Our theme throughout this book has been that cybersecurity is about people – and that people can be the best asset to protect a business and its information. But information security awareness, behaviour and culture are but one of many competing priorities for both the CISO and the business. Given this fact, and all the constraints we are under, how can we develop, enhance and elevate our ability to deliver the ABCs?

Many guides to awareness programmes have been produced, exhorting the CISO to do this or do that, measure this or measure that. It would be easy to follow precedent and set out such a guide in this chapter. Our approach is somewhat different. Our belief is that the three components – awareness, behaviour and culture – work hand in hand to change people’s attitude, activities and involvement with cyber or information security. So rather than exhorting you to produce new slides, write clearer messages and target your work (which are all certainly relevant and need to be done), we’re going to take a different approach: start with and apply the ABCs to yourselves.

At this point, I hope you are asking why. Why do we personally need security awareness? We are the teachers, the professionals and the experts. Well, before we try to change anything or anybody, we need to look at ourselves. We cannot force people to change or be convincing proponents of change if we haven’t changed ourselves and, most importantly, made those changes ‘stick’. In other words, we have changed our behaviour and have accepted those changes; integrated them into our thinking and our day-to-day activities; and those changes have become long term and second nature. They have become unconscious: we don’t think about the changes, we just do them. Building on our discussion of culture in the previous chapters, I’ll hope you’ll recognise that we have changed our culture as well.

START WITH YOU

To apply the ABCs, we start with ourselves. It is little use to change something if we don’t know where we are starting from, as we won’t know what’s changed. We also start by asking a simple question: what is our culture (or rather the culture of the security function in the business)? How do we behave? What do we say and how do we say it? Much of business is personal, an oft-forgotten fact, and people react and behave according to the people around them. If we as security professionals do not live or demonstrate the awareness, behaviours and culture we want other people to copy and adopt, then we can hardly blame them if they don’t show those very same behaviours themselves. If we cannot understand other cultures and norms in the organisation and try to impose our own culture and norms on top, or in place of those other organisational cultures and norms, then we will fail. In fact, in a large organisation, the sheer number of non-security professionals may be seen to doom us to failure. As an example, one organisation your author has worked at has over 500,000 (yes, over half a million) people working for it globally: the total number of IT and security staff globally was about 1,000; we can hardly dominate, and pushing our culture is a challenge. We will come back to the numbers game later.

When we talk about living behaviours, I’m not saying we should all be rushing around in ‘superhero’ costumes and acting as if we are the guardians of the corporate galaxy. Nor am I saying we need to be like everybody else. To make the ABCs work we need to embody what we say, teach and do. We need to constantly check ourselves and our behaviours and ensure how and what we do sends and reinforces the messages we want. We may have to alter our mindsets and our approach to problems so that we fit in better with the corporate culture and way of doing things. This is very hard, as it requires reflection, feedback and time – and time is often at a premium. It’s also very difficult to change and admit our weaknesses; yet that is a vital part of any change programme. I’m not going to peddle ‘cod psychology’ here with some four-step process to reach enlightenment. Instead, apply the tools and insights in this book – and find out how change works from the experts.

On top of our relentless focus on ourselves, we need to make a long-term commitment to understand the organisational culture, our place in it and to then create our own culture that fits into the organisation yet delivers the cybersecurity the business needs. This is perhaps the most important decision we have to make. It’s easy as a cybersecurity professional to look at an organisation and dismiss the level of security as ‘rubbish’ or ‘just not good enough’. However, the level of cyber (and indeed physical) security an organisation has, needs, should have and what we think it should have may be very different. Factors such as the industry sector (our experience in one sector may not transfer well to another sector), the business understanding and commitment to cybersecurity and the decisions made by the business will all influence the security that is in place and the attitude to cybersecurity. Ultimately, the business that pays for the cybersecurity may have deliberately decided to have a particular level of security. No matter what we think, the business will usually have the final say. A good example is a finance or profit focused organisation where hitting financial targets are the pre-eminent decision-making criteria: anything that pushes up costs, reduces margin, reduces profit and is not seen as core to the business will not receive much support. In terms of the ABCs, we need to cut our cloth accordingly; there is no point in trying to build elaborate schemes if the business doesn’t want them, nor will it support them. This of course comes back to culture and our understanding of the organisation, and how we fit our culture and our norms within the organisation.

So, the ABCs don’t start with glossy new presentations and merch, followed by swift behavioural interventions and the creation of a security culture. They start with us, our behaviour and culture, and an awareness of our place in the organisation and how we fit into the corporate culture. Once we understand that fit between security and the business, and hopefully have made strides ourselves to close any gaps, then we can start the real journey. However much we don’t like it, we have to change to fit ourselves into the existing culture and the business, not the other way round.

The real journey is change. The ultimate results of the ABCs are change: change in and of ourselves and change in non-security people’s perceptions, thoughts and actions so that they perform work (and non-work) activities in what we, as security professionals, consider to be a more secure manner. Change, as discussed, is incredibly hard to make happen and to then take forward.

So, going back to the previous paragraphs, we have to change first. Once we understand culture and have improved our awareness and insights into culture, then we can plan change. It’s tempting to go for big changes and radical solutions; but these may not be the ones that work or stick. Sometimes, it’s better to go small. Small changes are often easier to make and easier to keep going.

FOCUS ON WHY

Instead of rushing in and trying to change anything and everything, we should focus on the simple question posed by Jessica in Chapter 2: why?

If we can answer that question in a convincing and simple manner, then we can start our journey. We shouldn’t try to answer that question on our own; that would be one of the biggest mistakes we could make. Instead, we should ask that question to a representative cross-section of our organisation from top to bottom and use that to help us answer the why. It will also help us to understand what people know, want to learn and want help with; all of which are inputs into the design of a successful change programme. We are raising our awareness – we are focusing our attention on culture and our fit within the organisation and its culture. We’re not trying to change anything yet: remembering the definition of awareness, we’re becoming aware.

Interestingly, awareness is also the first step in some marketing campaigns and forms part of AIDA: awareness, interest, desire and action. The underlying concept in AIDA is that by creating awareness, we can then build interest, create desire and drive action. In fact, AIDA is another tool that is applicable here and across all the ABCs.109

Asking ‘why’ on its own will, in all likelihood, provide us with a dazzling array of answers and many of those may not be actually relevant to the question. We actually need to structure the question slightly more subtly to capture the information we need. We could ask questions such as ‘why don’t you engage with our security awareness programmes?’, ‘why do you have a negative perception of the security function?’, ‘why do you think the information security function is viewed negatively in your department’ – and so on. Asking the reverse – ‘what do you find interesting in our awareness campaigns?’, ‘what do you like about working with us?’ – help us capture and understand the approaches we should be doing more of. These questions, with their open nature and their appeal to the less rational and more emotional side of the individual, should help to capture the insights we need to examine what and how we do things. Don’t be afraid to follow up these questions with further questions such as ‘what makes our programmes dull and uninteresting?’, ‘what would you change?’ to gain further insight. Again, we can focus on the positive – ‘would you like more of this style of training?’, ‘do you want us to attend more project meetings?’ – to balance the insights we gather and help us to build a fuller picture of how and where we are succeeding and how and where we are not. You’ll be surprised at how much people will share because they have been asked, especially if the interview is face to face and the individual is in a junior role.

This may be an extremely uncomfortable exercise – after all, these questions may reveal some pretty harsh perceptions about us and what we do – but it is necessary to fully understand where we are starting from and where we can change. The answers need to be analysed and it may be valuable to bring in one or two individuals from outside the function to help with that analysis and provide a different (though it may not be objective) perspective.

IDENTIFY BEHAVIOURS

Equipped with these insights and some deep thinking about what they mean, we can continue our ABC journey. Now we are aware, we have to translate that into action. We’ve already intimated that it’s best to start small when considering changes: small changes typically are easier to make and thus often will be made; small changes tend to be more ‘sticky’, which means that once the change is made, people don’t go back and undo the change they’ve just made. Think about quitting an addiction or starting exercise. Both require major changes in lifestyle, behaviours and may challenge established social groups and norms, which is why people often find it difficult to make these changes and then keep going. Now think about recycling paper at work. Typically, there are paper recycling points in many offices, so people recycle paper because it is easy to do so and actually is not a major change – instead of throwing it in the bin, you walk the short distance to the recycling point. It’s a small change requiring little thought or effort to perform and then repeat. So again, rather than tell you to radically change your entire function, awareness programmes and the way you do things, we’ll adopt a different tack.

The key approach here is to identify the good behaviours and keep reinforcing them. Everyone reacts better to praise than criticism, so turn that to your advantage. Additionally, the more you reward good behaviours, the elusive positive feedback loop will start to appear: good behaviours are rewarded, which encourages further good behaviours, which are rewarded and so on.

Unwanted or negative behaviours will have to be addressed; they can’t be ignored. As good behaviours become increasingly the norm, it will be easier to spot the unwanted or negative behaviours and deal with them. There will be a tipping point where such unwanted or negative behaviours are spotted by everyone involved and actions taken to correct them.

It can be beneficial to step back and think through the behaviours that we want to encourage or praise and these can be linked back to our ‘why’. We should try to link the behaviours to meeting the why; and try to model what those behaviours look like in practice.

An important concept to use here is the ‘moment of truth’. Jan Carlzon, the CEO of SAS,110 wrote a book quite a few years ago (Carlzon, 1987), in which he described how every time a customer interacts with a service, that interaction allows the customer to form an impression. That impression can be positive or negative – and people tend to share negative impressions. Carlzon proposed that every interaction should be managed to create a positive outcome. This was applied across SAS, which rose to become one of the most admired airlines by its peers at one point. The idea has been picked up and expanded by Proctor & Gamble and even Google to bring it into the consumer goods and internet shopping spaces. In terms of our thinking and behaviours, we can look at the interactions we have with the rest of the organisation and decide how to change the interaction and the associated behaviours to make the outcome positive. It’s more than stopping saying ‘no’ (which is way too simplistic, although it helps); it’s thinking how we change what and how we do things, so that every interaction is positive. That doesn’t mean we solve everything there and then, but if we can’t solve an issue, we take positive steps to do so – even if it is ‘I’ll call you tomorrow and let you know what I’ve found out’ and we do so. This approach shouldn’t be confused with feedback surveys and ‘rate your experience’ approaches, rather it is something more fundamental and behaviour driven.

Once behaviours start to change, culture will start to change as well. Culture, as we have seen, is made up of many things: artefacts, attitudes, practices and shared values. As our practices (behaviours) change, our culture will start to change. It may be imperceptible at first, but once one part of the mix changes, then other changes start to happen.

These changes can be supported by careful intervention to reinforce and change other parts of the culture mix. It’s often said that you set the ‘tone at the top’ and leadership and the way in which senior people behave do set out particular boundaries and styles of behaviour that influence and are copied by other staff.

Key among the relevant artefacts will be the stories – the tales that encapsulate good behaviours and actions that should be emulated. All cybersecurity professionals have a fund of war stories and it isn’t too difficult to pick and share stories that highlight the wanted behaviours.

The CISO thus has a many-hatted role in the security function’s ABC journey. The CISO may be leading the whole initiative, so has to be the leader and cheerleader for the initiative. The CISO may be the embodiment of the changes required, so has to be the role model all of the time (which is a lot tougher than you think); the CISO may also be the coach, helping people through change by rewarding wanted behaviours and spotting unwanted behaviours; and, if the ABC journey is being led by another staff member, the CISO may be part of the team.

It has often been said that cybersecurity is ‘a marathon, not a sprint’. The ABCs are a marathon and it is fair to say that there is no defined end; organisations change, as do their culture(s), so the security function has to be able to change with the organisation. The security function should regularly check using the ABCs that they are still aligned to the organisation. When we come to apply the ABCs to the wider organisation, we are most definitely going to be involved in a classical marathon.111

Of course, there is another reason for going through the ABCs ourselves. It is so much easier to lead change, explain change and make change happen if you have been through the process and have experienced the effects of change yourself. We can apply what we have learned to our security awareness programmes to make them more effective and to start the ABC journey for the organisation.

Applying the ABCs

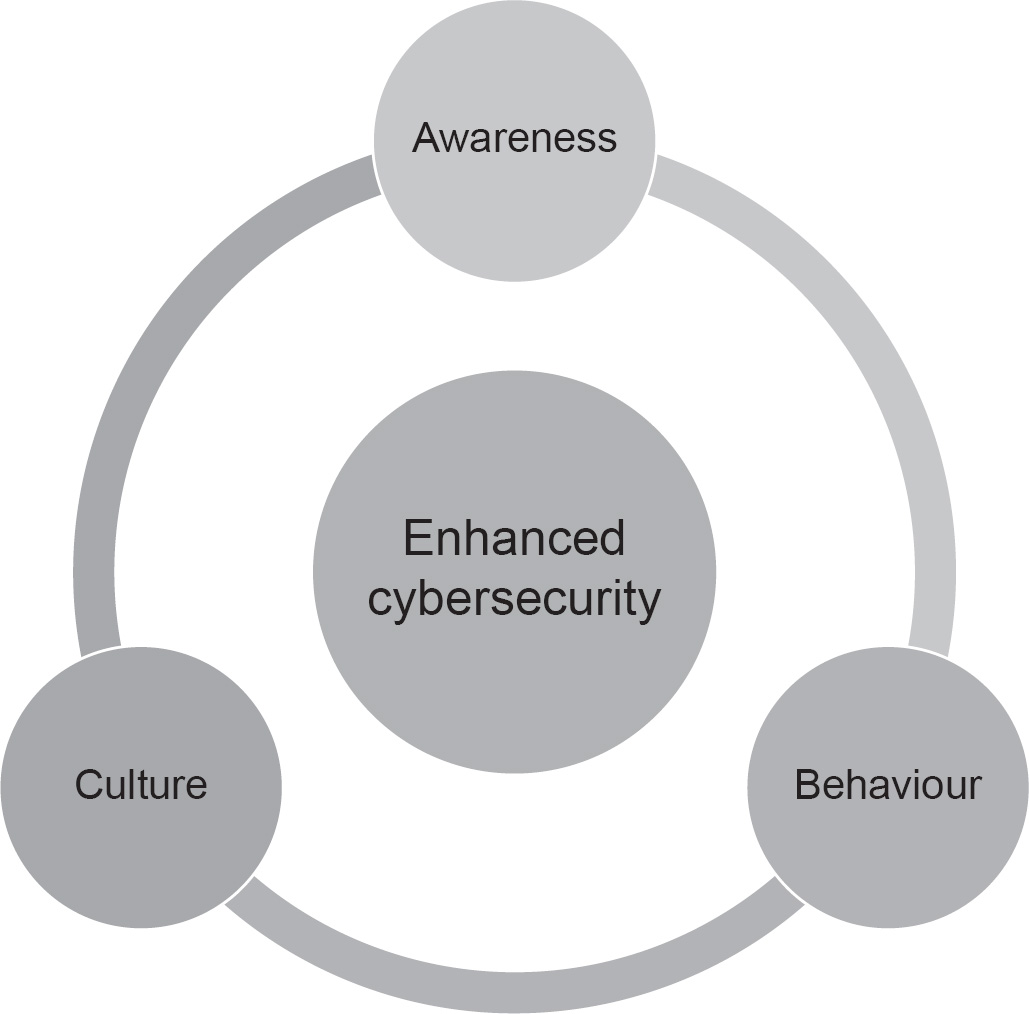

At the start of this book, we displayed the ‘ABC wheel’ and we pointed out that the three components (awareness, behaviour and culture) are intimately linked (Figure 8.1).

Figure 8.1 Simple cybersecurity ABC model

When it comes to applying the ABCs to the organisation, the guiding principle as mentioned earlier should be to start small. I have said that you won’t be exhorted to produce new slides, write clearer messages and target your work. Instead, before you start, write down what you want the awareness message, programme, project, communication or presentation to actually achieve.

Using the ‘ABC wheel’ in Figure 8.1 reminds us that when we set out to create an awareness message, we should consider its impact on behaviour and culture; likewise, we should consider the impact of current behaviour and current culture on that awareness message. A moment’s reflection, for example, on how language is used – a cultural artefact as you may remember – will help you to choose the right words in your message, or the right headline for a particular slide. Further reflection on the behaviour you are trying to change may lead you to a more positive message and, perhaps, an appeal to the more emotional perspectives of your staff.

Let’s go through two practical examples where we can use the ABCs and their integration to create awareness messages (Table 8.1).

Table 8.1 Planning templates incorporating the ABCs

Using a template such as that shown in Table 8.1 (or a similar template), we can start to sketch out a particular application of the ABCs for a particular topic. The template can be expanded to include the tools and techniques we have discussed in this book.

Building a security culture

There is still one question or point I haven’t addressed. How can we build the ‘security culture’ we all, as cybersecurity professionals, believe to be critical to protecting organisational information?

The answer is: we can’t.112

What you can build, with some success, is twofold: first you can introduce and integrate security into the current culture; second you can build a security sub-culture in one or more defined groups of people.

The first point of success, introducing and integrating security into the current culture, relies heavily on understanding the organisational culture and injecting symbols, artefacts and stories into the cultural milieu. Security champions and ‘satisfied customers’ can be just as useful as senior executives in telling stories, setting out acceptable behaviours and reinforcing ‘the way we do things around here’. These individuals can, through personal example and action, bring cybersecurity to the desk and make it a living, real thing, rather than a dry, slideware subject. These individuals also help us to beat the numbers game mentioned earlier; in large organisations, the cybersecurity function can’t be physically present much of the time (there are just too many things to do!), so these individuals extend our reach, extend our influence and provide a point of presence in a way we can’t do ourselves. Time spent working with these individuals can introduce stories, behaviours and norms into the workplace that help to enrich and change the culture in small, yet meaningful ways.

There is much the security function can do as well. Obviously, having been through our ABCs and delivering those positive moments of truth and behaviours, we’ll be much more integrated into the culture ourselves. This should allow us to design and use the right stories and artefacts, alongside our presentations, to enrich and change the culture as we’ll be using the norms, the language and the approach recognised by the culture. Importantly we can then back those changes with our behaviours.

Just because it’s very difficult to change the culture as a whole, it doesn’t mean you can’t change a sub-culture, our second point of success. Organisational culture is made up of many things and there may be sub-cultures centred on certain departments or functions. One of these departments or functions may have a security or data ‘consciousness’, in that they handle sensitive data or work with particular clients who require information to be protected. These functions may already have a security culture in some sense and can be very fertile ground for the creation of a cybersecurity culture. Applying the ABCs and working with the individuals in the team to define and then create change through tailored messages and activities should embed security further into the sub-culture and help the team to raise their game (or ensure they don’t slip back). Such an approach focuses cybersecurity resources to protect sensitive information and positions cybersecurity nicely as the team who helped.

FINAL THOUGHTS

There is no magic bullet in cybersecurity, however much we as security professionals wish there was. Despite our increasing reliance on technology and information in all its forms, the overall level of education about technology and security is still very low.

Organisations and cybersecurity professionals are faced with this lack of understanding and are compelled to address it. Security awareness is the key tool we have to deal with this lack of understanding, yet it is imperfect for many reasons.

Our perspective – and one we have set out in this book – is that we can improve security awareness and other related initiatives by taking a step back and considering not just the narrow ‘issue of the day’ but the context – the culture and behaviours of an organisation – in which awareness is used and in which we try to provide education, training and activities to perform.

The ABCs are very much a people-driven approach. People are still the biggest issue and the biggest solution we have. Not to approach cybersecurity from their perspective is to deny ourselves one of the key success factors we have.