Early Life

Neither of my parents was born in the United States. They both emigrated from Hungary. My father was born March 7, 1894, and Mom was born two years later. Pop could, more or less, speak seven different languages, so for one of his professions, he eventually became an interpreter for Municipal Judge Hunsicker1 in Akron whenever the accused could not speak English. Even though Pop spent many working days in a courthouse, he was mostly an outdoorsman, and my brothers and I picked up this trait. It was one that would shape a good part of my character.

I was the third of four children. The oldest was Elizabeth Rose, born six years before me on August 25, 1916. She was a somewhat thin brunette with a high forehead. I remember her as being sort of prissy, typical for a female in those days. Next in line was my older brother Alex, born July 25, 1920, in Trenton, New Jersey. A year after Alex was born, our family moved to Akron, Ohio. The next year, on September 18, 1922, I came into the world, born at home, with my mom assisted by a midwife. Soon after, our family settled on a backwoods farm in the Portage Lakes area south of Akron, and on June 2, 1928, when we lived in nearby Barberton, Ohio, younger brother Steve was born, mom assisted again by a midwife. That’s all poor folks like us could afford in those days.

My old man had a wild streak in him that in his youth often got him into trouble. Having a motorcycle sure as hell did not help. Nor did being an alcoholic. Yeah, as he grew older, he drank like a fish and smoked like a fiend. (Luckily, smoking was a bad habit that thankfully none of his sons ever took up, although unfortunately, Liz did.) In fact, Pop did so many things in his life the wrong way. Yet somehow, the old man lived to be 92 years old. Pop was a great contractor, quite the entrepreneurial self-employed builder. I mean, of just about anything. I remember in my youth that my brother and I would often go out with him and assist him in building a house, or a garage, or a fireplace or something. Sometimes, we dug basements for folks. Whatever we could do to make a buck, we would do.

Earlier in his life, my old man had trained to be a cobbler. In later years, on the east side of Akron, he started his own shoe repair store, selling and repairing shoes. Unfortunately, Dad gave up the trade, because he was not making much money at it. Also, in his mind, even an expert cobbler was a still lowly profession, not worthy of his own talents. So he decided to give up the store and become a freelance contractor. Mom couldn’t talk him out of his decision. In fact, she pretty much could not talk him out of anything. You just could not reason with him, especially when he was drunk. Anyway, Pop pretty much did as he damn well pleased.

And he could be one mean old bastard. Once when I was in grade school, I played hooky a couple times. I was hanging around the swamps with a friend of mine, Bob Rining, who lived down the street. Finally, my teacher, frustrated with me (as she often was), gave my sister Elizabeth a note to take home to my parents. Liz brought the note home and gave it to Pop, and he got mad as hell.

Determined to catch me in the act, he didn’t say a word to me when I came home that afternoon, and nothing happened to me that night. So the next day, unsuspecting, I skipped school again, and went down to the canal with Bob to take my beat-up canoe out for a ride. After a while, my father came down along the shore, spotted us, and stood on the bank, watching us idly paddling away, happy as a couple of larks. He did not even yell out my name: he just stood there, silent.

Finally, I looked up and saw him there glaring, and my heart skipped a beat. With a mean look in his eye, he wiggled his index finger, motioning me to come ashore. Taking a deep breath, we paddled over to the bank and got out of the canoe. Man oh man, that’s when all hell broke loose. He beat the crap out of me going up the bank and all the way back to our house, some three blocks away. That did the trick. No more skipping classes. I never missed a day of school after that. I was never easy to convince to do things, and normally, I often did things with little thought of the consequences if they were not hurtful or fatal to anyone. But this lesson took. Boy, did it take.

During these years, Alex and I often fished with dad at Wingfoot Lake. One thing that I vividly remember around five years old was seeing all these balloons floating around in the sky. They called them “airships,” but to me, they were big balloons. Most of them were those shorter blimps, although early on, we once in a while saw one of the huge, long dirigibles, like the German zeppelins. Before World War II started though, they stopped making those and were just making blimps. But because we lived so close to the Goodyear factory, we could clearly see the Akron blimp building from the lake. In the summer, you could see them flying around, and I swear, Goodyear must have had a blimp named for every month of the year. I’d just sit there in the boat or along the shore and stare at them. Once in a while, we’d see one of those big long dirigibles, like the Akron or the Macon. They’d glide on by, or sometimes hover near the ground as the ground crews worked to land them.

Life on our farm was primitive. We lived in a heavily forested area, with lakes, rivers, and swamps all around us. We were not far from the Ohio Canal, and we always kept a boat there that we used to go fishing or just exploring. We grew over half of our own food, and life as such was basic. For one thing, we had no indoor bathroom, and so going to the head in the wintertime was sometimes rather uncomfortable.

Country life like that was sometimes a challenge. For one thing we had bedbug problems. Not that this was unusual, because back then everybody in our area had bedbugs. My father though, was rather effective in controlling them. He just used a torch. It seemed to be an effective technique, and anyway, as poor as we were, we really had no alternatives. Chemicals for that sort of thing were not easily available back then; the only thing that you could buy came in powder form. That stuff was expensive, and anyway, it was not very effective against them.

Pop’s treatment was unique. Every month or so, he’d take our beds apart, and we would drag them outside. He would then separate the mattresses from the frames. The mattresses were filled with straw, so the remedy was easy. We would remove the old straw and burn it, while mom boiled the mattress covers. We owned a couple of blow torches, which were common back then. Each one was about 12 inches high, with a six-inch-round fuel tank. In it we would put gasoline or kerosene. Then he would pump up the blow torch, turn on the fuel valve, and light it. With a flame about a foot long, he’d take the torch and go to one corner of the bed frame, where it connected to the springs underneath. He would then go down the line of the bed springs and cook them little critters. And you could hear them sizzle and pop as he did. When he was done, he would then take the bed back inside, and we would be good for another month.

Because we lived as primitively as we did, we had to spend a good deal of time outdoors. Pop often took me and my two brothers out hunting for food. Rabbit was a common course for our meals. I had my own first kill when I was nine years old, and after that, I was never too content indoors. I inevitably became an avid outdoorsman, and so I never really acclimated to indoor activities. School, an indoor activity, was always difficult for me, because I preferred to go roaming through the woods looking for adventure, longing to just go exploring. Often, as a young teenager, I would get a friend to go with me and just take off to see what we could see. I took along any sort of basic road map and kept it in my back pocket. We walked wherever our curiosity took us, sometimes hitchhiking across the state by truck or by train. We sometimes stopped for the night on a hayloft or in a barn, before starting off for home the next day. It was a blast for me, and my curiosity always seemed to lead me to something new.

This outdoor nature of course had its drawbacks. As a teenager, it made my holding any job difficult. That was a big problem, because back then in the early thirties, jobs were difficult to land. However, I was an excellent hunter, and many was the time I would happily go out hunting with my dad for hours on end.

As I grew up, partly because of how we lived, I developed a positive attitude on life, and more often than not, I would not take things as seriously as sometimes the circumstances would dictate. I usually preferred the grin or the chuckle over the frown and the growl, and most of my teenage friends considered me to be more or less a happy-go-lucky fellow. So if someone got serious on me, I would laugh. Over the years, I found that this sort of lighthearted attitude was a double-edged sword. Sometimes it worked in my favor; certainly with the girls. Sometimes though, it backfired and worked against me; mostly with authority.

I remember one time when I was in the second grade. My teacher was this beautiful lady. I thought she was prettier than any gal I had ever seen, and I have to admit, I was smitten by her. We were studying a classic poem, A Tree, by Joyce Kilmer, and in the middle of it, somebody made a smart remark. Our teacher looked up from her book and sternly asked, “Who said that?”

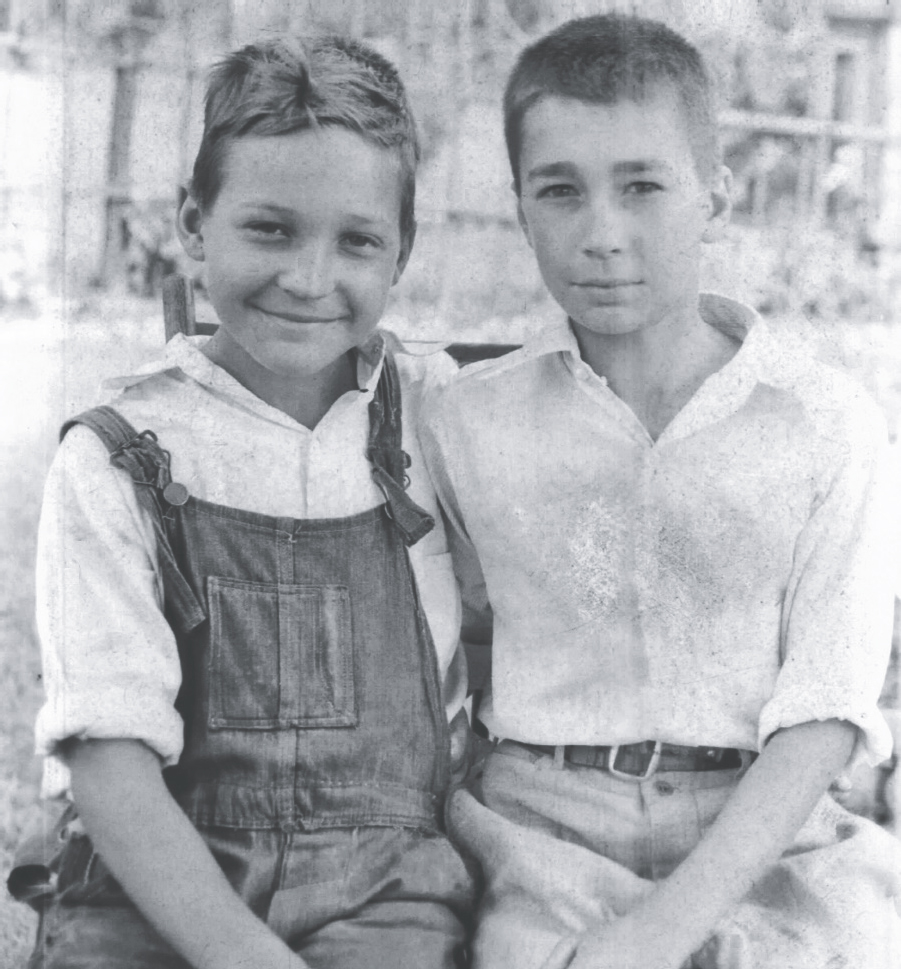

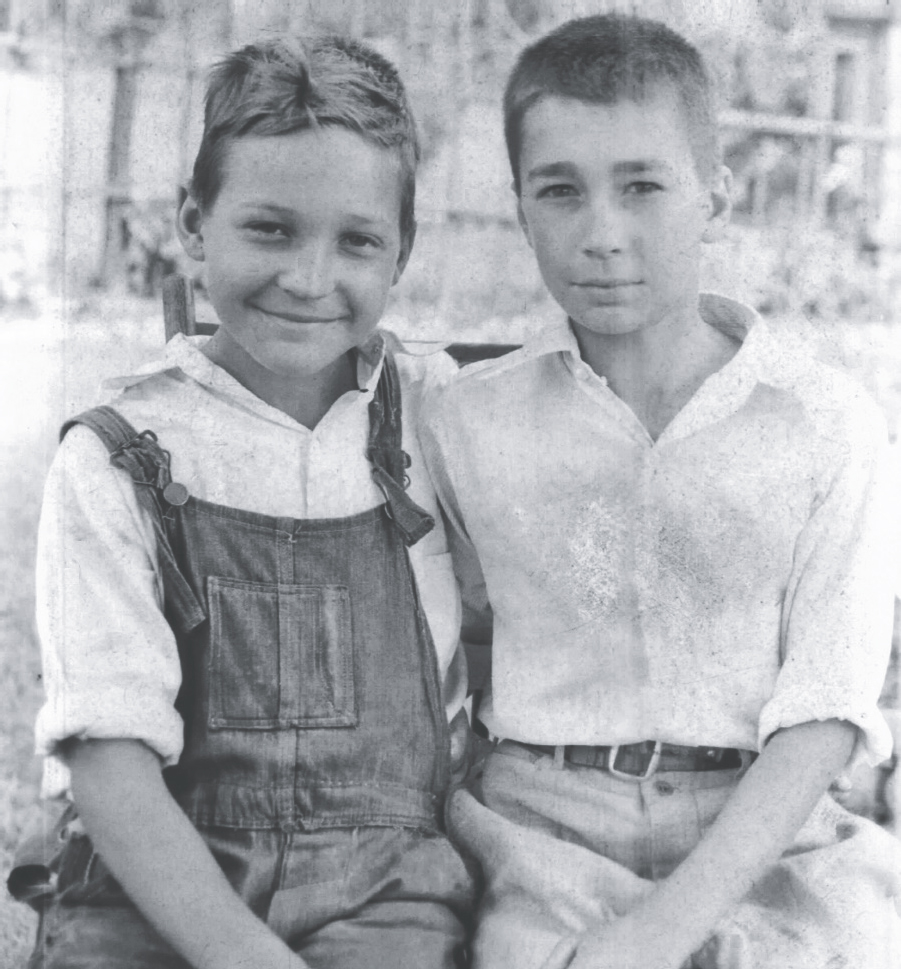

George (left) and Alex Peto as children, taken in around 1931. (Author’s collection)

The room was dead silent. She glanced around with a scowl, and started walking down the aisle, looking at everybody. She came to where I was sitting and looked at me. I was smiling.

She calmly concluded, “You’re the culprit.”

“No, ma’am. I’m innocent.”

But she didn’t believe me. We went on reading the poem. A little later, one of the boys in the back took a small wad of paper and threw it across the room, lightly hitting her in the back. She whirled around, now angry. The guilty party was openly defying her. “Who threw that paper?” she snarled.

Again, none of us said anything. She started walking up and down the rows of desks again, glaring. When she came to me, I just looked up and grinned at her. It had just struck me as being funny, and now I was trying to hide the grin by looking innocent. It backfired. She smacked me hard on the head. I saw stars.

By 1928, we had sold our first home and had twice moved away from the development sections. Now, we had moved into an area below Akron that was called the Portage Lakes, which included some eight lakes in the area. Living there, we were right next to the Erie–Ohio Canal. There were several reservoirs in the area that helped supply the canal, so water was always nearby.

In one remote area, there was a small dirt lane that went far back and eventually ended in an open area next to a swamp. The older kids used it as a lover’s lane. The main road that goes south in that area, State Route 93, is called Manchester Road.2

We lived on a simple, beat-up farm near Nesmuth Lake3 (we called it “Mud Lake”) on the north side of Carnegie Avenue, the only crossroads in the area. Back then, the area was open country, with swamps all over the place. There was no civic development, and there were no paved highways; just dirt roads with pylon street markers, and some pretty maple trees alongside our road. We got some livestock that we took care of: a horse, some pigs, and even a cow. Our house was next to a swamp, and there was a drainage ditch nearby. Dad and I built a small shelter over it for some ducks I had caught.

It was around that time when I became aware of the fact that the old man had become a bootlegger. I remember the time, because I was supposed to have started school that year, but I did not.

From the time I was born until the time I joined the Marines, we lived on several different farms in south Akron, all in a five-mile radius. We did not stay too long in any location, and we had to move a good deal, and that was for one good reason: the rent would come due. My old man unfortunately seldom paid his bills, and paying the rent was an on and off thing for him. He would run up a debt, and then either could not pay or would not pay; so as a result, we sooner or later were forced to move.

I grew up making a number of friends. Probably the closest were the Getz brothers. There were three of them, just like there were three of us Peto brothers. Our two trios hung out a lot, often sitting at each other’s family dinner tables. We shared most everything, and promised that we would always stay in touch.

My close buddy was the middle brother, Melvin Forest Getz—we called him “Waddy.” The older one was named after their father, Seymour, so we called him “Danny.” The youngest was Warren; we called him “Boysee.”

Waddy was a little over a year older than I was, and the two of us got along great. As we grew to be teenagers, he developed a strong, muscular physique, one that he often bragged about. He had a right to, because he really was a tough son of a gun, a pretty rugged guy. As he grew older and bolder, he once in a while would go into a bar and start a fight by picking on the biggest guy. Once in a while he would lose and come out bloody and worse for the wear, but he always came out laughing.

I guess that I was in my share of brawls too. There was this one guy that I went to school with named Paul Dunlap. One day, he started bugging me, ordering me around. I kind of let it go, but the second day he pushed me around, I started getting mad, realizing what was going on. He was just out and out bullying me. The third day he started in on me, I’d had enough, so I let him have it. We started fighting, and after about five minutes of trading punches, to my surprise, he started laughing. Me, I was fighting dead serious, but I guess he wasn’t. We finally stopped, and we made up. We ended up being friends after that. Not good ones, and I never got to where I trusted him, but we respected each other.

Yeah, even as kids, we did a lot of fighting back then, partly because it was rough where we lived, and partly because that was one of the few forms of entertainment that we had. And boxing was not only condoned, it was often encouraged. There used to be carnivals or sporting events where boxing matches were set up, and you could enter for next to nothing to compete for prizes, which sometimes were sponsored by our schools.

We used to box a lot back then. Mostly it was for fun and to pass the time, sometimes just to get better at doing it. Remember, boxing was really popular back then, and tickets for a good boxing match would go for good money, just like folks today would pay a lot to see a good basketball game. So we would box at all these different places. There was one place in town that had a bar on the first floor, and upstairs they had a gym. So we would go there and box.

We would box at other places too. A number of grade schools and high schools had a Weona Club,4 and every Wednesday night, the school would have a dance, or a set of boxing matches. Often, we would go and just box. Hell, all you just needed was a pair of gloves and a ring. Or, we played basketball. All you needed was some sort of hoop and a ball that bounced. What equipment we didn’t have, we improvised. Just like hockey, for instance. For hockey sticks, we’d go down to the canal and find these big bushes growing along the banks. We would each find a thick branch that curved up and went out over the water, and we would cut it off. We would then take these wooden branches, dry them out, and then shape them with our knives into hockey sticks. And for a puck, we’d get an old tin can, put a stone in it, crimp the ends, and then beat it around. That was it.

In the spring and summer we played baseball. Again, just the basics. All you needed was an open field, something that passed for a glove, a bat or a stick, and something that could pass for a baseball or softball. There was this one big field near my house, and there was a path that went right through it. Just about every time I went by there were a few kids playing on one side or the other. There were never any adults or supervisors; just us kids.

We did other things to pass the time. Being around the Portage Lakes and the Ohio Canal, we swam a lot. There was one remote spot that we called the “B.A.B.,” short for “Bare-assed Beach.” It was along the old Ohio Canal, a half mile down and back through the swamps. Most of the time, the swamps kept cars from going down there, so we were safe. On warm days when we had spare time, we would walk over there, yank off our bib overalls, drop them on the bank of the canal, and hit the water.

The cops knew what we were doing, but couldn’t get down there to catch us and run us out. Except sometimes, when the weather had been hot and dry for a while and a car could get down there. So the cops would every now and then sneak down whenever they didn’t have to worry about getting stuck and try to catch us. Usually though, we would see or hear them coming, and hide. There were these heavy bushes growing along the bank, and so when the cops came looking for us, we’d hide under the bushes.

One time they got wise to us and looking around, found our clothes. They grabbed them and then told us to come out, or else they’d take them. After thinking about it a bit, and after they warned us that we would get in more trouble and that they were leaving, we finally sheepishly came up out of the water. They then gave us hell, but they didn’t take us in. They understood that that was our recreation.

There was a lot of stuff that we did as kids, and because we were so poor, we had to do some innovative hillbilly engineering. Luckily, we had a lot of material to work with, even if it was all junk. Sometimes, we’d go to the junk yard for things we needed, or find a junk haul someone had dumped. We often salvaged nails out of the boards. You see, back in those days, there were no sophisticated waste management services, especially out in the boonies where I lived, and especially not during the Depression. Often, folks just took their sacks of garbage out to the dumps and just pitched it, along with a lot of other junk that they didn’t want. So we would get a lot of what we needed to fashion our own stuff.

For instance, we used to get a bunch of old bottles and play mumbly peg. Waddy and I often played, but sometimes Waddy’s younger brother Warren, about my age, would play with us too. Warren, like his older brother, had a short trigger too, and would start a fight at the drop of a hat. That’s the kind of guy he was.

Being out in the country, we also fished and hunted a lot. A lot of it was for our own consumption, but often we hunted to earn some extra money. In the early thirties, when I was around ten years old, my brother Alex and I for a while ran a muskrat line and trapped muskrats along this big, cattail pond. Since we could not afford to buy a trap, we did the next best thing: we stole one.

One day when I was down along the canal, I saw an empty muskrat line. Taking out my knife, I cut the line, lifted the trap out of the water, and took it home. Just like for ocean fishing, traps had to somehow be identified, and this one had the owner’s name etched into the metal. So, with a file, I sanded off his name. Then I carved my own initials onto the metal, and voila! our own trap. Alex stole another one, and now we were ready for business.5

We mostly tried to trap the muskrats for the fur. If we caught any, we would skin them with a couple of wooden roof shingles that we carved out to look like arrowheads. Then we turned the muskrat inside out, sliced all the meat off real good, and then turned it back the way it was. They we rubbed it with salt to cure it.

We would then take the furs, dry them, and when we had three or four, we would sell them. The meat we would take down to Snydertown6 and sell them for 25 cents apiece—which was a good deal for us, because those poor people there just loved muskrat meat. Then we would take the furs to some guy that bought furs for a living, and get $1.65 each. Of course, that was for a prime fur, with no holes or nicks in it. Otherwise, the buyer paid us less.

One nice thing about this was that Pop actually supported our operations. In 1932, he built us this little shed with a small roof that had two sloped sides. At the top of the shed we built a loft where we took care of some tumbler pigeons.7 I drilled a couple holes into the side near the top, and the pigeons would come in and live inside at the top. Behind it, Alex and I had a chicken coop where we kept dozens of chickens. There was a small stream back there, and we built a chicken coop right along the stream. Over the next six years, I also caught and eventually tamed some 15 or 20 mallard ducks and kept them there. To keep them from flying away, I would trim their wings on one side with a pair of scissors, so when they tried to fly, they’d get airborne and flip around and fall to the ground.

Despite the fact that in 1934 that the country was in the Great Depression, I surprisingly had a lot of fun just living life. We were just outside of Akron then, living in an underdeveloped part of Kenmore.

When I was 12, we fished a lot at the lakes. Big pipes that were three feet round would empty into them. We caught a lot of shad, but they were very boney. They were not fit to eat, but they were fun to catch. They would swim right up to us, and we would grab them for fun. If we could catch enough to fill a washtub, they would give us a whole five bucks.

Other types of fish we caught were good to cook and eat, like bluegill. Of course, we couldn’t afford bait, but we did not need to. Waddy and I found out that an effective bait, especially for bluegill, was water crickets. We would rake the shallows near underwater grass or stones, and these water crickets would pop up. They were only about a third of an inch long, but they could get around pretty good underwater, and so they made great bait. We would hook one and toss it out over the water on a simple line, and them bluegill would love to take a lunge at them. Even better, we could catch a whole bunch of them and take them over to the bait shop, where we could get a penny a piece for them. So if you had a hundred, that was a dollar; pretty good money for those days.

Many of our fishing spots were way out in secluded areas. There was a rumor that the gangster Pretty Boy Floyd had a hideout there. Every once in a while, we might see some stranger back there, walking by at a distance, so I probably saw him once or twice.

Now Waddy would do just about anything for a laugh, and he loved to see others in some sort of distress. Sometimes, we would go out to a lake and gig for snapping turtles. We could get up to five bucks for one. Normally, we’d take out our old johnboat. One guy would stand in front and pole. The other one would do the gigging using a nice two-prong branch with the ends sharpened. Waddy liked to be in front. So he’d pole, and I’d gig, which worked out well, because I was better at that. When he spotted a turtle’s head moving along the water making a trail through that green crap on the surface, he would steer the boat after it, and I would spear the thing.

One day, we were out gigging by Nesmuth Lake. I was at the stern this time, doing the poling. Waddy was at the front with the wooden gig. He spotted a turtle head gliding along, and told me to steer the boat over to the spot. When we got close, instead of gigging the turtle, Waddy leaned over, reached down, grabbed it, and threw up it into the boat, next to me.

He grinned and said calmly, “Here, tie this sonuvabitch up.”

My eyes must have got big around as the turtle flopped there, and I said, “Damn!” I mean, this was one big-assed turtle. My first thought was to jump out of the boat. I grabbed a rope and when he opened his mouth to snap at me, I shoved the rope into his mouth and wrapped it around his head. Boy, I had some choice words for Waddy while he laughed his head off.

In junior high school, one of the most popular pastimes was marbles. Every kid had a sack of marbles, one of them little pull-string sacks. At recess, all the kids would run outside. The marble players would get together, and the rest of the kids would gather around to watch. Then we would start shooting marbles. We had all kinds of games and once in a while, a contest. I considered myself a great marble player, and in the sixth grade, I fancied myself the marble champ in the school. That was my highlight of sixth grade.

I tried to participate in school sports, and one season I tried out for football, but as it turned out, I could not stay on the team, because you needed three bucks to pay for a doctor’s examination.

I went to Pop, “I need three dollars to get that exam.”

My old man hit the roof. He refused to come up with the money. We were destitute. You just couldn’t get that kind of money out of poor folks back then, especially from tightwads like my dad. Hell, in those days, it only cost a nickel to get into the movie theater, and he didn’t even want to give me that. You know, they had them weekly 15-minute serials back then, and I just loved them. But I never got a nickel for Saturdays, and no money, no admittance. So of course, I’d sneak in. When the guy wasn’t looking, I’d slip around him and get in that way.

Most of the time though, I spent the hours alone, wandering around, exploring.

Once I had the opportunity to work in the circus when it came to Akron. I was about 12 or 13 at the time. Waddy and I walked over to where they were setting up the tents and hung out with other local workers that they had hired for odd jobs. Actually, nearly all of them were hobos that lived in the “hobo jungles” around the swamp next to the railroad tracks near Waddy’s house. We would often walk by their campouts and sometimes stop and listen to them talk.

We were enthralled with everything about the circus, and so like the hobos, we tried to get odd jobs, sometimes just working for free to get in and see the acts. This one year, we were “hired” to haul water for the elephants. The circus supervisor figured that we should do our jobs just for the privilege of being there, so we were not paid. Hell, they didn’t even give us free admission to see the shows.

Naturally, that was not going to stop us, so that night we tried to sneak in. We knew the layout of the area where the elephants were kept because we had worked there, so that was the spot where we would try to get in. The only ones that tried to stop us from getting in were, surprisingly, the damn elephants.

Now growing up in the outdoors, I had seen plenty of dung in my life. But I had never seen elephant droppings before, and these elephants were full of them. The dung balls were huge, and not very round, but oblong. They looked like heavy, brown loaves of bread, or flattened volleyballs, with the ends sort of squared off. Well, as we tried to sneak in, a couple of them saw us. They started grabbing these dung balls with their trunks and threw them at us. I didn’t know they could even do that.

Have you ever been hit in the chest with elephant crap? It’s bad enough that they smell and smear your shirt, but the damn things will knock you over. Some gratitude for getting those monstrosities fresh water.

Still, I loved working there for the circus, and after watching a couple of the shows, I seriously thought about going off with them. But in the end, I decided to stay where I was. I sometimes wonder what my life would have been like if I had joined that circus.

I have to admit that back in the thirties, my brother and I were two ornery little rascals. You could say the same for the Getz brothers. I wouldn’t say we were out and out delinquents, and we never did anything to try to hurt anyone. We didn’t go out to roll anyone or beat anybody up. We were just having fun. Still, we often got into trouble just for the spirit of the adventure.

Take Halloween, for instance. No one went trick or treating—I mean, it was the Depression. People didn’t have anything to give out back then, and it was a sure thing that no one could afford to give out candy. So we’d take some cow crap, tiptoe up someone’s steps, and smear it all over the doorknob. Then we would knock on the door and run like hell. Whoever was home would open the door, come out and see no one. Hopefully, they would grab the outside knob to go in again, and thus get the crap all over their hands. Then we would ha-ha-ha and go off to try it again.

Then there was the time we faked a corpse along the side of the road. We just wanted to shock some folks for the hell of it. Waddy, Alex and I put together this dummy made out of straw, some leaves, and a few tree branches. We dressed it with some stinky old clothes that we had found in the dump along with a couple of old shoes, and tied a thin piece of rope to one of the legs. We smudged the rope with soot so that it would not stand out in the dark.

One spot we picked was next to a wooded area along this gravel road. The location was perfect. It was along a relatively clear stretch next to these swamps, with a cemetery on each side of the road. We got Waddy to act as lookout, so he would climb a tree and sit up there. We then would put the dummy alongside the road to make it look like a dead body, and string the rope down the embankment and into the woods. When Waddy spotted a car coming, he’d let us know. If a car stopped and the driver got out to check out the dead body, we would yank on the rope and pull the dummy into the woods. The body would seem to disappear, and there would be no corpse out there for the driver to examine. Hopefully, that would scare the crap out of the guy.

That first night, Waddy shimmied up his tree, and Alex and I placed the dummy next to the road, face down, looking like a corpse. We strung the rope into the woods and got behind a tree. Then we waited.

Sure enough, it was not long before Waddy whispered down from above, “Hey, someone’s coming!”

Alex and I crouched down and waited. A car came down the road. It slowed down, and then stopped. As soon as we heard the car door open, we pulled on the rope and our dummy slide down the bank and into the woods with us. We heard couple little muffled sounds come from the guy before he jumped back into his car and took off like a bat out of hell.

We laughed hysterically, and then after a while, set the dummy out again. We did this a few more times, and usually the guy wouldn’t see us. No, they would look for the body, not see it, and then freak out, jump back in the car, and take off in a swirl of dust.

One time though, the driver caught on and took off after us. But we were masters at getting away from folks, and once we fled into the swamp, usually no one would want to follow us. And even if they did, they would never be able to catch us. They certainly were in no shape to. No, the swamps were always our refuge.

Years later when I recalled that memory, someone asked me “Hey, what about the guy in the tree? You know, the one that was the lookout? Wasn’t he stuck up there?”

I just laughed and said, “Well, that was his problem. He was supposed to be quiet up there. No one was going to think to look up in the branches, and if they did, they sure as hell weren’t going to spot him up there in the damn dark. So all he had to do was keep his mouth shut and he’d be fine. Besides, I don’t think any of them would be in shape to climb up the tree anyway.”

A week or so later, we decided to try something different. This time, we fixed on using a purse. Times being what they were, we figured someone would stop, hoping that there would be money or jewelry in it. A guy would get out, and we would yank on the rope, and the purse would disappear.

We found an old beat-up purse in the junk yard. Hell, it even had a hole in it, but that didn’t matter to us. We tied it to the rope, found one of our spots along the road, and tried it out one night. Of course, the gag worked, although I have to admit, not every time. Sometimes, the car would keep going. When that happened, we kind of figured the driver did not see the purse in the dark, or saw it and did not know what it was, or just got scared because it looked like a setup and kept going.

We did this a couple times, laughing our heads off afterwards. Unknown to us though, one of these drivers had been on his way to work at the Palmer Match Company,8 which was down the road on the west side, across the street from the Akron Porcelain Company. This guy went into work really mad. He told his co-workers about the missing purse, and said something like, “There’s something fishy going on down there.”

He must have got the whole damn company to come after us, because eight or nine cars pulled up. They kept pulling up and parking, and then these burly guys would get out carrying flashlights and stuff. Crap, there must have been over twenty guys out there trying to find us. Naturally, we got a head start and all took off down the swamps. Not that we needed any, because they were wearing regular work clothes that they probably were not too keen to get all muddy, and we kids were in rags, basically at home in the swamps. The swamp was dark, mucky, and there were a lot of pools of water that they would get soaked in, and bunches of big bushes that we could hide behind or run around. They didn’t catch a darn one of us. But we could hear them up there beating the brush and yelling. They finally gave up and left.

We did other pranks from time to time, but the dead body thing though was our favorite. And from time to time, we would pick a different spot to pull it off. Our favorite place was this one spot next to a factory. We liked it because there was a draw right there, and you could disappear down that draw right into the swamp. Hell, there was no way in the world anyone could catch us. And no one ever did. Good thing I guess, because if any one of us would have ever been caught, he would have gotten his butt beaten.

As luck would have it though, we screwed up again, because the second or third car we did this to was our own, and my dad was driving with a couple of his buddies. They stopped, could not find the purse, and went off towards our house. We were scared now because it was Pop, and because the guys were talking about going to our house and getting a couple of shotguns to come back and to shoot those “rotten sonsabitches that are pulling this crap.” As if that was not bad enough, they had been drinking.

Well, the hell with that! Alex and I took off, splitting up in the swamps. Poor old Waddy in the tree was on his own. I ran through the swamp in the darkness like my life depended on it—which at that point, I reckoned it did. I made it through the backwoods and finally got back home. Dad and his pals were in the living room having a drink of some local stuff they had brewed. They were talking some real trash, getting ready to go out again and look for whoever had pulled that off and shoot them. They were serious, too.

I waited in the living room, and started to worry because there was no sign of Alex. The old man and his buddies finished their drinks and got ready to go out. I could tell that they were getting smashed. I began to freak out. My own father was about to go out and hunt down and shoot my brother, his eldest son. I thought about telling Dad everything, but I figured the shape he was in, daggone, he probably would have shot ME instead.

I was starting to go nuts, wondering what I was going to do, when I heard the back door to the kitchen quietly open. It was Alex, finally home, dirty from head to toe, but safe. Man, I sure breathed a sigh of relief.

Naturally, even though Pop and his cronies were still out there, they didn’t find anything. No people, no purse. Them damn goofs, half lit, were mad as hell and out there talking all kinds of trash, and that they were gonna shoot whoever the hell it was, but we didn’t care. We had made it home safe.

It was just as well though, that the phenomena of the phantom body along the road stopped after that.

We did other things as well during that time, and thank heavens for the swamps so that we could make a quick escape. Sometimes on weekends we would aggravate one or two farmers that lived in the area. We would on occasion go ride their horses. We would take some old rope and make a harness out of it. Then we would toss it over the head of one of his horses in the field and go riding off and play games. Sometimes we would get sticks and just like knights in medieval times, we would go jousting, charging our horses at each other. One time though, we must have miscalculated our steering, and our two charging horses hit head on, and both of them went rolling. It was a wonder we were not killed.

We also used to raise corn and stuff, and we’d sell produce up in the allotment that was bordering our area there. Often though, we supplemented what we sold with produce we would get from other folks.

With time we became bolder in our ventures. There were some fields where blackberries grew, and when they were in season, we would pick them to sell. We got ten cents a quart for blackberries and sixty cents a quart for black raspberries if we could find them.

And corn. My goodness, the corn. There was this one farmer that used to grow this sweet corn. Times being what they were, we thought that we would take advantage of that when the stalks were ripe. Waddy would climb this big maple tree on the other side of the road next to the cornfield, and when it was dark, we would go at it, picking what we wanted. No one could see us. Waddy could see a half mile down the road. And back then, a car wouldn’t come by for a good fifteen minutes or so. It actually got to the point where we started picking corn in broad daylight. We always seemed to get away with it. Then we’d go up to the allotment and sell it. It wasn’t exactly honest, but come on, what else was a poor kid going to do in times like that? I ain’t proud of doing that, but I have to admit, it was kind of funny in a way.

My escapades with stolen corn came up again a few years later when I got ready to go into the service. Although I was 18, I still had to get someone to sign my enlistment papers. My dad would not do it, so I tried to get my grade school principal to sign them. He agreed to, and when I took the papers over to his house, he spread them out on the table, looked at them, and grabbed a pen.

Before he did though, he looked up at me with a squinty eye and said, “Listen though. Don’t think you were fooling me when you were selling me that corn.”

Waddy and I had a couple times stolen some field corn, or what we called “hog corn,” because it was only fit for hogs to eat. But because the kernels were white, we sometimes passed it off to a few people—which included evidently, our principal—as “country gentleman” corn, which was a developed white sweet corn and looked just like what we had stolen.

All I could say was, “Uh, uh …”

He looked square into my face, pointed a boney finger at me, and said, “I knew you were selling me field corn.”

I knew my face was red, and all I could do was look down in shame.

I mumbled, “I’m sorry.” I sure as hell was not going to tell him that besides selling him field corn, I often used to take peaches off of his tree, too. He had a peach tree out in the front yard, and every time I went by there at night, I’d go into his yard and help myself.

Sometimes, just being ornery, we’d go into a farmer’s field where his cows were and milk them. We didn’t carry a pail or anything. One of us would just lie under the cow, and the other one would grab its teat and spurt the warm milk into his mouth. Then we would switch places. Once in a while we got spotted by the farmer, and he’d get mad as hell.

Sometimes he would even get a rifle and take potshots at us. Once I was in his field and heard him bellowing. I looked up and saw him aiming a rifle. I took off for the swamp as I heard a shot. He fired a couple more times, and once I heard the bullet hit a tree nearby. I didn’t know if he was missing me on purpose to scare me or if he was really trying to take me down, but I damn sure was not going to wait around to find out.

The Getz family lived a mile or so down the road on a farm going into the city. Their farm was located in a swamp near one of the Portage lakes. They lived in a cabin that the brothers and their dad, Seymour had built using some old abandoned railroad ties for the four walls. Seymour was a horse trader, and he used the land around the swamp for his horses.

Northward, behind Waddy’s house and next to the swamp were a couple sets of railroad tracks, and on the other side were some open spots where the hobos used to camp out, the “hobo jungles.” For me and Waddy though, this was a place that we loved to visit. He and I enjoyed hanging out with these guys, listening to them for hours, always wanting to hear about their neat adventures (when we were not looking for excitement ourselves). We would sit with them by their makeshift fires, often well into the evening. Sometimes we brought food, like maybe some fish we’d caught that day. We were naturally fascinated with their lifestyles, and so we would stay and watch them cook their meals and be all ears as these vagabonds told these tall tales of things they had seen or done all over the country. We’d get filled with the excitement that two boys could only imagine, as wild, stirring images rushed through our minds.

Sometimes we would even stay all night and have our own little campout with them.

Of course, this gave my old man fits.

He tried to tell me time and time again about how dangerous these guys could be. Still, the idea that hanging out with these vagabonds might not be a safe idea never occurred to us. For one thing, back then, being a drifter did not necessarily mean that you were dumb or a social outcast. Times were rough for everyone. A couple of these guys once upon a time had actually owned some money or had held a high position. But because of the Depression and other things that had happened to them, they for some reason had ended up on the road, bumming from town to town. Surprisingly, there were usually a couple guys in the group that had some education and had been somebody in the past. We figured the dangerous hobos usually stuck to themselves. Besides, back then, we were kids, and did not think that anyone would hurt us.

There was one group that we did fear and stay away from. It was back around 1927. At that time, we lived in a row of four or five flats about two miles from where we finally ended up on Wingate Avenue. We stayed in that flat for six months until, of course, the rent really got overdue. There was a big field behind us, and on the other side was the Goodrich Rubber Company. They had this big storage area with tall piles of old tires. You could always tell when you got close to it, because it seemed like they were always burning some old tires, and you could see the wisps of smoke and smell the burning rubber.

Well, one summer, some gypsies came into that large open area behind our flats. They just moved in and set up some tents. This really upset my mom and dad, because the popular belief back then was that gypsies used to steal kids. So we were told over and over: stay the hell away from those gypsies, or else we’d never be seen again. And let me tell you, it worked, because we never went near them.

When I hit my teens, I started taking an interest in girls. Now Waddy’s dad grew corn in a field about a mile away and he would shuck all the corn on this one acre. Waddy and I played there a lot. Later on, in 1936, when we were in the eighth grade, Waddy got himself a girlfriend named Donna, who was in the seventh grade. He sometimes took her over to this acre to mess around. Even at that age, Donna was already a somewhat loose young thing, and so we sometimes each spent a session with her. One would play lookout, while the other was, shall we say, “getting familiar.” She eventually got the nickname of “Cornshock Donna.”

Her parents owned a home nearby. So sometimes when they were out working, we’d go over to her house and lock the front door. Waddy and I would take turns playing lookout. The only thing was that Waddy was not as diligent about the job as I was, and because of that, we once got into big trouble.

One day my dad got an old Durant car.9 Now he was a wiz at mechanical stuff, and after working on it for a week or so, he was able to fix the engine. In the meantime, he took off all the body parts and the metal work. Then using a rusty old abandoned piece of plow equipment that he had found and pulled out of the ground, he built himself this sizable plow, with a big lever. Then he mounted the plow assembly with wheels onto the back end of the motor frame and somehow hooked up the drive. When he managed to get this monstrosity running, he drove it out to a field and began using it to plow the land. It worked pretty good too, and with it, we used to grow different sorts of vegetables, mostly potatoes. Dad used the plow to first dig up the ground, and then later to harvest the potatoes with the plow pulling them up. Man, at one time we had potatoes all over the place, and kids came in from all over the neighborhood to help us. We’d watch him overturn the ground, and then we would dig into it with our hands. For a while there, we had potatoes coming out of our ears.

As we kids grew older, we became bolder in our adventures. When I was 14, we began to perfect our train-hopping skills. Back then, trains were the major source of transportation for bulk goods, and Akron had miles of main tracks and spurs used for industry, especially along the Belt Line, which was a railroad line that ran between Barberton and Akron along a 15-mile stretch lined with a string of shops and factories. Where we lived, a few of the big companies had their own individual side spurs, where trains would drop off and pick up boxcars and flatcars of supplies. When they did, they moved very slowly, making them easy to hop on. The Akron Porcelain Company would get boxcars full of these dusty 98-lb. bags of some white powder to make the porcelain.10 Waddy and I would sometimes be able to land part-time jobs unloading those bags for cash.

Once in a while, we’d hop on a freight train to help ourselves to products being shipped. One of our targets, especially in the fall and winter, were coal cars. Usually there were a couple in a train, because that was the main fuel that factories used. We would wait at a curve where the train slowed down, and when a coal car came by, we jumped on. We would climb the side ladders to the top and start throwing lumps of coal over onto the ground. When we had tossed enough, we’d climb back down the side ladder, jump off, and then walk back, gathering up the coal lumps to carry them back to our homes for our fireplaces. Coal after all burned much better than wood, and it beat the hell out of sawing and hauling green wood.

Soon Waddy’s younger brother Boysee started coming along with us. Unfortunately, he was not as wise in hopping on, and the second time he tried, he was almost killed. He and I that day had spotted our train, figuring that we would ride it for a mile or two. After all, it beat walking. So, after several cars had gone by, we made our move. Coming out of the bushes on the left side of the tracks, we began running alongside the moving train, picking up speed. Each boxcar or gondola had two iron ladders on each side, one at the front and one at the back. Now the object was to run alongside the train until we got our speed up and came to the ladder that we wanted to jump onto. You’d grab the side rails with your hands and then jump onto the bottom rung footrest. When you did, you had to grip hard, because between the train’s continuing momentum and your sudden stop, there was a tendency for your body to swing around towards the back.

Boysee went first, and I was to follow him and jump onto the next car. Running behind him, I watched as he jogged up next to the train. But he screwed up, making three critical mistakes. First, when he made his move, he was not running as fast as he should have been. As he ran alongside the train, it was moving faster, and the boxcar was slowly passing him. Second, when he finally grabbed for the ladder and jumped on, he managed to grab with only his right hand, and not his left, and as he did so, his feet were not yet firmly planted onto the footrest rung.

The third and most critical mistake was that even though he should have known better, he chose the rear ladder of the boxcar to grab, not the front one. I had learned early on that this was important, because if you hopped onto the front ladder and your body did twirl around because of the train’s momentum, you’d just swing around and smack into the side of the boxcar. All you have to do is hold on to the side rail for dear life. If however, you made your move on the rear ladder and your body swung around, you would twirl around the end of the car into the gap between the cars, and there would be nothing there to stop your swing. So if you whirled around hard enough, you could lose your grip and fall onto the coupling, and probably down between the cars.

And that’s exactly what happened. The train’s momentum swung Boysee into the space between the boxcars, and because he didn’t have a firm hold of the side rail, the swing tore his grasp and he fell backward between the cars. Sliding off the coupling, he slipped down between the moving cars and smacked onto the tracks, stumbling over a couple ties as the second car rolled by above him.

I watched horrified as I ran up and crouched down to try and help him. But there was nothing I could do as the cars rolled by. Boysee got up to his hands and knees, and somehow or another, he quickly scurried over to the other side. Timing the speed of the cars, he lunged between the wheels of the car going over him and as he cleared them, he rolled over the track and down the embankment. He missed getting run over by the car’s right rear wheels by only a couple feet. I breathed a sigh of relief.

1 Oscar A. Hunsicker was on the Akron Juvenile Court Bench from 1930 until 1940.

2 So named because it went through the small town of Manchester, about ten miles south of the lakes, between Canton and Akron.

3 Referred to in earlier years as Nesmith Lake.

4 Weona Club was a chain of over a dozen recreational centers that held social, dancing, and sporting events.

5 The pond in later years was dredged out and Coventry High School was built there.

6 Snydertown, located in the southern part of Barberton, historically for decades was a very poor neighborhood, perhaps the poorest section of Barberton, especially during the Great Depression.

7 These are (usually) domesticated pigeons renowned for their ability to “tumble” as they fly. This is done by rolling over or flipping around backwards in flight.

8 The company, located in Akron, was an Ohio-based corporation, named after Charles Palmer, who also founded the Diamond Match Company.

9 Durant Motors out of Lansing, Michigan, built automobiles from 1920 to 1929. It was later turned into a General Motors Fisher Body center, and subsequently built Buicks and Cadillacs. The factory finally closed in 2005.

10 Powdered kaolin.