Is it enough to be able to label our symptoms? We don’t think so. We don’t think so because we know that it isn’t enough just to have this information. Our clients don’t get better with just information. Denial systems don’t change with just information. Feelings don’t get out with just information. What we also need to understand is the process by which these symptoms were acquired. They didn’t happen overnight. We don’t just wake up one day and find that we are now living a painful life. It is a process that takes a long, long time to happen.

Bill’s Story

Bill Hopkins entered treatment for sexual addiction1 at the age of 38, after an intervention that was attended by his wife, his two partners in the accounting firm that he founded, his sister and a friend of his.

Two years prior to the intervention, Bill’s wife became concerned about his sexual acting out. She started to make regular comments to him soon after that. As is often the case, Bill dismissed her concerns with a wave of his hand at first, saying, “Dear, if I really had a problem, I’d do something about it. Really, honey, worry about something else for awhile.” Anita kept worrying, though.

Several months later the situation escalated to the next stage. Bill’s involvement with pornography and masturbation increased as the pressures from expansion of his business increased. He took on a junior partner, but it didn’t help his addiction. Bill grew distant from Anita, and their interactions became either cool and perfunctory, or heated battles and debates. The friction in their marriage became more and more intense, until one Friday night when the trap snapped completely around them.

Anita had been out with a friend for dinner, which she had begun to do more and more out of frustration and helplessness. When she walked through the door at 9:30 that evening, Bill told her that he had contracted a venereal disease and that he couldn’t have sex with her for awhile. Anita packed a suitcase, went back to her friend’s house, and spent the weekend with her. On Monday morning she filed for a separation. The next day, Bill called her, apologized, and said if she would move back home, he would stop acting out immediately.

Anita moved back into their house and things cooled off for several months. Bill was actually proud that they had been able to work this out by themselves, and Anita was tremendously relieved that she wouldn’t have to be watching Bill all the time. Their communication was still a little shaky, but it was improving. About three months before he entered treatment, Bill decided that he had the whole thing under control and that his sexual addiction had only been a symptom of the business pressures that he now seemed to have managed well.

It wasn’t long before his addiction had escalated again to destructive proportions. Anita contacted COSA (Co-dependents of Sex-Addicts) and asked for some help. They put her in touch with an intervention specialist who met with her and the other concerned persons who would do the intervention. One week before the intervention was done, they all sat down and practiced how it would be accomplished. When Bill was faced with his wife and friends and the data they presented him, he grudgingly accepted their recommendation for treatment, which was the beginning of his and Anita’s recovery process.

Admitting a problem like sexual addiction carries with it both a sense of relief and a sense of failure and loss, and one of the goals of treatment for addictions is to educate the family about how the addiction process is acquired. Everyone is asking themselves, “How could this happen to us? Who caused this? Who is to blame?”

One of the goals of this educational process is to let people see the dysfunctional dynamics in their present families, and to see how those dynamics developed and were passed on through past generations. The goal is not to blame. At first, it is almost impossible for us not to blame someone for this mess that we’re in. Only later can we detach from our parents and grandparents enough to say, “What went on with them was not healthy. I can choose to live another way even if they don’t so choose.”

As Bill and Anita explored their family backgrounds with their therapists and in their support groups, the following generational picture emerged.

There were no obvious addictions in Bill’s parents’ marriage. Mom and Dad Hopkins were teetotalers, in fact, who had no addictions to any chemical substances at all. And at first, Bill described his childhood and his relationships with his parents as “just normal”. But as his process of self-discovery continued, bits and pieces started to fall into place. Bill’s dad was a hard-working “bring-home-the- bacon” kind of guy who ran his own auto mechanic shop in the small town where they lived. He spent a lot of time teaching Bill how to fix cars, and he seemed to be actively involved in raising Bill. But he was also an extreme perfectionist. Their garage was always spotless. Their house was always quiet. Everything was always under complete control, and there was never a question about Dad wearing the pants in the family. He had quite a temper, too. He never carried a grudge, but he was painfully critical whenever Bill would make a mistake, make a mess in the garage when working on cars, or somehow not live up to his expectations for Bill.

Thus Bill grew up with a highly overdeveloped inner critic that was always telling him that if he didn’t do it perfectly, then it wasn’t worth doing at all.

Bill described his mother as “a saint.” She was shy, retiring and very hardworking. She kept a spotless home and raised five children, of whom Bill was the oldest. She also received strong messages about perfection from her husband, and was emotionally distant from the children. Bill never remembers his parents hugging or kissing in front of the children, and in fact, doesn’t remember anyone in the family being comfortable with appropriate touching.

Despite the perfectionism and domination of the family by his dad, Bill at first did not see the connection between that and his own problems. In going back another generation, the pieces started to fit more, though. His grandfather on his father’s side was never diagnosed alcoholic, but it was a well-kept family secret that he had a pretty serious drinking problem.

Grandpa Hopkins led two lives. Outside of the home, he was generous, charming, humorous and well-liked by the community. Inside the home he was a tyrant who screamed and yelled when his wife asked for grocery money or extra money for school clothes for the children. He drank a lot at home, too, it turned out.

Grandma Hopkins was a quiet, compliant woman who tried to keep the peace by going along with whatever her husband demanded. They, too, showed no outward affection with each other.

On his mother’s side, his grandparents’ roles were just the opposite. His Grandpa Smith was a quiet, shy man, who always felt pretty worthless, who never really “made anything of himself,” and who did what his wife told him to do.

Grandma Smith was domineering and controlling, and angry and bitter about her husband’s perceived failure in life. She had a quick temper and was perfectionistic to an extreme. As the oldest child, Bill’s mother identified strongly with her father and was kept in her place by her angry mother, and thus grew up not knowing how to be warm and nurturing.

As we so often do when dependencies are left untreated, Bill’s mother married a man who had many of the negative traits of her mother believing that his strength and sense of goal-directedness would fill in her own lack of these. And what she first saw as strength, eventually emerged as all-out domination. The fact that he had “made something of himself” far overshadowed the fact that he had some clear problems in being intimate and supportive in a marriage.

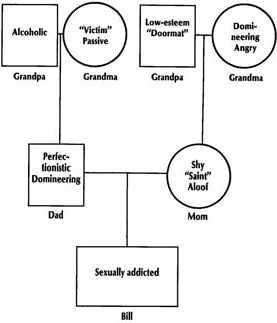

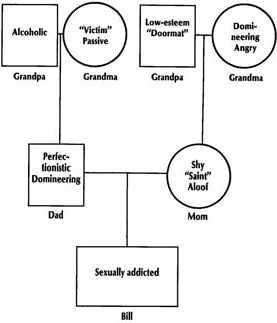

And so the pieces began to fall into place for Bill. Patterns began to emerge that made sense. To avoid the confusion that you may have about this family so far, we have outlined Bill’s family tree, in terms of the important personality dynamics, in Figure 7.1, using the diagram that Bill eventually put together for his own understanding.

The other piece of the puzzle that is missing, of course, is how Anita became entwined in this system. As is almost always the case, the spouse of the person who goes in for treatment or counseling rarely sees their own contribution to the problem because they have become so overly focused on their partner’s problems that they can’t see anything else. It is also common that their focus on their partner is an unconscious way to avoid looking at their own untreated dependencies. Remember paradoxical dependency?

At first Anita told herself, “Why, there’s nothing for me to work on. When Bill finally stops acting out, all of our problems will vanish. I’m responsible. I’m the strong one in this marriage. Without me everything would have fallen apart long ago!”

Figure 7.1. Bill’s Family

Fortunately for Anita and Bill, the treatment program Bill entered was aware of family dynamics and co-dependency, and they knew that it takes two to tango. Anita began to discover things about herself and her family that she had never examined before, and she found it to be just as painful and scary as Bill’s discoveries about himself.

She knew all along that her mother had a tendency to rely on alcohol under stress, but she had never let it cross her mind that maybe her mother was alcoholic. Her mother had never passed out, had never gotten “sloppy drunk” in front of her, and had never seemed to have a problem.

And Anita had always seen her father as the ultimate “Dad.” He was hardworking, responsible, cooked dinner when Anita’s mom wasn’t feeling well, played with the children on weekends, went to school plays and concerts, and was always easygoing and pleasant. What Anita didn’t know was that Dad was very tired inside, and mildly depressed much of the time, really not the happy-go-lucky guy that he tried to be on the outside.

And it never bothered her that no one seemed to know anything about her grandparents on either side of her parents’ marriage. All anyone seemed to know was that they were European, and that both of Anita’s parents had come to America in their early teens, accompanied by aunts and uncles, or something.

As the oldest child in her family, Anita identified very strongly with her father and took on the role of the “good girl.” When Mom was tired or “ill,” Anita would help Dad do the cleaning and cooking. She would babysit the other children gladly, even when she was a teenager and could have been out with her friends, learning how to date and socialize. It didn’t bother her when Mom was cranky and irritable, because like Dad, “she understood.” Mom wasn’t feeling well.

So from a very early age, Anita became a little parent, giving up her own childhood to take care of domestic chores, do well in school and stand beside Dad as one of the “adults” in the family. This became her set-up and her steel trap. With the trap securely set over years and years of growing up in her family, Anita was ready to go out into the world and get into her own dysfunctional relationship.

1For an excellent discussion of sexual addiction, see Patrick Carnes’ Out of the Shadows and Ken Adams’ article entitled “Sexual Addiction and Covert Incest” in Focus On Chemically Dependent Families, May/June, 1987.