‘In my judgment, the big challenge to monetary policy before the crisis was a serious mis-pricing in long-term interest and exchange rates and the imbalances that resulted.’

Mervyn King, 20121

‘If a country consumes more than it produces, it must import more than it exports. That’s not a rip-off; that’s arithmetic.’ George P. Shultz and Martin Feldstein, Washington Post,

5 May 2017

How far did global imbalances contribute to the crisis? By global imbalances we mean persistent surpluses and deficits in countries’ current accounts. A pseudo-Keynesian answer would be that the current account surpluses of China and the Middle East produced a global ‘savings glut’, which could only be liquidated by a decline in the world economy. But this does not explain the weakness of investment performance in the capital-importing countries. In Keynesian theory, ‘excess saving’ is the result of under-investment, not an independent factor. So it is the weakness in the inducement to invest which needs explaining.

The other problem with the ‘global imbalances’ explanation of the collapse of 2007–8 is that it is not clear how it relates to the speculative boom and bust in the housing market.

The discussion is bedevilled by tautologies and identities, so that it is difficult to work out what is causing what.

A country’s balance of payments is simply that part of the national accounts that shows payments in any year to and from foreigners. Its current account comprises the balance of trade in physical goods and (mostly) financial services, and other income transfers; its capital account records exchanges of assets and liabilities.

In Hume’s day, the important balance was the balance of trade; and Hume’s price–specie–flow mechanism aimed to show how international trade was self-balancing through gold movements. In the nineteenth century, the purchase and sale of assets became important, but this did not change the basic story, since foreign capital investments were regarded only as deferred purchases of the capital importer’s goods. Capital would flow from countries where saving was abundant and labour scarce to countries where saving was scarce and labour abundant. Capital-importing countries would repay their loans out of the increased exports the investment of the loans had made possible, eliminating the temporary imbalances. In effect, lending and borrowing capital (savings) replaced gold flows in adjusting the trade balance in the long-run.

There was also a long tradition of bankers lending money to needy foreign sovereigns: the Rothschilds, as we have seen, were international bankers, lending and borrowing across frontiers without regard to trade balances. However, standard trade theory, with its denial that money had ‘motives of its own’, regarded such flows as merely lubricating the real trade in goods and capital.

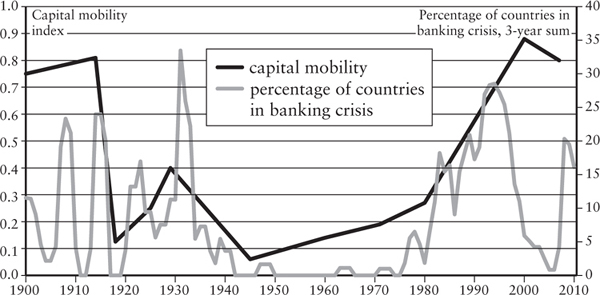

After the Second World War, trade was gradually liberalized, but capital flows were severely repressed. Most of these flows were political or ‘official’, such as Marshall Aid from the US to Europe and equivalently to Japan, and World Bank loans to developing countries. International financial flows within the banking system were minimal. Current accounts more or less balanced. The repression of capital movements brought to an end the succession of banking crises.

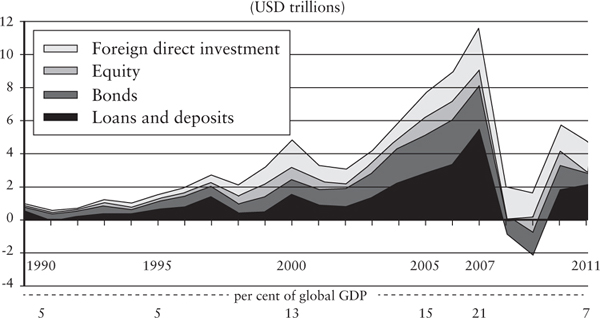

The unfreezing of the banking system started with the recycling of the OPEC surpluses in the 1970s. Freedom of capital movements, it was now argued, would make ‘capital allocation more efficient’. Financial flows multiplied relative to trade flows: in 2011, the total exports of merchandise and commercial services increased by $21.3 trillion, while the volume of foreign exchange transactions reached $4 trillion a day. Trading in liquid assets – bank loans and equities – dwarfed direct foreign investment. An uncontrolled banking system was left free to place its bets anywhere. As long as current account deficits were being financed, no one paid any attention to them. But as John Harvey wrote: ‘the driving factors of these massive financial flows [are] . . . fundamentally distinct from those determining trade flows – different people, different agendas, different goals and worldviews’.3 None of this worried the apostles of financial deregulation.

Figure 62. Capital mobility and banking crises2

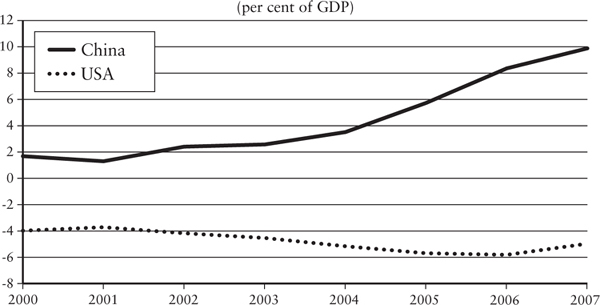

By 2007, the US was running a persistent and growing current account deficit; East Asia, especially China, but also Japan and Middle East countries (major oil exporters) were running persistent and growing current account surpluses. In Europe, Germany was running a persistent current account surplus; the peripheral Eurozone countries were running current account deficits, especially in the five years pre-crisis. Spain’s deficit, for example, grew from 4 per cent to 10 per cent of GDP in that period.

Current account imbalances might be problematic for three reasons:

1. Surplus countries might hoard their surpluses, imposing deflation and unemployment on their trading partners in a fixed exchange system (the Keynes problem).

2. Deficit countries might live ‘beyond their means’ if they could persuade creditors to finance their spending. But this was bound to lead to default sooner or later.

3. Deficit countries were especially vulnerable to ‘capital flight’ since they were more likely to default on their loans.

With capital becoming internationally mobile, the whole structure of global lending and borrowing came to depend on banks’ ability to judge risks correctly across the globe. All these structural factors came into play in the run-up to the crisis and its unfolding, rendering the world economy less stable, and recovery from the slump more difficult.

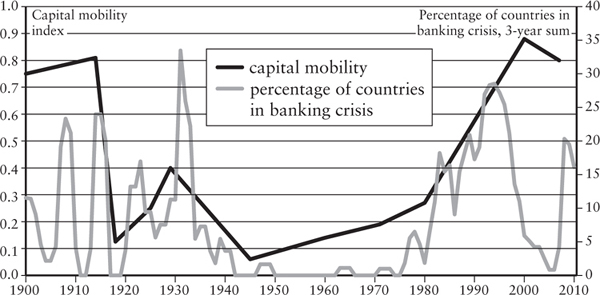

The two graphs below show how current account imbalances built up in the years before the crisis. Figure 63 shows the growing imbalance between the USA and China. In the Eurozone, north-western Europe, led by Germany, was the main surplus area, with the Mediterranean countries running persistent deficits. (see Figure 64)

This pattern of imbalances, while somewhat worrying, was regarded as temporary. Ben Bernanke wrote: ‘Fundamentally, I see no reason why the whole process [of rebalancing] should not proceed smoothly.’4

Martin Wolf, the respected Financial Times columnist, published a book in 2004 called Why Globalization Works. He saw globalization as a mighty engine for ending global poverty, and saw no problem arising from the macroeconomic imbalances that resulted from lopsided trade. As he wrote:

Figure 63. Current account balances, pre-crash: China and USA5

Figure 64. Current account balances, pre-crash: Eurozone core and periphery5

This pattern of surpluses and deficits will create difficulties only to the extent that the intermediation of the flows from the savings-surplus to the savings-deficit countries does not work smoothly. But no insuperable difficulty should arise. If some people (Asians) wish to spend less than they earn today, then others need to be encouraged to spend more.7

As late as mid-2007, he thought that the possibility that ‘huge calamities’ could be generated by world financial markets ‘looks remote’.8 Two months later, with the onset of the banking crisis, he was having second thoughts: ‘Today’s credit crisis . . . is . . . a symptom of an unbalanced world economy.’9

In the standard presentation of national accounts, a country’s current account position is equal to the difference between its domestic saving and investment.

The equation for national output is:

Y = C + I + (X – M)

where Y is output, C is private and public consumption, I is private and public investment, and (X – M) is exports minus imports, or the trade balance, which generally is the principal determinant of the current account balance (CAB). Therefore we can write:

CAB ≈ (Y – C) – I

(≈ is approximately equal).

If Y = C + I, and S (saving) = Y − C, then S = I. Thus

CAB ≈ S – I

CAB is in balance when S = I. An imbalance between a country’s exports and imports is thus definitionally equal to the difference between its domestic saving and investment. A country with a trade surplus needs to consume more or export saving (capital); a country with a trade deficit needs to consume less or import saving (capital). Indeed, if one believes that money flows like water these adjustments are automatic.

This is the standard view. But it has been challenged by economists who treat financial flows as independent of the current account. We will take up their argument later.

There were at least four reasons to worry about the sustainability of the current account imbalances in the pre-crash years. First, Figure 63 (p. 336) shows that in the case of China and the United States the money was flowing the wrong way – the phrase is ‘uphill’ – from a capital-poor to a capital-rich country, something Hume had denied was possible. China wasn’t importing development capital from the United States to plug the deficiency in its domestic ‘savings’. China was accumulating savings through its export surplus, which it was investing in US Treasury bonds. There was no net loss of money from the American economy. This allowed the Fed to keep money cheap.

Secondly, in the case of the Eurozone, finance was flowing the right way – from capital-rich north-west Europe to the capital-poor Mediterranean countries plus Ireland – but it was being used partly for unproductive purposes: to finance consumption and to speculate in real estate, rather than to develop the competitive position of the borrowers. Greece was like the businessman who gets a loan from the bank to expand his business and spends it instead in riotous living. Once the real estate market collapsed, the question of ability to repay became crucial.

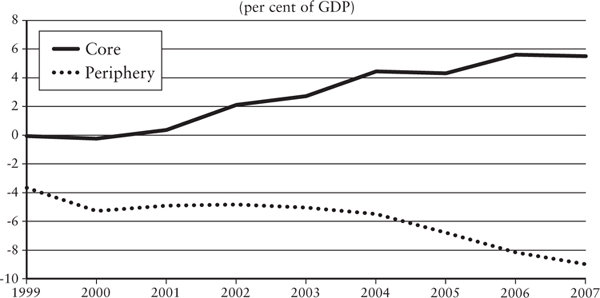

Figure 65. Total cross-border capital inflows10

Thirdly, in the past, most foreign investment took the form of direct foreign investment: buying physical assets like mines or plantations or railways which are immovable. In recent times, much of it has been ‘hot money’, short-term loans which could be withdrawn quickly; so much so that the booms and busts caused by hot money are not ‘a sideshow or a minor blemish in international capital flows; they are the main story’.11 So financial flight was a more likely consequence of a collapse in business confidence than in the nineteenth century, though this had already started to be a problem under the restored gold standard of the 1920s.

Finally, although gold hoarding was not unknown in the nineteenth century, reserve accumulation was a more prominent feature of the pre-2007 position. This was particularly true for a handful of countries in East Asia and the Middle East. Between 2003 and 2008, total international reserves (90 per cent of these being foreign exchange reserves) grew at an average rate of 17 per cent per year12 at a time when global GDP was growing at an annual average of 5 per cent.

Under the gold standard, this accumulation of reserves would have amounted to a big increase in deflationary pressure, because these reserves would have been held in gold – buried in the vaults of the central banks. However, the pre-crash position was dominated by the ‘exorbitant privilege’ of the US dollar as the principal reserve currency. The fact that the reserves were held mainly in dollars allowed the US to avoid deflation, and instead run an expansionary monetary policy.* The reserve position of the dollar formed the link connecting reserve accumulation by China and expansionary monetary policy in the US.

Now consider the proposition

CAA ≡ −CAB

This says that country A’s surplus is exactly the same as country B’s deficit. But which causes which?

Country A might run a current account surplus because country B pays for a part of country A’s goods with money rather than with goods. Country B’s deficits with country A are then said to be caused by country B’s spendthrift habits. Or country B might run a current account deficit because country A’s policies – for example, restricting consumption or maintaining an under-valued currency – prevent country B from exporting enough to it to cover its imports from country A. Country B’s deficits are then said to be caused by country A’s ‘saving glut’. Which is it? You can choose between China’s frugality and American extravagance.

The ‘saving glut’ thesis was the orthodox pre-crash view. Think of the world as a single economy, in which all the saving is done in China and all the investment is done in the United States. If the Chinese want to save ex ante more than the Americans want to invest, Keynesian theory tells us that saving S and investment I are equalized ex post not by an an appropriate interest rate adjustment, but by a fall in global income. In these terms, the collapse of 2008 was caused by the collapse of investment in the United States, with the world economy shrinking to equalize saving and investment ex post.

Keynesian theory tells us why this must be the case. It is not saving which finances investment, it is bank credit. If bank credit is demanded for speculation, not investment, it has no effect in either reducing saving or increasing investment. The imbalance between the two is reduced by a fall in income. A Keynesian would say that the only way to tackle this ‘structural’ imbalance is by reducing the propensity to save in China and increasing the inducement to invest in the United States.

On the eve of the recession in 2007, the Chinese saved half of their incomes, but invested only 40 per cent at home, much of it in lossmaking state industries. So 10 per cent was parked abroad, mostly in US Treasury bonds.

Why was China saving so much? Economist Michael Pettis offers an under-consumptionist explanation. China’s high savings ratio was structurally determined by the highly unequal distribution of income and absence of a social safety net. The poverty of domestic consumption led to a business model based on export-led growth through currency under-valuation. The purchase of US Treasury bonds was part of a deliberate policy of keeping the dollar over-valued in order to help Chinese exporters. (Alternatively, one might see China’s reserve accumulation as a form of precautionary saving following the East Asian financial crisis of 1997.)

On this interpretation, it was the excess of Chinese saving over its domestic investment which caused the US deficit. It was the willingness of China to finance the US deficit for its own purposes which enabled the American consumer to go on a spending spree. The Chinese purchase of US government securities created the conditions for a credit expansion in America, with the People’s Bank of China acting as an additional source of reserves for the American banking system.

The remedy for the current account imbalance with the United States is for the Chinese to boost their domestic consumption and productive domestic investment. This requires a social safety net and banking reforms.13

The ‘money glut’ or American spendthrift explanation starts at the other end. It was American over-spending on consumption and speculation in real estate that forced the Chinese to run a surplus. The structural problem lay with the US not the Chinese economy.

The economist Raghuram Rajan has described a situation in which

America’s growing inequality and thin social safety net create tremendous political pressure to encourage easy credit and keep job creation robust, no matter what the consequences to the economy’s long-term health; and where the U.S. financial sector, with its skewed incentives, is the critical but unstable link between an over-stimulated America and an underconsuming world.14

Alternatively, one might seek to explain the persisting American deficit in geopolitical terms: the simultaneous quest for guns and butter was part of the US commitment to policing the world without making any sacrifice in its domestic living standards to do so.15

The source then of America’s structural deficit can be traced to the stagnation of real earnings in the United States. Easy money in the US produced no upsurge in US domestic investment. Rather, the precrash years saw a ‘dramatic swing in corporations’ use of their internal cash flow . . . from fixed investment to buy back of company stock and cash [i.e. dividends] disbursed to shareholders’.16 As a result, cheap money hardly raised the US investment/GDP ratio. Why? American businesses could have borrowed for investment rather than speculate in property and mergers and acquisitions. Why didn’t they?

One explanation is that the prospective rate of return on large classes of fixed investment acceptable to American investors had fallen below the rate of interest, low though that was. For a time ultra-low interest rates supported the construction industry and speculation in real estate. When the Federal Reserve raised the federal funds rate between 2004 and 2006, this source of activity, too, was fatally damaged. Analysts are free to apportion the blame between a dearth of investment opportunities (‘secular stagnation), the quest for shortterm shareholder value, and favourable tax treatment of stock-options.17 Ironically, Chinese investors, who would have been willing to invest in the American economy long-term, were debarred from doing so on security grounds.

It should be obvious that Chinese ‘over-saving’ and American ‘under-investment’ are the same thing looked at from different theoretical perspectives; which ‘caused’ the other is impossible to determine empirically. Perhaps one should say that the world was kept in an unstable equilibrium by extreme saving (surplus) in China and extreme dissaving (deficit) in the US. The two extremes held the world economy together until the sub-prime crisis in the USA unwound the unstable forces.

The structural flaw in the EU’s Single Currency Area was obvious from the start; it was a monetary union without a political union. Much of the economic growth of poorer (largely Mediterranean) members depended on continual transfers of capital from the core to the periphery. In 2009 German banks accounted for 30 per cent of the debt owed by Greece, Portugal, Ireland, Spain and Italy. When European banks were contaminated by the US-generated securitization crisis, the inter-bank lending market collapsed and the flow of private capital was reversed. Capital flight forced peripheral-country governments to borrow from the bond markets to service the debts of their domestic banks to northern European banks. As government balance sheets exploded, risk premia on government debt rose in what Paul de Grauwe has named the ‘vicious circle’ between bank recapitalizations and the undermining of governments’ creditworthiness.18

In line with the saving glut thesis one can argue that German current account surpluses reflected deliberate German policy to restrain wage growth so as to improve cost competitiveness. This opened a wedge between German and peripheral Eurozone labour costs.

But lack of cost competitiveness doesn’t seem to have been the main problem for the heavily indebted European countries. Rather it was that capital imports were not being used to generate sufficient foreign earnings to service and repay the loans. Instead, a debt-financed construction and consumption boom caused current account deficits to widen in Ireland, Spain, Greece and Portugal before the crisis, which required more financing. Financial flows then reversed, not because current account deficits suddenly looked worrisome, but because the collapse of the construction boom had made many borrowers in those countries insolvent. Widening current account imbalances were symptoms of the problem, not its cause.

Surveying the whole scene, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that, in the advanced world at any rate, governments had surrendered to bankers the job of keeping their economies afloat. They allowed money to be pumped from one centre to another in a widening circle of financial betting, convincing themselves that if the money wheel could be kept spinning, nothing much could go wrong with the world economy.

From this point of view, the debate between the saving and money glut theses is something of a red herring. Yes, it is quite true that China and Germany should consume more and save less; and that the United States should consume less and save more. But there is no incentive to do anything about either set of imbalances, as long as economists and policymakers believe in leaving control of financial flows to the financiers.

In the nineteenth century it made sense to talk of British or French savings ‘flowing abroad’ to finance the capital development of their clients, because capital-rich countries like Britain and France alone had the financial markets able to mobilize money for foreign loans. It was not accidental that financial facilities were located in the country in which saving (in the sense of non-consumed income) was most plentiful. But even then there was no automatic connection between a current account surplus and foreign lending: the Rothschilds raised money from a variety of locations. The link is even weaker today, when we have a global banking system, largely detached from a specific country location, handling the money of a global elite of rich investors.

As Borio and Distayat of the Bank of International Settlements point out, a capital import is not necessarily some other country’s saving. It is a credit advanced by a financial institution in one country to an investor or government in another country. The two BIS authors thus reinforce an argument central to Keynes’s economics, namely, that saving is simply a decision not to consume; it is not a decision to invest. Investment is not financed by saving; it is financed by bank credit. It is financial facilities (deposits) provided by banks, not savings, which create purchasing power.19 Such deposits can be generated anywhere, even in deficit countries. (Indeed, this was the case of the UK, which had a current account deficit with many economies in the Eurozone periphery, but which was nonetheless a major geographical source of credit.) Thus, while current account balances almost perfectly match net financial flows due to accounting identities, there is no necessary connection between gross capital flows and current account balances.

What causes the level of investment to be what it is has nothing to do with what people want to save. It depends on the ability of businessmen to finance their investments, or on the creditworthiness of borrowing governments. Where the money comes from, in a system of free capital movements, depends on where the originating banks are located. This need not be where savings (in the accounting sense of non-consumption) are most plentiful. Thus there cannot be any direct connection between gross capital flows and current account imbalances; and therefore between current account imbalances and the financial meltdown of 2007–8.

It wasn’t the current account imbalances that were unsustainable in 2007–8; it was the balance sheets of the banks. The banks were like sovereigns allocating money, often for speculative motives, without any reference to current account positions. It was only when the banks got into trouble that the current account positions of the countries of destination came under critical scrutiny, with the debtor countries most exposed to capital flight.

As with any dispute between debtors and creditors, apportionment of blame is, ultimately, a value judgement, which cannot be settled by accumulating facts. In both the USA and the Eurozone, the proximate cause of the banking collapse lay with the banks; at a further remove, with governments in rich countries which relied on credit expansion as the alternative to public investment and redistributive taxation; and, at a still further remove, with the economics profession that lauded diseased banking practices on the ground that they facilitated the ‘efficient allocation of capital’.

The economic crisis has, in some cases at least, produced the market-led adjustment which eluded policymakers. The American trade deficit shrank from 5.8 per cent of GDP in 2006 to 2.4 per cent of GDP in 2016. China’s surplus with the rest of the world contracted from a peak of 9.9 per cent of GDP in 2007 to 1.8 per cent in 2016. Germany’s current account surplus with its fellow Eurozone members narrowed to just under 3 per cent of GDP in 2016 (although its overall surplus stood at a massive 8.3 per cent). In each case, the trade ‘correction’ has come about more through the shrinkage of consumption in the debtor countries than through an expansion of consumption in the creditor ones. Thus the ‘rebalancing’ that Bernanke and Wolf foresaw is taking place because of a fall in national income in the debtor countries. But, since the structural causes of the imbalances remain largely in place, any strong recovery of Western economies is bound to re-create them.

* Because it did not have a fixed supply of gold, the US was able to issue as many Treasury bills as it wanted.