to remain unemployed for year after year was too much for all converts to the REH. The long stagnation of the 1980s led to ‘New Keynesianism’, the attempt to incorporate ‘Keynesian’ features into micro-founded models by reviving the old idea that ‘frictions’ of various kinds can cause deviations from an optimal level of output.

New Keynesians were able to explain sticky prices in a rational expectations framework. With imperfect information and imperfect competition, firms and job-seekers may reach inferior bargaining outcomes. The so-called Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium (DSGE) models of the 1990s embedded into the REH and RBC structure a number of nominal rigidities and market imperfections.52 Most common were price and wage rigidities and various forms of consumer myopia. These allowed for temporary demand shortages, on which central bank policy could have a significant short-run impact. This was the basis of the ‘New Consensus’. New Keynesians accepted that there was no long-run trade-off between price stability and employment, but claimed that government could influence employment in the short-run.

There has been a further softening of the hard edge of the REH. The earliest versions equated rationality with prodigious capacity to acquire and process information. Behavioural economists pointed out that this was not a necessary condition of rational behaviour. Faced with ‘cognitive overload’ people rely on mental short-cuts, or heuristics (rules of thumb). Examples include anchoring (relying on the first piece of information), availability (prominent examples), and familiarity (extrapolating from past situations). These were reasonable ways of forming expectations. ‘Nudging’ expectations in the desired direction became the chief instrument in the central banks’ tool kit. Simon Wren Lewis put a New Keynesian gloss on this policy procedure, arguing that ‘implicit or explicit inflation targeting by independent central banks . . . reflected an understanding of the importance of rational expectations. If a central bank had a clear inflation objective, and established a reputation in achieving it, that would anchor expectations and reduce the impact of shocks on the macroeconomy.’53

How far it makes sense to think of heuristics as reasonable abbreviations of all available information is doubtful. There is more than a whiff of magical thinking involved in the belief that thoughts by themselves can bring about desired effects in the real world. Keynes, too, believed that in face of uncertainty people fell back on ‘conventions’ or ‘rules of thumb’. But he did not believe that these were, in general, short-cuts to calculation, because he thought that in many situations no calculation was possible. He thought that an economy built on pretence to knowledge was liable to sudden collapses when the pretence was exposed; and confidence, once deceived, could not readily be restored.

In accepting the REH and RBC theory as the framework for macroeconomic analysis, the New Keynesians surrendered Keynes’s own emphasis on uncertainty – there was no uncertainty in these models, only contingently imperfect information within known probability distributions – for precious policy space. The assumption that markets take time to clear justified limited government intervention, since it meant that the actual rate of unemployment can remain above its equilibrium rate for some time. This was contrary to Keynes who argued that there is no ‘natural’ rate of unemployment in a monetary economy.

The theoretical compromise between the New Classical and New Keynesian economists influenced central bank policy. Thus, though the mainstream policy models from the 1980s onwards assumed rational expectations, they also allowed some degree of wage and price stickiness, and that meant there was still a short-term trade-off between inflation and output facing policymakers. In practice, the pre-crash central bank models of the 2000s were a compromise between adaptive and rational expectations. Rational expectations chiefly came to influence policy in the form of automatic ‘reaction rules’ to anchor expectations; adaptive expectations in making the inflation rate a medium-term target.54 This was a pragmatic compromise, leaving room for attention to output: the rules, in economics-speak, were ‘state contingent’.

Congdon has called this control system ‘output-gap monetarism’;55 or one could call it ‘constrained discretion’. The crucial point, though, is that the policy space was much too small. It failed to take into account the possibility of a large-scale collapse of the financial system.

Adjustment to ‘real’ shocks was increasingly sought, not in macropolicy, but in varieties of supply-side policies designed to improve the working of markets. As Stedman Jones notes for Britain:

The major differences, and the real departure in economic terms, between the Callaghan government and the Conservatives lay in [the latter’s] radicalization of microeconomic policy through various market-based supply-side reforms and their importation of market mechanisms into public service provision, something the Labour Party continued and deepened after 1997.56

The new orthodoxy’s structural reform ideas spread across the world in the form of the ‘Washington consensus’ that, through the IMF and the World Bank, made the receipt of financial support conditional on the deregulation of financial sectors, the privatization of state-owned enterprises, the liberalization of markets and fiscal discipline.

The revolution in theory initiated by Friedman and Lucas ran in parallel with another theoretical enterprise particularly relevant to policy, known as the ‘economics of politics’. Its main thrust was to emphasize the importance of the private incentives facing politicians and bureaucrats. The Keynesian-social democratic state was modelled as a private interest masquerading as guardian of the public interest. This was back to Adam Smith. Democracy, in theory a check on political choice, was misguided, easily manipulable and incoherent. (Voters wanted more welfare, but were not prepared to pay higher taxes.)

James Buchanan’s ‘public choice’ theory undermined the ‘benevolent despot’ view of government that had implicitly underpinned much Keynesian advocacy of state intervention. Politicians, said the public choice school, were more interested in maximizing votes than stabilizing economies. By 1976, Assar Lindbeck was writing that

a pessimist, or a cynic might . . . be tempted to say that the most severe difficulties of economic policy are embedded in the political rather than in the economic system . . . Consequently, the best thing to do would be to avoid discretionary policies altogether, rather than trying to make the interventions more sophisticated.57

The theory of ‘government failure’ thus provided a powerful argument for a limited state, in which politicians were restrained by fiscal rules, and policy placed in the hands of independent central banks. It shaped the European institutions adopted by the 1992 Maastricht Treaty, with control of inflation assigned to an independent European Central Bank, and a ‘Stability and Growth Pact’ to set a cap on government deficits.

Finally, and less directly, analysis of economic growth by historians such as Douglass North emphasized the importance of the right individual incentives for economic development, including private property rights and moral codes. This insight started to yield very different policy prescriptions from the concentration on boosting aggregate saving and investment totals fashionable in the heyday of Keynesian development economics. The shift was quite quick. Walt Rostow’s The Stages of Economic Growth (1961), the bible of 1960s’ ‘growthmanship’, and North and Thomas’s ‘An Economic Theory of Growth in the Western World’ (1970) already inhabited different mental universes.58

Public choice theory is simply rational expectations theory applied to government. It takes from REH the methodology of modelling public policies as the solution to individual maximization problems.59 In doing so, it revives the original inspiration of scientific economics, which juxtaposed the efficiency of markets with the corruption of the Prince.

The main features of what Michael Woodford called the ‘new synthesis’ were as follows:

1. Economists accept the crucial importance of expectations in determining the impact of alternative policies. This is a legacy of Keynes. But Keynes’s distinction between uncertainty and risk was abolished. Uncertain expectations can be reduced to rational expectations, based on the presumption that current probability distributions are valid for an indefinite future. Equipped with constantly updated information, economic agents adjust instantly and efficiently to all external shocks. The New Keynesian economists inhabited this same universe of rational expectations, but, by ‘relaxing the assumptions’, they allowed for sluggish adjustment to shocks. Keynes’s insights into the psychology of financial markets, the instability of investment, and the role of money as a store of value were irrelevant.

2. While the simple aggregate equations of Keynes’s macroeconomic model (IS/LM) continued to be taught, there was a return to neo-classical standards of method. No longer was it considered acceptable to posit ad hoc supply and demand functions. Macroeconomics should best be seen as an application of microeconomics, in the sense that macroeconomic models should be based on optimization by firms and individuals. This is contrary to Keynes, who believed that individual behaviour is shaped by aggregate psychological and social data.

3. Mainstream economics is now based on supply not demand. It reasserted a version of Say’s Law. Thus both the New Classicals and the New Keynesians believed that the long-run growth of real GDP depends on an increase in the supply of factor inputs and technological progress. Technological progress is assumed to be independent of the demand for technology. Further, many economists only accepted sticky contracts as contingent, not inescapable. The ‘supply side’ school of economics, by aiming to remove market imperfections, looked forward to a world of complete markets and instantly renegotiable contracts. Deregulation of financial markets, a key element in this agenda, proved to be its Achilles heel.

4. Following Friedman, mainstream economics reasserted the primacy of monetary policy. The disinflation of the 1980s and 1990s proved beyond doubt, they claimed, that central banks could control inflation. Provided money is kept ‘in order’, economies would stick to their long-run equilibrium growth path. This view reasserted the optimism of the monetary reformers of the 1920s, who sought in monetary policy a therapy for the fluctuations of capitalist market economies.

5. In modelling economies, New Classical economists were not fazed by the unrealism of their assumptions; indeed, they regarded this as a strength of their models. The important thing was that their models should be logically coherent. This was contrary to Keynes, who insisted on realism of assumptions. Nevertheless, the new synthesis insisted that policy should be based on econometrically valid structural models. Hence the many attempts, by methods of ‘simulation’, to discover fits between model predictions and aggregate time series.

6. In contrast to the Keynesian consensus during the ‘golden age’, it was widely thought that governments should not now try to ‘fine tune’ economies. Instead, stabilization policy should merely aim to assist, or give time for, the market’s self-correcting capabilities, chiefly by keeping prices stable and relying on automatic fiscal stabilizers.

7. Whereas in the 1950s and 1960s stabilization was seen mainly as a control theory problem, it now took into account strategic interaction between authorities and agents whose expectations the authorities needed to ‘manage’ by means of clear rules. This follows the normative prescription that governments should aim to provide agents with a consistent model of the economy.60

The cumulative effect of these theoretical developments was to narrow the scope of macroeconomic policy and change its explicit aim. Provided money was ‘controlled’, economies would be stable, for reasons given by Wicksell – but denied by Keynes – namely, that there existed a ‘natural’ rate of interest that balanced the saving decisions of consumers and the investment decisions of producers. Thus a monetary policy which was confidently expected to keep a low, constant inflation rate – that is, would prevent money from deceiving market participants about the real value of their contracts – was the key and, in effect, the only requirement for maintenance of an optimum equilibrium.

With acceptance of the ‘natural rate’ doctrine, much of macro-policy’s early unemployment-reducing function was assigned to micro-policy or ‘structural’ reforms aimed at galvanizing individual incentives to wealth production. This in turn tended to re-establish the so-called classical dichotomy between money and the ‘real world’, and amounted to the theoretical abolition of the Keynesian revolution. Differences between the New Classicals and New Keynesians certainly remained, but they were political rather than theoretical.

The way in which Keynes’s General Theory was transmuted into the New Classical–New Keynesian synthesis illustrates why there have been so few, if any, paradigm shifts in economics comparable to the overthrow of Ptolemaic by Copernican astronomy. Scientific economics is essentially a synthesizing discipline. It hoards its accumulated knowledge, spewing out any that is obviously inconsistent with it, and assimilating innovations too important to be ignored. The cases we have considered exhibit a common pattern: the pure essence of the theory is diluted for policy purposes, leaving the core theoretical structure intact. In the 1940s and 1950s Keynesian policy was grafted on to neo-classical theory. In the 1980s and 1990s, New Keynesian policy was grafted on to New Classical theory. What has remained intact throughout is the theory of the optimizing agent. Indeed he/she has now been equipped with rational expectations, further narrowing the Keynesian policy space allowed by the earlier generation of synthesizers.

One cannot survey the story of the unravelling of the Keynesian revolution without being struck by the close link between economic theory and political ideology. The Keynesian revolution created a space for government intervention in the economy. The reaction against it consisted first in minimizing the theoretical justification for that space, then in emphasizing the flaws in Keynesian policy, and finally in trying to abolish the space altogether. Despite the flaws in Keynes’s own theory, and the even greater ones in those of Keynesian economists of the Samuelson generation, one cannot avoid the strong impression that the whole unravelling was driven by ideological hostility to government per se, which, as we have seen, has its roots in the original mindset of economics: a return to the roots after a long deviation.

The period of the Great Moderation, which supposedly ran from the early 1990s, when the transition to the new regime was accomplished, to the onset of the crisis in 2008, was believed to vindicate the new system of macro-management. Disconfirming events like the East Asian financial crisis of 1997–8, and the collapse of the dotcom bubble in 2001, were regarded as ‘teething problems’, which would be overcome by a continually updated learning process, making financial markets ever more efficient. True, the average OECD rate of unemployment in the new ‘normal’ was more than double what it had been in the ‘old’ normal (7 per cent between 1992 and 2007, as opposed to 3 per cent between 1959 and 1975), but this was seen as a legacy of bad labour-market practices which would soon yield to further labour-market reforms. By 2006, it was confidently believed that efficient markets were close to being fully established. Almost no one expected things to go seriously wrong.

As Robert Lucas remarked in 1980: ‘At research seminars, people don’t take Keynesian theorising seriously any more – the audience starts to whisper and giggle to one another.’61 But these giggling economics students became architects of the policy that led to the great crash of 2008.

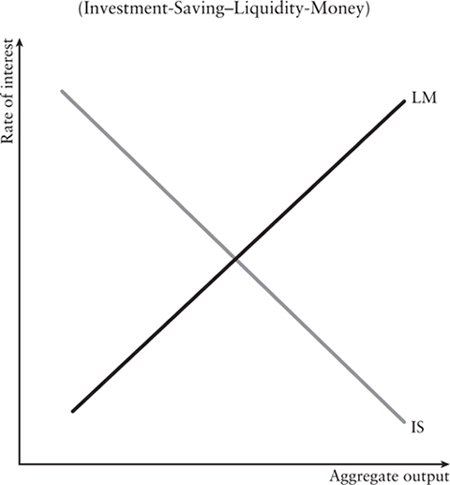

The IS curve shows the locus of combinations of interest rates and output such that savings and investment are in equilibrium. It is downward sloping because, as interest rates fall, investment becomes more attractive. This increases output, and some of this output will be saved, generating a new investment-savings equilibrium at a lower interest rate.

The LM curve shows the locus of combinations of interest rates and output such that the market for money is in equilibrium, i.e. the demand for money equals the supply of money. As output increases on the horizontal axis, the demand for money increases. In order for the money market to remain in equilibrium, the price of money (i.e. the interest rate) has to increase in order for supply to meet demand. This is why the curve slopes upwards.

Figure 19. IS-LM model (Investment-Saving–Liquidity-Money)

The intersection of these curves shows the unique, equilibrium level of income and interest rates for a given quantity of money, when the markets for both goods/services and money are in balance.

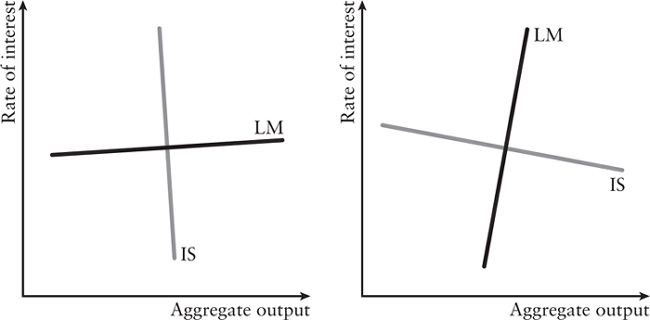

The IS/LM diagrams in Figure 20 show the Keynesian (left-hand graph) and the neo-classical (right-hand graph) views of the economy. In the Keynesian account, investment is insensitive to changes in the interest rate, instead being determined by confidence, and money demand is very variable, implying a steep IS curve and a shallow LM curve. In the neo-classical account, investment is very sensitive to changes in the interest rate, whereas money demand is relatively stable, giving us the converse slopes.

Expansionary fiscal policy is shown by a rightwards shift in the IS curve, whereas an expansion in the money supply is shown by a rightwards shift in the LM curve, reflecting the difference between interaction in money and goods/services markets. As we can see, a rightwards shift in the IS curve will restore large amounts of output in the Keynesian case, but will have limited impact in the neoclassical case. The reverse is true for shifts in the LM curve.

Figure 20. Keynesian and neo-classical views of the economy Aggregate output

The Philips Curve failed altogether to distinguish between nominal wages and real wages. In the Phillips Curve world, all agents anticipated that nominal prices would be stable, whatever happened to actual prices and wages. Take the following simple version of adaptive expectations:

Et[Pt+1] = [[Pt]] + λ (Pt-Et-1[Pt]);0 < λ <1

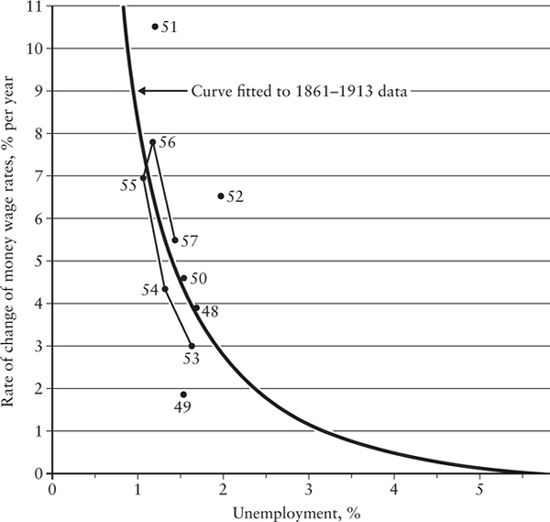

Figure 21. The Phillips Curve, 1948–195762

This says that agents learn from their past mistakes: Et[Pt+1] shows people’s current expectations (in period t) for inflation in the next period (t+ 1); inflation in the current period is shown by Pt; and Et−1[Pt] is what people expected current inflation to be in the last period (t−1).

So current expectations of future inflation reflect past expectations and an ‘error-adjustment’ term, in which current expectations are raised (or lowered) according to the gap between actual inflation and previous expectations. The higher λ is, the more people take their previous mistakes into account.

It should be clear that the implication of adaptive expectations is that the economy can be stimulated only in the short-run, or sometimes only in the very short-run. Monetary policy essentially can stimulate the economy – by lowering interest rates or pushing the unemployment rate below its ‘natural’ rate – only in the time that it takes for people’s expectations to adjust. The temporary trade-off comes from unanticipated inflation.

This can also be seen in terms of the ‘money illusion’ which stimulates the economy through making people want to spend more, but that only works in the short-run. Under the money illusion, people feel richer when, for example, the monetary authority pumps extra money into the economy, but this is only because they fail to realize that prices will rise proportionately. People are essentially taking changes in nominal variables (the money supply) as real, although purchasing power has stayed constant. The money illusion disappears in the medium- to long-run as agents adjust their expectations in response to observing increases in price.

All of this is to say that one cannot profit from the inflation–output trade-off shown by the original Phillips Curve in the medium–long-run, as the Curve itself shifts due to the level of inflation rising and people adjusting their expectations upward.

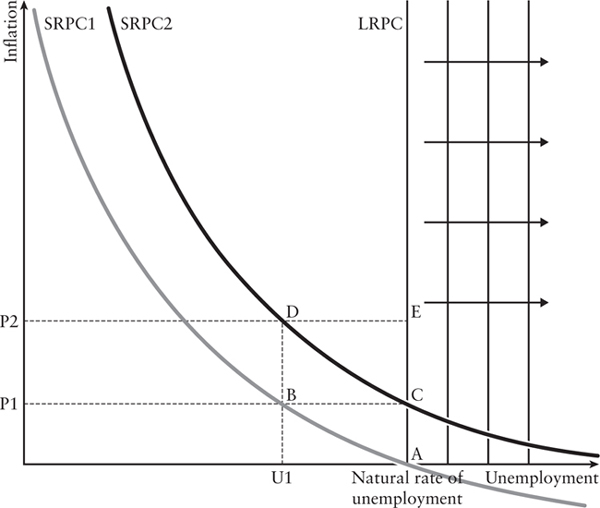

Friedman’s theory of adaptive expectations gives the ‘expectationsaugmented Phillips Curve’ (Figure 22).

The economy starts at point A, at the natural rate of unemployment (see below) where demand is equal to the economy’s productive capacity. The government sees that it is on a given short-run Phillips Curve (SRPC1) and wants to take advantage of its inflation–unemployment trade-off, so it stimulates the economy to reduce unemployment to rate U1. At this level of unemployment, workers demand higher wages and this pushes general price inflation up to rate P1. In the short-run, the economy is at point B.

Figure 22. Expectations-augmented Phillips Curve

Workers realize that this price rise has eroded their wage increase in real terms, and so labour supply falls, bringing employment and output back to their ‘natural’ rates. But now, given adaptive expectations, agents expect inflation of P1, and this becomes built into their wage demands. The economy thus moves to point C. The short-run Phillips Curve has shifted outwards, to SRPC2, reflecting a worsening of the inflation– output trade-off.* If the government tries a similar tactic again, the economy will move to point D and then E in the same fashion, but at a faster pace as workers have learned from their previous experience. This further pushes the short-run Phillips Curve to the right.

In the long-run, expansionist monetary policy leads directly to higher inflation, with no effect on unemployment. The long-run Phillips Curve (LRPC) is completely vertical. There is no trade-off between inflation and employment at all. In practice, this means that intervention is undesirable as it would just lead to more inflation.

Thus Friedman restated the pre-Keynesian idea that there is a unique equilibrium rate of unemployment, the ‘natural’ rate, towards which the economy always reverts. Furthermore, insofar as price instability erodes the productive capacity of the economy – for example, decreasing investment – the long-run Phillips Curve will shift rightwards as the natural rate of unemployment rises.

‘Rational expectations’ first appeared in the economic theory literature in a famous article by J. Muth in 1961, but only filtered through to policy discussion in the early 1970s with the work of Robert Lucas and Thomas Sargent on business cycles, and Eugene Fama on financial markets.

As defined by Haberler, rational expectations is the ‘radical wing of monetarism . . . best known for the startling policy conclusions . . . that macroeconomic policies, both monetary and fiscal, are ineffective, even in the short-run’,63 because agents adapt their expectations immediately.

Thus the rational expectations revolution started with a critique of adaptive expectations. Friedman’s theory of adaptive expectations relied on the gradual adjustment of expectations to the experienced behaviour of a variable, so there is an exploitable trade-off between employment and inflation in the short-run. According to Lucas, however, agents will adjust their expectations immediately. This is because our knowledge includes not just what we have experienced, but current pronouncements of public authorities and theoretical knowledge of aggregate relationships too. Indeed, the rational expectations hypothesis (REH) says that agents optimally utilize all available information about the economy and policy to construct their expectations.

For instance, if the Minister of Finance announces that he will increase the money supply by 10 per cent a year to stimulate employment, knowledge of the model of the economy and of the QTM, in particular, tells us that prices will increase proportionately. So it makes sense to expect inflation to be 10 per cent a year. You do not have to wait for prices to start increasing to revise your expectations. In other words, it is rational to expect inflation to be 10 per cent a year; this is the theory of rational expectations. In this example, rational expectations is defined as belief in the QTM. Adaptive behaviour is a description of irrational behaviour, if agents know what to expect already but do not change their behaviour.

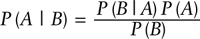

In other instances, agents adjust their expectations through repeated application of Bayes’s theorem, a method of statistical inference:

For instance, suppose that agents are uncertain about other agents’ risk aversion. Then it is assumed that they still ‘understand what is happening well enough to form rational expectations based on their prior probability assessments of the things they are uncertain about, and the information they observe as time progresses’.64 In applying Bayes’s law, agents turn their subjective bets into objective probability distributions.

Agents are able to learn and adjust their expectations so quickly and efficiently that the REH implies that outcomes will not differ systematically from what people expect them to be. If we take the price level P, for instance, we can write:

P = E[P] + ∈