The Terrain and Site

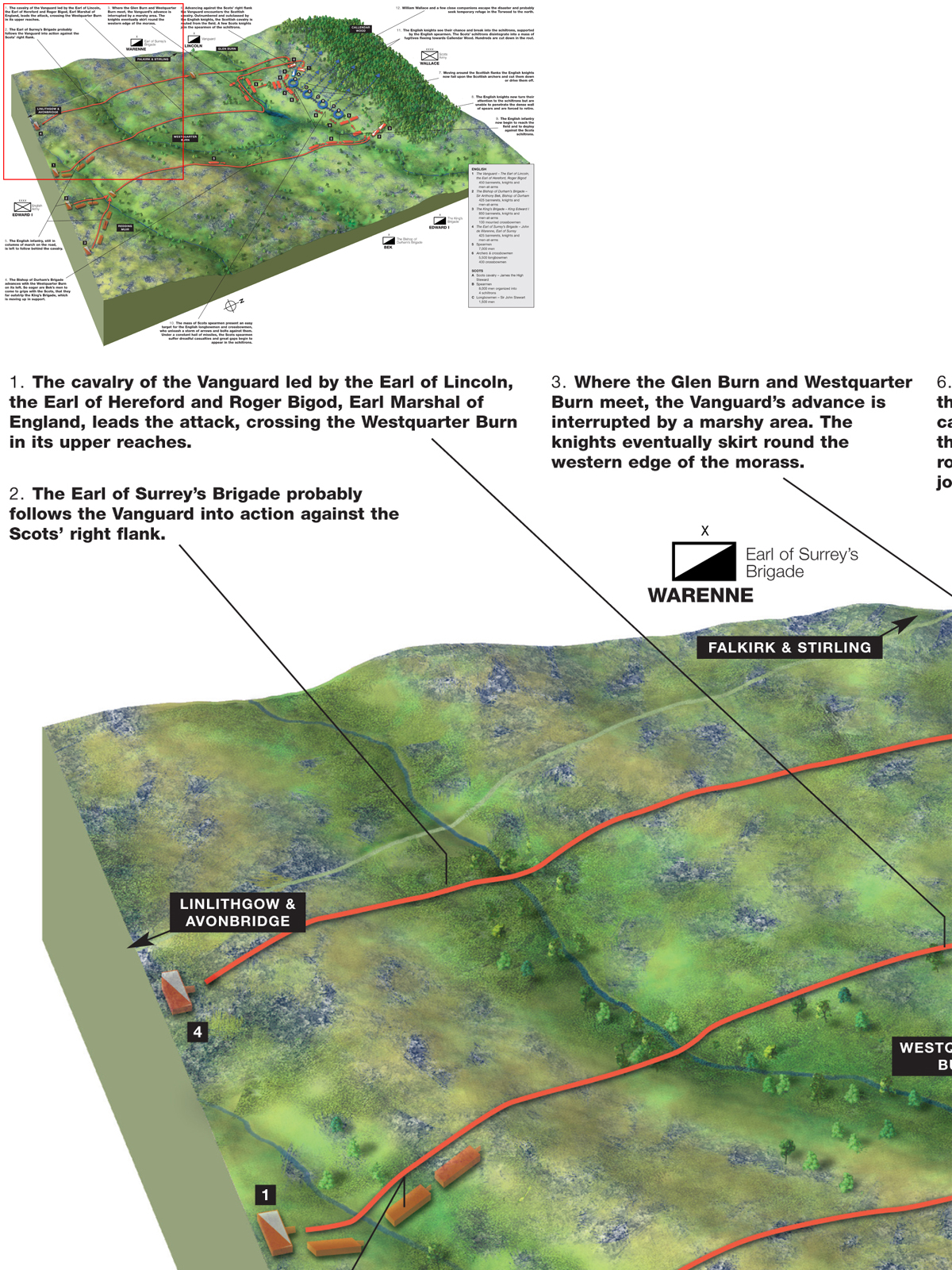

The site of the battle of Falkirk is not marked on Ordnance Survey maps of the area as there is no agreement on its location. The landscape around Falkirk is not characterised by strong geographical features, much less by the landmarks that so clearly define the site of the battle of Stirling Bridge. Nor are the contemporary chronicles very illuminating. Guisborough, who provides us with the most information says only that the Scots were formed ‘on hard ground and on one side of a hillock, next to Falkirk.’ The Scalacronica of Sir Thomas Gray says even less, ‘they fought on this side of Falkirk’ and the Westminster chronicler writes of ‘the plain which is called Falkirk’. The known facts can be made to fit a number of sites, traditionally the site was considered to be north of the town but more recent opinion has inclined towards the south. One possible site is at Glen Ellrig, on the River Avon, although it is rather far south of the town for a battle fought there to be called the battle of Falkirk, the site fits the facts, if, as Blind Harry would have us believe, the English army camped on Slamannan Muir on the night before the battle.

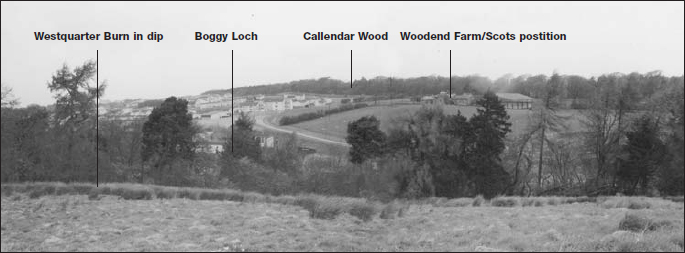

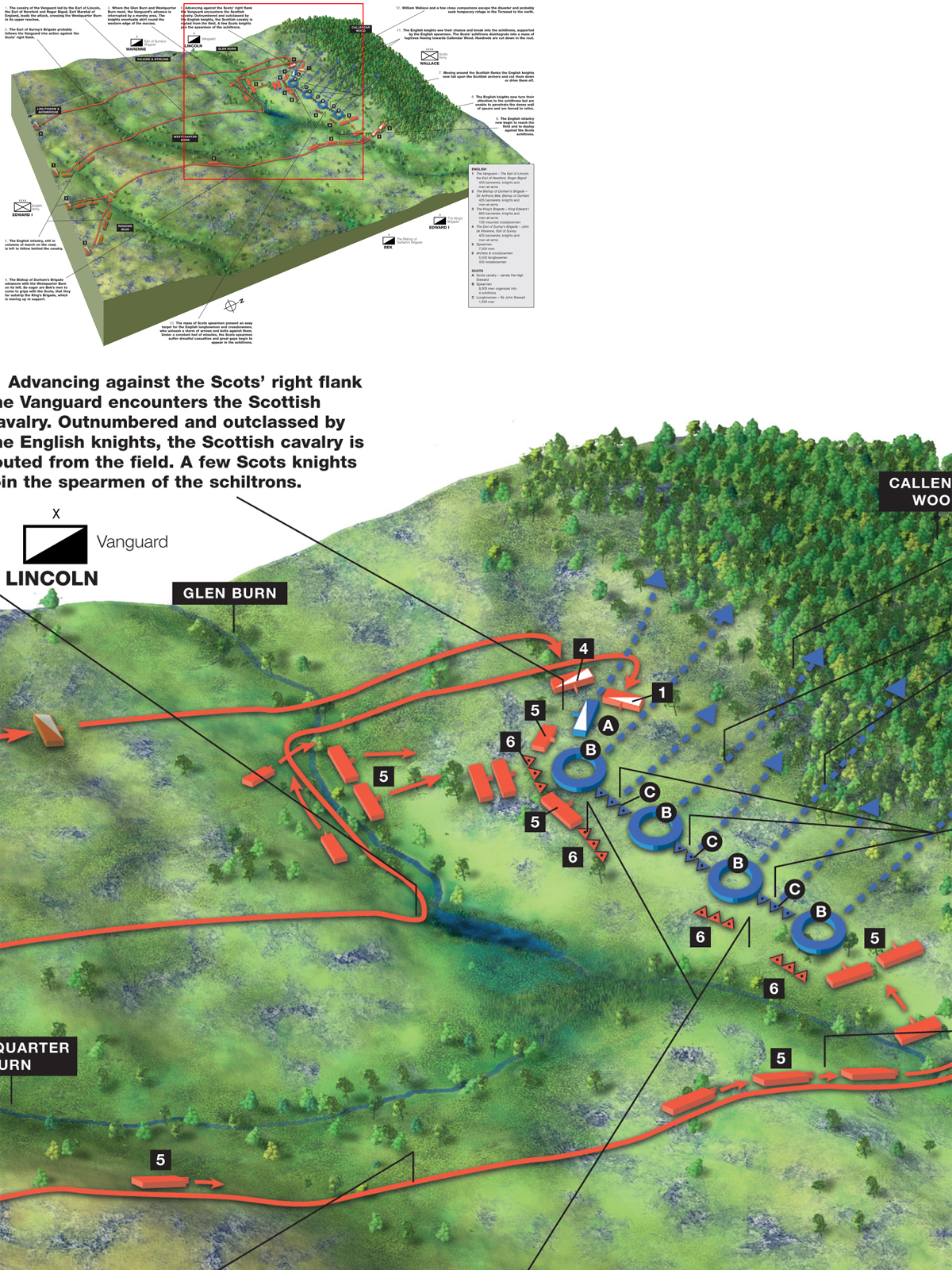

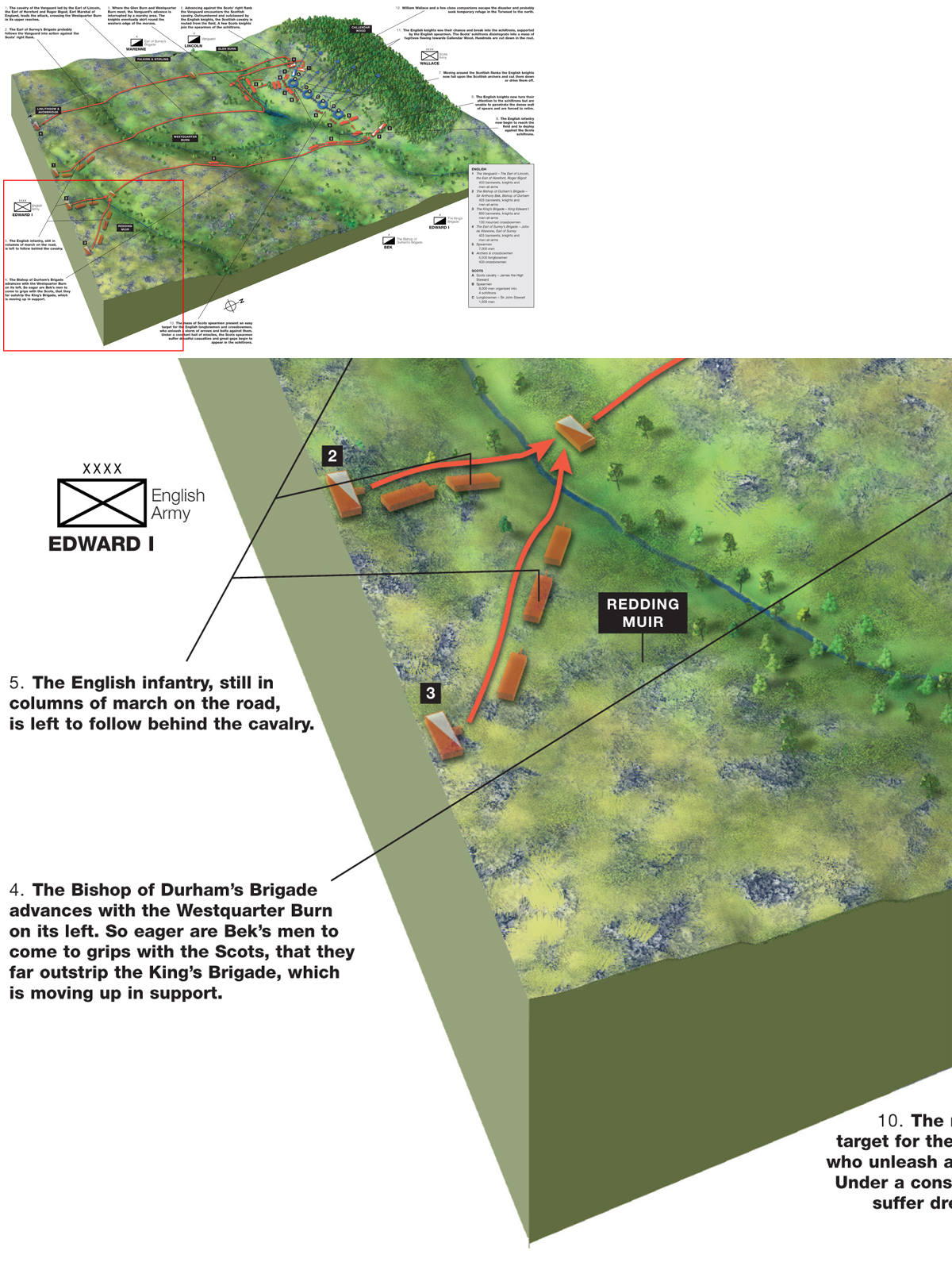

The most probable route of the English army from Kirkliston, and one that agrees closely with Guisborough’s account, is by way of Winchburgh towards Linlithgow, where they camped nearby on the Burgh Muir. Before dawn the army crossed the River Avon near Manuel Priory, passed by Hayning Castle, then took to the high ground by way of Maddiston and the track along the ridge towards Redding Muir which may have been where ‘they saw many spearmen on the brow of the hill.’ At first light, from this vantage point, they made out the Scottish army in the distance, just over a mile away to the north-west. Their position was on the south-east facing slope of a hillside above the Westquarter Burn with an impassable bog below in the valley bottom that had formed at the confluence of the Westquarter and Glen Burns. Behind the Scots position were the woods of Callendar and further beyond was the town of Falkirk. The bog was certainly an obstacle but could be avoided easily enough simply by skirting round it. It was not part of the Scottish defensive position. The open slopes above, where the schiltrons stood, were firm ground and offered no impediment to the heavy cavalry. The lay of the land, in particular the rather steep bank rising from the boggy area, invited a flank attack. Callendar Wood, to the rear of the Scots, would have offered an escape route in case of defeat, otherwise there seems to be no obvious defensive advantages to the position. By opting to fight a defensive battle Wallace had surrendered the initiative to Edward without the compensating advantage of a strong position. We don’t know for what reason Wallace decided to fight at Falkirk but there is a strong possibility that he only became aware of Edward’s advance from Kirkliston when his scouts (or perhaps the spearmen whom the English had mistaken for the Scottish army) brought the alarming news that the enemy were nearby on the ridge of Redding Muir. Wallace would have realised then that somehow the fog of war had allowed Edward to steal a march on him. By then it would have been too late to retreat, a move which in the face of the advancing cavalry would have invited disaster, there was only time to form the schiltrons, not on ground that Wallace would have chosen to fight on, but in the best position available in the circumstances.

The advance of the Earl of Lincoln’s vanguard was delayed by a boggy loch in the bottom of the valley beyond the railway. The site of this is apparently no more visible today from the slopes above the Glen Burn than it was in 1298. (author’s photo)

The upper reaches of the Westquarter Burn where the English vanguard crossed followed by the fourth brigade of cavalry under the Earl of Surrey. (author’s photo)

The Westquarter Burn east of the junction with the Glen Burn. It was in this area that the Bishop of Durham’s brigade crossed the Burn and the altercation with Ralph Basset took place. (author’s photo)

Walter of Guisborough’s graphic account of the battle of Falkirk is the most detailed and accurate contemporary one we have; it has an internal consistency and the facts that we can check against other sources, such as the names of the commanders of the English cavalry brigades and the presence of Ralf Basset in the Bishop of Durham’s brigade, are confirmed by the Falkirk roll and other documents. Guisborough’s information came from someone well-placed and close to events, almost certainly an eyewitness, perhaps a banneret or knight of the household or a cleric in royal service. Several prominent Yorkshire knights fought at Falkirk and may have told Walter their tale. The Lanercost chronicle account is short and so is that of the Scalacronica; they contribute only the odd additional detail. Other chroniclers follow Guisborough’s account word for word. Walter Bower, writing later, astonishingly, blames Robert Bruce for the defeat and Blind Harry’s versifying weaves a tortuous tale that leaves Wallace the victor. My account incorporates the landscape features of the Westquarter Burn site with the account of Walter of Guisborough, which it follows closely.

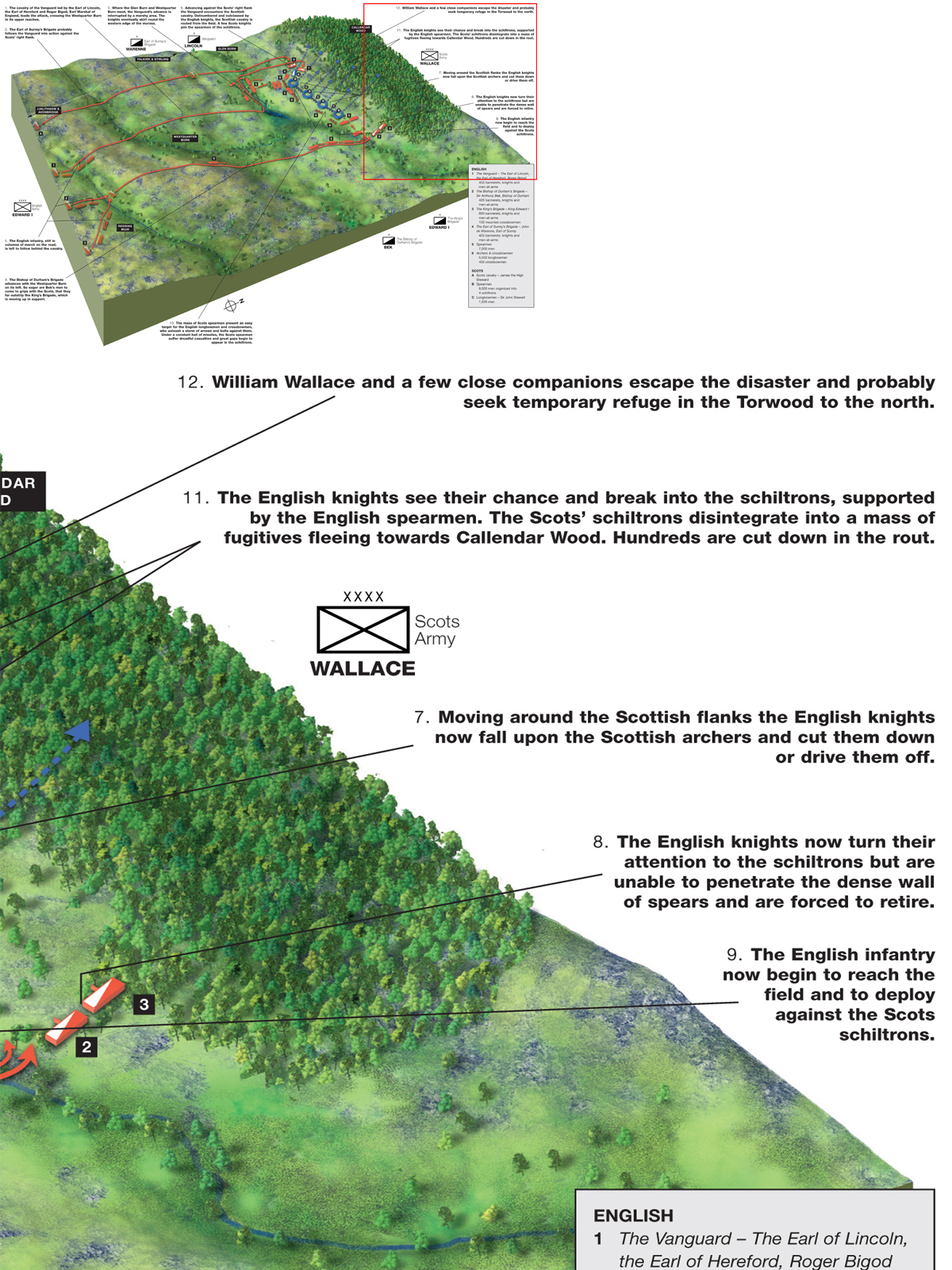

In the grey light of dawn on 22 July the vanguard of the English army, after a pre-dawn march from their encampment on the Borough Muir near Linlithgow, at last caught sight of the Scots. On the crest of Redding Muir, ahead of them and on their line of march, appeared a large body of spearmen. Believing that the whole Scottish army was in position on the ridge beyond, the English hastily formed into battle order and advanced up the slope ahead, but, on cresting the ridge they found no sign of the enemy. They halted and a tent was set up to serve as a chapel; it was the day of the Magdalene, and the King and the Bishop of Durham celebrated a mass in the saint’s honour. By the time the sacred rites were over the day was beginning to brighten and the men could see more clearly. In the distance, just over a mile to the north-west, the Scots could be seen drawing up in battle formation and preparing to fight.

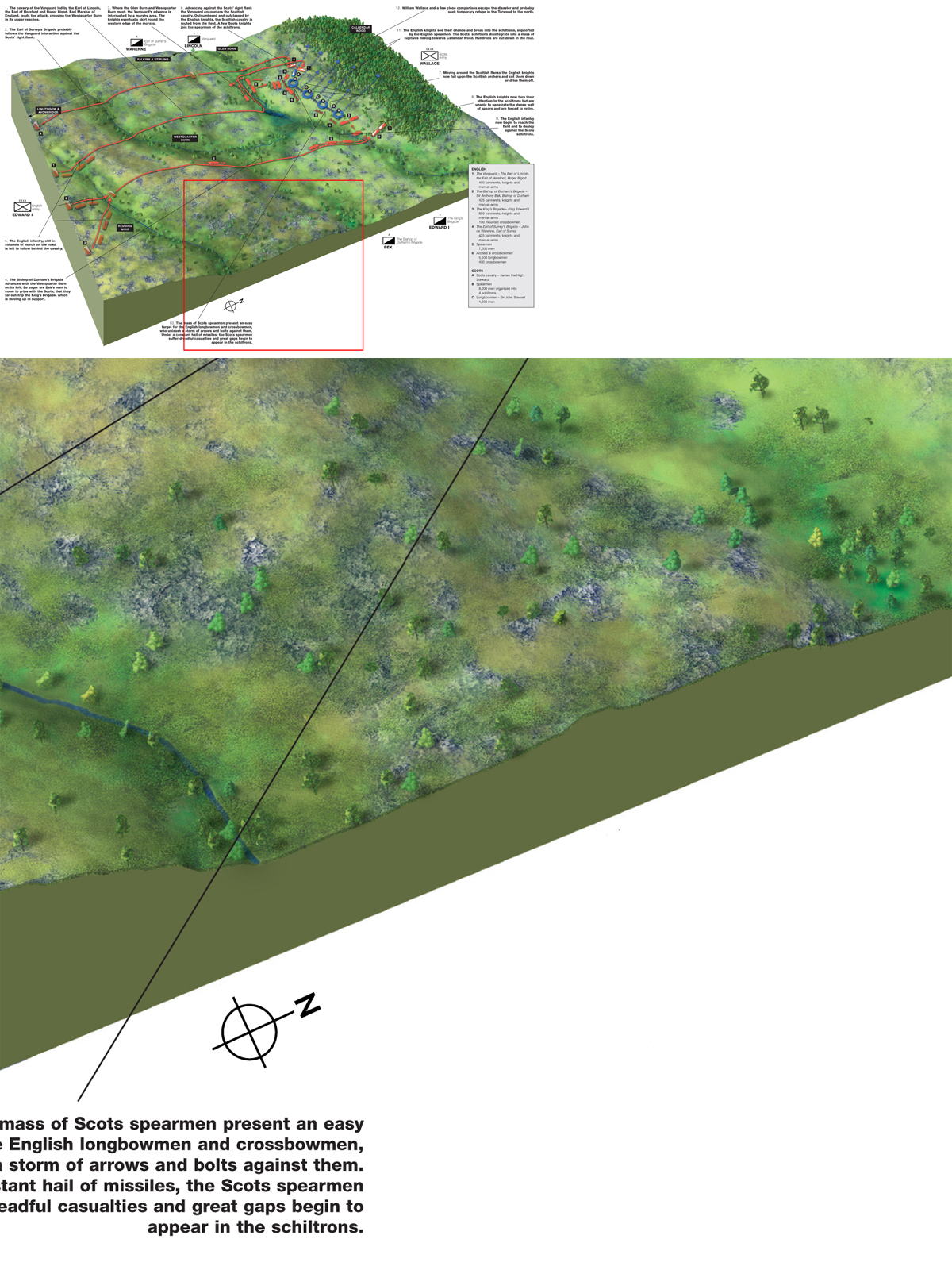

The Scots spearmen were massed into four great circles, ‘which circles are called schiltrouns’, Guisborough tells us. He says nothing of any defensive stakes that may have been planted in front of the spearmen, only that ‘in these circles the spearmen were settled, with their lances raised obliquely; linked each one with his neighbour, and their faces turned towards the circumference of the circle’. I don’t think Guisborough’s reference that the spearmen were ‘linked each one with his neighbour’ implies a physical link. Rather he means to suggest a very solid defensive formation such as that employed by the spearmen of North Wales. It was by means of this ‘human fortress’ that Wallace intended to withstand the English onslaught. Clearly the spearmen were formed up in circles with the expectation of an attack from all sides, implying that the flanks of the Scottish army were not anchored on any physical features but were rather ‘in the air’. In the spaces between the four schiltrons, each made up of about 2,000 spearmen, were arrayed bodies of archers from the forest of Selkirk. They were longbowmen, equal in every way, excepting their numbers, to their opponents; ‘Men of fine build and tall stature’ Guisborough admiringly calls them. ‘And at the back, on the extreme flank, were their knights’; I take this to mean that the cavalry were together in one body, in reserve behind one flank of the schiltrons. It is difficult to envisage the role that Wallace had in mind for his cavalry, they were drawn up in a vulnerable, open position, their presence, as the opening moves of the battle were to prove, invited the attack of the far stronger English cavalry.

View from the bridge over the Union Canal towards the crest of Redding Muir. The cavalry brigades of the earls of Lincoln and Surrey advanced from the ridge, at centre-left, crossed the Westquarter Burn, marked by the trees in the middle-distance and descended the slope in the foreground towards the valley bottom. (author’s photo)

The centre of the Scottish position, on the hillside beyond Callendar Wood, is now occupied by Woodend Farm. The Bishop of Durham’s brigade and that of the king descended the slope in the foreground to cross the Westquarter Burn, the course of which is marked by the trees below. (author’s photo)

The Comyns and other earls who supported Wallace had contributed much of this mounted force and, though they themselves were absent, many of the lesser Scottish gentry were present. These men, despite their poor showing at Falkirk, would oppose the English and provide the core of support for Robert Bruce in the years to come. It has been suggested that Bruce was among these knights but the evidence of his whereabouts at this time is inconclusive. Nor can we be definite about who led the Scottish cavalry but the probability is that it was James, the High Steward.

The Scottish array stood on a dry, sloping hillside facing slightly east of south with the wood of Callendar to their rear and the town of Falkirk some distance away to the north-west, not, it must be admitted as Guisborough tells us, on the Scottish flank. The hillside sloped away towards the shallow valley where the Glen Burn joins the Westquarter Burn; here in the waterlogged valley bottom, in front of the Scottish line, a sodden morass had formed that, after heavy rain, became a boggy lake.

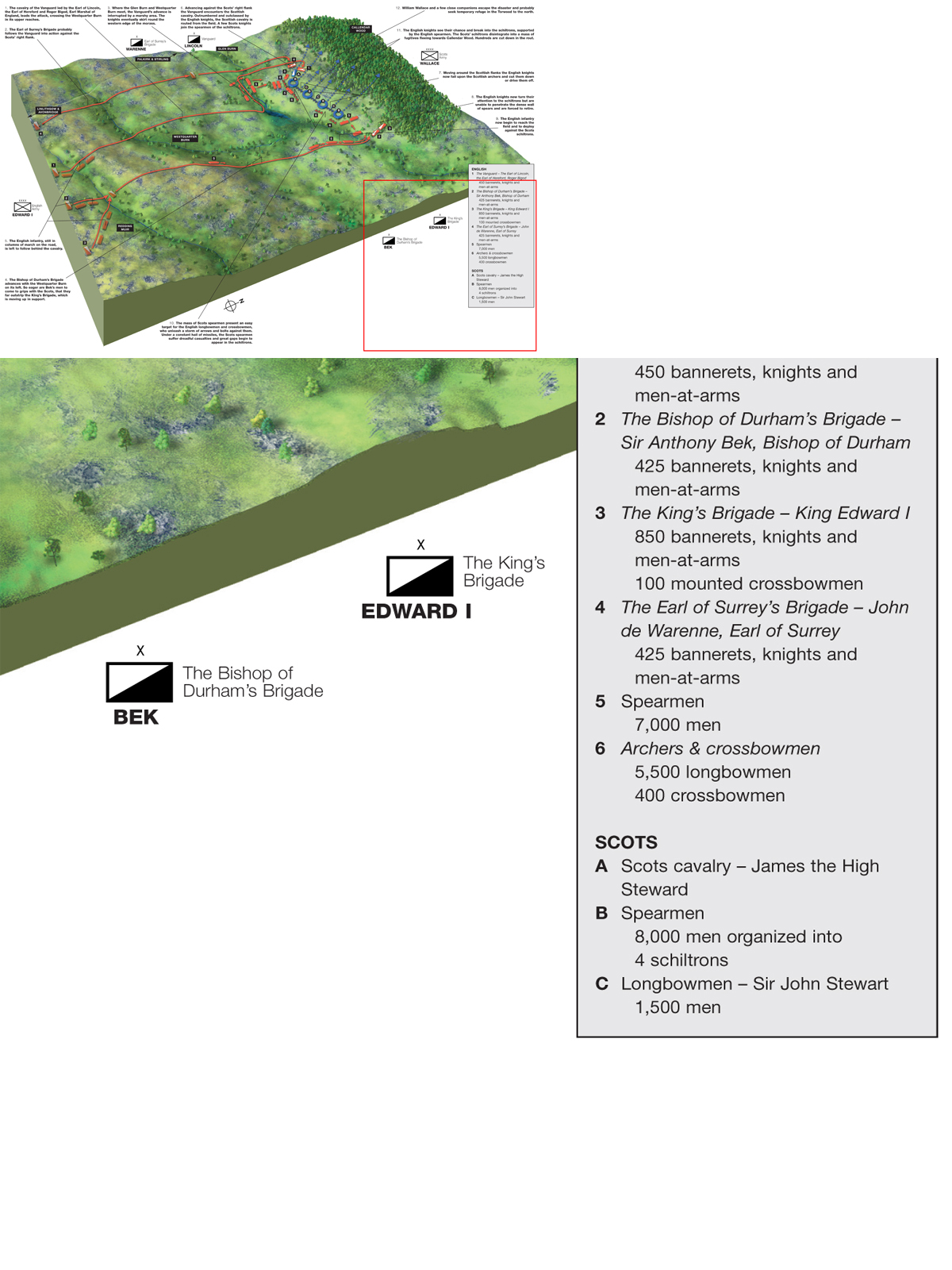

Commander-in-Chief – King Edward I

Commanded by the Earl of Lincoln (3 earls, 18 bannerets)

450 bannerets, knights and troopers

Commanded by Anthony Bek, Bishop of Durham (1 prince bishop, 2 earls, 24 bannerets)

425 bannerets, knights and troopers

Commanded by King Edward I (2 earls, 43 bannerets)

850 bannerets, knights and troopers

100 mounted Crossbowmen

Commanded by John de Warenne, Earl of Surrey (4 earls, 15 bannerets)

425 bannerets, knights and troopers

5,500 longbowmen

7,000 spearmen

400 crossbowmen

Total: 2,250 cavalry, 12,900 Infantry.

Note: The total of cavalry is probably accurate but there is no record of how many of the infantry summoned for the campaign actually took part. Disaffection among the Welsh may have resulted in a high level of desertion in addition to normal wastage.

Commander-in-Chief – Sir William Wallace, Guardian of Scotland.

Commanded by James the High Steward.

500 knights and troopers

8,000 spearmen organised into 4 schiltrons

1,500 longbowmen, commanded by Sir John Stewart

Total: 500 cavalry, 9,500 infantry.

When King Edward saw the situation he hesitated and suggested that, rather than attack immediately, they should pitch their tents and feed the men and their horses as they had eaten nothing since setting off from Kirkliston the previous afternoon. But his commanders and close advisors would have nothing of this delay, saying that it was not safe, ‘for between these two armies there is nothing but a very small stream.’ Presumably they feared that the Scots would attack and catch them unprepared. They urged the king to pre-empt any attack by the enemy and to take the initiative from them by an immediate onslaught of the heavy cavalry. ‘So be it,’ said the king, and he commended the impatient horsemen to the protection of the Holy Trinity. Wallace saw the movements of the horsemen on the distant hillside and knew that this was to be a day of battle and that the decision rested on the courage of his men. He urged his mount across the front of his troops and called out to them his famous rallying cry, ‘I have brought you to the revel, now dance if you can.’

ANTHONY BEK, BISHOP OF DURHAM, AT THE BATTLE OF FALKIRK (pages 70–71)

Anthony Bek, Bishop of Durham (1), commanding the second cavalry brigade, orders his knights to check their advance at the Westquarter Burn and await the king with his horsemen before pressing home their attack on the Scots. Ralph Basset of Drayton (2) arrogantly chides the bishop for what he sees as timidity: ‘Go and celebrate mass if you will, for on this day we will do the fighting.’ After the exchange Bek’s impetuous knights rode on heedless of the bishop towards the dense schiltrons of spearmen on the hillside beyond. Behind Sir Ralph, Edmund Deincourt (3) and Brian FitzAlan of Bedale (4), await the outcome of the confrontation, in their group are the banners of Gilbert de Umfraville, the Northumbrian Earl of Angus (5), an experienced campaigner who fought in the Barons’ War in the 1260s and William Braose, Lord of Gower (6). Beyond the bishop are Piers Corbet (7) and John Peynell, Lord of Otley in Yorkshire (8), who had recently returned with the king from Flanders; both these knights had seen hard service in the Welsh wars. Anthony Bek was a younger son of John Bek of Eresby in Lincolnshire and being well connected, he rose rapidly in the ranks of the clergy and was consecrated Bishop of Durham in 1284. In his time the power of the bishops of Durham as lords palatine reached its zenith. From early manhood he was a counsellor and friend of Edward I and is sometimes called his secretary as he was engaged continuously in his service, accompanying him on crusade and serving as an ambassador in France, Flanders, Wales and Scotland. The Durham historian Graystanes tells how he was seen by his contemporaries: ‘This Anthony was of lofty disposition; second to none in the kingdom in splendour, dress and military power; concerned rather with the business of the kingdom rather than the affairs of his bishopric; a strong support to the king in war and provident in counsel.’ He was constable of the Tower of London and later the Pope made him Patriarch of Jerusalem and Edward made him King of Man. His later years were embittered by feuds with both the king and the Pope. He died in 1311 and was buried in Durham Cathedral, the first bishop to be buried within its walls since St Cuthbert. At Falkirk the bishop's personal following or retinue consisted of 19 knights, five troopers and three clerks. The insubordinate Ralph Basset of Drayton in Staffordshire was a prominent soldier who had served in the Welsh Wars with the Earl of Surrey. He rode a dun warhorse worth 50 marks at Falkirk and brought two knights and nine troopers to the battle, none of whom lost a horse during the fighting, suggesting that neither Sir Ralph nor his men-at-arms made any attempt to charge home against the Scottish spearmen. (Angus McBride)

View from the Scottish position towards Redding Muir. In the valley bottom on the left is the site of the boggy loch. The left wing of the English army advanced down the slopes centre-left. (author’s photo)

The English cavalry was organised into four brigades or ‘battles’, of this we can be sure, but we don’t know whether the infantry was organised independently or whether each ‘battle’ was made up of a combination of horse and foot. Whichever is the case, and I incline to the former, the cavalry initially attacked without infantry support; it would be some time before the foot were up as many were still toiling along the road from Linlithgow. The earls of Lincoln and Hereford and Roger Bigod, the Earl Marshal of England led the cavalry of the vanguard. Their brigade led the attack and approached the Scottish position from the heights of Redding Muir, having crossed the Westquarter Burn in its upper reaches, before their progress was checked by the morass in the valley bottom. This episode caused some delay and confusion while the knights impatiently sorted themselves out before skirting round the bog on its western side, but it had no effect on the course or outcome of the battle. This detour may have brought the vanguard directly into contact with the Scottish cavalry who were posted behind the flank of the schiltrons. Meanwhile, the second brigade of cavalry, commanded by Anthony Bek, Bishop of Durham with the earls of Dunbar and Angus was advancing with the Westquarter Burn on its left. It was alerted to the presence of the morass by the confusion of the vanguard and swerved eastwards to ride round the obstacle. In their eagerness to be first to come to blows with the enemy, Bek’s horsemen far outstripped the supporting cavalry brigade behind, so the bishop himself ordered his knights to draw rein and await the approach of the third brigade, that of the king, rather than attack in a piecemeal manner. The bishop only had about 400 lances in his brigade; the king’s brigade had about 800 men-at-arms, twice as many as any of the other three, and included a strong contingent of mounted Gascon crossbowmen; even combined, the bishop and the king’s commands would have been outnumbered by a single schiltron. But the arrogant and impetuous knight, Ralph Basset of Drayton had no intention of waiting for the king and chided the bishop for his caution. ‘It is not your office, bishop, to instruct us at this juncture in the art of war; you should rather concern yourself with mass. Go’, he said, ‘and celebrate mass if you will, for on this day we will do the fighting’. Ralph Basset’s words epitomise the attitude of the majority of the English knights, notions of subordination and discipline had not yet permeated the ranks of the aristocratic horsemen and though their bravery and spirit were matchless, their ability to act in concert was at best uncertain. Bek’s knights rode on, heedless of the bishop’s attempts to restrain them, spurring their chargers towards the dark masses of spearmen on the slopes beyond. At the same time as the bishop’s brigade came up with the schiltron on the left of the Scottish line, the Earl of Lincoln’s brigade clashed with the cavalry stationed behind their right flank. The Scottish horsemen were outnumbered and outmatched by the English knights and were driven from the field in unseemly rout. So rapidly were they defeated that it seemed, at least in retrospect, that they fled the encounter without striking a blow. A few Scots knights however managed to find shelter inside the hollow schiltrons where they remained to fight and stiffen the defence. Later, there were accusations of treachery on the part of the aristocratic leaders of the Scottish cavalry, much of it aimed at the Comyns, but there is no evidence to support this notion for the Comyns were staunch bulwarks of the patriotic cause and the likelihood is that the charge stemmed from later attempts by Robert Bruce and his supporters to discredit his opponents.

This well-preserved effigy of Brian Fitzalan (d.1306) is in Bedale church in North Yorkshire. He was on military service almost continuously between 1277–1302 against the Welsh and Scots. He fought at Falkirk in the brigade of the Bishop of Durham with six troopers. His arms, recorded by the Falkirk Roll were ‘baree dor et de gulez.’ (author’s photo)

22 July 1298, viewed from the southeast, showing the advance of the English cavalry that, although unable to make any impression on the schiltrons drives off the Scots cavalry and archers. Now isolated, the Scots spearmen are easy prey for the English archers. As their tight formations begin to collapse the English knights and spearmen close in to finish the job.

Piers de Mauley (1249–1308) from the Mauley window in York Minster. He served 1277–1300 against the Welsh, Scots and in Gascony. At Falkirk he fought in the brigade of the Bishop of Durham. (drawn by Pete Armstrong)

Guisborough does not mention the part played by the fourth cavalry brigade which was led by the Earl of Surrey. However, we know that it took part in the fighting because of the record of horses killed belonging to the earl’s knights. One of these was Aymer de Valence whose retinue included the sub-retinue of Thomas and Maurice de Berkeley; they must have been in the thick of the fighting as four of Aymer’s troopers were killed and Maurice de Berkeley lost his valuable horse too. The probability is that the fourth brigade followed the vanguard into action west of the morass. Having put the Scottish cavalry to flight the English knights now turned on the formations of enemy archers. These the English knights caught in the open and destroyed without sustaining any real damage from their fire. It seems that the horsemen, having ridden wide of the morass in the centre of the Scottish line, approached the schiltrons from the flanks rather than the front. With the archers deployed between the schiltrons, their view of the approaching horsemen was masked by the Scottish spearmen until the English knights wheeled round the rear of the schiltrons at the last moment. Lanercost describes the cavalry ‘moving round and outflanking them on both sides’ and Guisborough’s account suggests the confused situation as the archers fought desperately, clustered in defence about the body of their leader, Sir John Stewart, who had been killed when he ‘fell by chance from his horse.’ The Scalacronica gives a different account of this incident and says that he had dismounted ‘to fight on foot among the commons [and] was slain with more than ten thousand commons.’ Having settled with the archers, the English knights then turned on the schiltrons of spearmen but were unable to break through the dense walls of spears. Their horses were vulnerable to the Scottish pikes despite their armour, and the horse lists, which have fortunately survived for Falkirk, show that 111 horses were killed. There is no corresponding record of injuries to the riders, but casualties do not seem to have been heavy, we know of only two bannerets who were killed in the battle. In the king’s brigade Henry de Beaumont lost his own horse and three more from his retinue of ten, Robert Clifford lost eight out of 35 and the Earl of Lancaster 11 out of his large retinue of 45. Ralph Basset of Drayton’s retinue of 12 knights and troopers, despite his insolent bravado, suffered no losses. He, like most of the cavalry, probably circled round the schiltrons probing for a weak spot. Horses will not, no matter how they are spurred on, charge home onto the points of spears. Being intelligent, sensitive animals rather than machines, they will invariably swerve away rather than commit suicide. A shower of bolts shot by the mounted crossbowmen galled the immobile Scots but their surviving bowmen, who had taken refuge within the schiltrons, returned a brisk fire that helped keep the horsemen at bay. The English cavalry were far outnumbered by the spearmen and, without the support of their infantry, they could not defeat them. Nor for that matter could the Scots, stripped of their cavalry and most of their archers, do much damage to the English cavalry. For the present there was an impasse. The English cavalry was not beaten, far from it, their casualties had been light and they had successfully put the Scottish cavalry to flight and destroyed their force of archers. The schiltrons were left isolated and apparently immobile, awaiting what seems, at least in retrospect, the inevitable.

John de Segrave (d.1325) fought at Falkirk in the vanguard with the Earl Marshal’s retinue. He escorted the prisoner William Wallace to London in 1305 and was chief justiciar for his trial. (model by Pete Armstrong)

Aymer de Valence (d.1324) from his tomb in Westminster Abbey. He fought in the brigade of the Earl of Surrey at Falkirk where four of his retinue were killed. (author’s drawing)

The stand-off gave the Scots a short breathing space before the onslaught of the English infantry. They had advanced in the wake of the horsemen, who drew back to re-form their ranks. The massed schiltrons of spearmen presented an easy target for Edward’s archers who unleashed a storm of arrows and crossbow-bolts that decimated the forward ranks of the Scots. In addition to the archers, Guisborough tells us that ‘some brought up round stones, of which there was a great plenty there, and stoned them.’ We can’t be sure that these men were dedicated slingers or simply infantrymen who took the initiative to pick up stones and add to the hail of missiles that was taking its deadly toll of the Scots. Gradually the schiltrons, unable to reply to the barrage, began to waver and contract as men fell and the outer ranks were forced backwards on those behind. ‘They fell like blossoms in an orchard when the fruit has ripened’ wrote one English chronicler. As the deadly rain did its work, gaping holes appeared in the schiltrons and the English knights saw their chance and broke in among them, hewing down the spearmen at close quarters. Though Guisborough makes no further mention of the English infantry, the cavalry alone cannot have completed the defeat of the Scots, who would still have outnumbered them. The English foot, even allowing for the usual wastage, must have been at least as strong as the Scots infantry and would have included spearmen, in large numbers, who would have had some part to play in the final stages of the battle. A shred of evidence for the involvement of the infantry is provided by the horse lists, which record that the horses of John de Merk and William Felton, both millinars of infantry formations, were killed in the fighting. As the full weight of the English army was brought to bear against the Scots formations, they began to break up and men streamed away towards the rear; hundreds were cut down as they fled towards Callendar Wood. The only recorded English casualties of note were Brian de Jay, Master of the Templars and brother John de Sawtrey, Master of the Scottish Templars. One version of their demise has it that their horses became bogged down while incautiously pressing the pursuit and they were surrounded and killed in the woods; however, Lanercost says that the Master of the Templars was killed when he ‘charged the schiltron of the Scots too hotly and rashly.’ William Wallace, with a few of his closest companions, escaped the disaster and fled to ‘castles and woods’, probably finding a temporary refuge in the Torwood, five miles to the north of Falkirk. When the English reached Stirling on 26 July they found barely a building habitable save the house of the Dominican friars where the king made his headquarters; Wallace had destroyed much of the town as he retreated north from the Torwood.

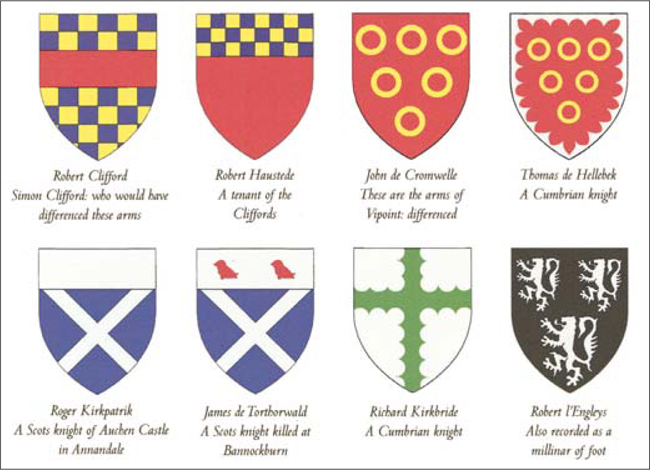

Knights of Robert Clifford’s retinue in 1298. (Illustration by Lyn Armstrong)

Seal of Eustace de Hacche (d.1306) who, with the two knights and nine troopers of his retinue, fought in the king’s brigade at Falkirk where his charger, a bay with a white hind foot was killed. (author’s drawing)

Ralph Fitzwilliam fought in the Bishop of Durham’s brigade at Falkirk. His effigy at Hurworth-on-Tees displays his arms, ‘barry argent and azure three chaplets gules’. (author’s photo)

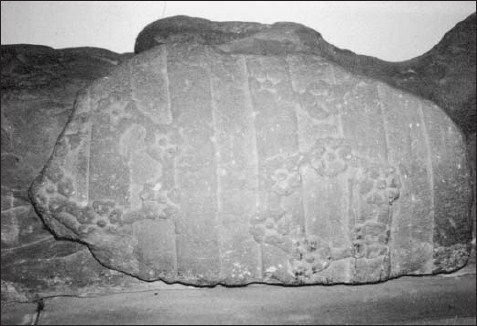

Contemporary chroniclers record huge losses among the Scots; the Scalacronica’s estimate of ‘more than 10,000’ killed is an exaggeration but within reason. Guisborough’s 56,000 and Walsingham’s 60,000 dead are preposterous and far exceed the number of Scots on the field though they may reflect the scale of the disaster and the high proportion of casualties, most of which were suffered by the common folk. For once a few of the names of the commons are recorded; they can be found in the archives at Durham. They are freeholders of Coldingham, in Berwickshire, who were either killed, wounded or forfeited their land for their part in the ‘discomfiture’ of Falkirk. Edward I ordered a series of forfeitures to take effect from 22 July, the date of the battle, clearly indicating participation in the affair. These indicate the presence at Falkirk of a section of the Scottish gentry, though only the High Steward among the great lords seems to have been present in person. The names of some Scots knights who fell at Falkirk are recorded; Andrew Murray of Bothwell and Macduff of Fife, James Graham of Abercorne, and Sir John Graham, whose tomb is in Falkirk churchyard along with a stone that marks the grave of Sir John Stewart, the Steward’s brother, the manner of whose death is described above. Only the Templars, among those whose names were deemed worthy of recording on the English side, were killed. Losses among the English foot are not recorded but there is no reason to suppose that they were heavy.