The collapse of 2008–9 should have shifted the attention of macroeconomics from the problem of inflation in otherwise stable economies to the problem of economic, and especially financial, instability. That it has barely done so is my main excuse for writing this book.

The most important economic problems we face today stem from the wrong views about money and government. If one starts from the position that, in the absence of money, a market economy is optimally self-adjusting, then the principal, in fact only, task of macroeconomic policy is to ensure that money does not upset the equilibrium established in the (barter) economy. The belief that the market economy is optimally self-adjusting is usually, but not logically, connected with another: that the main source of economic disequilibrium arises from governments printing too much money. From this it follows that the task of keeping money ‘in order’ or, equivalently, the price level predictable, needs to be ‘outsourced’ to central banks equipped with inflation targets. As a corollary, governments should be bound by fiscal rules that prevent them from issuing money at will to pay for their spending. If one has the right monetary regime, supported by the right fiscal rules, the market economy will normally be stable.

The above was the dominant implicit model of political economy from the dawn of scientific economics in the eighteenth century until the collapse of the 1930s. Though actual events failed to confirm it, they were not sufficiently inconsistent with it to force a rethink of the foundations of the discipline or the principles of policy. Specifically, although crises were frequent they could be interpreted as temporary interruptions to a strongly upward momentum of economic growth. This strongly expansionist phase of capitalism ended in the 1920s, and the subsequent collapse and stagnation gave birth to the Keynesian revolution.

The Keynesian message was straightforward: if growth was to continue it was not enough to control money and keep government out of the way. The government had to be inserted into economic life as an active engineer of growth: the control of money required that it control the level of demand in the economy. After thirty years, the Keynesian system fell victim to its own success, the managed capitalism it introduced proving unable to control inflation at full employment. This reopened the road back to pre-Keynesian orthodoxy. Provided only money was kept in order by independent central banks, a lightly regulated market system could be relied on to keep economies growing steadily and stably.

The pre-crash period of the Great Moderation, running from the early 1990s, did not exactly conform to this benign prospectus: there were several financial collapses, unemployment was higher, and growth lower, than in the Keynesian age. But it did not disconfirm it sufficiently to challenge the ruling paradigm. Inflation was low and growth was reasonably stable. It was possible to believe that the era of boom and bust had come to an end.

It is impossible to regard the collapse of 2008–9 and subsequent events as merely a temporary halt on the continuing upward ascent. There is a whiff of ‘secular stagnation’ in the air, with a strong sense that bouts of temporary excitement will be followed by collapses. Make hay while the sun shines is what the market analysts advise us.

Despite the brittleness of the contemporary market economy, the Keynesian theory of macro-policy, which made the state responsible for managing the level and influencing the direction of total spending, has not been rehabilitated. Money and governments continue to be perceived as sources of shocks to an otherwise smoothly adjusting market system. Attacks on public deficits and debts continue to overwhelm concerns for employment, economic growth and equity.

In the last quarter of a century we have come close to creating a single world economy. Questions about the role of money and of government increasingly have to be asked and answered in a global context.

The matters at issue can be made more precise by considering what framework of policy and institutions is needed to make market economies work acceptably well.

Terence Hutchison has helpfully classified opinions on this question as continua along three different curves: doctrinal, institutional and historical. Along the first curve is a range of doctrines stretching from those who assert a very smooth and rapid self-adjustment of markets up to optimal levels, to those who assert that this self-adjusting tendency is weak or non-existent.

Along the second curve views stretch from whether the framework of institutions, rules and policies needed to maintain self-adjustment is simple, natural and easy to bring about, or very complex and nearly impossible to set up. And finally, there is the historical evidence: does history show that optimal self-adjusting processes are normal or exceptional?1

Simplifying, if we consider just neo-classical and Keynesian economics, we find near one end of all three curves the Chicago School, and near the other end the Keynesian School.

Chicago School proponents believe that smooth and rapid self-adjustment to full employment is normal within a framework of rulebased monetary policy and ‘light touch’ regulation. Keynesians deny that a market system has an automatic tendency to full employment. It achieves this happy state only in ‘moments of excitement’. In the Keynesian perspective, the dynamics of adjustment to ‘shocks’ point the economy away from, not back towards, an optimum equilibrium. Therefore, governments should actively pursue full employment policies, with such regulation of private sector activity as is necessary to bring this about.

The Austrian, Marxist and Schumpeterian schools lie at tangents to this central debate.

The Austrians believe that the information required for market selfadjustment exists only in the minds of actual market participants. This being so there is no scope even for minimal macroeconomic policy, since the central authority can never ‘know better than the market’. The only alternative to market self-regulation is central planning; but this will deliver grossly inferior outcomes. No monetary policy is required if banks are subject to a 100 per cent reserve requirement. On the other hand, a well-functioning market system requires what Hayek called a ‘constitution of liberty’, which secures the maximum possible decentralization of market and state power, within a firm framework of law, consistently enforced. Such an equilibrium may not be ‘optimal’ in the neo-classical sense, but it is the best that can be done in a free society.

Both the Marxist and Schumpeterian theories are best thought of as disequilibrium theories. The key thought is from Marx’s Communist Manifesto: under the restless dynamism of competitive capitalism, ‘All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned . . .’2 According to Marx, no policies or institutions can be set up within the capitalist system to avoid recurrent and increasingly savage crises. This is because the profitability of capitalism depends on a growing reserve army of the unemployed. Equilibrium can be achieved only with the abolition of capitalism.

Schumpeterian economics likewise denies that there is either a unique full employment equilibrium or the variety of equilibria posited by Keynes. Capitalism is a dynamic disequilibrium system. There are phases and epochs, waves long and short. Keynes may have bequeathed a twentyfive-year boom, but this was just a phase of a long cycle – perhaps a Kondratiev mass production cycle. Nevertheless, there is a potential meeting between Keynes and Schumpeter, since Schumpeter, like all the earlier generation of Real Business Cycle theorists, would not have denied that stabilization policy could make the rocking less violent.

The Hutchison scheme needs one crucial modification. All the economic doctrines above presuppose the existence of some kind of state, even a minimal state. We will see that the main flaw in globalization is the attempt to integrate markets on a global scale without a state. This has rendered life in the market more insecure, more criminal and less legitimate. Markets without states are mafias.

Chicago School economics has recently been the economics ‘in power’. The collapse of 2008–9 and its aftermath has been a kind of experimental test of its main theses. Do we still think of the market system as naturally stable, provided only that money is kept ‘in order’? Surely not. Money was kept in order by the principal criterion of the time, price stability, but the economy collapsed nevertheless. Was it the vexatious interference of governments which upset the even tenor of production, trade and finance? Again, surely not. Since the 1980s there has been a big withdrawal by governments from active management and regulation. It was the deregulated global market that collapsed in 2008–9.

To be sure, one disaster should not be the test of a system’s performance, any more than one aeroplane crash should discredit the theory of aerodynamics. However, the ‘shock’ of 2008–9 was, as we can now see, building up under the surface of a brittle prosperity, and it has left great damage in its wake from which it will take many years to recover. In other words, the question of which state of affairs is to be viewed as ‘normal’ – the so-called Great Moderation of the early 2000s or the ten post-cash years which followed – is still open.

These rather dry academic questions, translated into popular discourse, have become the urgent matter of contemporary politics. Since the global meltdown of 2008–9, hostility to neo-liberal statecraft has focused on globalization. Globalization has long been the picture-postcard of neoclassical economics and neo-liberal politics. In polite circles, it is still considered impious to question it. But the strains of globalization have led to an upsurge of sometimes ugly popular protest, which threatens the political legitimacy of liberal democracy.

The conclusion arising from my account seems to me inescapable. The working of the economic machine needs to be drastically improved and the rate of disruptive change slowed down to societies’ (considerable) capacity for adaptation if a decent political system is to be maintained. If not, a regression to nationalism or even fascism is likely. The urgent need is to detach the championship of liberal politics from the defence of neo-liberal economics. Keynes understood that supremely well, and it is in his spirit that the following suggestions are offered.

The essential requirement of a new macroeconomic constitution is to reverse the current balance of fiscal and monetary policy. The focus should shift from fighting inflation to fighting stagnation. This means using the budget to revive growth, and monetary policy to support fiscal policy.

Restoring Treasury control over macro-policy does not mean reverting to ‘full employment’ of 1950s vintage. By full employment I mean a ‘socially’, that is, politically and morally, acceptable level of activity. I would apply the same criterion of political and moral acceptability to inequality of wealth, earnings and incomes. Vague though these criteria are, economic policy must have some reference to what the public considers reasonable and fair if it is to escape from statistical culs-de-sac.

The narrative of ‘the deficit’ still dominates popular discussion. Deficits are what you always get, the orthodox story goes, when you allow politicians to ‘monkey around’ with money. President Donald Trump’s tax cuts have been attacked by academic macroeconomists, not just for worsening inequality – a reasonable reaction – but also for increasing the deficit. Philip Hammond, Britain’s Chancellor of the Exchequer, cannot invest in the social housing Britain desperately needs because it will risk his self-imposed borrowing limits.

This discussion is fundamentally unhinged. Whether the budget is balanced or unbalanced is a secondary matter. What matters is whether the economy is balanced or unbalanced at full employment, and what contribution the state budget can make to this. To offset a decline in private spending, the budget deficit has to be increased, not reduced. Instead, governments in 2009–10 set about reducing their deficits by raising taxes and cutting spending before private spending had recovered. The result has been several years of under-employment.

In the Ricardian world view, government spending is simply waste. It subtracts from productive investment, and should be limited to the few essential functions of the state. Its claim is that the private sector will provide the community with all the capital equipment it wants or needs. This is doubly false. From time to time capital may ‘go to sleep’, as even J. B. Say recognized. And Adam Smith himself acknowledged the need for state investment to provide public goods.

Keynesian economics built on Say’s insight. Because of uncertainty, the volume of private investment will normally be less than what the public would save at full employment. Because of liquidity preference, nominal interest rates will be sticky downwards, whatever Bank Rate set by the central bank. Thus there is a permanent role for public investment to keep a growing economy at full employment. It may also be the case that public investment will need to expand to fill the growing gap between private saving and investment as economies become richer – at least to the point at which there is no further benefit to be had from adding to the community’s capital equipment.

The second argument for public investment is that, owing to various ‘failures’, private capital markets cannot provide the community with all the capital goods it needs. This is what Adam Smith meant when he talked of investments greatly advantageous to the ‘great society’ which private investors lack the incentive or means to supply (see p. 82).

The public goods argument for a state investment function is that certain goods have public benefits additional to their private benefits. These external benefits cannot readily be ‘internalized’ by private firms because they are in essence ‘free’ goods, so there is no money to be made from supplying them. Public investment is justified in goods and services whose benefits to the ‘great society’ exceed their market value. One may think of such goods as constituting the political, legal, physical and moral infrastructure of a market economy. The state itself is the main public good. The community ‘invests’ in the state by paying taxes. How much tax people are willing to pay is a reasonably reliable indicator of how much they think the state is worth. Only an extreme free marketeer would claim that sufficient law and order would be provided by private protection agencies. Through its ability to tax, the state provides or supports a derivative set of public goods such as transport systems, public utilities, hospitals, schools, housing and elements of the moral, legal and religious order. Private markets would not provide enough of such goods, or in the right places, to serve the needs of the ‘great society’. If capital investment were left entirely to the market it would come to an end long before its potential to raise material and spiritual well-being was exhausted.

Mariana Mazzucato (and others) have shown, correctly, that the state has played a crucial historical role in encouraging innovation.3 To cite a particularly striking example: ‘all the technologies that make the iPhone a smart phone were funded by the state, including the internet, GPS, touchscreen display and the voice-activated Siri personal assistant’.4 State subsidy of innovation is justified because the state will be a more ‘patient’ investor than the private sector, more willing to gamble on an uncertain future. It is therefore a critical part of the process of capital accumulation which drives growth – a point recognized by the mercantilists, but foreign to ‘scientific’ economics. In analysing public investment banks, Mazzucato has suggested that they have played four different roles: as missionaries; as venture capitalists; as investors in infrastructure; and as countercyclical lenders. The latter was very clear during 2009–10 when institutions such as the Brazilian BNDES and the German KfW substituted for dried-up private bank lending.5 The European Investment Bank has started to do the same in the European Union.

Thus, for both uncertainty and public goods reasons, Keynes in 1936 expected to see ‘the State, which is in a position to calculate the marginal efficiency of capital-goods on long views and on the basis of the general social advantage, taking an ever greater responsibility for directly organising investment’.6 However, things have gone in the opposite direction.

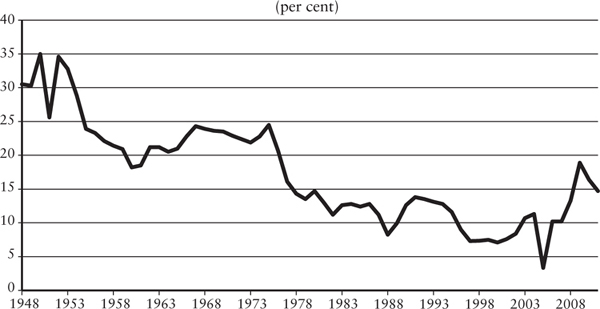

In the UK, public investment as a share of total investment fell from over 20 per cent in the 1950s and 1960s to about 10 per cent from the 1980s onwards, with a brief spike under Gordon Brown. Ideology has minimized the importance of market failure and magnified the importance of government failure. Even so-called serious commentators believe the state is bound to ‘pick losers’. The question, of course, is not whether government always succeeds, but whether government failure is likely to be greater or lesser than the market failures it seeks to correct.

Figure 66. UK public investment as a share of total investment7

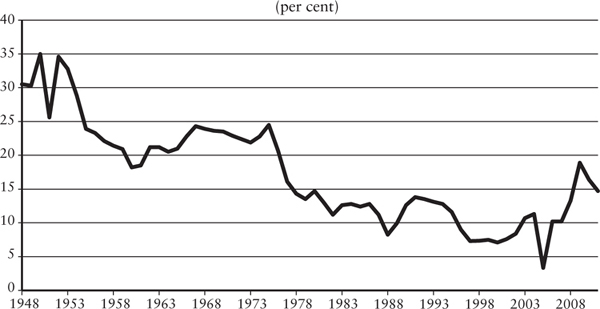

The principles of a sensible fiscal constitution might be as follows:

Current spending should always be covered by taxation. There is much to be said for the old British Treasury rule that the budget for current spending should be set to balance annually, budget balance providing a surplus (sinking fund) to pay down debt. The current spending budget should include all transfer payments, i.e. social security benefits, pensions, etc.; the more desirable these are regarded as, the higher taxation will need to be. In a recession, sinking fund payments would be reduced or suspended, the resulting deficit being used to finance public works instead. There should be a buffer stock of such works, which would be expanded in a downturn and contracted in an upturn. Providing people with work, even temporarily, is better than paying them to do nothing. Public works schemes should be located in areas of high unemployment and should offer employment at the minimum wage. Whether such schemes add to the nation’s stock of assets is immaterial. Much more important is the role they can play in keeping the link to work.

The important fiscal rule for the capital budget is that the state should be prepared to borrow for any beneficial capital spending additional to the normal capital outlay of the private sector. The role of the central bank is to enable it to borrow for such purposes as cheaply as possible. The aim should be to restore public investment to about 20 per cent of total investment. The purpose of this is not so much to use public investment as a counter-cyclical tool (though housing construction could fairly easily be expanded and contracted with the cycle), but to provide a sufficiently large and steady stream of demand to smooth out fluctuations in private investment.

In theory, all public investment could be a charge on the state’s capital budget. However, where projects are potentially profitable but, for short-termist or other reasons, unattractive to private investors, there is a good case for outsourcing them to independent or quasi-independent institutions, such as a State Investment Bank, run on commercial lines. The reasons for doing so are partly psychological. Their borrowing would be ‘off budget’ and so avoid the hostility which attaches to any increase in the government deficit.8 Public confidence in the value of their investments will be increased if they are seen to be independent of politics. But there are also solid economic reasons. The managers and employees of such an institution would be able to provide technical services and skills which a government bureaucracy lacks. The commercial aim of the Bank would be to earn a rate of return on the average of its investments equal to their cost.

How would it work? The Investment Bank would be capitalized by the state, and empowered to borrow an agreed multiple of its capital for approved purposes; that is, the state would determine the Bank’s strategic direction, and the managers would have full operational independence. Depending on the Bank’s mandate, such purposes might include investments in energy efficiency, long-term loans to small enterprises and start-up companies through a network of local banks, and support for private venture capital initiatives like FinTech. Being state-owned, the Bank’s implicit taxpayer guarantee would enable it to finance projects that would be unviable at the usual risky lending rate. Considered an almost revolutionary innovation in Britain and the United States, public investment banks are up and running in a number of European countries, with good results.9

France, Italy and other countries also have state holding companies, operating transport and public utilities. Italy has successful state holding companies (IRI and ENI) involved in a wide range of enterprises, not just natural monopolies. If the railways, water companies and parts of the energy sector are renationalized in the UK, as the Labour Party has proposed, a state holding company, at arm’s length from the politicians, would be the right vehicle for public investment in them. The case, though, still needs to be made that public ownership of such companies is superior to regulation.

Where investment projects require a long-term taxpayer commitment, as would be true of new hospitals, schools, colleges and universities, and fundamental scientific research, the state should raise the capital itself, with money for recruiting extra staff being a charge on the capital budget for the period of the loan. Although they lack a calculable social rate of return, such investments may still be, as Adam Smith said, ‘in the highest degree advantageous to a great society’. Taxpayer commitment need not imply a growing taxpayer liability. Although they do not directly ‘pay for themselves’, they do so indirectly by raising productivity. That the state is, uniquely through its power to tax, in a position to reap such unpriced benefits is probably the strongest argument for increasing the state’s share of investment from its present low level.10 But just because state investment lacks what Janos Kornai called a ‘hard budget constraint’, it is best to have a rule specifying its limits. The Gordon Brown rule to maintain a constant debt/GDP ratio is still the best on offer, though there is nothing sacrosanct about any particular ratio. Short-term fluctuations round the given ratio are to be expected, but a secular tendency for the ratio to rise would indicate that the social rate of return from public investment was reaching its limits.

The new fiscal constitution might look something like this:*

In 1984, the then British Chancellor, Nigel Lawson, announced that the object of macroeconomic policy was the ‘conquest of inflation’. This object came to be embodied in mandates given to nearly all central banks over the following years: to hit pre-set ‘inflation targets’ – usually in the region of 2 per cent annual inflation. To achieve these targets, central banks were given ‘operational independence’ over interest rates. Today, the urgent need is to ‘conquer under-employment’. In this situation, to be left with the ‘conquest of inflation’ as the only extant macro-policy aim is archaic, indeed nonsensical, when, for the last ten years, the problem has been deflation, not inflation.

Sensible economists, not all of them Keynesians, have recognized the absurdity of macro-policy being uniquely concerned with the price level, and have suggested altering central banks’ mandates. Central banks, they say, should be explicitly given a ‘dual mandate’ to include output as well as inflation. Simon Wren-Lewis, a leading British New Keynesian, has gone further: he suggests that when the central bank’s policy rate hits the ‘lower bound’ – putting orthodox monetary policy out of action – the central bank should be authorized to tell the government that fiscal policy is needed.11

It has been objected that broadening the mandates of central banks would destroy their hard-won anti-inflationary credentials by creating uncertainty about the future course of monetary policy. This objection has merit. But neither the proposal to widen central bank mandates nor the argument against it go to the heart of the problem – which is that monetary policy on its own is too weak to ensure the stability of the macroeconomy.

The mainstream analysis was that, provided only that the price of credit was controlled by the central bank, market economies would be cyclically stable at full employment. This was the Wicksellian promise, somewhere between monetarism and Keynesianism, and therefore embraced by New Keynesians as a compromise between the two. The allure of macroeconomic policy a la Wicksell was that it promised to achieve both price stability and full employment by means of a single instrument, Bank Rate, which would impact simultaneously (or after a short lag) on both prices and output.

In the period of the Great Moderation, from 1995 to 2007, this slimmed down machinery of macro-control seemed to run like clockwork. Inflation was stable and low, as was unemployment. Few economists can resist a correlation which seems to confirm their theories. The fact that there was, for a few years, a statistical link between interest rates and prices tells us no more about what caused it than do previous attempts to ‘prove’ the quantity theory of money. A better explanation of the correlation is the massive entry of cheap Chinese goods into the world market, which subdued inflation and enabled central banks to keep the cost of credit very low. Benefiting from a happy conjunction of events, central bankers attributed the Great Moderation to their own perspicacity.

Then came 2008. Far from being securely in the ‘long run’ of optimum performance, economies suddenly found themselves in the Keynesian ‘short run’ of falling output, with only interest rate policy available to fight it. When the policy rate hit the ‘lower bound’, central banks embarked on quantitative easing. Conventional monetary policy before the crash failed to avert a collapse; unconventional monetary policy after the crash failed to bring about a recovery. What experience since the 1980s suggests is that while dear money can cause a depression, cheap money cannot prevent one.

So what should be the role of central banks and monetary policy in the macroeconomic constitution of the future? If one believes that the collapse of 2008–9 was a one-off event, highly unlikely to be repeated in our lifetimes, then there may be no great case for changing the current central bank mandate. On this view, the permanent danger against which policy needs to guard is the inflation produced by voteseeking politicians. This remains the mainstream view.

On the other hand, if collapses on the scale of 2008–9 are an everpresent possibility in market economies, as both Marx and Keynes, for different reasons, believed, stabilizing the economy at a high level of activity will require more instruments than just interest rate policy. A central bank can only influence demand indirectly through setting a price for borrowing money; the government can influence it directly through its tax and spend policies. In short, if the economic drama is more Keynesian than Friedmanite or Wicksellian, central bankers should not have the starring role.

The following conclusions suggest themselves:

1. The ‘conquest of inflation’ is not today’s most pressing priority and hardly likely to be so for many years to come. Policy rates are still stuck at very near zero. They cannot quickly be restored as regulators of activity, and most serious people understand that it is lunatic to go on flooding the economy with money which is not spent on currently produced output. In short, monetary policy is as disabled now as fiscal policy was in 2010.

2. The view that central bank interest rate policy can, unaided, prevent inflation or deflation, is a myth. The low inflation of the Great Moderation was due not to the wisdom of central bankers, but to a favourable environment, which importantly included the ‘China price’. Strong deflationary forces made it impossible for monetary policy on its own to ‘lift’ the rate of inflation after the 2008 crisis struck, despite massive injections of central bank cash into the economy. The reason for the relative weakness of monetary policy is that its influence on aggregate demand is indirect.

3. Fiscal and monetary policy should be coordinated, not separated. The idea that ‘sound money’ is needed to guard against ‘fiscal excess’ comes from the set of ideas that regards government as the problem, never the solution. But if the problem is the natural volatility of the market system, government is a crucial part of the solution.

4. Because fiscal policy is the more powerful weapon (and because governments, unlike central bankers, are accountable to voters), the government should be the senior partner in macro-policy. Specifically, the trade-off between inflation and unemployment at any one time, or over several years, should be a matter of political judgment. It cannot be outsourced to technicians, whose job should be to advise on the consequence of political choices, not to make them.

5. Central banks would lose their independent control of interest rates. Their mandates should be to support the economic policy of the government. They would advise governments on Bank Rate, not decide it, and they would, uniquely for a state agency, have the right to publish their dissent. For countries with their own governments and their own currencies, a change in mandate simply requires a change in domestic law. This would, in effect, restore the position to what it generally was before the late 1990s. Such a change in the mandate of the European Central Bank is presently impossible, because there is no central government to tell the European Central Bank what to do.

6. Such a reform would deprive central banks of their policy role, but leave them with the vital task of ensuring the stability of the banking system. Regulatory tools, long in disuse, will need to be revived. Given the culpability of the financial system for the collapse of 2008–9, it is the central bank’s regulatory, not its policy, role that needs prioritizing.

The financial system caused the Great Recession, but it was allowed to. Its faults were licensed. Reform of banking that does not include regulating what banks are allowed to do will miss the point. As Professor James Galbraith tells it:

These are institutions with high fixed costs, with technologies and transnational legal structures that are designed to facilitate tax evasion and regulatory arbitrage, and which face very limited prospects for sustained profitability in activities that correspond to social need. Their entire structure isn’t viable in a world of slow growth, except by fostering short-lived booms followed by busts and bailouts. In short, the financial sector as a whole is a luxury we cannot afford.12

One could add that a corrupted capitalism is also a political luxury too far, because it is certain to provoke a popular backlash.

Because of the damage they inflict on the economy, banking collapses generally lead to the demand for banking reform. Following the Great Depression of the 1930s, the US Congress passed the Banking Act of 1933, popularly known as the Glass–Steagall Act, which separated deposit-taking from investment banking, and introduced deposit insurance for the former. The 2008–9 banking crisis also led to a reform agenda, aimed at limiting bank failures and hence recourse to the taxpayer for bank bail-outs. The difference between the two reform agendas is that the earlier one was embedded in a much more extensive programme of economic reform, whereas today the consensus view is that, provided only that the banking system can be made more ‘resilient to shocks’, everything else can continue exactly the same as before. (I abstract from the new world of crypto (encrypted) currencies started outside the banking system. Using digital technology to hide the transactions of their users from regulatory scrutiny, they have so far mainly been useful for speculation and money laundering.)

The earliest idea for reform was to break up big banks into smaller units – local, neighbourhood, regional. This would eliminate the ‘too big to fail’ problem, and reconnect banks with their depositors. In fact, the financial crisis has increased the concentration of the banking system, as such crises always do. The ten biggest banks in the US now control 75 per cent of American assets, as opposed to 10 per cent in 1990. So reformist ideas shifted to separating banks by function. This harks back to Glass–Steagall.

The principle of separating retail from speculative banking underlines the Paul Volcker-inspired Dodd–Frank Act in the USA, the Vickers-inspired Financial Services Act in the UK, and the Liikanen Report sponsored by the European Commission.13 The main idea behind all three is that deposit-taking banks should not also be investment houses. Such separation would reduce ‘moral hazard’: risky lending would not be publicly insured against loss.

The problem is that the core activity of retail banks has become the mortgage business. It was the retail not the ‘shadow banking’ sector which initiated the banking crisis of 2007: the British bank Northern Rock, which had to be rescued by the government and nationalized early in 2008, provided mortgages for a quarter of the population. Securitization made this supposedly safe business unexpectedly risky. Functional separation on its own will do little to check the credit cycle generated by mortgage-lending or limit taxpayer liability for its excesses. Compelling banks to hold mortgages for a period of years, plus a big boost to social house-building, would cool this particular inflammation.

More recently, the main aim of reform has been to make banks more ‘resilient’ to shocks.

Following the crash of 2008, the G20 set up a Financial Stability Board to improve global financial stability. In the UK, a Prudential Regulatory Authority was established in the Bank of England, charged with a ‘primary objective of identifying, monitoring and taking action to remove or reduce systemic risks with a view to protecting and enhancing the resilience of the UK financial system’. The EU’s Financial Stability Board (FSB) is tasked with implementing a Capital Requirements Directive (CRD), a Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD) and a Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM). The main object of these initiatives is to strengthen banks’ ability to survive shocks by strengthening their balance sheets ex ante. They include beefing up banks’ capital and liquidity requirements, regulating the derivatives’ market and strengthening creditor liability for bank failure.

The record of augmenting banks’ capital stocks, which started with Basel I in 1988 and continued with Basel II in 1994, hardly inspires confidence. Basel I and II required banks to hold ‘riskweighted’14 capital equal to 8 per cent of their assets. (See Ch. 11, pp. 317–18.) When the crash came, the actual equity of some of the major banks was only 2–3 per cent of their assets. The new minimum capital ratios stipulated by Basel III – up to 30 per cent for systemically important banks – similarly assume that risks are measurable either by the regulator or by the banks themselves. If they are unknown and unknowable, there will always be either too much or too little capital in store for the next turn in the tide of activity. To get round this problem, some central banks now have the authority to vary capital adequacy requirements countercyclically. But this assumes that the regulator can know accurately at what point in the cycle the economy, or any particular sector of it, has reached.

The capital adequacy approach to bank regulation has been predictably condemned by banking spokesmen. A typical complaint is that ‘higher bank capital requirements intensified the Great Recession, and renewed calls for tighter requirements threaten to cut the slowly recovering economy off at the knees once more’.15 A more credible complaint is that, if tougher capital requirements curtail the risky lending of systemically important investment banks, it will migrate to banks not subject to them. The vulnerability of the system as a whole will remain.

Banking ‘resilience’ is also to be improved by ‘stress testing’. Central bank regulators test how banks would fare in the event of another crisis. If they fail to meet their capital requirements relative to their risk-weighted assets, they will have to raise more capital. Mario Draghi, Governor of the ECB, said, ‘the ultimate purpose of [stress testing] is to restore or strengthen private sector confidence in the soundness of the banks, in the quality of their balance sheets’.16 Having spectacularly failed its latest ‘stress test’, the bailed-out Royal Bank of Scotland announced ‘important steps to enhance our capital strength’.17 Europe’s oldest bank, Monte dei Paschi di Siena, was trying to raise €5 billion, after failing its summer 2016 stress test. The problem with stress tests is not so much that banks will find ways to evade them, but that they rely on the same risk-assessment techniques that failed to spot the risks banks were running before 2007.

A more radical-sounding route to ‘resilience’ is to raise banks’ reserve or liquidity requirements. Cash reserves against deposits were run down to almost nothing pre-crash. This caused a credit-crunch when banks stopped lending to each other. Basel III seeks to ensure that at all times banks have enough sufficiently liquid assets to meet all payments due in thirty days. Since 2009, UK-based banks have been required to hold a buffer of central bank reserves or gilts, the amounts to be determined by ‘stress tests’. In the USA and China, 10 per cent and 20 per cent liquidity ratios are in force, respectively. The problem with this approach is that it assumes that reserves determine the amount of lending, whereas it is truer to say that lending determines the amount of reserves; that is, the central bank will always supply sufficient reserves to the banking system to prevent liquidity crises and volatile interest rates.

To deal with the threat of insolvency, central banks have set up ‘resolution regimes’. Their object is to allow the regulators to intervene early enough in the rake’s progress to ensure that the bank can carry on its business, while avoiding the taxpayer having to pick up the bill. This requires that the authorities have the power to restructure a bank before insolvency hits and possess a ‘bail-in tool’ to ensure that, in any restructuring, the bank’s losses are borne by its shareholders and creditors rather than by the taxpayer.18 The ambitious double aim is to forestall liquidations like Lehman Brothers and sovereign debt crises such as afflicted governments in Portugal, Ireland and Greece, when they bailed out their banks.

Such regimes have been enacted in the USA, the UK and the European Union. The EU, largely at Germany’s insistence, has gone furthest. Its Single Resolution Board, started on 1 January 2016, decides how much of any bank’s losses should be borne by its shareholders and bondholders. At the same time, the Commission agreed to restructure deposit insurance, by setting up a fund that will build up over eight years from ex ante contributions from the banking sector, with contributions proportionate to risks.

Since ‘resolving’ the affairs of a big ‘stressed’ international bank with hundreds of branches and subsidiaries, many different classes of shareholder, creditor and debtor, and located in dozens of separate jurisdictions, is likely to defy the best efforts of a Single Resolution Board, systemically important banks are being asked to submit ‘living wills’ to ensure that their mortality will not be at the public’s expense. Under the US Dodd–Frank Act, any bank with a capitalization over $50 billion must describe the company’s strategy for rapid and orderly resolution (i.e. liquidation) in the event of its failure.

The first eleven such ‘wills’ submitted by big US banks were deemed inadequate by the regulators. Unsurprisingly, Thomas Hoenig, Vice-Chairman of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, commented: ‘The plans provide no credible or clear path through bankruptcy that doesn’t require . . . direct or indirect public support.’19

In July 2014, the think-tank ResPublica published a report called ‘Virtuous Banking: Placing ethos and purpose at the heart of finance’. It argued that the ‘inherent lack of virtue amongst our banking institutions’ was the ‘root cause of the financial crisis’. It pointed out that fraud continued unabated. The ‘self-serving’ culture of banks needed to be challenged, as without this, banks would circumvent the regulations.20 ResPublica proposed a banker’s oath, modelled on the Hippocratic oath sworn by doctors, which would enjoin a duty of care on bankers towards their customers.

There are proposals to detach financial compensation from shortterm stock-price performance, to fine bankers for unethical practices, and to cap or claw back bonuses. Nick Leeson, the original ‘rogue trader’ whose exploits brought down Barings Bank in 1995, has cut through the thinness of these precautions: ‘If we are going to try and change a banker’s bonus structure, I think within 15 minutes they will have a new structure that works in the same way. They have the best accountants and lawyers.’21 The root of the problem is the greed for money. As long as bankers continue to believe that they can get away with flexible ethical standards, they will do so. Bankers have got off lightly. Banks have been fined enormous sums for frauds that in other professions would result in custodial sentences, but very few bankers are in jail.

The global financial system has grown faster than trade; and trade has grown faster than production. This is what Adair Turner means when he talks of the increase of ‘financial intensity’ – the ratio of financial transactions to total economic transactions. In advanced economies, bank balances as a ratio of GDP – a measure of financial transactions – had risen from 70 per cent in 1980 to over 450 per cent in 2011. Financial intensity is thus a measure of credit creation in excess of the needs of non-financial business. Its growth is what is meant by the ‘financialization’ of economic life.

Turner writes that ‘there is no evidence that advanced economies have become overall more efficient as a result of the post-1970 increase in financial intensity . . . and the development of a bigger and more innovative financial system led to the crisis of 2007–2008 and to a severe recession’.22 The reason for this is that most credit created by banks is not issued to finance new investment – the creation of new productive assets – but to expand consumption and speculate in real estate, currencies and stock markets. This leads to a volatile, destructive credit cycle.23

Proposals to reduce financialization include forcing banks to hold 100 per cent reserves against their loans, and abolishing deposit insurance. Such Hayekian measures to restrict credit creation would simultaneously attack the build-up of over-optimism and moral hazard. However, neither reform gets to the root of the ‘excess credit’ problem, which, we have suggested, is the stagnation of real earnings. This results in the substitution of speculative for productive investment and easy consumer credit for vanishing welfare entitlements. The globalization of finance amplifies both tendencies, since it gives banks almost unlimited opportunities for regulatory arbitrage.

An aspect of financialization little discussed in polite circles is the extent of its criminality. A sizeable fraction of the money sloshing around the world originates in criminal activity – often Russian and Middle Eastern – which is then ‘laundered’ through Special Purpose Vehicles set up in offshore tax havens under fake owners. Much of the laundering is done through London, which boasts the most sophisticated financial service industry in the world. Regulators run checks on the origins of deposits, but the volume of transactions defeats them. Closing down offshore deposits, or requiring that they be registered in the name of their real owners, would curb this source of criminality.

Reform proposals have been dogged by bankers’ complaints about the unnecessary regulations. These complaints have survived the damage under-regulated banks have done: ‘Wholesale capital markets’, the bankers declare self-righteously, ‘contribute to the efficient allocation of capital. International banks match savers and borrowers across the globe, reducing funding costs, facilitating cross-border investment and financing trade.’24 It is considered politically impertinent to question this celebration of banking benefactions, so productive of well-deserved profits. In truth, the reform measures proposed, and the even fewer of them enacted, have been palpably insufficient to attain their aim of making banks resilient to shocks. This is because they have not been part of a broader strategy of economic reform.

Banks should be obliged to hold mortgages for a minimum period; financial innovation should be controlled; the flow of footloose capital around the world should be restricted. But such reforms will not be possible without a lessening of the social reliance on bank credit. The economy doesn’t work well for the average person, who then has to resort to borrowing to fulfil customary expectation. A more stable economy is the key to safer banking. The neo-liberal project of removing the state from economic management has made economic life less secure; the result of which has been a more speculative financial system. The unsettled question is whether financial regulation can be made sufficiently global to support a global financial system.

I have suggested that the deeper cause of the banking collapse of 2007–8 was the growth of inequality. A big expansion in the ‘financial circulation’ (debt) had been required to sustain mass consumption and to speculate in risky assets in the face of falling real earnings and yields. There is little evidence that these trends have been reversed.

In a cryptic letter to T. S. Eliot in 1945, Keynes envisaged three possible forms post-war economic policy might take:

. . . the full employment policy by means of investment is only one particularly application of an intellectual theorem. You can produce the result just as well by consuming more or working less. Personally I regard the investment policy as first aid. In U.S. it almost certainly will not do the trick. Less work is the ultimate solution (a 35 hour week in U.S. would do the trick now). How you mix up the three ingredients of a cure is a matter of taste and experience, i.e. of morals and knowledge.25

In writing this, Keynes took the standard view that there is no ‘optimum’ rate of investment for any community. It depends on how wealthy it already is. Neo-classical economic theory tells us that the scarcer the capital stock, the higher the rate of return to capital investment. So poor countries should consume less and save more. Present sacrifice will earn future reward. The moral for rich countries would seem to be the opposite: save less, consume more, work less and learn to enjoy life. Nirvana is the state of not wanting more than one already has.

The nineteenth-century idea of the ‘stationary state’ was based on the notion of capital saturation. It envisaged a situation in which there were constant ‘stocks’ of people and capital, and therefore the economy simply reproduced itself. In the pessimistic version of Ricardo, the declining marginal fertility of the soil brings growth to an end long before human wants are satiated. Efficiency in production could delay the outcome, but not avert it. The ‘limits of nature’ argument of modern ecological economics is a contemporary version of Ricardo’s argument, though one projected from a much higher base of affluence.

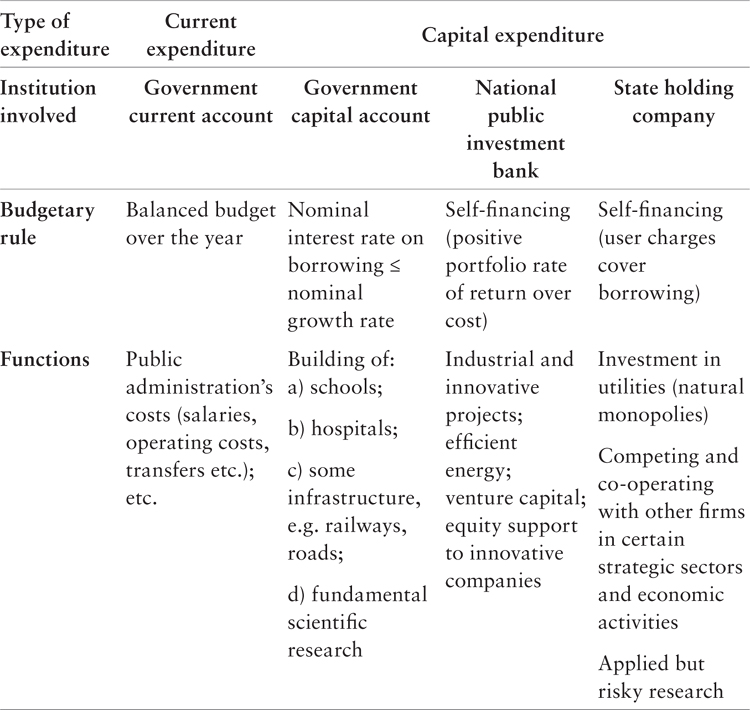

Figure 67. GDP growth in the OECD26

In the optimistic version of John Stuart Mill, echoed by Keynes in his 1930 essay ‘Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren’, and shared by John Hicks, the stationary state comes at the point of saturation of human needs. This kind of stationary state was desirable because it would free humanity from the burden of toil. In Keynes’s vision, the mores of society would no longer be driven by the need to accumulate capital: for the first time in history most people would be able to devote themselves to the ‘art of life’ rather than to the ‘means of life’.

In the last thirty years the average growth rate of rich societies has slowed down, as Figure 67 shows. In the standard growth model, this reflects a decline in the rate at which the advanced countries are adding to their capital stock. Superficially this suggests that Western societies are approaching their ‘bliss point’. Growth deceleration should be regarded not as a problem, but as a culmination. It is possible to interpret the ‘stagnation’ of Japan as the social choice of a rich society.27

However, a more pessimistic view is taken by modern ‘secular stagnation’ theorists such as Paul Krugman and Larry Summers.28

For Krugman, ‘persistent shortfalls in demand’ for new capital goods are to be explained by the increasingly skewed distribution of income. Because the rich save more of their incomes than do the poor, there will be a persistent tendency, in capitalist societies, for saving to ‘run ahead’ of investment, causing Keynesian under-employment. The remedies are public investment programmes and income redistribution. The former can plug the investment gap; the latter the consumption gap. Time will determine the relative weights to be attached to the two remedies.

Like Krugman, Larry Summers denies there has been a secular collapse in productivity growth; i.e. that rich societies today are close to the ‘saturation’ or ‘bliss’ point identified by Mill and Keynes. If, in fact, human wants are insatiable (as most economists believe), the bliss point is bound to be a moving target: the more people have, the more they want. It is just that capitalism, as presently organized, prevents most people from having what they want. Summers attaches particular importance to the ‘hysteresis’ produced by the collapse of 2008–9 (see p. 239). Thus the theory of secular stagnation is a contemporary version of under-consumption theory.

Market optimists regard the problem as spurious: technology and globalization will keep growth in line with expanding consumer wants, if unfettered by government restrictions. Market pessimists would urge a substantial redistribution of wealth and income from the rich to the poor, both on grounds of social justice and to lessen reliance on debt-fuelled growth.

Optimists and pessimists alike abstract from the problem of automation. Yet Keynes foresaw in 1930 that automation would reduce the demand for human work. As he put it, we will need to ‘spread the bread thin on the butter – to make what work there is still to be done as widely shared as possible’.29 The state’s task would be not to guarantee full employment in the current sense, but to enable an orderly transition to a shorter working week: this was the point he made in his letter to Eliot in 1945.

Keynes’s prediction hasn’t yet materialized, but he may be right in the end. In the past, new technology made some jobs obsolete, but simultaneously made other workers more productive.30 Likewise, it created, and is still creating, whole new areas of work such as web design, hi-tech engineering, programming, data analysis and so forth. An ageing population will require more looking after. But now machine intelligence is improving at such a rapid rate that the distinction between capital and labour is blurring. New technology may, indeed, create as many jobs as it destroys, but the new workers will be machines, not humans. For the first time in history, human labour may be being made redundant faster than new human employment is being found for it; i.e. the ‘technological unemployment’ predicted by Wassily Leontief in 197931 may be turning into a reality.

If this turns out to be the case, the income equalization which can serve the narrow purposes of the modern secular stagnationist will need to become an essential ingredient of policy in the future. Workers displaced by machines will need to be guaranteed a replacement income. An unconditional basic income guarantee, financed by taxation, will probably be needed in the transition to a less work-intensive future. This raises a whole host of problems which are beyond the scope of this book, but should not be irrelevant to the design of long-term macroeconomic policy.

In the early 1990s it was usual to say that the world economy was ‘reglobalizing’, or returning to its pre-1914 condition after a seventy-year protectionist detour. Three developments have shattered this optimistic prognosis. The first was the unexpected financial meltdown in East Asia in 1997–8, which, following the Mexican peso crisis of 1995, highlighted the instability of global financial markets and the inadequacy of the world’s financial architecture. Second, were the mass protests in Geneva in 1998 and Seattle in 1999 against the setting up of the World Trade Organization (WTO). These marked the start of a popular insurrection against globalization. Insofar as the loose coalition of economic nationalists, anti-capitalists, environmentalists, anarchists and trade unionists had a coherent message, it was that the WTO transferred power from elected governments to multinational corporations. It was a predominantly rich country protest against free trade, though often couched in terms of Western big business exploiting poor countries.32 The third event was the even more unexpected collapse of the developed world’s ‘mature’ financial system in 2008. This sharpened the sense that globalization was harmful to rich countries. Since the Great Recession of 2008–9, these anti-globalist stirrings have splintered and morphed into populist movements of both right and left. Globalization has, in reaction, created global populism.33 Our political language finds it hard to keep up. There is still a political divide between right and left, but it is increasingly overshadowed by one between nationalism and globalism.

Twenty years or so ago it was usual to think of globalization as a unified process involving not just economic/technical but also political/cultural transformation. The internet was conceived as the decisive game-changer in both spheres. By changing the technical means by which people communicated with each other it would change the way they related to each other. Now it is increasingly recognized that economic/technical change has been racing ahead of political/cultural change. This explains the upsurge of old-fashioned nationalism.

The globalist typically wants culture to adapt to the imperatives of economic interdependence, and is surprised and disappointed when it hits back in discordant, often ugly ways. France’s President Emmanuel Macron has described populism as the politics of those ‘left behind’. This is right, as long as it is recognized that the feeling of being left behind is not just economic, but also cultural. At heart the globalist thinks of anti-globalist feeling as a social pathology, which needs to be explained, rather than as a reasonable response to what, for many, are distressing events. Globalists demand that people adapt to seemingly irreversible economic changes, without understanding that it is a mutual adaptation which is needed. Societies have very strong adaptive capacities, but they are not infinitely malleable, like bits of putty.

Thus it would be wrong to see anti-globalization as just fuelled by economic discontent. Sociology, anthropology and history have been undermining the economist’s understanding of human nature. Homo economicus, the man who lives for bread alone, has given way to a more complex understanding of the human as a social animal for whom belonging and eating are interconnected elements of being. Hence the rise of identity politics is not just a protest against job losses, declining wages and rising inequality but – just as importantly – a protest against cultural changes which are robbing people of their need for the familiar and normal. An economics which both minimizes the possibility of non-material forms of flourishing and fails to deliver its own promised goods is ripe for populist demolition.

Donald Trump is the most important populist to have won high office so far (Viktor Orbán, prime minister of Hungary, is the most important European populist in power), but popular opposition to the free movement of goods, capital and labour has stopped globalization in its tracks. Trade and capital flows have recovered from the 2008–9 crisis at about the same pace as output, but no faster. There has been no multilateral trade agreement since 1993; instead there has been a proliferation of bilateral deals. Trump promises to scrap the North American Free Trade Agreement of 1992, and the Trans-Atlantic and Trans-Pacific trade treaties conjured up by President Obama. He announced tariffs on imports from China and the EU in what could well be the opening shots of a new trade war. Capital movements are being restricted de facto on security grounds. Free movement of labour is curtailed in North America and Europe. The most astounding reversion to national economics was the British vote in 2016 to leave the European Union.

The kernel of the problem is that the market system lives by generating systemic upheaval, not just in economic but in social relations, as Marx recognized. Out of the upheaval comes a better life – or so it is claimed. But along the way there is a great deal of human breakage, and in the short-run many losers. That is why a market system, to be generally acceptable, requires a state to curb its excesses, distribute its fruits in an equitable way, and mitigate its hardships. National states were created to do this; they in turn created and enabled unified domestic markets. We have been trying to create a unified global market by diminishing national states without setting up a global state, or even recognizing the need for one. No wonder there has been an explosion of popular resistance.

Karl Polanyi brilliantly analysed the emergence, in the nineteenth century, of the simultaneous double movement towards greater marketization and state protection against its consequences, the numerous Factory Acts of the early industrial revolution, to protect children and limit hours of work being one of his main examples. The first great age of globalization in the late 1800s saw the extension of this double movement: the growth of the international market led to the birth of welfare states, the restoration of protective tariffs, and the establishment of central banks to minimize financial crises.

However, such national defences against the consequences of globalization were never incorporated into a rule-based international order. Its absence brought the first age of globalization crashing down in 1914. Following the disintegration of the world economy in the 1930s, Allied victory in the Second World War led to the setting up of a more robust set of international institutions and rules, the socalled Bretton Woods system, to underpin a revived liberal market order. Significantly, it allowed, while seeking to relax, the protective national controls over the transnational movement of trade, capital and people left over from the 1930s. What was set up was an ‘embedded’ liberal trading system as an international counterpart to post-1945 Keynesian social democracy in domestic politics. It fell far short of providing an economic government of the world, however, just as the United Nations failed to provide a political government. In practice, the United States acted as a kind of surrogate government for the free world in both economics and politics (just as the Soviet Union did for its own sphere). The surrogate was more or less legitimate because US hegemony was partly disguised and America provided services deemed indispensable by its beneficiaries. This liberal mix of national leadership, international institutions and markets, backed by hard power where necessary, provided a solidenough basis for peace and prosperity for thirty years.

The unrepentant resurgence of globalization was made possible by capitalism’s triumph over communism. Although in the 1990s the Soviet Union failed to match the economic performance of the capitalist West, for many years the appeal of communism checked the power of the business class. But, since 1990 neo-liberal statecraft has been unchallenged. It scrapped or emasculated the protectionist features of the post-war order which made it politically acceptable. Enslaved by utopian theories and ignorant of history, the ideologues of the free market have been preparing the ground for the Apocalypse.

The conflict between cross-border economic integration and national systems of politics is at the heart of Dani Rodrik’s intriguing notion of the ‘impossible trinity’. He contends that democracy, national sovereignty and economic integration are mutually incompatible: we can have any two of them, but not the three together. National sovereignty can be combined with economic integration if there is no democracy – as happened in the nineteenth century because there were too few voters to protest against it. We can have national sovereignty and democracy at the expense of economic integration. Or we can have economic integration and democracy together, provided we have democratically accountable supra-national institutions. The argument is over-stylized because at all times rulers have had to pay attention to their people, and most nineteenth-century states were protectionist. The value of Rodrik’s exercise is to challenge the conventional wisdom that economic integration is irreversible. His trilemma offers an explanation of why the first wave of globalization was rolled back in 1914, and warns of disaster if we persist in global fantasies that are not anchored in the realities of nation states and their voters. Economics has gone global but politics remains national. The contradiction between the two domains of action explains the rise of populism. Either we create an international social contract or nationalist economics will return.

The European Union is a model of a currently failing effort at economic integration. The Treaty of Rome of 1957 committed the founding states to the ‘Four Freedoms’ – freedom of movement of goods, services, capital and labour. These are the building blocks of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU), and are held to be indivisible. To enshrine them at the heart of the EU signified the ambition of its founding fathers to create a state, or ‘political union’. But the state has not arrived. The competences of the EU’s central institutions, the scope of its rules, have been constantly expanded, but their accountability has not kept pace. Instead of democratic accountability there are rules against money creation, fiscal deficits, unfair competition and so on. But strong rules and weak states are a contradiction in terms. Complaints about the ‘democratic deficit’ have been growing and have exploded in powerful anti-European populist movements.

The rules started to crumble as soon as they were put to the test in 2008–10. The jewel in the EMU’s crown was the Single Currency Area, started in 1997. Paul de Grauwe has identified its two main design faults: the lack of a fiscal transfer mechanism, and the lack of a lender of last resort for the banking system. As a result, liquidity crises have spilt over into solvency crises, and solvency crises into sovereign debt crises.34 ‘This dynamic can force countries into a bad equilibrium characterised by increasing interest rates that trigger excessive austerity measures, which in turn lead to a deflationary spiral that aggravates the fiscal crisis.’ The only remedy, de Grauwe argues, is a ‘budgetary union’. By ‘centralising part of the national budgets into a common budget managed by a common political authority, the different increases in budget deficits . . . translate into a budget deficit at the union level’ in time of recession. But the ‘common political authority’ needed for such a construction is ‘far off’.35 De Grauwe’s two design flaws can be reduced to one: the lack of a legitimate state. Keynesians spotted the flaw in this reasoning from the start.36

Political Union (otherwise a state) was always expected to be built alongside the Economic and Monetary Union. Indeed, the more cynical, or realistic, Europeanists saw the inevitable crises of the EMU as spurs to state-creation – a huge gamble that the integrative forces would prove more powerful than the distintegrative ones.

Today the future is in the balance. In response to the crisis, and its populist reactions, the Commission has proposed a European Monetary Fund and a European Finance Minister as the next instalment of statehood. But the Germans are opposed: they prefer risk prevention by strict rules to risk sharing through monetary and fiscal transfers, understandably from their point of view, since most of the risk will be transferred to them. They oppose a fiscal union for the same reason. A European Finance Minister without a usable budget is a symbol of futility.

Few of the sensible reforms needed to make the EU, and especially the eurozone, work well are feasible, because of the particularly rigid way they have been set up. Paradoxically, the working of this fixed-rule system depends on discretionary action by its leading member, Germany, which has the position, but not yet the outlook, of a Kindlebergian ‘underwriter’.

To the threatened implosion of the world’s most ambious experiment in stateless economic integration there are two possible reactions: ‘One’, writes de Grauwe, ‘is to despair and to conclude that it would be better to dissolve the monetary union . . . The other reaction is to say, yes, it will be very difficult, and the chances of success are slim, but let’s try anyway.’37

What Professor de Grauwe fails to explain is how the Eurozone came to be constructed with such a palpable design flaw. The standard answer is that it was part of the political deal that allowed the reunification of Germany. But just as importantly it reflected the view of neo-liberal economics that markets needed rules, not states.

The general presumption in favour of free trade has rarely been questioned since the nineteenth century. Tim Congdon does not beat about the bush: ‘Free trade is good for you,’ he tells us. ‘Nations that adopt it . . . develop and prosper: they outperform nations that restrict imports and limit contact with the rest of the world.’38 This is bad history, since many nations have prospered under Protection.

Protection is currently defined as ‘the setting of trade barriers high enough to discourage foreign imports or to raise their prices sufficiently to enable relatively inefficient domestic producers to compete successfully with foreigners’.39 The roots of this definition in the doctrine of comparative advantage are clear enough. The Protectionist would say that the primary duty of a government is to protect its own people from danger and misfortune. To do so while benefitting others is best of all. This was Adam Smith’s powerful argument for free trade. But a government is not elected to promote the ‘welfare of the world’ at the expense of its own people. If it tries to, it will soon feel their wrath. Running through the free trade argument is the conviction that free trade is best in the long-run. It forgets that what happens in the short-run can blight the lives of a generation and, beyond that, those of their children.

There are seven main arguments for Protection:

1. The ‘infant industry’ argument, which we have already encountered (p. 89). Friedrich List rejected the static nature of Ricardo’s theory. Initial conditions need not be final conditions. Comparative advantages could be consciously created by state policy by steps to foster initially uncompetitive manufactures. Ha-Joon Chang puts it graphically: ‘had the Japanese government followed the free-trade economists back in the early 1960s, there would have been no Lexus. Toyota today would, at best, be a junior partner to some western car manufacturer, or worse, have been wiped out. The same would have been true of the entire Japanese economy.’40 List did not think of Protection as a permanent system: after the ‘infant industries’ that he wanted protected had achieved maturity, free trade should be the rule. He forgot though that there is no end to economic development, because technology never stops. Today’s advanced countries are full of industries, both senile and juvenile, clamouring for Protection.41

2. New or Strategic Trade Theory is an offshoot of the infant industry argument. In the standard free trade model, factor endowments – the determinants of comparative advantage – lie outside the model, whereas within the model there are constant returns to scale. New Protectionists like Nicholas Kaldor and Paul Krugman ‘endogenized’ the factors by postulating increasing returns to scale. Put simply, in a world of imperfect competition, starters’ advantage cumulates. Increasing returns are captured by those who are first in the field with a new process or product, making them almost impossible to dislodge thereafter. In principle this can justify Protection for the infant industries of both developed and developing countries.42 This argument, as can be seen, depends heavily on the persistence of monopoly. It makes little sense in today’s world, where being first to build a transport system may lock a country into an obsolete state of the industrial arts.

3. Unemployment. The free trade model assumes full employment both before and after trade. The existence of a state of unemployment therefore provides an argument for Protection. This is a good argument.

4. The free trade case developed by Ricardo assumed that capital was mobile within countries, but immobile between countries. He recognized that if capital were free to maximize profit globally, the theory of comparative advantage would not hold ‘because in that case international specialization will be determined by absolute costs, like specialization in one country’. There would then be no barrier to the depopulation of regions, even whole countries, if their costs were uncompetitive. Ricardo even hoped that men of property would keep their capital at home and be content with a modest profit.43 Commenting on Ricardo’s position, two authors write: ‘[T]his is also a question of the culture of capitalism. The type of “nativist” tradition which Ricardo expresses is no longer in keeping with the conditions of casino capitalism and its world of financial derivatives.’44

Today capital exports are closely linked to the export of jobs via the export of technology. This can force higher-paid workers of the capital-exporting countries to compete with lower-wage labour abroad using the same technology – a competition which will either cost them their jobs or force down their wages. We should not forget that globalization was intended to depress wage growth in the developed world.

5. The ‘strategic industry’ argument. Protection has been advocated to safeguard war-making capacity. By contrast, free trade presupposes the permanent peace which it claims to help bring about.

6. The argument from diversity. Ricardo’s theory required Portugal to concentrate on producing wine, leaving cloth production to Britain. Liberals who rightly value cultural diversity fail to understand that cultural diversity requires economic diversity.

7. Protection as a retaliation or bargaining chip. Tariffs, or their threat, may be used to negotiate ‘fair trade’ agreements. Only a country or group of countries with monopoly stakes in world trade can hope to deploy muscle for this purpose. The United States has often used protectionist tools to get other countries to limit their exports to the USA or reduce their trade barriers. Trump’s Protectionist announcements may or may not be intended to leverage ‘good’ trade deals with China and Europe. The EU has just announced Protectionist countermeasures to Trump’s Tax Cut Bill.45

In the orthodox view, all the valid arguments for Protection are ‘second best’: they presuppose, that is, that the political or economic conditions for beneficial free trade are lacking. But it could be that these conditions are lacking more often than not, in which case there can be no general presumption in favour of free trade.

While free trade remains accepted doctrine, many forms of disguised Protection flourish. Rich countries aim to protect their producers (under the guise of protecting their consumers) by imposing health and safety standards on imported products, or insisting on minimum labour standards for imported goods, often impossible for poor countries to meet. Countries such as China and Germany rely on under-valued currencies to maintain permanent export surpluses, in line with traditional mercantilist statecraft.

The pressure for Protection is growing. The main reason is that domestic protections for the less educated and less skilled have been progressively eroded at the same time as the speculative power of finance has been enlarged. The result is a substantial increase in insecurity. Populists want their own states to do more to protect their populations while at the same time limiting the power of finance to harm them. Traditional American economic nationalism has been reignited by the realization that continued reliance on credit from China and other surplus countries to finance American purchases of their goods is hollowing out the once mighty American economy.

Can political demands for a meaningful national ‘control of our borders’ be met without breaking up the world economy?

In his Clearing Union plan of 1941, Keynes proposed a payments system to make the world safe for free trade. Its main purpose was to prevent countries running persistent trade surpluses. These, as he saw it, imposed deflation on deficit countries, who would respond by slapping on tariffs or depreciating their currencies. The International Monetary Fund, set up in 1944, rejected Keynes’s logic of ‘creditor adjustment’. But as a sop to the British it included, in Article 7, a ‘scarce currency’ clause, which allowed members of the Fund to restrict their purchases of goods from countries whose currency was declared ‘scarce’, i.e. which ran persistent current account surpluses. Debtor countries would also be protected from capital flight by restrictions on international capital mobility. Keynes understood that a good payments system was essential for ‘good’ trade.

Article 7 today could reasonably be invoked by the United States against China and by some members of the European Union against Germany. Cutting its trade deficit with China has long been an aim of American policy, but in the Trump Administration words are being translated more vigorously into action. Following the release of US strategy documents on national security, defence and trade late in 2017, which for the first time defined China as a strategic competitor, Trump imposed import duties of 50 per cent on washing machines, and tariffs of up to 30 per cent on solar panels. And in mid-February 2018 the US Commerce Department proposed the tariffs on US imports of steel and aluminium: 25 per cent on steel and 10 per cent on aluminium; China is the world’s largest producer for both commodities.46

The economist Vladimir Masch has proposed a more coherent strategy of Compensated Free Trade (CFT) for a ‘sensible’ Trump Administration, which, in its essentials, amounts to unilateral activation by the United States of Article 7 of the Bretton Woods Agreement.47 The US Administration would decide on the maximum amount of its desired trade deficit each year. In order to achieve its goal, it would impose limits on the surpluses of each important trading partner. This would chiefly affect China, Japan, Germany and Mexico; of the total $677 billion trade deficit of the US in 2016, China contributed $319 billion, Japan, $62 billion, Germany $60 billion and Mexico $59 billion.

It would then be up to the surplus country to limit its exports to the United States to the required amount. Countries could exceed their ‘quotas’ if they paid the difference between the value of their actual exports and the value of their allowed exports. If they tried to exceed their quotas without paying the ‘fine’, their surplus exports would be blocked.

As Chi Lo summarizes:

In the longer-term, both China and the US seem to be striving for onshoring the globalised production chains built over the past three decades, with China doing it through import substitution to minimise the foreign share of its industrial base and the US via America-first policies. Even partial success of these initiatives could be damaging.48

It is inconceivable that the proposed European Monetary Fund would contain an equivalent of Article 7, allowing, say, Greece, Italy and Portugal to limit imports from Germany, because this would be a major breach in the Customs Union.

In 1941 Keynes, while endorsing the case for ‘permanent’ control of capital movements, went on to say that

this does not mean that the era of international investment should now be brought to an end . . . The object, and it is a vital object, is to have a means of distinguishing (a) between movements of floating funds and genuine new investment for developing the world’s resources; and (b) between movements, which will help to maintain equilibrium, from surplus countries to deficiency countries and speculative movements or flights out of deficiency countries, or from one surplus country to another. There is no country which can, in future, safely allow the flight of funds for political reasons or to evade domestic taxation or in anticipation of the owner turning refugee. Equally, there is no country which can safely receive fugitive funds which cannot be safely used for fixed investment and might turn it into a deficiency country against its will and contrary to the real facts.49